Abstract

Background

Satisfying close relationships are associated with higher levels of life satisfaction throughout the life course. Despite the fundamental role of attachment style in close relationships, few studies have longitudinally examined the association between attachment style in young adults with later life satisfaction.

Method

Data from 2,088 participants in a longitudinal birth cohort study were examined. At 21-years, participants completed the Attachment Style Questionnaire which comprises five domains reflective of internal working models of interpersonal relationships and attachment style: confidence (security), discomfort with closeness and relationships as secondary (avoidance), need for approval and preoccupation with relationships (anxiety). At 30-years, participants self-reported their overall life satisfaction. Linear regression was used to longitudinally examine the association between attachment domains at 21-years and life satisfaction at age 30.

Results

After adjustments, confidence was positively associated with life satisfaction (β = 0.41, 95% CI 0.25–0.56, p < 0.001), while need for approval was negatively associated with life satisfaction (β = -0.17, 95% CI -0.30 – -0.04, p < 0.001). Low income at 21, caring for a child by age 21, and leaving the parental home at 16-years or under were negatively associated with life satisfaction at 30-years.

Conclusion

Young adult attachment style is associated with later life satisfaction, particularly through confidence in self and others. Promoting positive internal working models of interpersonal relationships and fostering greater confidence in self and others in adolescence may be an effective strategy for improving life satisfaction later in life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social connection is a fundamental human need that plays a crucial role in promoting overall health and wellbeing across the lifespan (Martino et al., 2017) and serves as a protective factor against various adverse physical and mental health outcomes at different stages of life (Heinsch et al., 2022). Satisfying close relationships are consistently associated with higher levels of life satisfaction, happiness and overall quality of life (Gustavson et al., 2016; Kaufman et al., 2022). Attachment theory is an essential framework for understanding human relationships. An individual’s ability to connect with others and form healthy relationships is underpinned by their attachment style, which is commonly characterized by dimensions of security and insecurity. A growing body of literature suggests attachment style is important in life satisfaction. This paper provides a brief review of the current evidence for a relationship between attachment style and life satisfaction in adulthood. This study then addresses some of the gaps in the research using data from a longitudinal birth cohort and discusses the findings in the context of the existing literature.

Attachment Theory and Relationships

Attachment style plays a fundamental role in close relationships. Internal working models of attachment are shaped through bonding experiences with early caregivers which form a core mental representation of an individual and their relationships with others. Consistent and nurturing caregiving experiences contribute to the development of a positive or ‘secure’ internal working model, characterized by belief in one’s worthiness of love as well as trust in others’ availability during times of need (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). Conversely, inconsistent, fearful, or rejecting caregiving experiences often lead to a negative or ‘insecure’ inner working model, marked by negative perceptions of self and others. These mental representations of self and others manifest as attachment styles and influence individuals’ thoughts and behaviours within close relationships (Sherman et al., 2015). An individual’s inner working model of attachment influences how they respond to their emotions, both positive and negative; for example, an individual with a more insecure inner working model is more likely to respond to negative emotions with greater intensity (i.e., hyperactivated response to perceived abandonment or rejection) and be less open to exploring positive emotions (Mikulincer et al., 2013). As such, individuals with a more insecure inner working model of attachment are likely to experience greater difficulties with interpersonal communication and emotion regulation (Kobak & Bosmans, 2019; Lewczuk et al., 2021) thereby making them vulnerable to social isolation, loneliness and poor mental health (Manning et al., 2017; Nottage et al., 2022) and negatively impact their satisfaction with life.

In contrast, having a more secure inner working model of attachment is found to moderate the relationship between positive life events and self-reported wellbeing (Spence et al., 2022). Individuals with a secure attachment style may be better able to recognise and appreciate positive events, therefore experiencing greater increases in wellbeing. These individuals are more likely to be in a romantic relationship than those with higher levels of attachment insecurity, although even for those not in a relationship, having a secure attachment style is associated with greater levels of psychological wellbeing and life satisfaction (MacDonald & Park, 2022; Sagone et al., 2023). Although long thought to be fixed in early childhood, attachment patterns remain somewhat dynamic and susceptible to change throughout adolescence (Jones et al., 2018; Theisen et al., 2018). This offers a powerful opportunity to positively influence lifelong trajectories. There are numerous attachment informed interventions that have been developed which adopt a variety approaches. Evidence of their efficacy, particularly with regards to sustained improvements; however, is lacking, and they currently remain underutilized (Gregory et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2023).

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction, defined as “the degree to which a person positively evaluates the overall quality of his / her life as a whole” Veenhoven (1996) (p.6), is tightly connected with the concepts of subjective wellbeing, happiness and quality of life (Medvedev & Landhuis, 2018; Pronk et al., 2016). Since it primarily relies on individuals’ personal assessments of their lives, it is inherently subjective, requiring individuals to evaluate their lives according to their personal values and priorities. However, research efforts which have sought to understand the relative influence of specific life domains on overall life satisfaction find that the quality of family and romantic relationships can have a greater impact on overall life satisfaction than other relationships (Badri et al., 2022; Milovanska-Farrington & Farrington, 2022; Nakamura et al., 2022). In Western societies, various factors are identified as significant predictors of life satisfaction. These include standards of living, household income, health status, relationship status, and mental wellbeing (Jarden et al., 2022; Kubiszewski et al., 2018; Lombardo et al., 2018; Park et al., 2020). Lower ratings of life satisfaction are associated with poorer levels of physical and mental health, chronic disease, health service utilization and premature mortality (Kim et al., 2021; Michalski et al., 2022; Rosella et al., 2018). Insights from a nationally representative study of Americans aged over 50 showed that higher ratings of life satisfaction predicted better future outcomes on a range of physical and mental health indicators (Kim et al., 2021). Improving the life satisfaction of populations is therefore an important public health objective.

