Abstract

The particular properties of argumental compounds in Italian pose interesting theoretical challenges, and investigations of possible syntactic operations within this type of complex words have resulted in conflicting conclusions. Regarding compound-internal anaphora, some researchers exclude the possibility that pronouns can refer to the non-head, while others do not. However, these findings have been based on researchers’ intuitions and on occurrences in language corpora, and while intuitions have been shown to give contrasting results, the absence of a grammatical structure in a corpus should not be taken as evidence that the structure is not possible. The present study aims to experimentally determine the possibility of compound-internal pronominal reference based on structural properties of compounds and referential expressions. Judgements were obtained from 140 Italian native speakers who rated the acceptability of sentences containing a pronoun (null or overt) referring to the argument element of an argumental compound. The results indicate that compound-internal anaphoric reference is acceptable in the case of left-headed compounds and, to a somewhat lesser extent, of verb-noun compounds. The argument element of right-headed compounds, however, does not appear to be available to anaphoric reference. Referential expressions also play a role in the degree of acceptability, with left-headed compounds allowing null form anaphora to a greater extent. These results provide new evidence on compound-internal pronominal reference and give important insights into the processing of argumental compounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Argumental compounds in Italian show features that make them more accessible to syntax than other types of compounds. However, while most of their syntactic peculiarities are highly documented, the acceptability of pronominal reference internal to the compound has remained a disputed issue.

Generally, results suggesting the non-acceptability of compound-internal anaphoric reference in Italian are based on researchers’ intuitions or on the limited presence of this phenomenon in corpora. However, the acceptability of compound-internal anaphoric reference should not be dismissed only based on individual judgments or on the absence of certain patterns in corpus research. Both these approaches have intrinsic limits: while intuitions might change from linguist to linguist, the limited presence of compound-internal anaphora in corpora does not necessarily indicate its non-acceptability. Moreover, corpus-based analysis does not allow for more fine-grained considerations on (non-)acceptability constraints.

Drawing on the results of an acceptability judgement task, we provide evidence that Italian argumental compounds do allow pronominal reference to the argument element depending on their structure and on the quality of the referential expression (i.e., null vs overt pronoun). It is shown that the position of the head plays a decisive role, and while compound-internal anaphora is accepted with left-headed compounds and, to a minor extent, with exocentric compounds, the same is not true for right-headed compounds. Moreover, it has been found that left-headed compounds allow null-subject anaphora to a greater extent, possibly due to pragmatic factors.

Hence, the test made it possible to single out detailed variables that could not otherwise have been observed in corpus-based research. Our results show the benefit of an integration of an experimental method with theoretical considerations and corpus-based research.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides a background introduction to argumental compounds in Italian (Sect. 2.1), an overview of in-word anaphora with some conflicting positions regarding its acceptability in Italian argumental compounds (Sect. 2.2) and current issues in research (Sect. 2.3). In Sect. 3, we present our study and in Sect. 4 we discuss the results, which show that compound-internal anaphora seems to be accepted by native speakers with important differences according to the position of the head and the nature of referential expression. Section 5 presents our conclusions.

2 Background

2.1 Argumental compounds

Argumental compounds are a subtype of subordinate compoundsFootnote 1 consisting of one constituent that represents the internal argument of the other, i.e., the direct object. They have been defined according to different criteria, and are referred to using various labels in the literature, including “deverbal” or “verbal compounds” (Roeper & Siegel, 1978; Selkirk, 1982; Lieber, 2010), “synthetic compounds” (Lieber, 1994; Ackema & Neeleman, 2004; Gaeta, 2010), “verbal-nexus compounds” (Marchand, 1969; Allen, 1978; Bauer 2001, 2010; Scalise & Bisetto, 2011; Radimský, 2015); “secondary compounds” (Scalise et al., 2005) and “argumental compounds” (Baroni et al., 2009a; Bauer, 2013). Particularly, the label “verbal-nexus” has been widely used to underline the head’s deverbal nature in this type of compound.

In this study, we avoid a label focused on the morphological nature of the head and use “argumental compound”, following Baroni et al. (2009a). In fact, as Scalise and Guevara (2006) also point out, an argumental interpretation may occur even in the absence of a deverbal element, and deverbal constituents do not necessarily project argumental structure.Footnote 2

We limit our investigation to the argumental relation,Footnote 3 as syntactic considerations are at the basis of our research question and may be crucial in specific syntactic phenomena such as pronominal anaphora.Footnote 4 A basic division between argumental and non-argumental compounds was also proposed by Bauer et al. (2013) for English. The division is based on the assumption that argument structure allows a more direct interpretation, being semantically more predictable and constrained, while the interpretation of a predicate-adjunct relation is highly variable and largely determined by the context (see also Mackenzie, 1990; Haspelmath, 2002; Bauer, 2009; Guerrero Medina, 2018, among many others).

2.1.1 Structure of Italian argumental compounds

Italian argumental compounds can be endocentric, i.e., possessing the head inside the compound, or exocentric, i.e. lacking a head constituent. In argumental endocentric compounds, the head selects the non-head (e.g., donatoreHEAD sangueARGUMENT ‘blood donor’, lit. ‘donor blood’), while in argumental exocentric compounds the verbal element selects the nominal element based on argumental restrictions (e.g., lavaVERBpiattiARGUMENT ‘dishwasher’, lit. ‘washdishes’) (Scalise & Guevara, 2006).Footnote 5

In endocentric argumental compounds, a noun is selected as the internal argument by another (usually deverbal) noun or nominalization representing the head (Scalise et al., 2005):

-

(1)

In this case latte ‘milk’ is selected by the predicate indicated by the deverbal head trasporto ‘transportation’. This structure, where the head is on the left of the compound (NHN henceforth), is assumed to be the archetypal one in Italian (Scalise 1990, 1994; Bisetto & Scalise, 1999, Scalise & Fábregas, 2010) and other Romance languages, as opposed to Germanic languages (Selkirk, 1982; Scalise, 1986; Lieber, 2009; Melloni, 2020). However, it is also possible for the argument to appear as the first element.

-

(2)

In example (2), auto ‘car’ is the argument of the nominalized form noleggio ‘rental’, on the right side of the compound.

A right-headed structure (NNH henceforth) in Italian has been assumed to represent relics of Latin composition or foreign calques (e.g., frutticoltura ‘fruit farming’, scuola bus ‘school bus’, Scalise 1990, 1994; Masini & Scalise, 2012), to be restricted to a small set of nouns (e.g., auto- as in (2), Iacobini, 2004; Schwarze, 2005; Radimský, 2006; Booij, 2010), or to be subject to phonological constraints (Altakhaineh, 2019). Scalise and Fábregas (2010) claim that the right-headedness of many productive compounds (e.g., autostrada ‘highway’) represents a learned pattern where the first element is a semi-word (i.e., a learned word that has become a free lexeme), and thus a neoclassical order is present even in words that never existed in the classical languages (see also Iacobini, 2004).

Differences in processing between left- and right-headed compounds have been confirmed experimentally (El Yagoubi et al., 2008; Marelli et al., 2009; Marelli & Luzzatti, 2012; Arcara et al. 2013, 2014). However, right-headed compounds have been argued to represent a productive word-formation process in contemporary Italian (Guevara & Scalise, 2009; Marelli & Luzzatti, 2012; Radimský 2013a, 2013b, 2015). Radimský (2013b) showed that while it is true that NNH compounds often contain elements derived from neoclassical terms and belong to a specialized lexicon, nowadays they can also be formed with ordinary nouns from the common lexicon, “becoming a vital word-formation paradigm in contemporary Italian” (Radimský, 2013a:44).

Despite their debatable nature, we included right-headed compounds in our experiment in order to examine their behavior regarding word-internal anaphora to shed more light on their properties. Due to their increasing presence in the contemporary Italian vocabulary, the position of the head has been argued to be an important criterion to consider if we aim to reach an exhaustive analysis of Italian compounds (Bisetto, 2004; Radimský 2013b, 2015) and hence, for the reasons illustrated here, we believe that our experiment may help answer questions on the quality of this peculiar compound structure.

