Abstract

The objective was to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care, cannabis use, and behaviors that increase the risk of STIs among men living with or at high risk for HIV. Data were from mSTUDY — a cohort of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. Participants who were 18 to 45 years and a half were HIV-positive. mSTUDY started in 2014, and at baseline and semiannual visits, information was collected on substance use, mental health, and sexual behaviors. We analyzed data from 737 study visits from March 2020 through August 2021. Compared to visits prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were significant increases in depressive symptomatology (CES-D ≥ 16) and anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10). These increases were highest immediately following the start of the pandemic and reverted to pre-pandemic levels within 17 months. Interruptions in mental health care were associated with higher substance use (especially cannabis) for managing anxiety/depression related to the pandemic (50% vs. 31%; p-value < .01). Cannabis use for managing pandemic-related anxiety/depression was higher among those reporting changes in sexual activity (53% vs. 36%; p-value = 0.01) and was independently associated with having more than one sex partner in the prior 2 weeks (adjusted OR = 1.5; 95% CI 1.0–2.4). Our findings indicate increases in substance use, in particular cannabis, linked directly to experiences resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated interruptions in mental health care. Strategies that deliver services without direct client contact are essential for populations at high risk for negative sexual and mental health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People living with HIV and those at increased risk for HIV are at high risk for other health problems, including substance use, mental health issues, and socioeconomic vulnerabilities [1,2,3] The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting efforts to curb the spread of infection—such as stay-at-home orders and physical distancing mandates—and the resulting social isolation are likely to exacerbate these issues [4]. A survey of young adults in the USA found that immediately following the declaration of a state of emergency due to COVID-19, levels of depression and anxiety increased with high levels of loneliness and COVID-19-specific worry being associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. [5] Factors found to be associated with pandemic-related depression and anxiety include being younger, being a racial/ethnic minority, or being diagnosed with a chronic disease. [6,7,8]

The pandemic-related increases in mental health issues may also extend to substance misuse. Prior studies of disasters, including the aftermath of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic, found increased rates of substance use. [9,10,11,12,13] Emerging data related to the COVID-19 pandemic seem to corroborate these findings, with one study noting a “surge of addictive behaviors” including food, shopping, and increased reported use of cannabis, methamphetamine, and opioids. [14,15,16] Studies that specifically focused on men who have sex with men (MSM)—including both those who were HIV-positive and at increased risk for HIV—found that changes in substance use and mental health were also associated with behaviors that not only increased the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection—the virus causing COVID-19—but also had implications in terms of STI/HIV transmission. [17,18,19] For instance, one study found that those who had sex with casual partners during pandemic restrictions were more likely to report using substances including alcohol as compared to those who avoided interactions with casual sex partners. [17]

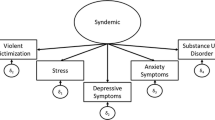

Engagement in ongoing health care and prevention is especially critical to the health of vulnerable populations living at the intersection of multiple colliding epidemics of COVID-19, substance use, mental health, and HIV. In order to reduce the potential for SARS-CoV-2 transmission, many clinics stopped in-person clinical encounters and switched to telehealth visits starting in March 2020. While telehealth outcomes in general — including among those who live with HIV — have been largely positive, telehealth has the potential to miss the most high needs and socioeconomically vulnerable patients. [20,21,22,23] Beyond limited access to technology requirements for telehealth visits including a cell phone or computer and Internet connectivity (i.e., unlimited data or cell services), [24] privacy concerns and the absence of confidential surroundings may also be an issue. In fact, one study found that even with an intervention to improve telehealth attendance, access to virtual medical care was still challenging among people living with HIV (PLWH) who were experiencing homelessness. [25] Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on substance use, changes in mental health, and interruptions in mental health care among HIV-positive and high-risk HIV-negative men. Specifically, we focus on cannabis use given the high prevalence of use, ease of access, and its use as the substance of choice to manage negative affect including anxiety and depression. [26,27,28] We describe the prevalence and correlates of interruptions in mental healthcare as well as factors associated with cannabis use for COVID-19 related anxiety and depression. We compare those who report interruptions in mental health care to those who did not experience these interruptions and hypothesize that those experiencing interruptions in mental health care will experience increases in depression and anxiety and will also report other negative health behaviors, including increased substance use and increases in sexual risk behaviors.

