Abstract

This article presents a comparative study of the semantics of conversion between verbs and nouns in two languages with different morphological structures – English and Czech. To make the cross-linguistic comparison of semantic relations possible, a cognitive approach is used to provide conceptual semantic categories applicable within both languages. The semantic categories, based on event schemata introduced by Radden and Dirven (2007) primarily for syntactic description, are applied to data samples of verb–noun conversion pairs in both languages, using a dictionary-based approach. We analyse a corpus sample of 300 conversion pairs of verbs and nouns in each language (e.g., run.v – run.n, pepper.n – pepper.v; běhat ‘run.v’– běh ‘run.n’, pepř ‘pepper.n’ – pepřit ‘pepper.v’) annotated for the semantic relation between the verb and the noun. We analyse which relations appear in the two languages and how often, looking for sizeable differences to answer the question of whether the morphological characteristics of a language influence the semantics of conversion. The analysis of the annotated samples documents that the languages most often employ conversion for the same concepts (namely, instance of action/process and result) and that the range of semantic categories in English and Czech is generally the same, suggesting that the differences in the morphology of the two languages do not affect the range of possible meanings that conversion is employed for. The data also show a difference in the number of types of combinations of multiple semantic relations between the verb and the noun in a single conversion pair, which was found to be larger in English than in Czech, and also in the frequency with which certain individual semantic relations occur, and these differences seem to be at least partially related to the morphological characteristics of Czech and English.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Conversion is a well-studied phenomenon in English, typically understood as “the process by which lexical items change category without any concomitant change in form” (Lieber, 2005: 418). The concept has also been discussed in the cross-lingual perspective to see how it can be approached in languages with different morphological characteristics (Valera, 2015). In languages where word class is marked by overt inflectional material, formal identity between words from different word classes is rare. In this context, conversion is defined as word-formation without the use of derivational material, based on the fact that although there may be changes in inflectional markers, “a new meaning is added which is not supported by any derivational morpheme” (Štekauer et al., 2012: 213). English has also been the main focus of descriptions of the types of semantic change that occurs in conversion (Marchand, 1969; Adams, 1973; Clark & Clark, 1979; Cetnarowska, 1993; Plag, 1999; Martsa, 2013). However, there is only limited research on whether the range of semantic types found for English is also applicable to other languages and whether the type of semantic change is influenced by a language’s morphological characteristics.

This article presents a comparative study of the semantic types of conversion between verbs and nouns in English and Czech as a contribution to investigating the interaction between the range of semantic categories expressed by conversion and the language’s morphological characteristics. Our methodology is based on cognitive approaches to conversion as metonymy (Kövecses & Radden, 1998: 54–61; Dirven, 1999; Buljan, 2004; Schönfeld, 2005; Martsa, 2013) and approaches that apply semantic classification of conversion on language data (Gottfurcht, 2008; Valera, 2020; Mititelu et al., 2023). Conceptual semantic categories applicable across both languages are applied to a random sample of 300 conversion pairs of verbs and nouns extracted from corpora in each language, and the differences between the types of categories assigned in each language and their frequency are analysed. Our approach abstracts from the direction of conversion, the determination of which is a notorious issue in conversion research (Marchand, 1964; Plank, 2010; Bram, 2011; Tribout, 2020) and becomes even more pronounced in the cross-lingual perspective.

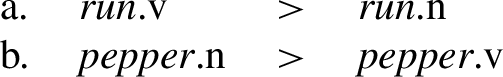

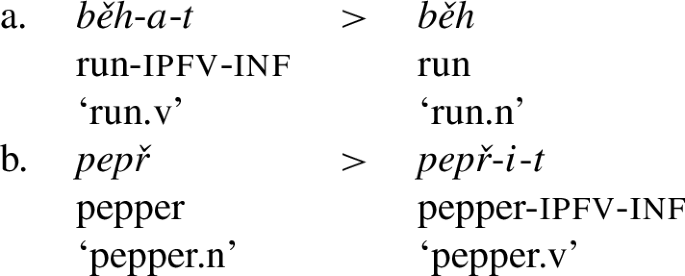

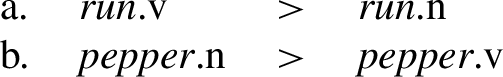

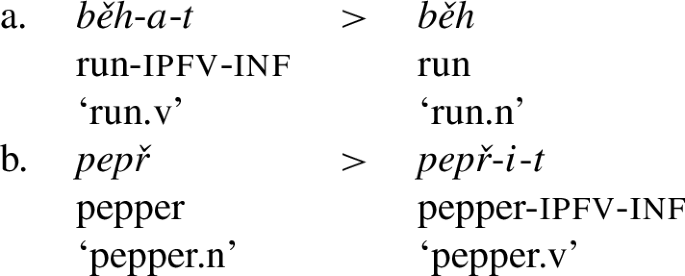

We focus on English and Czech as representatives of languages with different morphological characteristic affecting the formal aspects of conversion between verbs and nouns. English is a language with predominantly analytic morphological features in which the citation forms of nouns and verbs do not include any overt inflectional markers, and it is therefore possible for a noun and a verb to have completely identical forms, as exemplified in (1). Czech is a language with rich inflectional morphology and verbs have obligatory overt inflectional markers even in their citation forms – it is therefore not possible for a verb and a noun to have identical forms, as exemplified in (2); cf. the thematic suffix (conveying the imperfective grammatical aspect) and the infinitival ending which are dropped when converting the verb běhat ‘run.v’ to the noun běh ‘run.n’ in (2a), and the addition of these inflectional markers to the noun in the reverse process of forming the verb pepřit ‘pepper.v’ in (2b). However, in both languages, the pairs do not differ in word-formation affixes – the morphological structure of nouns and verbs that are the result of conversion is the same as the structure of a primary unmotivated noun or verb (see Sect. 2.1 for more details).

-

(1)

-

(2)

The fact that in English, words can be used as nouns or verbs with such ease because there is no change in form required (e.g., Bauer, 1983: 226–227) is often spoken about in connection with the wide semantic range covered by conversion. Many authors have remarked on the large variety of meanings that converted words express compared to words formed by the addition of overt derivational material (Plag, 1999: 220–221, Lieber, 2005: 422). In the Czech context, the verbal thematic suffix and the nominal inflectional ending can be assumed to perform the role of the derivational affix and therefore have a similar type of semantic effect. For example, in the Czech academic grammar (Štícha et al., 2018), verbs formed using conversion are first classified based on the thematic suffix (similarly to the way derived words are classified based on the derivational affix), and only then described in terms of meaning categories. In contrast, our analysis documents that the formal specifics of Czech conversion do not make the process significantly different from English conversion in terms of the semantic change involved and the range of meanings that it can express.

Our analysis shows that the same set of conceptual categories appears in Czech and English in a comparable sample of conversion pairs, with only marginal categories missing in one language and present in the other. At the same time, no residual category was needed in either language – all pairs could be classified into one of the previously defined semantic categories. The same two categories (instance of action/process and result) occur the most frequently in both languages. Differences were found in the frequency of some other categories and also in the number of combinations of multiple categories in a single conversion pair, which was larger in English. The finding that differences between the Czech and English sample do not affect the range of categories expressed in conversion, but rather, in some cases, how frequently the categories are expressed, has implications for the nature of the influence of a language’s morphological type on the semantic types of conversion.

The article is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we review the literature on conversion in English and Czech (Sect. 2.1) and on the semantic classification of conversion (Sect. 2.2) and outline the relevance of previous cognitive approaches to conversion for the semantic comparison carried out in this article (Sect. 2.3). In Sect. 3, we describe the data compilation procedure and introduce the method used for semantic annotation. The method is novel in that cognitive categories that are primarily designed for describing the syntactic-semantic structure of sentences are applied to the cross-linguistic comparison of conversion. To the best of our knowledge, such comparative analysis has not been carried out so far. The results of the analysis, presented in Sect. 4, show that the English and Czech samples document a similar range of semantic categories and the two most frequent categories in both languages are the same, but reveal some differences in the frequency of some other categories as well as in the types of their combinations in a single conversion pair. The implications of the findings for the nature of the interaction between a language’s morphological characteristics and the semantics of conversion are discussed in Sect. 5. Concluding remarks close the paper in Sect. 6.

