Abstract

Postpartum months provide a challenging period for poor women. This study examined patterns of menstrual resumption, sexual behaviors and contraceptive use among urban poor postpartum women. Women were eligible for this study if they had a birth after the period September 2006 and were residents of two Nairobi slums of Korogocho and Viwandani. The two communities are under continuous demographic surveillance. A monthly calendar type questionnaire was administered retrospectively to cover the period since birth to the interview date and data on sexual behavior, menstrual resumption, breastfeeding patterns, and contraception were collected. The results show that sexual resumption occurs earlier than menses and postpartum contraceptive use. Out of all postpartum months where women were exposed to the risk of another pregnancy, about 28% were months where no contraceptive method was used. Menstrual resumption acts as a trigger for initiating contraceptive use with a peak of contraceptive initiation occurring shortly after the first month when menses are reported. There was no variation in contraceptive method choice between women who initiate use before and after menstrual resumption. Overall, poor postpartum women in marginalized areas such as slums experience an appreciable risk of unintended pregnancy. Postnatal visits and other subsequent health system contacts provide opportunities for reaching postpartum women with a need for family planning services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Maternal health remains a major global concern since pregnancy and childbirth are the leading causes of death, disease, and disability among women 15–45 years of age.1 This concern is also well acknowledged in the fifth millennium development goal (MDG) that aims to reduce maternal deaths and provide universal access to sexual and reproductive health services by 2015.2 , 3 Evidence shows that encouraging early antenatal care visits, institutional deliveries, postnatal care, and contraceptive adoption to promote longer birth intervals are key elements in improving safe motherhood.4 – 6 Providing access to contraception is also vital in reducing unmet need which is highest in the developing world with an estimated 105–122 million married women having an unmet need annually.7 Unmet need for family planning has also been shown to be high within a 1-year period following delivery.8 – 10 In addition, levels of unmet need remain high among women who are poor, less educated, and residents of rural areas.11 , 12

In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of postpartum women who are exposed to the risk of pregnancy by having sex while using no contraceptive method within 2 years after childbirth is nearly one third.13 – 15 For these women, addressing unmet need for family planning in the postpartum period is crucial for child survival as well as maternal health. Apart from the substantial health benefits both to the mother and child, research has demonstrated an inverse relationship between birth spacing and child mortality risk,16 while higher risks for maternal mortality have been observed for women with shorter birth intervals.4 , 6 , 17 – 19

Traditionally, lactational amenorrhea (LAM), combined with prolonged postpartum sexual abstinence in some regions, was the main spacing mechanism.20 – 23 Lactational amenorrhea protection, however, is waning because of a decline in the intensity of suckling and increases in supplemental feeding with significant regional differences.24 , 25 In the absence of reasonably intensive breastfeeding, women are likely to ovulate before the end of the second postpartum month, and hence methods such as LAM contraceptive protection vary a lot in their effectiveness and are unreliable especially in the extended postpartum period.26 In some West African countries, long durations of postpartum sexual abstinence are still being reported with durations of about 12.5 months in Burkina Faso and 8.8 months in Ghana in 2003.27 , 28 In contrast, shorter periods are reported in most of Eastern and Southern Africa; for example, durations of 2.5 and 2.9 were recorded in Uganda and Kenya in 2006 and 2003, respectively.29 , 30 The reduced role of traditional birth-spacing mechanisms can be linked to the introduction of modern contraceptives, cultural transformations, and increasing urbanization in the developing world.23 , 25 For instance, in Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, and Cameroon, Benefo showed that modernization and social change negatively affected the duration of postpartum sexual abstinence.31

