Abstract

This study examined the impact of household assets on multiple dimensions of child well-being using data on 2,583 children aged 10–15 years and their families from the cross-sectional 2016 China Family Panel Studies survey. Household assets were measured as the value of housing assets, cash deposits and household durable goods. Child well-being was measured with 10 indicators in five dimensions: health, education, economic well-being, subjective well-being and family relationships. Multiple linear regression was applied to investigate whether household assets were predictive of child well-being. The results suggest that children living in households with relatively low levels of household assets have lower overall well-being than those living in families with higher levels of assets. The impacts of diverse household asset types on various aspects of children’s well-being are different. Additionally, the relationship between household assets and various dimensions of child well-being is different and unequal between rural and urban areas, as well as among the eastern, central, and western regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children are the future of society and are important resources for sustainable development. Therefore, facilitating their development and improving their level of well-being have become the focal points of the child policies of all governments. Among the numerous factors affecting child well-being and development, household economic factors have always been a focus of attention among scholars and policy-making authorities. As it is relatively easy to access data on income and wages, early studies focused on the impacts of income distribution and inequality on children. Many of these studies (Duncan et al., 1994, 1998; Nicholas et al., 1995; Parker et al., 1989) showed that income inequality had been intensifying in recent years, which has threatened the well-being of children. All these empirical studies found that children from low-income families exhibited lower levels of academic achievement, worse health conditions, and increased behavioral problems. Some researchers have explored the impacts of socioeconomic factors on children from a much broader perspective, such as by considering the impacts of economic pressure on childcare and child outcomes (Conger et al., 1994).

In the past few decades, researchers in Western developed countries, through large-scale nationwide surveys, have estimated residents’ financial situations, especially as relates to their assets, and have built more mature questionnaire systems and databases. These databases have provided reliable and rich data that have supported studies of household assets (Deng et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2015, 2017). In the twenty-first century, the role of asset-based child policies in the transformation of social investment-oriented welfare nations has drawn increasing attention. The asset building policy is different from the traditional income support policy and it focuses on the long-term social development towards life course, instead of the short-term need of remedial welfare (Sherraden, 1991). Due to its particular attention to poverty’s impact on child development, asset building has attracted much attention of researchers on child well-being policies and practices in this field, such as Child Development Account (CDA), which has been carried out in many countries and regions. Some countries, such as Canada, Singapore, and the United Kingdom, have formulated child welfare policies based on asset building, which have been proven to have achieved good results by related studies.

The introduction of assets into child welfare policy is an innovative theoretical development. Unlike income, assets are a stable aggregation of resources and an important foundation for individuals and households to obtain economic security as well as develop socially (Sherraden, 1991). Assets are also a dynamic concept. Asset building is not meant to entirely satisfy present welfare or consumption needs but rather focuses on providing opportunities to individuals and households for their long-term development; in particular, asset building helps to break the poverty cycle of low-income households (Sherraden, 1991). This is also a process of capacity building. Empirical studies investigating the relationship between assets and child development outcomes have suggested that assets have positive influences on children’s capability in different aspects (Grinstein-Weiss et al., 2014). These findings lend support to the validity of asset-based welfare policies.

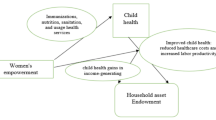

In addition, researchers of asset building noticed that early asset accumulation generates greater welfare effects for individuals or families and better prevents multiple risks in one’s life (Sherraden, 1991). Based on empirical studies, we can determine that family asset holding has a positive impact on various indicators of children’s development, including their educational attainment, health, and self-efficacy. Previous research results have strongly indicated that the influence of assets on children’s wellbeing is mainly achieved through the following channels.

First, an important mechanism underlying the effects of asset building may be that it protects the families first, which ensures the sustainability of children’s wellbeing. The building up of household assets, especially liquid assets, can save them from financial crises and reduce the negative outcomes of such crises. For example, a financial crisis may make it difficult for families to pay rent, thus forcing them to leave their houses under great duress. In addition, even a small crisis can lead to a sharp decline in family living standards and further damage the children’s wellbeing either directly or by reducing the quality of the parent–child interactions. Children in families with assets are more likely to be protected from the most severe consequences of financial crises (Grinstein-Weiss et al., 2009).

Second, the act of building up assets may reduce parental stress and improve child mental health. In addition to alleviating family hardships, asset building also relieves the life pressures on parents. For instance, with enough household savings, parents no longer need to worry about paying bills, so they can become fully involved in their family life and take better care of their children. By contrast, increased stress can induce marital conflicts, reduce marital affection and reduce parenting time, further leading to poor cognitive abilities, social skills, health conditions and academic performance for the children (Grinstein-Weiss et al., 2009). Additionally, Grinstein-Weiss et al, (2009) believes that assets provide a sense of security and reduce the impact of parental stress, thus increasing the possibility of positive family interactions.