2 Background

2.1 Conversion as an independent word-formation process in English and Czech

Conversion has received much more attention in English than in other languages, partly because the concept draws on the properties of English and it is less clear whether and how to handle it in languages with different morphological characteristics. Conversion is defined in the classical references as the transfer of a word into a new word class without a change of its form (Adams, 1973; Bauer, 1983; Štekauer, 1996; Plag, 2003; Bauer et al., 2013, among others). The nature of this transfer has been discussed under many different theoretical approaches. Due to the identity of the words’ citation forms in English, it may be questioned whether a new word is being created, or whether conversion simply involves one word of unspecified word class being used in different functions. Such a view is taken by Farrell (2001) who describes conversion as category underspecification. In Distributed Morphology, conversion is treated as a syntactic phenomenon involving noun incorporation (Hale & Keyser, 2002; Harley, 2005). Approaches which do see conversion as a type of word-formation differ in how the specifics of the word-formation process are described – conversion can be seen as a type of coinage (Lieber’s 2004 relisting), zero-derivation (based on the analogy between conversion and derivation using overt affixes, e.g., Marchand, 1969; Kastovsky, 2005) or as a recategorization without the addition of derivational material (e.g., Štekauer, 1996).

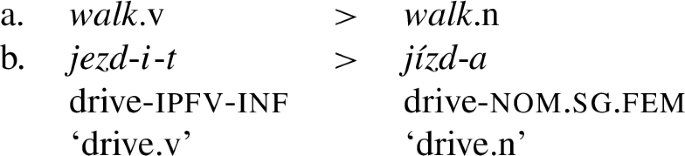

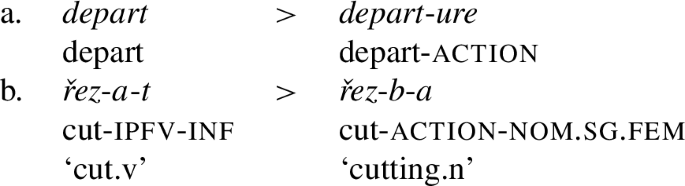

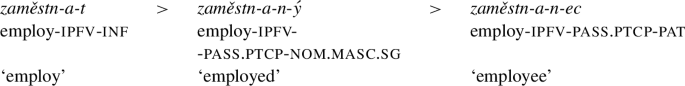

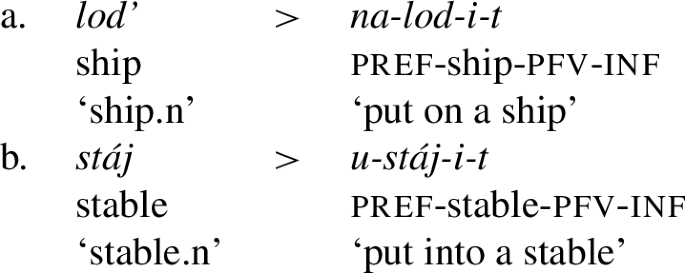

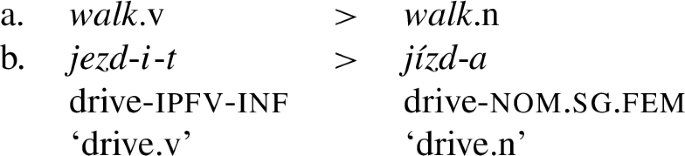

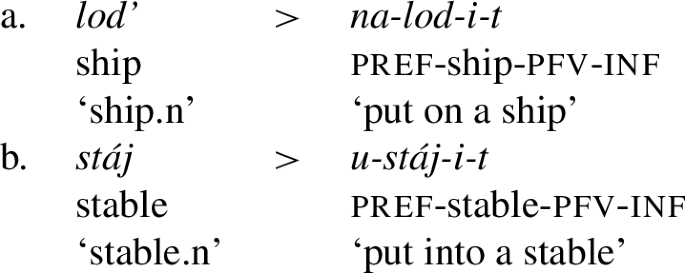

The English-based definition of conversion which uses the criteria of word-class change and formal identity has been modified when examining comparable word-formation in other languages (Valera, 2015). If we take languages with rich inflectional morphology into consideration when defining conversion, formal identity is rare (in Czech, it can be found e.g. in nouns converted from adjectives, such as cestující.adj ‘travelling.adj’ – cestující.n ‘traveller, passenger’, but not in conversion between nouns and verbs) and inflectional affixes usually change during the word-class transfer. Therefore, in approaches that consider languages other than English, the lack of added/removed derivational material can be taken as the defining characteristic of conversion (cf. Manova, 2011; Štekauer et al., 2012), as opposed to derivation, where a new word is created by adding a derivational affix – compare examples of forming action nouns without derivational affixes in English and Czech (3a, b, respectively) vs. with a derivational affix in English and Czech (4a, b, respectively). In 3b, the thematic suffix expressing grammatical aspect is dropped and the inflectional ending expressing nominal grammatical categories is added when creating the noun from the verb. In 4b, the process of creating the noun includes the same change in grammatical markers, but also the addition of a derivational affix expressing the meaning of action. Although the terminology is not unified in the Czech linguistic tradition and the understanding of the nature of the process differs between authors, the term konverze has been used to denote the verb–noun pairs under discussion in Czech grammars and works on word-formation (Dokulil, 1962; Daneš et al., 1967; Dokulil et al., 1986; Bednaříková, 2009; Štícha et al., 2018). Dokulil (1962) defines conversion as a type of word-formation process in which a new word is created merely by changing its inflectional paradigm, which may manifest itself in a change in overt inflectional affixes even in the citation forms of the words.

-

(3)

-

(4)

Under standard assumptions, if conversion is considered a type of word-formation, it then follows that it is also a directional process, with a motivating word and a resulting motivated word. Due to the absence of derivational material, determining the direction of conversion is often difficult. Several criteria have been proposed, both diachronic (in particular, date of attestation) and synchronic (e.g., semantic dependence, restriction of usage, frequency, semantic range, semantic pattern, phonetic shape, morphological type, stress; cf. Marchand, 1964). However, determining the direction of conversion remains a difficult task because applying different criteria may lead to conflicting results (Bram, 2011). In addition, Plank (2010) shows that different directions may be established for different senses of a single conversion pair. Conversion may also be considered inherently bi-directional (Bergenholtz & Mugdan, 1979; Becker, 1993; Tribout, 2020) or non-directional due to category underspecification (Farrell, 2001).

2.2 Semantic classification of conversion between nouns and verbs

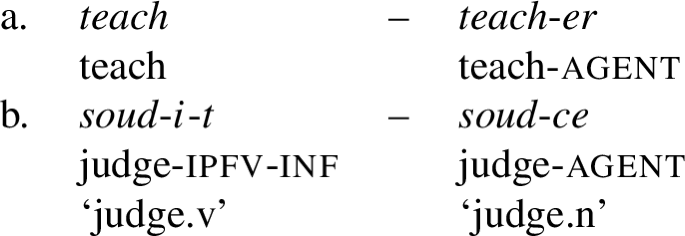

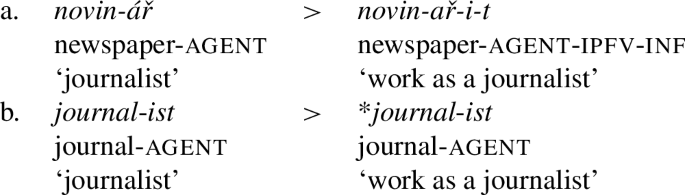

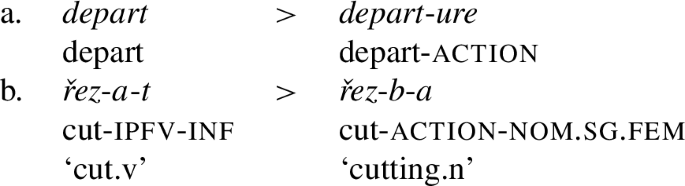

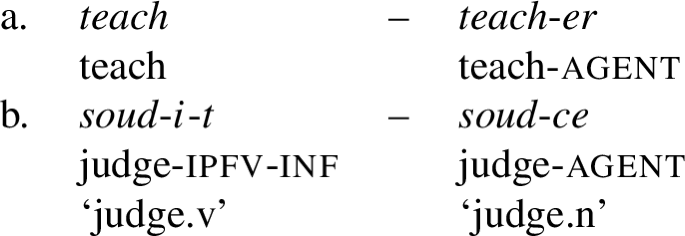

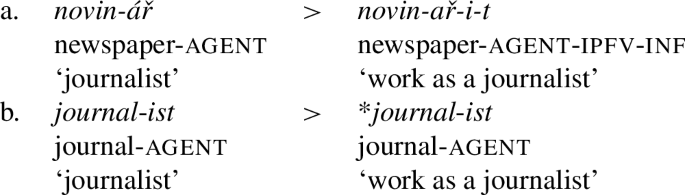

The absence of derivational material makes the description of the semantics of conversion substantially different from the description of derivation, where the meaning change between the input and output words can be ascribed to the affix attached through this process (cf. Bagasheva, 2017; Körtvélyessy et al., 2020). Cf. the derivation of action nouns in English and Czech in examples (3), (4) or the derivation of agent nouns in (5a) and (5b), where the affix adds the meaning of agent to the actional meaning of the verb.