Modernization and social change are driven, in part, by the pace of urbanization, with the urban population of developing countries projected to grow at an average annual rate of 2.4%.32 In many African countries, increasing rates of urbanization amidst declining economies have been documented.32 Urbanization that is associated with high levels of poverty has also been linked to food insecurity with the underlying fear that, in many developing countries, a shift in the locus of poverty, food insecurity, and malnutrition from rural to urban areas is likely.33 , 34 Kenya presents a typical example as reflected in the many informal urban settlements that house over 50% of the Nairobi city population.32 , 35 These informal settlements are often characterized by congestion, crime, poor hygiene, and poverty and present many public health challenges. For instance, girls in the Nairobi slum communities initiate sexual activities earlier than their counterparts living in other urban areas in the city as well as those in the rural communities and this has implications for the ongoing HIV/AIDS prevention strategy of abstinence, being faithful, and condom use.35 – 37 Other findings on maternal health behavior show that majority of the women in informal settlements give birth without the assistance of a trained health worker.35 , 38 The maternal mortality ratio in slums at 709 per 100,000 live births has also been shown to be higher than the national average of Kenya.39 While urban areas may have numerous health facilities, there are disparities in access and provision of reproductive health services with the wealthier parts of the cities having more access to these facilities than their counterparts from the lower socioeconomic groups.15 , 40

Therefore, understanding the reproductive health needs of postpartum women in general and those living in poor urban settlements in particular has the potential to contribute to achieving the MDGs on maternal and child health. The study examines the extent and nature of postpartum protection against pregnancy afforded by amenorrhea and sexual abstinence using monthly calendar-type data collected from two urban slum settlements in Nairobi. Contraceptive use modalities are also investigated, particularly the timing of contraception in relation to resumption of menses.

Data and Methods

Study Area

The study was conducted in two Nairobi slum settlements namely: Korogocho and Viwandani. The Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS) has prospectively monitored about 60,000 individuals living in the two slums since 2002, with routine updates conducted every 4 months. The two informal settlements share common slum characteristics such as poor sanitation, high school dropout, congestion, crime, unemployment, high disease burden, and limited access to proper health facilities. The slums are served by some government health centers, together with several private for-profit outlets, faith-based organizations, nongovernmental organizations, not-for-profit health care providers, and retail outlets selling over-the-counter medicines including contraceptives.

The current study uses data from the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) component of a 5-year Urbanization, Poverty, and Health Dynamics longitudinal study. This is an ongoing open cohort, where women are recruited into the study if they had a birth from September 2006 onwards and they were living in the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance area. The MCH study is nested into the NUHDSS and relies on previously collected rich sociodemographic data from all women resident in the study area. The first baseline round of the MCH component was conducted between February and April 2007 and since then additional waves of data collection have been conducted. A total of 2,994 women had been recruited into the study by the end of August 2008 (Table 1). Interviews were conducted in Swahili, the commonly spoken national language in the settlements. During every visit, trained fieldworkers recruit new mothers who form a new cohort and updates are conducted for those mothers previously recruited.

Details of reproductive events such as breastfeeding, postpartum abstinence, postpartum amenorrhea, sex, contraceptive use, and condom use are documented in a month-to-month calendar format since the birth of the index child. For the current analysis, data from four cohorts of women collected between February 2007 to August 2008 are utilized (Table 1). The fieldwork duration for the third wave was relatively long because data collection was disrupted by the presidential election campaigns that covered most of December 2007 and later resulted into post-election violence in the first few months of 2008. To assess the effect of loss to follow-up, we compared characteristics for women who were recruited initially and women who were successfully followed up during the subsequent updates/surveys (results not shown). The distributions of selected indicators such as parity, marital status, age of woman, location, etc. were generally comparable between women present at recruitment and those who were successfully re-interviewed during the first update which allowed on average a maximum of 12 months.