National studies of life satisfaction show a U-shaped trajectory across the lifespan, characterised by declines during middle adulthood followed by a resurgence in older age. In a study of over 10,000 New Zealanders using data from the Gallup World Poll (2006 to 2017), Jarden et al. (2022) showed that life satisfaction is lowest at around 40-years of age, with living standards and household income being the strongest indicators of life satisfaction. Similarly, Park et al. (2020) demonstrated in their study of over 12,000 Australians, also using Gallup World Poll data (2005 to 2017) that life satisfaction is lowest during in the mid-thirties to mid-fifties. In another Australian study including over 30,000 participants from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey (HILDA) between 2001 and 2016, Kubiszewski et al. (2018) found life satisfaction to be lowest during in the late forties, with health, living situation and marital status being important predictors of life satisfaction. Interestingly, a similar trend is observed for levels of satisfaction with a romantic partnership throughout adulthood. One meta-analysis using data from 165 unique samples concluded that relationship satisfaction reaches its lowest point around the age of 40 (Bühler et al., 2021); comparable to life satisfaction. While it’s important to acknowledge that these findings are correlational in nature, they provide further support to results of numerous studies which find relationship status to be an important factor in how an individual rates their personal life satisfaction. These patterns suggest that fostering and maintaining fulfilling relationships may play a pivotal role in enhancing individuals’ overall life satisfaction.

Brief Review of Life Satisfaction and Attachment Studies

A growing body of literature suggests attachment style is important in life satisfaction. In early adulthood, studies of student populations find life satisfaction is positively correlated with attachment security and negatively correlated attachment insecurity (Deniz & Işik, 2010; Dugan et al., 2023). Some evidence suggests that the attachment quality of romantic relationships is a stronger predictor of life satisfaction above attachment quality with parents or peers in this age group (Guarnieri et al., 2015). This study also found that romantic attachment quality fully mediated the relationship between the mother-offspring attachment relationship and offspring life satisfaction, suggesting that secure mother-child attachments lead to more secure romantic relationships which in turn, result in higher levels of life satisfaction. Higher rates of attachment insecurity and lower rates of life satisfaction are found among young adults who identify with a sexual or gender minority group compared to those of heterosexual identity (Kardasz et al., 2023). Similarly, secure attachment style is associated with greater life satisfaction in older adulthood during the ages of approximately 60 to 70 years. Religion and hope were found to fully mediate this relationship; however, in a study of older Israeli adults, although they only partially mediated the relationship between insecure attachment and life satisfaction (Pahlevan Sharif et al., 2021). Consistent with these findings, a German study of older adults found individuals with a secure attachment style were more hopeful towards the future (Wensauer & Grossmann, 1998). Another German study of older adults found that compared to individuals with a secure attachment style, medical burden and life satisfaction were more strongly correlated with an insecure attachment style (Kirchmann et al., 2013).

Throughout adulthood, other studies find similar links between attachment style and life satisfaction. Potential mechanisms for this relationship were explored in some of these studies; for example, an Israeli study of working adults found that insecure attachment style was associated with both life satisfaction and job satisfaction, with job burnout partially mediating the relationship between attachment style and life satisfaction (Reizer, 2014). A Turkish study found that self-efficacy, self-love and compassion were mediators of life satisfaction and avoidant and secure attachment styles in adulthood, although not for anxious attachment (Deniz & Yıldırım Kurtuluş, 2023). A multinational study found higher attachment insecurity was associated with lower life satisfaction and satisfaction with singlehood, with individuals higher in attachment anxiety having a stronger desire for a partner (MacDonald & Park, 2022). A case control study of Polish women with breast cancer found higher life satisfaction was reported in women with a secure attachment style, regardless of breast cancer status (Koziińska, 2012). Lastly, a Dutch study also found attachment style was related to life satisfaction and that attachment insecurity was predicted by a range of adverse childhood experiences (Hinnen et al., 2009). These studies indicate that attachment styles impact life satisfaction across different cultures and contexts, with various mediating factors playing a role in this relationship.

Numerous studies also report a significant relationship between attachment style and closely related constructs to life satisfaction such as quality of life (Brophy et al., 2020; Darban et al., 2020) and happiness (Moghadam et al., 2016; Momeni et al., 2022). The limitation of almost all of these studies however, is that they are cross-sectional by design, and often include small, non-generalizable samples. An exception is the study by Platts et al. (2022) that prospectively examined the influence of attachment style on quality of life in a sample of over 5,000 American adults in middle to older age. Their study found that insecure attachment style longitudinally predicted poorer quality of life at a five-year follow up. In addition, they also found that insecure attachment style predicted worse mental and physical health at a 14-year follow-up. There is a need for studies that prospectively examine the influence of early adult attachment on life satisfaction in adulthood, particularly in middle adulthood where life satisfaction typically declines.

The Present Study

While studies have begun to examine the link between attachment and life satisfaction, there is a notable gap in the literature in terms of understanding the influence of attachment styles in early adult life on life satisfaction in later adulthood. The significance of early adulthood in this context stems from the evidence that attachment styles are more malleable up to approximately this period in life (Jones et al., 2018; Theisen et al., 2018) and therefore potentially a critical period for attachment development that could have lifelong influences. Notably, existing studies have shown that life satisfaction tends to dip during mid-life, yet research efforts have typically paid greater attention to factors influencing life satisfaction in later adulthood (Cheng et al., 2022; Khodabakhsh, 2022). In contrast, a significant portion of research exploring the relationship between attachment and life satisfaction has centred primarily on early, or later adulthood. Much of the existing research has focused on specific demographic groups, such as students, which leaves questions about the generalisability of these findings. This study seeks to bridge these gaps by drawing upon data from a longitudinal birth cohort study to explore the relationship between attachment styles and life satisfaction over nearly a decade of follow-up. Given life satisfaction is closely connected to physical and mental health, it is vital to explore ways in which life satisfaction can be enriched earlier in adulthood.