-

(5)

Several influential classifications of the semantic change that happens in conversion have been proposed for English (e.g., Marchand, 1969; Adams, 1973; Clark & Clark, 1979; Cetnarowska, 1993; Plag, 1999; Gottfurcht, 2008). Generally, they are based on meaning paraphrases, as is demonstrated in the following examples, which show how some of the authors classify denominal converted verbs meaning roughly “to be / act as what is denoted by the noun”, such as bully.v, butcher.v, chauffeur.v:

-

Marchand (1969): bully.v with the paraphrase “to be a bully, act as a bully”, categorized as ‘Predicate – Subject Complement’ based on the grammatical function of the noun in the paraphrase;

-

Clark and Clark (1979): butcher.v in John butchered the cow. with the paraphrase “John did to the cow the act that one would normally expect [a butcher to do to a cow]”, categorized as ‘Agent verb’ based on the agentive case the noun has in the paraphrase;

-

Plag (1999): chauffeur.v with the paraphrase “to act like a chauffeur”, categorized as ‘similative’;

-

Gottfurcht (2008): butcher.v with the paraphrase “act like N”, categorized as ‘similative’ with the lexical conceptual structure ‘BE [noun base]’.

The classifications are similar in essentially relying on meaning paraphrases, but differ in certain aspects. They work with different levels of syntactic analysis of the meaning paraphrase – Marchand (1969) is concerned with the grammatical function (subject, object, subject complement etc.) that the noun has in the meaning paraphrase, Clark and Clark (1979) refer to Fillmore’s case roles, Gottfurcht (2008) refers to the verbs’ the lexical conceptual structure. The level of detail with which the individual categories are defined also differs across authors (cf. for example Plag’s (1999) similative “to act like” vs. stative “to be” categories, which are not distinguished in the other classifications).

Authors who have applied the categories based on meaning paraphrases on larger data samples (e.g. Gottfurcht, 2008; Valera, 2020) showed that they have some problematic aspects. In the process of annotation, there is often more than one paraphrase available for a given item, especially in words with more abstract meanings (cf. e.g. Gottfurcht, 2008: 16). On the other hand, for some items in the data, no category seems to be applicable (Gottfurcht, 2008: 100–101; Valera, 2020: 325). Also, the use of paraphrases does not always ensure the same level of detail in differentiating individual meanings in context. The use of paraphrases is even more problematic in cross-linguistic comparison, as paraphrases are necessarily language-specific.

Some previous attempts at the comparison of conversion across languages can be found in e.g. Cetnarowska (1996), Don (2005), Manova (2011), Bloch-Trojnar (2013), Ševčíková and Hledíková (2022), Villalva (2022). However, either they focus on a specific data sample (e.g., deverbal masculine nouns in Cetnarowska, 1996, conversion pairs with direct formal counterparts in English in Ševčíková & Hledíková, 2022) or the focus is not on the semantic types of conversion. To the best of our knowledge, studies focusing specifically on the comparison of the semantic types of conversion in different languages have not been carried out.

For a cross-linguistic comparison of the semantics of conversion, a classification based on semantic categories applicable across languages is needed. The issue of comparative concepts based on generalizations which make use of conceptual-semantic concepts has been raised by Haspelmath (2010) in the context of typological comparison in general, and taken up in relation to the meaning of derivational affixes by Bagasheva (2017) and Körtvélyessy et al. (2020). For the comparison of conversion to be carried out on the level of conceptual categories, similarly to the comparison of derivation, we consider a cognitive approach to be appropriate.

2.3 Cognitive approach to semantic types of conversion

The cognitive approach is relevant for cross-linguistic comparison because of its focus on how common human knowledge about frequently recurring situations is categorized into generalized conceptual structures and expressed in language. Using conceptual categories that speakers of different languages are assumed to have in common, it is possible to show the differences in the particular linguistic expression of the common conceptual content in individual languages.Footnote 1

In cognitive approaches, conversion is described in terms of conceptual metonymy (e.g., Kövecses & Radden, 1998: 54–61; Dirven, 1999; Buljan, 2004; Schönfeld, 2005; Martsa, 2013). Cognitive accounts of metonymy work with basic conceptual structures which are the result of categorization and conceptualization of experience (e.g., Lakoff, 1987: 68), called different names in different proposals – e.g., “frame, schema, script, global pattern, pseudotext, cognitive model, experiential gestalt, base, scene” (Croft & Cruse, 2004: 8). Metonymy is then described as the relationship between the elements inside one conceptual schema (as opposed to metaphor, which is based on conceptual mapping between several different schemata, cf. e.g. Lakoff & Johnson, 1980).

Conversion can then be seen as an instance of such a metonymic relationship. In their theoretical study of metonymy, Kövecses and Radden (1998: 54–56) approach conversion between verbs and nouns as a pairing of two concepts in which one concept (the vehicle) provides mental access to another concept (the target) (ibid.: 39–41). Specifically, the relationship between the verb and the noun in a conversion pair is described as the relationship between two parts of an event schema (or an idealized cognitive model ‘ICM’ of an event, in their terminology), namely the “relation or predicate” (i.e., the action in an Action ICM) and “one of the participants” (ibid.: 54). The ICM of an event is a generalized mental model of a certain type of event (e.g., action, perception, causation, control etc.) which is made up of a variety of participants – for example the action ICM includes participants such as the agent, instrument, result – and a given participant may be related to the action expressed by the predicate by a metonymic relationship. For example, the relation between ski.n and ski.v is described as instrument for action metonymy. The authors explicitly link their description of denominal converted verbs to Clark and Clark’s (1979) classification (Kövecses & Radden, 1998: 60–61), as shown in Table 1.

Dirven (1999) presents a slightly different proposal featuring another set of event schemata (action schema, location/motion schema, essive schema) and participants (patient, instrument, manner, place, source, path, goal, class membership, attribute) which are thought to underlie conversion. However, the general claim is similar: based on general cognitive principles, certain participant of the underlying event schema becomes the most salient and comes to metonymically stand for the schema as such.

Martsa (2013) further develops Kövecses and Radden’s (1998) proposal using English conversion data. While Kövecses and Radden’s account focuses mostly on denominal verbs, here more attention is paid to other types of conversion. For nouns converted from verbs, along with Kövecses and Radden’s action for agent, action for object involved in the action and action for result categories, 8 additional types of metonymies are postulated (Martsa, 2013: 183–184):

-

action for the patient involved in that action (e.g., buy.n)

-

action for the instrument that is used to perform that action (e.g., lock.n)

-

action for the event involving that action (e.g., break-in.n)

-

action for an instance of that action (e.g., kick.n)

-

action for the location of that action (e.g., stop.n)

-

action for the time of that action (e.g., finish.n)

-

action/process for the sensation caused by that action/process (e.g., smell.n)

-

process for the state caused by that process (e.g., delight.n)

This cognitive approach has been applied to Czech as well, however not specifically to conversion. Janda (2011) presents a semantic classification of all suffixal word-formation in Czech, Norwegian and Russian based on types of metonymy. Following Janda, Bednaříková and Novotná (2019) describe Czech nouns created by different word-formation processes in similar terms. However, no study has focused on the cognitive description of semantic types of Czech conversion so far.

As the concrete set of schemata and their elements used for the analysis differs across different proposals and the specific set of categories used in particular proposals is not further motivated, we decided to use the typology of event schemata proposed in the Cognitive English Grammar (Radden & Dirven, 2007) for describing the semantic relation between the noun and the verb in the conversion pair. In line with previous literature, the authors understand event schemata as representations of generalized situations which are defined by the basic configurations of participant roles (such as agent, theme, etc.). In this typology, the inventory of event schemata fall under three basic “worlds of experience” (ibid.: 272), which represent the main areas where events may take place in the extra-linguistic reality. This reflects the fact that the schemata are the result of the way humans categorize and conceptualize their experience with the world. The three worlds of experience are listed in Table 2 along with the event schemata that they include. The authors are then mostly concerned with how the event schemata are reflected in syntactic constructions, i.e., how they are typically expressed by different sentence types. In contrast to the previous cognitive studies of conversion, using this framework has the advantage of connecting the conceptual categories to a typology of real-world situations, which has been established for the description of recurring syntactic patterns, rather than simply giving a list of categories.