In Italian, exocentric argumental compounds have a verb + noun structure (VN henceforth). Being neither the verb nor the noun responsible for the semantic or the syntactical properties of the compound, VN compounds do not possess a head (Scalise, 1992b; Bauer, 2010; Masini & Scalise, 2012; Ricca, 2015).Footnote 6 These compounds are very productive in the Romance languages (Tekavčić, 1972; Gather, 2001).Footnote 7

The syntactic relation between the elements in Italian VN compounds is almost exclusively that of a predicate and its internal argument (see Scalise, 1992b; Scalise et al., 2009, according to whom it is precisely the argumental structure that causes exocentricity in Romance VN compounds)Footnote 8:

-

(3)

The argument of the verb can be either a direct object of a transitive verb as in (3) or a subject (e.g., batticuore, ‘heart palpitations’, lit. ‘pound heart’). However, VN compounds almost exclusively possess an agentive interpretation (Bisetto, 1994; Gaeta & Ricca, 2009; Scalise et al., 2009), and a transitive reading is the most common and productive (Bisetto, 1999).

Figure 1 shows the typology of Italian argumental compounds.

2.1.2 Properties of argumental compounds

NN argumental compounds have been widely investigatedFootnote 9 (Bisetto & Scalise, 1999; Lieber & Scalise, 2006; Delfitto & Paradisi, 2009a; Gaeta & Ricca, 2009; Baroni et al., 2009b; Bisetto, 2015). According to some authors they are not attested in Romance languages other than Italian (Baroni et al., 2009b; Delfitto & Paradisi, 2009b),Footnote 10 and within Italian, they are used predominantly in specific contexts (newspapers, advertising, bureaucratic documents, web language) and not often in spoken language (Baroni et al., 2009b; Bisetto 2010, 2015).

Their ambiguous nature, at the border between morphology and syntax, has even challenged the possibility of categorizing these structures as ‘compounds’: they are defined as ‘compound-like phrases’ by Bisetto and Scalise (1999) and Bisetto (2015)Footnote 11 and considered to be the remains of ‘juxtaposition genitives’ of early phases of the language by Delfitto and Paradisi (2009a). Baroni et al. (2009b) do not incorporate these formations within a single class. According to these authors, this structure includes regular compounds (without internal modifiers) as well as instances of “headlinese phrases” (with internal modifiers). Gaeta and Ricca (2009) and Radimský (2015), however, insist that these structures should be included in the group of subordinate compounds instead.

One feature that has been extensively debated is their transparency to insertion: these constructions allow for modification of the head (4a), the non-head (4b) or both (4c) (examples from Bisetto & Scalise, 1999):

-

(4)

Modification of the head is considered more problematic by Delfitto and Paradisi (2009a), while Gaeta and Ricca (2009) attest head modification even with non-argumental compounds. Argument modification is more common than head modification (Radimský, 2015), not only with adjectives but also with more complex NPs. Both the head and the non-head may consist of two coordinated nouns, as in (5a) with coordinated heads, in (5b) with two coordinated arguments without the specification of the second, and in (5c) where the two coordinated arguments are modified by an adjective and followed by a relative clause.

-

(5)

The acceptability of head deletion under coordination is debated. According to Gaeta and Ricca (2009), it is observed even with non-argumental compounds. Bisetto and Scalise (1999) consider (6a) marginally acceptableFootnote 12 while Lieber and Scalise (2006) consider it ungrammatical. According to Delfitto and Paradisi (2009a), it is possible only if the ellipsis is licensed by an indefinite determiner as in (6b), something that is also suggested by Radimský (2015), who notes the possibility of head deletion in absence of a determinerFootnote 13 (6c) (the examples in (6) are adapted from the ones discussed in these studies):

-

(6)

Regarding recursivity, complex embedded argumental compounds represent a marginal phenomenon. However, Radimský (2015) verifies the possibility of trinominal compounds, where an argumental compound can be embedded into another argumental or other type of compound:

-

(7)

Like NN compounds, VN compounds are not opaque to syntactic operations either. The nominal component of VN compounds can in fact be expanded in several ways. It can be modified by adjectives, complex NPs and relative clauses (Ricca 2005, 2010; Bisetto, 2015), and even by extremely complex structures (example from Gaeta & Ricca, 2009):

-

(8)

Head deletion has been observed with single, coordinated and modified nouns (Ricca, 2005) and also with very complex NPs, example from Bisetto (2015):

-

(9)

VN compounds allow for recursivity as well (example from Dressler, 1987; Bisetto, 2010):

-

(10)

2.2 In-word anaphora

In his influential paper, Postal (1969), based on introspections of his own dialectal English variety, identifies several constraints on the acceptability of pronominal anaphora, and formulates the generalization that complex wordsFootnote 14 are “anaphoric islands”, i.e., they cannot contain a subpart functioning as an antecedent for subsequent anaphora.Footnote 15 Hence, while the sentences in (11) are acceptable, those in (12) are, in his view, ungrammatical:

-

(11)

-

(12)

After Postal (1969) made the claim of word-islandhood, a debate arose: “islands” have been argued to be “peninsulas” (Corum, 1973; Browne, 1974; Lieber, 1992), suggesting that this phenomenon does not involve a categorical constraint.

Lakoff and Ross (1972) tried to individuate elements facilitating outbound anaphora to account for its tendencies and proposed, among other things, that it is more acceptable if the morphologically complex word (in this case, a derivative word) containing the antecedent does not c-command the pronoun. Therefore, (13a) is predicted to be less acceptable than (13b):

-

(13)

Their approach, arguing for ‘tendencies’ and not ‘constraints’, is shared by Dressler (1987). In fact, he points out that words’ subparts are syntactically inaccessible only if we postulate the existence of a unidirectional flow of information, advocating instead for interactional models. He stresses how problematic it is to consider a tendency as an absolute constraint with ad-hoc hypotheses created to confirm such absolutism, and notices that pronominal anaphora can indeed have as its antecedent the argument element of an argumental compoundFootnote 16 (however, limiting this possibility only to VN compounds), invoking the important role of semantic transparency, i.e., the clear decompositionality of a complex word into its parts. In fact, not only does he specify that the less tightly the lexemes are bonded, the more open to syntax they are (i.e., a structural property), but also the more semantically transparent the lexemes are (i.e., a semantic property).Footnote 17

Ward et al. (1991) consider in-word anaphora as a gradient phenomenon, completely motivated by pragmatic factors. Moreover, contrary to what is claimed by Lakoff and Ross (1972), according to Ward et al. (1991:449) neither the syntactic role of the antecedent nor the morphological relation between antecedent and pronoun are decisive for its acceptability: “the degree to which outbound anaphora is felicitous is determined by the relative accessibility of the discourse entities evoked by word-internal elements, and not by any principles of syntax or morphology”. Based on the results of an experimental study, they show that antecedents of outbound anaphora appear to be more easily accessible if already implicitly present in the discourse. They also present an interesting example with an argumental compound:

-

(14)

To account for cases such as (14), they too invoke the notion of semantic transparency. In this case, cocaine use is easily decomposed because of the interpretation of the argument structure. According to their analysis, since both the predicate use and the argument cocaine are lexically accessible, the discourse entity becomes contextually salient and therefore accessible as the antecedent for a pronoun.

2.3 Compound-internal anaphora in Italian argumental compounds

Regarding Italian argumental compounds, some opposing views have been proposed. Scalise (1992a) excludes the possibility that one element of the compound can be the antecedent of anaphora. While it is shown that a word in isolation possesses referential capacity, the same word is assumed not to feature this syntactic property when it is part of a compound (in this case a VN argumental compound):

-

(15)

Scalise (1992a) gives the example (15b) to demonstrate a postulated anaphoric islandhood of compounds. However this is not particularly felicitous since it is explainable only in terms of an abrupt change of subject. Hence, such an example would result in an ill-formed sentence even with a normal NP:

-

(16)

In Bisetto and Scalise’s (1999) analysis of argumental compounds (‘compound-like phrases’), anaphoric reference to the non-head is categorically excluded:

-

(17)

In our opinion, (17) does not provide solid proof for unacceptability, because a semantic bias (and possibly a syntactic one) may be the reason why this sentence is ill-formed. While ‘passenger transportation’ refers generically to passengers that can be transported, the act of knowing them implies in fact a specific reference. An example that presents a more natural context for the pronoun appears in fact more acceptable:

-

(18)

Delfitto and Paradisi (2009a:55-56) also argue that the ill-formedness of (17) is due to other factors than anaphoric opacity and observe that “anaphora is allowed in cases [...] where the resuming pronoun matches the referential features of the non-head constituent to be resumed”:

-

(19)

However, example (19) differs in two ways from Bisetto and Scalise‘s (1999) example (17) which may explain its acceptability. First, the compound does not c-command the anaphora, something that arguably hinders in-word anaphora (Lakoff & Ross, 1972). Second, the referring element questi ultimii ‘the latter’ is not a pronominal form, but a full NP, something that is argued to facilitate in-word anaphora (Montermini, 2006). For these reasons, example (19) does not represent true counterevidence to (17).

