Abstract

The collaborative design of technology-enhanced learning is seen as a practical and effective professional development strategy, especially because teachers learn from each other as they share and apply knowledge. But how teacher design team participants draw on and develop their knowledge has not yet been investigated. This qualitative investigation explored the nature and content of teacher conversations while designing technology-enhanced learning for early literacy. To do so, four sub-studies were undertaken, each focusing on different aspects of design talk within six teams of teachers. Findings indicate that non-supported design team engagement is unlikely to yield professional development; basic process support can enable in-depth conversations; subject matter support is used and affects design-decisions; visualization of classroom enactment triggers the use of teachers’ existing integrated technological pedagogical content knowledge; and individual teacher contributions vary in type. Implications for teacher design team members and facilitators are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For teachers, integrating technology in their teaching and in their teaching materials is conceptually challenging and practically demanding (Labbo et al. 2003; Olson 2000). Scholarship on the subject of technology integration increasingly promotes teachers’ active participation in the design of learning material (Koehler and Mishra 2005). Involving teachers as designers has been advocated as a feasible and desirable way of reaching sustained implementation of an innovation in practice (Bakah et al. 2012; Carlgren 1999; Clandinin and Connelly 1992). Active engagement not only increases ownership, but also results in material that is more in line with classroom practice, since teachers know their children and the context better than anyone outside of their classrooms (Ben-Peretz 1990; Borko 2004). A growing number of studies in which teams of teachers act as designers of technology-enhanced learning shows that those teachers do increase technology integration in their classrooms (e.g., Cviko et al. 2013).

Collaboration in teacher design teams (TDTs) has also been argued as a viable and effective strategy for teacher professional development (Voogt et al. 2011). In part, this is because teachers learn from each other as they share and apply knowledge while addressing design challenges. Yet little is understood about how teachers share knowledge, reason and make decisions while designing learning material in TDTs. Based on a review of literature on TDTs, Voogt et al. (2011) concluded that there is a need for studies which closely examine the nature and content of teacher design conversations. The present study addresses that need through four in-depth sub-studies focused on teacher design talk during collaborative design of technology-enhanced learning for early literacy. Detailed reports of the individual sub-studies have been published in scientific journals (Boschman et al. 2016, 2015a, b, 2014). This contribution examines the four sub-studies as a set; it distills key insights that are of relevance to educational professionals working as, or facilitating, teachers as designers of technology-enhanced learning.

Nature and Content of Teacher Design Talk

The nature of design talk refers to the kinds of conversations that occur. Design conversations can be typified in multiple ways. This study examines deliberative interactions; depth of conversations; and the role of subject matter in design conversations. The contents of design talk pertain to the considerations raised as teachers reason through design decisions. Three types of teacher considerations are distinguished in this study. These are existing orientations, practical concerns, and external priorities. Each of these is discussed below.

Nature: What Does Teacher Design Talk Look Like?

Walker (1971) provided groundbreaking analysis of deliberation during curriculum design. His Structural Analysis of Curriculum Deliberation (SACD) framework provides a lens through with the deliberative interactions within design teams can be portrayed. He identified the following types of deliberative interactions. These are brainstorms, issues, reports and explications. Within each type of interaction, he ascertained that individual contributions could be identified as the following: problems, proposals, considerations, or instances. This framework provides starting points for investigating the nature of design talk in TDTs.

Collaborative design has the potential to serve as a context for teacher learning (Handelzalts 2009; Voogt et al. 2011). Collaborative conversations have the potential to support teacher learning whether solving specific problems (Putnam and Borko 2000) or engaging in more general pedagogical reasoning (Horn 2010). But not all conversations are equally deep or enriching. Based on Henry (2012), distinctions in depth of inquiry during collaborative conversations are distinguished as: no collaborative inquiry; shallow inquiry by sharing knowledge and information; deep inquiry, building understanding by analyzing and synthesizing information; and deep inquiry by using understanding to achieve learning by planning. The kinds of conversations that form a context for learning are those in which teachers not only share information (shallow inquiry), but also construct new knowledge by building and applying new understanding (deep inquiry).