Analysis Methods

The entire analysis is restricted to the first 12 postpartum months. Much of the analysis is performed in woman-months. A woman followed up for 1 year or more contributes 12 woman-months. Nearly all women in the early recruitment cohorts contributed a full 12 months of data. Women in cohort 4 contribute an average of 9 months of data. This censoring for a small minority of the sample is addressed by life-table methods and by data presentation in terms of ordinal months since birth. This approach allowed us to measure exposure to pregnancy and contraceptive use on a month-to-month basis and allowed us to assess the contribution of several event-states such as abstinence, amenorrhea, and contraception in the first 12 months of postpartum. Five women with missing information in one of the months of (retrospective) follow-up were excluded. In order to jointly assess the timing and interactions of menstrual and sexual resumption, the time since birth of the child was classified into ordinal months of mutually exclusive categories of protection and risk periods in relation to contraceptive use. For a specific woman-month:

-

A woman was protected if she was sexually abstaining (regardless of whether she was amenorrheic or not). This group provides two categories of months of protection.

-

Months when the woman was amenorrheic but not abstaining were defined as “low protection” since it is possible for a woman to fall pregnant during the first postpartum ovulation if she is sexually active.

-

Months of exposure were defined as months when the woman was not amenorrheic and she was not abstaining. These months of exposure can be protected if a woman uses contraception.

-

A fifth group included months of pregnancy after giving birth to the index child.

Descriptive statistics was used to assess patterns of postpartum infecundity (amenorrhea), contraceptive use, and sexual resumption as well as for summarizing study cohorts by selected characteristics such as age of women at recruitment, marital status, education, ethnicity, parity, fertility desires, and source of contraception. Survival analysis techniques were used to assess the time to event (resumption of menstrual flow and resumption of sexual activities and time to first contraceptive use).

Results

By August 2008, about 2,994 women from four cohorts had been interviewed (Table 1). Information on selected demographic characteristics is summarized in Table 2. About 51% of all women in the study were resident in Korogocho, leaving about 49% who were resident in Viwandani. A majority of the women were aged between 20 and 30 years and about 8% were teenage mothers. Most women had a primary school level of education at the time of their recruitment into the study (70.9%), and most women were married or cohabiting at the time of the first wave (83.8%). The most common ethnicity was Kikuyu (26%), followed by Kamba, Luo, and Luhya (Table 2). About 34% of the mothers reported to have given birth to one child and the corresponding figures for two, three, and four or more births were 29%, 16%, and 21%, respectively. For fertility desires, women who had not began sexual relations since giving birth were asked whether they would like to have another child or would prefer not to have any more children. A majority of the women (63%) indicated a desire to have more, while 5% were undecided, leaving 32% who expressed a desire not to have any more children (Table 2). Slightly less women (41%) expressed a desire for more children in cohort 1 than in the subsequent cohorts (averaging 65%). The average time since giving birth to the index child is longer for cohort 1, and this is a likely explanation for the cohort differences in fertility desires. Among women who used any method of contraception after giving birth to the index child, health facilities and pharmacies were the major sources of contraception.

Time to Menstrual, Sexual, and Contraceptive Use Resumption

Using the monthly calendar follow-up data since birth of the index child, time to first occurrence of the event of interest was analyzed using survival analysis. Monthly time was classified into ordinal months since birth, and time to resumption of menses and sex and time to initiation of contraceptive use were estimated. Figure 1 shows the survival curves for time to first menstrual resumption, time to first sexual resumption, and time to first contraceptive use by ordinal postpartum month. The results from the survival curves show that the time at which 50% of the women had resumed their menses was 6 months postpartum.

The sexual resumption curve indicates that 50% and 75% of the women had resumed their sexual relations by 3 and 5 months after giving birth, respectively. These figures suggest that more than half of the women initiate sexual relations before they resume their menses. The time to first use of a modern contraceptive method during postpartum period indicates that about 50% of the women had used a modern contraceptive method by the seventh postpartum month (Figure 1). The percentage of sexually active months after the month of resumption of sex among married/cohabiting and single mothers was 83% and 33%, respectively. With a majority of the women being married, it is likely that there is considerable sex regularity with the observed continuity. Therefore, since a majority of all women who resume sex remain sexually active thereafter, the gap between the survival curve for first resumption of menses and first use of contraception in Figure 1 is a good representation of women who are exposed to pregnancy but not under any protection.

