Abstract

This paper demonstrates that the person-number hierarchy effects in the Agent-Focus construction in Kichean languages of the Mayan family such as Kaqchikel, K’iche’, and Tz’utujil can be attributed to the general mechanism governing morphological realization of person and number features, once an appropriate characterization of relevant agreement markers is given. In other words, this account only relies on the minimal theoretical machinery needed for a description of individual languages, unlike previous analyses. The binary nature of person and number features plays a crucial role in the proposed account. It is also suggested that the impossibility of pairing a non-3rd person subject with a non-3rd person object in the Agent-Focus construction is due to the [+participant]-targeting application of the Obligatory Contour Principle. Furthermore, a novel pan-Mayan characterization of Agent-Focus is proposed to capture variation concerning the alternation between Agent-Focus and the plain transitive marking in the context of the Obligatory Contour Principle violation. The new characterization of AF also enables us to capture the rather exceptional form of the Agent-Focus construction in Yucatec. The overall framework is thus shown to have validity that extends beyond the Kichean group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Kaqchikel is unusual among Mayan languages, which are generally verb-initial, in preferring the SVO order in declaratives, unlike K’iche’ and Tz’utujil. The presence of the focus marker, therefore, is an important indicator of A-bar extraction of the subject. See England (1991) for comments on the Mayan word order from a historical perspective.

The fact that the AF construction displays only an absolutive marker is guaranteed by an separate constraint higher than Max(+foc), not indicated in (19). The same assumption is made for (16).

By adopting the ranking Max(+foc) ≫ Max(pers) ≫ Max(+pl) for Tz’utujil, Stiebels leaves the person restriction in this language unexplained. Examples like (ia, b) and their respective agreement marking alternatives are incorrectly allowed as tied optimal outputs, as the reader can easily verify.

-

(i)

Tz’utujil will be taken up again in Sect. 5, where a more fundamental problem for an Optimality-Theoretic approach in general is pointed out.

-

(i)

(20) does not belong to a family of ranked constraints.

Though Preminger does not comment on K’iche’ and Tz’utujil, the systematic correspondence between non-3rd person absolutive markers and their strong pronoun counterparts holds in these languages as well. Larsen (1987:38) notes that the absolutive markers and their strong pronoun counterparts in K’iche’ are identical except in the 3rd person. Dayley (1985b:62) observes that in Tz’utujil, the 1st and 2nd person strong pronouns are reduplicated forms of the corresponding absolutive markers, while the 3rd person strong pronouns are not.

There are instances where the doubled original argument is null. In that case, clitic doubling may be a misnomer, but I will gloss over this terminological point.

Under Preminger’s theory, failure of agreement is tolerated. In fact, this is a major thesis of Preminger (2014).

This necessitates special provisions for split ergativity. In fact, the appearance of ergative marking in a restricted class of intransitive clauses is often attributed to the presence of nominalized structure. Crucially, in the nominal domain, the ergative series is employed for possessor marking, as a pan-Mayan property (Larsen and Norman 1979). See Coon (2016) and the references cited there.

Watanabe (2013) also provides evidence for the binarity of the person system with the clusivity distinction.

To the extent that the dropping of the final consonant of (29a) and (29c), as indicated in (4), is due to an independent morphophonological process (Preminger 2014:24), it need not be mentioned in (29).

Incidentally, from the impossibility of 1st person plural in (9b) and (10), it can be seen that fusion of the two matrices does not take place. For a recent discussion of the Fusion operation, see Embick (2010).

The absolutive series of K’iche’ and Tz’utujil can be characterized analogously. The same account, therefore, will apply to these languages as well. See England (2011) for plural marking of common nouns in K’iche’, which recruits the 3rd person plural absolutive marker.

The ultimate choice between (29a, b) and (40a, b) should be relegated to a theory governing the feature specification of Vocabulary items, which does not yet exist, as far as I am aware. It goes beyond the scope of this article to provide one.

