Abstract

While findings have documented the association between adolescent depression and self-injury, few studies have investigated the moderating effect of positive youth development (PYD) qualities on the association. This study examined concurrent and longitudinal predictive effects of depression and PYD qualities on nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidal self-injury (SSI) among Chinese adolescents. The moderating effects of PYD qualities were also studied. Two waves of data with an approximate 6-month interval were collected from five primary and secondary schools in Chengdu, China. A total of 6,948 adolescents aged 10 to 16 (Mage = 12.91, SD = 1.69 at the first wave, 51.17% boys) formed the working sample. Latent moderated structural equation modeling revealed that depression was a positive concurrent and longitudinal predictor of both NSSI and SSI whereas PYD qualities showed adverse concurrent and longitudinal predictive effects. The latent interaction effects were also significant in both cross-sectional and longitudinal models, with PYD qualities mitigating the positive effects of depression on NSSI and SSI. The results suggest that PYD qualities did not only directly reduce the risk of NSSI and SSI among adolescents but also attenuated the influence of depression on self-injury. These findings provide additional evidence for the protective role of PYD qualities in adolescent development and imply that improving PYD qualities may be a promising way to prevent and treat adolescent self-injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidal self-injury (SSI) are both self-destructive that can be differentiated by their intent, methods, chronicity, cognitions, and prevalence, among other factors (Joiner et al., 2012). The former refers to the deliberate behavior causing physical injury to one’s body tissue without any intent to die while the latter involves thoughts, plans, as well as actual attempts to commit suicide (Siu, 2019). Despite the differences, they frequently co-occur. A recent meta-analysis involving 686,672 participants reported that the aggregated lifetime prevalence rates of NSSI and suicidal ideation among children and adolescents were 22.1% and 18.0%, respectively (Lim et al., 2019). NSSI usually peaks during adolescence and will result in significant distress among adolescents and their families. Most importantly, NSSI increases the likelihood of developing suicidal ideation and engaging in later suicidal attempts (Joiner et al., 2012). Suicide has become the fourth leading cause of young people’s death worldwide in 2019 (World Health Organization, 2021). There is a consensus that NSSI and SSI among young people have become major public health concerns that damage their quality of life.

Nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injury behaviors among adolescents are a result of a complex interplay among biological, psychological, psychiatric, and environmental factors. A common theoretical formulation is that predisposing biological (e.g., serotonin imbalances) and personality (e.g., impulsivity) vulnerabilities, together with exposure to negative life events (e.g., interpersonal difficulties or self-injury and suicide of family members or friends) and psychiatric disorders, significantly increase the risk of NSSI and SSI (Bentley et al., 2014; Hawton et al., 2012). For example, self-injury behaviors have long been found to be associated with other psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorder, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, borderline personality disorder, and eating disorder (Bowen et al., 2019; Ghinea et al., 2021; Koutek et al., 2016).

Particularly, depression, among others, has been considered a typical psychiatric antecedent that is prevalent among adolescents (Başgöze et al., 2021; Hawton et al., 2012). From a functional viewpoint, NSSI represents a maladaptive strategy to cope with negative moods and psychological distress, or to express and alleviate pain associated with depression (Angelakis & Gooding, 2021). Unfortunately, the “pain offset relief” produced by the removal or reduction of emotional pain may further reinforce the use of self-damaging as a way of escaping depressed feelings (Angelakis & Gooding, 2021). Pain, hopelessness, and aversive self-perceptions associated with depression may also confer a greater risk of suicidal ideation, which may escalate to suicidal behavior when individuals develop the capability for suicide, i.e., the ability to withstand the physical pain and fear of death involved in suicide (Joiner et al., 2012; Klonsky & May, 2015). In this regard, repeated engagement in NSSI has been considered a salient risk factor for developing fearlessness about pain and death as NSSI is often associated with attenuated perceptions of pain and increased pain tolerance (Joiner et al., 2012).

Despite the strong association between depression and self-injury, not all adolescents suffering depressive symptoms engage in self-destructive behavior. Adolescents’ responses to stress and adversity are also shaped by protective factors, such as personal strengths (e.g., emotional skills and resilience) and external resources (e.g., constructive social bonding and assistance). Embracing this belief, positive youth development (PYD) perspectives shift the focus from youth deficits or psychopathology to their strengths, skills, and assets, which can be nurtured and improved (Shek et al., 2019; Tolan et al., 2016). The PYD perspective is a strength-based approach that sees adolescents as having opportunities to thrive and emphasizes adolescents’ strengths, potentials, and assets as protective factors. Such a perspective is essentially distinct from the traditional deficit perspective that centers on weaknesses and developmental risks in adolescent development (Shek et al., 2019). Although there are different PYD models, a common stand is that PYD qualities, which represent adolescents’ developmental resources derived from inner strengths and positive experiences in interacting with external world, enable them to go through the challenging period more smoothly with better developmental outcomes (Shek et al., 2019).

