Abstract

There is extensive literature on the relationship between having children and life satisfaction. Although parenthood can provide meaningfulness in life, parenting may increase obligations and decrease leisure time, reducing life satisfaction. In the Netherlands, parental leave is a part-time work arrangement that allows parents with young children to reconcile better work and family commitments. Using panel data from the Dutch Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS), we estimated with fixed-effects models the impact of the part-time parental leave scheme in the Netherlands on the life satisfaction of parents with young children. We find that the legal framework of Dutch parental leave offering job-protected leave and fiscal benefits are conducive to parents’ life satisfaction. Our findings hold using different model specifications. Additionally, we did not find evidence for existing reverse causality and that shorter and more elaborate parental leave schemes are more beneficial for life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Does having children increase our life satisfaction? While many parents would not openly admit that having children does not bring happiness, the reality is more nuanced. While some parents derive joy and a sense of meaningfulness from raising children, the experience of parenting also includes negative emotions such as frustration, worry, and boredom (Senior, 2014). The prevailing belief that children inherently bring happiness may be a focusing illusion, leading us to focus on the positive aspects, such as cute and happy moments, while overlooking potential well-being costs (Powdthavee, 2009).

Research by Hansen (2012) and Pollmann-Schult (2014) indicates that parenting does entail some well-being costs. These costs encompass psychological effects like increased risk of depression (Evenson & Simon, 2005), impacts on marital relationships such as declining satisfaction (Twenge et al., 2003) and increased marital conflict (Shapiro et al., 2000), financial burdens (Stanca, 2012), and role conflicts between work and family domains (Tausig & Fenwick, 2001). Becoming a parent can lead to increased time constraints and family obligations, which can result in a reduction of life satisfaction. Hochschild (1997) describes this phenomenon as a growing ‘time bind,‘ where individuals perceive an imbalance between their work and family responsibilities. Those experiencing a ‘time bind’ feel that both work and family demand significant time, but they struggle to control and balance these demands, ultimately leading to a decrease in their subjective well-being.

Perhaps not surprisingly, studies have found ambiguous evidence regarding the relationship between having children and subjective well-being. A meta-analysis by Luhmann et al. (2012) even indicates a slight negative association between childbirth and parents’ life satisfaction, which seems to be primarily driven by decreased relationship quality. In this regard, Gilbert (2006) shows that marital satisfaction decreases immediately after childbirth and only rises again after the child leaves the home. If children contribute to happiness, it predominantly seems to be the case in the longer run in that grandparenthood has been positively associated with subjective well-being (Arpino et al., 2018; Sheppard & Monden, 2019). Indeed, during grandparenthood people can experience the joys and pleasures of children without necessarily bearing the long-term responsibilities associated with raising them.

At the same time, the association between having children and subjective well-being is heterogeneous and can vary depending on factors such as age, marital status, children’s educational level, and income levels. For example, Angeles (2010) finds that marriage moderates the relationship between having children and life satisfaction, where married people are better off. Cetre et al. (2016) conducted a study in which they show that having children is positively correlated with subjective well-being in developed countries and for people who only become parents at a later age and have a higher income. More recently, Chen et al. (2021) obtained that the relationship between having a child and subjective well-being in China depends on the educational achievement of the child.

Apart from individual circumstances, the institutional context and policies in place to support young families can moderate the relationship between having children and subjective well-being. The generosity of family policies such as childcare subsidies and (paid) parental leave can also decrease the well-being differences between parents and non-parents (Glass et al., 2016). In this regard, there have been several studies conducted on the link between parental leave and subjective well-being (Avendano, 2015; Heisig, 2023 for a review of the literature). All of these studies suggest that parental leave has a positive impact on parents’ subjective well-being. Research conducted in England, Australia, the United States, and Switzerland consistently demonstrate that parents who take parental leave report higher levels of subjective well-being compared to those who do not. Furthermore, among mothers, those who take longer parental leave report higher levels of subjective well-being than those who take shorter leaves.