The previous cognitive treatments of conversion assume either the denominal or deverbal direction for each pair, and some focus only on denominal verbs. In contrast, the approach presented here is non-directional – we do not specify whether the verb or the noun in the conversion pair is thought to be primary. The level of abstraction given by the cognitive schemata makes it possible to only specify which event schema is denoted by the verb and which event schema element is denoted by the noun, leaving the direction of conversion aside. This is advantageous due to the difficulty of determining the direction of conversion (cf. Sect. 2.1), which is even more pronounced in a cross-lingual setting.

In the following section, we describe the specific way of applying the typology of event schemata to annotate our data samples with semantic labels.

3 Method

3.1 Data

We applied the classification to 300 conversion pairs in English and 300 conversion pairs in Czech. The pairs are random sub-samples of conversion pairs extracted from large text corpora, namely from the British National Corpus (BNC consortium 2007) for English and from the SYN2015 corpus (Křen et al., 2015) for Czech. For more information about the size and composition of the corpora, see Table 3.

Due to the formal identity of the citation form of nouns and verbs in English, it was possible to extract the English pairs automatically. For the Czech pairs, the Morfio tool (Cvrček & Vondřička, 2013) was used for the extraction to capture all possible combinations of the verbal thematic suffixes and the nominal inflectional endings, as well as to account for morphographemic alternations. In some cases, the noun corresponds to an aspectual pair of two verbs that contain different thematic suffixes expressing the perfective vs. imperfective aspect (cf. e.g. nakoupit / nakupovat ‘purchase.v’, potáhnout / potahovat ‘cover.v’ in Table 4); in these cases, conversion was analyzed as a relation between a noun and a pair of related verbs, rather than a single verb (nákup ‘purchase.n’ – nakoupit / nakupovat ‘purchase.v’, potah ‘cover.n’ – potáhnout / potahovat ‘cover.v’).Footnote 2 No condition on the frequency of the extracted lemmas was applied in the initial extraction, nor was the origin of the words taken into account. No items were excluded due to their being borrowed from another language – from the synchronic point of view taken in this paper, loan words are considered to be an integral part of the lexicon of a given language and to be involved in its word-formation system (cf. Dietz, 2015; Eins, 2015).

The pairs were then manually annotated with labels capturing the semantic relationships between the verbs and nouns using the categories introduced in Sect. 2.3 and described in more detail in the following Sect. 3.2. In the process of semantic annotation, we used a dictionary-based approach. That means we got information about the meanings of the verbs and nouns in conversion pairs using their dictionary entries.

For Czech, a combination of two dictionaries was used: Slovník spisovného jazyka českého [Dictionary of standard Czech language] (SSJČ; Havránek et al., 1971) and Nový akademický slovník cizích slov [New academic dictionary of foreign words] (NASCS; Kraus et al., 2005). SSJČ is the largest available dictionary of contemporary Czech comprising about 190,000 entries. For cases of foreign items which may not be available in SSJČ, it was supplemented by the NASCS, which is a dictionary of words borrowed into Czech from other languages.Footnote 3 For English, we used the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Online 2023) which comprises about 230,000 entries and is comparable to SSJČ in size, as well as the level of granularity in entries’ sense description.

About a fourth of the Czech pairs (77 out of the 300) in the data sample was not found in either of the two dictionaries, and about a fourth of the English pairs (88 out of the 300) was not found in the Longman Dictionary. Therefore, another random sample was generated from the data in the same fashion as when generating the original batch of conversion pairs for analysis, and it was used to supplement the removed pairs not recorded in the dictionaries to arrive at a final sample of 300 pairs in each language (all of which are covered by the respective dictionaries).

3.2 Semantic annotation

In annotating the conversion pairs in the Czech and English sample, our basic assumption is that the verb denotes a certain type of a generalized situation, i.e., a certain event schema, and the noun denotes a role in that situation, i.e., an event schema element, or the event schema as a whole (we call this meaning instance of action/process, following Martsa, 2013).

The event schemata from Radden and Dirven (2007), which are used as the basis for the semantic annotation, are listed in Table 4, along with their descriptions and examples of how we apply them on the English and Czech conversion data.Footnote 4

As has been mentioned in the previous section, our classification abstracts from the direction of conversion. So, for example, both the pair saw.n – saw.v and whisk.v – whisk.n have the same label (‘action schema, instrument’) although the criterion of semantic dependence may lead us to postulate the denominal direction for the first pair and the deverbal direction for the second pair based on the definitions found in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED Online 2022) (saw.v “to cut with a saw” vs. whisk.n “something used for whisking”). As demonstrated e.g. by Tribout (2020), the semantic relations are often reversable in principle, and the opposite meaning paraphrases saw.n – saw.v and whisk.v – whisk.n are also imaginable: saw.n “the instrument used for sawing”, whisk.v “to use a whisk”. There are also cases in which the morphological structure of the word clearly indicates the denominal or deverbal direction, but which are semantically parallel; for example, the denominal direction in experiment.n > experiment.v is indicated by the nominal suffix -ment, while the deverbal direction in reuse.v > reuse.n is indicated by the verbal prefix re-, but the two pairs both express the same semantic relation between an action (denoted by the verb) and an instance of that action (denoted by the noun). Such cases would have the same semantic label (‘action, instance of action/process’) in our annotation.

The annotation procedure was carried out using sense definitions of the verb and noun in each conversion pair. We looked at which senses of the verb and the noun in the conversion pairs are related,Footnote 5 and then we categorized these senses into the conceptual categories based on the event schemata (described in Sect. 2.3), using the specific formulations of the sense definitions as much as possible. The SSJČ tends to use definitions with consistent wording to express the meanings of motivated words – for example, denominal verbs which include the phrase “dělat N” ‘do, make N’ (e.g., šprýmovat ‘joke.v’ = “dělat šprýmy” ‘make jokes’) or “provádět N” ‘perform, carry out N’ (e.g., manévrovat ‘maneuver.v’ = “provádět manévr” ‘perfom a maneuver’) were classified as the ‘action schema, instance of action/process’ in our classification. This makes it possible to rely on the wording of the definitions for consistent label assignment. The Longman Dictionary uses definitions which mostly do not explicitly express the semantic relationship to the motivating word in a consistent way. Therefore, an additional dictionary was used for English at this point in the annotation procedure, namely the Oxford English Dictionary (OED Online 2022), where the sense definitions do consistently use phrases expressing the semantic relationship to the motivating word. The sense definitions from the Longman Dictionary were mapped onto the definitions in OED and the wording in OED was used as support for assigning the semantic labels. For example, the sense definition of lick.n from the Longman Dictionary “when you move your tongue across the surface of something” was mapped onto the OED definition “an act of licking” and assigned the label ‘action schema, instance of action/process’. Senses labelled in either dictionary as archaic, slang or dialect were not considered. Senses only found in the OED but not in the Longman Dictionary were not included. Concrete examples of how sense definitions are used for the assignment of semantic labels to the conversion pairs in the data samples are given below in Tables 5 and 6.

This method allows for cross-linguistic comparison on a common basis and a consistent level of abstraction, because 1) the SSJČ (supplemented by NASCS) and the Longman Dictionary are of similar size, and 2) the label assignment was carried out, as much as possible, based on the wordings of dictionary definitions which express the semantic relationship of the verb and the noun in the conversion pair (definitions from SSJČ and NASCS for Czech, definitions from the OED for English). Because the dictionary definitions are mapped onto the previously outlined conceptual categories, this allows us to deal with the differences in the granularity of sense description in different dictionaries, as well as to look away from differences in lexical meaning not relevant for the description of the semantic relations between the verbs and nouns. The list of specific phrases which led to the assignment of each label can be found in the Appendix (provided via a link in the Supplementary material section).

The fact that the nouns and verbs in conversions pairs are often polysemous may lead to multiple semantic relations existing between the noun and the verb in a single conversion pair. This has been pointed out by previous authors, cf. for example:

-

“(…) eel, which can mean ‘fish for eel’ or ‘to move ... like an eel’ (…). Crew can mean ‘act as a (member of a) crew’ or ‘assign to a crew’ (…)” (Plag, 1999: 221)

-

“The noun cut denotes the result of cutting (i.e. a wound) in the sentence He made a cut in his hand: a few drops of blood trickled from it but seems to have an actional reading in the sentence The soldier made a cut at his enemy with a sword but missed.” (Cetnarowska, 1993: 97)

Our classification reflects this – if the polysemy of the verb or the noun (or both) means that the verb can denote multiple different event schemata or the noun can denote multiple different elements (or both), the conversion pair receives multiple different labels. There can be a one-to-one, one-to-many/many-to-one, or many-to-many relationship between the related senses of the verb and the noun in the conversion pair, as is demonstrated on examples in Table 5, which leads to the assignment of either one or multiple semantic labels, as is presented in Table 6.

