Abstract

This study investigates the outcomes of online Service-Learning (SL) in Philippine partner communities, addressing a literature gap on predominantly face-to-face (f2f) SL. Applying the Conceptual Framework of Community Impacts Arising from Service-Learning, it employs a mixed-method convergent design to assess the benefits, drawbacks, and influential factors of online SL’s effectiveness (CARE, TIP, and FEAR). Data, sourced from 101 survey participants across 46 Community Partner Organizations (CPOs) in affiliation with Ateneo de Manila University, is complemented by the insights derived from 22 comprehensive interviews with key community contact persons. Findings reveal that online SL bolsters CPOs’ missions, enhance resources, facilitates knowledge transfer, and yields positive outcomes. However, barriers such as Time management challenges, Infrastructure and technical hurdles, and Participation obstacles (TIP), along with its consequent drawbacks such as difficulty in providing timely and effective Feedback, disparity in varying levels of Effort displayed by students, erosion of Authentic relationships in prolonged virtual engagements, and Repetitiveness and nonfulfillment concerns (FEAR) were identified as challenges. Despite these, Collaborative coordination, Active communication, Responsiveness to CPO’s needs, and Engaging online environment (CARE) were recognized as key enablers. This research highlights the significance of examining the outcomes of online SL from the perspective of community partners, informing best practices for implementation, and cultivating effective online SL collaborations that can be adapted across various countries with similar contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Service-Learning (SL) integrates academic study with community service guided by reciprocal relations and systematic reflection (Bringle, 2015; Bringle & Hatcher, 2009). Online SL is a unique mode of service-learning that takes place in a completely online environment, enabling students to work with partner communities remotely using information and communication technology (ICT) platforms (Marcus et al., 2020; Waldner et al., 2012). Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, online SL has become an essential adaptation for higher education institutions (HEIs) worldwide (Dapena et al., 2022; Schmidt, 2021). While online SL offers numerous advantages, such as improved accessibility and flexibility (Waldner et al., 2012), its outcomes on partner communities remain unclear. Outcomes in this study refer to the instantaneous benefits or drawbacks of online SL projects on the partner communities involved. These outcomes may encompass direct or short-term effects or changes on the community partner’s knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, or practices. In the development studies literature, these outcomes serve as early indicators of longer-term effects, and they are also used to help inform decisions about how to adjust or refine an intervention (Belcher & Palenberg, 2018).

In contrast, studies on the various effects of SL on partner communities in face-to-face (f2f) settings have been well documented, particularly in HEIs in the United States of America (USA), where SL originated (Kung & Liu, 2018; Ma & Chan, 2013). For instance, Driscoll et al. (1996) found that hosting SL students from Portland State University had a positive effect on community organizations’ capacity to serve beneficiaries, improved social and economic benefits for the organizations, and provided new insights about program operations. In another study, Sandy and Holland (2006) investigated the effect of SL projects on 99 communities in California that partnered with eight HEIs in their area. Their study reported six benefits of SL projects to partner communities, including direct benefits from specific outcomes, volunteer work, staff and organizational development, improved management systems, strengthened links with different groups, and transformational knowledge generation. Recent studies by Kindred (2020), Towey and Bernstein (2019), and Trager (2020) also support these findings among non-profit partner organizations of various HEIs in the USA.

In the Philippines, studies on the effect of SL on partner communities are limited, and most question the effectiveness of such programs due to project design flaws and lack of sustainability (Dela Cruz et al., 2013), student-centric and charity-driven approaches (Sampa, 2012), the inability to address the dire socio-economic conditions of partner communities (Miciano, 2006), and limited participation and voice of partner communities in project planning (Abenir, 2019). Recommendations have been made to address these issues, such as giving enough time for students to get to know partner communities and partnering with external agents of change for sustainability (Dela Cruz et al., 2013), implementing development-oriented SL projects (Sampa, 2012), addressing socio-economic factors affecting community participation in SL programs (Miciano, 2006), and strengthening social capital through community organizing to empower partner communities to take ownership of SL initiatives (Abenir, 2019). However, all of these studies were conducted in the context of f2f SL engagements.

Therefore, this research aims to address the gap in knowledge concerning the outcomes of online SL engagements in partner communities, as well as investigate the enablers and barriers that influence these outcomes. Gaining insight into these outcomes is vital for developing online SL programs that empower communities while mitigating potential drawbacks. As digital learning and remote collaboration become increasingly prevalent, understanding the outcomes of online SL is essential. This study can offer valuable guidance for designing inclusive online SL programs that cater to community needs and can potentially be adapted across various countries with similar contexts.

Navigating the Evolving Landscape of Face-to-Face and Online Service-Learning

The literature on SL has evolved over the years to highlight its transformative potential for communities. Most existing works, such as those by Kindred (2020), Towey and Bernstein (2019), and Trager (2020), focus on the benefits accrued through traditional, face-to-face (f2f) SL models, examining how these engagements enhance community capacities, social capital, and well-being. This also supported by Matthews (2019) who explored how community partners experience SL in a South African university, finding that community partners appreciate the benefits and opportunities of SL, such as improving service delivery, developing skills, and building relationships. Matthews (2019) also highlighted that the community partners valued the SL partnerships and believed that the presence of students met a need in the community. However, these studies primarily limit themselves to f2f settings, leaving a gap in the literature concerning online SL engagements.

As the conversation around SL grows, a notable body of work has started to scrutinize the relationship dynamics between academic institutions and Community Partner Organizations (CPOs). Mtawa and Fongwa (2022) and Cohen et al. (2023) offer a critical perspective by exploring issues of power imbalance, unequal partnerships, and the devaluation of community-based knowledge. While these issues are highly relevant to understanding the broader impacts of SL, the existing literature is silent on how these dynamics translate into online SL.