Identity avoidance in morphology has traditionally been given the name of haplology, which is often used to describe omission of a phonologically identical morphological piece (Menn and McWhinney 1984; Stemberger 1981). Plag (1998) and Yip (1998) point to the OCP as the underlying principle, making it possible to refer to features as relevant players.

In this connection, recall also from the discussion at the end of Sect. 3 cases of the PCC phenomena in Romance where the combination of 1st person and 2nd person is allowed.

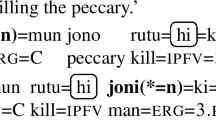

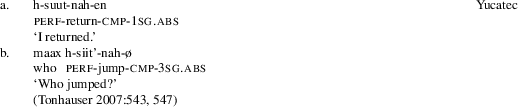

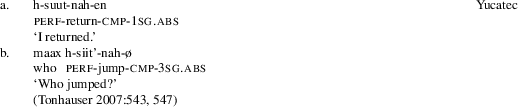

Stiebels (2006:553) treats the Yucatec AF construction as derived from morphological intransitivization, but this is not correct. Intransitive clauses have a preverbal mood/aspect marker, whether the subject extraction takes place or not, as shown in (i).

-

(i)

Stiebels does not account for these important details. See Bohnemeyer (2009), Gutiérrez-Bravo and Monforte (2011), Norcliffe (2009), and Tonhauser (2007) for further discussion of AF in Yucatec.

-

(i)

According to Bergqvist (2007), Lacandon also uses AF for transitive subject extraction, though the language has been classified as lacking it (Coon et al. 2014). Bergqvist claims that the Lacandon AF construction is not subject to any person restriction. Since Lacandon places the ergative marker preverbally and the absolutive marker postverbally as in Yucatec, the absence of a person restriction in the Lacandon AF construction strengthens the case.

The tentative suggestion offered by Coon et al. (2014: 224) for Q’anjob’al, which behaves in the same way in the relevant respects as Popti’, is also untenable, since they resort to the possibility that focused 1st and 2nd person subjects are base-generated in a clause-peripheral position, unlike focused 3rd person subjects. It remains to be accounted for why focus movement of 1st and 2nd person subjects is blocked.

The proposal by Assmann et al. (2015) is silent about how the person restriction in languages like Popti’ and Q’anjob’al and the hierarchy effects in languages like Kaqchikel are to be explained.

Recall from note 4 that the ranking Max(+foc) ≫ Max(pers) ≫ Max(+pl), adopted by Stiebels, makes an incorrect prediction. (54b) is the well-formed alternative to (ia) of note 4.

A possible way out for an Optimality-Theoretic approach might be to say that oblique marking is not a matter of input but of output. It remains to be seen how that analytical path will lead to a workable solution, though.

This way of handling inert agreement features may be regarded as an alternative to Arregi and Nevins’ (2012) two-step model, which uses the postsyntactic operation of Agree-Copy to make available for morphological realization the ϕ-features that have undergone agreement in narrow syntax. Suppression corresponds to non-application of Agree-Copy.

The appearance of the subjunctive status marker for perfective remains as a stipulated property of the construction.

Stiebels (2006) posits a constraint called Def/+hr that directly forces object agreement to be manifested.

Stiebels (2006) reports sporadic instances of agreement with an oblique object in the AF construction, but these unusual cases of agreement have to be put aside for the purposes of this article. This type of agreement is problematic for the general theory of agreement in the first place.

One might wonder whether it is appropriate to generate the ϕ-feature set for objects when they are obliquely marked. Given the original transitive nature of the verb, however, the transitive version of v will guarantee it, which in turn lends support to attributing object agreement to v, or whatever head is responsible for the introduction of an external argument.

It is the ϕ-feature suppression operation itself, not Vocabulary Insertion, that is responsible for the introduction of the abstract AF marker. Note that the AF marker does not care about actual ϕ-feature values. The allomophy of AF marking is probably taken care of by cyclic derivation, as in the model of Embick (2010).