This study seeks to address these gaps by drawing upon data from a longitudinal birth cohort. Its primary aim is to expand the current body of research on attachment and life satisfaction through a longitudinal investigation into how attachment patterns observed during emerging adulthood (at 21-years) is associated with life satisfaction in later adulthood (at 30-years) in a large community sample. The study will employ a multi-dimensional assessment of attachment to simultaneously account for both the degree of attachment security and insecurity across five distinct domains of attachment to potentially illuminate important elements of attachment that could be targeted through intervention.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

This study utilised data from a prospective birth cohort of mothers and their offspring who received antenatal care at an urban Australian hospital between 1981 and 1984. Around 50% of all births in the region during this time occurred at this facility. Pregnant women attending their first antenatal appointment were consecutively invited to participate in the study. Of the 8,556 private and public patient pregnant women invited to participate in the study, 8,458 (98.9%) consented. Participants enrolled into the study provided informed written consent (see Najman et al. (2005; 2015) for further details). Baseline data were collected on a total of 7,223 singleton, live-birth offspring and their mothers. Mothers and offspring were followed prospectively when offspring were six-months, five, 14, 21 and 30-years of age. The 21-year follow up occurred from 2001 to 2004. Ethical approval for the 21-year follow-up for this study was granted by the relevant university and hospital Human Research Ethics Committees.

Measures

Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ)

At the 21-year follow up, offspring attachment styles were assessed using the Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ) (Feeney et al., 1994). The ASQ is a 40 item self-report measure designed for young adults and/or those without experience of romantic relationships. Items are framed as statements such as “I find it hard to trust other people” and “I often feel left out or alone”, which participants responded to on a 6-point Likert scale (“totally disagree” to “strongly disagree”). Items were grouped into five subscales: (1) confidence (in self and others) (CON), (2) discomfort with closeness (DWC), (3) relationships as secondary (compared with achievements) (RAS), (4) need for approval (related to fear of rejection) (NFA), and (5) preoccupation with relationships (PWR). For each subscale a mean score was calculated. This study utilises a 33-item short form of the ASQ, which has been previously validated by confirmatory factor analysis in the study sample (see Supplementary Table 1 for a full list of items).

Life Satisfaction

At the 30-year follow up, participants responded to three items: life satisfaction (how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?), happiness (how would you say you feel these days?) and quality of life (how would you rate your overall quality of life these days?) on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from (4) (very satisfied / very happy / excellent) to (1) (very dissatisfied / very unhappy / poor). Responses to the three items were combined to yield an overall ‘satisfaction with life’ score ranging from a possible lowest score of 3 to a highest possible score of 12. High internal consistency was found for the three life satisfaction questions (Cronbach’s Alpha [α] = 0.89).

Covariates

Potential covariates collected at the 21-year follow-up considered for inclusion in the analyses included sex (male / female), level of education (incomplete high school / complete high school / diploma or certificate / post high school education), relationship status (single / partner – living separately / partner – living together), living arrangement ((live with parents / own your accommodation [outright or with a mortgage] / rent / other), age of leaving the parental home (≤ 16/ 17 / 18 / 19 / 20+), biological children in own care (yes / no), weekly income ([gross income including welfare benefits] no income / <$200 / $200 - $499 / $500 - $799 / $800+ [AUD]).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using R v4.1.1 (R Core Team, 2023). A total sample of 2,088 participants (51.9% of the original 7,233 participants recruited at birth) had less than 10% missing data on the ASQ and no missing data for each of the three outcome variables at the 30-year follow up. Of these, 142 (6.8%) participants had between one and three missing items (≤ 10%) on the ASQ. Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test showed evidence of systematic missingness in our data (χ2 (1,480) = 1,708, p < 0.001). Data were imputed using a linear regression based simple imputation method whereby missing values are predicted using observed responses.

Differences in 21-year characteristics among those retained in the study and those lost to follow-up at the 30-year follow-up were examined using Welch’s two sample t-test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi square tests for categorical variables. Univariable linear regressions were run for each variable individually against levels of life satisfaction at age 30-years. Multivariable linear regression was used to assess the relationship between attachment domains of the ASQ at 21-years, adjusting for covariates. Collinearity was not detected between any of the five ASQ attachment domains and they were subsequently included within the one multivariate model.

Results

Differences in 21-year characteristics between those retained in the current study (n = 2,088) compared with those lost to follow-up at 30-years (n = 1,627) are shown in Table 1. Statistically significant differences were found between the two groups across all covariates, with those lost to follow up being more likely to be male (57.3% vs. 38.7%), have an incomplete high school education (27.8% vs. 15.0%), earn less than $200 per week (26.5% vs. 20.9%), have moved out of home at 16-years of age or younger (14.6% vs. 8.8%) and not have a partner (51.2% vs. 45.8%).

For participants included in the current study, the majority were female (n = 1,279, 61.3%), who had completed high school education (n = 1,777, 56.8%), and at 21-years were single (n = 953, 45.8%), had never left the parental home (n = 959, 46.1%), earned a weekly income of $200 to $499 AUD (n = 1,010, 49.5%) and had no biological children in their care (n = 1,925, 92.5%).