As for how to do online SL, Faulconer (2021) provides a general guide that can be adapted by various academic disciplines for creating effective online SL programs. The guide offers a framework that covers planning, student reflection, and assessment. Another model, by Derreth and Wear (2021), focuses on the Critical Online Service-Learning (COSL) framework which presents a more community-focused perspective, emphasizing action, communication, and social justice. Dumlao (2022) adds a noteworthy contribution through the Collaborative Communication Framework (CCF), which outlines a step-by-step approach to ensure effective communication with community partners in online SL. Although these frameworks brings a systematic approach to the online SL discourse, there is still room for empirical testing to further validate its practical efficacy.

When it comes to implementation challenges and barriers in SL, Lau et al. (2021), Matthews (2019), Mtawa and Fongwa (2022), and Cohen et al. (2023) have identified universal challenges such as mismatched expectations, communication gaps, and logistical difficulties inherent in coordinating schedules between the academic and community partners. Moreover, Dumlao (2022) and Derreth and Wear (2021) have also highlighted some common challenges in online SL, such as technical difficulties and effective communication. The literature also acknowledges the necessity for online SL programs to be participatory and learner-centered, a notion emphasized by online learning researchers like Martin and Borup (2022) and Rajabalee and Santally (2021). Strategies for overcoming online SL challenges include providing needed resources to CPOs as pointed out by Jordaan and Mennega (2022). Finally, Hooijberg & Watkins (2021) and Tian and Noel (2020) discuss the importance of hybrid interactions and community-building for enhancing the authenticity of relationships in online programs. Despite this growing discussion around implementation challenges, there is a need to uncover more on barriers specific to online SL, a critical oversight considering emerging concerns like ‘Zoom fatigue’ discussed by Bailenson (2021).

In conclusion, despite considerable strides in f2f and online aspects of SL, the literature manifests a significant gap concerning the outcomes of online SL engagements on partner communities. This research aims to delve deeply into the specific enablers and barriers influencing these outcomes, thereby offering valuable insights for developing robust online SL programs. As educational paradigms continue to digitalize, it is essential to examine online SL in a nuanced manner to facilitate the design of programs that are not only inclusive but also adaptable across different cultural and geographical landscapes.

Conceptual Framework

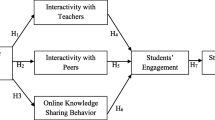

This research adopts the Conceptual Framework of Community Impacts Arising from Service-Learning developed by Lau and Snell (2020), as shown in Figure I below.

According to Lau and Snell (2020), community partner organizations (CPOs) and their beneficiaries are the direct and indirect recipients of service in SL projects. Through literature reviews and validation interviews with CPOs in Hong Kong and developing countries, three major domains of community impact have been identified for CPOs: (1) increasing their capacity level; (2) realizing their goals and values; and (3) attaining new knowledge and insights. For the end-beneficiaries, who are the clients of the CPOs, two major impact domains have been identified: needs fulfillment and enhancement of their quality of life.

In addition to being direct beneficiaries of SL, CPOs may also serve as intermediaries in conveying the community impacts of their end-beneficiaries. This framework offers a comprehensive understanding of the potential outcomes of SL on both CPOs and their target stakeholders. However, the framework might be criticized for oversimplifying intricate community dynamics and the multitude of factors that influence the outcomes of SL. This oversimplification could lead to an inadequate consideration of the full range of potential community outcomes. To address this limitation, this study employed mixed methods to capture the richness and nuance of the experiences and feedback from key community contact persons while simultaneously quantifying the outcomes of online SL projects. Additionally, the framework uses the word “impact,“ which implies long-term effects in development studies literature, when in fact, the more appropriate term is “outcomes” (Belcher & Palenberg, 2018). Therefore, the researchers opted to use the term “outcomes” instead of “impact” throughout this study.

Methods

The study utilized a mixed-methods approach with a convergent design, which involved collecting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data, and merging them to compare or combine the results (Creswell & Clark, 2018). The researchers of this study used this approach to examine the outcomes of online SL engagements on partner communities associated with Ateneo de Manila University (Ateneo) in the Philippines.

Ateneo was chosen as the research setting because of its longstanding commitment to maintaining community-university partnerships through SL initiatives. For instance, Ateneo has a long history of community involvement since the establishment of the Office for Social Concern and Involvement (OSCI) in 1975, which has been tasked with creating a positive impact among marginalized communities through SL across various academic disciplines (Ateneo de Manila University, 2013). Ateneo also pioneered the first SL course in the country, titled “Theory and Practice of Social Development,” or Economics 177 in 1975 (Sescon & Tuaño, 2012), and is committed to using SL to enable students to be persons for and with others (Loyola Schools, Ateneo de Manila University, 2020). In the Ateneo, a comprehensive SL experience is facilitated by integrating SL courses taken by junior college students, such as the National Service Training Program (NSTP) 12 course named Bigkis, managed by formators or student affairs professionals, and the Social Science 13 (SocSc 13) course, titled “The Economy, Society, and Sustainable Development,“ taught mostly by faculty members from the School of Social Sciences in the University.

For the quantitative part of the study, the target research respondents were key contact persons from CPOs who have SL engagements with Ateneo under the collaboration of Bigkis and SocSc 13 courses. For the qualitative part, a minimum of 20 key contact persons from various types of CPOs, such as government, non-government organizations (NGOs), faith-based organizations (FBOs), people’s organizations (POs), etc., were targeted as respondents. Research respondents were specifically those who completed SL engagements spanning the second semester of School Year (SY) 2021–2022 and the first semester of SY 2022–2023.

