Abstract

The broad conceptualisation of wellbeing has allowed researchers to establish subjective wellbeing as a valid indicator of social development. However, changing social patterns, norms, and values suggest changes in how social determinants may predict subjective wellbeing. The current analysis tests a serial mediation hypothesis in which social participation and social resources mediate the effect of general trust on subjective wellbeing.

Data from 8725 participants were pooled from the German part of the European Social Survey (ESS) Wave 10. Structural models were estimated to access the path from general trust to subjective wellbeing (SWB). Three separate mediation analyses were performed to test (1) the indirect effect of general trust on SWB through social participation, (2) through social resources and (3) through social participation and social resources. A full-mediation model reveals the direct and indirect paths predicting SWB through general trust, social participation, and social resources. Gender, age, education, and household size were included as control variables.

The full-mediation model suggests significant results for direct paths from general trust to social participation, social resources, and SWB. Direct paths from social participation to social resources and SWB were also significant. However, the path from social resources to SWB became non-significant.

Results highlight general trust as a critical predictor of SWB. The finding that social participation is significant while social resources are not significant in a mediation model suggests that social participation directly affects wellbeing, independent of the effect of social resources. This highlights the importance of social participation in promoting wellbeing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The empirical exploration of group and individual wellbeing continues to dominate research on health and general life enquiries. Wellbeing as a measure of life outcomes is inferred from physical and mental health, positive mood states, feelings of personal control, and meaningful life (Diener, 2021). This broad conceptualisation of wellbeing has allowed researchers to establish the individual assessment of wellbeing as a valid indicator of social development and an essential aspect of public health (Diener et al., 2009; Sharpe, 1999; Søvold et al., 2021). However, the subjectiveness of wellbeing has made it susceptible to socioeconomic, cultural, and social connectedness variances, such as trust, social participation and social resources. Changes to the individual social or physical environment or socioeconomic status often correspond to the revaluation of significant predictors of a good life (Brereton et al., 2011). While researchers continue to explore the core value that predicts better wellbeing, the continual parallel changes to social dynamics project constant and drastic shifts in the predictive strength of various determinants of wellbeing (Dixon & McKeown, 2021).

Research on wellbeing often emphasises the social determinants of health (Dyar et al., 2022). The central role of social determinants of health in understanding wellbeing is exemplified by various theoretical models which capture the social environment as playing a crucial role in wellbeing (Dyar et al., 2022; Ward & Meyer, 2009). One of the major social determinants of wellbeing which has been emphasised by wellbeing researchers is social relationships or connectedness to people (Diener, 2021; Ferrari, 2022). The role of social relationships in human wellbeing is important because people are social beings who feel a psychological need to belong (Escalera-Reyes, 2020). The importance of the social environment is captured in various public health models. For example, the Dahlgren-Whitehead rainbow is a model of health that emphasises a supportive environment for health and wellbeing (Dahlgren et al., 2006). It indicates among other components, social and community networks, including family and wider social circles, contribute to people’s wellbeing. This theory thus suggests that the connection or interaction with other people helps build the social capital that could be instrumental in promoting wellbeing.

Research on social determinants of health often investigates some determinants in isolation without taking cognisance of the multiple and interwoven nature of the contributory factors to this aspect of human health (Dyar et al., 2022; Ward & Meyer, 2009). Researching the interconnectedness of the determinants of wellbeing has thus become a revered approach by health researchers (Dyar et al., 2022; Rice & Sara, 2019; Ward & Meyer, 2009). While still focusing on social connectedness as a determinant of wellbeing, this study aims to explore how different aspects of social connectedness relate to impact wellbeing.

An aspect of social relationships or connectedness to people is trust. The need to belong also espouses feeling secure with others and having their care and affection (Escalera-Reyes, 2020). General trust has been identified as a predictor of subjective wellbeing (Helliwell et al., 2016; Helliwell & Wang, 2010; Mironova, 2015). The perception that people are largely reliable and would act in one’s interest has been described as a foundation that binds individuals, groups and society together (Kwon, 2019). As societies thrive on interdependence, trust becomes an essential human attribute in social relationships and, in turn, wellbeing. For example, in a sample of Sub-Saharan African migrants in Germany, Adedeji et al. (2021a, b) found that trust and sociability accounted for 24% and 19% variance in quality of life for male and female participants, respectively. This emphasises that trust in a social relationship engenders feelings of belongingness and a psychological sense of community that promote better life outcomes. As such, the presence or absence of trust usually predicts the strength of social relationships and participation. In social interactions, trust stimulates the feeling of security and optimism and encourages cooperative behaviours (Bottoni, 2018; Escalera-Reyes, 2020). Consequently, social distrust may facilitate social disintegration (Olonisakin & Idemudia, 2023) and a decline in subjective wellbeing (Olonisakin & Idemudia, 2022).

