Abstract

Depression contributes to disability more than any other mental disorder and is associated with a reduced health-related quality of life. However, the impact of depression on the social environment is relatively unknown. The current study determined differences in the health-related quality of life between co-living household members of depressed persons and persons in households without depression. Furthermore, factors influencing the health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons were evaluated. Using a sample of the German Socio-Economic Panel, health-related quality of life was measured longitudinally with the 12 item Short Form health survey. In addition to descriptive statistics, differences in health-related quality of life and factors influencing the health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons were determined by mixed effects beta regressions. Mental health-related quality of life was reduced for co-living household members of depressed persons compared with persons of households without depressed persons. Health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons was lower for women compared to men as well as for widowed persons compared to married persons. Overall, the health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons was reduced, which might be due to increased stress levels. It is therefore important to focus on support services for people in the social environment of depressed persons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide, 300 million persons suffered from depression in the year 2015 (Word Health Organisation, 2017). Thereby, depression contributed to disability more than every other mental illness (Word Health Organisation, 2017). Based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, depression is diagnosed by depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in activities in daily life for at least two weeks (Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.: DSM-V. 2013). In turn, depressed persons often feel down and listless, and in severe cases even tend to commit suicide. Overall, 50% of all suicides in the United States could be attributed to depression, making depression the tenth leading cause of death (Kessler et al., 2012). Furthermore, depressed persons often suffer from additional mental and somatic disorders, such as dorsopathies, hypertension or metabolic disorders (Steffen et al., 2020). In this context, depression can trigger other diseases and vice versa, so that it is often associated with chronic diseases including cancer and cardiovascular, metabolic, inflammatory and neurological disorders (Gold et al., 2020).

As varied as the reasons for depression may be, so is its course of disease. Often, the onset of a depression is described as occurring in adolescence, with the medical diagnosis coming years later (Parker & Brotchie, 2010; Stegenga et al., 2012). Delayed diagnosis of depression is particularly common in persons with co-existing chronic diseases (Gagliese et al., 2007; Seritan et al., 2019). Overall, women are affected by depression twice as often as men (Parker & Brotchie, 2010; Stegenga et al., 2012). Usually, treatment with psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy follows the diagnosis (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2010). According to a systematic review, adequate treatment led to remission after 4 and 16 months in 14% and 88% of the cases, respectively (Richards, 2011). After 10 to 15 years, however, only 7% of the treated patients were still without symptoms of depression. Thus, relapses and recurrences during the course of depression are quite likely.

Beyond the primary aim of reducing clinical symptoms of depression, adequate treatment also aims to improve (health-related) quality of life and social interactions, so that interest and pleasure in activities in daily life are increased (Kamenov et al., 2017). In particular, persons with major depression were more likely to rebuild their daily and social activities than persons with minor depression and consequently improved in their health-related quality of life more (Kamenov et al., 2017). However, as social interactions are highly influenced by depression, depression may also affect health and health-related quality of life of non-depressed persons in the depressed person’s social environment.

So far, hardly any consequences of depression on non-depressed persons in the social environment of depressed persons have been described in the literature. Occasionally, associations between depression of adolescents and the family environment have been reported (Hammen et al., 2003; Sheeber et al., 1998). In addition, stress levels have been shown to increase in caregivers and family members of depressed persons (Hammen et al., 2004; Scerri et al., 2019). Beyond that, little is known about the effects on health and health-related quality of life of persons living in the social environment of depressed persons.

Therefore, this study examined the health-related quality of life among co-living members in households with depressed persons. Based on data from the German Socio-Economic Panel, a representative national survey of German households, two research questions were investigated: Does the health-related quality of life of co-living members in households with depressed persons differ from the health-related quality of life of persons in households without depressed persons (research question 1)? If there was a difference in health-related quality of life, what were the determinants of health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons (research question 2)?

