Abstract

I describe and analyse data from Amarasi, a language with morphological consonant-vowel metathesis. Depending on the phonotactic structure of the stem to which it applies, metathesis is associated with a number of other phonological processes including: vowel deletion, consonant deletion and two kinds of vowel assimilation. By proposing that Amarasi has an obligatory CVCVC foot in which C-slots can be empty all these phonological processes can be derived from a single process of metathesis and one associated morphemically conditioned process. I consider analyses other than the rule-based one adopted in this paper and show that they cannot account for all the data in a consistent, plausible way.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In this paper I describe and analyse the form of metathesis in Amarasi, an Austronesian language of western Timor. At its most simple, metathesis involves the reversal of the final consonant-vowel sequence of a word. One example is the word ‘seven’ which has the unmetathesised form hi

[ˈhi

[ˈhi ʊ] and the metathesised form hi

ʊ] and the metathesised form hi

[ˈhi.ʊ

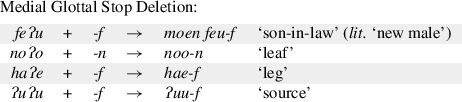

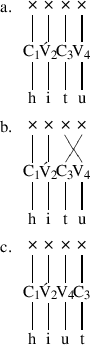

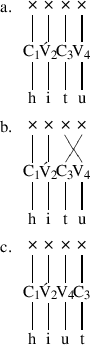

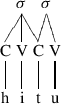

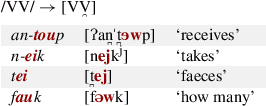

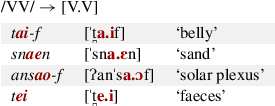

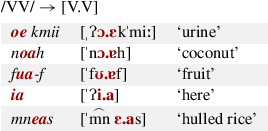

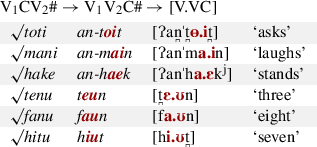

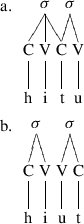

[ˈhi.ʊ ]. This example shows the pattern C1V2C3V4 → C1V2V4C3, illustrated in (1) below.

]. This example shows the pattern C1V2C3V4 → C1V2V4C3, illustrated in (1) below.

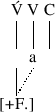

-

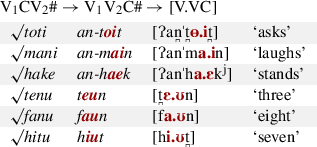

(1)

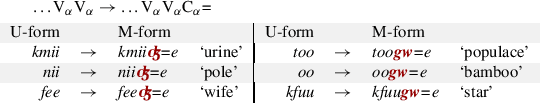

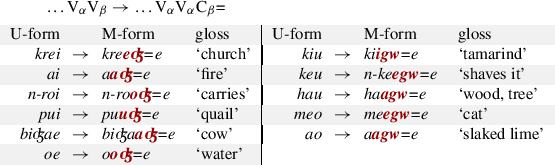

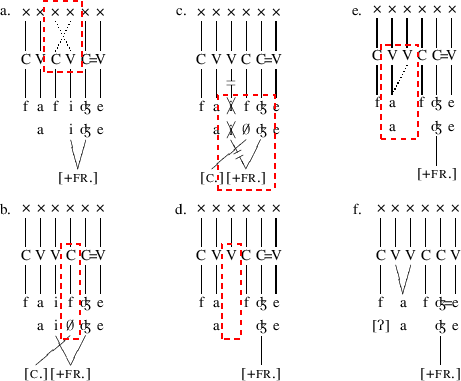

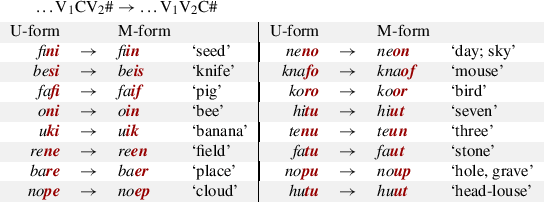

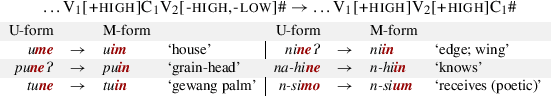

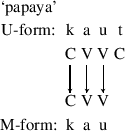

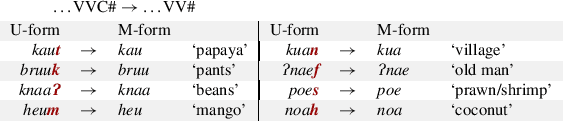

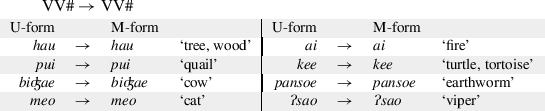

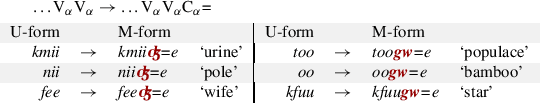

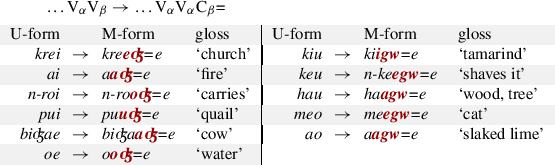

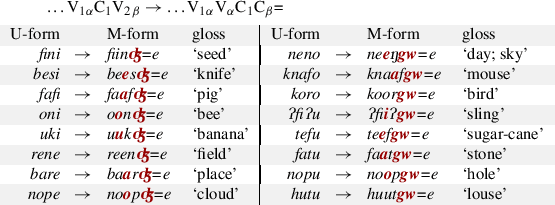

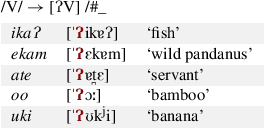

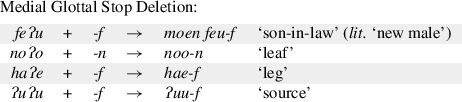

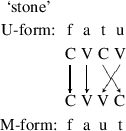

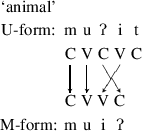

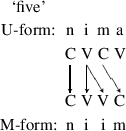

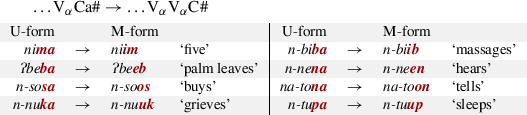

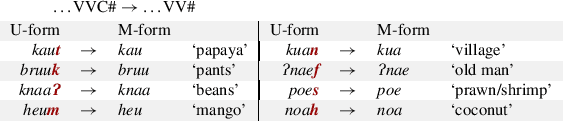

Metathesis is mostly straightforward with roots that instantiate all and only CVCV. However, roots with other shapes also frequently occur in Amarasi. Depending on the phonotactic structure of the word to which it applies, metathesis is associated with a number of other phonological processes including: vowel deletion, consonant deletion and two kinds of vowel assimilation. Some of these different processes are illustrated for different roots of different shapes in Table 1. Such forms all belong to the same paradigm and serve an inflectional purpose, as discussed briefly in Sect. 2.2.

From the examples given in Table 1, it is clear that many of the forms before and after the arrow do not differ only in the order of the final CV sequence. For this reason, I refer to forms paradigmatically equivalent to hitu ‘seven’ as the ‘U-form’ and forms paradigmatically equivalent to hiut ‘seven’ as the ‘M-form’.Footnote 1

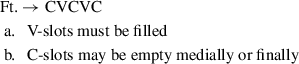

Under a process based model of morphology and an autosegmental model of phonology, by positing an obligatory CVCVC foot in which C-slots can be empty, all the phonological processes in the formation of the M-form arise from a single rule of metathesis at the CV tier, an associated morphemically conditioned rule, and the general phonotactic constraints of Amarasi.

This analysis is superior to alternate analyses under different frameworks, such as prosodic morphology or purely concatenative morphology, neither of which can account for all the data in a consistent, typologically plausible manner.

This paper proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2 I describe the language background and the prosodic and phonotactic structures of Amarasi. Importantly, in most forms, such as hi

[ˈhi

[ˈhi ʊ] → hi

ʊ] → hi

[ˈhi.ʊ

[ˈhi.ʊ ] ‘seven’, M-forms differ only in the order of the final CV sequence—there is no vowel coalescence, diphthongisation, or difference in stress.

] ‘seven’, M-forms differ only in the order of the final CV sequence—there is no vowel coalescence, diphthongisation, or difference in stress.

In Sect. 3 I present the data and describe the different phonological processes by which the M-form is formed in Amarasi. In Sect. 4 I propose a unified analysis under which all these processes are derived from a single morphological process of metathesis at the CV tier. In Sect. 5 I consider alternate analyses which have been proposed for typologically similar processes. I show that while such analyses can account for some of the data, they cannot account for all of the data in Amarasi.

This means that Amarasi presents a true case of morphological metathesis in which metathesis alone—without any additional phonological difference—can be the only expression of a morphosyntactic category.

2 Background

Amarasi is a member of the Uab Meto (a.k.a. Dawan[ese], Timorese, Atoni) cluster of languages/dialects spoken on the western part of the island of Timor. The term ‘Amarasi’ is used by speakers as a label used for the people, speech, and area of the old kingdom of Amarasi. Speakers identify four ‘dialects’ of Amarasi: Kotos, Ro'is, Tais Nonof and 'Hero'.Footnote 2 The dialect which is the focus of this paper is Kotos Amarasi, with occasional reference made to Ro'is Amarasi when it provides comparative insights. The location of Kotos Amarasi and Ro'is Amarasi within the Uab Meto cluster is shown in Fig. 1.

There are differences in the forms and functions of metathesis between different varieties of Uab Meto, different dialects of these varieties, and even between individual villages of a single dialect. Unless stated otherwise, the data presented in this paper come from Kotos Amarasi as spoken in the present day village (desa) of Nekmese' by inhabitants of the historic hamlet (kampung) of Koro'oto.

The data in this paper were collected by the author based on a total of six months fieldwork. These data primarily consist of a dictionary of more than 2,000 unique morphemes and over two and a half hours of recorded, translated, and glossed texts.

2.1 Prosodic and phonotactic background

I describe here the phonotactic and phonological structures of Amarasi as necessary to understand and properly analyse the formation of M-forms. In Sect. 2.1.1 I show that in nearly all circumstances each segmental vowel is the peak of a unique syllable. This includes both vowel sequences in M-forms and sequences of two identical vowels.

In Sect. 2.1.2 I describe stress in Amarasi. I show that word stress is always penultimate. This fact, combined with Amarasi syllabification, means that syllable weight plays almost no role in the Amarasi phonology.

Finally, in Sect. 2.1.3 I show that Amarasi has a highly constrained word structure built around the disyllabic foot. This sets the scene for my analysis in Sect. 6 in which I propose that the foot is obligatorily CVCVC with empty C-slots permitted.

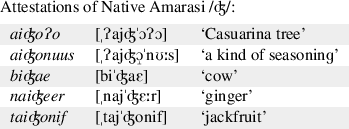

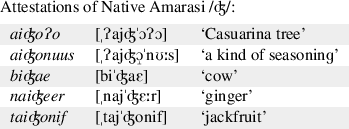

Amarasi has eleven consonants: /p t k ʔ b f s h m n r/ and five vowels: /i e a o u/. In addition, the voiced obstruents /ʤ/ and /gw/ occur mainly in certain morphophonemic environments (see Sect. A.2).Footnote 3 Edwards (2016a) is a more complete description of Amarasi segmental phonology and phonetics.

2.1.1 Vowel sequences and syllabification

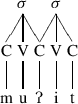

The Amarasi syllable maximally consists of an onset C-slot, a nucleus V-slot and a coda C-slot. Consonant clusters, up to a maximum of two consonants, are only permitted at the beginning of the final/only disyllabic foot of a word and in Sect. 2.1.3 I propose that they are associated with feet, not syllables. Thus the syllable structure can be stated as: σ → (C)V(C). With one exception (discussed in Sect. 2.1.2 below) each segmental vowel is the nucleus of a single syllable.