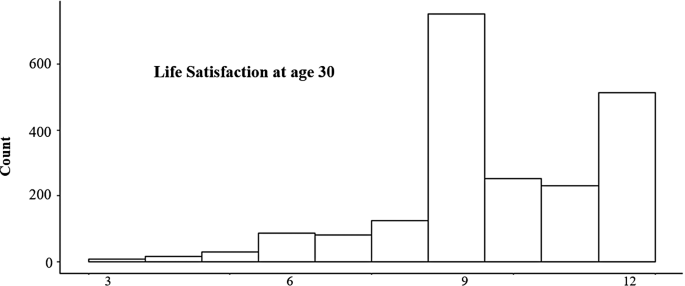

Figure 1 shows the distribution of total life satisfaction scores at age 30. A little over one-third of the 2,088 participants included in the current study reported a life satisfaction score of 9 out of a possible 12 (n = 752, 36.0%), and one-quarter of participants (n = 512, 24.5%) reported a maximum score of 12.

Linear Regression

Table 2 presents the results of the univariable and multivariable associations between each separate predictor and life satisfaction at age 30. In the univariable analyses, each of the five attachment domains at age 21 were individually associated with life satisfaction at age 30, with confidence being the domain that was most strongly associated (β = 0.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.68–0.90, p < 0.001). Of the seven covariates included in the analyses, participant sex and living arrangements were not independently statistically significantly associated with life satisfaction and were not included in the multivariate analysis.

After adjustments for all attachment domains and covariates, confidence remained the attachment domain most strongly associated with life satisfaction (β = 0.41, 95% CI 0.25–0.56, p < 0.001). Need for approval was the only other attachment domain to remain statistically significantly associated with life satisfaction (β = -0.17, 95% CI -0.30 – -0.04, p < 0.001).

Covariates which remained also significantly associated with life satisfaction included: having no income (compared to earning $200 - $499AUD per week) (β = -0.66, 95% CI -1.03 -0.29, p < 0.001) or low income (β = -0.22, 95% CI -0.40 -0.04, p < 0.018), leaving the parental home at 16-years or younger (compared to currently living in the parental home) (β = -0.43, 95% CI -0.74 to -0.12, p = 0.007), caring for biological children (compared to not caring for biological children) (β =-0.49, 95% CI -0.49 to -0.18, p = 0.002) and having a partner (compared to being single) (not cohabiting: β = 0.41, 95% CI 0.23–0.60, p < 0.001; cohabiting: β = 0.26, 95% CI 0.05–0.47, p < 0.014).

Discussion

The current study examined the association between attachment style in young adults (21-years) and life satisfaction at age 30, utilising a dimensional measure of attachment, encompassing five attachment domains reflecting security, avoidance, and anxiety in a large community sample. The study has several key findings. First, confidence in self and others at 21 years emerged as a significant predictor of life satisfaction at age 30, even after accounting for the degree of endorsement on domains of attachment insecurity and important social-demographic factors such as relationship status, income and education. Second, greater need for approval increased the likelihood of reporting low life satisfaction, albeit to a lesser extent than confidence. Finally, preoccupation with relationships and insecure-avoidant attachment assessed by discomfort with closeness and relationships as secondary subscales, were not associated with future life satisfaction when accounting for other attachment domains.

While previous research has established a link between attachment and life satisfaction in university students (Tepeli Temiz & Tarı Cömert, 2018), and adults (Deniz & Yıldırım Kurtuluş, 2023), our findings suggest that attachment style in early adulthood is associated with life satisfaction a decade later. The current results underscore the importance of considering an individual’s level of confidence in self and others, for this is a component of attachment security and a secure internal working model of interpersonal relationships, regardless of the co-occurrence of patterns of attachment anxiety or avoidance. Higher scores on the confidence subscale reflects a positive internal working model characterised by high self-worth, trust in others and a general confidence in interpersonal relating. Our findings therefore suggest that having a positive representation of oneself and others is associated with later life satisfaction, independent of most features of attachment insecurity (discomfort with closeness, relationships as secondary and preoccupation with relationships). Need for approval was the only domain of attachment insecurity that was significantly associated with life later satisfaction. This finding aligns with previous research finding that individuals exhibiting a high need for approval by others is negatively correlated with life satisfaction in adulthood (Fowler et al., 2018). Importantly, early adult attachment remained independently associated with later life satisfaction even after accounting for a range of important social-demographic factors, suggesting that modification of attachment style in emerging adulthood could enhance life satisfaction further into adulthood.

In terms of covariates, not having an income at age 21 was most strongly negatively associated with life satisfaction at age 30, followed by caring for biological children at age 21 and leaving the parental home by age 16. One nationally representative Australian study found that life satisfaction decreases in the years following child-bearing, with declines in satisfaction with leisure, health and partnership explaining the overall decrease (Aassve et al., 2021). The finding that childbearing in early adulthood is associated with lower life satisfaction almost 10-years later in our study warrants exploration around the ways in which young people who enter parenthood can be better supported to have greater life satisfaction. Compared to those still living in the parental home, individuals who left the parental home by age 16 or younger were at a significant risk of lower life satisfaction at age 30. Interestingly however, the effect of leaving the parental home at age 17 or above was not significant. Research shows that young Australians who have experienced marginalization such as early life disadvantage, social isolation and financial hardship, are more likely to leave home prior to the age of 18, and that for those who do, this marginalization persists during the 10-years following (Cruwys et al., 2013). Another Australian study shows that for young people who leave home for reasons other than to live with a partner, are more likely to be less satisfied with the quality of the relationships with their parents (Qu & De Vaus, 2015). Experiences of childhood abuse and household dysfunction, for example, are significant predictors of lower life satisfaction in adulthood (Mosley-Johnson et al., 2019) and these adversities are also likely to contribute to an early departure from the parental home.