Methods

Data

The German Socio-Economic Panel data is derived from an annual representative survey of more than 20,000 German households, which has been conducted since 1984. Thus, 34 waves have been available so far. In order to ensure the representativeness not only of the households but also of the household members, the German Socio-Economic Panel aims to survey as many members of one household as possible. Consequently, 95% of the households were fully interviewed (Bohlender et al., 2018). In addition, the sample is regularly updated, so that underrepresented groups of people, such as persons who lived in the former German Democratic Republic before 1990 or migrants, have been included and imbalances due to the death of survey participants have been reduced. To ensure data quality of the German Socio-Economic Panel, difficult questions were continually improved and the survey data was checked for completeness, consistency and plausibility by the German Institute for Economic Research, Berlin, and if necessary, inquiries were clarified via phone calls with the panel participants (Bechmann & Sleik, 2016).

The German Institute for Economic Research provides pre-processed data form the German Socio-Economic Panel, so-called core datasets, for certain groups of people. For the present analyses, the core datasets of the household surveys as well as the datasets on health and biography of the adult household members were used. Analyses were based on core datasets from waves 26–34, which were surveyed during the years 2010 to 2018. Restrictions to these waves were necessary because within the German Socio-Economic Panel, health-related quality of life has only been surveyed every even year since 2006 (wave 22) and diagnosis of depression has only been surveyed every odd year since 2009 (wave 25), respectively. Furthermore, the data were limited to adult household members, as the health-related quality of life of minor household members was not surveyed within the German Socio-Economic Panel.

Health aspects and socio-demographic characteristics were surveyed by self-disclosure of individual household members. Information on age, gender, marital status, educational level, number of diseases, household size, and death of a household member was available from the core data sets. As the German education system differs from international education systems, educational level was specified by the duration of education being related to German degrees. Additionally, the number of diseases such as sleep disorder, diabetes, asthma, cardiac disease, cancer, stroke, migraine, high blood pressure, dementia, joint diseases, and chronic back pain was calculated.

The diagnosis of depression was surveyed by self-disclosure based on the question “Has a doctor ever diagnosed you to have depression?”. Due to the delay in diagnosis after the onset of depression, data up to four years before the actual diagnosis were considered in the present analyses. In addition, data two years after the actual diagnosis of depression were used. No further consideration was made with respect to diagnosis of depression, as no information on the severity and treatment status was collected within the German Socio-Economic Panel. Thus, persons recovered from depression could not be identified.

For the differentiation between households with and without depressed persons, the core dataset of the household survey with information on household composition was used. Members of households without depressed persons had to have disagreed with the question “Has a doctor ever diagnosed you to have depression?”.

Health-related quality of life

Within the German Socio-Economic Panel, health-related quality of life was measured using the 12 item Short Form health survey, which comprises 12 questions rated on a three- to five-point Likert scale (Andersen et al., 2007; Schupp et al., 2007; Ware et al., 1996) (Appendix: Table S1). For the present analyses, three sum scores were calculated based on the 12 items of the 12 item Short Form health survey: the physical component summary, the mental component summary, and the SF-6D index. The physical component summary summarizes questions on physical health, impaired physical role function, physical pain and vitality, while the mental component summary summarizes questions on mental health, limited emotional role function and social functioning. In order to determine these two sum scores, the data obtained were z-transformed using means and standard deviations of a normative sample of the German population (Nübling et al., 2006; Schupp et al., 2007). The resulting physical component summary scores and mental component summary scores represent the physical and mental health-related quality of life on a scale between 0 (worst health-related quality of life) and 100 (best health-related quality of life), respectively.

In addition, an index measure, the SF-6D index, was based on the questions of physical health, limited physical/emotional role function, physical pain, vitality, mental health, and social functioning. For this, the preference-based value set of the British population was used to reflect health-related quality of life of the 7500 possible health states on a scale between 0 (death) and 1 (full health) (Brazier & Roberts, 2004).

Statistical analyses

The number of missing values was reduced by replacement with data from other waves whenever possible. Especially for the health-related quality of life scores (physical component summary, mental component summary and SF-6D index) a high proportion of up to 13% of missing values was present, while in socio-demographic variables only a few missing values remained after data cleaning. Therefore, missing values were replaced by multiple imputation by chained equations using predictive mean matching, so that finally n = 10 imputed data sets were generated as basis for the analyses (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011).