Data collection in this study comprised online surveys and in-depth online interviews, employing two primary research instruments: the Community Impact Feedback Questionnaire (CIFQ) and Community Organization Interview Questions (COIQ). The CIFQ by Lau and Snell (2021) is a validated tool for assessing perceived SL project outcomes soon after SL project completion. The COIQ, adapted from Barrientos (2010), garnered qualitative feedback on SL outcomes, complementing CIFQ data. Both instruments, available in Filipino following validation by a professional translator, catered to key informants preferring to respond in Filipino.

The study received ethical clearance from the University Research Ethics Office. Participants were briefed on the study, their rights, and procedures. With permission, online interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using the Constant Comparative Method (Glaser & Strauss, 2017). To validate the findings, a series of forums were held with Ateneo’s partner communities and other relevant stakeholders from May to July 2023. These forums aimed to gather feedback and refine the interpretation of the qualitative data. The quantitative data underwent evaluation through descriptive statistics, with the median serving as a key measure for Likert scores. Participant quotes are included in the study; a professional translator translated these from Filipino to English as needed, catering to key informants who preferred to respond in Filipino. The overarching goal of the study was to deepen the understanding of the research problem by merging qualitative and quantitative findings.

Results

Demographic Profile of Research Participants

The quantitative part of the study involved 101 out of the targeted 129 key contact persons who responded to the online survey, representing 46 out of 51 Ateneo CPOs. Of these respondents, 26% (n = 26) were from government organizations, such as government agencies and public schools, while the remaining 74% (n = 75) were from private organizations, such as NGOs, POs, faith-based organizations, cooperatives, and social enterprises. More than half (61%, n = 62) of the CPOs had prior SL partnerships with Ateneo before SY 2021–2022, while the remaining 39% started SL partnerships with Ateneo at the start of SY 2021–2022.

Most online SL projects reported in the survey were direct services (n = 63), such as online training, tutorials, and workshops, followed by research services, such as needs assessments, community/organizational profiling, and feasibility studies (n = 47). Indirect services, such as creating websites, videos, and educational materials (n = 42), and advocacy campaigns were also conducted (n = 42).

Survey respondents identified ICT upgrade and development (n = 53), educational support and assistance (n = 43), leadership and organizational development (n = 38), employment and livelihood development (n = 33), and health and wellness development (n = 28) as the top five needs addressed through online SL projects.

In the qualitative portion of the study, a total of 22 participants were interviewed, consisting of 15 females and 7 males. 12 of the interviewees represented NGO partners, 2 represented government agency partners, 2 represented public school partners, 1 socio-civic partner, 1 private educational institution, 2 FBOs, and 2 represented PO partners.

The two interview groups, each comprising 11 respondents from the January-May 2022 and August-December 2022 batches, highlighted the diverse advantages offered by online Service-Learning (SL) projects. These benefits were distributed across various domains, including educational enrichment through computer literacy programs, academic tutorials, and the production of educational resources. Financial literacy was further fostered through the revision of financial literacy modules. In terms of health and wellbeing, the SL projects facilitated COVID-19 health education and mental health services, demonstrating their applicability in health advocacy. Business development also saw notable advancements through the digitization of business processes, the implementation of operations management systems, and the execution of capacity-building workshops. Lastly, creative pursuits were also supported, reflected in the creation of promotional and literary materials.

Benefits to Partner Communities

The results of the Community Impact Feedback Questionnaire (CIFQ) administered from January to December 2022 are summarized in Table 1. Focusing on the achievement of project goals, Part I of the table shows that online SL projects have effectively furthered the missions of the CPOs. Self-reported scores on a scale from one (lowest impact extent) to 10 (highest impact extent) reveal that these projects not only advanced the mission of the participating organizations (N = 100, Mdn = 8), but also delivered valuable outputs (N = 100, Mdn = 8), improved service quality (N = 100, Mdn = 8), enhanced the organization’s image (N = 99, Mdn = 8), and increased their client reach (N = 99, Mdn = 8). This is further supported by an interview respondent who stated that the projects raised their organization’s ability and capacity:

“The support and help provided by the students are a great addition for us; what we couldn’t handle we were able to manage and we were given assistance with what we found difficult. That’s why I think that’s the significant impact. Our ability is raised, our capacity is increased because of the help and support of the students and formators. (NGO Partner, Female Interview Respondent #7).”

Additionally, the results presented in Part II of Table I show that online SL projects have generally enhanced the resources of partner organizations. Specifically, these projects have somehow generated tangible economic benefits (N = 82, Median = 7). However, they contributed much on human resources (N = 85, Median = 8), valuable return on effort (N = 93, Median = 8), and positive work culture (N = 92, Median = 8). In terms of networking, the survey respondents noted that these projects assisted them in expanding their network (N = 92, Median = 8). One interviewee reported that these projects saved production costs and helped expedite the video-making process necessary for their organization and the communities they serve:

“The three videos they made were very helpful: the AVP about COVID, the one about advocacy on violence against women and children, and the Church and Community Mobilization. If we were to make those ourselves, it would take quite a while to conceptualize and produce so it helped us to speed up the process. We saved on the production cost, hiring consultants, and content creators. (NGO Partner, Male Interview Respondent #2).”

Online SL projects also played a significant role in aiding organizations to acquire knowledge, insights, ideas, and techniques, as indicated in Part III of Table I. Specifically, these projects inspired new ideas and strategies within organizations (N = 99, Mdn = 8), prompted them to reevaluate their work practices (N = 95, Mdn = 8), facilitated the acquisition of new knowledge from the University (N = 99, Mdn = 8), provided opportunities for gaining new experiences (N = 100, Mdn = 8), and improved their work techniques (N = 95, Mdn = 8). An interview respondent expressed that because of the SL projects, their self-confidence grew and that they realized there is a big opportunity to compete and grow in the field of e-commerce:

“I was inspired and my self-confidence grew, knowing that we could keep up with outside markets because before, it seemed like we could only sell to the [local] community. I realized that there is still a big opportunity to compete and grow in the field of e-commerce, especially since everything is mostly online now and there are a lot of orders and this boosted our belief and confidence. (PO Partner, Female Interview Respondent #9).”