For example, Catalano et al. (2004) summarized 15 key PYD constructs that had largely contributed to the effectiveness and success of youth prevention programs. These PYD constructs represent a wide range of youth strengths and resources in different domains, and they can be further grouped into four higher-order factors (Shek & Ma, 2010; Zhu & Shek, 2020a). Specifically, the first higher-order factor, cognitive-behavioral competence, consists of the ability of problem-solving and logical, creative, and critical thinking (cognitive competence), the ability to make age-appropriate decision by oneself (self-determination), and to take actions (behavioral competence). The second factor, prosocial attributes, refer to the ability of promoting prosocial values (prosocial norms) and having prosocial behaviors (prosocial engagement). The third one, positive identity, includes qualities of having clear, positive, and healthy perceptions on oneself (positive self-identity) and being optimistic about one’s future (belief in the future). The last one, general PYD qualities, covers eight primary PYD qualities, including the ability to establish and maintain good relationships with helpful adults and peers (bonding), skills to cope with and manage emotions (emotional competence), ability to have effective communication and social interactions (social competence), ability to distinguish between right and wrong and behave morally (moral competence), ability to overcome adversity (resilience), belief that one is able to complete tasks and achieve goals by putting efforts (self-efficacy), purposeful and meaningful feelings (spirituality), and tendency to recognize and appreciate individuals’ desirable behavior (identification with positive behavior).

Considerable evidence has demonstrated that PYD qualities conceived based on the above-mentioned 15 PYD constructs and other frameworks are consistently associated with better developmental outcomes (Shek et al., 2019). For example, rich findings have confirmed the negative association between PYD qualities and adolescent depression (Chi et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Although a handful of prior studies also reported that PYD qualities, such as optimism, resilience, and family support, have protective effects against NSSI among adolescents (Lin et al., 2018; Taliaferro et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020), more studies, especially longitudinal ones, are needed to examine the protective effects of PYD qualities against both NSSI and SSI. In addition, it is even more important to explore whether PYD qualities also serve as a buffer that hinders the pathway from depression to self-injury.

strong PYD qualities allows adolescents to cope with stressors more constructively. For example, left-behind children (i.e., children who stay at home in rural areas while either one or both parents leave to work in urban areas) with higher self-esteem are less likely to develop depression or NSSI after undergoing stressful life events than their counterparts with lower self-esteem (Lan et al., 2019). Recent research also showed that higher levels of cognitive competence, resilience, or overall PYD qualities significantly mitigate the negative association between stress related to COVID-19 and adolescent mental health (Shek, Zhao et al., 2021). Prior evidence collectively suggests that PYD qualities equip adolescents with more intellectual, psychological, and social resources that help them to overcome adversity and avoid resorting to maladaptive coping strategies. In this regard, if depressed adolescents possess more PYD resources, they are more likely to adopt adaptive strategies to cope with the emotional pain, such as practicing effective emotional regulation or seeking help, rather than turning to immediate “pain relief” of self-injuring (Latina et al., 2015).

There are studies exploring the moderating effect of PYD qualities on the influence of depression on self-injury (Jiang et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2020). For example, based on cross-sectional data collected from 1,026 Chinese adolescents, Jiang et al. (2018) found that trait hope significantly mitigate the association between depression and NSSI among female adolescents. Unfortunately, such studies are sparse and even fewer have explored the moderating role of PYD by integrating both NSSI and SSI in one study. In addition, most of existing studies adopt a cross-sectional design with very few longitudinal studies. Furthermore, a methodological limitation of the existing studies should also be noted. Conventional statistical analyses such as multivariate regression for the investigation of moderating effect can only involve a single dependent variable (e.g., NSSI or SSI) in one regression model. Moreover, although psychological constructs like depression, PYD qualities, NSSI, or SSI are conceived as latent variables, prior research employing conventional statistics treats these variables as manifest variables (e.g., calculating a mean total score for a variable) without considering measurement errors. As such, there are views suggesting that the latent moderated structural equation (LMS) technique is superior to other conventional approaches in testing moderating models, as LMS can examine more than one dependent variable in a single model and take into account measurement errors (Feng et al., 2020; Maslowsky et al., 2015).