In the English pair pot.v – pot.n, the related senses of the verb and noun all fall under a single label: ‘caused-motion schema, goal’. In whistle.v – whistle.n, the senses of the verb always fall under the ‘action schema’, however, the noun has two senses related to those of the verb which fall under two different labels: instance of action/process and the instrument. Wrinkle.v and wrinkle.n demonstrate the opposite situation in which the related senses of the verb and noun lead to the assignment of two different schemata to the verb (occurrence schema and action schema), but a single element to the noun (result). The pair sweep.v – sweep.n demonstrates a situation in which the different related senses lead to the assignment of multiple labels both in the verb and in the noun.

4 Results

4.1 Individual semantic relations

In presenting the results of the analysis, we will start by looking at the semantic relations individually, as one-to-one combinations of the conceptual meanings of the verbs and nouns in the conversion pairs. Roughly the same number of individual semantic relations was found in the data samples of both languages. For the 300 English pairs, a total of 399 semantic relations was found, and for the 300 Czech pairs, there were 387 semantic relations. Table 7 shows all the types of semantic relations found in the data and how many times they were recorded for English and for Czech. In the data, there are instances of conversion pairs where the noun expresses a non-participant role in the event schema of the verb, namely degree (e.g., yield.n ‘how much is yielded, the amount yielded’), manner (e.g., dance.n ‘a type, manner of dancing’), and possibility of action (e.g., access.n ‘the permission, opportunity, possibility to access a place’). Therefore, these event schema elements are also included in the semantic labels and can be found in Table 7.

To show the differences between the two languages, Fig. 1 presents the total number of times each element label was assigned to the nouns in the English and Czech data (out of the total number of element labels in each language, expressed in percentages).

In both English and Czech, the instance of action/process label is by far the most frequent (assigned 108 times, which is 27% of all relations, in English, and 147 times, which is 38% of all relations, in Czech), followed by the result label (assigned 75 times, i.e. 19%, in English and 87 times, i.e. 22%, in Czech). It should be noted that although the instance of action/process is the most frequent label in both languages, its proportion among all the labels is considerably higher in Czech. There are also clear differences between the two languages in how often certain labels are assigned, namely the goal, instrument and theme labels, which are more frequent in English, and the agent label, which appears more frequently in Czech.

The goal label was assigned 23 times (6%) in English, but only 4 times (1%) in Czech. This difference lies within the ‘caused-motion schema’ – the English data includes more pairs with verbs denoting the action of putting/moving something to the location named by the noun (e.g., bench.v, pigeonhole.v, table.v) than the Czech data (where only two such pairs were found: registr ‘register.n’ – registrovat ‘register.v’, směr ‘direction’ – směrovat ‘direct.v’). Similarly, the instrument label was also assigned more often in English (58 times, 15%) than in Czech (30 times, 8%). The difference lies within the ‘action schema’ – the English data contain more verbs denoting the action of using what is denoted by the noun (e.g., axe.v, bayonet.v, hammer.v) than the Czech data.

Another difference was found in the theme label, which was assigned 51 times (13%) in English, but only 28 times (7%) in Czech. The main difference can be found in pairs which belong to the ‘caused-motion schema’ and ‘transfer schema’. Within the ‘caused-motion schema’, the difference is caused by a higher number of verbs denoting the action of putting what is denoted by the noun somewhere (e.g., ornament.v, crown.v, festoon.v, fuel.v) or removing what is denoted by the noun from somewhere (e.g., core.v, husk.v); the latter of which was found exclusively in the English data. Within the ‘transfer schema’, the difference lies in a higher number of verbs denoting the action of giving somebody what is denoted by the noun (e.g., award.v, credit.v, ticket.v) in English.

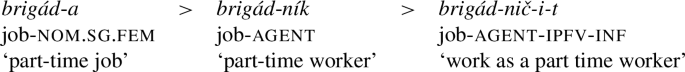

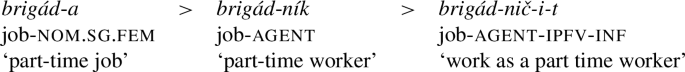

The agent label was found more frequently in the Czech data. It was assigned 28 times (7%) in Czech and 13 times (3%) in English. There is a subgroup of Czech conversion pairs that stands out as the possible underlying reason – namely, these are pairs featuring denominal verbs meaning ‘to act/work as N’ where the motivating noun is already a derived noun (cf. example 6).

-

(6)

4.2 Patterns of multiple semantic relations

So far, we have compared the individual semantic relations found in the data. In this section, we will look at the conversion pairs as whole lexemes and examine how often there are multiple semantic relations between the verb and the noun in a single pair and the patterns of semantic relations that appear together.

Figure 2 shows how many semantic relations were recorded for how many conversion pairs in the data. In both languages, about 3/4 of the pairs are linked by only one semantic relation, although there are slightly more of them in Czech (230) than in English (219), and about a fifth of the pairs have two semantic relations, although slightly more of them were found in English (67) than in Czech (56). The number of semantic relations found in a single conversion pair goes up to five in the English data (but only with a single pair) and up to four in the Czech data (with two pairs).

If we look at the pairs for which multiple relations were recorded, 99 different types of combinations were found in the English data, and 71 were found in the Czech data, which means that the types of combination are more diverse in English. Most of the combinations appeared only once in the data for both languages (68 out of the 99 in English, 47 out of the 71 in Czech). The combinations which were found repeatedly, for at least two pairs in at least one language, are listed in Table 8.

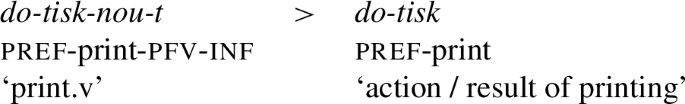

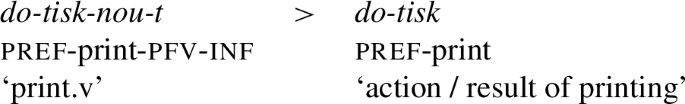

In Czech, the most frequent combination is clearly ‘action, instance of action/process + action, result’, recorded for significantly more pairs than in English. It was found mostly in pairs made up of prefixed verbs and denominal nouns, e.g., dotisknout/dotiskovat ‘reprint.v’ – dotisk ‘reprint.n’, nakoupit/nakupovat ‘purchase.v’ – nákup ‘purchase.n’, nařezat/naříznout ‘cut.v’ – nářez ‘cut.n’. Out of the total of 71 Czech pairs with multiple semantic relations, 22 have this combination, i.e., almost a third. In English, no such combination stands out among the patterns – the most frequent combination ‘action, instance of action/process + action, instrument’ was found 7 times. The ‘action, instance of action/process + action, result’ combination was only found 3 times in English, which makes it much less prominent than in Czech.

Overall, the English data includes only slightly more conversion pairs with multiple semantic relations than the Czech data, however, the combinations seem to be more varied in English than in Czech, where one frequent combination clearly stands out (‘action, instance of action/process + action, result’).

5 Discussion

The results of the analysis showed that the semantic categories that have been defined based on the cognitive schemata cover the whole range of semantic relations in both language samples. Both languages seem to mostly utilize the same categories from the set of categories that are possible based on all the relations within the cognitive schemata – although there are categories only found in the data for one language (e.g., ‘location schema, theme’, ‘perception schema, possibility of action’ only in the Czech sample; ‘occurrence schema, theme’, ‘self-motion schema, means’ only in the English sample), the number of occurrences of these categories is small also in the language where they do appear, and their absence in the sample of the other language seems to be due to the limited size of the sample rather than the impossibility of forming these pairs in the other language (examples of conversion pairs from the missing categories can be thought of, e.g., neighbour.n – neighbour.v: ‘location schema, theme’,Footnote 6view.n – view.v ‘perception schema, possibility of action’Footnote 7 in English; koruna ‘crown.n’ – korunovat ‘crown.v’: ‘occurrence schema, theme’Footnote 8, pádlo ‘paddle.n’ – pádlovat ‘paddle.v’: ‘self-motion schema, means’Footnote 9 in Czech). These results suggest that the presence (in Czech) or absence (in English) of the overt inflectional markers in conversion does not limit the range of meanings expressed.