Furthermore, the quantitative findings reveal that online SL projects notably improved the well-being of CPOs’ service recipients (N = 96, Mdn = 8) and enhanced their overall well-being (N = 94, Mdn = 8), as shown in Part IV of Table I. The qualitative findings also suggest that online SL cultivated serendipitous connections and relationships. One interviewee shared their experience on how online SL projects helped address the social and emotional needs of their service recipients, especially during the pandemic:

“Surely, the reason why they had the session was to also help our learners cope with the [COVID-19] pandemic. These are the things that became tangible for the kids because they were able to meet other people not just within their homes or classrooms. They were able to interact with other people who could be their friends and who could help them with new learnings such as the different ways of teaching done by the students. (NGO Partner, Female Interview Respondent #4).”

Finally, the survey respondents strongly agree that online SL projects have had a positive impact on their organizations (N = 100, Mdn = 9) and that they intend to continue their SL partnerships with Ateneo (N = 100, Mdn = 9), as shown in Part V of Table I. They also very strongly recommend collaborating on SL projects with Ateneo to other community organizations (N = 100, Mdn = 10). These findings are supported by an interviewee who expressed gratitude for Ateneo’s trust in their community as a venue for learning and exchanging knowledge between students and the community:

“I guess what I can say is that ‘Maalab ang Talab ng Bigkis’ (The Intense Impact of Bigkis) would be an appropriate title for us. From our partner organizations to our community partners, we are very thankful for the trust that Ateneo gave us to make our community a venue for learning and exchanging knowledge among the community and students, in terms of facilitating our community development work. (NGO Partner, Male Interview Respondent #2).”

Enablers of Optimal Online Service-Learning Experience

A CCM analysis of the 22 interview transcripts revealed four key enablers essential for positive online engagement experiences for CPOs. These have been embodied in the acronym CARE, which stands for Collaborative coordination, Active communication, Responsiveness to CPO’s needs, and Engaging online environment, which are discussed below.

Collaborative coordination, signifies careful management of online resources and schedules, demanding close collaboration, flexibility, and proactive problem-solving among campus stakeholders and CPOs. One interviewee, for example, highlighted the importance of choosing an appropriate time and receiving timely reminders:

“It’s good because we are the ones who choose our available time. They did not impose their own schedule on us. They also asked us if we are available at a certain time, what time works for us. That is a good thing because they ask what is suitable for us and this is important for us. Sometimes, we are embarrassed because we would give the time but were the ones who were late or forgot. But they always reminded us [about the meetings] so that we didn’t forget. (NGO Partner, Female Interview Respondent #9).”

The second enabler, Active communication, encapsulates the need for clear, timely dialogue that cultivates trust and understanding, setting the stage to maintain fruitful relationships and expectations among the different stakeholders of online SL. As evidence of this, one interview respondent appreciated Ateneo SL program’s smooth interaction and communication which resolves any uncertainties by ensuring everyone’s expectations are aligned:

“Everything went smoothly. The formators were quick to respond and if there were ever any clarifications needed, we would facilitate discussions with the professors of the classes. While the formators were assigned to each class, it did not necessarily mean that they were experts in those particular courses. So, if they were not clear about something or could not answer our questions, we would typically facilitate and engage with the professors in online discussions. This way, we could align our expectations with our organization and what the students or the class could deliver. (NGO Partner, Female Interview Respondent #12).”

Responsiveness to CPO’s needs, the third enabler, highlights the importance of tailoring online services to meet CPOs’ practical requirements. It promotes needs assessment, targeted training, resource support, and sustainability to enable full and effective CPO engagement in online activities. This includes providing communication and/or food allowances to ensure their full engagement in online activities. One interviewee noted that OSCI goes beyond providing data allowance by offering a small meal allowance to their partners:

“We have exploratory conversations with the formators even before the orientation to establish connections and identify the needs of our community partners. We also consult with our community partners to ensure that scheduling our activities will not disrupt their household or work activities. If there is a need, we provide meal or data allowance from OSCI which is a big help for them. (NGO Partner, Male Interview Respondent #2).”

Finally, the fourth enabler, an Engaging online environment, pertains to a vibrant, interactive, and impactful virtual learning space that stimulates active participation from all stakeholders. This also highlights the importance of active involvement from formators/faculty members to promote engagement and students to organize interactive sessions for CPOs. One interviewee noted the positive impact of online SL engagements with their urban poor youth learners, with emphasis on the enjoyment their learners derived from the fun and playful interactions with the Ateneo students:

“I think they’re [urban poor youth learners] happy. They learned a lot and they also enjoyed the activities conducted by the Ateneo students – you know, their icebreakers and stuff, so they were having fun. For me, that was one of the major positives about their engagement with the Ateneo students. Because you know, they’re so young but their life is already full of stress. So, the playful interactions with the [Ateneo] students, they enjoyed that. (FBO Partner, Female Interview Respondent #14).”

Barriers that Lead to Drawbacks in an Online Service-Learning Engagement

Although the median scores of the CIFQ survey are generally high, there are some items in Table I with extremely low scores of one such as the online SL’s effect on creating economic benefits, expanding the organization’s network, and providing benefits to service recipients to name a few. Despite their outlier status, these low scores warrant closer investigation to discern the underlying reasons for such dissatisfaction. Subsequently, a detailed CCM analysis of the 22 interview transcripts unveiled three principal barriers that impede effective and efficient online SL engagements. These barriers, given the acronym TIP (Time management, Infrastructure, and Participation challenges), while expectedly magnified during online learning contexts, were brought up significantly by the parties interviewed in this study.