The link between general trust and subjective wellbeing is captured in the Social Quality Theory which proposes that trust is an essential element of social relationships and is crucial to the social quality of individuals and communities (Lin & Herrmann, 2015; Ward & Meyer, 2009). Social quality is construed as the extent to which individuals can be fully engaged in the economic, social, and cultural life of their environment in a way that improves their wellbeing and individual potential. In sum, the theory portrays human living as encompassing interdependence in inter-personal and person-social system interactions and trust as essential to these interactions. Interpersonal trust develops from a confidence to rely on other individuals whereas institutional trust arises from the confidence to rely on the social systems. The mistrust or the inability to trust leads to hypervigilance, anxiety, and insecurity in social relationships. As such being able to trust others and the social systems help to alleviate hypervigilance, anxiety, and feelings of insecurity and in turn promote wellbeing (Ward & Meyer, 2009). Building on theoretical and empirical findings, it may be argued that higher general trust enables social participation and improves individual subjective evaluation of life.

Another aspect of social connectedness is social participation. Social participation captures the extent of individuals’ engagement or immersion in activities that promote interaction with other members of a society (Ang, 2018). More holistically, social participation is “a person’s involvement in activities that provide interaction with others in society or the community” (Levasseur et al., 2010). The role of social participation in promoting subjective wellbeing has been documented by various studies (Diener, 2021; Ferrari, 2022; Schmiedeberg and Schröder, 2017). However, recent research has suggested drastic changes in patterns in social participation. These changes are grossly attributed to changing world demography (Hamel, 2022; Liu et al., 2020), technological advancement and social media (Kim & Ellison, 2022; Mohammed & Ferraris, 2021; Norman et al., 2015), changing social values (Ravulo et al., 2020), and the COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying restrictions that limited physical and social interactions (Khan et al., 2022). Parallel to these changes, new findings have continued highlighting the importance of social participation as a mechanism for belongingness and a determinant of subjective wellbeing (Escalera-Reyes, 2020). These findings argue that the relationships shared with others contribute significantly to individual subjective wellbeing. For example, living in a socially hostile environment has been shown to substantially reduce individuals’ subjective wellbeing (Diener, 2021).

With social participation, people build social networks and ties that provide social support and enhance their wellbeing (Adedeji, Silva et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). As such, social participation contributes to the social connectedness in individual’ subjective wellbeing. However, while social participation can promote wellbeing, we postulate that it is predicated on people’s trust in their community, environment, and people. We put forward that social participation is the pathway through which trust enhances wellbeing. Trust makes people willing to participate in groups and activities and expect positive outcomes. Respectively, with such participation and the built relationships come positive outcomes, for example, positive mood states, social support and social validation that can contribute to wellbeing (Diener, 2021; Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, trust appraisal would likely feature in an individual’s decision for social participation in their environment or community. This point of view is supported by research that has linked trust to increased receptivity towards shared activities with others (Ahamed & Noboa, 2022; Sabetzadeh & Chen, 2023; Wu et al., 2009).

Furthermore, a third aspect of social connectedness is social resources. Social resources focus on the availability of social networks and support in the context of the sociocultural environment (Campbell et al., 1986; Murray Nettles et al., 2000). It refers to the social ties and social support networks that are built or accumulated from social participation in the community. Social resources could take the forms of friendship, information sharing, and emotional support available for socialising or coping with adverse experiences. The availability of social resources is one of the most important contributors to wellbeing that has been identified in the pertinent literature (Diener, 2021).

Building on social participation arising from trust, we propose that social resources are accumulated through social participation. Through social participation, people create social networks that can provide or share resources that promote wellbeing. It is therefore assumed that the relationship between trust and wellbeing occurs through a pathway in which trust promotes social participation, impacts the social resources available to an individual, and culminates wellbeing. Based on the assumed relationships, do higher levels of general trust associate with increased social participation and social resources, and in turn, higher subjective wellbeing?

To answer this question, the present study aims to test a serial mediation hypothesis in which social participation and social resources mediate the relationship between general trust and subjective wellbeing. To achieve this objective, the following hypotheses will be tested:

H1. General trust will positively predict subjective wellbeing.

H2. Social participation will mediate the relationship between general trust and subjective wellbeing.

H3. Social resources will mediate the relationship between general trust and subjective wellbeing.

H4. Social participation and social resources will serially mediate the relationship between general trust and subjective wellbeing.

Method

Study Design

The current analysis examined the structural path between general trust, social participation, social resources and subjective wellbeing using a representative sample of the German population. The study used cross-national data from the tenth wave of the European Social Survey (ESS). The ESS is an academically driven social survey to collect data on European populations’ attitudes, beliefs, and behavioural patterns (ESS, 2023). Data are collected from participating countries as a biennial survey (Dorer, 2012) and are available on the ESS data website (https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/).

Data were pooled from the German part of the ESS conducted in 2020 by the GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. Population sampling was done using a two-stage, disproportionately stratified random selection for persons living in private households in Germany aged 15 and over, irrespective of their residence status. Social constructs relating to social participation, general trust, life outcomes (subjective health, life satisfaction, happiness, and social resources), socioeconomic status (SES), and demographic characteristics were retrieved from the dataset. Overall, data from 8725 participants were included in the analysis.

Measures

Predictor Variables

General trust. General trust among the participants was assessed to examine interpersonal trust (Edward L. et al., 2000). Trust was captured using a 3-item scale (Arbor, 1971). The three items have been tested and established as valid measures of trust in the social context (Hetherington, 1998; Yamagishi, 1986). Each item was rated on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 – lowest trust to 10 – highest trust. An example of the item is “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” with responses ranging from 0 = can’t be too careful to 10 = most people can be trusted. Higher scores suggest stronger trust. The trust scale presented good reliability for the current sample with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.77.