The high proportion of conversion pairs in which the noun denotes an action is especially striking in Czech, but is also the most frequent semantic type in English. The clear prevalence of the actional meaning is in accordance with previous findings – Lieber and Plag (2022) found that 56% of the sample of English nouns converted from verbs denoted an event, and the actional meaning is considered primary both for English (e.g. Cetnarowska, 1993: 88) and Czech (e.g., Daneš et al., 1967: 244–294; Štícha et al., 2018: 440). As remarked by e.g. Cetnarowska (1993: 20), “[n]ominalisations in actional (predicative) readings can be usually replaced in sentences by appropriate verbal expressions”. The main function of converted nouns expressing the instance of action/process meaning is thus that of “syntactic recategorization” (Kastovsky, 1986), because they make it possible to refer to actions using nominal phrases in syntactic contexts which require it. The high frequency of the resultative meaning, which is the second most attested category in both languages, is in accordance with the claim that the choice of the event schema element that is denoted by the noun in a conversion pair is governed by general cognitive principles of relative salience (Kövecses & Radden, 1998: 62–63; Dirven, 1999), in this case the general orientation towards the goal or purpose of an action (i.e., “a natural psychological bias toward the goals (and purposes) of human actions”, Stefanowitsch & Rohde, 2004: 251). In sum, the tendency for nouns in conversion pairs to name actions and results seems to be independent of the morphological characteristics of the given language and rather governed by these more general principles.

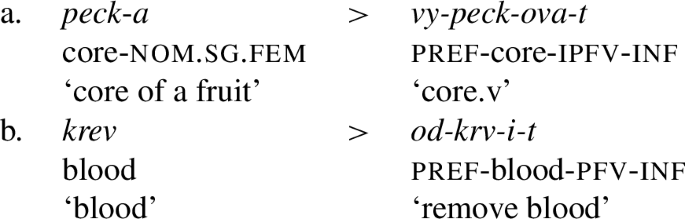

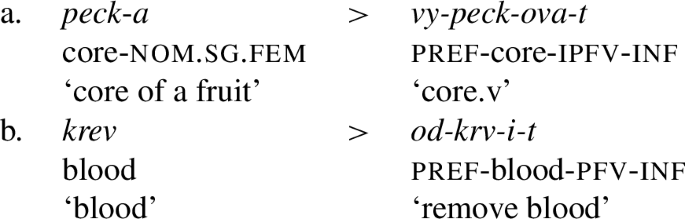

However, there are several important differences in the frequency with which some of the relations appear in each language. Especially marked is the difference in the larger number of English pairs where the noun expresses the theme, instrument and goal. The differences seem to be at least partially connected to the higher productivity of other types of word-formation processes which compete with conversion for this meaning in Czech.

As described in Sect. 4, some of the subtypes of the theme category are missing in the Czech sample. Pairs in which the verb expresses removal of what is denoted by the noun (e.g., core.n – core.v, husk.n – husk.v) were found only in English. In Czech, to form verbs with this meaning a prefix with a privative meaning (vy-, od-) is usually added (cf. examples 7a, 7b) and verbs without this prefix are rare.

-

(7)

Similarly, cases where the theme denotes a human patient were also not found in the Czech data. The prevalent word-formation pattern for nouns denoting a human patient in Czech is derivation using the suffix -ec (cf. example 8), and it seems that this pattern in not in competition with conversion. In English, suffixation by -ee (e.g., empoloy > employee) is also employed for the creation of this semantic subtype, but it does compete with conversion (e.g., initiate.v > initiate.n).

-

(8)

An annotation experiment (Ševčíková et al., 2023) carried out on Czech corpus concordances of the complete sample of Czech conversion between nouns and verbs supports the claim that the subtype of conversion where the noun denotes the removed theme and the human patient is very rare in Czech. We suggest that this is because Czech prefers the use of prefixation and suffixation for naming these concepts; however, the competition of conversion with other word-formation processes is not the focus of this study and this claim would have to be supported by a larger data analysis.

There are also large differences in the counts of the instrument and goal labels. These cannot easily be explained by competition with other word-formation processes. Denominal verbs meaning ‘to use what is denoted by the noun as an instrument’ were found frequently in English perhaps because this type has no competitors in other word-formation processes – as Adams (2001: 24) points out, “[s]uffixed verbs which are clearly instrumental are scarce or non-existent”. Gottfurcht (2008: 132, 135, 136) also found that the instrumental category is not very frequent in denominal verbs formed by suffixation using -ate, -ify, -ize. However, there does not seem to be a clear competitor in Czech either. It could be that Czech makes up for the smaller number of available verbs meaning ‘to use what is denoted by the noun as an instrument’ by using syntactic V + PP constructions (e.g., chytat do pasti ‘catch using a snare’ instead of forming an instrumental verb from past ‘snare.n’), but this suggestion would again have to be verified on data. Similarly, for the goal type, it may be that it is simply preferred to use syntactic V + PP combinations in Czech (e.g., dát na talíř ‘put on a plate’ instead of forming a verb from talíř ‘plate.n’), although competition with prefixation may be at play too (cf. examples 9a, 9b).

-

(9)

The higher number of conversion pairs where the noun denotes the agent in the Czech sample seems to be directly connected with the differences in the morphological type of the two languages which affect the formal characteristics of conversion. In English, derived nouns rarely undergo conversion into verbs (Bauer, 1983: 226). However, this restriction does not apply in Czech: the agent label was assigned to a number of conversion pairs which include denominal verbs converted from derived nouns (cf. example 10a). The overt verbal marker (the thematic suffix), which is put on the Czech verb after the nominal derivational suffix during conversion, seems to make this possible, since it clearly signals the verb’s word-class membership even despite the presence of the nominal derivational suffix. Pairs like journalist.n – *journalist.v in (10b) are rare in English due to the presence of the nominal derivational suffix. Because derived nouns expressing a person connected with a certain type of activity/profession are frequent, the fact that it is possible to form converted denominal verbs meaning ‘to do the activity/profession typical of the person denoted by the noun’ from them in Czech, but not in English, is responsible for the difference in the agent category.

-

(10)

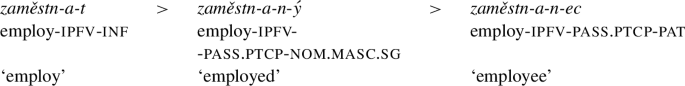

As far as the patterns of polysemy are concerned, the combinations of multiple semantic relations are less varied in Czech and the combination of labels ‘action, instance of action/process’ and ‘action, result’ clearly dominates. As has been mentioned earlier, instance of action/process and result are the two most frequently expressed categories in both languages. However, the tendency for converted nouns to express these two meanings together seems to be especially strong in Czech nouns converted from prefixed verbs. In Czech, when converting a noun from a prefixed verb, the verbal prefix enters the noun, as shown in (11). Out of the 22 Czech conversion pairs with the combination of ‘action, instance of action/process’ and ‘action, result’ labels, 14 are such pairs with a prefixed verb. The verbal prefixes in these conversion pairs make the verb oriented towards a goal or result. It seems that this resultative meaning is carried over to the converted noun, thus making the resultative meaning preferred and limiting other possible meanings (other than the primary instance of action/process meaning), leading to the prevalence of this type of combination in the Czech sample.

-

(11)

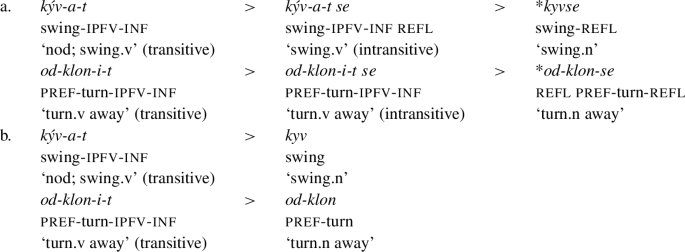

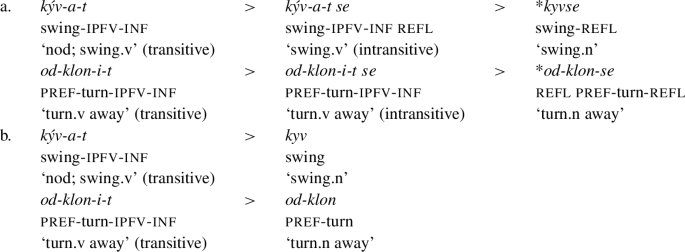

Another reason for the larger number of different types of polysemy patterns observed in the English conversion pairs is the fact that our classification distinguishes between different types of motion: self-motion (of an intentionally moving agent), caused-motion (of a theme caused by an agent), motion (of a theme by itself). There are 12 different types of polysemy patterns which include at least two different types of motion found in the English data, while only 3 such patterns are attested in the Czech data. Also, the pairs with more than 3 labels in English (curve, sweep, top) all include verbs that denote more than one of the three types of motion at the same time. This is at least in part because Czech verbs denoting the motion schema or the self-motion schema often include the reflexive morpheme se/si (cf. example 12a) in contrast to the verbs denoting the caused-motion schema, which do not have the reflexive pronoun. The reflexive verbs fall outside the scope of conversion as it is understood in this paper, because the reflexive pronoun is not able to enter into the noun (cf. the impossible nouns in example 12a) and conversion is therefore also combined with dereflexivization when the noun is formed. Only the caused-motion schema label would be given to pairs such as kývat ‘nod.v; swing.v’ – kyv ‘nod.n; swing.n’, odklonit/odklánět ‘turn.v away’ – odklon ‘turn.n away’ (cf. example 12b). Therefore, while in English, verbs of motion are often polysemous in this way and a large number of pairs have multiple labels with different types of motion, this polysemy is limited in Czech, where some of the meanings are denoted by reflexivization.