Lieber and Scalise (2006) reject the possibility of compound-internal pronominal anaphora for NN compounds based on the example (17) proposed by Bisetto and Scalise (1999). They acknowledge the long dispute regarding the Lexical Integrity Hypothesis and coreference into complex words, stating that “further investigation is needed on various factors which seem to influence judgments, including differences between derivation and compounding, the type of syntactic construction involved, the typology of the language in question, the productivity of forms, and so on” (Lieber & Scalise, 2006:12).

Radimský (2015) points out that the comparisons between anaphora in argumental compounds in opposition to phrases by Bisetto and Scalise (1999) cannot give insights into the relation between morphology and syntax. They compare (17) to (20):

-

(20)

As Radimský (2015) observes, while in (20) the anaphora is governed by a full DP del latte ‘of the milk’, in (17) it concerns a bare noun. However, he does not consider pronominal reference to the non-head acceptable, although he admits the presence of some evidence in corpora ‘under certain circumstances’ which he explains in terms of discourse phenomena rather than syntactic properties, in agreement with Montermini (2006). He shows an example from Bisetto (2004), who admits that “pronominal reference to the non-head constituent is sometimes possible, even though in sentences that are often peculiar” (Bisetto, 2004:35, our translation from Italian):

-

(21)

Bisetto (2004) also states that these structures show no variability in the relation between the constituents, underlining the peculiarity of argumental compounds. Example (21) is cited by Masini and Scalise (2012) as well, to show the anaphoric capacity of non-head elements of NHN compounds. However, they do not consider pronominal anaphora with VN compounds acceptable.

-

(22)

It is interesting to notice that a similar example was used by Dressler (1987) to precisely show its acceptability:

-

(23)

Radimský (2015) who does not accept compound-internal anaphora with NN compounds, also gives an example from Grandi (2006) to represent an exception, concerning precisely VN compounds.

-

(24)

Grandi (2006:34) describes the structure of VN compounds as showing “a rather low degree of syntactic atomicity, since, in violation of the Lexical Integrity Hypothesis, it allows the relativization of the sole second constituent” (see also Gaeta & Ricca, 2009; Ricca, 2010 for similar considerations). Grandi (2006) also points out that examples such as (24) show that this phenomenon not only is acceptable with new formations but also with compounds that are well established in the lexicon. Regarding the syntactic behaviour of new formations, Ricca (2005) notices that corpora show a permeability of VN compounds to syntax even with nonce words:

-

(25)

Ricca (2005) underlines that a closer look at new formations can provide insights into formation rules since these instances are not stabilized in speakers‘ mental lexicon and hence are not formed by idiosyncratic semantic evolutions.

Arcodia et al. (2009) consider the phenomenon unusual but do not dismiss it as unacceptable. On the contrary, they acknowledge how the referential capacity of one element strongly challenges views of grammar where syntactic rules apply only after morphological rules. Baroni et al. (2009b) define the referential capacity of the non-head as one of the peculiar properties of NN argumental compounds, underlining the difference with English, where pronominal reference is not acceptable:

-

(26)

A thorough discussion of the possibility of outbound anaphora in Italian complex words is presented by Montermini (2006). This study analyzes the phenomenon in general, including several kinds of complex words and referential expressions. The author underlines that demonstratives and full NPs are more acceptable than pronouns, since these involve less referential ambiguity, as in (19). He also points out that the hypothetical universal parameter by Dressler (1987), according to which compounds are more transparent to syntax than derivatives (i.e., complex words created by adding bound affixes to a root instead of to free lexemes) is uncertain, as in Italian it appears to be valid for VN compounds much more than for NN compounds. An explanation, according to the author, is the prominent presence of coordinative compounds: the elements of this compound type are in fact on the same syntactical level, and this would favour referential ambiguity and hence discourage its acceptance. This would thus imply an unbalanced presence of the phenomenon in corpora, rather than a structural difference in acceptability for VN compounds as opposed to NN compounds.

2.4 Current issues

Even though the previous studies represent important investigations of Italian compounds, we believe that neither single intuitions nor corpus-based methods can answer the question whether compound-internal pronominal anaphora is acceptable and whether there are degrees of acceptability caused by the structure of the compound and the quality of referential expression (see the review on the limits of corpus research by Dash & Ramamoorthy, 2019, among others). Experimental evidence is essential to address these topics (see Myers, 2017 on the importance of acceptability judgments).

A methodological issue seems to lie at the basis of this uncertainty in the literature. Many researchers draw conclusions based on their intuitions which are typically based on theoretical stands. In addition to theoretical reflections based on intuitions, much research on Italian compounds is based on corpora. Even though corpus research on Italian compounds has provided and continues to provide important insights (see among many others, the impressive work of Radimský, 2015), it may not be the best method to investigate specific research questions such as the acceptability of compound-internal pronominal anaphora. As Micheli (2016) underlines, the use of corpora in the investigation of Italian compounds is a challenging research method: compounds in Italian are relatively rare lexical entities, and tend to be used in restricted contexts (this appears to be particularly true for argumental compounds (Baroni et al., 2009a,b; Bisetto 2010, 2015)). Due to their low frequency, it is hard to record sufficiently many occurrences to let linguists draw conclusions on specific phenomena.

Moreover, negative evidence (or weak positive evidence) in corpus-based research, as Baroni et al. (2009a,b) point out, does not necessarily mean that a phenomenon is unacceptable, because it may reflect other types of bias such as stylistic preferences or pragmatics-related factors.

An experimental investigation of anaphoric reference, however, can answer specific questions, and provide insights into structural differences regarding compounds as well as referential expressions. This is of crucial importance, especially when reflecting on the conclusions drawn by previous studies. As described in the previous section, Montermini (2006) states that NN compounds are statistically more open to anaphoric reference than VN compounds, based on the high frequency of coordinative NN compounds (which have no dependency relation between the elements, and hence the reference would be ambiguous).

Montermini (2006) expresses doubts on acceptability judgements, stating that these are subject to variation. This variation is what we are specifically interested in since it appears that we are dealing with tendencies and cannot expect clear-cut answers. He also points out that real instances of word-internal anaphora would be considered unacceptable in an acceptability judgement task. We agree that metalinguistic reflections tend to be more prescriptive in nature; however, we wonder if this could be prevented by explicitly asking informants to think about informal contexts. Finally, if what Montermini (2006) states is true, we can safely assume that our results underestimate the phenomenon, which would mean that the phenomenon is even more acceptable than what our data suggest.

Acknowledging the importance of pragmatic factors (Montermini, 2006; Ward et al., 1991), an acceptability judgment task allows us to maintain the same structure for the target sentences, so that informants are not biased by differences in information packaging. In every sentence, the pronoun clearly refers back to an element of the compound, and we only ask to rate the acceptability of the utterance. Moreover, based on Montermini’s (2006) observations on the role of the referential expression, we only used overt direct object pronouns and null subject pronouns, but no demonstratives or full NPs. The fact that less ambiguous referents are more acceptable than pronouns is, according to Montermini (2006), a corroborating element of the pragmatic account for word-internal anaphora acceptability, and this is why we focused on basic forms such as pronouns and zero forms. It is important to underline that Montermini’s (2006) analysis encompasses all sorts of complex words and referential expressions, hence, compared to our much narrower research, a corpus-based investigation is more feasible and allows to draw general conclusions. However, aiming to address more fine-grained issues, it would have been impossible to obtain such a control of the data if we based our investigation on corpora.