Individuals who reported having a partner but not cohabiting with their partner on the other hand, were more likely to report greater life satisfaction compared to those who were single, as too were those living with a partner, although the association of this relationship was weaker in magnitude. Where previous studies have found that being in a non-cohabiting relationship is associated with lower life satisfaction (Bucher et al., 2019), the positive effect of not cohabiting with a partner in the current study may be explained by factors relating to the age of participants who are more likely to be still living in the parental home and may benefit from maintaining the autonomy to independently navigate the transition into adulthood and pursue individual goals whilst simultaneously receiving support and companionship from a romantic partner. This finding suggests that consideration of the context of intimate relationship such as the underlying mechanisms and contextual factors (e.g. age, relationship quality and duration, desire for a partner) that might explain the relationship between relationship status and life satisfaction (Roy et al., 2023; Stahnke & Cooley, 2021), may be an important factor when examining the effects of relationships in the context of life satisfaction. The level of contentment with being single is also an important consideration of the relationship between attachment style and life satisfaction. MacDonald and Park (2022) found that secure attachment was a protective factor for life satisfaction for non-partnered individuals, suggesting that these people are better equipped to meet their needs for emotional connection through non-romantic relationships. Researchers should be encouraged to incorporate information on relationship context when examining relationship status in future studies on life satisfaction and attachment.

Incomplete high school education was negatively associated with later life satisfaction in the current study, although this relationship became non-significant after controlling for other variables, including income. A recent study examining data from 24 nations showed that income attenuated the relationship between higher education and life satisfaction (Araki, 2022), with similar results found in other studies which show that education is not a significant predictor of life satisfaction when accounting for income (Hennig & Laier, 2023; Jarden et al., 2022) suggesting that the association between education and with life satisfaction can be explained by the earning potential relevant to the level of education attainment. While higher income in early adulthood was not associated with later life satisfaction in the current study, having no income emerged as the strongest predictor in the model of life satisfaction almost 10-years later. The absence of contextual information regarding the financial and living circumstances of this group, such as whether they were being financially supported by parents, experienced a temporary lapse in employment or endured chronic poverty for example, makes it is difficult to draw clear interpretations. Regardless, these add to the literature base that evidence a strong link between income and life satisfaction by demonstrating a longitudinal adverse effect of having no income in early adult life on life satisfaction later into adulthood.

The link between attachment, interpersonal relationships, and life satisfaction is well established, yet the effectiveness of attachment informed interventions in increasing life satisfaction remains relatively unknown. Greenman and Johnson (2022) suggest that attachment is a valuable framework through which to understand links between loneliness, social disconnection and health, all of which are linked to life satisfaction. Currently, there exists a broad range of attachment-based interventions that aim to promote healthy attachment styles during adolescence (Kobak et al., 2015) that enhance close relationships, improve interpersonal communication, and foster a sense of connectedness more broadly (Greenman & Johnson, 2022; Kobak & Bosmans, 2019). Attachment is shown to be more stable in adulthood and therefore more difficult to modify (Fraley, 2019) thus, interventions targeting adolescence may be a critical window in which to intervene. Interventions with an attachment focus may have potential in improving life satisfaction in adulthood, given that improving interpersonal communication is associated with better psychological health and wellbeing (Mukherjee, 2017; Oliveira et al., 2022). Approaches to increasing relational confidence and attachment security can be implemented in a range of settings that extend beyond 1:1 therapy (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2020). Attachment style can affect educational outcomes (Wang et al., 2021), work performance (Greškovičová & Lisá, 2023) and health (Pietromonaco & Beck, 2019)—all of which are important factors in life satisfaction.

In childhood education, teachers serve as an attachment figure by providing a supportive and reassuring environment to learn through taking risks and making mistakes (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2020). Preliminary evidence supports the use of attachment based interventions to enhancing teacher-child relationships (Spilt & Koomen, 2022). In healthcare, patient attachment style is associated with service utilization and treatment outcomes (Jimenez, 2016; Meng et al., 2015). Health providers serve attachment related functions through provision of a safe haven during times of distress and also as a secure base whereby they can facilitate increases in health related confidence (Maunder & Hunter, 2016). Attachment informed interventions are also recommended for the workplace. The use of security priming interventions for those who are in leadership roles for example, are suggested to increase secure base behaviours and create secure relationships in the workplace (Yip et al., 2018). Public health and policy initiatives also offer important opportunities to foster secure attachment trajectories. Cassidy et al. (2013) argue for example, that parental leave, child care and flexible work policies should “recognize child care as a prime societal concern” (p.15) based on a substantial literature base for the importance of attachment theory in parenting and child development.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first longitudinal study to examine the associations between attachment styles in young adults with later life satisfaction. Furthermore, the large, community-based sample enhances the generalizability of the findings. The utilization of a dimensional measure of attachment that captures broad inner working models of interpersonal relationships, rather than focusing on a specific person of reference, allows the association between specific attachment styles and adult life satisfaction. However, it is important to note that the confidence subscale used in our study does not fully assess all dimensions of attachment security (Justo-Núñez et al., 2022), and therefore should be interpreted within this context. A further limitation of the study is the measurement of life satisfaction through a brief composite measure of happiness, quality of life, and satisfaction with life. Single item measures of life satisfaction; however, are shown to produce similar results to the use of longer validated scales (Cheung & Lucas, 2014). The current study used three items that demonstrated good internal consistency which have been used in previous studies (Lee et al., 2021). The lack of detailed insights and contextual factors that may have influenced the responses; however, is a potential limitation (Ruggeri et al., 2020). Another limitation is the considerable attrition rate, with approximately two-thirds of the original sample lost to follow up at age 30. Although significant differences were found between participants retained in the sample and those who were lost to follow-up, previous research suggests that differential attrition rarely affects estimates of associations (Saiepour et al., 2019). None the less, interpreting the findings of the current study within the context of the study sample is required.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study identifies associations between young adult attachment styles and life satisfaction almost 10-years later. This study provides evidence that an inner working model of interpersonal relationships characterised by confidence in self and support from others in early adulthood is associated with an increased life satisfaction at age 30, while a higher need for approval was associated with lower life satisfaction. Having a low, or no income at age 21, leaving the parental home at 16-years of age or younger, and caring for children at age 21 were risk factors for lower life satisfaction at age 30, while having a partner at age 21 was associated with higher life satisfaction. Optimising life satisfaction is an important public health objective and is integral to overall health and wellbeing. Application of attachment-informed interventions that cultivate secure internal working models of interpersonal relationships and particularly increasing confidence in relating with others during adolescence and early adulthood is proposed as a potential strategy to improve life satisfaction in middle adulthood.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any competing interests to report.