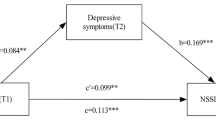

The present study endeavored to advance our understanding of the protective effects of PYD qualities in moderating the relationship between depression and self-injury indexed by NSSI and SSI. First, the main effects of depression and PYD qualities on NSSI and SSI were tested. We expected that while depression would be a positive predictor (Hypotheses 1a and 1b), PYD qualities would serve as a negative predictor (Hypotheses 2a and 2b). Second, we examined the moderating effect of PYD qualities. We expected significant moderating effects of PYD qualities on the predictive effect of depression on NSSI and SSI, where depression would render a weaker predictive power on NSSI and SSI among adolescents with a higher level of PYD qualities (Hypotheses 3a and 3b). The conceptual model is depicted in Fig. 1.

The latent moderated structural equation models. Observed indicators for DP, PYD, NSSI, and SSI, and covariates (age, gender, and baseline NSSI and SSI in the longitudinal model) are not included to avoid unnecessary complexity. Cross-sectional (all variables measured at the same wave) and longitudinal models (DP and PYD at Wave 1 predicted NSSI and SSI at Wave 2) were tested separately

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The data of this study was collected from five primary and secondary schools randomly selected from schools in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province of mainland China. Before data collection, the schools helped obtain written consent from parents of students in these schools (the schools would not reveal the list of parents who did not agree to participate in the study). Then, the students with parental consent were invited to respond to a survey in two waves with a 6-month interval. At the beginning of each wave of data collection, students were well-informed about the principles upheld, including voluntary participation, free withdrawal at any time without any consequences, and anonymity in data analyses and output dissemination. They were also instructed to complete the consent form before responding to survey questions. Students were told that if any of them wished not to participate in the study, they could leave the questionnaire blank.

Specifically, the first wave of data collection took place from 23rd December 2019 to 13th January 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China. The second wave was conducted between 16th June and 8th July 2020, when schools resumed normal operation. The partnered schools, participant children and adolescents, and their parents provided written consent. This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at Sichuan University (K2020025) where the authors’ collaborators were affiliated.

In the first wave, a total of 8,776 students completed the questionnaire with an age range between 7 and 16. Focusing on adolescents, the present study utilized data collected from students aged 10 years or above at the first wave according to the World Health Organization’s definition of the adolescent period (from age 10 to 19). It is believed that primary school students at high grades (i.e., grades 4–6, commonly aged 9 or above) have sufficient intellectual ability to understand self-reporting measures on psychosocial factors and mental health (He & Xiang, 2022). To ensure that student responses are based on their correct understanding of the questions, they were also instructed to ask the research staff administrating the survey if they have any questions about the survey items and to respond to all items based on their honest self-perceptions. Thus, the present participants are able to respond to the survey questions.

A total of 6,992 adolescents were invited to participate in the study with 6,867 and 6,153 of them (response rates = 98.21% and 88.00%) responding to the survey at the two waves, respectively. Among these participants, 6,948 (age range = 10–16 years; Mage = 12.91, SD = 1.69 at Wave 1) had completed data for at least one assessment occasion. As such, the present study utilized these 6,948 adolescents as the final working sample. Among these participants, 3,555 (51.17%) were boys, 3,346 (48.17%) were girls, and 46 (0.66%) did not provide gender information.

Among 6,867 participants at Wave 1, 6,072 of them (age range = 10–16 years; Mage = 12.62, SD = 1.54 at Wave 1) also provided data at Wave 2, suggesting an attrition rate of 11.58% from the first to the second wave. Among 795 students (i.e., dropouts) who were lost in the six-month follow-up, 709 of them were in Grade 9 and did not participate because the 2nd wave of data collection was too close to the high school entrance examination (i.e., 14th − 15th July 2020). As a result, the retained sample was younger than the dropouts. However, the gender composition was not found significantly different between the retained sample and dropouts. The retained sample showed higher levels of PYD qualities but lower levels of depression, NSSI, and SSI at Wave 1 than did dropouts with relatively small effect sizes as indicated by the absolute values of Cohen’s d that ranged between 0.11 and 0.18 (Cohen, 1988). Therefore, attrition was not a major problem. Nevertheless, to reduce potential bias, age and gender were treated as control variables in all formal analyses, and baseline measures were further controlled in longitudinal analyses (see Data Analytical Plan).