Montermini (2006) and Radimský (2015) agree that the acceptability of word-internal anaphora is explained by discourse phenomena rather than syntactic properties. We do not deny the role that pragmatic factors play in the acceptability of compound-internal pronominal anaphora. We only think that (in agreement with Ward et al., 1991) if this phenomenon is truly unacceptable, there are no contexts in which it is acceptable. Pragmatics cannot change the essence of all possible unnatural sentences making them natural. Moreover, pragmatics may be at the basis of why this phenomenon occurs, but this fact alone cannot provide an explanation for how this phenomenon occurs, and since evidence has been found in corpora, it is important to analyze the tendencies of compound-internal anaphora focusing on its form rather than on its function.

3 The study

3.1 Materials Footnote 18

The target argumental compounds were either VN, NHN or NNH. We selected items based on the frequency and usage of the compounds and the argument constituents, and the morpho-semantic transparency of the constituents. Targets selected for the experiment are listed in Table 1. There were ten of each type, five of which were combined with an overt pronoun and five of which with a null pronoun, as shown in the table.

In the selection of the target items, we aimed to find compounds that were similar in frequency, and that contained non-heads which were also similar in frequency. Both the compounds in Table 1 and the argument elements, are classified in the online vocabulary Il nuovo vocabolario di base della lingua italiana (De Mauro, 2014), as either fondamentale ‘fundamental’, di alto uso ‘high usage’, di alta disponibilità ‘high availability’, or comune ‘common’. In addition, we retrieved corpus frequencies for the compounds and their constituents from itTenTen 2016, a 4.9 billion word corpus consisting of Internet texts, available on SketchEngine (Jakubíček et al., 2013). Figure 2 shows the result. In this figure, frequencies of the compounds in the corpus are shown as green boxes in the lower part of the graph, and those of the first and second constituent within each compound type as adjacent boxes above the green boxes. Grey boxes represent the frequencies of the predicate element of the compounds, and the red boxes those of the objects. The frequency range of the compounds is 200 to 5,873, and that of the argument constituents is 56,978 to 1,362,327.

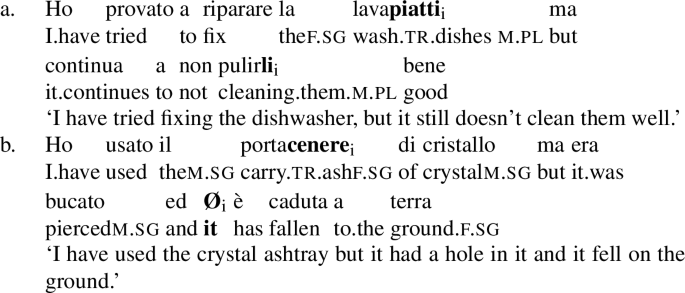

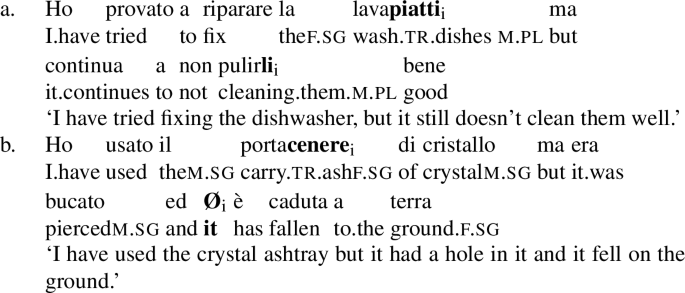

The experimental target sentences consisted of two or more clauses. Two examples are given in (27). The first clause contained one of the compounds while the last clause contained an overt pronoun (as in 27a) or a null pronoun (as in 27b) referring back to the argument element of the compound in the first clause.

-

(27)

Compounds were also matched for morpho-semantic transparency of the constituents: the referring pronoun agreed in number and gender with the argument element but not with the predicate element, as in (28a) and (28b):

-

(28)

A total of 20 distractor items were added to the experimental sentences with the purpose of masking the purpose of the experiment and to encourage the respondents to make use of all values on the acceptability scale. The distractor items contained compounds just like the target sentences. Ten of them were grammatical, and ten were not. With that, the total number of sentences presented to the respondents was 50.

3.2 Procedure

The questionnaire was carried out online through a web-hosted survey platform. At the onset, informants received information that they participated in a study on native speaker judgements and that their task would be to judge the acceptability of 50 sentences on a five-point scale (Dawes, 2008) from completely unnatural to totally natural. According to findings from empirical linguistics, Likert scales provide reliable results (Murphy & Vogel, 2008; Weskott & Fanselow, 2011; Juzek, 2015).

Italian NHN compounds are usually written as separate words, while NNH and VN compounds are written as single words. This difference in orthography presents a potential confounding factor (e.g., Marelli et al., 2015; Juhasz et al., 2005) that we wished to avoid. To do so, the stimulus sentences in the present study were not written but generated by a natural sounding online synthetic voice generator. Informants could listen to the sentences as many times as they wanted and did not have to respond within a particular time limit. They were asked to base their judgments on their intuitions, and were informed that there were no right or wrong answers. Finally, participants were told not to judge the sentences according to a prescriptive criterion but only in terms of how natural they sounded in informal, spoken contexts. After the instructions, the informants provided information about their language background, education, gender and age. The sentences were presented in a random order.

3.3 Results

The test was completed by 93 women and 47 men, all monolingual native speakers of Italian. Their age ranged from 23 to 75 years (51 years on average). All but two participants reported that they spoke at least one additional language, mostly English, but also German, Spanish and French. The majority lived in Italy at the time of their responses, but 13 reported living in another country. The highest educational level obtained reported by the participants was middle school (1), high-school (19), Bachelor’s degree (17), Master’s degree (81), Ph.D. (16), or other (6).

All respondents responded to all sentences. The total number of responses, therefore, was 7,000, 4,200 to the target sentences and 2,800 to the distractor sentences. Figure 3 shows the response distributions to the target items separately for those containing null pronouns (top row) and overt pronouns (bottom row).

The distributions in Fig. 3 indicate no clear agreement across the participants for any of the three types. However, positive responses appear to outnumber negative responses for NHN compounds and VN compounds, suggesting that the participants may have found the sentences a bit strange but did not dismiss them as unnatural. The responses to the NNH compounds on the other hand were definitely more negative.

Below, we present the results of two analyses. In the first analysis, the ratings of the target items are compared with those of the distractors. The purpose of this analysis is to establish whether the target sentences were rated comparably to the grammatical or the ungrammatical distractors. This analysis was done on the full data set. The second analysis focuses on the effect of pronoun (overt or null) on the ratings of the target types. The purpose of this analysis is to establish whether and how the ratings to the different target types were modified depending on whether the pronoun was overt or null. Since distractor sentences did not contain overt or null pronouns, this analysis was done on the target items only. For the two analyses, the ratings were replaced by the values -2 to +2. Both analyses consisted of mixed-effects regression modeling described in more detail below. The analyses were performed in R (version 4.0.2, R Core Team, 2020).

3.3.1 Analysis 1

The effects of the item categories (fixed effects) were evaluated using the ungrammatical distractors as a reference category to which the other categories were compared (so-called treatment contrast coding). The analysis also included random intercepts for the participants and for the items. The overall effect of item category was significant (likelihood ratio test: chi-square = 53.174, df = 4, p = .000). The difference between ungrammatical distractors and target sentences was significant for targets with VN compounds (EST = 0.937, SE = 0.237, df = 49.95, t = 3.961, p = 0.000) and for target sentences with NHN compounds (EST = 1.072, SE = 0.237, df = 49.95, t = 4.532, p = 0.000), but not for targets with NNH compounds (EST = 0.250, SE = 0.237, df = 49.95, t = 1.057, p = 0.300). Not surprisingly, the difference between ungrammatical and grammatical distractors was significant (EST = 2.081, SE = 0.237, df = 49.95, t = 8.798, p = 0.000). Figure 4 shows, from left to right, the model-based estimated ratings and 95% confidence intervals for the ungrammatical distractors, the three types of target sentences, and the grammatical distractors. All target sentences were rated higher than the ungrammatical distractors (notably those with VN and NHN compounds), and lower than the grammatical distractors (notably those with NNH compounds).