Profiles of Menstrual Resumption, Sexual Activity, and Contraceptive Use by Months Since Birth

The calendar data allow us to control our analysis of non-use of contraception by the actual monthly exposure to sex as well as postpartum amenorrhea. Monthly contraceptive use, therefore, was summarized for the various monthly postpartum protection and risk categories for the first 12 months observed since giving birth to the index child (Table 3).

A total of 25,947 woman-months of postpartum was observed. For 63.3% of the months where women were fully exposed (i.e., both menses and sex resumed), use of a modern contraception was reported. In addition, 9.2% of these months were protected by using a traditional method leaving 27.5% unprotected months. Among those months classified as low protection (i.e., sexually active but amenorrheic), about 53% were unprotected (no contraception was used).

Some women (range 10–22%) used a contraceptive method despite the fact that sex had not yet been resumed (Table 3). The dominant methods used during this “safe period” were injectables, pills, sterilization, and intrauterine devices (IUDs). This behavior may reflect a high degree of anticipatory precaution, as women may have little control over the precise timing of sexual initiation. Similarly, some months when the women were pregnant, contraceptive use was reported, especially modern methods like condoms. The distributions in the fourth column show that 60% of the postpartum women-months fall into the last three row categories where women are either fully or partially exposed to pregnancy or are already pregnant (32% for amenorrhea plus sex; 27% for menses plus sex; and 1% for pregnant). Of this time, about 43% was not protected by any form of family planning. A graphical illustration of the menses–sexual resumptions interactions and contraceptive use mix is presented in Figure 2. The figure presents the month-by-month shares of postpartum amenorrhea, contraceptive use, sexual activity, and pregnancy status for the first 12 postpartum months.

Postpartum women whose menses have not retuned may be unaware that they are pregnant for the first few months. Therefore, the probability of underreporting pregnancies is likely to be high in this population. By focusing on each ordinal month, where each woman contributed 1 month and the woman-months were equal to the number of women, results showed that less than 5% of women reported being pregnant by the second postpartum month, although the percentages slowly increased with increasing postpartum months to about 12% by the 12th postpartum month. In addition, by the 12th month, about 23% of the woman-months were sexually active, with menstruation resumed but protected by contraceptive use (Figure 2). During the same 12th month, the proportion of women-months that were classified as amenorrheic and sexually active but with no use of contraceptive method were about 16%, while the proportion for nonamenorrheic women-months where women were sexually active and used no contraceptive methods was about 15%.

In about 12% of women-months in Nairobi slums where women reported being amenorrheic and sexually active during the 12th month, a contraceptive method was reportedly used. Examination of the 71 women, who were pregnant during the 12-month postpartum period, showed that 61% became pregnant after menses had resumed while the remaining women were amenorrheic during the month prior to getting pregnant. About 55% and 34% of the women indicated that they would have wished to have the current pregnancy later or not at all, respectively, leaving about 11% who wanted the pregnancy then. A majority (71%) of the pregnant women reported to have used no method during the previous month while others reported to have used injectables, pills, and condoms in the month preceding the new pregnancy. About 43.2% of all women used and later discontinued a modern method in the 12-month period. Among those who were pregnant but reported having used and later stopped using contraception prior to the new pregnancy, results show that within 1, 2, and 3 or more (3+) months of ceasing contraceptive use, 22%, 47%, and 31% of women got pregnant, respectively.

Menstrual Resumption and Timing of First Contraceptive Use During Postpartum

The timing of contraceptive resumption is important for a woman who intends to avoid a pregnancy during the postpartum period. Similarly, the risk of unwanted pregnancies occurring shortly after birth even before the first menses appear in the absence of contraceptive use is well known.41 , 42 Therefore, the timing of first contraceptive use as well as the timing of first sexual intercourse in relation to the resumption of menses have key implications for reproductive health outcomes. Figure 3 shows the timing of initiation of modern contraceptive use in relation to the month of resumption of menses. In addition, the figure presents the percentage of women initiating sexual relations in relation to the month of menstrual resumption. The results show that postpartum women who used contraception in the first 12 postpartum months in the slum community initiated their contraceptive use during the months following their first menstrual cycle. Initiation of sexual activity also appears to be heaped round the time of menstrual resumption, although this peak does not match the pace of starting contraceptive use during the period immediately after menstrual resumption.