The analyses included descriptive statistics of socio-demographic characteristics as well as of health-related quality of life. In addition, the health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons was compared to the health-related quality of life of persons in households without depressed persons using mixed effects regression models (research question 1). In the models, health-related quality of life was integrated as dependent variable, whereas the household membership was binary coded, and integrated together with socio-demographic characteristics as independent variables. Likewise, determinants of health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons were examined using mixed effects regression models, in which only socio-demographic variables were included as independent variables without the binary-coded household membership variable (research question 2). Random effects were used in the models to account for individuals’ health-related quality of life over time. As residuals were not normally distributed and the application of the bootstrap method was not possible due to the large sample size, mixed effects models were calculated assuming a beta distribution of the dependent variable with a logit-link function. As the beta distribution is scaled between 0 and 1, the mental and physical component summary scores were transformed by dividing them by 100. Subsequently, coefficients were exponentiated (exp(β)), so that they can be interpreted as the change in the odds for the respective health-related quality of life variable. A coefficient above 1.00 may thus represent an increased health-related quality of life, while the health-related quality of life may be decreased for coefficients smaller than 1.00.

In addition, all previously mentioned analyses were repeated using data of complete cases to check the robustness of the results based on multiply imputed data.

All analyses were performed using R 3.5.1. The package “mice” was used for multiple imputation and the package “glmmTMB” was used for calculating mixed effects models based on beta regressions. All applied statistics were two-sided.

Results

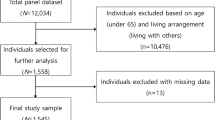

In total, the sample of households with depressed persons included N = 1058 households with n = 1290 co-living non-depressed adult household members, whereas the sample of households without depressed persons (n = 16,051) included N = 11,985 households. Co-living household members of depressed persons were on average 39.98 (SD 14.56) years old, with 60.23% persons being male. In households without depressed persons, household members were on average 43.52 (SD 13.88) years old and about 47.69% of all persons were male. In both household groups, the majority of persons were married or single (93.29% and 89.10%, respectively), and most persons had completed 10 years of school or less (48.15% and 50.76%, respectively). Further details on socio-demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Co-living household members of depressed persons reported a mean physical component summary score of 54.15 (SD 7.03), a mean mental component summary score of 50.43 (SD 9.01) and a mean SF-6D index score of 0.76 (SD 0.12; Table 1). The corresponding scores for persons in households without depressed persons were 53.93 (SD 7.13), 51.78 (SD 8.64) and 0.78 (SD 0.12), respectively.

Mixed effects models showed statistically significantly different health-related quality of life measures in terms of physical component summary scores, mental component summary scores and SF-6D index scores between co-living household members of depressed persons and persons in households without depressed persons (Table 2). Thereby, the SF-6D index was statistically significantly reduced for co-living household members of depressed persons compared with persons in households without depressed persons (exp(β) = 0.89, p < 0.001). Likewise, reduced mental component summary scores were observed for co-living household members (exp(β) = 0.95, p < 0.001). Although statistically significant, differences in physical component summary scores between the two household groups were small (exp(β) = 0.99, p = 0.022).

In terms of mental health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons, mental component summary scores were statistically significantly associated with survey year, age, gender and marital status in the mixed effects model (Table 3). Mental component summary scores were statistically lower for female co-living household members of depressed persons than for male household members (exp(β) = 0.92, p < 0.001). Widowed co-living household members of depressed persons had lower mental component summary scores compared with married household members (exp(β) = 0.79, p = 0.010). Although statistically significant, differences in mean mental component summary scores for survey year (exp(β) = 1.00, p < 0.001) and an older age (exp(β) = 1.00, p < 0.001) were small.

In terms of physical health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons, physical component summary scores were statistically significantly associated with educational level and number of diseases. Co-living household members of depressed persons with higher educational level had higher physical component summary scores than compared with household members without graduation (exp(β) = 1.09, p < 0.001), whereas the physical component summary score decreased with a higher number of diseases (exp(β) = 0.97, p < 0.001).

In terms of the SF-6D index, female co-living household members of depressed persons had a lower score than male household members (exp(β) = 0.81, p < 0.001). All other sociodemographic parameters added were not statistically significant in the mixed effects regression models. In particular, the number of diseases of the depressed person was not statistically significantly associated with the health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons (data not shown).

Results of complete case analyses were similar to those of the multiply imputed data, thus the results seemed to be robust.