This requirement cannot be limited to the absolutive series, because of split ergativity in languages like Yucatec, where the intransitive subject is cross-referenced with an ergative marker in the incompletive aspect. See Tonhauser (2007) for discussion in relation to subject extraction.

In Tsotsil, 3rd person plural is expressed by -ik, which can also be used together with a preverbal 2nd person ergative or absolutive marker to index 2nd person plural. Thus, Tsotsil is one of the Mayan languages, just mentioned above, where number marking is separated from person marking. The fact is noted by Preminger (2014) as evidence for the separability of person and number in syntactic agreement, but it is relevant for the characterization of Vocabulary items as well. See Aissen (1987) for details.

References

Aissen, J. (1987). Tzotzil clause structure. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Aissen, J. (1999a). Agent focus and inverse in Tzotzil. Language, 75, 451–485.

Aissen, J. (1999b). Markedness and subject choice in Optimality Theory. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 17, 673–711.

Aissen, J. (2011). On the syntax of agent focus in K’ichee’. In K. Shklovsky, P. Mateo Pedro, & J. Coon (Eds.), Proceedings of formal approaches to Mayan linguistics. MIT working papers in linguistics: Vol. 63. (pp. 1–16). Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Aissen, J. (2017). Correlates of ergativity in Mayan. In J. Coon, D. Massam, & L. D. Travis (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of ergativity (pp. 737–758). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ajsivinac Sian, J., & Henderson, R. (2011). Agent focus morphology without a focused agent: restrictions on objects in Kaquchikel. In K. Shklovsky, P. Mateo Pedro, & J. Coon (Eds.), Proceedings of formal approaches to Mayan linguistics (pp. 17–21). MIT working papers in linguistics: Vol. 63. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Albright, A., & Fuß, E. (2012). Syncretism. In J. Trommer (Ed.), The morphology and phonology of exponence (pp. 236–288). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anagnostopoulou, E. (2005). Strong and weak person restrictions: a feature checking analysis. In L. Heggie & F. Ordóñz (Eds.), Clitic and affix combinations (pp. 199–235). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Arregi, K., & Nevins, A. (2012). Morphotactics: Basque auxiliaries and the structure of spellout. Dordrecht: Springer.

Assmann, A., Georgi, D., Heck, F., Müller, G., & Weisser, P. (2015). Ergatives move too early: On an instance of opacity in syntax. Syntax, 18, 343–387.

Ayres, G. (1983). The antipassive “voice” in Ixil. International Journal of American Linguistics, 49, 20–45.

Béjar, S., & Rezac, M. (2003). Person licensing and the derivation of PCC effects. In A. T. Pérez-Leroux & Y. Roberge (Eds.), Romance linguistics: theory and acquisition (pp. 49–62). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bergqvist, H. (2007). Agent focus in Yukatek and Lakandon Maya. In Z. Antić, C. B. Chang, C. S. Sandy, & M. Toosarvandani (Eds.), Proceedings of the thirty-third annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 28–38). Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Berinstein, A. (1985). Evidence for multiattachment in K’ekchi Mayan. New York: Garland.

Bonet, E. (1995). Feature structure of Romance clitics. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 13, 607–647.

Bohnemeyer, J. (2009). Linking without grammatical relations in Yucatec: alignment, extraction, and control. In Y. Nishina, Y. M. Shin, S. Skopeteas, E. Verhoeven, & J. Helmbrecht (Eds.), Issues in functional-typological linguistics and language theory: a festschrift for Christian Lehmann on the occasion of his 60th birthday (pp. 185–214). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Brandi, L., & Cordin, P. (1989). Two Italian dialects and the null subject parameter. In O. Jaeggli & K. J. Safir (Eds.), The null subject parameter (pp. 111–142). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Can Pixabaj, T. A. (2017). K’iche’. In J. Aissen, N. C. England, & R. Zavala Maldonado (Eds.), The Mayan languages (pp. 461–499). London: Routledge.