Studies have shown that TDTs struggle to apply subject matter expertise during design (Handelzalts 2009). Therefore, support from a subject matter expert is commonly recommended for TDTs (Huizinga et al. 2013). Deketelaere and Kelchtermans (1996) found that such support can take the form of stating opinions, sharing knowledge and beliefs, contrasting, fueling discussions, and clearing up misconceptions. While all of these may be present, no studies have yet examined if or how such contributions elicit teachers’ own subject matter expertise, nor which kinds of expert contributions actually influence design decisions. In this study, subject matter support is operationalized as contributions brought into design conversations from subject matter experts which: ask for clarification, make confirming remarks, state critique, provide suggestions or offer explanations. To better understand the role of subject matter expertise in TDTs, this study examines how teachers’ own content knowledge is manifested in design conversations, as well as the kinds of expert contributions that yield the most influence on design decision-making.

Content: What Considerations Arise Through Design Talk?

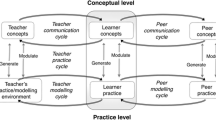

The existing orientations of individual teachers influence the contributions made during design conversations. Building on the work of Lundvall and Johnson (1994), McKenney et al. (2015) describe different kinds of knowledge and beliefs that underpin teacher abilities to ‘engage skillfully’ in the design of technology-enhanced learning (McKenney et al. 2015). Know-what refers to conceptual knowledge and facts, which may exist in isolation, or may consist of integrated technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) as described by Mishra and Koehler (2006). Know-why pertains to teacher’s knowledge and beliefs about principles of learning and teaching. Know-how is a teacher’s skill to produce or facilitate what is needed, such as learning materials, instructional events or classroom management. Several studies have investigated how teachers use their TPACK during instructional decision-making (Doering et al. 2009; Graham 2011; Graham et al. 2012; Manfra and Hammond 2008), but research is needed to understand if and how the existing orientations of individual teachers influence design conversations.

In addition to existing knowledge and beliefs, practical concerns influence teacher decision-making in general (Doyle and Ponder 1977) and also during design. Teachers are aware of the complex ecologies in their classrooms, and take into consideration how feasible, complex or relevant new ideas appear to be as they think about implementing them in practice. Studies have shown that practical concerns dominate TDT discussions (Handelzalts 2009; Kerr 1981). Types of practical concerns raised during collaborative design include: (a) organizational issues (time available, how are students seated, what classroom facilities) (de Kock et al. 2005); (b) relationship between student and activity (how will students react to this, what will students do with it) (Deketelaere and Kelchtermans 1996; George and Lubben 2002; Parke and Coble 1997); and (c) how subject-matter is presented to students in such a way that it becomes feasible in practice (Handelzalts 2009). To date, research has not ascertained if addressing practical concerns is more of a necessary evil or an affordance during design conversations.

While teachers have some freedom in deciding what occurs in their classrooms, external priorities, those of stakeholders other than the teachers themselves, wield powerful influence on teacher decision-making. External priorities may be set by various stakeholders, including state and national governments (e.g., assessment standards); publishers (e.g., textbooks); school boards (e.g., local policies); principals or colleagues (e.g., communities of practice). External priorities are often implicitly embedded in the organizational context in which teachers work. They certainly influence decisions such as which curriculum to adopt or how to prepare for high-stakes testing. What is less understood is if and how teachers consider external priorities in situations like this study, in which a commitment has already been made to engage in the design of a specific form of technology-enhanced learning.

Methods

Context and Participants

The present study endeavored to understand the nature and content of teacher design talk. It took place in the context of Dutch kindergarten education, through design work focused on developing functional literacy. Functional literacy pertains to understanding the communicative purposes of written language. In this study, teachers designed learning materials for use with PictoPal, a technology-enhanced learning environment that enables even non-reading children to ‘write’ and then ‘use’ a variety of products, thereby experiencing their functions, first hand. An example of a PictoPal on-computer writing activity is that children compose and print a list of ingredients for making dinner. They do this using a word processor called Clicker®, that features pre-written, spoken and illustrated words with which children compose their texts. Next, children then engage in an application activity such as ‘buying’ the ingredients on their list (e.g., in the store corner of the classroom) in order to ‘cook’ a dinner (e.g., in the kitchen area of the classroom). PictoPal has shown promising results in children’s attainment of functional literacy (Cviko et al. 2012; McKenney and Voogt 2009).

During a 3 year period, a total of 21 kindergarten teachers were involved in designing the PictoPal learning materials. The teachers were divided over six TDTs. Each TDT consisted of at least two teachers. All of these teachers participated voluntarily after an open call was issued.

