Abstract

Adjectives whose stems consist of two elements (or binomial adjectives) are becoming increasingly productive in colloquial Japanese. Unlike the stems of conventional adjectives, the stems of numerous, but not all, innovative binomial adjectives can have two distinct inflectional behaviors (e.g., daru-omo-{i/na} ‘be languid and heavy’, aza-kawai-i/aza-kawa-na ‘be shrewd and cute’) and have different syntactic properties depending on the suffix. Within the framework of Relational Morphology, the current study proposes that two independently established word-formation rules, represented as “sister schemas,” account for the apparent derivational gaps in these adjectives and their difference in productivity. I-forms are crucially based on particular subschemas, such as X-kawai-i ‘be X and cute’ and kuso-Y-i ‘be very Y’, and are not fully productive, whereas na-forms have detailed morphophonological constraints and are notably productive. The two suffixes are available only if an adjective stem meets the structural and semantic requirements of both schemas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Japanese has two types of adjectives: i- and na-adjectives, also called keiyōshi ‘describing word’ and keiyōdōshi ‘describing verb’ in the grammatical tradition, or “verbal” and “nominal adjectives” in English. The stems of i-adjectives and na-adjectives have different properties: the former cannot be independent elements, whereas the latter are nominal elements. Both types of adjectives syntactically behave like verbs. Unlike adjectives in many languages, they inflect for tense even in their attributive uses, as in (1), where i-adjectives end with the suffix -i (nonpast) or -katta (past), whereas na-adjectives end with the adnominal copula -na (nonpast) or -datta (past) (Miyagawa, 1987; Murasugi, 1990; Baker, 2003).

-

(1)

The Japanese lexicon consists of four strata—the native, Sino-Japanese, (non-Chinese) loaned, and ideophonic strata—which are subject to different sets of phonological constraints (Itô & Mester, 1999). The two adjective categories have different morphological and etymological characteristics, which Nishiyama (1999:204) describes as follows: “[na-adjectives] are [Sino-Japanese or non-Chinese] loan words or polymorphemic, while [i-adjectives] are native and monomorphemic.” In fact, most conventional adjectives can only take either -i/-katta or -na/-datta, as in (2a, b). According to the list of 3,415 adjectives from the Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese, only six adjective stems, all native, are compatible with both -i and -na, as in (2c).

-

(2)

Nishiyama’s generalization, however, does not apply to innovative binomial adjectives (henceforth, IBAs). IBA stems consist of two morphemes (adjectives, verbs, nouns, ideophones, or affixes) from all four lexical strata, as in (3).

-

(3)

kimo-kawai-i ‘be weird but cute’ (native + native)Footnote 1

yan-dere-na ‘be sick and slovenly, have an unhealthy romantic obsession’ (native + ideophonic)

kyasya-kawa-na ‘be slightly built and cute’ (Sino-Japanese + native)

bari-emo-i ‘be very emotional’ (native + loaned)

IBAs are highly colloquial and are becoming increasingly productive, especially among young speakers. Many of these adjectives have both i- and na-forms, as in (4).

-

(4)

aza-{kawai-i/kawa-na} ‘be shrewd and cute’

ero-{kawai-i/kawa-na} ‘be erotic and cute’

kimo-{kawai-i/kawa-na} ‘be weird but cute’

uza-{kawai-i/kawa-na} ‘be annoying but cute’

daru-omo-{i/na} ‘be languid and heavy’

oni-mazu-{i/na} ‘taste terribly bad’

oni-uma-{i/na} ‘be terribly yummy’

huk-karu-{i/na} ‘be light-footed’

The difference between i-IBAs and na-IBAs goes beyond suffix selection. Only na-IBAs often require truncation to get a four-mora stem, as in aza-kawa-na ‘be shrewd and cute’ (cf. azato-kawai-{i/*na} (5 moras)) and ero-kawa-na ‘be sexy and cute’ (cf. ero-kawai-{i/*na} (5 moras)). Even IBAs that do not involve truncation have different accent patterns in their i- and na-forms. Japanese is a pitch accent language which distinguishes high- and low-pitched moras (Labrune, 2012; Kubozono, 2015). In Tokyo Japanese, an accent nucleus is realized as an abrupt pitch fall, as in áme (high-low) ‘rain’. Japanese also has unaccented words which retain high pitch until their end, as in ame-ga0 (low-high-high) ‘candy-nom’. There is a stark prosodic contrast between the two IBA forms: i-forms are accented (e.g., daru-omó-i ‘be languid and heavy’, oni-mazú-i ‘taste terribly bad’), whereas na-forms are unaccented (e.g., daru-omo-na0, oni-mazu-na0).

It should be noted that Japanese also has more than 300 conventional complex adjectives that typically consist of two native morphemes (Yumoto, 1990; Taniwaki, 1997). The majority of these adjectives only have either i-forms (e.g., ama-zuppa-{i/*na} ‘be sweet and sour’, horo-niga-{i/*na} ‘be slightly bitter’, ma-atarasi-{i/*na} ‘be brand-new’), in accordance with the stratal part of Nishiyama’s generalization (i.e., -i for native adjectives), or na-forms (e.g., ko-iki-{*i/na} ‘be somehow stylish’, mas-sao-{*i/na} ‘be deep blue’, oo-ama-{*i/na} ‘be very indulgent’), in accordance with the morphological part of the same generalization (i.e., -na for polymorphemic adjectives). A large number of conventional complex adjectives involve noun incorporation (e.g., kuti-beta-na ‘be poor at expressing oneself (mouth-poor-na.npst)’, ne-zuyo-i ‘be deep-rooted (root-strong-i.npst)’, oku-buka-i ‘be deep (depths-deep-i.npst)’), an unproductive compounding process in IBAs (see Sect. 3.1). IBAs are distinguished from these conventional adjectives in that they have innovative, playful tones and are not registered in most dictionaries (yet).