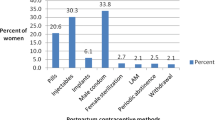

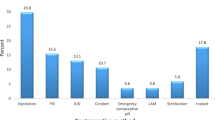

Information on contraceptive adoption for women who reported use of a contraceptive method shows that, overall, injectables (48%) and pills (22%) remain the most common methods used during the 12-month postpartum period. It should be noted that no attempt was made to distinguish progesterone-only pills from combined pills. The overall choice of contraceptive method used for the period before menses resume and for the period after was generally the same, i.e., injectables and pills were equally used during the amenorrhea and postamenorrhea periods (Figure 4).

Condom use, in contrast to other contraceptive methods during the first 12 postpartum months among women in informal settlements, was generally low. Condom use contributed only 6% to overall contraceptive protection. Other less preferred contraceptive methods included modern methods such as male and female sterilization, IUD, diaphragm, use of foams or jelly, etc.

Discussion

This study used month-by-month calendar data, similar to those collected in many Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs). However, unlike DHSs that rely on a 5-year recall period, data were collected prospectively at 4-month intervals, which should lead to much more accurate dating of key events, such as resumption of menses and initiation of contraceptive use. In addition, in contrast to DHS, the study focused on women who had recently delivered and who resided in urban informal settlements.

The use of longitudinal data allowed us to control our analysis of contraceptive use and non-use for exposure to sex and risk of pregnancy on a month-to-month basis, which is typically not possible using cross-sectional data. The results show that women in the urban slum communities resume sexual relations quite early (50% by the third month), but relatively few initiate contraceptive use during the first six postpartum months. While this may not be an issue for women who are not sexually active or who are partially protected from pregnancy by postpartum amenorrhea, particular attention needs to be paid to the group of women who have experienced a return of menses, are sexually active, and are not using any form of contraception. This group tends to peak between the third and sixth month of postpartum. The proportion of women in this group remains stable up to the 12th postpartum month, but the proportion of those becoming pregnant increases steadily, with close to 12% being pregnant by the end of the first year after giving birth. It may be important to further understand the social context of such risks and whether being a resident in an informal settlement presents particular problems of access to reproductive health services for postpartum mothers.

The observed pattern where resumption of menses among postpartum women acts as a trigger or reminder to start using contraceptives shows that women in slums understand this postpartum sign of return of full fecundity and the associated increase in the probability of having another pregnancy thereafter. This relationship between the adoption of contraception and resumption of coitus has previously been observed in studies analyzing calendar data elsewhere.43 However, by associating the return of menses with the risk of another pregnancy, women may forget that ovulation precedes the appearance of menses with even higher likelihoods of ovulation occurring as the postpartum period gets longer.43 , 44 On the other hand, the cautious group of women who initiate contraception before the return of menses acquire both natural and contraceptive protection against unwanted pregnancies. However, this advantage only counts if the selected method is a permanent one or if consistent use of the method is achieved without discontinuation. In a study of Peru and Indonesian women, results showed that women who initiated the use of pills and IUDs within the first 6 months were more likely to be pregnant after 2 years of childbirth than women who initiated similar contraception after 6 months postpartum.43 Therefore, early adoption of a contraceptive method may not necessarily translate into adequate birth spacing if continuation rates are low. This is a likely occurrence in settings such as informal settlements where education levels for women are low and constant supply or access to a given contraceptive method is not guaranteed. Following additional data collection, the analysis of the association between contraceptive initiation and continuation or discontinuation will be explored.