3.3.2 Analysis 2

The second analysis focuses on the target sentences only and the role of the pronouns in the acceptability judgements. The fixed effects in this analysis were compound type (VN, NHN or NNH), pronoun type (Null or Overt), and the interaction of these two predictors. The random effects, as in the first analysis, were random intercepts for items and for participants. As already suggested by the previous analysis, the sentences containing NNH compounds were rated lower than those containing VN and NHN compounds. The overall effect of compound was significant (likelihood ratio test: chi-square = 15.131, df = 2, p = .001). More specifically, the ratings of sentences containing NNH compounds were significantly lower than those of sentences containing VN compounds (EST =−0.687, SE = 0.199, z = −3.458, p = 0.002Footnote 19) and those containing NHN compounds (EST = 0.822, SE = 0.199, z = 4.137, p = 0.000). The difference between sentences containing VN compounds and those containing NHN compounds, on the other hand, was not significant (EST = 0.135, SE = 0.199, z = 0.679, p = 0.776).

Pronoun as an additional fixed effect did not significantly improve the model (likelihood ratio test: chi square = 1.756, df = 1, p = 0.185), and the interaction of pronoun and compound, was only marginally significant (likelihood ratio test: \(\chi^{2} = 5.267\), df = 2, p = 0.071). In sum, sentences with VN and NHN compounds were rated significantly higher than ungrammatical distractor sentences, but not sentences with NNH compounds. The predicted values (with 95% confidence intervals) for the model containing the interaction are shown in Fig. 5.

4 Discussion

The aim of this experiment was to determine whether Italian native speakers consider compound-internal pronominal reference acceptable, and the degree to which differences in compound structure and referential expressions affect their acceptability.

The results of Analysis 1 (Sect. 3.3.1) suggest that compound-internal anaphora is largely acceptable for NHN and VN compounds, but not acceptable for NNH compounds. This difference was expected, and is in line with psycholinguistic evidence. Marelli et al. (2009), for instance, investigated priming effects with NHN, NNH and VN compounds, and found that while the mental representation of left-headed and exocentric compounds is tied to both constituents, the one for NNH compounds is strongly tied to the head. This corroborates the theoretical considerations by Di Sciullo and Williams (1987) according to whom left-headed and VN compounds show a lexicalization of syntactic structures (a ‘flat representation’), while right-headed compounds represent true morphological objects (a hierarchical representation). Marelli et al. (2009) argue that the internal syntactic structure of VN compounds makes them similar to VPs, where the verb is the most important element, both syntactically and semantically. El Yagoubi et al. (2008) and Arcara et al. (2013) also found neurolinguistic evidence of a higher processing load for NNH compounds compared to NHN compounds. El Yagoubi et al. (2008) propose that this is due to the internal order of left-headed compounds reflecting the canonical Italian order of syntactic elements, thus drawing similar conclusions as Marelli et al. (2009). Interestingly, Arcara et al. (2013) show that canonical order does not fully explain compound processing, since VN and NNH compounds appear similarly affected by decompositional effect. They argue that this might be explained in terms of different grammatical properties leading to a different integration of constituents, but also in terms of their productivity in Italian, which led to expectations on their orthography (see also Arcara et al., 2014). As the authors underline (in line with Marelli & Luzzatti, 2012), compound processing often implies the interaction of parallel morphological and semantic information, and since NHN and VN compounds differ morphologically and semantically, this arguably plays a role in their processing. For these reasons, we think that limiting the analysis to argumental compounds is important to compare similar syntactic and semantic relations.

Regarding further differences between left- and right-headed compounds, Radimský (2013a,b) notices a strong correlation between orthography and the position of the head. In his investigation on “mirror compounds” (i.e., compounds that can be both left- and right-headed, e.g., radio.\(\mathit{giornale}_{\mathrm{H}}\) vs. \(\mathit{giornale}_{\mathrm{H}}\) radio ‘radio news’), he observes that right-headed compounds are consistently spelled as one word (i.e., ‘tight compounds’) while left-headed compounds are spelled as two (i.e., ‘loose compounds’). While orthography is not a reliable criterion in establishing the degree of ‘wordhood’ of a linguistic element, it may indicate linguistic intuitions by native speakers and hence, an orthographical fusion of the members might be an indicator of unity (Tollemache, 1945; Iacobini, 2010; Gaeta, 2011), reflecting “different mental word-formation models in the mind of language users” (Radimský, 2013a:48).

Therefore, we can interpret our results as reflecting the minor accessibility of the argument element of NNH compounds, and hence less tied to mental representation, which makes it less available for pronominal anaphora.

These results pose some interesting questions on how complex words are built. If we assume that lexemes are at the basis of compounding then it becomes problematic to account for our results. Lexemes are abstract units of lexical organization and lack grammatical properties (e.g., definiteness): hence they cannot have a referential status. Montermini (2010) argues that in some cases (e.g., argumental compounds), concrete word forms appear to be at the basis of compound formation. However, he also mentions neoclassical compounds as a particular type on the basis of their elements, which are not independent syntactic elements, e.g., cardiologo ‘cardiologist’: building elements such as cardio- would represent a suppletive form of the autonomous cuore ‘heart’ (in agreement with Guevara & Scalise, 2009), possessing a [+bound] feature in the lexical representation (Corbin, 1992). Montermini (2010) states that neoclassical compounds are sometimes based on different rules than those of ‘native’ compounds, and from our results, it appears that the structure, rather than the mere semantic transparency of the elements (we used only semantically transparent elements in our target) plays a greater role.

These considerations are highly interrelated with those on the flat and hierarchical representations for NHN and NNH compounds respectively, and possibly with mirror compounds. We argue that examples such as \(\mathit{lavaggio}_{\mathrm{H}}\) auto ‘car wash’ or \(\mathit{noleggio}_{\mathrm{H}}\) video ‘video rental’ indicate a type of activity or event (expressed by the deverbal noun) specialized by its argument (i.e., ‘a kind of wash/rental specific for cars/video’), while the NNH counterpart (in this cases auto.\(\mathit{lavaggio}_{\mathrm{H}}\), video.\(\mathit{noleggio}_{\mathrm{H}}\)) preferably indicates an entity (i.e., ‘the place one goes to have the car washed or the videos rented’). This semantic specialization may be the cause of an increased lexicalization, which would further increase the opacity of the argument element: the metonymic shift would hence be systematic thanks to the structural feature of the position of the head. However, as already noted by Ricca (2015) regarding VN compounds, it is difficult to determine whether this semantic shift has to be considered as the result of word-formation rules or if it reflects a more general cross-linguistic polysemy involving action nouns and the place where the activity is performed.Footnote 20 Additional investigations are needed in order to establish whether this phenomenon represents a clear measurable tendency in the language, or rather whether these examples are merely isolated instances and not markers of a greater tendency.

The very low degree of acceptance of pronominal anaphora in NNH compounds may be explained in terms of speakers’ world knowledge. As Montermini (2006) states, a predictable relationship between the referent and a derivative would represent a facilitating condition for in-word anaphora, and he observes that this would explain why geographical nouns and adjectives are often available for in-word anaphora even when not morphologically transparent:

-

(29)

The ethnic nouns in (29) in Italian are not equally transparent (francese ‘French’ - Francia ‘France’ vs. tedesco ‘German’ - Germania ‘Germany‘), yet both of them accept in-word anaphora, something that is explained by Montermini (2006) precisely in terms of the degree of predictability between the referent and the derived word, i.e., speakers’ world knowledge (see Bresnan, 1971, who argues that subwords are interpreted as antecedents because they are inferred rather than grammatically assigned). However, and this is why carefully designed experiments are crucial, it is not clear what kinds of inferences and inferred antecedents are acceptable or not, and further research is needed to investigate the role of other possible aspects (e.g., word length, familiarity with referents, etc.).

Something that was pointed out by an anonymous reviewer is the question of whether it is possible at all to disentangle pragmatic factors from purely grammatical ones. In this respect, our test cannot solve all complex issues regarding the influence of pragmatics. However, all the items in the test were out-of-context sentences and consisted of a very similar structure. Yet, a preference for syntactic strategies over others is clear from the results. This would support our assumption that right-headed compounds are not open to compound-internal anaphora, possibly due to a difference in their qualitative nature.