In this paper, we demonstrate that the highly systematic lexicon of IBAs is crucially based on the increasing productivity of two morphological rules (or schemas)—one for i-IBAs and the other for na-IBAs—and the formal and functional specifications of these rules account for the non-uniform behavior the two types of IBAs exhibit. The coexistence of i-IBAs and na-IBAs in colloquial Japanese can be considered an example of competition (aka rivalry). Competition is a situation in which “speakers routinely have to make a choice between alternative ways of realizing a certain concept” (Gardani et al., 2019:4). For example, English has two competing forms for the comparative (e.g., greater vs. more beautiful). The type of competition observed in IBAs involves what Fradin (2019) calls “doublets.” He defines doublets as “forms derived from the same base which exhibit distinct exponents although they have the same meaning” (Fradin, 2019:71).Footnote 2 His examples of doublets in French nominalizations include rançonn-age and rançonne-ment, both meaning ‘ransoming’ (Fradin, 2019:74; see also Plag, 2000; Bonami & Strnadová, 2019). Likewise, Japanese has several agentive suffixes, which can follow the same verbal nouns (e.g., unten-syu ‘driver (as opposed to a passenger)’ vs. unten-sya ‘driver (as opposed to a pedestrian)’). The two types of IBAs exhibit a similar situation in which the same pair of words often form both i- and na-IBAs whose semantic/pragmatic difference is quite subtle (e.g., aza-kawai-i and aza-kawa-na ‘be shrewd and cute’), with the na-forms sounding slightly more slang-like. Employing Relational Morphology (Jackendoff & Audring, 2020), this paper proposes a theoretical treatment of morphological competition, with special attention to these IBA doublets.

The organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 introduces Relational Morphology as a theoretical framework for analyzing morphological networks. Section 3 describes the semantic and morphophonological properties of i- and na-IBAs and discusses their apparent derivational gaps. Section 4 delves into these gaps, elaborating on two output-oriented morphological rules that are motivated independently. Section 5 concludes this paper.

2 Relational Morphology

The current paper adopts Jackendoff and Audring’s (2020) Relational Morphology (henceforth, RM) as a theoretical framework for analyzing morphological competition. RM is founded on Jackendoff’s (2002) “tripartite parallel architecture” view of human language. This theory considers words and word-level patterns as combinations of semantic, syntactic, and phonological information. For example, the English noun pacifism is represented as in (5).

-

(5)

Semantics:

[PACIFISM]1

Morphosyntax:

[N — aff2]1

Phonology:

/pæsɪf ɪzəm2/1

The correspondences between the three levels are specified by “interface links,” which are represented by coindexes. Coindex 1 shows that the whole phonological string /pæsɪfɪzəm/ is a noun meaning ‘pacifism’. While coindex 2 indicates that /ɪzəm/ is a suffix, the /pæsɪf/ part does not have a coindex because it does not belong to any syntactic category.

RM also employs “relational links” to capture the relationships between words. The representations in (6) show the paradigmatic relationship between pacifism and pacifist (Booij, 2010; Štekauer, 2014; Stump, 2019). RM calls this type of horizontal relation “sister relation,” in which two words “share structure, but neither contains all of the other” (Jackendoff & Audring, 2020:106). The newly added coindex 3 indicates that the two nouns share the /pæsɪf/ part.

-

(6)

Semantics:

a.

PACFISM1

b.

[ADHERENT (PACIFISM1)]4

Morphosyntax:

[N — aff2]1

[N — aff5]4

Phonology:

/pæsɪf3 ɪzəm2/1

/pæsɪf3 ɪst5/4

Crucially, relational links are further utilized for clarifying the relationships between morphological schemas. Variable coindexes α and β in (7) indicate that individual ism- and ist-words, which constitute a derivational paradigm, instantiate these “sister schemas.”

-

(7)

Semantics:

a.

IDEOLOGYβ

b.

[ADHERENT (IDEOLOGYβ)]x

Morphosyntax:

[N — aff2]β

[N — aff5]x

Phonology:

/\(\dots _{\alpha}\) ɪzəm2/β

/\(\dots _{\alpha}\) ɪst5/x

(adapted from Jackendoff & Audring, 2020:108)

RM works as an effective framework for discussing the morphological competition in Japanese IBAs, which requires all semantic, syntactic, and phonological scrutinies. In the next section, as a first step to these scrutinies, we describe the formal and functional properties of IBAs and their apparent derivational gaps.

3 Derivational gaps in IBAs

The two types of IBAs often form doublets (e.g., aza-kawai-i and aza-kawa-na ‘be shrewd and cute’). However, they also exhibit systematic derivational gaps (e.g., saku-uma-na ‘be crunchy and therefore yummy’ but *saku-uma-i). In this section, we discuss semantic and structural gaps in the derivational network of IBAs.