A word medial C-slot is ambisyllabic (Clements and Keyser 1983:36, Durand 1990:217ff); it is both the coda of the previous syllable and the onset of the second syllable. As a result, the only consonants which are purely codas (and not also onsets) are those which are foot final such as the final consonant of

muʔi

muʔi  ]] ‘animal’ or the first glottal stop in

]] ‘animal’ or the first glottal stop in

ata

ata ]

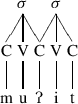

] raʔe]] ‘praying mantis’. The syllabification of the words muʔit [ˈmʊʔi

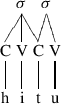

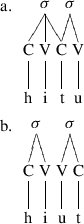

raʔe]] ‘praying mantis’. The syllabification of the words muʔit [ˈmʊʔi ] ‘animal’ and hitu [ˈhi

] ‘animal’ and hitu [ˈhi ʊ] ‘seven’, as well as and the M-form hiut [ˈhi.ʊ

ʊ] ‘seven’, as well as and the M-form hiut [ˈhi.ʊ ] ‘seven’, is shown in (2)–(4) below.

] ‘seven’, is shown in (2)–(4) below.

-

(2)

-

(3)

-

(4)

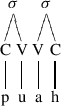

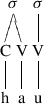

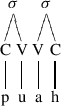

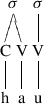

Amarasi permits a maximum of two adjacent vowels. Each vowel of such a vowel sequence is also the nucleus of a single syllable, and in most cases this is transparently realised with two phonetic syllables. The syllabification of puah [ˈpʊ.ɐh] ‘betel-nut’ and hau [ˈha.ʊ] ‘wood, tree’ are shown in (5) and (6) below.

-

(5)

-

(6)

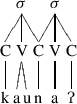

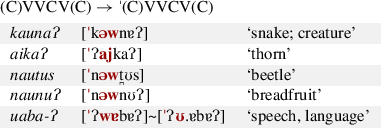

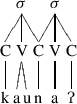

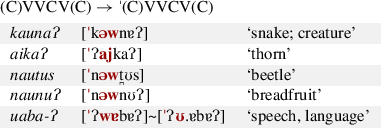

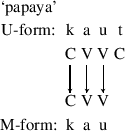

The only case in which a sequence of two vowels is usually the nucleus of a single syllable is words with the surface structure (C)VVCV(C)#, such as kaunaʔ [ˈkəwnɐʔ] ‘snake; creature’. In this case, the first two vowels are assigned to single V-slot and thus by extrapolation form the nucleus of the syllable to which that V-slot belongs. This is discussed in more detail in Sect. 2.1.2 below. The syllabification of kaunaʔ [ˈkəwnɐʔ] ‘snake; creature’ is shown in (7) below.

-

(7)

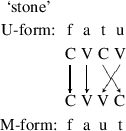

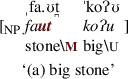

The first vowel of the sequence /au/ is usually centralised in unmetathesised forms in Amarasi. Thus au → [ˈʔə.ʊ] ‘I, 1sg’ and kaut → [ˈkə.ʊ ] ‘papaya’. Such centralisation does not occur in sequences of /au/ created through metathesis, thus fatu [ˈfat

] ‘papaya’. Such centralisation does not occur in sequences of /au/ created through metathesis, thus fatu [ˈfat ] ‘stone, rock’ → faut → [ˈfa.ʊ

] ‘stone, rock’ → faut → [ˈfa.ʊ ].

].

While each segmental vowel (with the exception of surface VVCV(C)# words) is the nucleus of its own syllable there are some situations in which a vowel sequence can optionally coalesce into a single phonetic syllable. This optional surface coalescence does not in any-way affect the underlying syllable structure. Two vowels which have coalesced into a single phonetic syllable remain the peak of two phonemic syllables for the purposes of stress assignment, reduplication, metathesis and all other morphophonemic processes of the language.

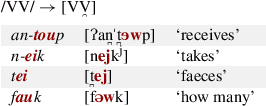

One situation in which two vowels sometimes coalesce into a single phonetic syllable is when the second vowel is higher than the first, in which case the second vowel can be realised as an off-glide. Examples from a recorded word-list are given in (8) below.

-

(8)

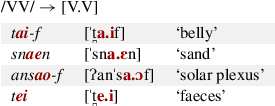

Again, this coalescence is entirely optional, with factors such as speech speed, sentence stress and pragmatics determining whether or not it occurs. Many instances of a vowel followed by a higher vowel do not coalesce into a single phonetic syllable. The underlying structure of two syllables is realised transparently as two phonetic syllables. Examples from a recorded word-list are given in (9) below.

-

(9)

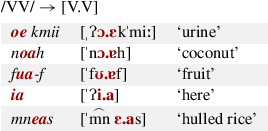

Phonetic coalescence rarely occurs when both vowels of a sequence are of equal height, or when the first vowel is higher than the second. Examples are given in (10) below.

-

(10)

Importantly for any analysis of metathesis in Amarasi, vowel sequences created through metathesis do not obligatorily coalesce. Examples of vowel sequences created through metathesis in which phonetic coalescence has not occurred are given in (11) below. Additionally, in each example in (11), with the exception of hitu ‘seven, the second vowel is higher than the first; the kind of vowel sequence which most commonly coalesces.

-

(11)

This means that both forms of such words have exactly the same prosodic structures. In this respect Amarasi is crucially different from previous descriptions of Kwara’ae (Heinz 2004) and Rotuman (McCarthy 2000). I return to this point in Sect. 5.1.

In Amarasi, the only difference between the unmetathesised form and the metathesised form is the order of the final CV sequence. The syllabification of both forms of ‘seven’ hitu [ˈhi ʊ] and hiut [ˈhi.ʊ

ʊ] and hiut [ˈhi.ʊ ] is given in (12) below.

] is given in (12) below.

-

(12)

Coalescence of two vowels into a single phonetic syllable is more frequent in rapid speech and when the vowel sequence does not bear primary stress. Thus, in the recording of a particular word-list, the word hau ‘tree, wood’ occurred in isolation as [ˈha.ʊ] without the second vowel being realised as an off-glide. However, in the same word-list when the same word occurred in the compound hau noʔo ‘tree leaf’ it was realised as [ˌhawˈnɔʔɔ], with the second vowel desyllabified. Again, such desyllabification is not obligatory and vowel sequences which do not have primary stress also often surface with two phonetic syllables. One example is oe mninuʔ ‘water for drinking’ → [ˌʔɔ.εmˈninʊʔ], from the same word-list.

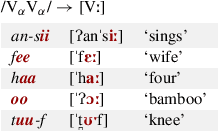

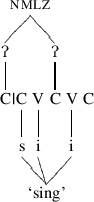

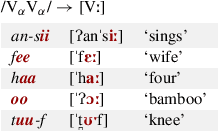

In normal speech a sequence of two identical vowels always coalesces into a single phonetic syllable with a single phonetically long or half-long vowel. Examples are given in (13) below.

-

(13)

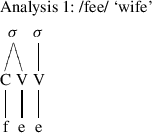

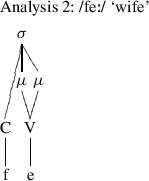

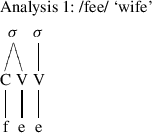

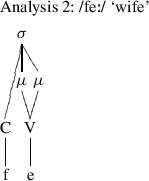

An alternate analysis of such data would be to propose that sequences of two identical vowels are underlyingly long vowels; that is a single vowel linked to two morae. Each of these analyses is shown in for fee ‘wife’ in (14) and (15) respectively.

-

(14)

-

(15)

The reason for analysing such data as representing a sequence of two identical vowels rather than a single long vowel, is that, with the exception of their phonetic realisation, sequences of two identical vowels behave identically in every respect to sequences of two different vowels. This is true of stress assignment (Sect. 2.1.2), reduplication (Sect. 2.1.3) and every other process of the language.

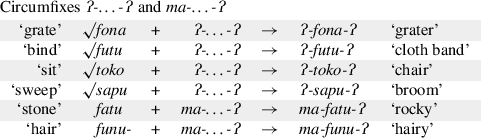

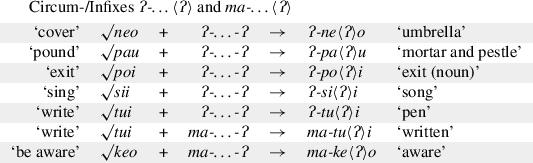

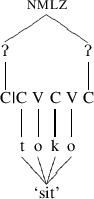

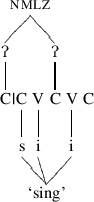

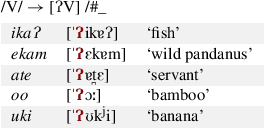

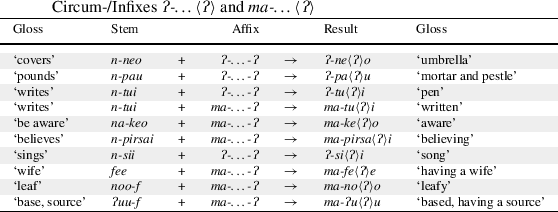

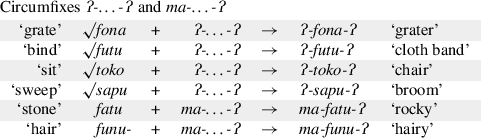

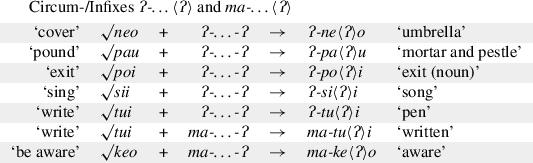

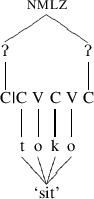

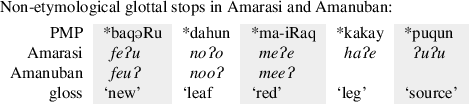

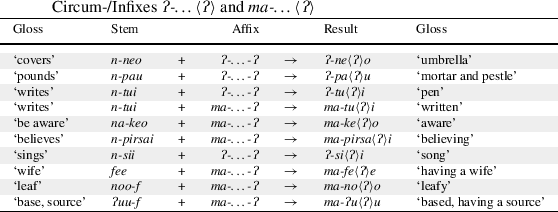

One process which illustrates well the fact that sequences of two identical vowels behave identically to sequences of two different vowels, is glottal stop infixation whereby the second part of each of the nominalising circumfixes ʔ-…-ʔ ‘object nominalisation’ and ma-…-ʔ ‘property nominalisation’ occurs as an infix between the vowels of a final vowel sequence.

When these circumfixes attach to a surface CVCV# root, or VVC# root, the glottal stop occurs word finally. Examples include mone ‘husband’ → ma-mone-ʔ ‘having a husband, married’, puah ‘betel-nut’ → ma-pua-ʔ ‘having betel-nut’,Footnote 4, and n-toko ‘sits’ → ʔ-toko-ʔ ‘chair’.

However, when these circumfixes occur on a root with a final vowel sequence, the second glottal stop occurs between these two vowels as an infix. This includes words with a final sequence of two identical vowels. Examples are given in (16) below.

-

(16)

If words with a sequence of two identical vowels such as fee ‘wife’ were analysed as having a single long vowel, the insertion of a glottal stop in forms such as ma-fe〈ʔ 〉e ‘having a wife’ is completely unexpected; one segment should not be able to occur inside another. However, if such words have a sequence of two vowels, then this behaviour is simply explained by the second element of these prefixes occurring between the two vowel segments.

While sequences of two identical vowels usually coalesce into a single phonetic syllable, each vowel is still treated as the nucleus of a separate syllable with regards to every phonological and morphophonemic process of the language. The only difference between sequences of two identical vowels and sequences of two different vowels is the frequency with which phonetic coalescence occurs: coalescence is almost universal for sequences of two identical vowels and only optional for sequences of two different vowels.

2.1.2 Stress

Word stress in Amarasi falls on the penultimate syllable of the word, with secondary stress assigned to every second syllable to the left; thus ataʔraʔe → [ˌʔɐ ɐʔˈraʔε] ‘praying mantis’. The three main correlates of stress in Amarasi are duration, pitch and intensity. A stressed vowel is typically realised with higher pitch, increased intensity and is longer when compared to unstressed vowels.

ɐʔˈraʔε] ‘praying mantis’. The three main correlates of stress in Amarasi are duration, pitch and intensity. A stressed vowel is typically realised with higher pitch, increased intensity and is longer when compared to unstressed vowels.

A simple example can be seen in the word nisi-f → [ˈnisɪf] ‘tooth’. The spectrogram for one repetition of this word in a word-list is given in Fig. 2. Intensity is shown by the solid yellow line and pitch by the dotted blue lines.

Visually, it is quite clear from Fig. 2 that the initial vowel has a higher pitch as well as increased intensity and duration when compared to the second vowel. The measurements for length, intensity and duration for the initial stressed vowel and final unstressed vowel in this recording are given in Table 2. These figures can be considered broadly representative of the pattern observed for all words.