Chomsky, N. (2001). Derivation by phase. In M. Kenstowicz (Ed.), Ken Hale: a life in language (pp. 1–52). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Coon, J. (2016). Mayan morphosyntax. Language and Linguistics Compass, 10, 515–550.

Coon, J., Mateo Pedro, P., & Preminger, O. (2014). The role of case in A-bar extraction asymmetries. Linguistic Variation, 14, 179–242.

Craig, C. G. (1979). The antipassive and Jacaltec. In L. Martin (Ed.), Papers in Mayan linguistics (pp. 139–164). Columbia: Lucas Brothers.

Davies, W. D., & Sam-Colop, L. E. (1990). K’iche’ and the structure of antipassive. Language, 66, 522–549.

Dayley, J. P. (1981). Voice and ergativity in Mayan languages. Journal of Mayan Linguistics, 2, 3–82.

Dayley, J. P. (1985a). Voice in Tzutujil. In J. Nichols & A. Woodbury (Eds.), Grammar inside and outside the clause (pp. 192–226). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dayley, J. P. (1985b). Tzutujil grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Embick, D. (2010). Localism versus globalism in morphology and phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Embick, D. (2015). The morpheme: a theoretical introduction. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Embick, D., & Noyer, R. (2007). Distributed morphology and the syntax-morphology interface. In G. Ramchand & C. Reiss (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces (pp. 289–324). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

England, N. C. (1983). Eragativity in Mamean (Mayan) languages. International Journal of American Linguistics, 49, 1–19.

England, N. C. (1989). Comparing Mam (Mayan) clause structures: subordinate versus main clauses. International Journal of American Linguistics, 55, 283–308.

England, N. C. (1991). Changes in basic word order in Mayan languages. International Journal of American Linguistics, 57, 446–486.

England, N. C. (2011). Plurality agreement in some Eastern Mayan languages. International Journal of American Linguistics, 77, 397–412.

Erlewine, M. Y. (2016). Anti-locality and optimality in Kaqchikel Agent Focus. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 34, 429–479.

Georgi, D. (2012). A relativized probing approach to person encoding in local scenarios. Linguistic Variation, 12, 153–210.

Gutiérrez-Bravo, R., & Monforte, J. (2011). Focus, agent focus and relative clauses in Yucatec Maya. In H. Avelino (Ed.), New perspectives in Mayan linguistics (pp. 257–274). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Halle, M. (1997). Impoverishment and fission. In B. Bruening, Y. Kang, & M. McGinnis (Eds.), PF: papers at the interface (pp. 425–450). MIT working papers in linguistics: Vol. 30. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In K. Hale & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from Building 20 (pp. 111–176). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harbour, D. (2011). Valence and atomic number. Linguistic Inquiry, 42, 561–594.

Harbour, D. (2016). Impossible persons. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harley, H., & Ritter, E. (2002). Person and number in pronouns: a feature-geometric analysis. Language, 78, 482–526.

Larsen, T. W. (1981). Functional correlates of ergativity in Aguacatec. In Proceedings of the seventh annual meeting of Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 136–153). Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Larsen, T. W. (1987). The syntactic status of ergativity in Quiché. Lingua, 71, 33–59.

Larsen, T. W., & Norman, W. M. (1979). Correlates of ergativity in Mayan grammar. In F. Plank (Ed.), Ergativity (pp. 347–370). New York: Academic Press.

Law, D. (2009). Pronominal borrowing among the Maya. Diachronica, 26, 214–252.

Law, D. (2013). Mayan historical linguistics in a new age. Language and Linguistics Compass, 7, 141–156.

Lockwood, H. T., & Macaulay, M. (2012). Prominence hierarchies. Language and Linguistics Compass, 6, 431–446.