As no comprehensive description is available for IBAs, we started with the compilation of word lists. We collected IBAs from approximately 400 undergraduate students in Nagoya and from the internet. We showed the students several examples of IBAs, such as (3), and asked them to list as many similar forms as possible with example phrases or sentences. As for the semi-random internet search, we searched Google for possible na-IBA counterparts to existing i-IBAs and vice versa. We also searched for new IBA forms we hear or see in our daily lives in Japan. IBA forms for which we got at least 10 hits were included. As a result, we obtained 130 i-IBAs and 178 na-IBAs, with 112 stems appearing in both i- and na-forms (see Supplementary material for the full lists).

3.1 Semantic gaps

We identified six semantic/syntactic types of IBAs: Association, Dissociation, Sequence, Determination, Degree, and Incorporation.Footnote 3 While na-IBAs cover all six meanings, i-IBAs appear to lack the Sequence and Determination types.Footnote 4

In the Association type, the two elements (henceforth, X and Y) are semantically connected by AND, as in aza-{kawai-i/kawa-na} ‘be shrewd and cute’ and yuru-daru-{i/na} ‘be loose and languid’. This type of IBA is semantically double-headed.

In the Dissociation type, on the other hand, X and Y are coordinated by BUT, as in kimo-{kawai-i/kawa-na} ‘be weird but cute’ and uza-{kawai-i/kawa-na} ‘be annoying but cute’. Dissociative binomials are right-headed in that, for example, kimo-kawai-i ‘be weird but cute’ is a kind of kawai-i ‘be cute’, rather than kimo-i ‘be weird’, and expresses a positive evaluation.

In the Sequence type, X and Y represent two properties that are perceived sequentially, as in huwa-toro-na ‘be first fluffy, then creamy (of an omelet)’ and kari-mohu-na ‘be first crisp, then soft (of a melon-shaped sweet bun)’. We have not found any single i-IBA form for sequence, and constructed examples such as *huwa-toro-i and *kari-mohu-i clearly sound unnatural. (These examples, whose second element is an ideophone root, are also ruled out by the structural requirement that i-IBAs have an adjective as their second element. See Sect. 3.2.)

In the Determination type, X represents the cause of the perception expressed by Y, as in saku-uma-na ‘be crunchy and therefore yummy (of a pork cutlet)’ and toro-uma-na ‘be tender and therefore yummy (of stewed pork)’. I-IBAs do not cover this meaning, either (e.g., *saku-uma-i, *toro-uma-i).

In the Degree type, X specifies the degree of the state represented by Y. Most X elements are intensifiers (e.g., geki-mazu-{i/na} ‘taste terribly bad’, metya-{kawai-i/kawa-na} ‘be incredibly cute’, yaba-uma-na ‘be awfully yummy’), whereas some deemphasize Y (e.g., tyoi-waru-na ‘be a little bit like a playboy’).Footnote 5

The Incorporation type is a syntactically defined category in which the predicate Y incorporates X that is either an argument or adjunct. In huk-karu-{i/na} ‘be light-footed’ and ata-oka-na ‘be crazy’, huk (< hutto) ‘foot’ and atama ‘head’ are internal arguments of karu-i ‘be light’ and okasi-i ‘be crazy’, respectively. Incorporation-type adjectives are subject to the First Sister Principle, which states that verbs can only incorporate words in their first sister position (Roeper and Siegel, 1978). Therefore, X cannot be an external argument of Y, as shown by the ill-formedness of *ozi-kake-na ‘be man-wearing (of glasses)’ and *zyosi-nomi-na ‘be girl-drinking (of alcohol)’.

The current classification is based on the most likely phrasal paraphrase of each IBA. For example, aza-kawai-i and aza-kawa-na were classified into the Association type because they can be paraphrased as azato-ku-te kawai-i ‘be shrewd and cute’. Likewise, ata-oka-na was classified into the Incorporation type because it can be paraphrased as atama-ga okasi-i ‘be crazy in the head’. More than one paraphrase is available for many IBAs. For example, tibi-kawai-i and tibi-kawa-na can be paraphrased as tibi-dakedo kawai-i ‘be small but cute’ (dissociative reading) or tibi-de kawai-i ‘be small and cute’ (associative reading), depending on the context. While a person who thinks that being small is an unfavorable attribute will obtain the dissociative reading, a person who thinks that being small is a favorable attribute will obtain the associative (or even determinative) reading. We assume that these potential ambiguities reinforce, rather than reject, the classification, as the six semantic types cover all attested IBAs.Footnote 6

Table 1 summarizes the availability of both suffixes in the six types of IBAs. The Sequence and Determination types are exclusive to na-IBA forms. These semantic gaps in i-IBAs will be accounted for in terms of their semiotic difference from na-IBAs in Sect. 4.

3.2 Structural gaps

Another set of derivational gaps is attributed to the syntactic and morphophonological differences between i-IBAs and na-IBAs. The two types of IBAs have their own structural specifications that limit their coexistence.