Words with the surface structure (C)VVCV(C), such as kaunaʔ ‘snake; creature’, are the only words in which the penultimate segmental vowel is not stressed. The initial vowel sequence of such words usually coalesces into a phonetic diphthong, with the higher vowel being realised as an off-glide. The whole phonetic diphthong is then the locus of stress placement. Even when the initial vowel sequence does not coalesce into a phonetic diphthong, it is still the first vowel of such words rather than the penultimate vowel which receives primary stress. Examples are given in (17) below.

-

(17)

Finally, it is worth stating explicitly that stress is identical for both unmetathesised and metathesised forms with stress falling on the penultimate syllable. Three examples from the same word-list are tenu [ˈ εnʊ] → teun [ˈ

εnʊ] → teun [ˈ ε.ʊn] ‘three’, hitu [ˈhi

ε.ʊn] ‘three’, hitu [ˈhi ʊ] → hiut [ˈhi.ʊ

ʊ] → hiut [ˈhi.ʊ ] ‘seven’, and fanu [ˈfanʊ] → faun [ˈfa.ʊn] ‘eight’.

] ‘seven’, and fanu [ˈfanʊ] → faun [ˈfa.ʊn] ‘eight’.

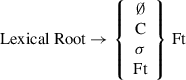

2.1.3 Root structure

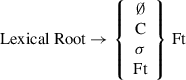

The Amarasi root has a highly constrained structure built around a disyllabic foot. Lexical rootsFootnote 5 are minimally composed of a CV(C)V(C) foot which can optionally be preceded by another foot, a CVC syllable (σ) or a single consonant. The maximum root size is thus quadrisyllabic.Footnote 6 Coda clusters do not occur and consonant clusters almost universally occur only before the penultimate vowel of the foot.Footnote 7

This root structure is given in (18) below. A selection of words illustrating each of the permitted word shapes in Amarasi is given in Table 3. The penultimate vowel of a word bears primary stress, described in more detail in Sect. 2.1.2 above.

-

(18)

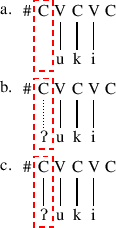

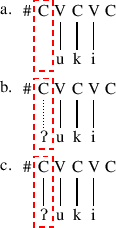

Syllable onsets are optional word medially, but not word initially. When no consonant is specified word initially, a glottal stop is automatically inserted. Two examples are asu → [ˈ  asʊ] ‘dog’ and ataʔraʔe → [ˌ

asʊ] ‘dog’ and ataʔraʔe → [ˌ  ɐ

ɐ ɐʔˈra.ʔε] ‘praying mantis’. Evidence that this is a productive process comes from roots such as √isa ‘most, completely, win’ which do not have a glottal stop when prefixed; n-isa → [ˈnisɐ] ‘3sg/3pl-utterly’, but do have a glottal stop when no prefix occurs; isa-t ‘utterly-nmlz’ → [ˈ

ɐʔˈra.ʔε] ‘praying mantis’. Evidence that this is a productive process comes from roots such as √isa ‘most, completely, win’ which do not have a glottal stop when prefixed; n-isa → [ˈnisɐ] ‘3sg/3pl-utterly’, but do have a glottal stop when no prefix occurs; isa-t ‘utterly-nmlz’ → [ˈ  isɐ

isɐ ]. See Edwards (2017) for more discussion of glottal stop insertion in Amarasi.

]. See Edwards (2017) for more discussion of glottal stop insertion in Amarasi.

Amarasi has a syllabic foot structure in which a foot consists of two syllables. Syllable weight plays no role in the language. That is, Amarasi is not a quantity sensitive language.

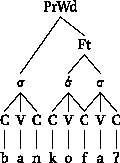

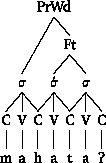

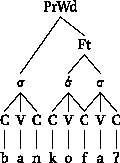

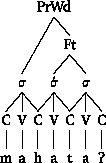

In line with the principle of Foot Binarity (Prince 1980; McCarthy and Prince 1993/2001:46; Hayes 1994) any third syllable is external to the foot and immediately dominated by the prosodic word (PrWd). The structures of bankofaʔ ‘caterpillar’ and mahataʔ ‘itchy’ are shown in (19) and (20) below.

-

(19)

-

(20)

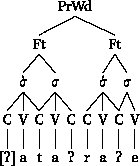

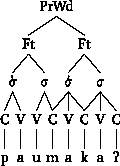

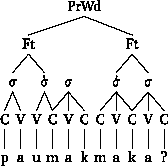

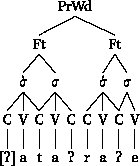

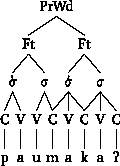

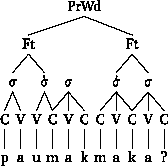

Words which have more than four syllables consist of two feet. The prosodic structures of ataʔaraʔe ‘praying mantis’ and paumakaʔ ‘near’ are shown in (21) and (22) below.

-

(21)

-

(22)

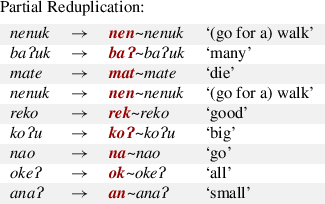

Partial reduplication is a productive morphological process in Amarasi used to form an intensive. It provides support for identifying a CV(C)V(C) foot and (C)V(C) syllable as distinct domains of Amarasi word structure. It also provides evidence that any pre-foot material is not part of the same domain as the foot.

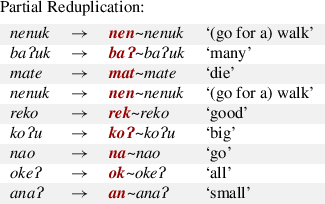

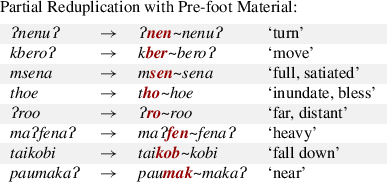

In partial reduplication the initial (and stressed) syllable of the final foot is copied and prefixed to this final foot. For roots which consist of a single foot, this means the reduplicant is simply placed to the left of the stem. Examples are given in (23) below.

-

(23)

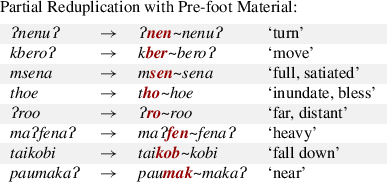

However, when reduplication applies to a root which is larger than a single foot, the CVC reduplicant is placed after the pre-foot material and prefixed to the foot, thus occurring as a kind of infix. Examples are given in (24) below.

-

(24)

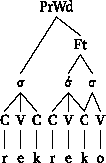

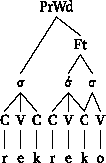

This can be analysed by proposing that the reduplicant is a kind of foot-prefix consisting of a single CVC syllable. The proposed structures of rek~reko ‘good’ and paumak~makaʔ are given in (25) and (26) below.

-

(25)

-

(26)

That the reduplicant in partial reduplication occurs between the foot and any pre-foot material provides evidence that the foot constitutes a distinct domain of Amarasi word structure. That the reduplicant consists of CVC provides support for analysing the Amarasi syllable as having this structure.

2.1.4 Summary

In this section I have discussed the prosodic and phonotactic structures of Amarasi. The following facts are particularly pertinent for analysing M-forms:

-

Sequences of identical vowels behave identically to sequences of different vowels. (They are best analysed as vowel sequences rather than unitary long vowels.)

-

Each vowel is the nucleus of a unique syllable, with the exception of the initial sequence of VVCV# words. (Any coalescence of adjacent vowels is a subsequent, optional, phonetic effect.)

-

Stress falls on the penultimate vowel of the foot. (Stress is identical for U-forms and M-forms. Syllable weight plays no role in stress assignment.)

-

Amarasi words have a highly constrained structure built around the CV(C)V(C) foot.

2.2 Functions of metathesis in Amarasi

M-forms and U-forms in Amarasi are distinct morphological forms. A complete description of the functions of these forms can be found in Edwards (2016b). In this section I provide only a brief overview.

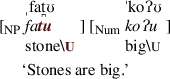

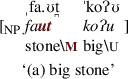

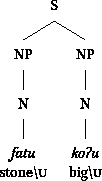

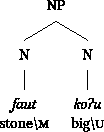

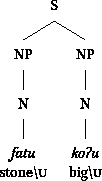

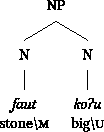

Amarasi M-forms and U-forms have two distinct morphological functions: one to mark syntactic structures and one to mark discourse structures. Syntactically driven metathesis is a morphological device used to mark the presence of an attributive modifier of the same word class as the head. Such M-forms are a construct form.

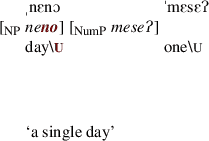

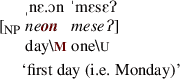

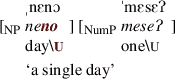

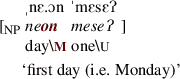

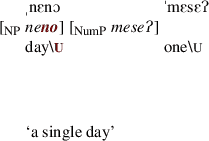

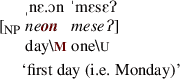

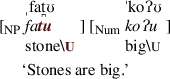

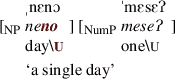

An example of the syntactic function of metathesis can be seen by comparing examples (27) and (28) below. Each consists of the noun neno ‘day’ followed by the numeral meseʔ ‘one’. When the head nominal occurs in the U-form, the numeral is the head of a number phrase and has a cardinal meaning. However, when the head nominal occurs in the M-form, the numeral occurs within the noun phrase and has an ordinal meaning.

-

(27)

-

(28)

-

(29)

-

(30)

Each of the phrases in (27) and (28) has identical intonation and stress. Neither do the vowels of the M-form collapse into a single phonetic syllable. The only phonetic difference between each of these phrases is the order of the final consonant and vowel of the head nominal; metathesis.

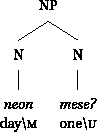

Another example of the syntactic function of metathesis can be seen by comparing examples (31) and (32) below. Example (31) with an initial U-form is an equative clause with two nominals as subject and predicate, while example (32) with an initial M-form consists of a single nominal phrase with the second nominal functioning attributively as a dependent modifier. Each of these phrases also has identical stress and intonation, with the difference in syntactic structure signalled by the metathesis alone.

-

(31)

-

(32)

-

(33)

-

(34)

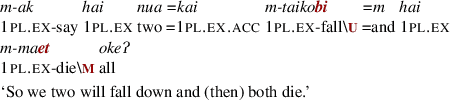

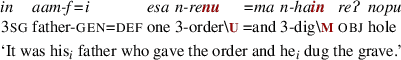

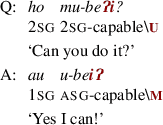

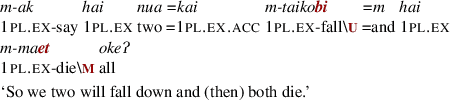

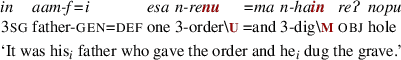

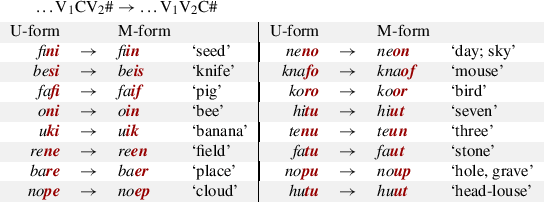

Discourse metathesis marks an unresolved event or situation which requires another clause to achieve resolution. Three examples are given in (35)–(37) below.Footnote 8 Examples (35) and (36) each contain two events. The second event is encoded in the M-form and is dependent on the prior U-form event for its realisation. Example (37) is a question-answer pair in which a question posed in the U-form is resolved by an answer in the M-form. In each of these examples it is ungrammatical for an M-form to be used instead of the U-form.

-

(35)

-

(36)

-

(37)

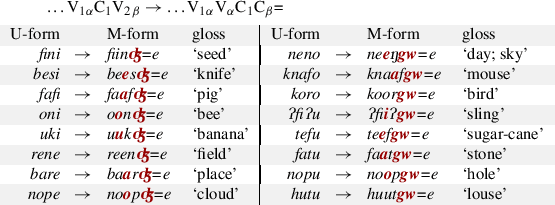

3 The form of the M-form

In this section I describe the different phonological processes used to form the M-form in Amarasi. Which processes occur depends on the phonotactic shape of the U-form stem. These processes include: metathesis (Sect. 3.1), consonant deletion (Sect. 3.2, Sect. 3.4) two kinds of vowel assimilation (Sect. 3.3) and vowel deletion (Sect. 3.5).