Approach, Instrumentation and Data Analysis

Four sub-studies were undertaken to understand design talk as it occurred in a real-life context. The term, sub-study, is used here to indicate separate investigations that are each of independent value, but together help answer a broader research question. Case study methods (Yin 2003) were used for all sub-studies. Sub-studies 1, 3 and 4 used a multiple case study design, whereas sub-study 2 was a single case study.

In each sub-study, teachers attended design workshops in which they created PictoPal materials. Qualitative data were gathered through semi-structured interviews and transcripts of the design workshop conversations. As elaborated in the next section, each sub-study had its own focus. Thus, while the study set as a whole built on the above descriptions of the nature and content of design talk, the specific data analysis techniques varied in each sub-study. These are summarized in Table 1 and described below.

Conversation analysis took place in each case study, but because each sub-study had its own focus, data analysis concentrated on different aspects of teacher design conversations. The first two studies examined the design talk of teams; thereafter, the contributions of individuals were investigated in sub-study 3 (where the design team was comprised of regular teachers and a subject matter expert), and sub-study 4 (examining how individual teachers’ existing orientations influence design conversations). Accordingly, the systematic analysis of the conversations centered on different aspects in each sub-study.

The interviews were conducted in sub-studies 1 and 4; they investigated teachers’ existing orientations with regard to technology, pedagogy, early literacy and design (see Table 1). All interviews were transcribed and written data were descriptively coded. In sub-study 1, the coding examined relationships to existing orientations (pedagogy, technology, early literacy or design). Then, categories of inductive codes were made through axial coding which resulted in sub-codes within pedagogy, ICT, early literacy or design. These category codes were refined through constant comparison (Glaser and Strauss 1999). In sub-study 4, coding focused on categories of design knowledge: know-why, know-what, and know-how. Here too, the codes were refined through constant comparison.

The TDT conversations were recorded on video and later transcribed. The written transcripts were analyzed using techniques derived from the work of Sacks et al. (1974), which recognizes that ordinary conversation is organized by the following rules: (a) Conversation is interaction, meaning that speakers turn their attention to another speaker; (b) Speakers take turns and conversation, while the flow of the conversation may seem unstructured, conversation itself is orderly; (c) Finishing each others’ turn and repeating what another speaker said, signals agreement; and (d) Understanding emerges as speakers talk about the same topics.

Findings

Sub-Study 1

The goal of sub-study 1 was to portray teachers’ intuitive approaches to designing technology-enhanced learning for early literacy. This sub-study investigated deliberative interactions and the kinds of argumentation that underpins decisions within three design teams. Two of the design teams were comprised of regular kindergarten teachers; one design team was comprised of kindergarten teachers with a-typically high level of early literacy expertise. The teams were given an explanation of PictoPal’s rationale and demonstration of previously designed material, but the design process was otherwise unstructured.

The findings from the interviews showed that pedagogical beliefs, about teaching and learning in kindergarten, are a dominant lens through which technology was viewed. Teachers indicated that they direct their attention to socio-emotional development of children first, before considering the kinds of learning that have to take place. The interviews suggested that teachers draw most on their own personal experiences to feed the design of (technology-enhanced) learning materials.

The analysis of the design talk indicated that the dominant mode is that of brainstorming, occasionally interrupted by brief moments in which issues are discussed. When mentioned, issues are mainly related to practical concerns, and teachers work to quickly find solutions. Argumentation from existing orientations and external priorities were scarcely reflected in this data set. However, when comparing the regular kindergarten teacher design talk to that of teachers with extensive early literacy expertise, the latter group did infuse the conversation more often with their existing orientations (knowledge and beliefs). It was concluded in this study that teachers’ natural inclinations during design are solution-driven, having rarely progressed beyond brainstorming. Furthermore, practical concerns feature prominently in discussions, and participants with higher levels of subject matter expertise draw more explicitly on this knowledge than regular teachers.

Sub-Study 2

Sub-study 2 explored collaborative design talk as a context for teacher learning. Specifically, it focused on how teachers draw on their existing orientations (TPACK) and depth of inquiry in design conversations. One team of six highly experienced teachers was involved, ranging from 24 to 40 years of teaching kindergarten. This group was given minimal procedural support by a researcher/facilitator, who organized three design workshops, set target outcomes of each one, and responded to any questions about PictoPal.