McCarthy, J., & Prince, A. (1995). Faithfulness and reduplicative identity. In J. Beckman, L. Dickey Walsh, & S. Urbanczyk (Eds.), Papers in optimality theory (pp. 249–384). Amherst: GLSA.

Menn, L., & McWhinney, B. (1984). The repeated morph constraint: toward an explanation. Language, 60, 519–541.

Myers, S. (1997). OCP effects in Optimality Theory. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 15, 847–892.

Nevins, A. (2007). The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 25, 273–313.

Nevins, A. (2011). Multiple agree with clitics: person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 29, 939–971.

Nevins, A. (2012). Haplological dissimilation at distinct stages of exponence. In J. Trommer (Ed.), The morphology and phonology of exponence (pp. 84–116). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norcliffe, E. (2009). Head-marking in usage and grammar: A study of variation and change in Yucatec Maya. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University.

Pescarini, D. (2010). Elsewhere in Romance: evidence from clitic clusters. Linguistic Inquiry, 41, 427–444.

Plag, I. (1998). Morphological haplology in a constraint-based morpho-phonology. In W. Kehrein & R. Wiese (Eds.), Phonology and morphology of the Germanic languages (pp. 199–215). Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Preminger, O. (2014). Agreement and it failures. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Samuels, B. (2014). On the biological origins of linguistic identity. In K. Nasukawa & H. van Riemsdijk (Eds.), Identity relations in grammar (pp. 341–364). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Silverstein, M. (1976). Hierarchy of features and ergativity. In R. M. W. Dixon (Ed.), Grammatical categories in Australian languages (pp. 112–171). Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Smith-Stark, T. (1978). The Mayan antipassive. In N. C. England (Ed.), Papers in Mayan linguistics (pp. 169–187). Columbia: University of Missouri.

Stemberger, J. P. (1981). Morphological haplology. Language, 57, 791–817.

Stiebels, B. (2006). Agent focus in Mayan languages. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 24, 501–570.

Tada, H. (1993). A/A-bar partition in derivation. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Tonhauser, J. (2007). Agent focus and voice in Yucatec Maya. In J. Cihlar, A. Franklin, D. Kaise, & I. Kimbara (Eds.), Proceedings of the 39th meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society (pp. 540–558). Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Trechsel, F. R. (1993). Quiché focus constructions. Lingua, 91, 33–78.

van Koppen, M. (2005). One probe – two goals: Aspects of agreement in Dutch dialects. Ph.D. dissertation, Leiden University, Leiden.

Verhoeven, E., & Skopeteas, S. (2015). Licensing focus constructions in Yucatec Maya. International Journal of American Linguistics, 81, 1–40.

Watanabe, A. (2013). Person-number interaction: impoverishment and natural classes. Linguistic Inquiry, 44, 469–492.

Watanabe, A. (2015). Valuation as deletion: inverse in Kiowa-Tanoan. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 33, 1387–1420.

Yip, M. (1998). Identity avoidance in phonology and morphology. In S. G. Lapointe, D. K. Brentari, & P. M. Farrell (Eds.), Morphology and its relation to phonology and syntax (pp. 216–246). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Zavala, R. (1997). Functional analysis of Akatek voice constructions. International Journal of American Linguistics, 63, 439–474.

Zúñiga, F. (2006). Deixis and alignment: inverse systems in indigenous languages of the Americas. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank reviewers as well as the editor Ingo Plag for helping me hammer out the final version. One of the reviewers indeed encouraged me by pointing out that an approach that assigns a single morphological realization slot was attempted before. I am also grateful to Ken Hiraiwa for comments on an earlier version and to Jürgen Bohnemeyer and Judith Tonhauser for responding to my queries. The research reported here is partially supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 22520492 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, A. The division of labor between syntax and morphology in the Kichean agent-focus construction. Morphology 27, 685–720 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-017-9312-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-017-9312-0