Among this study population, the leading choices of contraception, namely injectables and pills, are consistent with the pattern observed in the recent 2003 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey.30 However, for slum communities where the HIV prevalence is about 11.5%,45 the reported use of condoms during postpartum remains very low. Among communities where extramarital relations are common around the time of pregnancy and postpartum, low condom use may have implications for HIV/AIDS transmission.46 , 47 Condoms generally provide dual protection against pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.23 , 48 The results from the 2003 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey show that approximately 5.3% of women reported having used a condom during their recent sexual intercourse in the previous 12 months.30 This percentage was 1.9% for women who were married or cohabiting. Therefore, the observed rates in the current study compare well with Kenya national figures, since about 80% of the women in the current study were married or cohabiting. Better ways to promote condom use among married women need to be explored. For instance, in Ivory Coast, women who believed strongly in the cultural taboo that sexual relations during postpartum would harm the breastfeeding infant were more likely to accept the use of condoms with their husbands to minimize the risk of extramarital sex, as long as the semen remained in the condoms without direct contact with the breastfeeding woman.25 , 49 Alternatively, postpartum mothers may be reluctant to use condoms that have higher failure rates as well as the difficulties in maintaining the consistent use of condoms due to gender power imbalances in sexual relationships especially when compared to hormonal contraceptive methods such as pills and injectables.50 Despite this limitation, the results demonstrate the increased need for promoting the dual role of condoms as tools for HIV/STD and pregnancy prevention by HIV control and family planning programs in Africa.

In Kenya, just like any other sub-Saharan African country, contraceptive prevalence rates remain low but with considerable differences across educational and socioeconomic groups.35 In the current study, among the category of the exposed months, 63% were protected by a modern contraception. These findings were unexpected, although slums have previously shown lower fertility rates, at four births per woman in 2000, than the rest of Kenya as a whole at 4.9 births in 2003,35 and this may point to concerted efforts of many programs targeting provision of better reproductive health services to slum communities. Overall, maintaining access and availability of modern contraceptive methods especially hormonal contraceptives which are suitable for spacing remains a key challenge for meeting the need among postpartum women from less privileged societies such as those in informal settlements in Nairobi.

There are several limitations that we wish to highlight. One of the key features of carrying out longitudinal research in urban settlements is the high attrition rates due to migration. About 21% of the first cohort was lost to follow-up by the second wave. The corresponding figures for cohorts 2 and 3 were 25% and 27%, respectively. The political instability that affected Kenya during the early months of 2008 is largely responsible for the relatively high attrition for the first and second cohort. Other reasons accounting for loss to follow-up include deaths of mothers and internal changes of residence that often delays linking residents to their new locations. However, by limiting the study to the first 12 months, the effects of attrition were limited since most women were covered for this period at the time of the first or second interview.

In conclusion, the main lesson from these results is that a large proportion of women in slum communities run the risk of early postpartum conception because of delayed uptake of contraception. A distinctive feature of the period surrounding childbirth is the high motivation and intensity of contact between women and health care providers. Periods of antenatal or postpartum or routine child care visits for vaccinations need to be explored more since they present opportunities when women may be particularly receptive to messages concerning their reproductive health and that of the child. Therefore, supporting policies and programs for the integration of family planning services with postpartum contraception services present a valuable prospect to reach a large number of slum women with an unmet need during postpartum. Equally, including postpartum contraception in the training materials for traditional birth attendants is the key, since majority of the women especially in low-resource settings such as informal settlements do not deliver at designated health centers but report having delivered at home or home of a traditional birth attendant.

References

WHO. World Health Organization—The world health report 2005: Make every mother and child count. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2005.

Shankar A, Bartlett L, Fauveau V, Islam M, Terreri N. Delivery of MDG 5 by active management with data. Lancet. 2008;371(9620):1223-1224.

Konotey-Ahulu FI. MDGs, countdown to 2015, and “concern” for Africa. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):369-370.

Magadi M, Madise N, Diamond I. Factors associated with unfavourable birth outcomes in Kenya. J Biosoc Sci. 2001;33(2):199-225.