Discussion

The present study was able to show a reduced health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons compared with persons in households without depressed persons. Although the physical health-related quality of life was significantly reduced for co-living household members of depressed persons compared with persons in households without depressed persons, the differences were small. Thus, the reduced health-related quality of life was most likely due to a reduced mental health-related quality of life rather than due to the physical health-related quality of life.

Previous literature focused mainly on the health-related quality of life of the depressed person, but did not consider the health-related quality of life of persons in the social environment. However, health-related effects among people in the social environment of depressed persons are well known. For example, family members of depressed persons are more likely to be affected by depression themselves (Hawton et al., 2013; Jääskeläinen et al., 2018). Furthermore, increased stress levels were observed among caregivers and family members of depressed persons (Scerri et al., 2019). In this context, stress itself can have far-reaching consequences for physical and mental health, such as cardiovascular diseases, burnout or depressive mood (Yaribeygi et al., 2017). Consequently, stress might be responsible for a reduced mental health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons in the current study.

Considering socio-demographic factors influencing the health-related quality of life of co-living household members, especially female co-living household members of depressed persons had a lower health-related quality of life compared to males. In the present sample, predominantly women (69%) suffered from depression, which approximately corresponds to the 2:1 prevalence ratio of depression between men and women (Albert, 2015; Salk et al., 2017). In addition to the higher prevalence among women, more severe courses of depression were reported to be more frequent in women than in men (Picco et al., 2017). Unfortunately, information on the severity of depression was not included in the German Socio-Economic Panel. However, as the German Socio-Economic Panel is representative for German households, it is conceivable that females with depression were more affected than males in the present sample. Thus, the higher prevalence of depression among women might have led to differences in health-related quality of life between female and male co-living household members. One reason for this could be that task of the depressed person were taken over by other household member. Furthermore, gender-specific coping strategies in dealing with stress, which have already been discussed in literature (Meléndez et al., 2012; Rubio et al., 2016), might also be relevant in dealing with a depressed person in the household. An improvement in depressive symptoms and in turn a reduction in stress might therefore be important for improving health-related quality of life. Persons in the social environment of a depressed person are encouraged to look out for signs of depression, offer support and help to the depressed person, have active contact with the depressed person and be patient (National Health Service, 2018). In addition, support services such as support groups and self-help telephone hotlines can be useful in coping with stressful situations for both the depressed person and the persons in the social environment.

In addition to gender, the marital status significantly influenced health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons. Since only adults were considered in the present analyses, it can be assumed that marital status is closely related to the family role in the household. In the current sample, more children and adolescents lived in households with only one other adult besides the depressed person, whereas less children and adolescents lived in households with at least two additional adults besides the depressed person. Co-living adult household members of depressed persons without support by other adults may thus be increasingly taking over household tasks as well as for the care of the children, insofar as the depressed person is no longer sufficiently capable of performing these tasks. However, the exact family role was not surveyed in the German Socio-Economic Panel, so that the relationship between the co-living household members and the depressed person could not be investigated further. In addition, as the sample size of widowed and separated co-living household members was very small (n = 10 and n = 11, respectively), this finding may rather be interpreted as preliminary.

Implications and future research

Within this study, the extended perspective of the social environment revealed a reduced health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons in Germany. Thereby, the relationship between the depressed person and the co-living household members seemed to be important for the health-related quality of life of the co-living household members. It is known that a stable and continuous social relationship with a close person can positively influence the course of a depression (Leach et al., 2008). A better health-related quality of life of co-living household members can therefore be expected to positively influence the course of depression and thus probably also the health-related quality of life of the depressed person. Furthermore, according to the results of the current study, it is likely that a better health-related quality of life of depressed persons also positively influences the health-related quality of life of co-living household members.

The health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons might thus be positively influenced by an adequate pharmacological and psychological treatment of the depression. An improvement in symptoms could lead to less stress in the social environment, which in turn could positively influence the health-related quality of life of the co-living household members. Since the onset and success of a therapy depends essentially on the person’s awareness of being ill, which is often late in the case of depression (Stegenga et al., 2012), the current study was able to show a reduced health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons even before the actual diagnosis. As health-related quality of life reflects the subjective perception of health aspects, it is likely that co-living household members of depressed persons perceive behavioral changes in the depressed person even before the actual diagnosis. Therefore, psychological and social counselling for co-living household members of depressed persons should be established to support in dealing with such a situation in advance. However, further research is needed to confirm these findings internationally. This is particularly important as health-related quality of life is known to be country-specific due to cultural differences.