Mediating Variables

Social Participation. The concept of social participation describes the extent and nature of individuals’ involvement in social activities and the level of their involvement in society (Piškur et al., 2014a). Data on social participation was collected using two items. The first item asked questions on “how often participants socially meet with friends, relatives, or colleagues” using a 7-point scale: 1 = never, 2 = less than once a month, 3 = once a month, 4 = several times a month, 5 = once a week, 6 = several times a week, and 7 = every day. The second item assesses how often participants “take part in social activities compared to others of the same age”, with responses ranging from 1 = much less than most, 2 = less than most, 3 = about the same, and 4 = more than most, to 5 = much more than most” (Guillen et al., 2011).

Social resources. Social resources focus on the availability of intimate networks and support in the context of the sociocultural environment (Campbell et al., 1986; Murray Nettles et al., 2000). The level of available social resources was measured with a single item: “How many people do you have with whom you can discuss intimate and personal matters” with responses ranging from 0 = none, 1 = one person, 2 = two people, 3 = three people, and 4 = four to six people, to 5 = seven to nine people, 6 = ten or more people. This single-item measure derived from Weiss’s “emotional isolation” (Weiss, 1973) has been shown to measure individual social resources in European samples (Pinillos-Franco & Kawachi, 2018; Swader, 2019).

Outcome Variables

Subjective Wellbeing (SWB). SWB was conceptualised as participants’ life satisfaction, happiness, and subjective health. Life satisfaction examined subjective assessments of positive affect as a measure of subjective wellbeing (Neugarten et al., 1961; Pavot & Diener, 2008). Life satisfaction was measured as “how satisfied are you with life as a whole” using a scale from 0 = not at all satisfied to 10 = extremely satisfied. The item relating to happiness is conceived as the degree to which a person generally feels good about themself and how favourable they are compared with various measures of success (Veenhoven, 1991). Happiness was measured using a similar scale. Participants were asked to rate “how happy are you” from 0 to 10, with 0 = extremely unhappy to 10 = extremely happy. Subjective health is based on existing studies that have adopted a similar approach to self-evaluation of one’s health (Cislaghi & Cislaghi, 2019; Haddock et al., 2006). Subjective health was captured using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = very good health to 5 = very bad health. This item was recorded to match the direction of other items capturing participants’ life outcomes, i.e., 5 = very good health and 1 = very bad health. A latent variable, “subjective wellbeing,” is derived as observed life satisfaction, happiness, and subjective health. The reliability test of the latent variable life outcome returns an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.65.

Covariates

Data on participants’ demographic and educational attainments were included as covariates. Participants’ age was measured in years and treated as a continuous variable; participants’ gender was categorised as male or female. Household size was measured as the number of people regularly living as household members and was treated as a continuous variable. Participants’ education attainment was reported using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCE). The seven categories ranged from 1 = less than lower secondary to 7 = higher tertiary education, greater or equal to a master’s degree.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of sample demographic characteristics and education were reported as means (M), standard deviations (SD), frequencies (n) and percentages (%).

The structural model was estimated with data from 8725 participants from Germany in the tenth wave of the ESS (collected in the year 2021). The estimation method was the maximum likelihood, and model fit was assessed based on the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardised root mean squared residual (SRMR). A model was considered to have a good fit when the CFI ≥ 0.95, the RMSEA ≤ 0.06 (p > .05) and the SRMR ≤ 0.08. An acceptable fit was defined by a CFI ≥ 0.90 and an RMSEA ≤ 0.10 (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

First, three separate mediation analyses were performed. The first model tested the indirect effect of general trust on SWB through social participation. The second model tested the indirect effect of general trust on SWB through social resources. The third mediation model assessed general trust’s indirect effect on SWB sequentially through social participation and social resources. Finally, a full mediation model indicated the direct and indirect paths in predicting SWB through general trust, social participation, and social resources with standardised estimates. Gender, age, education, and household size were included in the model as control variables. The Structural Equation Modeling was performed with an Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS Development Corporation, Meadville, PA).

Results

As shown in Table 1 below, the average age of participants was 50.3 years (SD = 19.1). About half of the participants were female. The average household size was computed as 2.5 (SD = 1.2). Data on education suggest only about one per cent reported less than lower secondary education. In comparison, roughly 18 per cent had completed at least a master’s degree. Close to one-third of the participant had educational attainment categorised as lower tier upper secondary.

Measurement Model

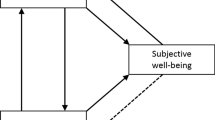

The measurement model is displayed in Fig. 1. The model consists of three latent constructs (social participation, general trust, and subjective wellbeing) and eight manifest variables. An assessment of the fit indices showed that the measurement model achieved a satisfactory fit: χ2 (17) = 368, p < .001; SRMR = 0.03; CFI = 0.98 and RMSEA = 0.05 [90% CI = (0.04, 0.05)]. All the indicators loaded significantly at p < .001 on their respective latent constructs. In addition, the latent constructs of general trust, social participation, and subjective wellbeing were significantly inter-correlated.