References

Aassve, A., Luppi, F., & Mencarini, L. (2021). A first glance into the black box of life satisfaction surrounding childbearing. Journal of Population Research, 38(3), 307–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-021-09267-z.

Araki, S. (2022). Does Education make people happy? Spotlighting the overlooked Societal Condition. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(2), 587–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00416-y.

Badri, M. A., Alkhaili, M., Aldhaheri, H., Yang, G., Albahar, M., & Alrashdi, A. (2022). Exploring the reciprocal relationships between happiness and life satisfaction of working adults-evidence from Abu Dhabi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063575.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol, 61(2), 226–244. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226.

Brophy, K., Brähler, E., Hinz, A., Schmidt, S., & Körner, A. (2020). The role of self-compassion in the relationship between attachment, depression, and quality of life. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 45–52. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165032719312686?via%3Dihub.

Bucher, A., Neubauer, A. B., Voss, A., & Oetzbach, C. (2019). Together is Better: Higher committed relationships increase life satisfaction and reduce loneliness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(8), 2445–2469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0057-1.

Bühler, J. L., Krauss, S., & Orth, U. (2021). Development of relationship satisfaction across the life span: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(10), 1012–1053. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000342.

Cassidy, J., Jones, J. D., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt2), 1415–1434. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579413000692.

Cheng, A., Leung, Y., & Brodaty, H. (2022). A systematic review of the associations, mediators and moderators of life satisfaction, positive affect and happiness in near-centenarians and centenarians. Aging & Mental Health, 26(4), 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1891197.

Cheung, F., & Lucas, R. E. (2014). Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: Results from three large samples. Quality of Life Research, 23(10), 2809–2818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0726-4.

R Core Team (2023). A language and environment for statistical computing. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Cruwys, T., Berry, H., Cassells, R., Duncan, A., O’Brien, L., Sage, B., & Souza, D. (2013). G. Marginalised australians: Characteristics and predictors of exit over ten years 2001-10.

Darban, F., Safarzai, E., Koohsari, E., & Kordi, M. (2020). Does attachment style predict quality of life in youth? A cross-sectional study in Iran. Health Psychology Research, 8(2).

Deniz, M. E., & Işik, E. (2010). Positive and negative affect, life satisfaction, and coping with stress by attachment styles in Turkish students. Psychological Reports, 107(2), 480–490.

Deniz, M. E., & Yıldırım Kurtuluş, H. (2023). Self-Efficacy, Self-Love, and Fear of Compassion Mediate the Effect of Attachment Styles on Life Satisfaction: A Serial Mediation Analysis. Psychological reports, 00332941231156809. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941231156809.

Dugan, K. A., Khan, F., & Fraley, R. C. (2023). Dismissing attachment and global and daily indicators of Subjective Well-Being: An experience Sampling Approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49(8), 1197–1212. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672221089781.

Feeney, J. A., Noller, P., & Hanrahan, M. (1994). Assessing adult attachment.

Fowler, S., Davis, L., Both, L., & Best, L. (2018). Personality and perfectionism as predictors of life satisfaction: The unique contribution of having high standards for others. FACETS, 3, 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2017-0084.

Fraley, R. C. (2019). Attachment in Adulthood: Recent developments, emerging debates, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102813.

Greenman, P. S., & Johnson, S. M. (2022). Emotionally focused therapy: Attachment, connection, and health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 146–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.06.015.

Gregory, M., Kannis-Dymand, L., & Sharman, R. (2020). A review of attachment‐based parenting interventions: Recent advances and future considerations. Australian Journal of Psychology, 72(2), 109–122.

Greškovičová, K., & Lisá, E. (2023). Beyond the global attachment model: Domain- and relationship-specific attachment models at work and their functions. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1158992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1158992.

Guarnieri, S., Smorti, M., & Tani, F. (2015). Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging Adulthood. Social Indicators Research, 121(3), 833–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0655-1.

Gustavson, K., Røysamb, E., Borren, I., Torvik, F. A., & Karevold, E. (2016). Life satisfaction in Close relationships: Findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(3), 1293–1311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9643-7.

Heinsch, M., Wells, H., Sampson, D., Wootten, A., Cupples, M., Sutton, C., & Kay-Lambkin, F. (2022). Protective factors for mental and psychological wellbeing in Australian adults: A review. Mental Health & Prevention, 25, 200192.

Hennig, M., & Laier, B. (2023). Social Resources and Life satisfaction: Country-Specific effects? International Journal of Sociology, 53(1), 36–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2022.2134614.

Hinnen, C., Sanderman, R., & Sprangers, M. A. G. (2009). Adult attachment as mediator between recollections of childhood and satisfaction with life. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.600.

Jarden, R. J., Joshanloo, M., Weijers, D., Sandham, M. H., & Jarden, A. J. (2022). Predictors of life satisfaction in New Zealand: Analysis of a National dataset. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095612.

Jimenez, X. F. (2016). Attachment in medical care: A review of the interpersonal model in chronic disease management. Chronic Illness, 13(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395316653454.

Jones, J. D., Fraley, R. C., Ehrlich, K. B., Stern, J. A., Lejuez, C. W., Shaver, P. R., & Cassidy, J. (2018). Stability of attachment style in adolescence: An empirical test of alternative developmental processes. Child Development, 89(3), 871–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12775.