Measures

Depression

Adolescents’ depression was measured by the 20-item “Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale” (CES-D). This scale was originally developed by Radloff (1977), including 16 negative symptoms (e.g., “I felt lonely”) and four reverse-coded positive items (e.g., “I enjoyed life”). Using a 4-point scale (“0 = rarely or less than 1 day, 3 = most or all of the time or 5–7 days”), respondents rated their depressive symptoms during the past week. A higher total score across the items indicates a higher level of depressive symptoms. The Chinese version of the CES-D, widely employed in Chinese adolescents studies, has shown a 3-factor structure (“somatic complaints,” “depressed affect,” and “positive affect.”) with good psychometric properties characterized by adequate factor loadings, factorial invariance across gender and over time (Chi et al., 2019; Lau et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2021). In the present study, the scale also demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s αs and McDonald’s ωs above 0.89 across two waves (see Table 1). In the present study, latent depression was indicated by the mean score of the three factors.

Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (NSSI)

Adolescents’ NSSI was measured by the short version of the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (Bjärehed & Lundh, 2008). The respondents were asked how many times (“0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = twice, 3 = three times or more”) they showed the listed nine self-injury acts without an intent to die, including cutting, burning, biting, scratching, self-punching, and so on, during the past six months. This scale has been commonly applied in prior Chinese research and showed adequate psychometric properties (Law & Shek, 2016; Zhu & Shek, 2020b). In the present study, Cronbach’s αs and McDonald’s ωs were higher than 0.87 at both waves (see Table 1), indicating adequate internal consistency of the scale. The latent NSSI was indicated by the nine items.

Suicidal Self-Injury (SSI)

Three items translated and adapted from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023), including “suicidal thoughts”, “suicidal plans”, and “suicidal attempts”, were used to assess adolescents’ SSI in the past six months (“0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = twice, 3 = three times or more”). This scale has been commonly applied to measure overall suicidal ideation and attempts and showed adequate psychometric properties in prior studies (Low, 2021; Zhu & Shek, 2020b). In the present study, the scale also demonstrated good internal consistency as its Cronbach’s αs and McDonald’s ωs were above 0.84 across waves (see Table 1). The latent SSI was indicated by the three items.

PYD Qualities

The “Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale” (CPYDS), which was developed and validated by Shek and Ma (2010), was used to assess students’ self-perceived PYD qualities. On a 6-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree,” 6 = “strongly agree”), the participants evaluated their PYD qualities on 80 items measuring 15 PYD constructs identified by Catalano et al. (2004), such as cognitive competence, resilience, social competence, self-efficacy, and spirituality. Sample items included “I know how to communicate with others” (social competence) and “when I need help, I trust my teachers will help me” (bonding). The 15 PYD constructs were further subsumed under four higher-order factors, including “cognitive and behavioral competence,” “prosocial attributes,” “positive identity,” and “general PYD attributes” as mentioned in the Introduction section. In the present study, the scale showed good internal consistency indicated by Cronbach’s αs and McDonald’s ωs (i.e., above 0.87) of the four higher-order factors (see Table 1). In the analyses, the latent PYD was indicated by the four higher-order factors.

Data Analytical Plan

Descriptive and reliability analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0. Latent moderated structural equation models (LMS, see Fig. 1) were tested using Mplus 8.5 to investigate the main effects of depression and PYD qualities as well as their interaction (i.e., moderating effect of PYD qualities) on NSSI and SSI. All the key factors, including the interaction, were latent variables and measurement errors were considered. We employed the “full information maximum likelihood estimation” (utilizing all available data for each participant) with MLR (i.e., “maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors”) in Mplus to deal with any missing values or non-normally distributed data, respectively (Acock, 2005; Cham et al., 2017). Model fit was assessed by comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI and TLI values above 0.90 together with RMSEA and SRMR lower than 0.08 inform adequate model fit (Kline, 2015).

In the present study, we tested two cross-sectional models using data collected at Wave 1 or Wave 2, respectively, and one longitudinal model with depression and PYD qualities at Wave 1 predicting NSSI and SSI at Wave 2. For each model, model testing included three steps (see Fig. 1). First, the measurement model (i.e., all latent variables were correlated with each other and the latent interaction between DP and PYD was not included) was tested using confirmatory factor analysis. Second, the structural model that only included the main effects but not the interaction was tested (Model 1). Third, Model 2 which further included the interaction effect was compared to respective Model 1. We first tested a model without latent interaction (i.e., Model 1) because Mplus output for LMS does not include model fit indexes such as CIF, TLI, and RMSEA. If Model 1 fitted data well and adding the latent interaction (i.e., Model 2) significantly increased model fit based on the likelihood-ratio test (Klein & Moosbrugger, 2000), Model 2 was preferable (Maslowsky et al., 2015). In all structural models (Model 1 and Model 2), age and gender were included as covariates. In the investigation of longitudinal effects, NSSI and SSI at Wave 1 were also statistically controlled.