Third, asset building may help parents invest in child education to improve child academic performance. The more parents invest in education, the greater the chance their children may have to develop. Parental financial status is an important factor that influences child success in education. The building of assets, as one of the key channels for financial resource accumulation, plays a significant role in child educational achievements. Parents decide whether to have a child as well as the number of children to have through a cost–benefit analysis (Haveman & Wolfe, 1994). A great deal of the existing research has confirmed the positive correlation between family assets and child academic performance, as well as the length of the child’s education. Additionally, research has shown that asset building can improve children’s developmental opportunities because of parents’ higher expectations (Grinstein-Weiss et al., 2014).

The process of household asset accumulation not only alters parental nurturing behaviors, parental characteristics, and the household environment but also provides a household background that supports child development (Sherraden, 1991). Related studies have investigated the impacts of assets on children, emphasizing that household assets can not only provide for the most basic needs for children but can also improve their well-being in several respects, such as enhancing their academic achievements (Elliott & Beverly, 2011; Friedline et al., 2015), improving their physical health (Coravalan et al., 2005; Gwatkin et al., 2000; Hong, 2007), lowering school absence rates (Filmer & Pritchett, 2001; Kim et al., 2017; Leventhal & Newman, 2010), and increasing self-esteem (Barker & Miller, 2009; Graham-Bermann et al., 1996; Leventhal & Newman, 2010). Children living in asset-rich households have better economic, social, and mental health outcomes. By comparison, children living in poor families are more likely to suffer negative consequences related to their poverty (Li et al., 2017; Mckernan et al., 2009). Children of wealthy households are well protected from economic difficulties and have better access to education and health resources. In the long run, household assets also contribute to the social mobility of children and have positive psychological and social impacts on their sense of self-efficacy, future orientation and civic behavior (Pfeffer & Hällsten, 2012).

Moreover, child well-being is a very broad concept that is subject to the influences of many factors, such as economic conditions, political rights, family relations and opportunities for development (Lippman et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2020a, b, c; Zhou et al., 2020a, b, c). Therefore, indicators for measuring child well-being must touch on many dimensions. In recent years, almost all the measurement studies and evaluation reports in terms of child well-being have used the framework of the Convention on the Rights of the Child as an example of a specific indicator framework for evaluating child well-being (Bradshaw et al., 2007; Mclanahan, 2000; OECD, 2017; UNICEF, 2019). All these studies have demonstrated that the use of well-structured, relevant, effective, reliable, powerful, and useful indicators has become an accepted method for measuring and monitoring child well-being. In this respect, the combination of objective and subjective indicators is also very important. Objective well-being refers to living conditions that can be ascertained, which are usually generalized as material well-being, health conditions, and social relations, while subjective well-being involves mental health, socialization ability, etc. Although existing studies have demonstrated the importance of household assets in child development, previous studies on their impacts have mostly focused on a single dimension and have failed to discuss their impacts within the overall framework of child well-being. Sharing the same concern, these studies are also dominated by Western researchers and theorists (Leung & Fung, 2021; Qi et al., 2020).

To address the above-mentioned research gaps, this study used data from the China Family Panel Studies to examine the relationship between household assets and child well-being in the context of Chinese society. In this study, we divided household assets into cash, bank savings, housing assets, and consumer durables, and conducted a correlation analysis with the specific indicators of child well-being. The present study aims to examine the relationship between household assets and child well-being along multiple dimensions, which leads to the following hypotheses:

-

H1: Household assets could predict children’s health.

-

H2: Household assets could predict children’s academic achievement.

-

H3: Household assets could predict family relations.

-

H4: Household assets could predict children’s economic well-being.

-

H5: Household assets could predict children’s subjective well-being.

Measures

Data and Sample

Currently, there is no nationwide survey specifically covering child and adolescent development in China. Child well-being is mainly researched through large-scale family-based surveys, comprehensive health surveys, or education-tracking surveys. After comparing the time range and representativeness of various surveys that provide open data for all the researchers, data from the 2016 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) was selected. The dataset was obtained from the Social Research Center of Peking University and downloaded from its Internet-based data center (http://opendata.pku.edu.cn/). Conducted by Peking University’s Institute of Social Science Surveys, the CFPS is a nationally representative and longitudinal survey of households in China. The survey aims to obtain panel data at the individual, family, and community levels to capture social and economic transformations in China and to provide primary empirical data for research and political decision-making. In developing its questionnaire, the CFPS has learned from the experiences of several well-known surveys in other countries (e.g., the PSID, CDS, HRS, NLSY) and includes many sections, such as family economic well-being, consumption, income, and assets. This survey includes 14,798 households from 635 villages (communities) located in 162 counties in 25 provinces (or centrally administered municipalities and autonomous regions). Stratified multistage sampling enables the survey sample to represent approximately 95% of the Chinese population (Xie & Lu, 2015). Meanwhile, the questionnaires for the CFPS are mainly of four types: a community questionnaire, family questionnaire, adult questionnaire and child questionnaire (for children 10–15 years old). The present study conducted additional data cleaning on the family questionnaire and child questionnaire (10–15 years old). The selected data include the main characteristics of family members and the status of household assets and can support the study of the relationship between household assets and the welfare of children. The final sample consisted of 2,583 children from 10–15 years old.