Methods

Study Population and Design

Data for this study were based on those collected from participants in the mSTUDY — a National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) funded cohort of racial/ethnically diverse, HIV-positive, and high-risk HIV-negative MSM. Details of the mSTUDY have been previously described, [29, 30] but briefly, participants were recruited from two study sites in Los Angeles, CA, including a community-based organization providing services for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community and a community-based university research clinic. Study enrollment started in August 2014, and cohort participation is ongoing. Eligible participants (1) were between 18 and 45 years of age at the time of enrollment, (2) identified as male at birth, (3) if HIV-negative, reported condomless anal intercourse with a male partner in the past 6 months, (4) were capable of providing informed consent, and (5) were willing and able to return to the study site every 6 months to complete study-related activities. By design, half of the participants were living with HIV, and half were substance using. Following the COVID-19 pandemic “stay-at-home order” in California, all in-person research activities were stopped on March 13, 2020, and remote study visits were launched starting March 31, 2020. For this analysis, we included all participant remote study visit data collected from March 31, 2020, through August 30, 2021 (n = 324 participants; 737 study visits).

Study Procedures and Data Collection

The Institutional Review Board at the University of California Los Angeles approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation. During in-person study visits, which occur every 6 months, participants complete a self-administered, computer-assisted survey and provide biological specimen for HIV testing (HIV antibodies for those who are HIV-negative and HIV viral load testing for those who are HIV positive). During the remote visits included as part of this analysis, no biological samples were collected. HIV status was based on testing done at the previous follow-up visit, which occurred 6 to 8 months prior for most respondents. Participants were sent an electronic link to the study questionnaire for each remote study visit, which was comparable to the survey used as part of the in-person study visits and included additional questions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to sociodemographic characteristics, the questionnaire collected information on current substance use, mental health, sexual risk behaviors, and COVID-19 experiences and the impact of the pandemic on overall health and well-being.

Substance Use Measures

Participants were asked to report on substance use in the past 6 months, with substance users also reporting on specific substances used in the previous 2 weeks, including the following: (1) cannabis, (2) cocaine, (3) ecstasy, (4) heroin, (5) methamphetamine, (6) “poppers,” and (7) illicit use of prescription medications. Those who reported substance use were also asked, “to what extent are you using [reported substance] to manage any anxiety about changes in your life caused by COVID-19?” with a parallel question asked for depression. Additionally, those who reported using a given substance were also asked to report on any changes in their amount of substance use, with response choices including “I use a lot more,” “I use more,” “I use the same,” “I use less,” and “I use a lot less.”

Mental Health Measures

Current symptoms of depression were measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D20), and anxiety was measured using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7). Interruptions in mental health care was based on a question that asked “How much has the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the care you receive from others (e.g., counselor, therapist, support groups) for mental health?” with response choices including “quite a bit,” “extremely,” “somewhat,” “a little bit,” “not at all,” and “do not receive mental health care.”

COVID-19 Related Measures

Other questions relevant to this analysis included an assessment of experiences during COVID-19 with a prompt stating “which of the following are you experiencing during COVID-19?” with answer choices allowing participants to select all that apply from the following: (1) more anxiety; (2) more depression; (3) more sleep, less sleep, or other changes in your normal sleep pattern; (4) a change in sexual activity; (5) personal financial loss (e.g., lost wages, job loss, investment/retirement loss); and (6) getting financial support from family, friends, partners, an organization, or someone else. Finally, participants were also asked to report on a scale of 1 to 10, how worried they were about the COVID-19, how socially isolated they felt, and how they would rate their quality of life.

Analytic Strategy

This analysis focused on two outcomes, including cannabis use for the management of anxiety/depression during COVID-19 and interruptions in mental health care. Univariate analyses provided descriptive statistics for the sample overall and by cannabis use and mental healthcare status. Changes in anxiety and depressive symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic were examined over time with comparisons made to pre-pandemic levels. Specifically, we compared CES-D20 and GAD-7 scores for the last visit that occurred within the 12-month timeframe before the COVID-19 pandemic shelter-in-place orders (March 2019–March 2020) to three pandemic timeframes including March 31–August 30, 2020, September 1, 2020–February 28, 2021, and March 1–August 30, 2021 using the McNemar test. Comparisons of demographics, other substance use, and impact and experiences during COVID-19 by cannabis use status were based on t-tests, chi-square methods, and other nonparametric tests as appropriate while adjusting for the effect of the subject (i.e., repeated measures). Factors associated with the outcomes of interest were assessed using regression analysis with generalized estimating equations (GEE) in order to account for the within-subject correlations. [31, 32] Univariate analyses along with a priori knowledge informed variables for inclusion in the multivariable models. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of Study Population