Our results also show that sentences with overt pronouns as referential expressions are on average more acceptable than those with null pronouns. One notable exception is the one represented by NHN compounds. In this case, sentences with null pronouns are more accepted than those with overt pronouns. The interplay between information structure and syntactic role is not clear. Italian is a null-subject language, and null forms refer to subjects, while overt pronouns refer to direct objects. An explanation for our results may be related to the influence of information structure. Syntactic functions are tightly related to informative functions and a correlation between subjects and topics is well known (Lambrecht, 1994).Footnote 21 However, future studies may establish why this is the case only for NHN compounds and not for VN compounds. This finding might be linked to the one by Arcara et al. (2013) on the similar processing of VN and NNH compounds: NHN compounds might possess a more syntactic reading, while the higher lexical cohesion of VN compounds may reflect differences in the autonomy, and hence referential capacity, of the argument element, and this might influence information structure as well. To be able to shed light on these issues, further work is needed on Italian subject overt pronouns or on languages that allow deletion of both subject and object pronouns.

An anonymous reviewer also suggested further analyses on semantic transparency, since it may play a role in compound-internal anaphora (see Günther et al., 2020). As we discussed, argument structure has been defined to allow for a direct interpretation because of its semantic predictability (Bauer et al., 2013); however we agree that a fine-grained analysis on semantic transparency investigating the constraints on compound-internal anaphora would surely give interesting results, and thus recommend it for future research.

Furthermore, it would be interesting to investigate whether sociolinguistic factors may influence compound-internal pronominal reference. Diatopic and diastratic considerations were not the main focus of our study, but it may be fruitful to investigate this issue further.

Our results allowed us to shed light on a phenomenon that is still debated in linguistic theory. Even if we could establish the non-acceptability of compound-internal pronominal reference because this is not rated as high as grammatical distractors, we still have to account for the different degrees of acceptability according to compound structure. Moreover, if we were tempted to conclude that these sentences are judged acceptable only due to ‘pragmatic inference’, we would also need to explain why pragmatic inference does not succeed in all cases to the same extent.

Our results show that a closer look at experimental data is crucial, not only for well-established phenomena but especially for phenomena that appear to be on the edge of acceptability but that nevertheless show tendencies and preferences that need to be taken into account. Theory must necessarily draw on experimental evidence, and in turn, experiments need to be carefully designed in order to provide nuanced data that allow theoretical considerations to account for them. To answer our research questions, an acceptability judgment task not only proved to be appropriate to verify the acceptability of the phenomenon but also to grasp subtle variations on this phenomenon concerning the structure of compounds and the quality of referential expressions.

5 Conclusion

Our findings suggest that compound-internal anaphora is largely accepted with NHN and VN compounds in Italian. The argument element of NNH compounds appears to be impenetrable to pronominal anaphora. Moreover, a difference in referential expression was suggested, with NHN allowing null subject anaphora more than all the other complex words. Although previous findings indicated that NNH compounds are processed differently from NHN compounds, less clear results have been shown in the literature regarding NN compounds compared to VN compounds. The results support theoretical models suggesting a qualitative difference of compounding structures based on the position of the head, and show that the quality of the referential expression can facilitate or inhibit compound-internal anaphora. Future research may focus on the impact of a previously given context in the acceptability of these instances. Regardless, our results point to the need for tighter integration of experimental methods to theoretical considerations and corpus-based research to investigate the syntactic properties of compounds.

Data Availability

Responses are available on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/wznm3/?view_only=d23e89ce480b4e80a69667af89aafec9.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Subordinate compounds are compounds showing a syntactic dependency between the elements, i.e. a head-complement relation.

Non-deverbal argumental compounds are rare in Italian, and non-derived event nouns do not appear to form compounds with their arguments. Therefore, an argumental structure constituted by a transitive verb and its direct object appears to be prototypical in Italian verbal-nexus compounds (Radimský, 2015). Moreover, as Radimský (2015) shows, a significant number of heads of these compounds are not derived from verbs.

Unlike Baroni et al. (2009a), we did not include compounds where the non-head is the subject of an unaccusative verb, e.g., caduta massi ‘rockfall’.

For instance, the relation between verbal and nominal constituents has been shown to play a major role in the position of the head in Chinese compounds (Ceccagno & Basciano, 2007).

For a thorough analysis on the notion of “head” in compounds see Scalise and Fábregas (2010).

Except for Romanian (Grossmann, 2012).

However, Ricca (2005) also shows oblique arguments, e.g. salva incendi boschivi ‘protect (from) wild-fires’ or proteggi-vento ‘windshield’.

Only left-headed argumental compounds are normally taken into account. To the best of our knowledge, there is no systematic overview of Italian right-headed argumental compounds.

Cf. Radimský (2018), however, who attests their presence in French, even though without the regularity present in Italian.

In these studies, the argumental relation between the elements is taken as evidence of a syntactic nature. However, Bisetto (2004) considers these structures as a peculiar kind of compound.

See also Masini and Scalise’s (2012) example: ?Il lavoro consiste in una raccolta-fondi e dati, lit. ‘The job consists of collection-funds and data’.

Radimský (2015) emphasizes that the acceptability of (6c) might be due to the interpretation of the objects as two coordinated arguments, i.e. il trasporto [passeggeri e merci] ‘[passengers- and goods] transportation’, hence becoming a case of insertion and not of head deletion.

In his analysis, “complex words” should not be considered from a morphological point of view only: his investigation touches on many different issues, ranging from morphology to information structure and semantics.

He defines this phenomenon as “outbound anaphora”, which is what we investigate in our study. We did not analyze inbound anaphora (i.e., where the referential expression becomes a sub-part of a word) as these two phenomena are structurally different (Haspelmath, 2011).

He also affirms that the antecedent and the anaphoric pronoun need to be in two different but adjacent clauses, something that has been taken into consideration in the design of our target sentences.

Semantics plays a decisive role also in the analyses by Tic Doloureux (1971), who argues that the relation between antecedent and pronoun must be semantic in nature, often defined by a part-whole correspondence.

All the stimuli, the responses and the performed analyses are available on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/wznm3/?view_only=d23e89ce480b4e80a69667af89aafec9.

p-values corrected for multiple comparisons using the single-step method.

These considerations can be related to observations made by Arcodia et al. (2010) on coordinative compounds. According to these authors, an attributive relation, rather than true coordination, would arise between the right and the left element. These observations are shared by Scalise and Fábregas (2010) and Radimský (2015).

This appears in line with Fábregas (2012), who notices that in-word anaphora in Spanish is facilitated with subject pronouns and less acceptable with object pronouns.

References

Ackema, P., & Neeleman, Ad. (2004). Beyond morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Allen, M. (1978). Morphological investigations. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut.

Altakhaineh, A. R. M. (2019). A cross-linguistic perspective on the Right-Hand Head Rule: The rule and the exceptions. Linguistics Vanguard, 5(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2018-0033.

Arcara, G., Marelli, M., Buodo, G., & Mondini, S. (2013). Compound headedness in the mental lexicon: An event-related potential study. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 31(1–2), 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643294.2013.847076.

Arcara, G., Semenza, C., & Bambini, V. (2014). Word structure and decomposition effects in reading. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 31(1–2), 184–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643294.2014.903915.

Arcodia, G. F., Grandi, N., & Montermini, F. (2009). Hierarchical NN compounds in a cross-linguistic perspective. Italian Journal of Linguistics, 22(1), 11–33.

Arcodia, F. G., Grandi, N., & Wälchli, B. (2010). Coordination in compounding. In S. Scalise & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-Disciplinary Issues in Compounding (pp. 177–197). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.311.15arc.

Baroni, M., Guevara, E., & Pirrelli, V. (2009a). Sulla tipologia dei composti N + N in italiano: principi categoriali ed evidenza distribuzionale a confronto. In R. Benatti, G. Ferrari, & M. Mosca (Eds.), Linguistica e Modelli Tecnologici di Ricerca: Atti del 40esimo Congresso Internazionale di Studi della Società di Linguistica Italiana (SLI) (pp. 73–95). Roma: Bulzoni.