Along these lines, parents in countries with more generous parental leave policies experience higher levels of subjective well-being compared to parents in countries with less generous policies (Pollmann-Schult, 2018). However, as indicated by Maeder (2014) not all parental leave policies are conducive to (long-term) subjective well-being, especially by negatively affecting their labor market participation if they are designed in such a way as to perpetuate gender stereotypes and gender inequalities. For example, policies that do not provide for paid parental leave may discourage women from returning to work after the birth of their child. Conversely, parental leave policies can have positive effects on women’s participation in the labor market if they are designed in such a way as to encourage a better reconciliation of work and family life. Most notably, policies that offer paid and flexible parental leave can make it easier for women to return to work after the birth of their child. Hence, Maeder’s article highlights the importance of designing parental leave policies that encourage a better work-life balance.

Part-Time Parental Leave in the Netherlands

In this article, we focus on the effect of (part-time) parental leave policy in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, the law on maternity leave was amended in 2008 (European Commission, 2023). Prior to this date, mothers were entitled to 16 weeks maternity leave, of which 6 weeks were compulsory after birth. From 2008, the maternity leave was increased to 16 compulsory weeks, plus 10 optional weeks. In 2013, the law was amended again to allow mothers to take up to 6 weeks maternity leave before the birth of their child’s birth. In addition, fathers are also entitled to two days’ paternity leave which can be taken within four weeks of the child’s birth. In the Netherlands, the law on paternity leave was amended in 2009. Prior to this date, fathers were not entitled to paternity leave but could take unpaid parental leave.

After maternity and paternity leave, employees have the possibility to take parental leave (ouderschapsverlof in Dutch). Parental leave is a legal arrangement that is intended to give parents the opportunity to temporarily work less to take care of their children. Each parent is entitled to a parental leave equivalent to 26 times his or her weekly working hours for his or her child up to the age of 8. The child must live at the same address as the parent, and the parent must provide permanent care for the child. Although an employee cannot be fired for taking parental leave, a parent is legally not entitled to continued payment of wages during parental leave. Yet, fiscal incentives exist to encourage parents to take a break and, in some sectors, (depending on collective labor agreements) employers continue to pay wages. Although employees can decide to take a short full-time leave, most parental leaves in the Netherlands are longer part-time leaves, where parents typically reduce their working time by 0.5 to 2 days.

Comparing the Dutch system with other welfare systems in Europe, the Netherlands normally falls into the category of social-democratic regimes (Esping-Anderson, 1990), characterized by strong social protection and wealth redistribution. By flexible, mostly part-time, parental leave, the Netherlands aims to support families and encourage a better work-life balance. At the same time, compared to other West-European countries, Dutch parental leave policies are rather cumbersome (Plantenga & Remery, 2009). In a cross-national comparison of parental leave policies, Wall and Escubedo (2012) highlight that parental leave policies in the Netherlands resemble more those in the United Kingdom and Ireland, two countries characterized by a rather liberal welfare regime (Boll et al., 2014). Indeed, compared to other European countries, Dutch parental leave is relatively short and less well-paid. For example, in Sweden parents are entitled to 16 months of paid parental leave, while in Germany parents are entitled to receive a minimum of 60% of their salary during the initial 14 months of parental leave – see the overview by Wall and Escubedo (2012) for an elaborate comparison. Plantenga and Remery (2009) primarily attribute the limited Dutch parental leave scheme to the Dutch working-time regime, which is characterized by relatively short full-time working hours and a significant number of people working part-time.Footnote 1 Consequently, there has been limited public pressure for the implementation of extended leave policies.Footnote 2

In sum, parenthood involves family responsibilities and time constraints, which in turn can result in more work-family conflict (Tausig and Fenwick, 2001), which in turn can negatively affect the life satisfaction of parents (Amstad et al., 2011; Greenhaus et al., 2003). At the same time, greater family involvement is associated with higher levels of well-being. One way to mitigate the adverse effects of parenting on parents’ life satisfaction could be to offer specific working time arrangements for parents. The Dutch parental leave scheme serves as an example of such an arrangement as it allows parents with a young child to take parental leave by working part-time instead of full-time. Although this leave is often unpaid in the private sector, there are fiscal incentives to encourage parents to take advantage of it. Hence, the parental leave scheme can help parents to better balance their family and work life, potentially leading to improved life satisfaction.