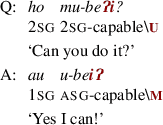

3.1 Metathesis

When a root ends in VCV#, the M-form is formed by metathesis of the final consonant-vowel sequence. The surface relationship between the segments of fatu [ˈfa ʊ] → faut [ˈfa.ʊ

ʊ] → faut [ˈfa.ʊ ] ‘stone’ is shown in (38) below, with more examples given in (39).

] ‘stone’ is shown in (38) below, with more examples given in (39).

-

(38)

-

(39)

It is worth emphasising that in most cases the order of the final consonant and vowel of the word is the only difference between the U-form and the M-form of VCV# final roots.Footnote 9 Metathesis is not accompanied by any reduction in the number of syllables nor by any change in the placement of stress.

Such metathesis applies to all VCV# final roots, with the exception of roots in which the final vowel is /a/ (Sect. 3.3.2) or when the penultimate vowel is high and the final vowel is mid (Sect. 3.3.1). Such roots undergo metathesis followed by vowel assimilation.

3.2 Complication 1: Metathesis and consonant deletion

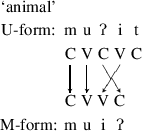

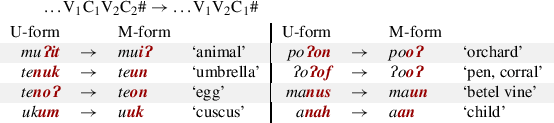

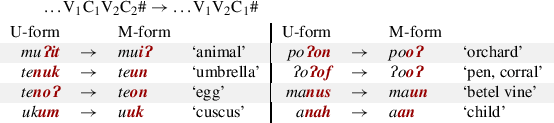

Words with a final consonant (CVC#) derive their M-form through metathesis of the penultimate consonant with the final vowel and deletion of the final consonant. The surface relationship between muʔit [ˈmʊʔi ] → muiʔ [ˈmʊ.iʔ] ‘animal’ is shown in (40) below, with more examples given in (41).

] → muiʔ [ˈmʊ.iʔ] ‘animal’ is shown in (40) below, with more examples given in (41).

-

(40)

-

(41)

Word final consonant clusters are not permitted in Amarasi. The consonant deletion observed in the M-form of VCVC# final words can thus be accounted for by language specific phonotactic constraints. Metathesis occurs, resulting in a disallowed word final consonant cluster which is resolved by deletion of the final consonant.

3.3 Complication 2: Metathesis and vowel assimilation

3.3.1 Mid vowel assimilation

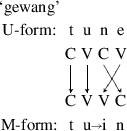

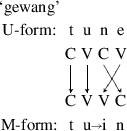

When the final vowel is mid and the penultimate vowel is high, the penultimate vowel is raised to high after metathesis. The surface relationship between the U-form and M-form of tune [ˈ ʊnε] → tuin [ˈ

ʊnε] → tuin [ˈ ʊ.in] ‘gewang palm’ is shown in (42) below, with more examples given in (43).

ʊ.in] ‘gewang palm’ is shown in (42) below, with more examples given in (43).

-

(42)

-

(43)

Words with this shape are uncommon in my corpus with only 22 attestations out of a total of 1,696 unique lexical roots (1.3%). Additionally, the majority of such words have variant U-forms in which the final vowel is raised to high. Examples include um

~ um

~ um

‘house’, tun

‘house’, tun

~ tun

~ tun

‘gewang palm’, na-hin

‘gewang palm’, na-hin

~ na-hin

~ na-hin

‘knows’ and nin

‘knows’ and nin

ʔ ~ nin

ʔ ~ nin

ʔ ‘edge; wing’.

ʔ ‘edge; wing’.

Vowel sequences of a high vowel followed by a mid vowel are not found in Amarasi; there are no attestations of *ie, *io, *ue or *uo. For this reason, the mid vowel assimilation observed when the final vowel is high and the penultimate vowel is mid can be explained by the phonotactic constraints of the language.

3.3.2 Assimilation of /a/

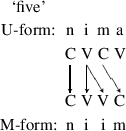

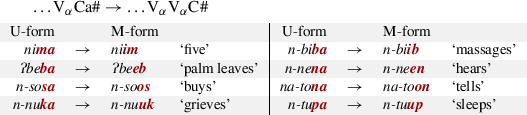

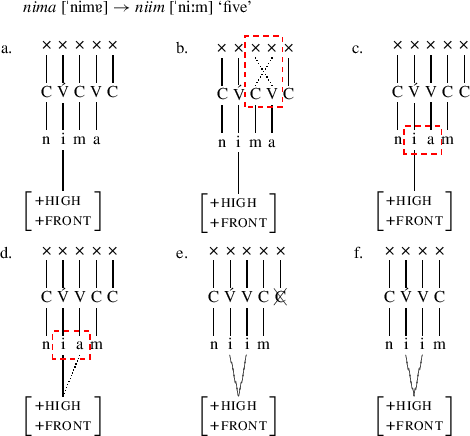

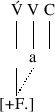

The second kind of vowel assimilation in the formation of M-forms is assimilation of /a/. The M-form of words which end in CVa# is formed via consonant-vowel metathesis with complete assimilation of /a/ to the quality of the first vowel. The surface relationship between the forms nima [ˈnimɐ] → niim [ˈniːm] ‘five’ is shown in (44), with more examples given in (45) below.

-

(44)

-

(45)

Vowel sequences in which the second vowel is /a/ do occur in U-forms, with 83 examples in my current corpus. Eight of these examples are given in (46) below.

-

(46)

The assimilation of /a/ in M-forms is an example of a derived environment effect (Kiparsky 1973; Kenstowicz and Kisseberth 1977), a phonological rule which only operates after the application of another rule. In this case, metathesis triggers assimilation of /a/.

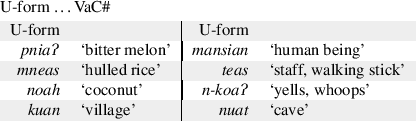

3.4 Complication 3: Consonant deletion

Another complication in the formation of M-forms is found in words which end in VVC# in the U-form. Such words derive their M-form by deletion of the final consonant. The surface relationship between the segments of kaut [ˈkə.ʊ ] → kau [ˈkə.ʊ] ‘papaya’ is shown in (47), with more examples given in (48) below.

] → kau [ˈkə.ʊ] ‘papaya’ is shown in (47), with more examples given in (48) below.

-

(47)

-

(48)

Note that assimilation of /a/ does not occur in such M-forms. In Sect. 3.3.2 I analyse this as being due to the presence of an empty C-slot after /a/ in the M-form of such forms. Comparative evidence for this analysis from Ro'is Amarasi (a different dialect than is the focus of this paper) is also discussed in Sect. 3.3.2.

Unlike the consonant deletion seen for VCVC# words (Sect. 3.2), this consonant deletion cannot be accounted for by surface phonotactic constraints of the language. In Sect. 4 I show that by positing that such words have a medial empty C-slot, this consonant deletion can also be analysed as an automatic result of metathesis and a prohibition against word final consonant clusters, including clusters involving empty C-slots.

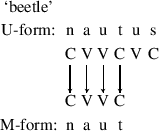

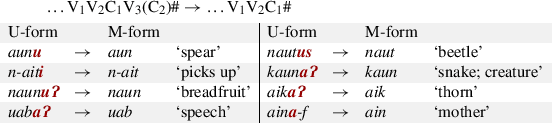

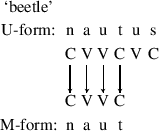

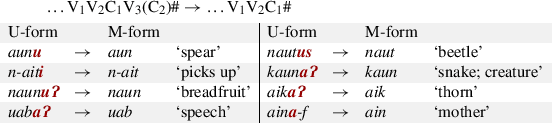

3.5 Complication 4: Vowel deletion

The final complication involves words which end in VVCV(C)# in the U-form; words with a phonetic diphthong. Such words derive their M-form by deletion of the final vowel as well as any final consonant. The surface relationship between the segments of the U-form and M-form of nautus [ˈnəw ʊs] → naut [ˈnə.ʊ

ʊs] → naut [ˈnə.ʊ ] ‘beetle’ is given in (49), with more examples given in (50) below.

] ‘beetle’ is given in (49), with more examples given in (50) below.

-

(49)

-

(50)

Sequences of three surface vowels do not occur in Amarasi. Thus, this vowel deletion can be analysed as resulting from phonological constraints of the language. If consonant-vowel metathesis were to occur, it would result in a disallowed sequence of three vowels which is resolved by vowel deletion.

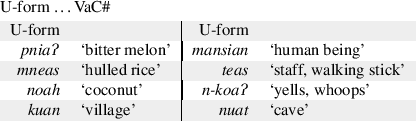

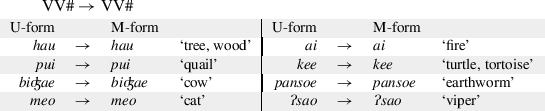

3.6 No change

Words which end in a vowel sequence do not have distinct U-forms and M-forms. Some examples are given in (51) below.

-

(51)

4 Unified analysis

A number of surface phonological operations occur in the formation of the M-form in Amarasi. Such phonological processes include: metathesis, consonant deletion and assimilation of /a/. Furthermore, metathesis itself can trigger further processes of consonant deletion, vowel deletion, and vowel height assimilation.

Which operations apply to a word is determined by the phonotactic structure of that word, as well as the quality of the vowels it contains. The different structures of the M-form are summarised in Table 4. With the exception of M-forms which end in a sequence of two identical vowels, all M-forms are phonetically disyllabic.

The M-form must be derived from the U-form as there is a large amount of ambiguity among M-forms. For instance, given an M-form with the shape V1V2C1#, we cannot predict whether the U-form will have a shape corresponding to any of shapes 1.–6. in Table 4. A concrete example is the form n-neen, which is the M-form of both n-nene ‘pushes’ and n-nena ‘hears’.

In this section I propose an analysis of the formation of all the different M-forms. I use an autosegmental model of phonology (Goldsmith 1976) and a rule based model of process morphology (Matthews 1974; Anderson 1992). Adopting these models allows me to formulate a single, unified analysis of the diverse processes which occur in the formation of Amarasi M-forms. In Sect. 5 I discuss alternate analyses which, while they can account for some of the data, cannot account for all the Amarasi data.

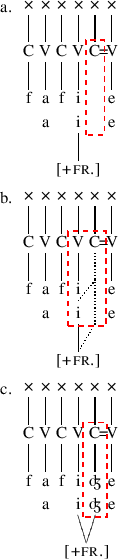

My analysis consists of a single process of metathesis at the CV tier and an associated morphemically conditioned process (/a/ assimilation). These processes, combined with an obligatory CVCVC foot structure and the general phonotactic constraints of Amarasi, generate all the different M-forms.

In my autosegmental diagrams in the following sections empty C-slots are occasionally ‘filled’ with ∅ in order to make it explicit that they behave identically to filled C-slots. This is a notational convenience. Similarly, the x-tier (or timing tier) is used as a notational device to illustrate clearly the effect of metathesis. Use of the x-tier should not be taken as a claim about its theoretical status.

4.1 The phonological rule: Obligatory CVCVC foot

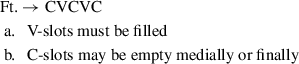

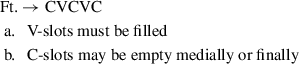

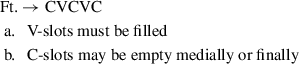

I posit that the Amarasi foot obligatorily has the structure CVCVC and that C-slots may be empty. This rule is given in (52) below. Extensive evidence (independent of metathesis) for the existence of empty C-slots in Amarasi is given in Appendix A.

-

(52)

Recall from Sect. 2.2 that metathesis in Amarasi is an inflectional process which marks a construct state in the syntax and a resolved state of affairs in the discourse. Under my analysis all words in Amarasi are subject to metathesis and thus this foot shape applies to all U-forms.

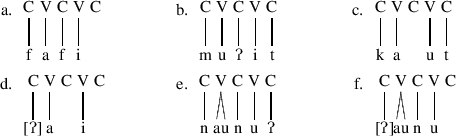

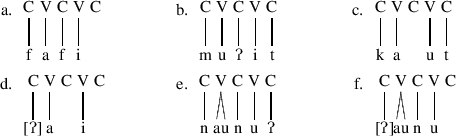

The structures of the words fafi ‘pig’, muʔit ‘animal’, kaut ‘papaya’, ai ‘fire’, nautus ‘beetle’ and aunu ‘spear’ under this analysis are given in (53) below.