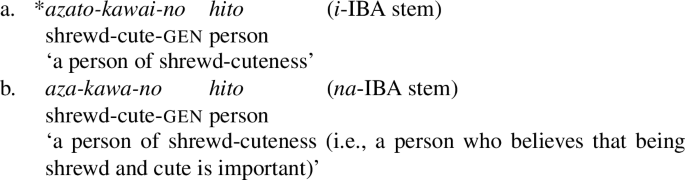

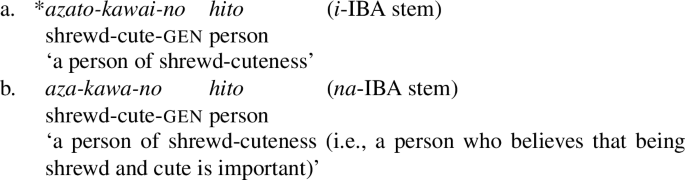

Inheriting the bipartite adjective system of Japanese, the stems of i-IBAs are canonical adjectives, whereas those of na-IBAs are nominals (Miyagawa, 1987; Murasugi, 1990; Nishiyama, 1999). Genitive insertion, for example, reveals this syntactic contrast between the two types of adjectives. The genitive Case marker can be inserted only between a nominal/postpositional phrase and a nominal head, as shown in (8a, b). It is never inserted between a verbal phrase and a nominal head, as in (8c).

-

(8)

This contrast indicates that the genitive Case marker is only compatible with non-verbal elements. As illustrated in (9), genitive insertion is possible with the stems of numerous na-adjectives (e.g., kenkoo-na ‘be healthy’), but not of i-adjectives (e.g., tuyo-i ‘be strong’), suggesting the non-verbal status of na-adjective stems (for the syntactic status of Japanese adjectives, see also fn. 10).

-

(9)

The same holds true for the stems of the two types of IBAs, as in (10).

-

(10)

These data indicate that the stems of i-IBAs and those of na-IBAs have distinct syntactic properties.

From this observation, it follows that IBA stems are compatible with both suffixes only when they have both verbal and non-verbal properties. No IBA stem is syntactically ambiguous in a strict sense. However, as suggested in Sect. 1, two groups of IBA stems exhibit apparent syntactic ambiguity. First, numerous IBA stems are segmentally identical in their i- and na-forms (e.g., daru-omo-i and daru-omo-na ‘be languid and heavy’, oni-mazu-i and oni-mazu-na ‘taste terribly bad’). However, these stems have different accent patterns according to their suffix selection (e.g., daru-omó-i vs. daru-omo-na0 ‘be languid and heavy’, oni-mazú-i vs. oni-mazu-na0 ‘taste terribly bad’). Second, i-IBA stems whose second element is kawai(-i) ‘(be) cute’ have their four-mora truncated counterparts that function as na-IBA stems (e.g., azato-kawai-i and aza-kawa-na ‘be shrewd and cute’, ero-kawai-i and ero-kawa-na ‘be sexy and cute’). In these examples, i-IBAs and na-IBAs form doublets, taking different suffixes according to their syntactic status.

Apparent syntactic ambiguity of these types are not found in two major cases. First, na-IBAs whose second element is a verb or ideophone do not have their i-IBA counterparts. For example, dasa-ike-na ‘be unfashionable but cool’ consists of the adjective dasa-i ‘be unfashionable’ and the casual verb ike-te-ru ‘be cool’, and its i-IBA counterpart (i.e., *dasa-ike-i) does not exist. Similarly, yuru-huwa-na ‘be loose and fluffy’ consists of two ideophones (i.e., yuruyuru ‘loose’ and huwahuwa ‘fluffy’) and does not have its i-IBA counterpart (i.e., *yuru-huwa-i). These forms are ruled out because the second element of i-IBAs is always an adjective stem (e.g., azato-kawai-i (A + A) ‘be shrewd and cute’, metya-emo-i (aff + A) ‘be very emotional’), whereas that of na-IBAs can be an (often truncated) adjective (e.g., aza-kawa-na (A + A) ‘be shrewd and cute’), verb, or ideophone.

Second, some i-IBAs whose stems are either three moras or more than four moras long do not have their na-IBA counterparts. Na-IBAs, but not i-IBAs, are subject to a strict phonological constraint: they must be four moras long (Akita & Murasugi, 2022). Because of this phonological uniformity, do-uma-i ‘be absolutely yummy’ (3 moras) cannot be made into a na-IBA, as in (11a). For the same reason, as mentioned in Sect. 1, both the first and second elements are often truncated in na-IBAs (e.g., azato-i ‘be shrewd’ + kawai-i ‘be cute’ → aza-kawa-na ‘be shrewd and cute’; yuruyuru ‘loose’ + huwahuwa ‘fluffy’ → yuru-huwa-na ‘be loose and fluffy’). Moreover, this phonological constraint appears to prevent some long i-IBAs from creating new na-IBAs. Compare (11b, c) and (11d, e).

-

(11)

-

a.

do-uma-i ‘be absolutely yummy’ (1 mora + 2 moras) > *do-uma-na

-

b.

daru-omo-i ‘be languid and heavy’ (2 moras + 2 moras) > daru-omo-na

-

c.

dera-uma-i ‘be very yummy’ (2 moras + 2 moras) > dera-uma-na

-

d.

kakko-kawai-i ‘be cool and cute’ (3 moras + 3 moras) > *kakko-kawai-na

-

e.

bari-sindo-i ‘be very tough’ (2 moras + 3 moras) > *bari-sindo-na

-

a.