Strength and limitations

In contrast to data from published studies, the German Socio-Economic Panel allows determining the health-related quality of life in the social environment of depressed persons. Thus, a large sample of households with depressed persons (n = 1058) and households without depressed persons (n = 11,985) was analyzed longitudinally in the current study. In addition, missing values were imputed by advanced statistical methods using multiple imputation by chained equations to avoid a loss of statistical power. Furthermore, skewness in health-related quality of life data was taken into account by using beta regression.

Although the health-related quality of life of co-living household members and depressed persons was statistically significantly correlated and changed similarly over time, depression may not be the only reason for the reduced health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons. In addition, confounding factors (e.g. loss of income due to unemployment) may also have influenced health-related quality of life negatively. Thereby, confounding factors can also lead to depression. However, this may not be the case for every person, making it difficult to determine the influence of these confounding factors on health-related quality of life. Furthermore, it might be possible that missing information on the diagnosis of depression influenced the results. Thereby, the depression diagnosis was self-reported and therefore did not necessarily correspond to a medical diagnosis. Self-reported diagnosis often leads to a recall bias, which in turn might have influenced the representativeness of the sample. Furthermore, information on clinical parameters such as the severity of depression or depression treatment was missing. By limiting the observation period to 4 years before and 2 years after diagnosis, an attempt was made to map the symptomatic phase of depression. However, clinical parameters would have been particularly important to verify treatment effects. Furthermore, long-term analyses could be conducted, which are currently not yet possible. Therefore, results were only explanatory and should be regarded as preliminary.

Conclusions

Overall, in the representative sample of German households of the Socio Economic Panel, the health-related quality of life of co-living household members of depressed persons was reduced. The health-related quality of life of female co-living household members was more reduced than the health-related quality of life of males. It is therefore important to address the support of co-living household members of depressed persons besides merely the treatment of depression of the person affected.

Data Availability

The data can be applied for via the website of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), Berlin. It is available for scientific, uncommercial use for researchers free of charge.

References

Albert, P. R. (2015). Why is depression more prevalent in women? Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience : JPN, 40(4), 219–221. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.150205

Andersen, H. H., Mühlbacher, A., & Nübling, M. (2007). Die SOEP-Version des SF 12 als Instrument gesundheitsökonomischer Analysen.

Bechmann, S., & Sleik, K. (2016). SOEP-LEE Betriebsbefragung – Methodenbericht der Betriebsbefragung des Sozio-oekonomischen Panels. In J. Goeble, M. Kroh, C. Schröder, & J. Schupp (Eds.). Berlin: DIW Berlin.

Bohlender, A., Huber, S., Glemser, A., (Kantar Public). (2018). SOEP-Core – 2016: Methodenbericht Stichproben A-L1 SOEP Survey Papers 493 (Vol Series B). Berlin: DIW/SOEP.

Brazier, J. E., & Roberts, J. (2004). The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Medical Care, 42(9), 851–859. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000135827.18610.0d

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.: DSM-V. (2013). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Gagliese, L., Gauthier, L. R., & Rodin, G. (2007). Cancer pain and depression: A systematic review of age-related patterns. Pain Research & Management, 12(3), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1155/2007/150126

Gold, S. M., Köhler-Forsberg, O., Moss-Morris, R., Mehnert, A., Miranda, J. J., Bullinger, M., et al. (2020). Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 6(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0200-2

Hammen, C., Brennan, P. A., & Shih, J. H. (2004). Family discord and stress predictors of depression and other disorders in adolescent children of depressed and nondepressed women. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(8), 994–1002. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000127588.57468.f6

Hammen, C., Shih, J., Altman, T., & Brennan, P. A. (2003). Interpersonal impairment and the prediction of depressive symptoms in adolescent children of depressed and nondepressed mothers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(5), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000046829.95464.e5

Hawton, K., Casañas, I. C. C., Haw, C., & Saunders, K. (2013). Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1–3), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

Jääskeläinen, E., Juola, T., Korpela, H., Lehtiniemi, H., Nietola, M., Korkeila, J., et al. (2018). Epidemiology of psychotic depression - systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 48(6), 905–918. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717002501