Time management challenges emerged as a key deterrent. Delays and difficulties in meeting expectations and deadlines stemmed from bureaucratic delays within the CPO, the crowded workload and demanding schedule of the CPO representatives, and coordination delays on the part of campus stakeholders. The constrained scheduling of engagement opportunities for CPOs and periodic schedule conflicts between CPOs and students amplified these challenges. An interviewee explained that this made communication difficult, and expressed they wanted some online SL engagement opportunities to be rescheduled:

“Of course there were workers who will attend and there would be some challenges. They would ask, ‘How can I go there?,’ something like that. So those were some of the problems that we encountered. Maybe we did not immediately realize that there were already set days [for the online SL engagement] but [turned out to be] in conflict with our immediate concerns. So maybe there were times [when I would think], ‘I hope it’s not on that day; I hope it’s moved to another week.’ (NGO Partner, Female Interview Respondent #7).”

Infrastructure and technical hurdles were the second key barrier. These included fluctuating internet connectivity, limited access to appropriate smart communication tools, inconsistent electrical power supply, and limited knowledge and skills in the use of ICT by the CPO. An interviewee attested to the disruption caused by the internet connection, stating that it posed a significant challenge for their learners:

“The internet connection became more of a challenge for our learners than for the Ateneo students. If I am not mistaken, our students would lose their connection every now and then because there were also learners who wanted to attend… There were also internet connection problems because of their location. (Public School Partner, Female Interview Respondent #1).”

The final hurdle concerns Participation obstacles. From the CPOs’ perspective, this encompasses the lack of physical space to hold hybrid sessions, inconsistent attendance of target participants, and initial apprehension or unease. One interviewee shared their initial hesitancy to participate, feeling shy due to being in the company of Atenistas (the colloquial term for students and alumni from Ateneo). They mentioned that some of their older adult participants expressed a preference to withdraw from participation altogether:

“We were really shy at first because they were Atenistas. The seniors who were with us were really shy in the beginning. They said, ‘Let’s not join them because it’s embarrassing… Let’s not attend and just send the kids [from the community]. It’s embarrassing for the Ateneo students because they’re just going to be annoyed with us.’ (PO Partner, Female Interview Respondent #9).”

The barriers encapsulated by the acronym TIP have indeed resulted in drawbacks in online SL engagement for some CPOs, as evidenced by the lower scores given by some survey respondents for select items in Table I, with scores ranging from one to five. These drawbacks appear in the column for minimum scores. A third acronym, FEAR, captures these drawbacks, specifically focusing on difficulty in providing timely and effective Feedback, disparity in varying levels of Effort displayed by students, erosion of Authentic relationships in prolonged virtual engagements, and concerns about Repetitiveness and nonfulfillment.

The difficulty in providing timely and effective Feedback was one of the prominent challenges faced by CPOs. This challenge stemmed from the difficulty in effectively supervising and supporting students in online settings, often due to the large number of student groups and the hectic schedules of community key contact persons. One interviewee elaborated on this issue:

“It’s difficult to check all the different groups with their different outputs and line of work. They [students] also require different people from our end. So if one person is not available, they will not be able to receive comments from that person since they have a different job to do. Most of the time it goes through me but even I have work that needs to be prioritized. (Government Agency Partner, Male Interview Respondent #3).”

Additionally, the disparity in varying levels of Effort displayed by students highlight the concerns among some CPOs, who worry that they cannot match the high-quality lessons that students deliver to their service recipients:

“Sometimes I realize that your [Ateneo] students are putting a lot of effort in the preparation which is like over preparing in the actual teaching context because the teacher cannot replicate everything that they are doing. We [teachers] cannot always introduce the lesson or session with some fun activity. And we may not be able to do what they are doing about having a gimmick per lesson because it is more important on our part to follow the structure and flow of the lesson. (Public School Partner, Female Interview Respondent #6).”

Another significant drawback involved the erosion of Authentic relationships in prolonged virtual engagements, which led to decreased enthusiasm and participation levels in online SL engagements over time. While some CPOs initially showed eagerness to engage in virtual collaborations and to establish authentic relationships with students, the novelty of online interaction faded as the pandemic extended into its third year, resulting in what many now call ‘Zoom fatigue’:

“One of the biggest challenges would be the limitations of the engagement and the interactions we can foster on an online platform, especially after three years into the pandemic. The problem is that our leaders are experiencing Zoom fatigue. In the beginning, they were excited but by 2022, we noticed a decrease in community members’ participation via Zoom. They were no longer as active as in the past years, probably because they were experiencing technology fatigue or Zoom fatigue. (NGO Partner, Male Interview Respondent #16).”

Finally, there were the Repetitiveness and nonfulfillment concerns. One mentioned that online engagement of students with CPOs seemed repetitive and not maximized for productive endeavors. This, coupled with the limitation of time for other equally important tasks, made CPOs feel unfulfilled in their role, prompting them to question the value of online interactions:

“In the three sessions that were conducted, the participants thought that it was a training or knowledge-sharing session. What happened on the first day of the first session was a whole interview… Then, during the second session, most of the time was consumed before the actual training session. Honestly speaking, the questions were just repeated over and over during the interview. (Government Agency Partner, Female Interview Respondent #11).”

Discussion

Positive Partner Community Outcomes of Online SL Projects

The quantitative data analysis demonstrates that online SL projects resulted in significant and positive partner community outcomes by supporting their missions, enhancing service quality, bolstering their image, and augmenting service delivery capabilities. Additionally, online SL projects yielded some economic benefits, enhanced human resources, and fostered a positive work culture. These projects also improved the well-being of CPOs’ target stakeholders and strengthened their connections and relationships. Survey respondents strongly agreed that online SL projects have had a positive influence on their organizations and expressed a desire to continue their partnerships with Ateneo. They also recommended collaboration with other community organizations.