The i-IBAs daru-omo-i and dera-uma-i consist of two bimoraic elements, so they can readily create their na-IBA counterparts. However, the i-IBAs kakko-kawai-i and bari-sindo-i contain trimoraic elements (i.e., kakko(i-i) ‘be cool’, kawai(-i) ‘be cute’, sindo(-i) ‘be tough’) and, therefore, do not fit the four mora template. It would in theory be possible to truncate these elements to fit them into the template. However, expected na-IBA forms, such as kako-kawa-na and bari-sido-na, are not common.Footnote 7

Thus, the derivational gaps in i- and na-IBAs can be attributed to the semantic and structural characteristics of the two adjective forms. In the next section, we develop the current discussion by elaborating on the detailed specifications of the two types of IBAs within the framework of RM.

4 IBA doublets in RM

The formal and functional properties of i- and na-IBAs observed in Sect. 3 can be formulated in terms of output-oriented word-formation rules that are represented as sister schemas. Here, we identify the two schemas and discuss their productivity.

4.1 Sister schemas

As we discussed in Sect. 3, the two types of IBAs differ from each other in several respects. Na-IBAs, but not i-IBAs, can express sequence and determination. I-IBA stems are canonical adjectives, whereas na-IBA stems are nominals. All i-IBAs have an adjective as their second element, whereas na-IBAs consist of various types of roots. I-IBAs are accented and vary in length, whereas na-IBAs are unaccented and four moras long.

All these features can be represented as specifications of the morphological schemas for i-IBAs and na-IBAs. (12) is the schema for i-IBAs. The past tense forms of i-IBAs, such as azato-kawai-katta ‘was/were shrewd and cute’, are generated by another schema that is in a sister relation to this schema.

-

(12)

Schema for i-IBAs:Footnote 8,Footnote 9

Semantics:

[BEnpst (X, [PROPERTY]y × [PROPERTY]z)]x

Morphosyntax:

[V [A — Az] aff6]x

Phonology:

/[μμ<…>]y [μμ<…>]z i6/x

The phonological level, in which <…> stands for an optional element, specifies the first and second elements as at least two moras long. (The absence of superscript 0 in phonology indicates that i-IBAs are accented.) As coindexes y and z indicate, the two elements represent different properties. The two properties are connected by a multiplication sign, which we introduce to represent semantic integration. The morphosyntactic level specifies both the second element and the whole stem as canonical adjectives. The morphosyntactic properties of the first element are left underspecified, which is indicated by the symbol “—.”

(13) is the schema for na-IBAs. The past tense forms of na-IBAs, such as aza-kawa-datta ‘was/were shrewd and cute’, are generated by another schema that is in a sister relation to this schema.

-

(13)

Schema for na-IBAs:

Semantics:

[BEnpst (X, [PROPERTY]y + [PROPERTY]z)]x

Morphosyntax:

[V [N — —] aff7]x

Phonology:

/[[μμ]y [μμ]z]0 na7/x

The phonological level states that the stem is unaccented and consists of two bimoraic elements, which correspond to the two properties in semantics. The two properties are combined by a plus symbol, which we introduce as a connector that preserves the connected elements as are. Morphosyntax specifies the stem as nominal. Note, however, that coindexes y and z are not fully accurate in that the two elements are often truncated and their meanings should be attributed to their non-truncated stems.

The different semantic connectors in (12) and (13) represent the different semantic ranges between the two types of IBAs. The two properties are fully integrated with each other in i-IBAs but are retained in na-IBAs. Due to their semantic retention, na-IBAs can iconically express sequence and determination in which two properties are perceived in temporal and causal order, respectively (for iconicity of linearity, see e.g., Haiman, 1980). For example, huwa-toro-na represents a sequential mouth feel of a food (e.g., omelet) whose surface is fluffy (huwahuwa) and whose inside is creamy (torotoro). The reversed word toro-huwa-na would mean the opposite ‘be first creamy and then fluffy’ (Akita & Murasugi, 2022). Likewise, saku-uma-na means ‘be crunchy (sakusaku) and therefore yummy (uma-i)’. As the two perceptions in the Determination type are unlikely to be reversible, reversed na-IBAs in this type are unacceptable (e.g., *uma-saku-na ‘be yummy and therefore crunchy’).

This special semiotic characteristic of na-IBAs can be ascribed to their ideophone-like status. The four mora form, which is known as the “bimoraic root template” (Poser, 1990), the unaccented prosody, and the copula together make na-IBAs resemble reduplicated adjectival ideophones (e.g., huwahuwa-na0 ‘be fluffy’, meromero-na0 ‘be too fond’, sarasara-na0 ‘be dry and smooth’), schematically represented in (14).Footnote 10

-

(14)

Schema for reduplicated adjectival ideophones:

Semantics:

[BEnpst (X, VERY PROPERTYy)]x

Morphosyntax:

[V [N — —] aff7]x

Phonology:

/[[μμ]y [μμ]y]0 na7/x

In fact, na-IBAs and reduplicated adjectival ideophones show parallel syntactic behaviors (Sells, 2017), as in (15).Footnote 11

-

(15)

As ideophones are iconic lexemes, it appears to be this parallelism that allows na-IBAs to represent sequence and determination in an iconic fashion.

The doublet relation between i-IBAs and na-IBAs can be captured by representing the two schemas as sister schemas, as in (16).

-

(16)

Coindexes α and β in phonology stipulate that i-IBAs and their corresponding na-IBAs share the two initial moras of the two elements. As coindexes γ and δ indicate, the two (often truncated) elements of na-IBAs indirectly refer to the semantic components of i-IBAs. This representation solves the na-IBA schema’s inaccuracy problem in (13).Footnote 12 Moreover, coindexes β and δ together entail that only na-IBAs whose second element is a canonical adjective may have their i-IBA counterparts.