Results

Table 1 shows that depressive symptoms were positively correlated with NSSI and SSI concurrently (r = 0.48–0.51, p <0 .001) and longitudinally (r = 0.37 and 0.38, p < 0.001). In addition, all four higher-order PYD measures were negatively associated with depression, NSSI, and SSI at each wave and over time (r ranged between − 0.55 and − 0.15, p < 0.001).

[Table 1 here]

As shown in Table 2, measurement models fitted data adequately without making any modifications (CFI and TLI ≥ 0.91 and MSEA and SRMR ≤ 0.05 for all models). Therefore, structural models can be meaningfully tested. For both cross-sectional and longitudinal models, Model 1 fitted the data adequately (CFI and TLI > 0.91, RMSEA < 0.05, SRMR < 0.06). In addition, according to likelihood-ratio tests, for all analyses, Model 2 was preferred over Model 1 (-2Δloglikelihood ranged between 19.49 and 683.33, Δdf = 2, p < 0.001). In addition, the regression coefficients of the latent interaction on NSSI and SSI were all statistically significant (see Table 3).

Specifically, depression showed positive concurrent predictive effects on both NSSI and SSI (β ranged between 0.41 and 0.45, p < 0.001) whereas PYD qualities showed negative concurrent predictions (β ranged between − 0.12 and − 0.10, p < 0.001, see Table 3) at the two waves. In cross-sectional models, the interaction effect was also significant (β ranged between − 0.27 and − 0.22, p < 0.001), indicating significant moderating effects of PYD qualities in both waves. Figure 2 depicts a plot of the effect of depression on NSSI and SSI at Wave 1 at high (+ 1 SD) or low (-1 SD) PYD qualities with 95% confidence bands. Depression showed weaker associations with NSSI and SSI when adolescents had a relatively high level of PYD qualities.

In the longitudinal model, after the effects of age, gender, and baseline scores were statistically controlled, the main longitudinal effect of depression and PYD qualities were also significant. The latent interaction term also showed significant predictive effects (β = − 0.04, p = 0.03). Depression at Wave 1 showed a weaker effect on NSSI or SSI in six months among adolescents with a higher level of PYD qualities. Based on these findings, the three hypotheses were all supported.

Discussion

The present study investigated the predictive effects of depression on NSSI and SSI among Chinese adolescents during COVID-19. Guided by the PYD models that conceive PYD qualities as a positive contributor to preventing adolescent maladjustment in stressful situations, this study focused on the protective effect of PYD qualities including both the main effect and moderating effect. The findings are consistent with theoretical propositions in general such that depression was a risk factor for NSSI and SSI while PYD qualities was a protective factor. In addition, PYD qualities served as a significant moderator on the effect of depression. Specifically, depression was less likely to result in nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injury among adolescents having higher levels of PYD qualities.

The concurrent and longitudinal positive associations between depression and NSSI and SSI are consistent with previous studies (Hawton et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2020). In general, adolescents having depressive symptoms are likely to suffer from dysfunctional cognitive, affective, and social states such as self-blaming, frustrating feelings, losing optimistic expectations, and lacking positive social connections (Horwitz et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2017). All the suffering may further make adolescents harm themselves or even wish to die as a relief (Bentley et al., 2014). This conjecture is in line with the notion that deliberate self-injury “in essence is more of an effective somehow maladaptive” coping resulting from stress and dysfunctional emotions (Xiao et al., 2020, p. 4). The present findings add further evidence to such a claim by the consistent observation during the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, school lockdowns, forced online classes, and reduced social support during the pandemic may all act as risk factors leading to depression (Shek, 2021). Depressed adolescents are also prone to displaying posttraumatic stress symptoms after experiencing stressful events, such as the COVID-19 outbreak and its related uncertainties and threats (Wang et al., 2022), further increasing the likelihood of committing self-injurious behaviors (Panagioti et al., 2015).

This study also revealed that PYD qualities reduced the risk of both nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injurious behaviors among adolescents. This finding is in line with prior research on the protective effect of internal and external developmental assets such as resilience, emotional competence, or interpersonal bonding (Taliaferro et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020). According to PYD theories (Catalano et al., 2004; Shek et al., 2019), a higher level of PYD qualities (e.g., cognitive skills, emotional skills, positive identity, and resilience) indicates adolescent holistic development, enabling them to go through difficult times more constructively while preventing self-destructive thoughts and behaviors (Law & Shek, 2016). The present findings, together with prior results, collectively suggest that the development of PYD qualities protects adolescents against maladaptive behaviors.