-

(53)

The initial C-slots of the words ai ‘fire’ and aunu ‘spear’ in (53) have been filled with an automatic glottal stop, as is the case for all vowel initial words (Sect. 2.1.3). Such glottal stop insertion is the basis for specifying in the second part of rule (52) that C-slots may be empty only medially or finally; empty C-slots never occur initially. The reason initial C-slots must be filled is due to a requirement in Amarasi that morphemes begin with a consonant.

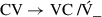

4.2 The morphological rule: Metathesis

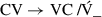

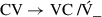

The single process required to generate M-forms is metathesis, given in (54) below, which states that a C-slot and a V-slot metathesise after a stressed V-slot. This rule is a morphological process, in the style of Anderson (1992).

-

(54)

In (54) I have included the phonological environment in which metathesis takes place; after a stressed V-slot. This is not the environment which triggers metathesis but rather the environment by which metathesis is constrained. I return to this point in Sect. 6.

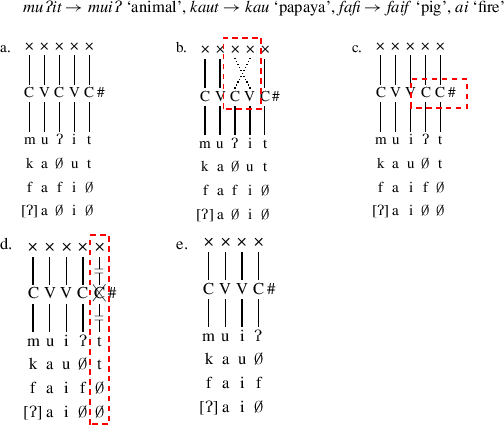

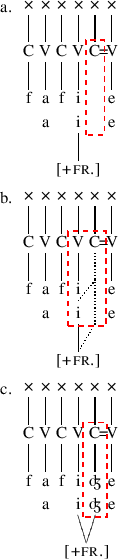

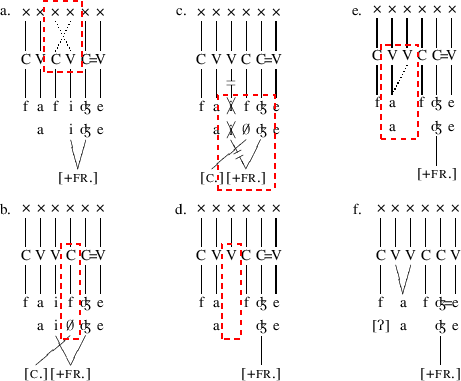

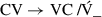

The operation of metathesis for the words muʔit ‘animal’, kaut ‘papaya’, fafi ‘pig’ and ai ‘fire’, is given in (55) below. (55a) shows the underlying U-form of each of these words. In (55b) metathesis of the penultimate C-slot and final V-slot takes place. This results in a disallowed word final cluster of two C-slots in (55c). To resolve this, the final C-slot is deleted in (55d) producing the M-forms in (55e).

-

(55)

4.2.1 Metathesis and mid vowel assimilation

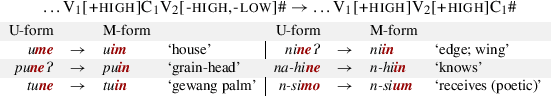

As discussed in Sect. 3.3.1, any final mid vowel assimilates to the height of a previous high vowel after metathesis. This vowel height assimilation is an instance of vowel harmony, arising out of the fact that that sequences of a high vowel and mid vowel are disallowed in Amarasi.Footnote 10

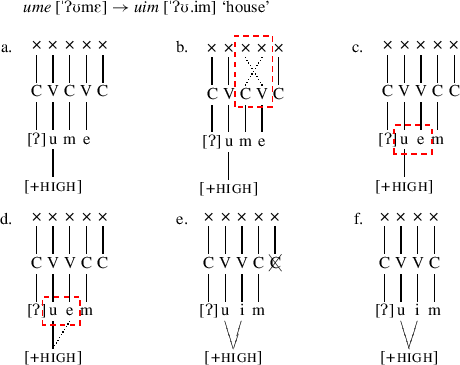

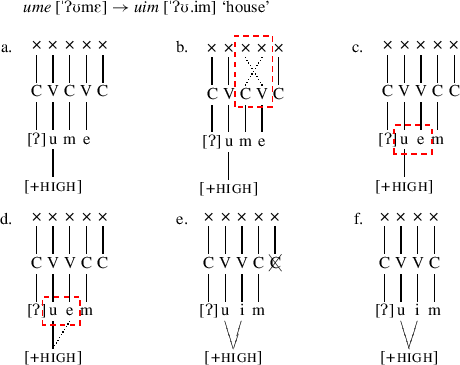

This process is illustrated for ume → uim ‘house’ in (56) below. After metathesis in (56b), the feature [+high] of the stressed vowel spreads in (56d) resulting in a sequence of two high vowels in (56e). Unless the [+high] feature of the penultimate vowel is analysed as privative we would also have to propose that the height features [-high, +mid] of the final vowel /e/ de-link (56d).

-

(56)

4.2.2 Metathesis and vowel deletion

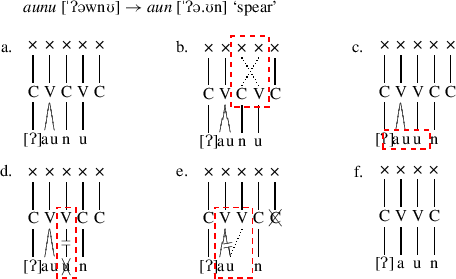

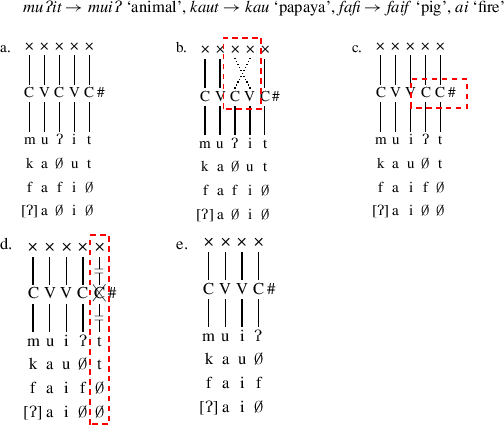

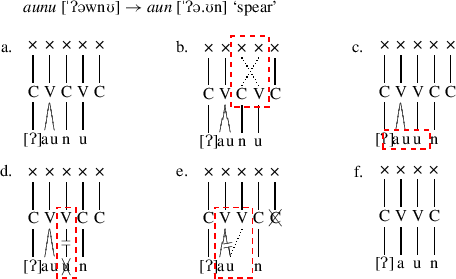

The vowel deletion seen in words with a phonetic diphthong, such as aunu [ˈʔəwnʊ] → aun [ˈʔə.ʊn] ‘spear’, results from metathesis and the fact that Amarasi does not allow sequences of three surface vowels. Recall from Sect. 2.1.2 that the first two vowels of words with a phonetic diphthong are associated to a single V-slot, as shown by the fact that stress falls on the antepenultimate vowel rather than the penultimate vowel.

The formation of the M-form for aunu [ˈʔəwnʊ] → aun [ˈʔə.ʊn] ‘spear’ is illustrated in (57) below. Metathesis in (57b) results in a surface sequence of three vowels in (57c); the first V-slot is associated to two vowels which are adjacent to another vowel associated to a single V-slot. As a result, the final vowel is deleted in (57d), with subsequent re-association of the adjacent vowel into the now empty V-slot in (57e). The final C-slot is also deleted yielding the final output shown in (57f).

-

(57)

Evidence that it is the final vowel and not the penultimate vowel which is deleted comes from the word n-aena ‘runs, flees’ with the M-form n-aen. If the second vowel were deleted after metathesis in words with an initial phonetic diphthong, n-aena ‘runs, flees’ would have the M-form *n-aan.Footnote 11

There are no other processes in Amarasi which create a sequence of three vowels within a morpheme. All other potential VVV sequences would occur across a morpheme boundary in which case consonants are inserted; a voiced obstruent morpheme finally (Sect. A.2), and a glottal stop morpheme initially (Sect. A.4, Edwards 2017:427f).

The derivation of the M-form for a word such as aunu [ˈʔəwnʊ] → aun [ˈʔə.ʊn] ‘spear’ is not significantly different to that of a word such as fanu [ˈfanʊ] → faun [ˈfa.ʊn] ‘eight’. In both circumstances the M-form is VVC final with each vowel the peak of its own syllable. The only difference is in the resolution of the disallowed sequence of three vowels for VVCV(C)# final words.

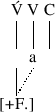

4.3 The morphemically conditioned rule: Assimilation of /a/

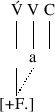

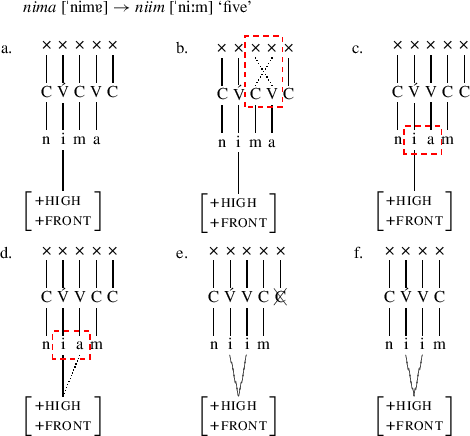

The morphological process of metathesis triggers assimilation of final /a/, as seen in examples such as nima → niim ‘five’. This rule is given as rule (58) below. This rule states that the features (represented by [+F.]) of the stressed vowel spread when immediately followed by /a/ and a filled C-slot.

-

(58)

This assimilation of /a/ is a derived environment effect. It is not dissimilar to umlaut in German plurals, in that both occur only in morphologically derived environments. In German, a floating autosegment triggers fronting of the root vowel only in morphologically derived environments, such as in plurals (Wiese 1996:181ff). In Amarasi /a/ assimilation only occurs in a morphologically derived environment: the M-form. (Used to mark a construct state or resolved state of affairs, see Sect. 2.2.)

The reason only /a/ assimilates in Amarasi can be explained by the fact that it is almost featureless.Footnote 12 Perhaps apart from the feature [+low], /a/ is not specified for front or back. This lack of features allows the features of the stressed vowel to spread when the V-slot to which /a/ is associated occurs immediately after it.

The formation nima → niim ‘five’ is given in (59) below. Metathesis occurs in (59b), resulting in the V-slot to which /a/ is associated occurring immediately after a stressed V-slot and before a filled C-slot in (59c). Thus, the features of the stressed vowel spread in (59d), creating a sequence of two identical vowels in (59e). The final C-slot is then deleted yielding the final output shown in (59f).

-

(59)

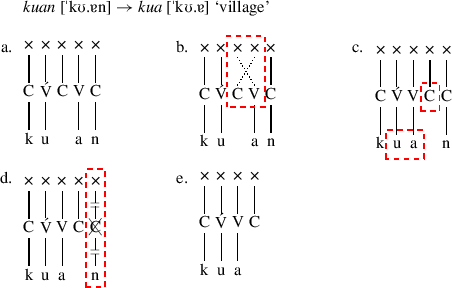

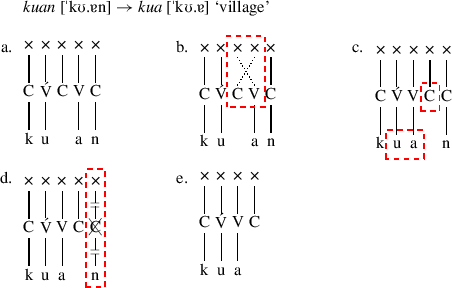

Under my analysis /a/ assimilation is triggered by the presence of the two immediately adjacent V-slots which occur in M-forms, as seen in (59c)–(59f). The lack of assimilation in U-forms such as kuan ‘village’ is simply explained by the fact that there is an intervening C-slot between the two vowels; ku_an. The environment necessary for the operation of rule (58) is not present.

The rule of /a/ assimilation in (58) only occurs before filled C-slots. That is, it does not occur in the M-form of words such as kuan → kua ‘village’. I analyse the lack of assimilation in such forms as being due to the lack of a following filled C-slot.

The formation of kuan → kua ‘village’ is given in (60) below. Metathesis at the CV tier occurs in (60b), resulting in the V-slot to which /a/ is associated occurring directly after the stressed V-slot. However, the following C-slot is empty. This means the environment under which /a/ assimilation occurs is not present. Thus, no assimilation takes place. The final C-slot is then deleted in (60d)–(60e).