The current RM account straightforwardly captures the different but interrelated word-formation rules for i-IBAs and na-IBAs. Crucially, this account demonstrates that the two types of IBAs constitute a doublet system that is based on a pair of sister schemas. These schemas underly the considerable etymological overlap between i-IBAs and na-IBAs and their near interchangeability. In the next subsection, we discuss the productivity of the two schemas and their subschemas to further clarify the entire morphological network.

4.2 Productivity

Both i-IBAs and na-IBAs are notably productive in present-day colloquial Japanese, and this fact underlies the doublet system that makes IBAs different from conventional adjectives (Sect. 1). However, na-IBAs are more productive than i-IBAs (see Table 1 above), and a systematic comparison between the two types of IBAs in terms of productivity allows us to paint the whole picture of their morphological competition.

The greater productivity of na-IBAs is based on the strong output constraints on them described in Sect. 4.1. The well-defined schematic template in (13) allows native speakers to create new forms, one after another (Booij, 2010; Jackendoff & Audring, 2020). Moreover, the role of na-adjectives in the Japanese lexicon contributes to the productivity of na-IBAs. While the majority of i-adjectives are native, non-ideophonic lexemes (e.g., utukusi-i ‘be beautiful’, kawai-i ‘be cute’), numerous na-adjectives belong to the ideophonic (e.g., betobeto-na ‘be sticky’), Sino-Japanese (e.g., kirei-na ‘be beautiful’), or loaned strata (e.g., kyuuto-na ‘be cute’). Thus, na-adjectives invite new entries and expand the lexicon. Na-IBAs appear to inherit this lexical property from na-adjectives.

I-IBAs often give rise to na-IBAs, but the opposite direction of derivation is limited. For example, the NINJAL Web Japanese Corpus (NWJC), which consists of a billion sentences from the internet in 2014, contains numerous instances of azato-kawai-i ‘be shrewd and cute’ (N = 179) and its clipped form aza-kawai-i (N = 8), but not of aza-kawa-na, which appears to be a more recent innovation. Similarly, the NWJC contains 189 instances of daru-omo-i ‘be languid and heavy’ but only 81 instances of daru-omo-na, suggesting the later emergence of the latter. Derivations from na-IBAs to i-IBAs are only possible when the second element is a non-truncated adjective, as i-IBAs typically do not involve truncation. Rare examples include huk-karu-na ‘be light-footed’, whose second element is identical to the adjective stem karu(-i) ‘be light’. This na-IBA very recently gave rise to its i-IBA counterpart huk-karu-i. The NWJC does not contain any single instance of either form, but huk-karu-na is much more frequent than huk-karu-i on Google (last access: 19 June 2021), which suggests that the na-form appeared first. These facts indicate that na-IBAs are easier than i-IBAs to create.

The highly templatic derivation of na-IBAs contrasts sharply with the analogical (i.e., item- or subschema-based) derivation of i-IBAs (for a related discussion, see Booij, 2010: 88–93). The morphological network of i-IBAs is crucially based on a small set of adjectives and prefixes. For example, 50 out of 130 i-IBAs (38.46%) have kawai(-i) ‘be cute’ as their second element, whereas X-kawa-na only accounts for 26.40% (47/178) of na-IBAs. Examples of X-kawai-i are cited in (17). Among these examples, kakko-kawai-i and otona-kawai-i do not have their na-IBA counterparts (*kakko-kawa-na, *otona-kawa-na; see Sect. 3.2).

-

(17)

azato-kawai-i ‘be shrewd and cute’

dasa-kawai-i ‘be unfashionable but cute’

emo-kawai-i ‘be emotional and cute’

ero-kawai-i ‘be sexy and cute’

kakko-kawai-i ‘be cool and cute’

kimo-kawai-i ‘be weird but cute’

oni-kawai-i ‘be terribly cute’

otona-kawai-i ‘be adult and cute’

ozi-kawai-i ‘be like a middle-aged man but cute’

uza-kawai-i ‘be annoying but cute’

yuru-kawai-i ‘be loose and cute’

Likewise, the prefixoid kuso- ‘very’ (< kuso ‘shit’) accounts for 9.23% (12/130) of i-IBAs, but 6.74% (12/178) of na-IBAs. Other prefixes, such as baka- ‘ridiculously’, bari- ‘very’, gero- ‘incredibly’, and oni- ‘terribly’, also have remarkable productivity. All kuso-Y-i expressions are listed in (18). All these i-IBAs have their na-IBA counterparts, although some of them are not very common.

-

(18)

kuso-dasa-i ‘be very unfashionable’

kuso-deka-i ‘be very big’

kuso-kawai-i ‘be very cute’

kuso-kimo-i ‘be very weird’

kuso-mazu-i ‘taste very bad’

kuso-muzu-i ‘be very difficult’

kuso-nemu-i ‘be very sleepy’

kuso-syaba-i ‘have no guts at all’

kuso-tuyo-i ‘be very strong’

kuso-tyoro-i ‘be very easy’

kuso-uma-i ‘be very yummy’

kuso-yaba-i ‘be very dangerous/good’

Thus, i-IBAs are relatively more dependent on analogical word-formations based on particular Xs and Ys than na-IBAs. It appears that this situation is partly attributed to the fact that i-IBAs only have loose output requirements, as shown in (12). The absence of a detailed schema presumably keeps i-IBAs from achieving full productivity.Footnote 13