Going beyond the majority of existing research that only highlights the main effect, the present study also showed the protective effect of PYD qualities in terms of mitigating the association between depression and maladaptive behavioral outcomes such as NSSI and SSI. More specifically, depression showed a weaker linkage with both types of self-injury among adolescents of greater PYD qualities. A handful of previous empirical studies have tested similar hypotheses that certain psychological strengths or positive personal attributes, such as resilience and hope, buffer young people’s maladaptive coping against negative or stressful experiences (Jiang et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2020). As such kind of research has yet been scarce, the significant moderating effects of PYD qualities found in this study facilitate our understanding of what factors protect depressed adolescents from NSSI and SSI. A possible mechanism is that PYD qualities allow adolescents to have more constructive responses to their depressed feelings, such as seeking help or performing better emotional management rather than immediate relief (Jiang et al., 2018). The present findings can be regarded as robust as we applied the latent moderated structural equation modeling that rules out the influence of measurement errors (Feng et al., 2020; Maslowsky et al., 2015). Taken together, PYD qualities not only directly lessen the risk of NSSI and SSI but also attenuate the effect of depression on NSSI and SSI.

Based on the linkage between depression and self-injury, depression alleviation through early identification and intervention seems to be a way to reduce NSSI and SSI. However, in adolescents, identification and intervention of depression can be difficult and controversial. In particular, depression may not be easy to detect among adolescents, especially in Asia, due to the culturally inherent stigma (Zhang et al., 2020). Moreover, pharmacological or psychosocial treatment for depression is still surrounded by intense query and controversy (Bevan Jones et al., 2018; Hawton et al., 2012). As such, promoting adolescent PYD qualities could be an alternative that centers on the bright sides of adolescents, thus being more welcomed by students, parents, and schools (Shek et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2021). Many well-known youth programs, especially those implemented in the west, are effective in strengthening multiple PYD qualities and reducing adolescent participants’ dysfunctional outcomes, such as depression and delinquency (Taylor et al., 2017; Zhu & Shek, 2020a). Nevertheless, few is known as to whether such youth programs are as effective in preventing NSSI and SSI. In addition, there is a lack of systematic studies on PYD programs in different Chinese contexts (Shek, Lin et al., 2021; Shek et al., 2022). Hence, there is a call for implementing PYD programs among Chinese adolescents and more studies evaluating the program effectiveness in reducing the risk of NSSI and SSI, particularly under the pandemic (Shek et al., 2023).

The above theoretical and practical implications should be understood by considering several limitations of this study. First, we only collected two waves of data and the time interval (i.e., six months) was not long. Future studies may conduct follow-up studies at more time points so that the predictive effects of the related variables over a longer period can be investigated. Second, the present study collected data from schools in one city. Future studies need to verify and replicate the present findings by involving adolescents in other places. Third, the effect sizes of the longitudinal predictive effects were relatively smaller. While the longitudinal effect is commonly weaker than the cross-sectional one, more efforts are needed to replicate the longitudinal findings. Fourth, COVID-19 pandemic and its related precautionary measures (e.g., school lockdown and sudden shift to online learning) after the first wave of data collection may exert negative influences on students’ mental health status, which has been documented in different studies (Duan et al., 2020; Panchal et al., 2023). Due to the influence of the pandemic as an unpredicted and uncontrolled event, the generalizability of the presenting findings might also be affected. Future studies are needed to replicate and verify the findings.

Despite the above-mentioned limitations, the present findings provide additional evidence for the protective role of PYD qualities in terms of not only directly reducing the risk of self-injury among adolescents but also attenuating the association between depression and self-injury. These findings suggest that improving PYD qualities among adolescents is a promising way to prevent and treat adolescent self-injury.

Data and Material Availability

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author. The predictive effect of depression on self-injury: Positive youth development as a moderator.

References

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1012–1028. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x.

Angelakis, I., & Gooding, P. (2021). Experiential avoidance in non-suicidal self-injury and suicide experiences: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 51, 978–992. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12784.

Başgöze, Z., Wiglesworth, A., Carosella, K. A., Klimes-Dougan, B., & Cullen, K. R. (2021). Depression, non-suicidal self-injury, and suicidality in adolescents: Common and distinct precursors, correlates, and outcomes. Journal of Psychiatry and Brain Science, 6, e210018. https://doi.org/10.20900/jpbs.20210018.