Validity and Reliability of Measures

Table 2 below indicates composite reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity. The composite reliabilities for the measures of general trust (0.77), social participation (0.61), and SWB (0.68) were greater than the cut-off of 0.60 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). An examination of the indices of validity shows that all the measures achieved discriminant validity, given that the square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) (0.66 to 0.73) were above the inter-construct correlations (0.25 to 0.41). Only the measure of general trust showed satisfactory convergent validity with the AVE greater than the cut-off point of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). However, the convergent validity for social participation and subjective wellbeing measures can still be considered adequate, given that their AVEs are close to the threshold and have composite reliabilities greater than 0.60 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Structural Model

An examination of the direct relationship between study variables while controlling for sociodemographic variables showed that general trust was positively related to SWB (β = 0.32, p < .001), social participation (β = 0.28, p < .001), and social resources (β = 0.26, p < .001). In addition, social participation (β = 0.28, p < .001) was positively associated with social resources (β = 0.51, p < .001) and SWB (β = 0.41, p < .001). The direct relationship between social resources and SWB was positive (β = 0.21, p < .001).

Independent Mediation Analyses

Initially, three separate mediation analyses were performed (see Table 3). First, the indirect effect of general trust on SWB through social participation was tested. Results showed that the standardised total effect of general trust on SWB was significant (β = 0.39, p < .001). The mediating effect of social participation on the relationship between general trust and SWB was also significant [β = 0.08, 95% CI (0.06, 0.09)]. Second, the indirect effect of general trust on SWB through social resources was tested. The standardised total effect of general trust on SWB was also significant (β = 0.40, p < .001). The mediating effect of social resources on the relationship between general trust and SWB was also found to be significant [β = 0.03, 95% CI (0.02, 0.04)]. In the third mediation analysis, the indirect effect of general trust on SWB sequentially through social participation and social resources were examined. Results indicated that the standardised total effect of general trust on SWB was significant (β = 0.41, p < .001). The sequential mediating effect of social participation and social resources was further confirmed [β = 0.03, 95% CI (0.02, 0.03)].

Full Mediation Analyses

The full mediation model indicating the direct and indirect paths are depicted in Fig. 2 with standardised estimates. Gender, age, education, and household size were included in the model as control variables. The model achieved a satisfactory fit, χ2 (45) = 2010.01, p < .001; SRMR = 0.05; CFI = 0.903 and RMSEA = 0.072 [90% CI = (0.072, 0.075)]. The direct paths from general trust to social participation (β = 0.25, p < .001), social resources (β = 0.12, p < .001), and SWB (β = 0.31, p < .001) were all significant. The direct paths from social participation to social resources (β = 0.45, p < .001) and SWB (β = 0.32, p < .001) were also significant. However, the path from social resources to SWB became non-significant (β = 0.004, p = .77). Table 2 shows the results of the test of mediation. While the mediation effect of social participation [B = 0.01, 95% CI (0.01, 0.013)] was significant, the mediation effect of social resources was not [B = 0.00, 95% CI (-0.004, 0.003)]. In addition, the sequential mediating effect of social participation and social resources on the relationship between general trust and wellbeing was not confirmed [B = 0.00, 95% CI (-0.004, 0.003)].

Discussion

While research often focuses on individual social determinants and their impact on health, this study examined how different aspects of social connectedness interact and influence wellbeing. The current study examined the relationship between general trust, social participation, social resources and SWB using data from 8725 participants pooled from the German part of the ESS Wave 10 (ESS, 2023). Structural models were estimated to assess the path from general trust to subjective wellbeing. The results confirm significant indirect effects of general trust on SWB independently through (1) social participation, (2) social resources, and (3) and serially via social participation and social resources. However, the full mediation analyses showed that social participation significantly mediated the relationship between general trust and subjective wellbeing in this sample, while social resources did not. In addition, the initial serial mediation effect obtained in the independent model was not supported, given that the path from social resources to SWB became non-significant. This suggests that social participation already accounts for the direct relationship between social resources and SWB. This confirms previous findings highlighting the importance of social participation in promoting SWB (Diener, 2021; Ferrari, 2022; Schmiedeberg & Schröder, 2017).

Furthermore, the statistical significance of the direct paths from general trust to social participation, social resources, and SWB in the independent models suggest that individuals who generally believe that people are mostly reliable and would act in one’s interest are more likely to engage in more social activities, have more access to social resources, and consequently, a higher level of SWB. In contrast, individuals having low levels of general trust may be less likely to engage in social interactions, be more cautious and guarded in their interactions with others and may experience greater social isolation or loneliness. This study’s findings are in line with previous studies reporting that individuals who have higher levels of general trust tend to have more positive social and health outcomes (Adedeji et al., 2021a, b; Hamamura et al., 2017; Jen et al., 2010; Kawachi et al., 1999; Nummela et al., 2012; Yip et al., 2007). For example, Adedeji et al. (2021a, b) showed that trust and sociability are essential in enhancing the quality of life among Sub-Saharan African migrants in Germany. General trust can be considered a crucial aspect of interpersonal interactions and relationships and proved to be one of the most robust predictors of SWB (Helliwell & Wang, 2010).