Baroni, M., Guevara, E., & Zamparelli, R. (2009b). The dual nature of deverbal nominal constructions: Evidence from acceptability ratings and corpus analysis. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 5(1), 27–60. https://doi.org/10.1515/CLLT.2009.002.

Bauer, L. (2001). Compounding. In M. Haspelmath, E. König, W. Oesterreicher, & W. Raible (Eds.), Language Universals and Language Typology (pp. 695–707). Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Bauer, L. (2009). Typology of compounds. In R. Lieber & P. Štekauer (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Compounding (pp. 343–356). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199695720.013.0017.

Bauer, L. (2010). The typology of exocentric compounds. In S. Scalise & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-disciplinary Issues in Compounding (pp. 167–175). Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.311.14bau.

Bauer, L. (2013). Compounds: semantic considerations. In L. Bauer, R. Lieber, & I. Plag (Eds.), The Oxford Reference Guide to English Morphology (pp. 463–490). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198747062.003.0020.

Bauer, L., Lieber, R., & Plag, I. (2013). The Oxford reference guide to English morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198747062.001.0001.

Bisetto, A. (1994). Italian compounds of the accendigas type: A case of endocentric formations? University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics, 4(2), 1–10.

Bisetto, A. (1999). Note sui composti VN dell’italiano. In P. Benincà, A. Mioni, & L. Vanelli (Eds.), Fonologia e Morfologia dell’Italiano e dei Dialetti d’Italia. Atti del XXXI Congresso della Società di Linguistica Italiana (pp. 505–538). Rome: Bulzoni.

Bisetto, A. (2004). Composizione con elementi italiani. In M. Grossmann, F. Rainer, & P. M. Bertinetto (Eds.), La Formazione delle Parole in Italiano, (pp. 33–50). Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Bisetto, A. (2006). The Italian suffix -tore. Lingue e Linguaggio, 2, 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1418/23146.

Bisetto, A. (2010). Recursiveness and Italian compounds. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics, 7, 14–35.

Bisetto, A. (2015). Do Romance languages have phrasal compounds? A look at Italian. STUF - Language Typology and Universals, 68(3), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1515/stuf-2015-0018.

Bisetto, A., & Melloni, C. (2008). Parasynthetic compounding. Lingue e Linguaggio, 7(2), 233–260.

Bisetto, A., & Scalise, S. (1999). Compounding: Morphology and/or syntax? In L. Mereu (Ed.), Boundaries of Morphology and Syntax (pp. 31–48). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Booij, G. (2010). Compound construction: Schemas or analogy? A construction morphology perspective. In S. Scalise & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-disciplinary Issues in Compounding (pp. 93–108). Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.311.09boo.

Bresnan, J. (1971). A note on the notion ‘identity of sense anaphora’. Linguistic Inquiry, 2, 589–597.

Browne, W. (1974). On the topology of anaphoric peninsulas. Linguistic Inquiry, 5, 612–620.

Ceccagno, A., & Basciano, B. (2007). Compound headedness in Chinese: An analysis of neologisms. Morphology, 17(2), 207–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-008-9119-0.

Corbin, D. (1992). Hypothèses sur les frontières de la composition nominale. Cahiers de Grammaire, 17, 27–55.

Corum, C. (1973). Anaphoric peninsulas. Chicago Linguistic Society, 9, 89–97.

Dash, N. S., & Ramamoorthy, L. (2019). Issues in text corpus generation. In Utility and Application of Language Corpora, Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1801-6.

Dawes, J. (2008). Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? International Journal of Market Research, 50(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530805000106.

De Mauro, T. (2014). Il nuovo De Mauro online. Internazionale. https://dizionario.internazionale.it/.

Delfitto, D., & Paradisi, P. (2009a). Prepositionless genitive and N + N compounding in Old French and Italian. In D. Torck & L. Wetzels (Eds.), Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2006. Selected papers from ‘Going Romance’ (pp. 53–72). Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.303.04del.

Delfitto, D., & Paradisi, P. (2009b). Towards a diachronic theory of genitive assignment in Romance. In P. Crisma & G. Longobardi (Eds.), Historical Syntax and Linguistic Theory (pp. 292–310). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199560547.003.0017.

Di Sciullo, A. M., & Williams, E. (1987). On the definition of word. Cambridge: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226700012184.

Dressler, W. (1987). Morphological islands: Constraint or preference? In R. Steele & T. Threadgold (Eds.), Language Topics: Essays in Honour of Michael Halliday (H) (pp. 71–79). Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.lt2.51dre.

El Yagoubi, R., Chiarelli, V., Mondini, S., Perrone, G., Danieli, M., & Semenza, C. (2008). Neural correlates of Italian nominal compounds and potential impact of headedness effect: An ERP study. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 25, 559–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643290801900941.

Fábregas, A. (2012). Islas y penínsulas anafóricas: gramática y pragmática. Estudios Filológicos, 50, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0071-17132012000200002.

Gaeta, L. (2010). Synthetic compounds: With special reference to German. In S. Scalise & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-Disciplinary Issues in Compounding (pp. 219–235). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.311.17gae.

Gaeta, L. (2011). Univerbazione. In Enciclopedia dell’Italiano online. Treccani, https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/univerbazione_%28Enciclopediadell%27Italiano%29/.

Gaeta, L., & Ricca, D. (2009). Composita solvantur: Compounds as lexical units or morphological objects? Italian Journal of Linguistics, 21(1), 35–70.

Gather, A. (2001). Romanische Verb-Nomen-Komposita: Wortbildung zwischen Lexikon, Morphologie und Syntax, Tübingen: Narr.

Grandi, N. (2006). Considerazioni sulla definizione e la classificazione dei composti. Annali dell’Università di Ferrara - Lettere, 1, 31–52. https://doi.org/10.15160/1826-803X/77.

Grossmann, M. (2012). Romanian compounds. Probus, 24(1), 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1515/probus-2012-0007.

Guerrero Medina, P. (2018). Towards a comprehensive account of English -er deverbal synthetic compounds in functional discourse grammar. Word Structure, 11(1), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.3366/word.2018.0114.

Guevara, E., & Scalise, S. (2009). Searching for universals in compounding. In S. Scalise & A. Bisetto (Eds.), Universals of Language today (pp. 101–128). Amsterdam: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8825-4_6.

Günther, F., Marelli, M., & Bölte, J. (2020). Semantic transparency effects in German compounds: A large dataset and multiple-task investigation. Behavior Research Methods, 52(3), 1208–1224. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01311-4.

Haspelmath, M. (2002). Understanding morphology. London: Hodder.

Haspelmath, M. (2011). The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax. Folia Linguistica, 45(1), 31–80. https://doi.org/10.1515/flin.2011.002.

Iacobini, C. (2004). Composizione con elementi neoclassici. In M. Grossmann, F. Rainer, & P. M. Bertinetto (Eds.), La Formazione delle Parole in Italiano, (pp. 69–96). Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Iacobini, C. (2010). Composizione. In Enciclopedia dell’Italiano online. Treccani, https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/composizione_%28Enciclopedia-dell%27Italiano%29/.

Jakubíček, M., Kilgarriff, A., Kovář, V., Rychlý, P., & Suchomel, V. (2013). The TenTen corpus family. In International Corpus Linguistics Conference CL (pp. 125–127). Lancaster: Lancaster University.

Juhasz, B., Inhoff, A., & Rayner, K. (2005). The role of interword spaces in the processing of English compound words. Language and cognitive processes, 20(1–2), 291–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690960444000133.

Juzek, T. (2015). Acceptability judgement tasks and grammatical theory. Dissertation, University of Oxford.

Lakoff, G., & Ross, J. R. (1972). A note on anaphoric islands and causatives. Linguistic Inquiry, 3(1), 121–125.

Lambrecht, K. (1994). Information structure and sentence form: Topics, focus, and the mental representations of discourse referents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511620607.

Lieber, R. (1992). Deconstructing morphology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lieber, R. (1994). Root compounds and synthetic compounds. In R. Asher & J. Simpson (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (pp. 3607–3610). Oxford: Pergamon.