These findings corroborate the qualitative data, which highlight the enhanced abilities, capacities, and work techniques that CPOs experienced, as well as the valuable learning opportunities for both service recipients and students during online sessions. The key conclusions of the study indicate that SL positively impacts both CPOs and end-beneficiaries in areas such as capacity building, organizational learning, networking, empowerment, social capital, and well-being.

The findings of this study confirm the value and potential of online SL to benefit partner communities. This contrasts some of the prevailing issues in f2f SL, where power dynamics between academic institutions and CPOs have resulted in unequal partnerships, lack of mutual benefit, and devaluation of CPOs’ knowledge (Mtawa & Fongwa, 2022). The results reveal that online SL experiences share similarities with f2f SL in terms of positive community impacts, as shown in previous literature (Kindred, 2020; Matthews, 2019; Towey & Bernstein, 2019; Trager, 2020). The research findings also validate, even in an online SL setting, the conceptual framework of Lau et al. (2021) that divided the immediate impacts of SL into two categories: those that affect the CPOs, the groups providing the service opportunities for the students; and those that affect the end-beneficiaries, who are the recipients of the service from the students.

Facilitating Optimal Engagement in Online SL to Ensure Benefits for Partner Communities (CARE)

This study explored four major enablers, embodied in the acronym CARE, that optimized the online engagement experience for all stakeholders to ensure that online SL engagements benefited not only students and faculty members but the CPOs as well. The enablers include (1) Collaborative coordination; (2) Active communication; (3) Responsiveness to CPO needs; and an (4) Engaging online environment.

For Collaborative coordination, the first enabler, the program allowed CPOs to select their own time slots and sends them regular reminders. This approach respects the CPOs’ preferences and needs while fostering a sense of commitment and accountability among them. This aligns with research emphasizing that online engagement programs should adopt a participatory, learner-centered approach to empower participants and enhance their motivation and engagement (Martin & Borup, 2022; Rajabalee & Santally, 2021). The findings also suggest that online SL programs need the flexibility to adapt to challenges such as technical issues and scheduling conflicts. Campus stakeholders and CPOs must proactively address these issues and communicate effectively to ensure a positive online engagement experience (Dumlao, 2022).

For Active communication, the second enabler, the study found that regular, timely feedback and evaluation are essential for monitoring and improving the quality of online SL. Clear, effective communication in online SL can foster mutual understanding, respect, and social justice through active stakeholder support (Derreth & Wear, 2021).

With regard to the third enabler, Responsiveness to CPO needs, the study highlighted how online SL needs to be aligned with the CPOs’ goals, expectations, and capacities. These were achieved thorough needs assessment, providing adequate training and support, and ensuring the relevance and sustainability of the online service are some ways to achieve this alignment (Derreth & Wear, 2021; Dumlao, 2022).

Finally, for the fourth enabler, having an Engaging online environment highlighted that online SL must utilize various online strategies, such as active and involved formators/faculty, engaging sessions for CPOs, and recorded sessions for asynchronous learning. By creating an energetic and productive online learning atmosphere, online SL can increase the interest and involvement of the stakeholders.

Barriers that lead to Drawbacks in an Online Service-Learning Engagement (TIP and FEAR)

This study identifies barriers that hinder effective online SL, captured by the acronym TIP. These barriers include (1) Time management challenges, stemming from bureaucratic delays, heavy workloads, and coordination issues; (2) Infrastructural and technical problems, such as unreliable internet connectivity, limited access to smart devices, inconsistent power supply, and inadequate ICT skills; and (3) Participation obstacles, like inadequate physical space for hybrid setups, inconsistent attendance, and CPOs’ reservations or concerns.

Subsequently, TIP barriers induced drawbacks in online SL as encapsulated by the acronym FEAR. These drawbacks include (1) difficulty in offering timely and effective Feedback, particularly when supervising large student groups or juggling the busy schedules of CPOs; (2) a disparity in varying levels of Effort by students, raising doubts among CPOs in their ability to replicate the quality of lessons delivered by students; (3) the erosion of Authentic relationships over prolonged virtual engagements, as evidenced by waning enthusiasm and participation levels among CPOs experiencing ‘Zoom fatigue’; and (4) concerns about Repetitiveness and nonfulfillment, which spotlight CPOs’ dissatisfaction and growing doubts about the value of seemingly repetitive online interactions.

These barriers and drawbacks resonate well with the challenges faced with SL even in a f2f setting. In f2f SL, studies have pointed out common limitations like mismatched or unrealistic expectations, power imbalances or unequal relationships, communication gaps, and a lack of sustainability (Lau et al., 2021; Matthews, 2019; Mtawa & Fongwa, 2022). One particular challenge is coordinating schedules between universities and CPOs, an issue exacerbated by differing community workflows and academic timelines (Cohen et al., 2023).

For online SL, Dumlao (2022) emphasizes issues such as technical difficulties, time constraints, cultural differences, and conflicting expectations. Zoom fatigue, a term coined to describe the exhaustion and disconnection stemming from extended video conferencing, is also increasingly prevalent in online learning settings (Bailenson, 2021). To mitigate Zoom fatigue, Bailenson (2021) recommends strategies such as taking frequent breaks, engaging in relaxing activities, and reducing camera use when possible.