In this article, we examine the relationship between parental leave and life satisfaction in the Netherlands. Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, few studies have addressed the relationship between parental leave schemes and subjective well-being. Second, we do not only gauge whether parents take parental leave, but examine how different parental leave schemes (e.g., paid versus unpaid and short-term versus long-term leave) differentially affect life satisfaction. We explore the existence of adaptation effects by studying how the parental leave program’s length, intensity, and how the payment scheme moderates the effect between parental leave and life satisfaction. Third, we analyzed the relationship between parental leave and life satisfaction in the case of the Netherlands, where we were, as we know, the first ones to study this relationship for this country.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. We focus on the data and methodology in Section 2. Descriptive statistics and an empirical analysis of the relationship between parental leave and life satisfaction are provided in Section 3, while robustness tests are presented in Section 4. Section 5 discusses and concludes.

Data and Methodology

Data

Our research was conducted using data from the Dutch Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS) panel administered by CentERdata (see for details: www.lissdata.nl). The panel is based on a true probability sample of households selected from the population register by Statistics Netherlands.

In the LISS survey, individuals provide information on several aspects of their lives, including their life satisfaction, parental leave, and socio-demographic detailsFootnote 3. Our analysis was based on an unbalanced common sampleFootnote 4 of 16,496 observations and 4,890 individuals who were observed during the period from 2008 to 2019Footnote 5. Please note that to ensure data consistency, we excluded the years 2014 and 2015 from our analysis. The reason for this exclusion is that the life satisfaction question was asked six months after the question on parental leave, potentially introducing a temporal bias in our resultsFootnote 6. We also chose to exclude the years 2020, 2021, and 2022 from our study as they were the years during which the COVID pandemic occurred. This exogenous shock could have potentially biased our estimations.

Variables

Dependent Variable: Life Satisfaction

Our main indicator for subjective well-being is based on the question, “How satisfied are you with the life you lead at the moment?“ The respondents were asked to use a scale from zero to ten, ranging from “not at all satisfied” (0) to “completely satisfied. (10)” The life satisfaction question offers the advantage of prompting the respondent to focus on an overall evaluation of their life rather than on current feelings or specific psychosomatic symptoms and is a more cognitive measure of subjective well-being. Previous studies by Veenhoven (2000) and Frey and Stutzer (2002) have demonstrated that life satisfaction is closely related to several other measures of overall happiness.

Independent Variable: Parental Leave

To analyze the impact of parental leave on subjective well-being, we created a categorical variable reflecting four possible individual situations:

Reference category (0): The individual does not have any children younger than eight years old. (11,614 obs)

Category (1): The individual has young children but has not reduced his or her working hours at the moment (2,856 obs)

Category (2): The individual has young children and has reduced his or her working hours but is not making use of the parental leave scheme. (1,614 obs)

Category (3): The individual has young children and has reduced their working hours through the parental leave scheme. (412 obs)

Please note that in our taxonomy we decided to focus on parents with a child under the age of eight because parents could choose to take their parental leave until their child reached the age of eight. Yet, most young parents in the Netherlands (about 75%, SCP (2006)) take up parental leave when their child is younger than four. Furthermore, we created an additional category that covers individuals who chose to reduce their working hours outside the legal framework of parental leave. This allowed us to observe whether the benefits of the legal parental leave, such as employment protection, access to tax benefits, and advantageous savings accountsFootnote 7, played a role in explaining the life satisfaction of parents.

Control Variables

In our analysis, we incorporated various control variables that could potentially affect the relationship between parental leave and life satisfaction. These variables include age, living environment, health, education level of the respondent, marital status, primary occupation, net monthly income categories in Euros, and year in which the survey was taken. An overview of all the variables utilized in our analyses can be found in Appendix A.