-

(12)

In summary, two main factors are hypothesized to play a role in the differences found between how often the semantic relations appear in the English and Czech sample, as well as the differences in the number of combinations of multiple semantic relations. The first factor is the competition of conversion with different word-formation processes in the word-formation system of each language (e.g., a stronger preference for forming prefixed verbs or suffixed nouns for expressing certain meanings in Czech). The second factor are some of the differences in the morphological characteristics of English and Czech. The following characteristics of Czech have been discussed: the overt marking of verbs with the thematic suffix, which makes it possible to create converted verbs from derived nouns, the resultative verbal prefixes, which are taken over from the verb into the converted noun, and the existence of reflexive verbs overtly marked with a reflexive pronoun combined with the fact that (in contrast to the verbal prefixes) the reflexive pronouns cannot be carried over from the verb into the noun.

There are several limitations to the study. Apart from its focus on only two languages and the limited size of the samples, the choice of the dictionary-based approach also has several drawbacks. One is the fact that the results are necessarily affected by the coverage of the dictionaries and the structure of the dictionary definitions. We have tried to address this issue by using dictionaries with similar size (SSJČ and Longman Dictionary) and similar conventions for describing meanings of motivated words (SSJČ and OED). Another limitation of the methodology is the fact that the frequency with which each of the documented semantic categories is used in context is not analysed. If a sense is recorded for the given word in the dictionary, it is counted as an occurrence of the corresponding semantic category, without examining how frequently the word is actually used in the given sense. Such analysis would have to be based on corpus concordances.

The study is also limited in that we are not able to further analyse the influence of word-formation processes which compete with conversion in each language. The data sample is limited to the conversion pairs, and we therefore cannot answer questions about how frequently each of the semantic categories is expressed by other means (such as words including derivational affixes, but also syntactic phrases). We have suggested that there are cases where such competition seems to have a prominent role, however, the analysis of the exact degree of its influence is beyond the scope of this paper.

6 Conclusion

We have shown that, overall, the same semantic categories cover the range of semantic relations found between the verb and the noun in the conversion pairs in both Czech and English, despite the formal differences between the two languages. The morphological characteristics of Czech and English do to some degree influence the frequency with which the individual semantic relations appear, as well as the extent to which a single conversion pair expresses multiple semantic relations. The results contribute to the theory of conversion as approached from a typological perspective (e.g., Štekauer et al., 2012; Valera, 2015) by showing the interaction between the morphological characteristics and semantic types of conversion in two languages: Czech, a language with inflectional morphology which requires overt inflectional markers on verbs, and English, a language with analytic morphological features which allows for a noun and a verb to have identical citation forms. We are aware that the results are to some degree influenced by the cognitive semantic classification of conversion chosen in the study and that because this is a case study carried out only on two languages using data samples of limited size, the results are necessarily partial. To reach more generalized conclusions, further research on larger data samples and on a wider range of languages is needed.

Data Availability

All supplementary files can be found here: http://hdl.handle.net/11234/1-5003.

Supplementary file 1: Appendix. List of dictionary definition phrases used as a basis for semantic annotation.

Supplementary file 2: English Data. Annotated English sample used for the analysis.

Supplementary file 3: Czech Data. Annotated Czech sample used for the analysis.

Notes

A similar approach to meaning is found in Jackendoff’s (1990) Lexical Conceptual Semantics framework, which also works with a repertoire of basic conceptual primitives that are supposed to formalize speakers’ mental representations (their so-called “I-conceptual knowledge”). In this approach, converted denominal verbs are described as having the base noun incorporated into one of the slots in the semantic structure of their lexical entry (Jackendoff, 1990: 54; 164–171).

There is much discussion about whether the Slavic aspect is a fully grammaticalized category and the imperfective and perfective verb in the aspectual pair are two forms of the same lexeme, or two separate lexemes (cf. e.g. Nübler et al., 2017). In this paper, we simply treat the noun as having a semantic relation to both the perfective and imperfective verb in all cases where both aspectual variants are available.

Most conversion pairs were found in the SSJČ or in both the SSJČ and NASCS, except for 13 pairs which were only found in NASCS.

The only event schema listed by Radden and Dirven (2007) but not represented in our data is the possession schema, which mainly concerns verbs such as have, own, possess.

This means that only those senses of the verb which are related to some of the noun’s senses, and vice versa, are considered in each conversion pair. This is also what is presented in Tables 4, 5, 6. Senses which are not related to any of the senses of the other word in the pair are not taken into account, as the analysis focuses on the semantic relations between the noun and verb in the conversion pair, not on all senses of the nouns and verbs and on the question of how many of the senses of the noun and verb enter conversion.

“to be a neighbour to (a person); to live next to (a person)” (OED).

“sight; the faculty or power of vision” (OED).

“jako koruna zdobit, věnčit” [to decorate as a crown, to crown] (SSJČ).

“pohánět lod’ pádlem, veslovat pádlem” [to propel a boat with a paddle, to row with a paddle] (NASCS).

References

Adams, V. (1973). An introduction to modern English word-formation. Harlow: Longman.

Adams, V. (2001). Complex words in English. Harlow: Longman.

Bagasheva, A. (2017). Comparative semantic concepts in affixation. In J. Santana-Lario & S. Valera (Eds.), Competing patterns in English affixation (pp. 33–65). Oxford: Peter Lang.

Bauer, L. (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bauer, L., Lieber, R., & Plag, I. (2013). The Oxford reference guide to English morphology. London: Oxford University Press.

Becker, T. (1993). Back-formation, cross-formation, and ‘bracketing paradoxes’ in paradigmatic morphology. In G. Booij & J. Van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 1993 (pp. 1–25). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-3712-8_1.

Bednaříková, B. (2009). Slovo a jeho konverze. Univerzita Palackého, Filozofická Fakulta.

Bednaříková, B., & Novotná, Z. (2019). Metonymy in Czech word formation in terms of cognitive linguistics. Athens Journal of Philology, 6(3), 189–200.

Bergenholtz, H., & Mugdan, J. (1979). Ist Liebe primär? – Über Ableitung und Wortarten. In P. Braun (Ed.), Deutsche Gegenwartssprache. Entwicklungen, Entwürfe, Diskussionen (pp. 339–354). Fink.

Bloch-Trojnar, M. (2013). The mechanics of transposition. A study of action nominalisations in English, Irish and Polish. Wydawnictwo KUL.

Bram, B. (2011). Major total conversion in English: The question of directionality. Victoria University of Wellington dissertation.

Buljan, G. (2004). Interpreting English verb conversions: The role of metonymy and metaphor. Contemporary Linguistics, 57–58(1–2), 13–30.

Cetnarowska, B. (1993). The syntax, semantics and derivation of bare nominalisations in English. Uniwersytet Śląski.

Cetnarowska, B. (1996). Constraints on suffixless derivation in Polish and English: The case of action nouns. In K. Henryk & B. Szymanek (Eds.), A Festschrift for Edmund Gussmann from his friends and colleagues (pp. 15–28). The University Press of the Catholic University of Lublin.

Clark, E. V., & Clark, H. H. (1979). When nouns surface as verbs. Language, 55(4), 767–811.

Croft, W., & Cruse, D. A. (2004). Cognitive linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Daneš, F., Dokulil, M., & Kuchař, J. (1967). Tvoření slov v češtině 2: Odvozování podstatných jmen. Nakladatelství ČSAV.

Dietz, K. (2015). Foreign word-formation in English. In P. O. Müller, I. Ohnheiser, S. Olsen, & F. Rainer (Eds.), Word-formation. An international handbook of languages of Europe (Vol. 3, pp. 1637–1660). Berlin: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110375732.