At the time of the remote study visit, the average participant age was 35.6 years (SD 6.8), with 42% identifying as Black/African American, followed by 42% Hispanic/Latinx, and 11% Caucasian/White (Table 1). One-third reported being unemployed and 19% reported experiencing unstable housing. The prevalence of substance use was high, with 59% reporting substance use in the past 2 weeks. The most prevalent substance used was cannabis with 40% reporting its use, followed by 25% reporting methamphetamine, 7% reporting cocaine, and 11% reporting illicit use of prescription drugs. Comparing participants living with HIV to those who were HIV negative, we note that PLWH were slightly older and had a slightly different substance use profile. PLWH reported slightly more methamphetamine use when compared to those who were HIV negative (31% vs. 18%, respectively; p-value = < 0.01) but significantly less cannabis use (35% vs. 46%, respectively; p-value = 0.04). Beyond differing substance use patterns, PLWH expressed slightly higher levels of worry about COVID-19, with no other differences noted when comparing PLWH to those who were HIV negative with respect to experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic (Supplement Table 1).

The median CES-D score was 15 (IQR: 9–25), and 27% reported moderate to severe anxiety (GAD-7 scores ≥ 10). When compared to visits occurring prior to the pandemic (and within a year of the remote visit), we found that there were increases in the prevalence of depressive symptomatology (CES-D scores ≥ 16) and moderate to severe anxiety (Figs. 1 and 2). For instance, in the year prior to the pandemic, 19% of participants had GAD-7 scores consistent with moderate to severe anxiety, which increased to 26% during the first 5 months of the pandemic (p-value < 0.01; based on paired data), declined slightly to 24% in the subsequent 5 months (p-value < 0.01), and reached pre-pandemic levels (20%) within the final follow-up period which occurred 11- to 17-months post shelter-in-place orders (Fig. 1). Likewise, depressive symptoms peaked within the first follow-up timeframe at 49% vs. 42% pre-pandemic (p-value < 0.01; based on paired data) and reached pre-pandemic levels after 11 to 17 months of follow-up (Fig. 2). A similar pattern was noted when the analysis was restricted to those who reported using cannabis to manage their COVID-19 related anxiety. However, the levels of depressive symptomatology and anxiety were even more pronounced among this group.

Prevalence and Factors Associated with Interruptions in Mental Health Care

Among participants who reported receiving care from others (e.g., counselor, therapist, support groups) for their mental health, 73% (216/296) reported interruptions in care resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. No differences were noted in sociodemographic characteristics and HIV status for those with and without interruptions in mental health care (Table 2). Based on a 10-point scale, average level of worry regarding COVID-19, as well as current feelings of social isolation, anxiety, and depression, was higher among those with interruptions in their mental health care. For instance, 62% of those with interruptions in mental health care reported more anxiety during the pandemic as compared to 44% among those without interruptions in their mental health care (p-value < 0.01). Mental healthcare disruptions were also associated with increased alcohol and substance use (31% vs. 20% among those with no interruptions in mental health care; p-value = 0.01). Furthermore, a significantly higher proportion of those who reported interruptions in their mental health care also reported substance use as a way to manage anxiety and/or depression related to changes in their life caused by COVID-19.

Prevalence of Cannabis Use for Anxiety/Depression Related to COVID-19 Pandemic

Using cannabis to manage anxiety or depression related to life changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic was reported by 31% of participants (Table 3). Those who reported using cannabis were younger compared to those who did not report using cannabis to manage COVID-19 related anxiety/depression (mean age 34.8 vs. 36.6, respectively; p-value = 0.03). However, no other differences were noted in sociodemographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity, employment status, or HIV status. Additionally, cannabis use for the management of COVID-19 related anxiety/depression was higher among those who reported COVID-19 related financial loss (48% vs. 38%; p-value = 0.05), use of other substances beyond cannabis (52% vs. 33%; p-value < 0.01), increases in other substance and alcohol use (47% vs. 19%; p-value < 0.01), and changes in sexual activity including more than one sex partner in the past 2 weeks (54% vs. 36%; p-value < 0.01).