Magadi M, Diamond I, Madise N, Smith P. Pathways of the determinants of unfavourable birth outcomes in Kenya. J Biosoc Sci. 2004;36(2):153-176.

Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM. Maternal morbidity and mortality associated with interpregnancy interval: Cross sectional study. BMJ. 2000;321(7271):1255-1259.

Ross JA, Winfrey WL. Unmet need for contraception in the developing world and the former soviet union: An updated estimate. Int Fam Plann Perspect. 2002;28(3):138-143.

Ketting E. Global unmet need: Present and future. Plan Parent Chall. 1994; (1):31–34.

Casterline JB, Sinding SW. Unmet need for family planning in developing countries and implications for population policy. Popul Dev Rev. 2000;26(4):691-723.

Ross JA, Winfrey WL. Contraceptive use, intention to use and unmet need during the extended postpartum period. Int Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;27(1):20-27.

Westoff CF. New estimates of unmet need and the demand for family planning. DHS comparative reports no. 14. Calverton: Macro International; 2006.

Ashford L. Unmet need for family planning: recent trends and their implications for programs policy brief. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau and Measure Communication; 2003.

Clements S, Madise N. Who is being served least by family planning providers? A study of modern contraceptive use in Ghana, Tanzania And Zimbabwe. Afr J Reprod Health. 2004;8(2):124-136.

Ronsmans C. Birth spacing and child survival in rural Senegal. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25(5):989-997.

Magadi MA, Zulu EM, Brockerhoff M. The inequality of maternal health care in urban sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s. Popul Stud (Camb). 2003;57(3):347-366.

Rutstein SO. Effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal, infant and under-five years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: evidence from the demographic and health surveys. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89(Suppl 1):S7-24.

Rafalimanana H, Westoff CF. Potential effects on fertility and child health and survival of birth-spacing preferences in sub-Saharan Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 2000;31(2):99-110.

Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295(15):1809-1823.

Hill K, Thomas K, AbouZahr C, et al. Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: An assessment of available data. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1311-1319.

Zulu EM. Ethnic variations and observance of postpartum sexual abstinence in Malawi. Demography. 2001;38(4):467-479.

Van Balen H, Ntabomvura V. Methods of birth spacing, maternal lactation and post partum abstinence in relation to traditional African culture. J Trop Pediatr Environ Child Health. 1976;22(2):50-52.

Kirk D, Pillet B. Fertility levels, trends, and differentials in sub-Saharan Africa in the 1980s and 1990s. Stud Fam Plann. 1998;29(1):1-22.

Cleland JG, Ali MM, Capo-Chichi V. Post-partum sexual abstinence in West Africa: Implications for AIDS-control and family planning programmes. AIDS. 1999;13(1):125-131.

Ravera M, Ravera C, Reggiori A, et al. A study of breastfeeding and the return of menses in Hoima District, Uganda. East Afr Med J. 1995;72(3):147-149.

Desgrees-du-Lou A, Brou H. Resumption of sexual relations following childbirth: Norms, practices and reproductive health issues in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13(25):155-163.

Speroff L, Mishell DR Jr. The postpartum visit: It's time for a change in order to optimally initiate contraception. Contraception. 2008;78(2):90-98.

Burkina Faso Demographic and Health Survey (BFDHS). Burkina Faso Government and ORC Macro: Enquête Démographique et de Santé du Burkina Faso 2003. Ouagadougou: Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie; 2004.

Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. Ghana Government and ORC MAcro: Ghana demographic and health survey 2003. Accra Ghana Statistical Service and Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research; 2004.

Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. Uganda demographic and health survey 2006. In: UBoS, ed. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) ORC MACRO; 2006.

Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Kenya government and ORC macro: Kenya demographic and health survey 2003. Kenya DHS. Nairobi: Central Bureau of Statistics and Ministry of Health; 2003.