Additionally, it was found that the direct paths from social participation to social resources and SWB were also significant. This suggests that engaging in social activities, such as volunteering and attending social events, can increase social resources and a greater sense of SWB. Social participation provides opportunities for individuals to build and strengthen their social networks, which can, in turn, provide access to resources, such as emotional and social support, practical assistance, and access to information and resources. Additionally, social participation may provide opportunities for individuals to engage in activities that promote positive emotions and thus increase SWB (Adedeji, Silva et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). The study findings complement previous research where social participation was identified as a predictor of quality of life (Adedeji et al., 2021a, b; Guo et al., 2018; Santini et al., 2020).

Full mediation analyses showed that while the mediation effect of social participation on the relationship between general trust and SWB was significant, the mediation effect of social resources was not. As hypothesised, this suggests that in this sample, social participation acts as a pathway through which general trust influences SWB. People with higher levels of general trust may be more likely to engage in social participation activities, leading to higher levels of SWB (Ahamed & Noboa, 2022; Sabetzadeh & Chen, 2023; Wu et al., 2009). Previous research has also shown that general trust can facilitate feeling more connected to others, promoting happiness and quality of life (Adedeji et al., 2021a, b; Bjørnskov, 2008; Tokuda et al., 2010). Trusting people can lead to building strong and supportive relationships with others. The quality of social relationships is one of the consistent predictors of SWB (Diener & Seligman, 2002).

The mediation effect of social resources, however, was not significant, indicating that social resources did not have a uniquely significant contribution in mediating the relationship between general trust and subjective wellbeing that is not already accounted for by social participation. In other words, the results suggest that although social resources may be essential for SWB, the effect is already captured by social participation. Therefore, increasing social participation may be more effective in promoting wellbeing than simply increasing social resources. In other words, “saving up” social resources may not benefit SWB but rather engage in activities with these resources. This exciting result explains the unique contribution of social participation and social resources to SWB in the German context. It is possible that engaging in social activities built on trust, for example, volunteering, attending community gatherings, or spending time with friends and family, already covers all the advantages of social resources. There is no previous empirical analysis of this path; however, other researchers have argued that social participation and social resources as interrelated concepts that may have similar effects on life outcomes (Levasseur et al., 2015; Richard et al., 2013; Simplican et al., 2015). These studies have argued that social participation can lead to increased access to social resources, and in turn, social resources can facilitate greater social participation (Piškur et al., 2014b). Based on the current finding, we argue that social participation rooted in general trust functions as social resources to promote SWB.

Theoretical Contributions

Examining the mediating roles of social participation and resources offers a refined understanding of how trust in others can impact individuals’ wellbeing. Furthermore, the findings emphasise the importance of active engagement and involvement in social activities as a pathway through which trust positively influences wellbeing.

The study challenges the initial assumption suggesting that social resources accounts for the relationship between social participation and subjective wellbeing (Chen & Zhang, 2021; He et al., 2022). By finding the direct relationship between social resources and wellbeing to be non-significant when social participation is considered, the study suggests that the effects of social resources on wellbeing is already explained by social participation. In order words, the number of social resources available to individuals may not be the essential pathway to wellbeing but rather the extent people engage in social activities.

By confirming the role of social participation as a significant mediator in the relationship between general trust and wellbeing, the study strengthens the theoretical foundations of previous research conducted by Diener (2021), Ferrari (2022), and Schmiedeberg and Schröder (2017). Overall, the findings refine existing theoretical frameworks and shed light on the specific pathways through which trust operates to influence individuals’ wellbeing.

Practical Implication

The findings underscore the significance of social participation in enhancing subjective wellbeing. Encouraging individuals to actively engage in social activities, such as joining community groups, volunteering, or participating in recreational activities, can benefit their overall wellbeing (Sheppard & Broughton, 2020). Similarly, as general trust was a significant predictor of subjective wellbeing, efforts to build trust in communities and society can contribute to improved wellbeing outcomes. Strategies promoting interpersonal trust, such as transparency, fairness, and accountability in institutions, can be valuable for creating environments where trust can thrive (Meijer & Grimmelikhuijsen, 2020).

While social resources did not significantly contribute to wellbeing in the full mediation model, it appears to be protective in the independent model strengthening social resources, such as access to social support networks, community services, and resources for personal development, can have positive implications for individuals’ subjective wellbeing (Yıldırım & Tanrıverdi, 2021). Also, study findings provide insights into the mechanisms linking trust, social participation, and wellbeing. It is crucial to consider different populations’ diverse needs and characteristics when designing interventions. For instance, interventions targeted at vulnerable or marginalised groups may need to address specific barriers to social participation and provide tailored support to enhance trust and wellbeing (Skivington et al., 2021). Understanding the unique contexts and challenges different populations face can help inform the development of effective interventions.

Creating positive social environments that foster trust, cooperation, and meaningful social connections can have far-reaching effects on individuals’ wellbeing. Organisations, institutions, and communities can promote inclusive and supportive environments that encourage social interactions, collaboration, and mutual support. This can be achieved through initiatives such as promoting positive social norms that enhance trust, fostering inclusive policies and practices, and providing opportunities for social engagement and participation. Collectively, this study suggests the importance of promoting building trust, social participation,, enhancing social resources, tailoring interventions, and creating positive social environments to improve individuals’ wellbeing and quality of life. By implementing these strategies, policymakers, communities, and organisations can contribute to the wellbeing of individuals and foster happier and more fulfilling lives.