Based on multivariable analyses, adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and HIV status, interruptions in mental health care were independently associated with cannabis use for managing COVID-19 related anxiety/depression. Specifically, we found that those who reported interruptions in their mental health care had 1.9 times increased odds of reporting cannabis use for managing COVID-19 related anxiety as compared to those who did not have interruptions in their mental health care (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.9; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.2–2.9)(data not shown). Additionally, those who reported using cannabis for anxiety/depression had a 1.5 increased odds of having more than one anal sex partner in the prior 2 weeks (AOR = 1.5; 95% CI 1.0–2.4), even after adjusting for other factors including age, race/ethnicity, and HIV status.

Discussion

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been vast in terms of who has been impacted and broad in terms of how people have been affected. Our findings highlight the experiences of those living at the intersection of multiple colliding epidemics and vulnerabilities, including COVID-19, substance use, mental health, and HIV. In particular, our results indicate increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety with the highest levels noted in the most immediate timeframe following the COVID-19 pandemic and a reversion to pre-pandemic levels within 17 months of follow-up. Our results also indicate changes in substance use linked directly to experiences resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, with a high proportion of participants reporting cannabis use to cope with their heightened anxiety and depression. Furthermore, we find that interruptions in care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly interruptions in mental health care, can link with negative outcomes along substance use and STI/HIV risk and underscore the intersectional vulnerabilities experienced by these individuals.

Our finding that interruptions in mental health care directly linked to substance use, which in turn was linked to other negative outcomes, suggests that strategies to ensure continuity of care among this population are critical. The interruptions in care during the COVID-19 pandemic may be partly explained by loss of employment and subsequent loss of health insurance. However, given that rates of unemployment were not different among those with and without interruptions in mental health care, it is likely that these interruptions instead resulted from pandemic-related healthcare provider cancelations of in-person services and the consequent switch to telehealth visits. Beyond limited access, to the technology required for telehealth visits including cell phone or computers and Internet connectivity (i.e., unlimited data or cell services), [24] privacy concerns and limited access to confidential surroundings may also be an issue among this study population. Among participants who reported interruptions in mental health care, 20% also noted unstable housing, and less than half engaged in telehealth visits. This is supported by data from a community-based organization providing substance use treatment for HIV-affected individuals which found that all clients were unable to attend telehealth visits. [33] Addressing the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare delivery and, in particular, mental health care for those most vulnerable may require novel strategies that move beyond standard telehealth services. Strategies such as “task sharing” or “task shifting”—where care extenders and other nonclinical staff deliver both medical and behavioral health care—have been successfully implemented in low-resource settings and may serve as a potential option in lieu of telehealth or in-person visits. [34,35,36] The “task-sharing” model was adapted by a substance use treatment center in the USA, which used peer coaches to deliver the psychotherapy component of their substance use recovery program. [33] Using peer coaches, who coordinated with a program therapist, offered flexibility both in terms of time (allowed for evening and weekend visits) and technology requirements (e.g., texting or outdoor in-person meetings). This model was acceptable and showed preliminary efficacy in delivering behavioral healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. [33]

Among our study participants, cannabis use for the purpose of managing COVID-19 related increases in anxiety and symptoms of depression was independently associated with sexual behaviors that increase the risk of STIs, namely, number of anal sex partners. Findings related to cannabis use and sexual risk behaviors have been mixed, with prior work from mSTUDY indicating that cannabis use was in fact associated with lower STI risk behaviors and STIs. [37,38,39] However, unique to this analysis is our focus on cannabis use specifically to manage mental health distress resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Social isolation caused by stay-at-home orders likely triggers both substance use, sexual compulsivity, and behaviors that increase the risk of STIs. [40, 41] The increase in reported sex partners raises additional concern when coupled with findings from other studies that indicate COVID-19 has reduced access to STI/HIV testing and other prevention tools such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). [17, 18] Data among our participants seem to support this as only 30% of those who were HIV negative reported current PrEP use (data not shown). Beyond the STI transmission risks, these findings also have implications in terms of SARS-CoV-2 transmission risk. For instance, a recent study of MSM in Israel found that those who reported having sex with a casual sex partner during a period when strict social-distancing mandates were in place were also more likely than those who did not have casual sex partners to report being agreeable to having sex with a person diagnosed with COVID-19. [17] The same task-shifting strategies used to extend mental health and substance use care can be extended to provide wrap-around services including provision of self-testing kits for STIs/HIV and linkage to other HIV prevention services.