Justo-Núñez, M., Morris, L., & Berry, K. (2022). Self‐report measures of secure attachment in adulthood: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(6), 1812–1842. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2756.

Kardasz, Z., Gerymski, R., & Parker, A. (2023). Anxiety, attachment styles and life satisfaction in the Polish LGBTQ + community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(14), 6392. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/14/6392.

Kaufman, V., Rodriguez, A., Walsh, L. C., Shafranske, E., & Harrell, S. P. (2022). Unique Ways in which the Quality of Friendships Matter for life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(6), 2563–2580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00502-9.

Khodabakhsh, S. (2022). Factors affecting life satisfaction of older adults in Asia: A systematic review. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(3), 1289–1304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00433-x.

Kim, E. S., Delaney, S. W., Tay, L., Chen, Y., Diener, E. D., & Vanderweele, T. J. (2021). Life satisfaction and subsequent physical, behavioral, and Psychosocial Health in older adults. Milbank Quarterly, 99(1), 209–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12497.

Kirchmann, H., Nolte, T., Runkewitz, K., Bayerle, L., Becker, S., Blasczyk, V., Lindloh, J., & Strauss, B. (2013). Associations between adult attachment characteristics, Medical Burden, and life satisfaction among older primary care patients. Psychology and Aging, 28, 1108–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034750.

Kobak, R., & Bosmans, G. (2019). Attachment and psychopathology: A dynamic model of the insecure cycle. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 76–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.018.

Koziińska, B. (2012). [Attachment and functioning of women with breast cancer]. Annales Academiae Medicae Stetinensis, 58(2), 22–30. (Przywiazanie a funkcjonowanie kobiet z choroba nowotworowa piersi.).

Kubiszewski, I., Zakariyya, N., & Costanza, R. (2018). Objective and subjective indicators of life satisfaction in Australia: How well do people perceive what supports a good life? Ecological Economics, 154, 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.08.017.

Lee, C. W., Lin, L. C., & Hung, H. C. (2021). Art and cultural participation and life satisfaction in adults: The role of physical health, mental health, and interpersonal relationships. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 582342.

Lewczuk, K., Kobylińska, D., Marchlewska, M., Krysztofiak, M., Glica, A., & Moiseeva, V. (2021). Adult attachment and health symptoms: The mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties. Current Psychology, 40(4), 1720–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0097-z.

Lombardo, P., Jones, W., Wang, L., Shen, X., & Goldner, E. M. (2018). The fundamental association between mental health and life satisfaction: Results from successive waves of a Canadian national survey. Bmc Public Health, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5235-x.

MacDonald, G., & Park, Y. (2022). Associations of attachment avoidance and anxiety with life satisfaction, satisfaction with singlehood, and desire for a romantic partner.Personal Relationships, 29(1), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12416.

Manning, R. P. C., Dickson, J. M., Palmier-Claus, J., Cunliffe, A., & Taylor, P. J. (2017). A systematic review of adult attachment and social anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 211, 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.020.

Martino, J., Pegg, J., & Frates, E.P. (2017). The connection prescription: Using the power of social interactions and the deep desire for connectedness to empower health and wellness. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 11(6), 466–475.

Maunder, R. G., & Hunter, J. J. (2016). Can patients be ‘attached’ to healthcare providers? An observational study to measure attachment phenomena in patient-provider relationships. British Medical Journal Open, 6(5), e011068. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011068.

Medvedev, O. N., & Landhuis, C. E. (2018). Exploring constructs of well-being, happiness and quality of life. PeerJ, 6, e4903. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4903.

Meng, X., D’Arcy, C., & Adams, G. C. (2015). Associations between adult attachment style and mental health care utilization: Findings from a large-scale national survey. Psychiatry Research, 229(1), 454–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.092.

Michalski, C. A., Diemert, L. M., Hurst, M., Goel, V., & Rosella, L. C. (2022). Is life satisfaction associated with future mental health service use? An observational population-based cohort study. British Medical Journal Open, 12(4), e050057. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050057.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P., David, S. A., Boniwell, I., & Ayers, A. (2013). Adult attachment and happiness: Individual differences in the experience and consequences of positive emotions. The Oxford Handbook of Happiness, 834–846.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, & R, P. (2020). Enhancing the Broaden and Build cycle of attachment security in Adulthood: From the Laboratory to Relational contexts and Societal systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062054.

Milovanska-Farrington, S., & Farrington, S. (2022). Happiness, domains of life satisfaction, perceptions, and valuation differences across genders. Acta Psychologica, 230, 103720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103720.

Moghadam, M., Rezaei, F., Ghaderi, E., & Rostamian, N. (2016). Relationship between attachment styles and happiness in medical students. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary care, 5(3), 593. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5290766/pdf/JFMPC-5-593.pdf.

Momeni, K., Amani, R., Janjani, P., Majzoobi, M. R., Forstmeier, S., & Nosrati, P. (2022). Attachment styles and happiness in the elderly: The mediating role of reminiscence styles. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03053-z.

Mosley-Johnson, E., Garacci, E., Wagner, N., Mendez, C., Williams, J. S., & Egede, L. E. (2019). Assessing the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and social well-being: United States Longitudinal Cohort 1995–2014. Quality of Life Research, 28(4), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2054-6.

Mukherjee, I. (2017). Enhancing positive emotions via positive interpersonal communication: An Unexplored Avenue towards Well-being of mankind. Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.15406/jpcpy.2017.07.00448.

Najman, J. M., Bor, W., O’Callaghan, M., Williams, G. M., Aird, R., & Shuttlewood, G. (2005). Cohort Profile: The Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP). International Journal of Epidemiology, 34(5), 992–997. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyi119.