Limitations

The current analysis contributes to the empirical understanding of the path between general trust, social participation, social resource and SWB. Despite the robust sample size, the findings should be interpreted within certain conceptual and methodological limitations.

In discussing the limitations of this study, it is essential to adopt a critical and self-critical approach. First, one limitation concerns employing measures with a single item measure of social resources and a few items, which may not capture the complexity of other constructs under investigation. However, it is suggested that a single-item measure is sufficient to assess a unidimensional construct that is easily comprehensible (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, 2009; Sauro, 2018) such as asking the number of people one can discuss personal and intimate matter with. In addition, the study’s latent constructs are shown to have adequate reliability and validity. While these measures have been argued to provide subjective insight into intended constructs future studies should consider employing instruments with multiple items to provide a more robust assessment.

Furthermore, this study employed a cross-sectional design, which limits our ability to establish causal relationships between variables. For example, social participation and resources may shape general trust and subjective wellbeing. While our findings suggest a positive association between general trust and subjective wellbeing, alternative explanations for other aspects of social capital and social connectedness, e.g., locus of control, solidarity, or social cohesion, can not be ignored. Future research could employ longitudinal or experimental designs to better understand these constructs’ temporal dynamics and causal relationships.

Moreover, it is essential to note that this study focused on a specific population and context, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Cultural, socioeconomic, and demographic factors can influence the relationship between general trust and subjective wellbeing. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating the results to other populations or contexts. Replication studies in diverse populations are warranted to validate the generalizability of these findings.

Lastly, despite efforts to control for confounding variables, it is possible that unmeasured factors may influence the observed relationships. For instance, individual differences in personality traits or life circumstances may have influenced both general trust and subjective wellbeing. Future research should consider incorporating additional potential confounders.

Conclusion

The current analysis provides a unique insight into the path linking general trust to SWB through social participation and social resources in a German sample. Overall, social participation and social resources are mutually reinforcing. Individuals with both are likely to experience better health, wellbeing, and social connectedness outcomes. However, a complete model highlights social participation as the single unique significant mediator of the association between general trust and SWB. Thus, general trust and social participation are crucial for individual wellbeing as they facilitate building and maintaining personal and professional relationships. When people trust one another, they are more likely to cooperate, share resources, and support one another.

The findings provide policymakers, researchers, and social and health workers with evidence-based models to improve SWB. Finally, the results underscored the need to encourage social participation, enable cooperation, and build trust.

Data Availability

The analysed data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Adedeji, A., Akintunde, T. Y., Idemudia, E. S., Ibrahim, E., & Metzner, F. (2021a). Trust, sociability, and Quality of Life of Sub-Saharan African Migrants in Germany. Frontiers in Sociology, 6, 741971. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021a.741971.

Adedeji, A., Silva, N., & Bullinger, M. (2021b). Cognitive and structural Social Capital as Predictors of Quality of Life for Sub-Saharan African Migrants in Germany. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16(3), 1003–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09784-3.

Ahamed, A. J., & Noboa, F. (2022). Interconnectedness of trust-commitment-export performance dimensions: A model of the contingent effect of calculative commitment. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2088461. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2088461.

Ang, S. (2018). Social Participation and Mortality among older adults in Singapore: Does ethnicity explain gender differences? The Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(8), 1470–1479. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw078.

Arbor, A. (1971). The 1964 SRC election study (S473). Inter-university Consortium for Political Research.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 74–94.

Bjørnskov, C., & Happiness in the United States. (2008). Social Capital and. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 3(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-008-9046-6.

Bottoni, G. (2018). A Multilevel Measurement Model of Social Cohesion. Social Indicators Research, 136(3), 835–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1470-7.

Brereton, F., Bullock, C., Clinch, J. P., & Scott, M. (2011). Rural change and individual well-being: The case of Ireland and rural quality of life. European Urban and Regional Studies, 18(2), 203–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411399346

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative Ways of assessing Model Fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005.

Campbell, K. E., Marsden, P. V., & Hurlbert, J. S. (1986). Social resources and socioeconomic status. Social Networks, 8(1), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(86)80017-X.

Chen, L., & Zhang, Z. (2021). Community Participation and Subjective Wellbeing: Mediating Roles of Basic Psychological Needs Among Chinese Retirees. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.743897.

Cislaghi, B., & Cislaghi, C. (2019). Self-rated health as a valid indicator for health-equity analyses: Evidence from the italian health interview survey. Bmc Public Health, 19(1), 533. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6839-5.

Dahlgren, G., Whitehead, M., & World Health Organization Regional Office of Europe. (2006). &. Levelling up (part 2): A discussion paper on European strategies for tackling social inequities in health / by Göran Dahlgren and Margaret WHitehead Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107791.

Diener, E. (2021). Happiness: The Science of Subjective Well-Being. DEF publishers. https://nobaproject.com/modules/happiness-the-science-of-subjective-well-being.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415.