Benefo KD. The determinants of the duration of postpartum sexual abstinence in West Africa: A multilevel analysis. Demography. 1995;32(2):139-157.

UN-HABITAT. United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-HABITAT). The State of African Cities 2008—A framework for addressing urban challenges in Africa. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT; 2008.

UN-HABITAT. The challenges of slums: Global report on human settlements. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT; 2003.

Atkinson SJ. Urban–rural comparisons of nutrition status in the Third World. Food Nutrition Bulletin. 1993;14(4):337-340.

African Population and Health Research Center. Population and health dynamics in Nairobi’s informal settlements. Nairobi: African Population and Health Research Center; 2002.

Zulu EM, Dodoo FN, Ezeh AC. Sexual risk-taking in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, 1993–8. Popul Stud (Camb). 2002;56(3):311-323.

Dodoo FN, Zulu EM, Ezeh AC. Urban–rural differences in the socioeconomic deprivation—Sexual behavior link in Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(5):1019-1031.

Fotso JC, Ezeh A, Madise N, Ziraba A, Ogollah R. What does access to maternal care mean among the urban poor? Factors associated with use of appropriate maternal health services in the slum settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(1):130-137.

Ziraba AK, Madise N, Mills S, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh A. Maternal mortality in the informal settlements of Nairobi city: What do we know? Reprod Health. 2009;6:6.

Boerma JT, Bryce J, Kinfu Y, Axelson H, Victora CG. Mind the gap: Equity and trends in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health services in 54 countdown countries. Lancet. 2008;371(9620):1259-1267.

Hubacher D, Mavranezouli I, McGinn E. Unintended pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa: Magnitude of the problem and potential role of contraceptive implants to alleviate it. Contraception. 2008;78(1):73-78.

Sedgh G, Bankole A, Oye-Adeniran B, Adewole IF, Singh S, Hussain R. Unwanted pregnancy and associated factors among Nigerian women. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32(4):175-184.

Becker S, Ahmed S. Dynamics of contraceptive use and breastfeeding during the post-partum period in Peru and Indonesia. Population Studies. 2001;55:165-179.

Gray RH, Campbell OM, Apelo R, et al. Risk of ovulation during lactation. Lancet. 1990;335(8680):25-29.

African Population and Health Research Center. The economic, health, and social context of HIV infection in informal urban settlements of Nairobi. Nairobi: African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC); 2009.

Carpenter LM, Kamali A, Ruberantwari A, Malamba SS, Whitworth JA. Rates of HIV-1 transmission within marriage in rural Uganda in relation to the HIV sero-status of the partners. Aids. 1999;13(9):1083-1089.

Kamali A, Carpenter LM, Whitworth JA, Pool R, Ruberantwari A, Ojwiya A. Seven-year trends in HIV-1 infection rates, and changes in sexual behaviour, among adults in rural Uganda. Aids. 2000;14(4):427-434.

Cleland J, Ali MM, Shah I. Trends in protective behaviour among single vs. married young women in sub-Saharan Africa: The big picture. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(28):17-22.

Williamson NE, Liku J, McLoughlin K, Nyamongo IK, Nakayima F. A qualitative study of condom use among married couples in Kampala, Uganda. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(28):89-98.

Maharaj P, Cleland J. Risk perception and condom use among married or cohabiting couples in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2005;31(1):24-29.

Acknowledgment

This study is part of the Urbanization, Poverty, and Health Dynamics study that was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number GR 07830 M). We are grateful to the staff team at APHRC particularly Martin Kavao Mutua, Hildah Essendi, Latifat Ibisomi, and Jacques Emina for their comments, contributions, and efficient handling and processing of the data. We are also grateful to the study communities for agreeing to participate in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ndugwa, R.P., Cleland, J., Madise, N.J. et al. Menstrual Pattern, Sexual Behaviors, and Contraceptive Use among Postpartum Women in Nairobi Urban Slums. J Urban Health 88 (Suppl 2), 341–355 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-010-9452-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-010-9452-6