These findings should be interpreted with consideration to a number of study limitations. First, our data—especially data on sexual risk behaviors and substance use—were based on self-report, which can result in an underestimation of these behaviors. However, the use of computer-assisted self-interviews may help minimize potential response bias and reluctance in reporting behaviors that are socially stigmatized or illegal. Disentangling the temporal ordering of substance use, depressive symptoms, and anxiety is challenging; given our data, it is difficult to say whether substance use led to mental health issues and sexual risk behaviors or whether the symptoms led to substance use and subsequent sexual risk behaviors. Furthermore, the potential chronicity and persistence of the behaviors, the disruptions in mental health care, and the association with our outcome of interest make it difficult to determine which is the cause and which is the effect. However, by focusing specifically on cannabis use related to increased pandemic-related mental distress, we hope to limit some of the challenges related to the temporal ordering of events. Finally, this study was based on participants recruited from a community-based sexual health clinic and a university-based research clinic in Los Angeles and may not be generalizable to other populations.

In conclusion, interruptions in mental health care among this exceptionally vulnerable population can result in a cascade of effects that increases infectious disease risk, including STIs as well as COVID-19. While some of the negative mental health effects regress to baseline levels within a year of the major disruptions caused by the pandemic, there exists an extended vulnerable period where many of the same socioeconomic and structural vulnerabilities that place populations at risk for STIs also increase vulnerability to infections with SARS-CoV-2, as well as other negative outcomes. [42, 43] Novel strategies beyond telehealth that deliver services without direct client contact are needed to bridge the care gap for marginalized and low-resourced populations and address the social determinants of health that lead to health care and mental and sexual health disparities.

References

Xiao L, Qi H, Wang YY, et al. The prevalence of depression in men who have sex with men (MSM) living with HIV: a meta-analysis of comparative and epidemiological studies. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:112–9.

Turpin RE, Salerno JP, Rosario AD, Boekeloo B. Victimization, substance use, depression, and sexual risk in adolescent males who have sex with males: a syndemic latent profile analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;50(3):961–71.

Westmoreland DA, Carrico AW, Goodwin RD, Pantalone DW, Nash D, Grov C. Higher and higher? Drug and alcohol use and misuse among HIV-vulnerable men, trans men, and trans women who have sex with men in the United States. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56(1):111–22.

Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):817–8.

Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, Hahm HC. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113172.

Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3740.

Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4065.

Czeisler M, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–57.

DiMaggio C, Galea S, Li G. Substance use and misuse in the aftermath of terrorism. A Bayesian meta-analysis Addiction. 2009;104(6):894–904.

Wu P, Liu X, Fang Y, et al. Alcohol abuse/dependence symptoms among hospital employees exposed to a SARS outbreak. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43(6):706–12.

Sim K, Chong PN, Chan YH, Soon WS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related psychiatric and posttraumatic morbidities and coping responses in medical staff within a primary health care setting in Singapore. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1120–7.

Gargano LM, Welch AE, Stellman SD. Substance use in adolescents 10 years after the World Trade Center attacks in New York City. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2017;26(1):66–74.

Vlahov D, Galea S, Resnick H, et al. Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan, New York, residents after the September 11th terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(11):988–96.

Dubey MJ, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Biswas P, Chatterjee S, Dubey S. COVID-19 and addiction. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):817–23.

Rolland B, Haesebaert F, Zante E, Benyamina A, Haesebaert J, Franck N. Global changes and factors of increase in caloric/salty food intake, screen use, and substance use during the early COVID-19 containment phase in the general population in France: survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(3):e19630.

Sun Y, Li Y, Bao Y, et al. Brief report: increased addictive Internet and substance use behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Am J Addict. 2020;29(4):268–70.

Shilo G, Mor Z. COVID-19 and the changes in the sexual behavior of men who have sex with men: results of an online survey. J Sex Med. 2020;17(10):1827–34.