Kamenov, K., Twomey, C., Cabello, M., Prina, A. M., & Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. (2017). The efficacy of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and their combination on functioning and quality of life in depression: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(3), 414–425. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002774

Kessler, R. C., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Wittchen, H.-U. (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1359

Leach, L. S., Christensen, H., Mackinnon, A. J., Windsor, T. D., & Butterworth, P. (2008). Gender differences in depression and anxiety across the adult lifespan: The role of psychosocial mediators. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(12), 983–998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0388-z

Meléndez, J. C., Mayordomo, T., Sancho, P., & Tomás, J. M. (2012). Coping strategies: Gender differences and development throughout life span. Span J Psychol, 15(3), 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n3.39399

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2010). Depression: The treatment and management of depression in adults - national clinical pracitice guideline 90. The British Psychological Society & The Royal College of Psychiatrists.

National Health Service (2018). How to help someone with depression. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/advice-for-life-situations-and-events/how-to-help-someone-with-depression/. Accessed 26th July 2021.

Nübling, M., H. Andersen, H., & Mühlbacher, A. (2006). Entwicklung eines Verfahrens zur Berechnung der Körperlichen und psychischen Summenskalen auf Basis der SOEP-Version des SF 12 (Algorithmus).

Parker, G., & Brotchie, H. (2010). Gender differences in depression. International Review of Psychiatry, 22(5), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.492391

Picco, L., Subramaniam, M., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J. A., & Chong, S. A. (2017). Gender differences in major depressive disorder: findings from the Singapore Mental Health Study. Singapore Medical Journal, 58(11), 649–655. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2016144

Richards, D. (2011). Prevalence and clinical course of depression: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1117–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.004

Rubio, L., Dumitrache, C., Cordon-Pozo, E., & Rubio-Herrera, R. (2016). Coping: Impact of Gender and Stressful Life Events in Middle and in Old Age. Clinical Gerontologist, 39(5), 468–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2015.1132290

Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S., & Abramson, L. Y. (2017). Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychological Bulletin, 143(8), 783–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000102

Scerri, J., Saliba, T., Saliba, G., Scerri, C. A., & Camilleri, L. (2019). Illness perceptions, depression and anxiety in informal carers of persons with depression: A cross-sectional survey. Quality of Life Research, 28(2), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2009-y

Schupp, J., Wagner, G., Nübling, M., H. Andersen, H., & Mühlbacher, A. (2007). Computation of Standard Values for Physical and Mental Health Scale Scores Using the SOEP Version of SF12v2 (Vol. 127).

Seritan, A. L., Rienas, C., Duong, T., Delucchi, K., & Ostrem, J. L. (2019). Ages at Onset of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 31(4), 346–352. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.18090201

Sheeber, L., Hops, H., Andrews, J., Alpert, T., & Davis, B. (1998). Interactional processes in families with depressed and non-depressed adolescents: Reinforcement of depressive behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(4), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10030-4

Steffen, A., Nübel, J., Jacobi, F., Bätzing, J., & Holstiege, J. (2020). Mental and somatic comorbidity of depression: A comprehensive cross-sectional analysis of 202 diagnosis groups using German nationwide ambulatory claims data. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02546-8

Stegenga, B. T., Kamphuis, M. H., King, M., Nazareth, I., & Geerlings, M. I. (2012). The natural course and outcome of major depressive disorder in primary care: The PREDICT-NL study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0317-9

van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–67.

Ware, J., Jr., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233.

Word Health Organisation. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. WHO.

Yaribeygi, H., Panahi, Y., Sahraei, H., Johnston, T. P., & Sahebkar, A. (2017). The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI Journal, 16, 1057–1072. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2017-480

Acknowledgements

The data used in this study was made available by the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), Berlin.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD made substantial contributions to the conception and the design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. TG and HHK made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was a secondary analysis of anonymized data, and therefore an ethics approval was not required. Participants gave their informed consent prior to data collection. Detailed information on ethical clearance and informed consent given by the participants related to the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) can be found on the website of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), Berlin (https://www.diw.de/soep).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dams, J., Grochtdreis, T. & König, HH. Health-Related Quality of Life of Individuals Living In Households with Depression: Evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). Applied Research Quality Life 17, 2087–2100 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-10023-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-10023-x