Bentley, K. H., Nock, M. K., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). The four-function model of nonsuicidal self-injury: Key directions for future research. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613514563.

Bevan Jones, R., Thapar, A., Stone, Z., Thapar, A., Jones, I., Smith, D., & Simpson, S. (2018). Psychoeducational interventions in adolescent depression: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 101, 804–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.015.

Bjärehed, J., & Lundh, L. G. (2008). Deliberate self-harm in 14‐year‐old adolescents: How frequent is it, and how is it associated with psychopathology, relationship variables, and styles of emotional regulation? Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 37, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070701778951.

Bowen, R., Rahman, H., Dong, L. Y., Khalaj, S., Baetz, M., Peters, E., & Balbuena, L. (2019). Suicidality in people with obsessive-compulsive symptoms or personality traits. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 747. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00747.

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A. M., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591, 98–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260102.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). Retrieved 10 February 2023 from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm.

Cham, H., Reshetnyak, E., Rosenfeld, B., & Breitbart, W. (2017). Full information maximum likelihood estimation for latent variable interactions with incomplete indicators. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 52, 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2016.1245600.

Chi, X., Liu, X., Guo, T., Wu, M., & Chen, X. (2019). Internet addiction and depression in Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 816. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00816.

Chi, X., Liu, X., Huang, Q., Huang, L., Zhang, P., & Chen, X. (2020). Depressive symptoms among junior high school students in southern China: Prevalence, changes, and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 1191–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.034.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Second ed.). New York: Academic Press.

Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029.

Feng, Q., Song, Q., Zhang, L., Zheng, S., & Pan, J. (2020). Integration of moderation and mediation in a latent variable framework: A comparison of estimation approaches for the second-stage moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2167. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02167.

Ghinea, D., Fuchs, A., Parzer, P., Koenig, J., Resch, F., & Kaess, M. (2021). Psychosocial functioning in adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury: The roles of childhood maltreatment, borderline personality disorder and depression. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 8, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-021-00161-x.

Hawton, K., Saunders, K. E. A., & O’Connor, R. C. (2012). Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet, 379, 2373–2382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5.

He, N., & Xiang, Y. (2022). Child maltreatment and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effect of psychological resilience and loneliness. Children and Youth Services Review, 133, 106335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106335.

Horwitz, A. G., Berona, J., Czyz, E. K., Yeguez, C. E., & King, C. A. (2017). Positive and negative expectations of hopelessness as longitudinal predictors of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior in high-risk adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 47, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12273.

Huang, Y. H., Liu, H. C., Sun, F. J., Tsai, F. J., Huang, K. Y., Chen, T. C., Huang, Y. P., & Liu, S. I. (2017). Relationship between predictors of incident deliberate self-harm and suicide attempts among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60, 612–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.005.

Jiang, Y., Ren, Y., Liang, Q., & You, J. (2018). The moderating role of trait hope in the association between adolescent depressive symptoms and nonsuicidal self-injury. Personality and Individual Differences, 135, 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.010.

Joiner, T. E., Ribeiro, J. D., & Silva, C. (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and their co-occurrence as viewed through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 342–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412454873.

Klein, A., & Moosbrugger, H. (2000). Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika, 65, 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296338.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (Fourth ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2015). The three-step theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8, 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114.

Koutek, J., Kocourkova, J., & Dudova, I. (2016). Suicidal behavior and self-harm in girls with eating disorders. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 787–793. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S103015.

Lan, T., Jia, X., Lin, D., & Liu, X. (2019). Stressful life events, depression, and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese left-behind children: Moderating effects of self-esteem. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00244.

Latina, D., Giannotta, F., & Rabaglietti, E. (2015). Do friends’ co-rumination and communication with parents prevent depressed adolescents from self-harm? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 41, 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.10.001.

Lau, J. T. F., Walden, D. L., Wu, A. M. S., Cheng, K. M., Lau, M. C. M., & Mo, P. K. H. (2018). Bidirectional predictions between internet addiction and probable depression among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7, 633–648. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.87.

Law, B. M. F., & Shek, D. T. L. (2016). A 6-year longitudinal study of self-harm and suicidal behaviors among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 29, S38–S48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2015.10.007.

Lim, K. S., Wong, C. H., McIntyre, R. S., Wang, J., Zhang, Z., Tran, B. X., Tan, W., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2019). Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 4581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224581.

Lin, M. P., You, J., Wu, Y. W., & Jiang, Y. (2018). Depression mediates the relationship between distress tolerance and nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents: One‐year follow‐up. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48, 589–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12382.