-

(60)

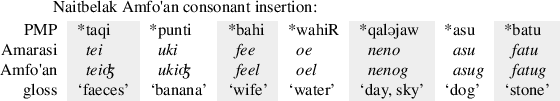

That /a/ is protected from assimilation by a following empty C-slot finds comparative support from Ro'is Amarasi (a different dialect to that which is the focus of this paper). Ro'is Amarasi has a process whereby any unstressed /a/ (optionally) assimilates to the quality of the preceding stressed vowel. Such assimilation occurs in the U-form of certain consonant final words. A number of examples are given in Table 5.

The assimilation of /a/ in Ro'is Amarasi final syllables only applies to words which end in a surface consonant; a filled C-slot. It does not occur in words end in a vowel; an empty C-slot. Two such examples are Amarasi na-tfeka and Ro'is Amarasi na-tfera *na-tfere ‘to decide’, as well as Amarasi ʔrim-rimaʔ Ro'is Amarasi rim-rima *rim-rimi ‘firefly’. In both these examples the Ro'is Amarasi forms are vowel final and under an analysis employing the obligatory CVCVC foot thus end in an empty C-slot.

4.4 Summary

In this section I have proposed a single unified analysis of the formation of the M-form from the U-form in Amarasi. This analysis is framed under an autosegmental model of phonology (Goldsmith 1976) and a rule based model of process morphology (Matthews 1974; Anderson 1992). My analysis consists of three rules: one phonological rule, one morphological rule, and one morphemically conditioned rule. These three rules are repeated in (61)–(63) below.

-

(61)

-

(62)

-

(63)

These three rules combined with the general phonotactic constraints of Amarasi are sufficient to account for formation of the M-forms. The general phonotactic constraints of Amarasi with which these rules interact are given below:

-

clusters of two C-slots are prohibited word finally

-

sequences of three surface vowels are prohibited

-

vowel sequences consisting of a high-vowel and mid-vowel are prohibited

This rule based analysis of Amarasi accounts for all of the data in a single consistent way. In the final section of this paper I consider some alternate analyses. While these analyses can account for some of the data Amarasi data they cannot account for all of the data.

5 Alternate approaches

In the final part of this paper I consider the ways alternate approaches would handle the Amarasi data. There are no existing proposals in the literature which can adequately handle all of the Amarasi data.

In Sect. 5.1 I consider whether an approach framed within prosodic morphology (McCarthy and Prince 1990, 1993/2001) can explain the Amarasi data. In particular, I consider whether the analysis of McCarthy (2000) for Rotuman metathesis or that of Heinz (2004) for Kwara’ae can be extended to Amarasi. While such analyses can explain a small amount of the Amarasi data, they cannot explain it all. Furthermore, because there is no consistent single prosodic structure present in Amarasi surface M-forms, an analysis framed within prosodic morphology does not seem appropriate.

In Sect. 5.2 I show that Amarasi metathesis cannot be analysed as phonologically conditioned as has been proposed for Rotuman (Hale and Kissock 1998; McCarthy 2000), Kwara’ae (Heinz 2004), and Luang (Taber and Taber 2015).

Finally, In Sect. 5.3 I show that it is typologically implausible to analyse the Amarasi data as a fundamentally concatenative process involving affixation of a CV melody to the segmental information of a word.

5.1 Prosodic morphology

One alternate approach to the data would be to analyse Amarasi metathesis within the framework of prosodic morphology. Such an analysis has been proposed by McCarthy (2000) for Rotuman metathesis. Similarly, Heinz (2004) proposes an analysis of synchronic metathesis in Kwara’ae which is compatible with a prosodic morphological approach. After a discussion of each of these analyses, I show that neither can be adapted and/or extended to the Amarasi data.

5.1.1 Rotuman

Rotuman has been described most comprehensively by Churchward (1940).Footnote 13 In Rotuman each word has two forms, first labelled by Churchward the ‘complete phase’ (≈ U-form) and the ‘incomplete’ phase (≈ M-form).

A variety of different processes are used to form the incomplete phase from the complete phase. These processes include: vowel deletion, metathesis, umlaut, or diphthongisation Which process applies is depends on the quality of the penultimate and final vowels of the complete phase, as well as whether the complete phase is VCV# final or VV# final. There are also a certain number of word shapes with no distinction between the two forms. Examples of each of these processes extracted from Churchward (1940) are given in Table 6 in standard IPA transcription.

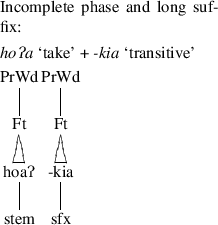

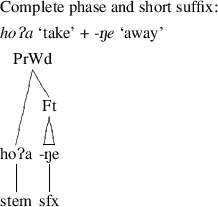

An analysis of the Rotuman data within the framework of prosodic morphology and Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993) is presented in McCarthy (2000). McCarthy (2000:159) bases his analysis on the observation that “The incomplete phase is identical to the complete phase, except that the final foot of the complete phase is realised as a monosyllabic foot in the incomplete phase.” Regarding words which form the complete phase via metathesis, such as hoʔa → hoaʔ ‘take’, McCarthy (2000) argues that the incomplete phase consists of a single syllable, as is consistent with more recent descriptions of Rotuman including Besnier (1987) and Vamarasi (2002).Footnote 14

Under McCarthy’s analysis Rotuman is a weight sensitive language. Because a (metathesised) monosyllable such as hoaʔ ‘take’ is consonant final, it has two morae and bears stress as expected for a heavy syllables in a weight sensitive language.

McCarthy (2000) also draws upon the observation by Hale and Kissock (1998) that in most cases the use of the two stems in Rotuman is conditioned by the number of syllables of a following suffix or enclitic. Suffixes and enclitics consisting of two or more syllables trigger the complete phase, while monosyllabic or non-syllabic suffixes and enclitics occur with a stem in the incomplete phase.Footnote 15

McCarthy (2000:156) then draws upon the principle of Foot Binarity, whereby feet are required to consist of a minimum of either two syllables or two morae. McCarthy proposes that polysyllabic suffixes and enclitics are prosodically external to the stem, as they are eligible to form independent feet. Non-syllabic and monosyllabic suffixes, on the other hand cannot form feet and are thus bound to the stem.

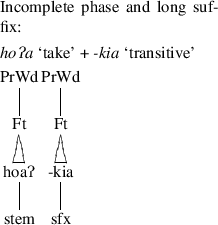

McCarthy (2000:163) represents forms like hoaʔ-kia ‘take-transitive’ with the structure given in (64). The stem of this form is in the incomplete phase (a heavy syllable consisting of two morae) with a polysyllabic suffix/enclitic attached. McCarthy represents forms like  ‘take-towards.third.person’ with the structure given in (65). The stem of this form is in the incomplete phase (a disyllable) with a monosyllabic suffix. In both these diagrams ‘PrWd’ stands for ‘prosodic word’; an independent prosodic unit.Footnote 16

‘take-towards.third.person’ with the structure given in (65). The stem of this form is in the incomplete phase (a disyllable) with a monosyllabic suffix. In both these diagrams ‘PrWd’ stands for ‘prosodic word’; an independent prosodic unit.Footnote 16

-

(64)

-

(65)

The constraint Align-Head-σ, which requires stressed syllables to be word final, is crucial in McCarthy’s analysis. This constraint regulates prosodic words. When a stem occurs with a long suffix, each prosodic word occurs in the incomplete phase. This means that both the stem and the suffix/enclitic in (64) would occur in the incomplete phase. When a stem occurs with a short suffix the whole prosodic word,—the stem combined with the suffix/enclitic—would occur in the incomplete phase.

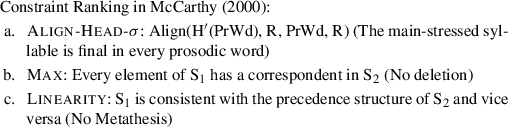

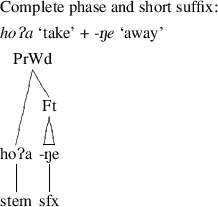

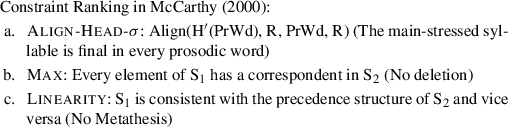

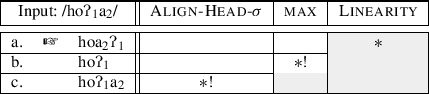

For Rotuman, the constraint Align-Head-σ and the constraint max (prohibiting deletion) are ranked more highly than the constraint Linearity (prohibiting metathesis). Each of these three constraints is given in (66) below.

-

(66)

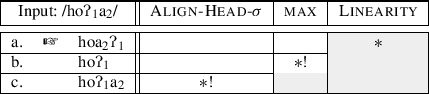

Metathesis occurs as it is “[…] the most faithful constraint mapping of a /…VCV/ input that still satisfies Align-Head-σ.” McCarthy (2000:174) gives an equivalent of the optimality table in (67) below.

-

(67)

Under McCarthy’s analysis Rotuman metathesis (along with other processes which form the incomplete phase) occurs in order to create final stressed syllables within the domain of the prosodic word. I refer the reader to McCarthy (2000) for a full analysis of the different phonological processes in Rotuman and the ways in which these are handled.

5.1.2 Kwara’ae

Metathesis in Kwara’ae has been described by Sohn (1980) and Heinz (2004, 2005). Blevins and Garrett (1998) also present previously unpublished data collected by Andrew Pawley and David Gegeo. In this section I summarise the description and analysis of Kwara’ae metathesis in Heinz (2004).

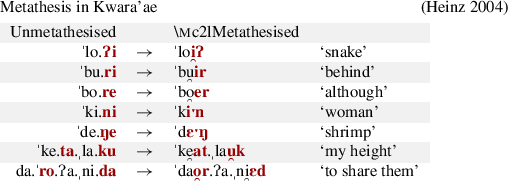

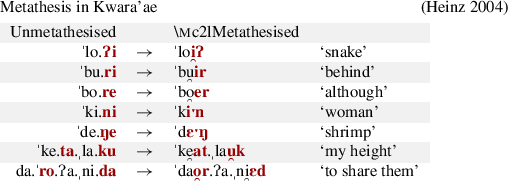

In Kwara’ae the metathesised form of words is the form of words used in everyday normal speech while the unmetathesised form is used in traditional songs, for clarification and when calling/yelling out. Some examples of metathesis in Kwara’ae are given in (68) below.

-

(68)

According to Heinz’s description, each Kwara’ae unmetathesised form in (68) contains one or more stressed syllables with a single vowel which are followed by an unstressed vowel. Each metathesised form contains stressed syllables, each of which is a heavy syllable containing either a vowel and glide or a long vowel.

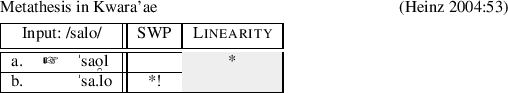

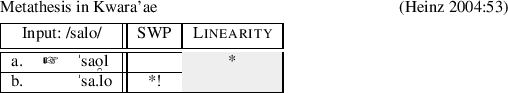

Based on this observation Heinz (2004) analyses metathesis in Kwara’ae as being conditioned by the placement of stress. His analysis is framed under Optimality Theory and is based on ranking the Stress to Weight Principle constraint (requiring stressed syllables to be heavy) more highly than the constraint of Linearity, which requires segments to occur in their underlying order. Given an underlying form such as /salo/ ‘sky’, the metathesised form with a heavy syllable consisting of a vowel and glide is selected rather than the unmetathesised form with two light syllables, as shown in the optimality table in (69) below

-

(69)

5.1.3 Amarasi

Although the analysis of McCarthy (2000) for Rotuman and the analysis of Heinz (2004) for Kwara’ae are different in several details, in each case metathesis is analysed as occurring in order to create a monosyllabic form which bears stress.

Whatever merits these analyses may have for Rotuman or Kwara’ae, they cannot be extended to describe the Amarasi data. This is because in most cases the stress and number of syllables of a U-form and M-form are identical.