To overcome the barriers and drawbacks in online SL, the study’s proponents stress the need to focus intently on the four key enablers—Collaborative coordination, Active communication, Responsiveness to CPO needs, and an Engaging online environment—identified in this study. HEIs can support CPOs by providing financial assistance or needed devices and internet access to those in need or by collaborating with communities to create physical spaces for hybrid sessions (Jordaan & Mennega, 2022). Furthermore, integrating additional opportunities for hybrid interactions and community-building activities into SL programs, such as virtual cultural exchanges and face-to-face social events, can foster authentic relationships, as Hooijberg & Watkins (2021) and Tian and Noel (2020) have previously noted. By implementing these strategies, CPOs can surmount the challenges of online SL, thereby enhancing the programs’ effectiveness and efficiency.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the partner community outcomes of online SL projects in the context of higher education institutions (HEIs) in the Philippines, focusing on the application of the Conceptual Framework of Community Impacts Arising from Service-Learning by Lau and Snell (2020). Using a mixed-method convergent design, the findings confirm that online SL projects yield positive outcomes for partner communities, significantly contributing to their missions, service quality, image, and ability to deliver services. Furthermore, these projects enhance CPOs’ resources by providing economic benefits, human resources, and promoting a positive work culture. Notably, target stakeholders of CPOs also benefit from online SL projects as it boosts their well-being and establishes meaningful connections with others.

The study not only unveils both positive outcomes but also barriers to effective online SL, such as issues of Time management, Infrastructural and technical hurdles, and obstacles to Participation (TIP). These barriers create drawbacks for some CPOs, such as difficulty in providing timely and effective Feedback, the disparity in varying levels of Effort displayed by students, erosion of Authentic relationships in prolonged virtual engagements, and feelings of Repetitiveness and nonfulfillment (FEAR). It is therefore essential to address TIP issues and focus on giving CARE (Collaborative coordination, Active communication, Responsiveness to CPO’s needs, Engaging online environment), that hope to minimize FEAR, ensuring that all stakeholders benefit from online SL engagements.

While the study provides insights into the partner community outcomes of online SL projects, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The study relies on self-reported data and interviews from CPOs within Ateneo which may not be generalizable to the broader population of community stakeholders in the Philippines’ online SL context. Furthermore, the study only covers partner community outcomes of online SL projects; future research should feature longitudinal studies to examine their long-term and sustainable impact. Finally, this study only covers data from SL projects implemented between January and December 2022, so a follow-up study is strongly recommended to examine any trends, changes, or differences in outcome of online SL on partner communities over a longer period.

Despite these limitations, the study has implications for practice and policy in the field of online SL. It provides evidence-based guidance and suggestions for instructors, students, and partner communities involved in online SL projects, highlighting the benefits and drawbacks of online SL and offering strategies for overcoming drawbacks while maximizing benefits. The study also suggests that online SL can be valuable in fostering community development among partner communities, especially in the digital age of the 21st century. Thus, the study calls for more collaboration and communication among online SL stakeholders, as well as more research and evaluation of online SL projects, to ensure optimal quality and effectiveness.

References

Abenir, M. A. D. (2019). The social impact of the service-learning components of the National Service Training Program in the Philippines- The case of the University of Santo Tomas. 7th Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Service-Learning, 1–6. https://www.suss.edu.sg/about-suss/resources/national-service-learning-clearinghouse/the-social-impact-of-the-service-learning-components-of-the-national-service-training-program-in-the-philippines-the-case-of-the-university-of-santo-tomas.

Ateneo de Manila University (2013, September 2). Office for Social Concern and Involvement (OSCI). Ateneo de Manila University. https://2012.ateneo.edu/ls/office-social-concern-and-involvement-osci.

Bailenson, J. N. (2021). Nonverbal overload: A theoretical argument for the causes of zoom fatigue. Technology Mind and Behavior, 2(1), https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000030.

Barrientos, P. (2010). Community service learning and its impact on community agencies: An Assessment study. [Assessment Report]. San Francisco State University, Institute for Civic and Community Engagement, Community Service Learning Program.

Belcher, B., & Palenberg, M. (2018). Outcomes and impacts of development interventions: Toward conceptual clarity. American Journal of Evaluation, 39(4), 478–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214018765698.

Bringle, R. G. (2015). Service-learning essentials: Questions, answers, and lessons learned by Barbara Jacoby. Journal of College Student Development, 56(7), 754–756. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2015.0075.

Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (2009). Innovative practices in Service-Learning and Curricular Engagement. New Directions for Higher Education, 147, 37–46. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ858610.

Cohen, A. L., Walker-DeVose, D., & Andrews, U. (2023). The role of power in experiences of service learning community partners. International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.37333/001c.66274.

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications. Third.

Dapena, A., Castro, P. M., & Ares-Pernas, A. (2022). Moving to e-Service learning in Higher Education. Applied Sciences, 12(11), https://doi.org/10.3390/app12115462.

Dela Cruz, L. J. (2013). In N. Libatique, M. Liberatore, L. Pottier, R. Tuaño, & D. Yu (Eds.), Enhancing University Service-Learning engagements that promote innovations for Inclusive Development: A case study of the Ateneo De Manila Loyola Schools. Loyola Schools, Ateneo de Manila University.

Derreth, R. T., & Wear, M. P. (2021). Critical Online Service-Learning Pedagogy: Justice in Science Education. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 22(1), https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v22i1.2537. 22.1.61.

Driscoll, A., Holland, B., Gelmon, S., & Kerrigan, S. (1996). An Assessment Model for Service-Learning: Comprehensive Case studies of Impact on Faculty, Students, Community, and Institution. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 3, 66–71. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slceslgen/175.

Dumlao, R. J. (2022). Collaborating successfully with community partners and clients in online service-learning classes. Journal of Technical Writing & Communication, 53(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/00472816221088349.

Faulconer, E. (2021). eService-Learning: A decade of Research in Undergraduate Online service–learning. American Journal of Distance Education, 35(2), 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2020.1849941.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206-6.