Low, Y. T. A. (2021). Family conflicts, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation of Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16, 2457–2473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09925-7.

Maslowsky, J., Jager, J., & Hemken, D. (2015). Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414552301.

Panagioti, M., Gooding, P. A., Triantafyllou, K., & Tarrier, N. (2015). Suicidality and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50, 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0978-x.

Panchal, U., Salazar de Pablo, G., Franco, M., Moreno, C., Parellada, M., Arango, C., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 1151–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306.

Shek, D. T. L. (2021). COVID-19 and quality of life: Twelve reflections. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09898-z.

Shek, D. T. L., & Ma, C. M. S. (2010). Dimensionality of the Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale: Confirmatory factor analyses. Social Indicators Research, 98, 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9515-9.

Shek, D. T. L., Dou, D., Zhu, X., & Chai, W. (2019). Positive youth development: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health Medicine and Therapeutics, 10, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S179946.

Shek, D. T. L., Lin, L., Ma, C. M. S., Yu, L., Leung, J. T. Y., Wu, F. K. Y., Leung, H., & Dou, D. (2021a). Perceptions of adolescents, teachers and parents of life skills education and life skills in high school students in Hong Kong. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16, 1847–1860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09848-9.

Shek, D. T. L., Zhao, L., Dou, D., Zhu, X., & Xiao, C. (2021b). The impact of positive youth development attributes on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Chinese adolescents under COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68, 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021b.01.011.

Shek, D. T. L., Peng, H., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Editorial: Children and adolescent quality of life under socialism with Chinese characteristics. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17, 2447–2453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09999-3.

Shek, D. T. L., Leung, J. T. Y., & Tan, L. (2023). Social policies and theories on quality of life under COVID-19: In search of the missing links. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 18, 1149–1165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10147-2.

Siu, A. M. H. (2019). Self-harm and suicide among children and adolescents in Hong Kong: A review of prevalence, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64, S59–S64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.004.

Taliaferro, L. A., Jang, S. T., Westers, N. J., Muehlenkamp, J. J., Whitlock, J. L., & McMorris, B. J. (2020). Associations between connections to parents and friends and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: The mediating role of developmental assets. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25, 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104519868.

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta‐analysis of follow‐up effects. Child Development, 88, 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864.

Tolan, P., Ross, K., Arkin, N., Godine, N., & Clark, E. (2016). Toward an integrated approach to positive development: Implications for intervention. Applied Developmental Science, 20, 214–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1146080.

Wang, Y., Luo, B., Hong, B., Yang, M., Zhao, L., & Jia, P. (2022). The relationship between family functioning and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: A structural equation modeling analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 309, 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.124.

World Health Organization. (2021). Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Xiao, Y., He, L., Chen, Y., Wang, Y., Chang, W., & Yu, Z. (2020). Depression and deliberate self-harm among Chinese left-behind adolescents: A dual role of resilience. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 48, 101883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101883.

Zhang, Z., Sun, K., Jatchavala, C., Koh, J., Chia, Y., Bose, J., Li, Z., Tan, W., Wang, S., Chu, W., Wang, J., Tran, B., & Ho, R. (2020). Overview of stigma against psychiatric illnesses and advancements of anti-stigma activities in six asian societies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010280.

Zhou, Z., Shek, D. T., Zhu, X., & Dou, D. (2020). Positive youth development and adolescent depression: A longitudinal study based on Mainland Chinese high school students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 4457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124457.

Zhu, X., & Shek, D. T. L. (2020a). Impact of a positive youth development program on junior high school students in mainland China: A pioneer study. Children and Youth Services Review, 114, 105022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105022.

Zhu, X., & Shek, D. T. L. (2020b). The influence of adolescent problem behaviors on life satisfaction: Parent–child subsystem qualities as mediators. Child Indicators Research, 13, 1767–1789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09719-7.

Zhu, X., Shek, D. T. L., & Dou, D. (2021). Factor structure of the Chinese CES-D and invariance analyses across gender and over time among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 639–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.122.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating schools and adolescent participants as well as their parents, who gave great support to this study.

Funding

This project and this paper are financially supported by Wofoo Foundation and the Research Matching Fund of the Research Grants Committee (R.54.CC.83Y7).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. DS: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was received from the institutional review board (IRB) at Sichuan University (K2020025) where the authors’ collaborators were affiliated.

Informed Consent

Informed consent were obtained from all participants and their parents.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, X., Shek, D. The Predictive Effect of Depression on Self-Injury: Positive Youth Development as a Moderator. Applied Research Quality Life 18, 2877–2894 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10211-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10211-x