Econometric Model

We analyze the relationship between parental leave and life satisfaction using the following regression specification:

LSit = β0 + β1YoungNoReducWTit + β2YoungWorkLessit + β3YoungPLit + β4Xit + αi + εit

where i (i = 1, 2, ..., n) refers to individuals, t (t = 1, 2, ..., T) stands for years, and LSit is the self-reported life satisfaction of an individual on a scale from zero to ten. β0 is the constant, Y YoungNoReducWTit is individuals who has a child younger than eight and no reduction of working time, YoungWorkLessit, denotes the individuals having a young child and working less outside parental leave scheme, YoungPLit designates the individuals on parental leave, and Xit represents the vector of covariates that may be correlated to both parental leave and life satisfaction such as work hours categories (Booth and Van Ours, 2013) and having a child younger than four years oldFootnote 8.). αi represents individual-specific time-invariant effects, such as personality, and εit is the error term.

We conduct a linear fixed-effects regression to examine the variation in life satisfaction within individuals over time. An advantage of this analysis is that it controls for unobserved time-invariant variables, such as people’s gender, baseline happiness and personality traits, by differencing them away. As we use “having no young child” as the reference category in our baseline model, the estimated coefficient for parental leave can be interpreted as the change in life satisfaction associated with transitioning from not having a child under the age of eight to having a child under the age of eight and being on parental leave.

Please note that the literature on subjective well-being (SWB) it has often been discussed whether a variable like life satisfaction should be treated as cardinal or ordinal. In this regard, Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004) found that the treatment of life satisfaction as ordinal or cardinal in econometric estimations does not significantly impact conclusions, particularly when the scale has many points. As it is easier to interpret coefficients using a general linear regression, we make use of linear fixed effects models. In addition, we utilized ordered fixed-effects logit regressions (Baetschmann et al., 2020) in a sensitivity analysis.

Empirical Results

Descriptive Statistics

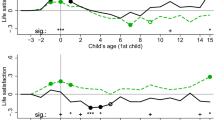

The life satisfaction distributions of individuals with a child under eight and those without in the Netherlands are presented in Fig. 1. The majority of respondents report life satisfaction levels between six and nine, which is consistent with findings in the literature and Dutch life satisfaction averages (Veenhoven et al., 2021). Moreover, the distribution of life satisfaction between these two groups appears to be similar and Table 1 shows then also no differences in life satisfaction between people having a young child and not having a young child. However, individuals who took parental leave demonstrated higher average life satisfaction compared to those who did not. Parents who are not on a parental leave score an average of a 7.6, while parents on a parental leave give their life an average of a 7.8 (see also Fig. 2). The gap between parents with young children that are on parental leave and those is slightly higher for women than for men. At the same time, there are no differences between parents of young children who reduced their working hours outside parental leave and those who did not.

Table 2 presents the socio-demographic characteristics for (1) parents with young children on parental leave, (2) parents with young children that reduced their working hours outside the parental leave scheme and (3) parents with young children not on parental leave. The first column describes the characteristics of individuals who are on parental leave. Individuals on parental leave are predominantly women around the age of 36, with a partner, a high level of education, and children younger than four years old. In total, 270 individuals are observed to take parental leave. Moreover, it can be noted that the average net monthly income of individuals on parental leave is higher than that of individuals with young children who do not take parental leave. In the second column of Table 2, the characteristics of individuals who have young children and choose to reduce their working hours outside the parental leave scheme is presented. These parents exhibit slightly different characteristics compared to those who take parental leave. Specifically, they tend to have a lower level of education, take care of a child older than three years old, and work fewer hours on average. The third column of Table 2 illustrates the distribution of parents who do not reduce their working time. A higher proportion of these parents are single compared to individuals who take parental leave.

Table 3 provides the characteristics those who have taken parental leave within our sample. The majority of individuals in our sample take parental leave for less than two years and continue to work at least two days per week. Only a small proportion of our sample (6%) completely stops working during their parental leave. A majority of individuals are not paid during parental leave, and it is observed that parental leave is more often paid for individuals working in the public sector than for those working in the private sector.

Baseline Estimates

The results of our linear fixed effects estimations are presented in Table 4Footnote 9. We used cluster-robust standard errors at the individual level in our models. Turning to the main results, we found that individuals who transitioned from not having young children to having one and being on parental leave experienced an average increase of 0.2 points in life satisfaction. We observed that this coefficient remained relatively stable even with the addition of various control variables. At the same time, those who transitioned from not having a young child to (1) having one but did not reduce their working hours and to (2) having one and reducing their working hours outside the legal framework of parental leave did not experience a significant change in life satisfaction.