Jackendoff and Audring (2020:52) distinguish productive and nonproductive schemas, arguing that the former have both relational and generative functions, whereas the latter only have a relational function. Individual IBAs (e.g., azato-kawai-i ‘be shrewd and cute’ and daru-omo-i ‘be languid and heavy’) are related to each other via the i- and na-IBA schemas, and i-IBAs and na-IBAs (e.g., azato-kawai-i and aza-kawa-na ’be shrewd and cute’) are also related to each other via these sister schemas. The discussion here suggests that the na-IBA schema additionally has a generative function, readily giving birth to new instances, whereas the i-IBA schema has not gained this function yet. Particular subschemas of the i-IBA schema, such as the X-kawai-i schema and the kuso-Y-i schema, instead serve the generative function, creating analogical neologisms. (The corresponding subschemas for na-IBAs also have the generative function.)

These characteristics of the IBA schemas can be incorporated into our schema representations by notating “open” (productive) variables with double underlines and “closed” (nonproductive) variables with single underlines (Jackendoff & Audring, 2020:42), as in (19).

-

(19)

The high productivity of both X-kawai-i and X-kawa-na can be captured by the sister schemas in (20), whose variables all have double underlines.

-

(20)

In summary, RM’s sister schemas allow us to understand the competing relationship between i-IBAs and na-IBAs and their different productivity. The current findings illustrate that RM, which has been primarily developed for the morphological analysis of Germanic languages, has a broader applicability, suggesting the universal architecture of the lexicons of human languages.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we have investigated the competing system of i- and na-IBA doublets. We have shown that the independently established schemas for the two types of adjectives, which were described in terms of sister schemas, account for the apparent derivational gaps. It is expected that sister schemas can also clearly represent similar phenomena in derivation and inflection, including overabundance (e.g., the coexistence of burned and burnt in English; Thornton, 2019), and help discuss the similarities and differences between them. We hope that future research will examine how far this approach can be extended in the morphological discussion of competition.

Abbreviations

acc = accusative, cop = copula, gen = genitive, idph = ideophone, nom = nominative, npst = nonpast, pst = past, top = topic, μ = mora, 0 = unaccented, — = unspecified.

Corpora

National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics. Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese.

National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics. NINJAL Web Japanese Corpus.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Change history

07 February 2023

The original version of this article has been revised: The Authors’ contributions statement has been corrected.

07 February 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-023-09402-x

Notes

The adjective stem kawai ‘cute’ happens to end with /i/, which is not the nonpast tense morpheme.

“Doublets” traditionally mean etymological twins, two distinct words that derive from the same word, often via different routes (e.g., corona and crown < Lat. corōna).

We are indebted to an anonymous reviewer for some of these labels. “Association,” “Dissociation,” “Determination,” and “Incorporation” correspond to “Synonymy,” “Antonymy,” “Causation,” and “Argument-predicate” in Akita and Murasugi (2022).

Akita and Murasugi (2022) discuss the irreversibility of all six types of IBAs in terms of phonological, morphological, and syntactic constraints.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for turning our attention to this issue.

Both kakko(i-i) and sindo(-i) contain a stem-medial coda (i.e., /k/ and /n/). It might be that deleting these consonants in truncation makes it hard to recover the base forms. Note that deleting the third mora (i.e., /ko/ and /do/) would create monosyllabic roots (i.e., *kak-kawa-na, *bari-sin-na), making the base forms even less accessible (Itô, 1990).

More detailed discussion is needed on the syntax of both i- and na-adjectives, including i- and na-IBAs (see Murasugi, 1990, among others). We assume that only the stems of na-adjectives (e.g., siawase ‘happy’, aza-kawa ‘shrewd and cute’) are associated with [–V], and both types of adjectives (e.g., siawase, aza-kawa, uresi ‘happy’, azato-kawai ‘shrewd and cute’) are associated with [+V] when combined with inflectional suffixes.

It would also be possible to add another representational level for register information (i.e., “casual”) to the schemas for both i-IBAs and na-IBAs (Jackendoff & Audring, 2020:246–248).

Adjectival ideophones generally prefer the genitive or adnominal copula -no to -na in their attributive uses (e.g., huwahuwa-no omuretu ‘a fluffy omelet’).

Coindexes γ and δ would also indicate the link between IBAs and their component lexemes. For example, in both azato-kawai-i and aza-kawa-na ‘be shrewd and cute’, the first element directly or indirectly refers to the meaning of its corresponding adjective azato-i ‘be shrewd’, and the second element to the meaning of its corresponding adjective kawai-i ‘be cute’.

As an anonymous reviewer noted, a diachronic observation of individual IBAs would be needed to clarify the whole story of the still developing morphological network of these adjectives. For example, it is likely that the derivation of particular IBAs (e.g., aza(to)-kawai-i > aza-kawa-na ‘be shrewd and cute’) connected the two originally independent IBA schemas, giving rise to the current doublet system.

References

Akita, K., & Murasugi, K. (2022). Innovative binomial adjectives in Japanese food descriptions and beyond. In K. Toratani (Ed.), The language of food in Japanese: Cognitive perspectives and beyond (pp. 111–132). Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Baker, M. (2003). Verbal adjectives as adjectives without phi-features. In Y. Otsu (Ed.), Proceedings of the Fourth Tokyo Conference on Psycholinguistics (pp. 1–22). Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Bonami, O., & Strnadová, J. (2019). Paradigm structure and predictability in derivational morphology. Morphology, 29, 167–197.