Najman, J. M., Alati, R., Bor, W., Clavarino, A., Mamun, A., McGrath, J. J., McIntyre, D., O’Callaghan, M., Scott, J., Shuttlewood, G., Williams, G. M., & Wray, N. (2015). Cohort Profile Update: The mater-university of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP). International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(1), 78–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu234.

Nakamura, J. S., Delaney, S. W., Diener, E., VanderWeele, T. J., & Kim, E. S. (2022). Are all domains of life satisfaction equal? Differential associations with health and well-being in older adults. Quality of Life Research, 31(4), 1043–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02977-0.

Nottage, M. K., Oei, N. Y. L., Wolters, N., Klein, A., Van der Heijde, C. M., Vonk, P., Wiers, R. W., & Koelen, J. (2022). Loneliness mediates the association between insecure attachment and mental health among university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 185, 111233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111233.

Oliveira, D., Carter, T., & Aubeeluck, A. (2022). Editorial: Interpersonal wellbeing across the Life Span. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 840820. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.840820.

Pahlevan Sharif, S., Amiri, M., Allen, K. A., Nia, S., Khoshnavay Fomani, H., Matbue, F. H., Goudarzian, Y., Arefi, A. H., Yaghoobzadeh, S., A., & Waheed, H. (2021). Attachment: The mediating role of hope, religiosity, and life satisfaction in older adults. Health Quality of Life Outcomes, 19(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01695-y.

Park, J., Joshanloo, M., & Scheifinger, H. (2020). Predictors of life satisfaction in Australia: A study drawing upon annual data from the Gallup World Poll. Australian Psychologist, 55(4), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12441.

Pietromonaco, P. R., & Beck, L. A. (2019). Adult attachment and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.004.

Platts, L. G., Norbrian, A., A., & Frick, M. A. (2022). Attachment in older adults is stably associated with health and quality of life: Findings from a 14-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Aging & Mental Health, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2022.2148157.

Pronk, N., Ma, Kottke, K., Lowry, T., Katz, M., Gallagher, A., Knudson, S., Rauri, S., Tillema, J., & Mpa. (2016). Concordance between life satisfaction and six elements of well-being among respondents to a Health Assessment Survey, HealthPartners employees, Minnesota, 2011. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.160309.

Qu, L., & de Vaus, D. (2015). Life satisfaction across life course transitions. Journal of the Home Economics Institute of Australia, 22(2), 15–27.

Reizer, A. (2014). Influence of employees’ attachment styles on their life satisfaction as mediated by job satisfaction and burnout. The Journal of Psychology, 149, 141217142405003. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2014.881312.

Rosella, L. C., Fu, L., Buajitti, E., & Goel, V. (2018). Death and chronic Disease Risk Associated with Poor Life satisfaction: A Population-based Cohort Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(2), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy245.

Roy, L. H., Park, Y., & MacDonald, G. (2023). Age moderates the link between relationship desire and life satisfaction among singles. Personal Relationships.

Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., Matz, S., & Huppert, F. A. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y.

Sagone, E., Commodari, E., Indiana, M. L., & La Rosa, V. L. (2023). Exploring the association between attachment style, Psychological Well-Being, and relationship status in young adults and Adults—A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Investigation in Health Psychology and Education, 13(3), 525–539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13030040.

Saiepour, N., Najman, J. M., Ware, R., Baker, P., Clavarino, A. M., & Williams, G. M. (2019). Does attrition affect estimates of association: A longitudinal study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 110, 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.12.022.

Sherman, L. J., Rice, K., & Cassidy, J. (2015). Infant capacities related to building internal working models of attachment figures: A theoretical and empirical review. Developmental Review, 37, 109–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2015.06.001.

Spence, R., Kagan, L., Nunn, S., Bailey-Rodriguez, D., Fisher, H. L., Hosang, G. M., & Bifulco, A. (2022). The moderation effect of secure attachment on the relationship between positive events and wellbeing. PsyCh Journal, 11(4), 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.546.

Spilt, J. L., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2022). Three decades of Research on Individual Teacher-Child relationships: A chronological review of Prominent attachment-based themes. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.920985.

Stahnke, B., & Cooley, M. (2021). A Systematic Review of the Association between Partnership and Life satisfaction. The Family Journal, 29(2), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720977517.

Tepeli Temiz, Z., & Tarı Cömert, I. (2018). The relationship between satisfaction with life, attachment styles, and psychological resilinece in university students. https://doi.org/10.5350/DAJPN2018310305.

Theisen, J. C., Fraley, R. C., Hankin, B. L., Young, J. F., & Chopik, W. J. (2018). How do attachment styles change from childhood through adolescence? Findings from an accelerated longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.04.001.

Veenhoven, R. (1996). The study of life-satisfaction. In. Eötvös University. http://hdl.handle.net/1765/16311.

Wang, Q., Peng, S., & Chi, X. (2021). The relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems in Chinese adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 644222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644222.

Wensauer, M., & Grossmann, K. E. (1998). Principles of attachment theory in subjective life satisfaction and individual orientation to the future in advanced adulthood. Journal of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, 31(5), 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003910050060.

Wright, B., Fearon, P., Garside, M., Tsappis, E., Amoah, E., Glaser, D., Allgar, V., Minnis, H., Woolgar, M., Churchill, R., McMillan, D., Fonagy, P., O’Sullivan, A., & McHale, M. (2023). Routinely used interventions to improve attachment in infants and young children: A national survey and two systematic reviews. Health Technology Assessment, 27(2), 1–226. https://doi.org/10.3310/ivcn8847.

Yip, J., Ehrhardt, K., Black, H., & Walker, D. O. (2018). Attachment theory at work: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2204.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blake, J.A., Thomas, H.J., Pelecanos, A.M. et al. Attachment in Young Adults and Life Satisfaction at Age 30: A Birth Cohort Study. Applied Research Quality Life (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10297-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10297-x