This is true of forms with different penultimate and final vowels which undergo metathesis, such as hitu [ˈhi. ʊ] → hiut [ˈhi.ʊ

ʊ] → hiut [ˈhi.ʊ ] ‘seven’. It is true of words which undergo metathesis and deletion of a final consonant, such as muʔit [ˈmʊ.ʔi

] ‘seven’. It is true of words which undergo metathesis and deletion of a final consonant, such as muʔit [ˈmʊ.ʔi ] → muiʔ [ˈmʊ.iʔ] ‘animal’. It is also true of words which undergo deletion of a final consonant such as kuan [ˈkʊ.ɐn] → kua [ˈkʊ.ɐ] ‘village’.Footnote 17

] → muiʔ [ˈmʊ.iʔ] ‘animal’. It is also true of words which undergo deletion of a final consonant such as kuan [ˈkʊ.ɐn] → kua [ˈkʊ.ɐ] ‘village’.Footnote 17

The only cases in which such an analysis could be successfully applied are those in which the M-form is, arguably, a reduced form. This includes words in which the penultimate and final vowel are identical, such as fini [ˈfɪ.ni] → fiin [ˈfiːn] ‘seed’, or those in which assimilation of /a/ occurs, such as nima [ˈni.mɐ] → niim [ˈniːm] ‘five’. It also perhaps includes words with an initial phonetic diphthong, such as nautus [ˈnəw. ʊs] → naut [ˈnə.ʊ

ʊs] → naut [ˈnə.ʊ ] ‘beetle’.

] ‘beetle’.

In cases in which the M-form has a final sequence of two identical vowels, such as fini [ˈfɪ.ni] → fiin [ˈfiːn] ‘seed’, there is a reduction in the number of phonetic syllables, with a resultant change in stress from a light syllable to a heavy syllable. In such instances alone an analysis along the lines of McCarthy (2000) or Heinz (2004) in which metathesis occurs to create a heavy stressed syllable could be proposed. However, given the evidence for treating phonetically long vowels as a sequence of two identical vowels (Sect. 2.1.1), and the fact that Amarasi is otherwise not a weight sensitive language (Sect. 2.1.2), this analysis is not consistent with other facts of the language.

Not only does such an analysis contradict other facts of Amarasi, but it also cannot account for all the data, as the M-form of words such as hitu [ˈhi ʊ] → hiut [ˈhi.ʊ

ʊ] → hiut [ˈhi.ʊ ] ‘seven’ simply does not contain a stressed heavy syllable. Therefore, neither of the analyses proposed by McCarthy (2000) or Heinz (2004) can be explain all the Amarasi data.

] ‘seven’ simply does not contain a stressed heavy syllable. Therefore, neither of the analyses proposed by McCarthy (2000) or Heinz (2004) can be explain all the Amarasi data.

Furthermore, it is not at all clear that any analysis framed within prosodic morphology could account for the Amarasi data.

One approach, broadly in-line with the notion that consonant-vowel metathesis is a reduction strategy, would be to propose that the M-forms occur in order to create a phonetically shorter form. An M-form with a vowel sequence such as hiut [ˈhi.ʊ ] ‘seven’ is usually, though not always, phonetically shorter than the U-form hitu [ˈhi

] ‘seven’ is usually, though not always, phonetically shorter than the U-form hitu [ˈhi ʊ] in which the two vowels are separated by a consonant.Footnote 18 Apart from the fact that the phonetic length of a word in Amarasi is primarily determined by speech speed, sentence stress, and pragmatics rather than the phonotactic shape of a word, this approach would leave unexplained forms in which the U-form and M-form both have a vowel sequence, such as kuan [ˈkʊ.ɐn] → kua [ˈkʊ.ɐ] ‘village’.

ʊ] in which the two vowels are separated by a consonant.Footnote 18 Apart from the fact that the phonetic length of a word in Amarasi is primarily determined by speech speed, sentence stress, and pragmatics rather than the phonotactic shape of a word, this approach would leave unexplained forms in which the U-form and M-form both have a vowel sequence, such as kuan [ˈkʊ.ɐn] → kua [ˈkʊ.ɐ] ‘village’.

Another possibility would be to propose that there is a requirement that M-forms occur in order to create consonant final forms. Such a proposal does not explain why VVC# U-forms such as kuan [ˈkʊ.ɐn] → kua [ˈkʊ.ɐ] ‘village’ delete their final consonant to form a M-form, nor why already consonant final U-forms such as [ˈmʊ.ʔi ] → muiʔ [ˈmʊ.iʔ] ‘animal’ undergo metathesis in the M-form.

] → muiʔ [ˈmʊ.iʔ] ‘animal’ undergo metathesis in the M-form.

The diversity in the surface prosodic structures of M-forms in Amarasi confounds an analysis framed within prosodic morphology. While in Rotuman there is a comparable diversity in forms, nearly all instances of the incomplete phase have been analysed as bi-moraic monosyllables, thus an analysis framed within prosodic morphology is successful.

A prosodic morphology approach to the Amarasi data encounters serious challenges which cannot obviously be overcome. Instead, by adopting a process based model of morphology and an obligatory CVCVC foot structure for U-forms, the different processes in the formation of the Amarasi M-form can be explained with a single process of metathesis and a single morphemically conditioned rule of /a/ assimilation. This analysis accounts for the formation of all Amarasi M-forms in a simple, consistent, unified way.

Finally, regarding Optimality Theory, which is utilised in the analyses of McCarthy (2000) and Heinz (2004), the high level of opacity/ambiguity in the formation of M-forms—including at least one derived environment effect (Sect. 3.3.2)—indicates that standard Optimality Theory would not fare particularly well in Amarasi. This is one of the reasons I have not employed it in this paper.

5.2 Phonologically conditioned metathesis

Another possible approach to the Amarasi data would be to analyse metathesis as phonologically conditioned. This is, in fact, part of the analysis of Rotuman given by McCarthy (2000:168) who explicitly rejects the idea that there is a metathesis morpheme and states: “[…] earlier accounts of the phase difference are inadequate empirically, since it does not make sense to talk of a phase morpheme or template.”Footnote 19

Another language with synchronic consonant-vowel metathesis which has been analysed as phonologically conditioned is Luang in the Timor region (Taber and Taber 2015). For Luang, Taber and Taber (2015:24) propose that metathesis is one of several phonological processes which operates to join adjacent words into a single rhythm unit with only one stressed syllable.

Whatever the case may be for Rotuman or Luang, metathesis in Amarasi cannot be reduced to a phonologically conditioned process. As discussed in Sect. 2.2, metathesis in Amarasi is the only phonological marking of certain syntactic and/or discourse structures.

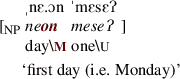

Amarasi nouns followed by cardinal and ordinal numerals provide the clearest demonstration that Amarasi metathesis is not phonologically conditioned. When followed by a cardinal number, nouns occur in the U-form. However, when followed by an ordinal number, nouns occur in the M-form. Examples are given in Table 7, which shows the noun neno ‘day’ followed by cardinal and ordinal numbers 1–6.Footnote 20

There is no phonetic difference between each kind of phrase, with the exception of the metathesis of the noun and, where applicable, the addition of the glottal stop forming ordinal numbers. In every phrase the noun has two syllables and stress falls on the penultimate vowel of the numeral. Compare especially the phrase neno meseʔ ‘a single day’ with that of neon meseʔ ‘first day (Monday)’, in which the only difference is in the metathesis of the noun.

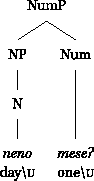

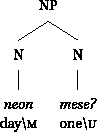

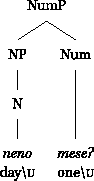

Instead, the M-form marks that these phrases have different syntactic structures. Ordinal numbers occur within the noun phrase while cardinal numbers occur outside of the noun phrase as the head of a number phrase. The different syntactic structures of the phrases neno meseʔ ‘one day’ and neon meseʔ ‘Monday’ are shown in (70) and (71) below.

-

(70)

-

(71)

Such data rule out an analysis of Amarasi metathesis as phonologically conditioned, unless we are willing to posit that different syntactic structures are associated with different abstract phonological structures—phonological structures with no phonological realisation.

5.3 Affixation of consonant-vowel melody

A final possible analysis of Amarasi metathesis would be to analyse it under an item and arrangement model of morphology in which the consonant-vowel template itself is a kind of affix which attaches to the segmental information of a word. This is the analysis proposed by Stonham (1994:160f) for Rotuman metathesis and would be similar to the analysis of Arabic morphology in McCarthy (1981).

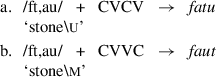

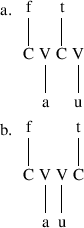

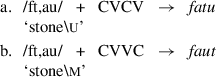

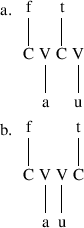

Under such an analysis, each consonant of an Amarasi word would be ordered with respect to each other consonant and each vowel would be ordered with respect to each other vowel, but consonants and vowels would not be ordered with respect to one another. an Amarasi word such as fatu ~ faut ‘stone’ could then be represented as either /ft,au/ or /au,ft/. This segmental information then combines with the appropriate consonant-vowel melody. This is shown in (72) below which makes explicit the concatenative nature of this analysis, and in (73) with autosegmental notation. Examples (72a) and (73a) show U-forms and examples (72b) and (73b) show M-forms.

-

(72)

-

(73)

An analysis of Amarasi metathesis as a result of affixation with different consonant-vowel melodies is possible. Under such an analysis, the selection of the appropriate melody would be determined by morphosyntactic criteria.

While a concatenative analysis accurately describes the data, there are two ways in which the process-based analysis adopted in this paper better fits the Amarasi data.

Firstly, it is always possible to derive surface M-forms from U-forms, but not visa-versa. Under a concatenative analysis, we simply have two affixes CVCV for the U-form and CVVC for the M-form, with no clear relationship between the two, and no apparent explanation for why one form predicts the latter but not visa-versa. Under a process-based analysis this is simply because M-forms are formed by CV metathesis from U-forms.

Secondly, the affixal approach to metathesis is completely unconstrained. Under such an analysis there is no clear reason why the M-form melody has the shape CVVC instead of any other arbitrary shape.Footnote 21 On the other hand, adopting an obligatory CVCVC foot structure for U-forms with a single rule of CV metathesis after stressed vowels typologically fits with observations of cross linguistic patterns of CV metathesis in which such metathesis affects syllables immediately before or after the stressed syllable.Footnote 22

An obvious defence of the concatenative analysis would be the observation that there are languages in which all sorts of consonant-vowel melodies occur, such as Arabic or Miwok. However, there are sound typological and areal reasons for positing a process-based metathesis analysis for the Amarasi data rather than a concatenative CV-melodic analysis: languages with independent CV-melodies are not found in the Timor region, while there are many languages in this region which have consonant-vowel metathesis; whether phonologically conditioned, morphemically conditioned or purely morphological.

A map of the languages of the Timor region for which synchronic consonant-vowel metathesis has been reported is given in Fig. 3.Footnote 23 The reasons for such a high concentration of languages with consonant-vowel metathesis in this region deserves further investigation.

6 Conclusion

In this paper I presented data from Amarasi, a language in which each word has two forms which are used in different morpho-syntactic environments: the U-form and the M-form. A number of different phonological processes occur in the formation of the M-form including: consonant-vowel metathesis, consonant deletion and two different kinds of vowel assimilation.

All these processes can be explained under an autosegmental model of phonology and a process based model of morphology by positing that Amarasi has an obligatory CVCVC foot structure in which C-slots can be empty, a single morphological rule of consonant vowel metathesis at the CV-tier after stressed V-slots, and a single morphemically conditioned rule of /a/ assimilation.

I also considered alternate approaches to the data including other analyses of processes of consonant-vowel metathesis. An analysis of Amarasi metathesis within prosodic morphology which parallels that of McCarthy (2000) for Rotuman or Heinz (2004) for Kwara’ae is not possible as Amarasi is not a weight sensitive language and metathesis does not result in a reduction of the number of syllables. Furthermore, the diversity of prosodic structures found in Amarasi M-forms are likely to confound a unified analysis of Amarasi M-forms within prosodic morphology.

I also showed that Amarasi metathesis cannot be analysed as phonologically conditioned and that a concatenative analysis of Amarasi M-forms is typologically highly implausible and does not explain why U-forms predict M-forms but not visa-versa.

Amarasi therefore presents a true case of morphological metathesis. The existence of languages with morphological metathesis must be taken seriously and must inform the development of morphological theory. In this respect, I echo the sentiment of Thompson and Terry Thompson (1969:217) in their discussion of morphological metathesis in Klallam.

Given the existence of true cases of morphological metathesis, the next step is a careful investigation of both the form and function of reported cases of metathesis. Doing so is a fruitful way in which we can enrich and further refine our understanding of both morphology and phonology.