Diener, E., Lucas, R., Helliwell, J. F., & Schimmack, U. (2009). Well-being for public policy. Oxford Positive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195334074.001.0001.

Dixon, J., & McKeown, S. (2021). Negative contact, collective action, and social change: Critical reflections, technological advances, and new directions. Journal of Social Issues, 77(1), 242–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12429.

Dorer, B. (2012). ESS Round 6 Translation Guidelines.

Dyar, O. J., Haglund, B. J. A., Melder, C., Skillington, T., Kristenson, M., & Sarkadi, A. (2022). Rainbows over the world’s public health: Determinants of health models in the past, present, and future. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(7), 1047–1058. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948221113147.

Edward, L., José, G. D. I. L. A., S., & Christine, L., S (2000). Measuring Trust. Quarterly Journal of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554926.

Escalera-Reyes, J. (2020). Place attachment, feeling of belonging and collective identity in Socio-Ecological Systems: Study Case of Pegalajar (Andalusia-Spain). Sustainability, 12(8), https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083388. Article 8.

ESS (2023). European Social Survey | European Social Survey (ESS). https://ess-search.nsd.no/.

Ferrari, G. (2022). What is wellbeing for rural south african women? Textual analysis of focus group discussion transcripts and implications for programme design and evaluation. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01262-w.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Sage CA.

Fuchs, C., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2009). Using single-item measures for construct measurement in management research. Die Betriebswirtschaft, 69(2), 195–210.

Guillen, L., Coromina, L., & Saris, W. E. (2011). Measurement of Social Participation and its place in Social Capital Theory. Social Indicators Research, 100(2), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9631-6.

Guo, Q., Bai, X., & Feng, N. (2018). Social participation and depressive symptoms among chinese older adults: A study on rural–urban differences. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.036.

Haddock, C. K., Poston, W. S., Pyle, S. A., Klesges, R. C., Weg, V., Peterson, M. W., A., & Debon, M. (2006). The validity of self-rated health as a measure of health status among young military personnel: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-57.

Hamamura, T., Li, L. M. W., & Chan, D. (2017). The Association between Generalized Trust and Physical and Psychological Health Across Societies. Social Indicators Research, 134(1), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1428-9.

Hamel, N. (2022). Social Participation of Students with a Migration Background—A comparative analysis of the beginning and end of a School Year in german primary schools. Frontiers in Education, 7, 75.

He, X., Shek, D. T., Du, W., Pan, Y., & Ma, Y. (2022). The relationship between Social Participation and Subjective Well-Being among older people in the Chinese Culture Context: The mediating effect of reciprocity beliefs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16367.

Helliwell, J. F., & Wang, S. (2010). Trust and well-being. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2016). New evidence on trust and well-being. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of Political Trust. The American Political Science Review, 92(4), 791–808. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586304.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jen, M. H., Sund, E. R., Johnston, R., & Jones, K. (2010). Trustful societies, trustful individuals, and health: An analysis of self-rated health and social trust using the World Value Survey. Health & Place, 16(5), 1022–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.008.

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., & Glass, R. (1999). Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 89(8), 1187–1193. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.89.8.1187.

Khan, K. S., Mamun, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., & Ullah, I. (2022). The Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across different cohorts. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(1), 380–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00367-0.

Kim, D. H., & Ellison, N. B. (2022). From observation on social media to offline political participation: The social media affordances approach. New Media & Society, 24(12), 2614–2634.

Kwon, O. Y. (2019). Social trust: Its concepts, determinants, roles, and raising ways. In Social Trust and Economic Development (pp. 19–49). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.elgaronline.com/display/9781784719593/chapter01.xhtml.

Levasseur, M., Richard, L., Gauvin, L., & Raymond, E. (2010). Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: Proposed taxonomy of social activities. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 71(12), 2141–2149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.041.

Levasseur, M., Généreux, M., Bruneau, J. F., Vanasse, A., Chabot, É., Beaulac, C., & Bédard, M. M. (2015). Importance of proximity to resources, social support, transportation and neighborhood security for mobility and social participation in older adults: Results from a scoping study. Bmc Public Health, 15(1), 503. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1824-0.

Lin, K., & Herrmann, P. (Eds.). (2015). Social Quality Theory: A New Perspective on Social Development (1st ed.). Berghahn Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv6jmwcs.

Liu, Q., Pan, H., & Wu, Y. (2020). Migration status, internet use, and social participation among middle-aged and older adults in China: Consequences for depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 6007.

Meijer, A., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2020). Responsible and accountable algorithmization: How to generate citizen trust in governmental usage of algorithms. The Algorithmic Society (pp. 53–66). Routledge.

Mironova, A. A. (2015). Trust, social capital, and subjective individual well-being. Sociological Research, 54(2), 121–133.

Mohammed, A., & Ferraris, A. (2021). Factors influencing user participation in social media: Evidence from twitter usage during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Technology in Society, 66, 101651.

Murray Nettles, S., Mucherah, W., & Jones, D. S. (2000). Understanding resilience: The role of Social Resources. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 5(1–2), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2000.9671379.

Neugarten, B. L., Havighurst, R. J., & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 16(2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/16.2.134.