Santos GM, Ackerman B, Rao A, et al. Economic, mental health, HIV prevention and HIV treatment impacts of COVID-19 and the COVID-19 response on a global sample of cisgender gay men and other men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2020;25(2):311–21.

Hammoud MA, Maher L, Holt M, et al. Physical distancing due to COVID-19 disrupts sexual behaviors among gay and bisexual men in Australia: implications for trends in HIV and other sexually transmissible infections. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(3):309–15.

Dandachi D, Freytag J, Giordano TP, Dang BN. It is time to include telehealth in our measure of patient retention in HIV care. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(9):2463–5.

Ramaswamy A, Yu M, Drangsholt S, et al. Patient satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e20786.

Garcia-Huidobro D, Rivera S, Valderrama Chang S, Bravo P, Capurro D. System-wide accelerated implementation of telemedicine in response to COVID-19: mixed methods evaluation. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e22146.

León A, Cáceres C, Fernández E, et al. A new multidisciplinary home care telemedicine system to monitor stable chronic human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: a randomized study. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e14515.

Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, et al. Patient characteristics associated with choosing a telemedicine visit vs office visit with the same primary care clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e205873.

Hickey MD, Sergi F, Zhang K, et al. Pragmatic randomized trial of a pre-visit intervention to improve the quality of telemedicine visits for vulnerable patients living with HIV. J Telemed Telecare. 2020;20:1357633x20976036.

Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Ecker AH, Jeffries ER. Cannabis craving in response to laboratory-induced social stress among racially diverse cannabis users: the impact of social anxiety disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(4):363–9.

Buckner JD, Crosby RD, Silgado J, Wonderlich SA, Schmidt NB. Immediate antecedents of marijuana use: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2012;43(1):647–55.

Hathaway AD. Cannabis effects and dependency concerns in long-term frequent users: a missing piece of the public health puzzle. Addiction Research & Theory. 2003;11(6):441–58.

Javanbakht M, Ragsdale A, Shoptaw S, Gorbach PM. Transactional sex among men who have sex with men: differences by substance use and HIV status. J Urban Health. 2018;96(3):429–41.

Javanbakht M, Shoptaw S, Ragsdale A, Brookmeyer R, Bolan R, Gorbach PM. Depressive symptoms and substance use: changes overtime among a cohort of HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2020;207:107770.

Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data-analysis using generalized linear-models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22.

Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data - a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049–60.

Rogers BG, Arnold T, Schierberl Scherr A, et al. Adapting substance use treatment for HIV affected communities during COVID-19: comparisons between a sexually transmitted infections (STI) clinic and a local community based organization. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(11):2999–3002.

Joska JA, Andersen LS, Smith-Alvarez R, et al. Nurse-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression among people living with HIV (the Ziphamandla study): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(2):e14200.

Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, Unützer J. Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: a systematic review. J Rural Health. 2018;34(1):48–62.

van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, et al. Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;19(11):Cd009149.

Gorbach PM, Javanbakht M, Shover CL, Bolan RK, Ragsdale A, Shoptaw S. Associations between cannabis use, sexual behavior, and sexually transmitted infections/human immunodeficiency virus in a cohort of young men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46(2):105–11.

D’Anna LH, Chang K, Wood J, Washington TA, Ppower Team. Marijuana use and sexual risk behavior among young Black men who have sex with men in California. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;8(6):1522–32.

Morgan E, Skaathun B, Michaels S, et al. Marijuana use as a sex-drug is associated with HIV risk among Black MSM and their network. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(3):600–7.

Torres HL, Gore-Felton C. Compulsivity, substance use, and loneliness: the loneliness and sexual risk model (LSRM). Sex Addict Compuls. 2007;14(1):63–75.

Jacobs RJ, Kane MN. Correlates of loneliness in midlife and older gay and bisexual men. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2012;24(1):40–61.

Macias Gil R, Marcelin JR, Zuniga-Blanco B, Marquez C, Mathew T, Piggott DA. COVID-19 pandemic: disparate health impact on the Hispanic/Latinx population in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(10):1592–5.

Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466–7.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant number U01DA036267.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Javanbakht, M., Rosen, A., Ragsdale, A. et al. Interruptions in Mental Health Care, Cannabis Use, Depression, and Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from a Cohort of HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative MSM in Los Angeles, California. J Urban Health 99, 305–315 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-022-00607-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-022-00607-9