Findings revealed that the kinds of knowledge teachers introduced most to the conversations were PCK (pedagogical content knowledge) and TPCK (technological pedagogical content knowledge). General pedagogy was not discussed in isolation, but intertwined with the two other knowledge domains in the forms of: technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK); pedagogical content knowledge (PCK); or technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). PCK and TPCK were closely linked to teachers’ practical concerns.

The findings of this study showed that teachers reached deeper levels of inquiry as the workshops progressed (as evidenced by analyzing and planning), but that most of the design talk reflected lower levels of inquiry (sharing information). A pattern emerged in which teachers first share information by proposing what the learning activity could look like. This continued, uncontested, until another teacher would cast doubt or make an evaluative comment. Considerations for decision-making were mainly given by sharing information. Moments of deeper levels of inquiry were also moments in which important decisions are made. Along the way, teachers established a rationale, which then guided further design.

Sub-Study 3

Sub-study 3 investigated the role of early literacy content knowledge (CK) in TDT conversations. One team of four and one team of two teachers each designed PictoPal learning material. An early literacy expert, who, after many years of teaching herself, had gained extensive experience as an in-service educator, supported each team. This study analyzed the manifestation of teachers’ existing orientations toward early literacy in their design talk (CK, TCK, PCK and TPCK), argumentation in decision-making, and the kinds of expert contributions that yielded the most influence on design decision-making.

The findings of this study revealed that CK was utilized when teachers discussed the current goals and objectives of early literacy, set within specific themes in their classrooms. PCK was explicated when relating to current and future classroom learning practices, or activities that would occur with written material. TCK was used when teachers discussed the on-screen layout of written materials that children would conduct. TPCK emerged as teachers discussed how children would produce the written material and how they would use the material in play-related application activities.

The analysis on teacher reasoning behind decisions showed that existing orientations (knowledge and beliefs) related mostly to CK and PCK. Reasoning through practical concerns appeared to trigger teacher use of integrated technological knowledge (TCK and TPCK). Content knowledge seems to have served as an internal compass for designing the material and talking about practical concerns.

Contributions given by the early literacy expert were categorized as either: clarification, confirmation, critique, suggestions, or explanations. Analysis of decision-making processes showed that recommendations and explanations wielded the most influence on TDT design decisions. Recommendations made pertained to concrete learning activities; whereas the explanations provided related to CK, elaborating specific concepts or clarifying misconceptions pertaining to early literacy.

Sub-Study 4

Sub-study 4 was undertaken to understand how individual teachers’ design knowledge was utilized during design talk. To understand the kinds of contributions individual teachers bring to collaborative design, the analysis identified individual teacher explication of design knowledge; it also tracked resulting influences on the designed product. The transcript from the team of four teachers described in sub-study 3 reanalyzed using a different coding scheme, related to design knowledge (know-what, know-why, and know-how).

The interviews revealed that teachers possess and articulate substantial know-why, but the conversation analysis showed that it is expressed much less frequently during design. Rather, know-how was expressed most during design talk. The interview findings suggest that know-why underpins the know-how. Know-what was expressed the least by teachers.

This study also found differences between teachers. Of the four teachers, two teachers were inclined mostly to express know-how. These two teachers also made more contributions to the design than the other two teachers did. Of the other teachers, one teacher proportionally expressed more know-what and one teacher more know-why. Analysis of the team outcome showed that not all contributions were visible in the final designed product, but that key ideas from each individual teacher were. This study highlights the variety in kinds of contributions made by individuals in teacher design teams.

Discussion

This study sought to understand the nature and content of teacher design talk. In so doing, four sub-studies were conducted, each with its own focus. The findings from sub-study 1 indicate that teachers draw most on their own experiences and convictions when designing. Further, teachers’ intuitive approaches to design rarely move beyond brainstorming. This suggests that benefits of TDT engagement (e.g., teacher learning) are likely to be limited when teachers rely on their intuitive approaches alone.

Sub-study 2 showed that use of PCK and TPCK were closely linked to resolving teachers’ practical concerns. Sub-study 2 also showed that, with limited process support, deep inquiry is rare but present. Thus, it can be cautiously concluded that minimally structured design conversations have the potential to serve as a context for teacher learning.