To assess whether the estimated coefficients in the group of individuals on parental leave were significantly different from those of individuals with young children who were not on parental leave, we conducted Wald tests. The Wald tests revealed a significant difference in estimated coefficients between the two groups. This result confirms the parental leave fraemwokr, which includes job-protected leave, the legal obligation for an employer to accept rescheduling a parent’s work arrangement, access to a fiscal benefit, and, in some cases, financial support, enhances parents’ nnn.

Robustness Tests

In the first part, we perform various sensitivity analyses to confirm the robustness of our results. First, we use an alternative indicator for subjective well-being. Next, we re-estimate our specification using an ordered logit fixed effects model and re-run our baseline specification excluding and including specific panel waves. Moreover, we conduct a separate analysis on the sub-sample of individuals having children under four years old. In the second part, we examine the issue of reverse causality and estimate the impact of lagged life satisfaction on the actual decision to take parental leave.

Sensitivity Analyses

First, we replaced the dependent variable, life satisfaction, with a happiness variable, which can be considered an alternative measure of subjective well-being (Veenhoven, 2000). Specifically, respondents were asked: “On the whole, how happy would you say you are? 0 means totally unhappy, while 10 means totally happy”. Estimation results are presented in Table 5 and show that when replacing life satisfaction with the happiness variable, our main conclusion remain unchanged in that we observe a positive and significant association between parental leave and happiness.

Second, we examined whether using an alternative estimator changes our findings. The results using an ordered logit fixed effects model are displayed in Table 6. The first two specifications yield similar results to those found using the linear fixed effects model, where the third specification – including all covariates – the parental leave coefficient becomes insignificant. Further analyses reveal that income plays a mediating role in the relationship between parental leave and subjective well-being, explaining part of the link between parental leave and subjective well-being. Given that this was the only insignificant effect we encountered, we stand with the conclusion that parental leave is conducive to life satisfaction.

Next, we examined whether our results are sensitive to the exclusion and/or inclusion of specific panel waves. In the first column of Table 7, we excluded the year 2008 from our study because the legislation on parental leave has been modified in 2009. Specifically, the legal duration of parental leave was extended. This modification does not change our main result. In the estimation presented in the second column, we included the years 2014 and 2015 to increase the sample size. Initially, we had excluded these years because the questions about parental leave were asked six months before the question about life satisfaction. As a result, there was a significant level of uncertainty regarding whether the respondents were on parental leave or not at the time they answered the life satisfaction question. Finally, in the third column, we add the COVID years to our model to extend our sample size. Once again, we observe that our main result remains unchanged in both cases.

Reverse Causality

Using the linear fixed effects model, we removed omitted fixed variable bias due to individual-specific unobserved heterogeneity related to both parental leave and life satisfaction. This phenomenon means that fixed individual characteristics, such as personality, may influence the choice to take parental leave and life satisfaction simultaneously. However, the linear fixed effects model does not consider possible reverse causality. In other words, it does not address the situation where an individual’s life satisfaction may have influenced the decision to take parental leave. For instance, an individual whose life satisfaction is high may be more open to new experiences (Fredrickson, 2001) and take parental leave to enjoy quality time with his or her firstborn. Conversely, a person going through a depressive episode after the birth of a child may be more disposed to spend more time at work.

To examine whether or not reverse causality is an issue, we examined changes in life satisfaction over time and whether they are associated the decision to take parental leave. Specifically, we estimated a linear fixed effects model in which the dependent variable was the decision to take a parental leave or not, with independent variables life satisfaction in earlier periods and the same covariates as before. If a change life satisfaction predicts the probability of going on parental leave later, we could (potentially) have a reverse causality issue.

In our estimations, we used three different lags for life satisfaction to allow for effects that take shape quickly or more slowly. The relevant parameter estimates of lagged life satisfaction are presented in Table 8. Estimations a, b and c indicated that a positive shock to the life satisfaction of an individual does not increase his or her probability of taking parental leave one, two, or three years later. Rows d to f show that after controlling for covariates, past life satisfaction does not influence the choice to take parental leave. Hence, we concluded that reverse causality from life satisfaction to future choice to take parental leave was not an issue (see also Chen and Van Ours, 2018; Schepen & Burger, 2022).