Notes

The labels ‘U-form’ and ‘M-form’ should be taken as the names of two different morphological forms, similar to the terms ‘complete phase’ and ‘incomplete phase’ coined by Churchward (1940) in his discussion of Rotuman metathesis. The labels ‘U-form’ and ‘M-form’ can be taken as formal or functional abbreviations. Formally, the M-form is the

etathesised form while the U-form is the

etathesised form while the U-form is the  nmetathesised or

nmetathesised or  nderlying form. Functionally, in the syntax M-forms mark

nderlying form. Functionally, in the syntax M-forms mark  odification and in the discourse U-forms mark

odification and in the discourse U-forms mark  nresolved events or situations.

nresolved events or situations.Current work indicates that Tais Nonof is a label for the speech of those originally living along the coast of the Amarasi area, this includes people whose speech is mst similar to Kotos Amarasi and those whose speech is most similar to Ro'is Amarasi. From a comparative perspective, Kotos Amarasi is phonologically more closely related to other varieties of Uab Meto than it is to Ro'is Amarasi (Edwards 2016c). The term 'Hero' is applied by Amarasi speakers to Helong; a distinct people group with a distinct language, but this term may also be a distinct variety of Uab Meto in the Amarasi area.

The consonant /t/ is dental [

]. The mid vowels /e/ and /o/ are mid-low [ε] and [ɔ], respectively. They are usually raised to mid-high [e] and [o] before other high vowels. The voiced obstruents are realised as either plosives [b ʤ gw] or fricatives [β Ʒ ɣw].

]. The mid vowels /e/ and /o/ are mid-low [ε] and [ɔ], respectively. They are usually raised to mid-high [e] and [o] before other high vowels. The voiced obstruents are realised as either plosives [b ʤ gw] or fricatives [β Ʒ ɣw].Culturally, betel-nut is chewed by all parties before any social gathering. Thus, ma-pua-ʔ ‘having betel-nut’ is used metaphorically to mean ‘preface, prelude, introduction’.

I draw a distinction between ‘lexical roots/words’ and ‘functors’ (Zorc 1978; Grimes 1991:85ff). Functors include words which typically have grammatical uses, such as relativisers, demonstratives, topic markers and pronouns. Lexical words/roots typically refer to events, states, properties and things.

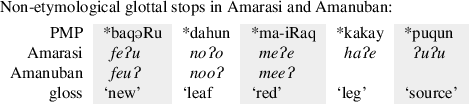

It is probably the case that nearly all roots greater than two syllables are historic phrases or affix-stem combinations. There are a handful of roots greater than four syllables in my current database. All such roots can be identified as historic phrases. One such example is aiʤonuus ‘a kind of herb’ which is historically composed of aiʤoʔo ‘Casuarina tree’ and nuus which does not occur independently in Amarasi but is attested in other Uab Meto varieties with the meaning ‘blue’.

The only instances in which a consonant cluster occurs in a position other than immediately before the penultimate vowel of the foot are the three words ʔbakʔuru ‘Indian Mulberry’, ʔbo-boe ‘heron, stork’ and ʔbak-bakan ‘monitor lizard’. Of these, the last two are instances of frozen reduplication from disyllabic roots.

The M-form n-maet ‘3-die’ in (35) is formed from the root √mate and the M-form n-hain ‘3-dig’ in (36) is formed from the root √hani.

The only exceptions are words with identical penultimate and final vowels such as fini [ˈfini] → fiin [ˈfiːn] ‘seed’, in which case there is a reduction in the number of phonetic syllables and thus arguably also in the placement of stress. Note however, as discussed in Sect. 2.1.1, there is no basis for analysing such words differently from words with different penultimate and final vowels.

Amarasi exhibits one other instance of vowel harmony involving height. This is raising of the mid-vowels to mid-high before high vowels. Thus, mid-vowels /e/ and /o/ are usually realised as mid-low. Three examples are kofaʔ → [ˈk

fɐ] ‘canoe’, mneas → [ˈ

fɐ] ‘canoe’, mneas → [ˈ

as] ‘hulled rice’, and seo → [ˈs

as] ‘hulled rice’, and seo → [ˈs  ] ‘nine’. However, before the high vowels /i/ or /u/, mid vowels are usually raised to mid-high. Examples include n-reruʔ → [ˈndɾ

] ‘nine’. However, before the high vowels /i/ or /u/, mid vowels are usually raised to mid-high. Examples include n-reruʔ → [ˈndɾ  ɾʊʔ] ‘sleepy’, betiʔ → [ˈβ

ɾʊʔ] ‘sleepy’, betiʔ → [ˈβ tiʔ] ‘fried’, koʔu → [ˈk

tiʔ] ‘fried’, koʔu → [ˈk ʔʊ] ‘big’, and ori-f → [ˈʔ

ʔʊ] ‘big’, and ori-f → [ˈʔ  ɾɪf] ‘younger same sex sibling’.

ɾɪf] ‘younger same sex sibling’.The stem n-aena ‘runs, flees’ is the only stem in my current corpus with an initial phonetic diphthong in which the penultimate and final vowels are not identical and which does not end in a consonant. (Recall from Sect. 3.3.2 that /a/ assimilates after metathesis when followed by a consonant). Thus, it is the only stem which shows that it must be the third vowel and not the second vowel which is deleted.

In addition to Churchward (1940), both Besnier (1987) and Vamarasi (2002) also present descriptions of Rotuman based on their own fieldwork. Each of these three descriptions differs in details. This may be partly because the authors worked with different speakers at different times and may also be partly because they use different language/terminology to describe the same phenomena. In this section I use Churchward (1940) as the basis for my discussion, as this is also the basis for most subsequent discussion of Rotuman.

The proposal that the incomplete phase was monosyllabic when Churchward (1940) conducted his fieldwork is far from certain. Churchward (1940:86) states that “[T]he stress seems to be levelled out, so to speak, in the inc[omplete] phase. Thus: fora becomes foar, which is pronounced almost, though perhaps not quite, as one syllable, the stress being evenly distributed …” This statement is ambiguous. While McCarthy (2000) takes it to suggest the incomplete phase is a monosyllabic word, it can also be taken to mean that the incomplete phase is shorter in phonetic length even though it remains two syllables.

As noted by McCarthy (2000:162), Hale and Kissock (1998) identify two zero suffixes which occur with the complete phase and one monosyllabic suffix which occurs with the incomplete phase. Nonetheless, McCarthy (2000) does not offer any explanation for their aberrant behaviour beyond the analysis of Hale and Kissock (1998) in which these suffixes are actually moraic.

McCarthy (2000) uses different examples to illustrate the prosodic structures of the complete and incomplete phase of words. I have selected different examples in order to illustrate clearly the difference between metathesised and unmetathesised forms.

It is also worth noting that while words which end in VV#, such as ai [ʔa.i] ‘fire’, do not have distinct M-forms and U-forms in Amarasi, the prosodic structure of such a word is identical when it occurs in either a U-form or M-form environment (see Sect. 2.2 for a summary of the use of each form).

That the total length of a vowel sequence is usually shorter than the combined length of two vowels separated by a consonant is confirmed by an instrumental phonetic study. I marked vowels in Praat in three recorded texts from a single speaker and extracted their lengths with a script. (Words with a distinctive pause intonation were discarded.) This resulted in 255 measurements of both the vowels in forms such as hitu ‘seven’ (That is, the measurements of 510 vowels with the length of the penultimate and final vowels summed.) and 243 lengths of vowel sequences in M-forms such as hiut ‘seven’. The average length of two vowels separated by a consonant was 0.17 seconds and the average length of a vowel sequence was 0.13 seconds. A two tailed t-test showed that this difference was statistically significant (p>0.001). The lengths of 385 vowel sequences in U-forms such as kuan ‘village’ were also extracted and had an average length of 0.12 seconds. A two tailed t-test showed that the difference between vowel sequences in M-forms and U-forms is probably not statistically significant (p = 0.11).

That McCarthy (2000) explicitly rejects the notion of a “phase morpheme” is surprising given that Churchward (1940) gives many examples in which the use of the complete phase or incomplete phase is the only marker of a semantic difference. It can be used to mark a definite/indefinite distinction as in the pair famori ʔea ‘The people say.’ and famør ʔea ‘Some people say.’ (Churchward 1940:15). It can also be used to mark question answer pairs as in ʔe una ‘In the middle, did you say?’ ʔe uan ‘In the middle.’ (Churchward 1940:95). McCarthy (2000) does not offer any analysis of such uses of the incomplete/complete phase beyond mentioning that Hale and Kissock (1998) analysed such forms as taking zero suffixes which bear moraic weight.

The ordinal numbers in 7 are those used for counting days and months, and are derived from the cardinal numbers with the addition of a glottal stop as a suffix or infix.

The language-specific phonotactic structures of Amarasi would be one constraining factor.

Blevins and Garrett (1998) identify two kinds of CV metathesis for which I have further identified instances in which such metathesis is a morphological process. Firstly, there is compensatory metathesis in which metathesis develops through the weakening of unstressed syllables either before or after stressed vowels. This is the kind of metathesis found in Amarasi. Secondly, there is pseudo-metathesis in which metathesis develops through epenthesis and apocope, in which case metathesis is usually anchored to the left or right edge of a word. Pseudo-metathesis is one of the kinds of metathesis found in Luang (Taber and Taber 2015) and Leti (van Engelenhoven 1996, 2004).

Fig. 3 is based on information in Schapper (2015:135ff) as well as information provided by Charles Grimes (p.c. March 2015) and David Gil (p.c. December 2014). In this map ‘synchronic metathesis’ is used for instances of consonant-vowel metathesis which are phonologically conditioned, morphemically conditioned, or for which the data is currently ambiguous.

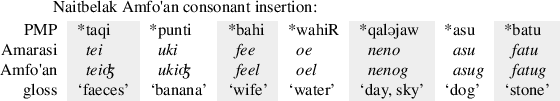

A similar Naitbelak Amfo'an example is agoel ‘rattan’ which can be compared with Fatule'u ual and Molo ue ‘rattan’.

References

Anderson, S. (1992). A-morphous morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Besnier, N. (1987). An autosegmental approach to metathesis in Rotuman. Lingua, 73, 201–223.

Blevins, J., & Garrett, A. (1998). The origins of consonant-vowel metathesis. Language, 74, 508–556.

Blust, R., & Trussel, S. ongoing. Austronesian comparative dictionary. http://www.trussel2.com/ACD/.

Churchward, C.M. (1940). Rotuman grammar and dictionary. Sydney: Methodist church of Australasia, Department of overseas missions.

Clements, G., & Keyser, S. (1983). CV phonology: a generative theory of the syllable. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs: Vol. 9. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Durand, J. (1990). Generative and non-linear phonology. London: Longman.

Edwards, O. (2016a). Amarasi. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 46, 113–125.

Edwards, O. (2016b). Metathesis and unmetathesis: Parallelism and complementarity in Amarasi, Timor. Doctoral Dissertation, The Australian National University. http://hdl.handle.net/1885/114481.

Edwards, O. (2016c). Parallel sound correspondences in Uab Meto. Oceanic Linguistics, 55, 52–86. http://hdl.handle.net/1885/108661.

Edwards, O. (2017). Epenthetic and contrastive glottal stops in Amarasi. Oceanic Linguistics, 56, 415–434.

van Engelenhoven, A. (1996). Metathesis and the quest for definiteness in the Leti of Tutukei (East-Indonesia). In H. Steinhauer (Ed.), Papers in Austronesian linguistics, Canberra: Pacifc Linguistics: Vol. A-84. (pp. 207–15).

van Engelenhoven, A. (2004). Leti, a language of Southwest Maluku. Leiden: KITLV Press.

Goldsmith, J. (1976). Autosegmental phonology. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Grimes, C. E. (1991). A grammar of Buru. Doctoral dissertation, The Australian National University.

Hale, M., & Kissock, M. (1998). The phonology-syntax interface in Rotuman. In M. Pearson (Ed.), Recent papers in Austronesian linguistics: Proceedings of the third and fourth meetings of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA) (pp. 115–128). Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Hayes, B. (1994). Metrical stress theory. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Heinz, J. (2004). CV metathesis in Kwara’ae. Master’s thesis, University of California.

Heinz, J. (2005). Optional partial metathesis in Kwara’ae. In J. Heinz & D. Ntelitheos (Eds.), Proceedings of the twelfth annual conference of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA): Vol. 12. pp. 91–102). UCLA Working Papers in Linguistics, Los Angeles: UCLA.

Jonker, J. C. G. (1908). Rottineesch-hollandsch woordenboek. Leiden: Brill.

Kenstowicz, M., & Kisseberth, C. (1977). Topics in phonological theory. New York: Academic Press.

Kiparsky, P. (1973). Phonological representations. In O. Fujimura (Ed.), Three dimensions of linguistic theory (pp. 1–136). Tokyo: TEC.