Sub-study 3 found that content knowledge played a significant role during design. Additionally, it found that integrated content knowledge (TPCK) was triggered when TDTs collaboratively reasoned through practical ramifications of design options. This study also revealed that subject matter expertise, as offered by an external participant, was most used for decision-making when given in the forms of explanations and recommendations.

Sub-study 4 examined the kinds of design knowledge brought by different individuals in a team. It ascertained that not only are the specific contributions different, but that the kinds of contributions individual teachers bring vary. Specifically, two brought more know-how, one more know-what, and one more know-why. The different contributions influenced the discussions, as well as the resulting designed product. Table 2 summarizes key findings and provides illustrative quotations for each.

Limitations

Interpreting the findings from the four sub-studies should not be undertaken without understanding potential limitations of the research approach. Three potential limitations bear mention: First, in assessing the generalizability of these results, it is necessary to note the small sample size. While the approach chosen was helpful for this explorative study, additional research is needed to ascertain if the patterns observed here can be expected among a broader range of contexts, and teachers, and if the findings apply to other subject areas. Second, this study was limited to the design of one kind of learning material, PictoPal. For investigating the generalizability of the findings in relation to early literacy, similar studies involving the design of different digital learning materials and activities for early literacy are needed. Third, this study examines pre-implementation design only. Because implementation experiences affect teacher learning by design (Voogt et al. 2011), future research should explore the nature and content of conversations during initial design, as well as during post-implementation re-design conversations.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of the four sub-studies, several considerations for practice can be distilled. Phrased as key considerations for the TDT member or facilitator, these are summarized (in relation to each sub-study) as follows:

-

1.

If teacher professional development is a main goal for establishing TDTs, this approach is not likely to succeed if it relies (heavily) on teacher intuitive approaches to design.

-

2.

Basic process support (planning) can enable in-depth conversations in TDTs, but these are likely to be limited.

-

3.

To trigger sharing and use of TPCK, TDTs should be stimulated to visualize actual enactment. Also, in addition to basic planning support, subject matter support is useful to TDTs and does affect design decision-making.

-

4.

To engage all TDT participants and to maximize use of their diverse knowledge to the enrichment of the final designed product, TDT facilitators should not necessarily work toward consensus immediately (a natural inclination for most designing teachers), but explicitly attempt to draw out the varied perspectives and knowledge within the group.

Closing Considerations

The research described here offers one approach to understanding teacher design talk. While studies on teachers as designers of technology-enhanced learning are growing (e.g., as evidenced by a recent special issue of Instructional Science on the topic), the current knowledge based is still limited. With its microanalysis of TDT conversations, the present research makes a unique contribution. However, further inquiry is warranted to fully understand and ultimately support teachers in the challenging and exciting task of designing technology-enhanced learning.

References

Boschman, F., McKenney, S., Pieters, J. & Voogt, J. (2016). Exploring the role of content knowledge in teacher design conversations. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. doi:10.1111/jcal.12124.

Boschman, F., McKenney, S., Pieters, J. & Voogt, J. (2015a). Teacher design knowledge and beliefs for technology enhanced learning materials in early literacy: Four portraits. eLearning Papers, 44. http://www.openeducationeuropa.eu/en/article/Teacher-design-knowledge-and-beliefs-for-technology-enhanced-learning-materials-in-early-literacy%3A-Four-portraits.

Boschman, F., McKenney, S., & Voogt, J. (2015b). Exploring teachers’ use of TPACK in design talk: The collaborative design of technology-rich early literacy activities. Computers & Education, 82, 250–262.

Boschman, F., McKenney, S. & Voogt, J. (2014). Understanding decision making in teachers’ curriculum design approaches. Educational Technology Research and Development, 62, 393–416.

Bakah, M. A. B., Voogt, J. M., & Pieters, J. M. (2012). Advancing perspectives of sustainability and large-scale implementation of design teams in Ghana’s polytechnics: issues and opportunities. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(6), 787–796. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.11.002.

Ben-Peretz, M. (1990). The teacher-curriculum encounter: Freeing teachers from the tyranny of texts. State University of New York Press.

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: mapping the terrain. Educational Researcher, 33(8), 3–15. doi:10.3102/0013189x033008003.

Carlgren, I. (1999). Professionalism and teachers as designers. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(1), 43–56.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (1992). Teacher as curriculum maker. In P. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp. 363–395). New-York: Macmillan.

Cviko, A., McKenney, S., & Voogt, J. (2012). Teachers enacting a technology-rich curriculum for emergent literacy. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(1), 31–54.