Lieber, R. (2009) IE, Germanic: English. In R. Lieber, & P. Štekauer (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Compounding (pp. 357–369). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199695720.013.0018.

Lieber, R. (2010). Introducing morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808845.

Lieber, R., & Scalise, S. (2006). The lexical integrity hypothesis in a new theoretical universe. Lingue e Linguaggio, 1, 7–32.

Mackenzie, J. L. (1990). First argument nominalizations in a functional grammar of English. Linguistica Antverpiensia, 24, 119–127.

Marchand, H. (1969). The categories and types of present-day English word formation: A synchronic-diachronic approach. Munich: Beck. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3841(71)90076-3.

Marelli, M., Crepaldi, D., & Luzzatti, C. (2009). Head position and the mental representation of Italian nominal compounds: A constituent priming study in Italian. The Mental Lexicon, 4, 430–455. https://doi.org/10.1075/ml.4.3.05mar.

Marelli, M., & Luzzatti, C. (2012). Frequency effects in the processing of Italian nominal compounds: Modulation of headedness and semantic transparency. Journal of Memory and Language, 66(4), 644–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.01.003.

Marelli, M., Dinu, G., Zamparelli, R., & Baroni, R. (2015). Picking buttercups and eating butter cups: Spelling alternations, semantic relatedness, and their consequences for compound processing. Applied Psycholinguistics, 36(6), 1421–1439. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716414000332.

Masini, F., & Scalise, S. (2012). Italian compounds. Probus, 24(1), 61–91. https://doi.org/10.1515/probus-2012-0004.

Melloni, C. (2020). Subordinate and synthetic compounds in morphology. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics (pp. 1–40). London: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.562.

Melloni, C., & Bisetto, A. (2010). Parasynthetic compounds: Data and theory. In S. Scalise & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-Disciplinary Issues in Compounding (pp. 199–218). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.311.16mel.

Micheli, M. S. (2016). Limiti e potenzialità dell‘uso di dati empirici in lessicografia: il caso del plurale delle parole composte. RiCognizioni, 3(6), 15–33. https://doi.org/10.13135/2384-8987/1833.

Montermini, F. (2006). A new look on word-internal anaphora on the basis of Italian data. Lingue e Linguaggio, 1, 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1418/22016.

Montermini, F. (2010). Units in compounding. In S. Scalise & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-Disciplinary Issues in Compounding (pp. 77–92). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.311.08mon.

Murphy, B., & Vogel, C. (2008). An empirical comparison of measurement scales for judgements of linguistic acceptability. Tübingen. Poster presented at the Linguistic Evidence 2008 conference.

Myers, J. (2017). Acceptability Judgments. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.333.

Postal, P. (1969). Anaphoric Islands. Chicago Linguistic Society, 5, 205–239.

R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

Radimský, J. (2006). Les composés italiens actuels. Paris: Cellule de recherche en linguistique.

Radimský, J. (2013a). Position of the head in Italian N + N compounds: The case of “mirror compounds”. Linguistica Pragensia, 1, 41–52.

Radimský, J. (2013b). Tight N − N compounds in the Italian la Repubblica corpus. In J. Baptista & M. Monteleone (Eds.), Actes du 32ème Colloque International sur le Lexique et la Grammaire (10-14 septembre 2013, Faro, Portugal), (pp. 291–301). Faro.

Radimský, J. (2015). Noun+Noun compounds in Italian: A corpus-based study. České Budějovice: Jihočeská univerzita. Edice Epistémé.

Radimský, J. (2018). Does French have verbal-nexus Noun+Noun compounds? Linguisticae Investigationes, 41(2), 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1075/li.00020.rad.

Ricca, D. (2005). Al limite tra sintassi e morfologia: I composti aggettivali V-N nell’italiano contemporaneo. In M. Grossmann & A. Thornton (Eds.), La Formazione delle Parole: Atti del XXVII Congresso Internazionale di Studi della Società di Linguistica Italiana (SLI): L’Aquila, 25-27 Settembre 2003 (pp. 465–486). Roma: Bulzoni. https://doi.org/10.1400/57304.

Ricca, D. (2010). Corpus data and theoretical implications: With special reference to Italian V-N compounds. In S. Scalise & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross–disciplinary Issues in Compounding (pp. 167–175). Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.311.18ric.

Ricca, D. (2015). Verb-Noun compounds in Romance. In P. Müller, I. Ohnheiser, S. Olsen, & F. Rainer (Eds.), Word-Formation: An International Handbook of the Languages of Europe (pp. 688–707). Berlin: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110246254-041.

Roeper, T., & Siegel, M. (1978). A lexical transformation for verbal compounds. Linguistic Inquiry, 9, 199–260.

Scalise, S. (1986). Generative morphology. Dordrecht: Foris. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110877328.

Scalise, S. (1990). In Morfologia e lessico, Bologna: Il Mulino.

Scalise, S. (1992a). Compounding in Italian. Rivista di Linguistica, 4, 175–199.

Scalise, S. (1992b). The morphology of compounding. Special Issue of «Rivista di Linguistica», 4(1).

Scalise, S. (1994). Morfologia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Scalise, S., & Bisetto, A. (2011). The classification of compounds. In R. Lieber & P. Štekauer (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Compounding (pp. 34–53). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199695720.013.0003.

Scalise, S., Bisetto, A., & Guevara, E. (2005). Selection in compounding and derivation. In W. Dressler, D. Kastovsky, O. Pfeiffer, & F. Rainer (Eds.), Morphology and its Demarcations (pp. 133–150). Amsterdam/Philadephia: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.264.09sca.

Scalise, S., & Fábregas, A. (2010). The head in compounding. In S. Scalise & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-Disciplinary Issues in Compounding (pp. 109–126). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.311.10sca.

Scalise, S., Fábregas, A., & Forza, F. (2009). Exocentricity in compounding. Gengo Kenkyu (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan), 135, 49–84.

Scalise, S., & Guevara, E. (2006). Exocentric compounding in a typological framework. Lingue e Linguaggio, 2, 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1418/23143.

Schwarze, C. (2005). Grammatical and para-grammatical word formation. Lingue e Linguaggio, 2, 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1418/20718.

Selkirk, E. (1982). The syntax of words. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Tekavčić, P. (1972). In Grammatica storica dell’italiano. III: Lessico, Bologna: Il Mulino.

Tic Doloureux (1971). A note on one’s privates. In A. Zwicky, P. Salus, R. Binnick, & A. Vanek (Eds.), Studies out in Left Field (pp. 45–51). Edmonton: Linguistic Research. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.63.15dou. [Tic Doloureux is a pseudoymn of Stephen Anderson].

Tollemache, F. (1945). Le parole composte nella lingua italiana. Rome Rores.

Varela, S. (1990). Composición nominal y estructura tematica. Revista Española de Lingüística, 1, 56–81.

Ward, G., Sproat, R., & McKoon, G. (1991). A pragmatic analysis of so-called anaphoric islands. Language, 67(3). https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1991.0003.

Weskott, T., & Fanselow, G. (2011). On the informativity of different measures of linguistic acceptability. Language, 87(2). https://doi.org/10.1353/LAN.2011.0041.

Zuffi, S. (1981). The nominal composition in Italian. Topics in generative morphology. Journal of Italian Linguistics, 2, 1–54.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very much indebted to Roberta Colonna Dahlman, Verner Egerland, Maria Silvia Micheli and Jan Radimský for inspiration, patient guidance and useful critiques of this work. We thank Jeroen van de Weijer for many revisions, and the anonymous reviewers for careful reading and insightful comments and suggestions. We also thank all our experimental subjects.

A preliminary version of this study was presented on September 2020 at “Grammatikseminariet” at Lund University Centre for Languages and Literature. We received many precious insights from the participants. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge Lund University Humanities Lab.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I. Lami conceived the study, planned the experiment and collected the data. J. van de Weijer reviewed the experiment and performed data analysis. Both authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Consent to participate

Prior to data collection participants agreed to the terms and conditions.

Consent to publication

Prior to data collection participants agree to the publication of results.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lami, I., van de Weijer, J. Compound-internal anaphora: evidence from acceptability judgements on Italian argumental compounds. Morphology 32, 359–388 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-022-09398-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-022-09398-w