Heterogeneity Analysis

In this section, we analyze how the life satisfaction of different parental sub-groups is associated with parental leave in the Netherlands. First, we examine how differences in leave schemes may shape the relationship. Second, we explore the influence of socio-demographic characteristics on the estimated impact of parental leave on life satisfaction.

Variation in Parental Leave Scheme

In the Netherlands, people can choose whether they want to use all parental leave days in a short period of time by taking a full-time leave or spread parental leave days over a longer period. Table 9 shows that that in particular shorter leaves and leaves that involve less than three days work seem to be most conducive to life satisfaction. One possible explanation for this finding is that individuals that still work three or four days find it more difficult to combine work and household tasks. This finding is interesting in the light that most parental leave is part-time leave. In addition, Adema et al. (2015) find that across European countries, negative wages and slower career opportunity progression largely follow longer periods of leave from work, e.g. one or two years or more. Consequently, when the parental leave arrangement us spread over an extended period, it may have generate adverse work outcomes for career progression and wages that offset the work-life balance benefits of taking parental leave. However, these interpretations remained speculative, and further research would be needed to better understand the reasons behind these findings.

In our study, we were also able to include information about the remuneration of parental leave from the “work and schooling” survey of the LISS panel data, starting from 2017. Our analysis shows that both paid parental leave (b = 0.24, p < 0.05) and unpaid parental leave (b = 0.14, p < 0.10) reported significantly higher life satisfaction compared to those who chose not to reduce their working hours when they had a child under the age of eight. The Wald test did, however, not show a statistically significant difference between the coefficients for paid and unpaid parental leave. Likewise, we did not find any difference between parents on part-time leave in the public and private sector, despite the former offers more continued payment of wages. We conducted some additional robustness checks using socio-demographic variables such as gender and income. We found that parental leave seems to be more conducive to women and people with higher incomes. At the same time, there were very limited men in our sample and future research is necessary to further examine the gender gap.

Concluding Remarks

In this article, we investigated the relationship between parental leave and life satisfaction. We showed that although having a young child has no significant effect on life satisfaction, life satisfaction is significantly higher among parents with a young child who are on a parental leave scheme. Our findings suggest that a parental leave scheme reduces parents’ perceived ‘time bind’ and increases their subjective well-being. At the same time, a reduction of working time to take care of children outside the Dutch parental leave scheme does not affect life satisfaction, indicating that the legal framework of parental leave offering job-protected leave, the legal obligation for an employer to accept rescheduling a parents’ work arrangement, the possibility to use support services, access to a fiscal benefit, and in some case, financial support is crucial to enhance parents life satisfaction when taking a temporary leave of absence in the form of parental leave to take care of their children. We performed several sensitivity analyses and showed that our findings hold using different estimation strategies and alternative definitions of the dependent variable. Additionally, we did not find evidence of existing reverse causality. The heterogeneity analysis revealed that short, full-time parental leave schemes are significantly more conducive to life satisfaction than extended ones.

Our results may have some implications for public policy. The use of parental leave should be promoted and encouraged by governments. The recent European directive on work-life balance for parents’ careers can, in this regard, help to promote paid parental leave supported by national laws. More generally, Additionally, policymakers should consider implementing family-friendly policies that provide financial safeguards to address work-life imbalances that may arise from being a young parent.

Our study has some limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, we our analysis is restricted to the Netherlands, which may question external validity. The results we have found may not be generalized to other countries. In this regard, cultural specificities and legislation on birth-related leave and childcare systems may moderate the effect of parental leave on life satisfaction. At the same time, paternal leave policies in the Netherlands are rather cumbersome, suggesting that in other European countries with a more elaborate parental scheme the effects on life satisfaction might even be stronger. Second, we dealt with reverse causality by estimating the impact of parental leave on past life satisfaction However, we can only really resolve this issue with a good instrumental variable or natural experiment. An experimental analysis needs to be undertaken to identify the causal impact of parental leave on life satisfaction. Third, a more detailed heterogeneity analysis is needed to find out what works for whom under which circumstances. Preferably, it should be examined how different lifestyles shape the relationship between parental leave and life satisfaction. For instance, family and career-oriented individuals may experience parental leave differently. Such a study would require a larger subsample for people on parental leave. Finally, we assumed that parental leave reduces work-life imbalances and so induces higher life satisfaction, however, we lacked the information needed to undertake a mediation analysis. These relationships should be further examined in future research.