Cviko, A., McKenney, S., & Voogt, J. (2013). The teacher as re-designer of technology integrated activities for an early literacy curriculum. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 48(4), 447–468. doi:10.2190/EC.48.4.c.

de Kock, A., Sleegers, P., & Voeten, M. J. M. (2005). New learning and choices of secondary school teachers when arranging learning environments. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(7), 799–816. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.012.

Deketelaere, A., & Kelchtermans, G. (1996). Collaborative curriculum development: an encounter of different professional knowledge systems. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 2(1), 16.

Doering, A., Veletsianos, G., Scharber, C., & Miller, C. (2009). Using the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge framework to design online learning environments and professional development. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 41(3), 319–346.

Doyle, W., & Ponder, G. A. (1977). The practicality ethic in teacher decision-making. Interchange, 8(3), 1–12. doi:10.1007/bf01189290.

George, J. M., & Lubben, F. (2002). Facilitating teachers’ professional growth through their involvement in creating context-based materials in science. International Journal of Educational Development, 22(6), 659–672.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1999). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research: Aldine Transaction.

Graham, C. R. (2011). Theoretical considerations for understanding technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK). Computers & Education, 57(3), 1953–1960. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.04.010.

Graham, C. R., Borup, J., & Smith, N. B. (2012). Using TPACK as a framework to understand teacher candidates’ technology integration decisions. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(6), 530–546. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00472.x.

Handelzalts, A. (2009). Collaborative curriculum development in teacher design teams. (PhD Doctoral), Universiteit Twente, Enschede.

Henry, S. (2012). Instructional conversations: A qualitative exploration of differences in elementary teachers’ team discussions. (ED Doctoral Dissertation), Harvard University.

Horn, I. (2010). Teaching replays, teaching rehearsals, and re-visions of practice: learning from colleagues in a mathematics teacher community. Teachers College Record, 112(1), 225–259.

Huizinga, T., Handelzalts, A., Nieveen, N., & Voogt, J. M. (2013). Teacher involvement in curriculum design: Need for support to enhance teachers’ design expertise. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(1), 33–57. doi:10.1080/00220272.2013.834077.

Kerr, S. T. (1981). How teachers design their materials: implications for instructional design. Instructional Science, 10(4), 363–378.

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2005). What happens when teachers design educational technology? the development of technological pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 32(2), 131–152.

Labbo, L. D., Leu, D. J., Jr., Kinzer, C., Teale, W. H., Cammack, D., Kara-Soteriou, J., et al. (2003). Teacher wisdom stories: Cautions and recommendations for using computer-related technologies for literacy instruction. Reading Teacher, 57(3), 300–304.

Lundwall, B., & Johnson, B. (1994). The learning economy. Journal of Industry Studies, 1(2), 23–42.

Manfra, M. M., & Hammond, T. C. (2008). Teachers’ instructional choices with student-created digital documentaries: case studies. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 41(2), 223–245.

McKenney, S., & Voogt, J. (2009). Designing technology for emergent literacy: the PictoPal initiative. Computers & Education, 52, 719–729.

McKenney, S., Kali, Y., Markauskaite, L., & Voogt, J. (2015). Teacher design knowledge for technology enhanced learning: an ecological framework for investigating assets and needs. Instructional Science, 43(2), 181–202. doi:10.1007/s11251-014-9337-2.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Olson, J. (2000). OP-ED trojan horse or teacher’s pet? computers and the culture of the school. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 32(1), 1–8.

Parke, H. M., & Coble, C. R. (1997). Teachers designing curriculum as professional development: a model for transformational science teaching. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(8), 773–789.

Putnam, R., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(1), 4–15. doi:10.3102/0013189x029001004.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735. doi:10.2307/412243.

Voogt, J., Westbroek, H., Handelzalts, A., Walraven, A., McKenney, S., Pieters, J., et al. (2011). Teacher learning in collaborative curriculum design. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(8), 1235–1244. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.07.003.

Walker, D. F. (1971). A study of deliberation in three curriculum projects. Curriculum Theory Network (7), 118–134.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. SAGE Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McKenney, S., Boschman, F., Pieters, J. et al. Collaborative Design of Technology-Enhanced Learning: What can We Learn from Teacher Talk?. TechTrends 60, 385–391 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0078-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0078-8