Norman, H., Nordin, N., Din, R., Ally, M., & Dogan, H. (2015). Exploring the roles of social participation in mobile social media learning: A social network analysis. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(4), 205–224.

Nummela, O., Raivio, R., & Uutela, A. (2012). Trust, self-rated health and mortality: A longitudinal study among ageing people in Southern Finland. Social Science & Medicine, 74(10), 1639–1643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.010.

Olonisakin, T. T., & Idemudia, E. S. (2022). Psycho-social correlates of wellbeing among South Africans: An exploration of the 2017 south african Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS). Acta Psychologica, 231, 103792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103792.

Olonisakin, T. T., & Idemudia, E. S. (2023). Determinants of support for social integration in South Africa: The roles of race relations, social distrust, and racial identification. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 33(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2644.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946.

Pinillos-Franco, S., & Kawachi, I. (2018). The relationship between social capital and self-rated health: A gendered analysis of 17 european countries. Social Science & Medicine, 219, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.010.

Piškur, B., Daniëls, R., Jongmans, M. J., Ketelaar, M., Smeets, R. J., Norton, M., & Beurskens, A. J. (2014a). Participation and social participation: Are they distinct concepts? Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(3), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215513499029.

Piškur, B., Daniëls, R., Jongmans, M. J., Ketelaar, M., Smeets, R. J., Norton, M., & Beurskens, A. J. (2014b). Participation and social participation: Are they distinct concepts? Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(3), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215513499029.

Ravulo, J., Said, S., Micsko, J., & Purchase, G. (2020). Social value and its impact through widening participation: A review of four programs working with primary, secondary & higher education students. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1722307.

Rice, L., & Sara, R. (2019). Updating the determinants of health model in the information age. Health Promotion International, 34(6), 1241–1249. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day064.

Richard, L., Gauvin, L., Kestens, Y., Shatenstein, B., Payette, H., Daniel, M., Moore, S., Levasseur, M., & Mercille, G. (2013). Neighborhood Resources and Social Participation among older adults: Results from the VoisiNuage Study. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(2), 296–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264312468487.

Sabetzadeh, F., & Chen, Y. (2023). An investigation of the impact of interpersonal and institutional trust on knowledge sharing in companies: Invisible hands for knowledge sharing. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-06-2022-0206.

Santini, Z. I., Jose, P. E., Koyanagi, A., Meilstrup, C., Nielsen, L., Madsen, K. R., & Koushede, V. (2020). Formal social participation protects physical health through enhanced mental health: A longitudinal mediation analysis using three consecutive waves of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Social Science & Medicine, 251, 112906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112906.

Sauro, J. (2018). Is a single item enough to measure a construct?https://measuringu.com/single-multi-items/.

Sharpe, A. (1999). A survey of indicators of economic and social well-being. Centre for the Study of Living Standards Ottawa.

Sheppard, A., & Broughton, M. C. (2020). Promoting wellbeing and health through active participation in music and dance: A systematic review. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1732526.

Simplican, S. C., Leader, G., Kosciulek, J., & Leahy, M. (2015). Defining social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and community participation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 18–29.

Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., & McIntosh, E. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. Bmj, 374.

Søvold, L. E., Naslund, J. A., Kousoulis, A. A., Saxena, S., Qoronfleh, M. W., Grobler, C., & Münter, L. (2021). Prioritizing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Healthcare Workers: An Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Frontiers in public health, 9, 679397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.679397.

Swader, C. S. (2019). Loneliness in Europe: Personal and societal individualism-collectivism and their connection to social isolation. Social Forces, 97(3), 1307–1336. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy088.

Tokuda, Y., Fujii, S., & Inoguchi, T. (2010). Individual and Country-Level Effects of Social Trust on Happiness: The Asia Barometer Survey. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(10), 2574–2593. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00671.x.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00292648.

Wang, R., Feng, Z., Liu, Y., & Lu, Y. (2020). Relationship between neighbourhood social participation and depression among older adults: A longitudinal study in China. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(1), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12859.

Ward, P., & Meyer, S. (2009). Trust, Social Quality and Wellbeing: A sociological exegesis. Development and Society, 38(2), 339–363.

Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation (pp. xxii, 236). The MIT Press.

Wu, W. L., Lin, C. H., Hsu, B. F., & Yeh, R. S. (2009). Interpersonal trust and knowledge sharing: Moderating effects of individual altruism and a social interaction environment. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 37(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2009.37.1.83.

Yamagishi, T. (1986). The provision of a sanctioning system as a public good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(1), 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.110.

Yip, W., Subramanian, S. V., Mitchell, A. D., Lee, D. T. S., Wang, J., & Kawachi, I. (2007). Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China. Social Science & Medicine, 64(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.027.

Yıldırım, M., & Tanrıverdi, F. (2021). Social support, resilience and subjective well-being in college students. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 5(2), 127–135.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding was received for this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Statement

All procedures were guided by the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

The current analysis uses secondary data from the European Social Survey (ESS) Wave 10. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Adekunle Adedeji and Babatola Dominic Olawa shared first authorship.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adedeji, A., Olawa, B., Hanft-Robert, S. et al. Examining the Pathways from General Trust Through Social Connectedness to Subjective Wellbeing. Applied Research Quality Life 18, 2619–2638 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10201-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10201-z