Hooijberg, R., & Watkins, M. D. (2021, January 4). When Do We Really Need Face-to-Face Interactions? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/01/when-do-we-really-need-face-to-face-interactions.

Jordaan, M., & Mennega, N. (2022). Community partners’ experiences of higher education service-learning in a Community Engagement module. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 14(1), 394–408. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-09-2020-0327.

Kindred, J. (2020). Nonprofit partners’ perceptions of Organizational and Community Impact based on a long-term Academic Service-Learning Partnership. Journal of Community Engagement & Scholarship, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.54656/UQEA3734.

Kung, H. C., & Liu, C. F. (2018). Service-learning in higher education in Southeast Asia. Journal of Economic and Social Thought, 5(3), 273–277. http://www.kspjournals.org/index.php/JEST/article/view/1749.

Lau, K. H., & Snell, R. (2020). Assessing Community Impact after Service-Learning: A Conceptual Framework. 6th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’20), 30-05-2020. https://doi.org/10.4995/HEAd20.2020.10969.

Lau, K. H., & Snell, R. S. (2021). Community Impact Feedback Questionnaire: The user Manual. Office of Service Learning, Lingnan University.

Lau, K. H., Chan, M. Y. L., Yeung, C. L. S., & Snell, R. S. (2021). An exploratory study of the Community impacts of Service-Learning. Metropolitan Universities, 32(2), https://doi.org/10.18060/25482.

Loyola, Schools, & Ateneo de Manila University. (2020). 2020 Undergraduate Bulletin of Information. Office of the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Office of the Registrar, Office of the Vice President for Loyola Schools.

Ma, C. H. K., & Chan, A. (2013). A Hong Kong University first: Establishing service-learning as an academic credit-bearing subject. International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, 6(1), 178–198. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v6i1.3286.

Marcus, V. B., Atan, N. A., Yusof, S. M., & Tahir, L. (2020). A systematic review of e-service learning in higher education. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 14(6), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3991/IJIM.V14I06.13395. Scopus.

Martin, F., & Borup, J. (2022). Online Learner Engagement: Conceptual definitions, Research themes, and supportive practices. Educational Psychologist, 57(3), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2089147.

Matthews, S. (2019). Partnerships and power: Community Partners’ experiences of Service-Learning. Africanus: Journal of Development Studies, 49(1), https://doi.org/10.25159/2663-6522/5641.

Miciano, R. Z. (2006). Piloting a peer literacy program: Implications for teacher education. Asia Pacific Education Review, 7(1), 76–84. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ752329.

Mtawa, N. N., & Fongwa, S. N. (2022). Experiencing service learning partnership: A human development perspective of community members. Education Citizenship and Social Justice, 17(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197920971808.

Rajabalee, Y. B., & Santally, M. I. (2021). Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Education and Information Technologies, 26(3), 2623–2656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10375-1.

Sampa, E. M. (2012). Towards a New Paradigm for Service-Learning as a transformative integrator within and a Bridge between the Academe and Community. The Trinitian Researcher, 4(1), 140–189. http://ejournals.ph/article.php?id=118.

Sandy, M., & Holland, B. A. (2006). Different worlds and Common Ground: Community Partner perspectives on campus-community partnerships. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 13(1), 30–43. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ843845.

Schmidt, M. E. (2021). Embracing e-service learning in the age of COVID and beyond. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000283.

Sescon, J., & Tuaño, P. (2012). Service Learning as a response to Disasters and Social Development: A Philippine experience. Japan Social Innovation Journal, 2(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.12668/jsij.2.64.

Tian, Q., & Noel, T. J. (2020). Service-Learning in Catholic Higher Education and Alternative approaches facing the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Catholic Education, 23(1), 184–196. https://doi.org/10.15365/joce.2302142020.

Towey, W., & Bernstein, R. (2019). Incorporating Community Grant writing as a Service Learning Project in a Nonprofit studies Course: A Case Study. Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership, 9(3), 300. https://doi.org/10.18666/JNEL-2019-V9-I3-8840.

Trager, B. (2020). Community-based internships: How a hybridized high-impact practice affects students, Community partners, and the University. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 26(2), 71–94. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1272300.

Waldner, L. S., Widener, M. C., & McGorry, S. Y. (2012). E-Service learning: The evolution of Service-Learning to engage a growing Online Student Population. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 16(2), Article 2. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ975813.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to the Ateneo Office for Social Concern and Involvement, along with its formators/student affairs professionals, for their invaluable assistance in data collection. We are also deeply grateful to the dedicated research assistants, Ryan Cezar Alcarde, Eala Julienne Nolasco, and Danielle Anne Requilman, for their meticulous attention to detail, diligent work in data collection, and unwavering support throughout the research process.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Ateneo University Research Council (URC) Big Project Grant (control number: URC 03 2022) and the Rizal Library Open Access Journal Publication Grant. In addition, this study received ethical approval from the Ateneo University Research Ethics Office (UREO) (protocol ID: AdMUREC_21_039).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mark Anthony D. Abenir conceptualized the study, collected and analyzed data, interpreted findings, and authored the manuscript. Leslie V. Advincula-Lopez and Lara Katrina T. Mendoza contributed to data interpretation, enhancing the manuscript, and provided critical feedback on the intellectual content. Eugene G. Panlilio assisted in shaping the study design, coordinating with partner communities, and collecting data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests, financial or otherwise, related to the current work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abenir, M.A.D., Advincula-Lopez, L.V., Mendoza, L.K. et al. CARE-full Online Service-Learning in the Digital Age: Overcoming TIP and FEAR to Maximize Community Partner Outcomes in the Philippines. Applied Research Quality Life (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10245-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10245-1