Notes

In the Netherlands, part-time working is a widespread working practice, with around 50% of employees working part-time. This practice is encouraged by the Dutch government, which considers that part-time work can help balance work and private life, particularly for parents who wish to spend more time with their children.

In this regard, research (analyzing the relationship between part-time work and workers’ subjective well-being (e.g., Rudolf, 2014; Shao, 2022; Golden & Wienstuers, 2006; Booth & Van Ours, 2009; Valente & Berry, 2016), suggests that part-time workers have a higher level of subjective well-being than full-time workers, particularly among women and workers with children. Part-time workers may benefit from a better work-life balance, which may contribute to a higher level of subjective well-being.

The panel used in our study was extracted from the LISS database and incorporates data from four panels of the core study: “Personality Questionnaire, LISS Core Study”, “Family and Household Questionnaire, LISS Core Study”, “Health Questionnaire, LISS Core Study”, “Work and Schooling Questionnaire, LISS Core Study”.

The definitions of the relevant variables used in the main models can be found in Tables A1. in Appdiex A.

Our common sample was based on observations of the last column of our baseline estimation.

Note: The presence of observations in 2014 and 2015 may introduce bias in our results, as individuals who responded to the life satisfaction question may no longer be on parental leave during those years. Additionally, it should be noted that the personality questionnaire, which includes the question on life satisfaction, was not conducted in 2016. As a result, we are unable to include data from that specific year in our analysis. More generally, we ensured that the question on life satisfaction was always asked a few months before the questions of interest for our study.

In the Netherlands the legal framework of parental leave offered job-protected leave, the legal obligation for an employer to accept rescheduling a parent’s work arrangement, the possibility to use the LCSS, access to a fiscal benefit, and in some cases, financial support.

Booth and Van Ours (2008) control for child age categories; as our variable young child is a dummy, we could not control for each young child age category; otherwise we would have colinearity issues. So, we only controled for having a one year old child, because parents of a newborn child or newly adopted child are entitled to paternity and maternity leave.

Full estimates can be found in the Appendix Table B1.

References

Adema, W., Clarke, C., & Frey, V. (2015). Paid parental leave: Lessons from OECD countries and selected US states. OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers No. 172.

Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 151.

Angeles, L. (2010). Children and life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 523–538.

Arpino, B., Bordone, V., & Balbo, N. (2018). Grandparenting, education and subjective well-being of older Europeans. European Journal of Ageing, 15, 251–263.

Avendano, M., Berkman, L. F., Brugiavini, A., & Pasini, G. (2015). The long-run effect of maternity leave benefits on mental health: Evidence from European countries. Social Science & Medicine, 132(May 2015), 45–53.

Baetschmann, G., Ballantyne, A., Staub, K. E., & Winkelmann, R. (2020). Feologit: A new command for fitting fixed-effects ordered logit models. The Stata Journal, 20(2), 253–275.

Boll, C., Leppin, J., & Reich, N. (2014). Paternal childcare and parental leave policies: Evidence from industrialized countries. Review of Economics of the Household, 12, 129–158.

Booth, A. L., & Van Ours, J. C. (2008). Job satisfaction and family happiness: The part-time work puzzle. The Economic Journal, 118(526), F77–F99.

Booth, A. L., & Van Ours, J. C. (2009). Hours of work and gender identity: Does part-time work make the family happier? Economica, 76(301), 176–196.

Booth, A. L., & Van Ours, J. C. (2013). Part-time jobs: What women want? Journal of Population Economics, 26(1), 263–283.

Cetre, S., Clark, A. E., & Senik, C. (2016). Happy people have children: Choice and self-selection into parenthood. European Journal of Population, 32(3), 445–473.