Booij, G. (2010). Construction morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fradin, B. (2019). Competition in derivation: What can we learn from French doublets in -age and -ment? In F. Rainer, F. Gardani, W. U. Dressler, & H. C. Luschützky (Eds.), Competition in inflection and word-formation (pp. 67–93). Cham: Springer.

Gardani, F., Rainer, F., & Luschützky, H. C. (2019). Competition in morphology: A historical outline. In F. Rainer, F. Gardani, W. U. Dressler, & H. C. Luschützky (Eds.), Competition in inflection and word-formation (pp. 3–36). Cham: Springer.

Haiman, J. (1980). The iconicity of grammar: Isomorphism and motivation. Language, 56, 515–540.

Hoeksema, J. (2012). Elative compounds in Dutch: Properties and developments. In G. Oebel (Ed.), Intensivierungskonzepte bei Adjektiven und Adverben im Sprachenvergleich / Crosslinguistic comparison of intensified adjectives and adverbs (pp. 97–142). Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovač.

Hüning, M., & Booij, G. (2014). From compounding to derivation: The emergence of derivational affixes through “constructionalization”. Folia Linguistica, 48, 579–604.

Itô, J. (1990). Prosodic minimality in Japanese. Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS), 26(2), 213–239.

Itô, J., & Mester, R. A. (1999). The phonological lexicon. In N. Tsujimura (Ed.), The handbook of Japanese linguistics (pp. 62–100). Malden, MA & Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Jackendoff, R. (2002). Foundations of language: Brain, meaning, grammar, evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackendoff, R., & Audring, J. (2020). The texture of the lexicon: Relational morphology and the parallel architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kubozono, H. (Ed.) (2015). Handbook of Japanese phonetics and phonology. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter Mouton.

Labrune, L. (2012). The phonology of Japanese. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miyagawa, S. (1987). Lexical categories in Japanese. Lingua, 58, 144–184.

Murasugi, K. (1990). Adjectives, nominal adjectives and adjectival verbs in Japanese: Their lexical and syntactic status. UConn Working Papers in Linguistics, 3, 55–86.

Nihon kokugo daijiten (2007). [A comprehensive dictionary of the Japanese language] (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Shogakukan.

Nishiyama, K. (1999). Adjectives and the copulas in Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 8, 183–222.

Plag, I. (2000). On the mechanisms of morphological rivalry: A new look at competing verb-deriving affixes in English. In B. Reitz & S. Rieuwerts (Eds.), Anglistentag 1999 Mainz (pp. 63–76). Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

Poser, W. J. (1990). Evidence for foot structure in Japanese. Language, 66, 78–105.

Roeper, T., & Siegel, M. E. A. (1978). A lexical transformation for verbal compounds. Linguistic Inquiry, 9(2), 199–260.

Sells, P. (2017). The significance of the grammatical study of Japanese mimetics. In N. Iwasaki, P. Sells, & K. Akita (Eds.), The grammar of Japanese mimetics: Perspectives from structure, acquisition, and translation (pp. 7–19). London: Routledge.

Štekauer, P. (2014). Derivational paradigms. In R. Lieber & P. Štekauer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of derivational morphology (pp. 354–369). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stump, G. (2019). Some sources of apparent gaps in derivational paradigms. Morphology, 29, 271–292.

Taniwaki, Y. (1997). Nihongo no fukugō keiyōshi ni okeru rendaku genshō [Rendaku in compound adjectives in Japanese]. Jimbun Ronkyū, 47, 225–246.

Thornton, A. M. (2019). Overabundance: A Canonical Typology. In F. Rainer, F. Gardani, W. U. Dressler, & H. C. Luschützky (Eds.), Competition in inflection and word-formation (pp. 223–258). Cham: Springer.

Yumoto, Y. (1990). Nichi/ei taishō fukugō keiyōshi no kōzō: “Meishi + keiyōshi/keiyōdōshi” no kata ni tsuite [The structure of compound adjectives in Japanese and English: The case of “noun + verbal/nominal adjectives”]. Gengo Bunka Kenkyū, 16, 353–372.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Fourth Nanzan-Nagoya Workshop on Mimetics (January 2021) and the 54th Annual Meeting of the Societas Linguistica Europaea (September 2021). We thank both audiences for their valuable feedback. We are also deeply grateful to Olivier Bonami and the two anonymous reviewers of Morphology for their detailed comments. Any remaining inadequacies are ours.

Funding

This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (no. 19H01261) to KA, Pache Research Subsidies I-A-2 for the 2020–2021 academic years to KM, and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (no. 17K02752) to KM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Kimi Akita and Keiko Murasugi,

Methodology: Kimi Akita and Keiko Murasugi,

Data collection: Keiko Murasugi and Kimi Akita,

Formalization: Kimi Akita,

Writing - original draft preparation: Kimi Akita and Keiko Murasugi,

Writing - review and editing: Kimi Akita and Keiko Murasugi,

Funding acquisition: Keiko Murasugi and Kimi Akita.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article has been revised: The Authors’ contributions statement has been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akita, K., Murasugi, K. Binomial adjective doublets in Japanese: A Relational Morphology account. Morphology 32, 281–297 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-022-09395-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-022-09395-z