Dirven, R. (1999). Conversion as conceptual metonymy of event schemata. In K.-U. Panther & G. Radden (Eds.), Metonymy in language and thought (pp. 275–288). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Dokulil, M. (1962). Tvoření slov v češtině 1: Teorie odvozování slov. Nakladatelství ČSAV.

Dokulil, M., Horálek, K., Hůrková, J., Knappová, M., & Petr, J. (1986). Mluvnice češtiny 1: Fonetika, fonologie, morfonologie a morfematika, tvoření slov. Prague: Academia.

Don, J. (2005). On conversion, relisting and zero-derivation. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics, 2(2), 2–16.

Eins, W. (2015). Types of foreign word-formation. In P. O. Müller, I. Ohnheiser, S. Olsen, & F. Rainer (Eds.), Word-formation. An international handbook of languages of Europe (Vol. 3, pp. 1531–1579). Berlin: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110375732.

Farrell, P. (2001). Functional shift as category underspecification. English Language and Linguistics, 5(1), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674301000156.

Gottfurcht, C. A. (2008). Denominal verb formation in English. Northwestern University dissertation.

Hale, K., & Keyser, S. J. (2002). Conflation. In Prolegomenon to a theory of argument structure (pp. 47–105). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harley, H. (2005). How do verbs get their names? Denominal verbs, manner incorporation, and the ontology of verb roots in English. In N. Erteschik-Shir & T. Rapoport (Eds.), The syntax of aspect (pp. 42–64). London: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199280445.003.0003.

Haspelmath, M. (2010). Comparative concepts and descriptive categories in crosslinguistic studies. Language, 86(3), 663–687. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2010.0021.

Jackendoff, R. (1990). Semantic structures. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Janda, L. (2011). Metonymy in word-formation. Cognitive Linguistics, 22(2), 359–392. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.2011.014.

Kastovsky, D. (1986). The problem of productivity in word formation. Linguistics, 24(3), 585–600. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1986.24.3.585.

Kastovsky, D. (2005). Conversion and/or zero: Word-formation theory, historical linguistics, and typology. In L. Bauer & S. Valera (Eds.), Approaches to conversion/Zero-derivation (pp. 31–47). Waxmann.

Körtvélyessy, L., Bagasheva, A., & Štekauer, P. (Eds.) (2020). Derivational networks across languages. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kövecses, Z., & Radden, G. (1998). Metonymy: Developing a cognitive linguistic view. Cognitive Linguistics, 9(1), 37–78. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.1998.9.1.37.

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lieber, R. (2004). Morphology and lexical semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lieber, R. (2005). English word-formation processes. In P. Štekauer & R. Lieber (Eds.), Handbook of word-formation (pp. 374–427). Berlin: Springer.

Lieber, R., & Plag, I. (2022). The semantics of conversion nouns and -ing nominalizations: A quantitative and theoretical perspective. Journal of Linguistics, 58(2), 307–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226721000311.

Manova, S. (2011). Understanding morphological rules: With special emphasis on conversion and subtraction in Bulgarian, Russian and Serbo-Croatian. Berlin: Springer.

Marchand, H. (1964). A set of criteria for the establishing of derivational relationship between words unmarked by derivational morphemes. Indogermanische Forschungen, 69, 10–19.

Marchand, H. (1969). The categories and types of present-day English wordformation: A synchronic-diachronic approach (2nd ed.). München: C.H. Beck Verlag.

Martsa, S. (2013). Conversion in English: A cognitive semantic approach. Cambridge Scholars.

Mititelu, V., Leseva, S., & Stoyanova, I. (2023). Semantic analysis of verb – noun zero derivation in Princeton WordNet. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft, 42(1), 181–207.

Nübler, N., Biskup, P., & Kresin, S. (2017). Vid. In P. Karlík, M. Nekula, & J. Pleskalová (Eds.), CzechEncy – Nový encyklopedický slovník češtiny. Available at https://www.czechency.org/slovnik/VID. Last accessed January 04, 2024.

Plag, I. (1999). Morphological productivity: Structural constraints in English derivation. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Plag, I. (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Plank, F. (2010). Variable direction in zero-derivation and the unity of polysemous lexical items. Word Structure, 3(1), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.3366/E1750124510000498.

Radden, G., & Dirven, R. (2007). Cognitive English grammar. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Schönfeld, D. (2005). Zero-derivation – functional change – metonymy. In L. Bauer & S. Valera (Eds.), Apporaches to conversion/zero-derivation (pp. 131–159). Waxmann.

Ševčíková, M., & Hledíková, H. (2022). Paradigms in English and Czech noun/verb conversion: A contrastive study of corresponding lexemes. In A. E. Ruz, C. Fernández-Alcaina, & C. Lara-Clares (Eds.), Paradigms in word formation: Theory and applications (pp. 181–214). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Ševčíková, M., Hledíková, H., Kyjánek, L., & Staňková, A. (2023). Semantics of noun/verb conversion in Czech: Lessons learned from corpus data annotation. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics, 20(4), 74–92.

Stefanowitsch, A., & Rohde, A. (2004). The goal bias in the encoding of motion events. In G. Radden & K.-U. Panther (Eds.), Studies in linguistic motivation (pp. 249–268). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Štekauer, P. (1996). A theory of conversion in English. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Štekauer, P., Valera, S., & Körtvélyessy, L. (2012). Word-formation without addition of derivational material and subtractive word-formation. In Word-formation in the world’s languages: A typological survey (pp. 213–236). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511895005.

Štícha, F., Kolářová, I., Vondráček, M., Bozděchová, I., Bílková, J., Osolsobě, K., Kochová, P., Opavská, Z., Šimandl, J., Kopáčková, L., & Veselý, V. (2018). Velká akademická gramatika spisovné češtiny 1. Prague: Academia.

Tribout, D. (2020). Nominalization, verbalization or both? Insights from the directionality of noun-verb conversion in French. Zeitschrift für Wortbildung, 4(2), 187–207.

Valera, S. (2015). Conversion. In P. O. Müller, I. Ohnheiser, S. Olsen, & F. Rainer (Eds.), Word-formation: An international handbook of the languages of Europe (Vol. 1, pp. 322–339). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Valera, S. (2020). Semantic patterns in noun-to-verb conversion in English. In L. Körtvélyessy & P. Štekauer (Eds.), Complex words (pp. 311–334). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108780643.017.

Villalva, A. (2022). Complex verbs: The interplay of suffixation, conversion, and parasynthesis in Portuguese and English. In A. E. Ruz, C. Fernández-Alcaina, & C. Lara-Clares (Eds.), Paradigms in word formation: Theory and applications (pp. 249–282). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Language Sources

Oxford English Dictionary (2022). Oxford English dictionary online. London: Oxford University Press. Available at https://oed.com/. Last accessed May 02, 2022.

British National Corpus (2007). The British National Corpus. XML Edition. Oxford Text Archive. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12024/2554.

Cvrček, V., & Vondřička, P. (2013). Morfio. FF UK. http://morfio.korpus.cz.

Havránek, B., Bělič, J., Helcl, M., & Jedlička, A. (1971). Slovník spisovného jazyka českého. Prague: Academia.

Kraus, J., Buchtelová, R., Confortiová, H., Červená, V., Holubová, V., Hovorková, M., Machač, J., Mejstřík, V., Petráčková, V., Poštolková, B., Roudný, M., Schmiedtová, V., Šroufková, M., & Ungermann, V. (2005). Nový akademický slovník cizích slov. Prague: Academia.

Křen, M., Cvrček, V., Čapka, T., Čermáková, A., Hnátková, M., Chlumská, L., Jelínek, T., Kováříková, D., Petkevič, V., Procházka, P., Skoumalová, H., Škrabal, M., Truneček, P., Vondřička, P., & Zasina, A. J. (2015). SYN2015: Reprezentativní korpus psané češtiny. Ústav Českého národního korpusu FF UK. http://www.korpus.cz.

Longman (2023). Longman dictionary of contemporary English online. Available at https://www.ldoceonline.com. Last accessed December 13, 2023.

Funding

Open access publishing supported by the National Technical Library in Prague. The study was supported by the Charles University, project GA UK No. 246723, by the SVV project No. 260 698, and by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, Project No. LM2023062 LINDAT/CLARIAH-CZ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations: n = noun; v = verb; adj = adjective; agent = agentive; fem = feminine; ipfv = imperfective; inf = infinitive; masc = masculine; nom = nominative; pass.ptcp = passive participle; pat = patient; pfv = perfective; pref = prefix; refl = reflexive; sg = singular.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hledíková, H., Ševčíková, M. Conversion in languages with different morphological structures: a semantic comparison of English and Czech. Morphology 34, 73–102 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-024-09422-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-024-09422-1