Chen, S., & Van Ours, J. C. (2018). Subjective well-being and partnership dynamics: Are same-sex relationships different? Demography, 55(6), 2299–2320.

Chen, Y., Huang, R., Lu, Y., & Zhang, K. (2021). Education fever in China: Children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 927–954.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three Worlds of Welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

European Commission (2023). Parental leave in the Netherlands. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1136&langId=en&intPageId=4811D.

Evenson, R. J., & Simon, R. W. (2005). Clarifying the relationship between parenthood and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(4), 341–358.

Ferrer-i Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 402–435.

Gilbert, D. (2006). Stumbling on happiness. Vintage Books.

Glass, J., Simon, R. W., & Andersson, M. A. (2016). Parenthood and happiness: Effects of work-family reconciliation policies in 22 OECD countries. American Journal of Sociology, 122(3), 886–929.

Golden, L., & Wiens-Tuers, B. (2006). To your happiness? Extra hours of labor supply and worker well-being. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35(2), 382–397.

Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., & Shaw, J. D. (2003). The relation between work–family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 510–531.

Hansen, T. (2012). Parenthood and happiness: A review of folk theories versus empirical evidence. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 29–64.

Heisig, K. (2023). The Long-Term Impact of Paid Parental Leave on Maternal Health and Subjective Well-Being. CESIFO WP 10308 2023.

Hochschild, A. (1997). The time bind. Journal of Labor and Society, 1(2), 21–29.

Luhmann, M., Hofmann, W., Eid, M., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 592.

Maeder, M. (2014). Earnings-related parental leave benefits and subjective well-being of young mothers: Evidence from a German parental leave reform. Working Papers 148, Bavarian Graduate Program in Economics (BGPE).

Plantenga, J., & Remery, C. (2009). Parental leave in the Netherlands. CESifo DICE Report, 7(2), 47–51.

Pollmann-Schult, M. (2014). Parenthood and life satisfaction: Why don’t children make people happy? Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 319–336.

Pollmann-Schult, M. (2018). Single motherhood and life satisfaction in comparative perspective: Do institutional and cultural contexts explain the life satisfaction penalty for single mothers? Journal of Family Issues, 39(7), 2061–2084.

Powdthavee, N. (2009). Think having children will make you happy? The Psychologist, 22(4), 308–310.

Rudolf, R. (2014). Work shorter, be happier? Longitudinal evidence from the korean five-day working policy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1139–1163.

Schepen, A., & Burger, M. J. (2022). Professional financial advice and subjective well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(5), 2967–3004.

Senior, J. (2014). All joy and no fun: The paradox of modern parenthood. Hachette UK.

Shao, Q. (2022). Does less working time improve life satisfaction? Evidence from european Social Survey. Health Economics Review, 12, 50.

Shapiro, A. F., Gottman, J. M., & Carrere, S. (2000). The baby and the marriage: Identifying factors that buffer against decline in marital satisfaction after the first baby arrives. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(1), 59.

Sheppard, P., & Monden, C. (2019). Becoming a first-time grandparent and subjective well‐being: A fixed effects approach. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(4), 1016–1026.

Stanca, L. (2012). Suffer the little children: Measuring the effects of parenthood on well-being worldwide. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81(3), 742–750.

Tausig, M., & Fenwick, R. (2001). Unbinding time: Alternate work schedules and work-life balance. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 22(2), 101–119.

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2003). Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 574–583.

Valente, R. R., & Berry, B. J. L. (2016). Working hours and life satisfaction: A cross-cultural comparison of Latin America and the United States. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 1173–1204.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(1), 1–39.

Veenhoven, R., Burger, M., & Pleeging, E. (2021). Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on happiness in the Netherlands. Mens en Maatschappij, 307–330.

Wall, K., & Escobedo, A. (2012). Parental leave policies, gender equity and family well-being in Europe: A comparative perspective. Family well-being: European perspectives (pp. 103–129). Springer Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Definitions and Description of Variables

Appendix B: Parameter Estimates Baseline model

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dillenseger, L., Burger, M.J. & Munier, F. Part-time Parental Leave and Life Satisfaction: Evidence from the Netherlands. Applied Research Quality Life 18, 3019–3041 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10218-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10218-4