Independent Variables

Assets have different forms and can be measured in many ways. Researchers sometimes only examine asset ownership, but if the data allow, they consider asset values (Grinstein-Weiss et al., 2014). To measure the total value of household assets, researchers often combine the value of financial assets (for example, shares in bank accounts, pensions and funds) and that of tangible nonfinancial assets (such as housing, businesses and vehicles). Net asset value is an evaluation of assets and liabilities, which is usually measured as the value of assets less liabilities. Further, to increase the feasibility of the research design, some studies have employed a much narrower measure of current assets, namely, assets that can be quickly converted into cash (Grinstein-Weiss et al., 2014). In this paper, we considered total household assets as an independent variable, including cash, bank savings, and the value of housing property and consumer durables. The specific question for cash was “What is the total amount of cash and bank savings currently held by all your household members?” The question for durables was “What is the total value of consumer durables (except rented or borrowed durable goods) currently owned by your household, such as cars, computers, household appliances, jewelry, antiques, and expensive musical instruments (such as pianos)?” The question for housing assets was “What is the market value of your house?”. In the present study, the details of all variables are shown in Table 1.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variable in this study was child well-being. In general, the existing literature distinguishes four to six dimensions of child well-being: health, education, economic well-being, risk, family and peer relationships, and subjective well-being (Bradshaw & Richardson, 2009; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Lindsey, 1995; Lindsey & Shlonsky, 2008; McGowen & Lindsey, 1995). We identified 5 dimensions for child well-being: health, education, family relations, economic well-being, and subjective well-being. There were two indicators in the health dimension, including children’s self-assessment of their health and weekly exercise frequency. The education dimension included educational outcomes as measured by the children’s Chinese and math scores. For the family relationship dimension, parents’ concern for their children’s education and parents’ communication with their children were selected. The economic well-being indicators included education expenditure in the past 12 months and whether the children have pocket money. The indicators for subjective well-being were self-esteem and happiness (see Table 1).

Control Variables

The analyses were adjusted for multiple control variables, including demographics and income. Demographic control variables included the child's gender (male = 1, female = 0), age in 2016, location of registered permanent residence (1 = urban area and 0 = rural area or no registered permanent residence), the family’s current region of residence (1 = Eastern region, 2 = Central region and 3 = Western region), and annual family income (family income is the sum of earnings from all family members in the past twelve months). To solve problems due to skewed distributions, we took the log-transformation of family annual income and assets; for families with zero income or savings, their log-transformed variables were defined as 0.

Analyses

To examine the relationship between household assets as a whole and household asset of different types and child well-being, household assets were divided into housing assets, cash deposits, and durable goods, and statistical analysis was conducted with multiple dimensions of child well-being. First, we conducted a descriptive statistical analysis to show the basic conditions of child well-being and household assets. Second, we conducted a zero-order correlation analysis to examine the binary correlations between the variables. Finally, after controlling for socioeconomic status, we conducted a regression analysis using child well-being indicators of different dimensions as dependent variables and household assets as independent variables. In addition, we also focused on the impact of household assets on child well-being under different economic and regional conditions. First, to analyze the differences between urban and rural areas, we divided the sample and analyzed the two areas separately, using household assets to predict the indicators of child well-being as before. Second, to study the differences in asset effects across different regions, the provincial- and regional-level areas were divided into three regions based on location: the eastern, central, and western regions; the asset effects were analyzed and compared among these three regions. The regional division in the sample is based on the statistical data from the fourth national economic census of the National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables in this study. The total number of children was 2,583, including 1,391 males (53.9% of the total) and 1,192 females (46.1% of the total). In terms of the age distribution in the sample, 17% of children were aged 10, 18.7% of children were aged 11, 18.7% of children were aged 12, 14.3% of children were aged 13, 16.6% of children were aged 14 and 14.7% of children were aged 15. In addition, 1,525 children were from rural areas, accounting for 59.0% of the total, and 1,035 were from urban areas, constituting 40.1% of the total; household registration information for 23 children was missing (0.9%). In terms of the regional distribution, the sample included 845 children from the eastern region, accounting for 32.7% of the sample, 797 children from the central region, making up 30.9%, and 941 children from the western region, accounting for 36.4%.

For the independent variables, the proportion of households with cash and bank savings between 0 and 3 million (RMB) in the sample was 95.8%, and the percentage of observations with missing data was 4.2%. The average value of cash and deposits was 37,844 RMB with a median value of 5,000 RMB. The proportion of households with durable goods valued from 0 to 10,000 RMB was 98.1%, and the percentage with missing values was 1.9%. The average value of durable goods was 35,905 RMB, and the median was 10,000 RMB. The percentage of households with housing assets valued between 10 thousand and 10 million (RMB) was 99.1%, and the percentage with missing values was 0.9%. The average value of housing assets was 403,789 RMB, and the median was 160,000 RMB.

The descriptive results for the dependent variables are also shown in Table 2. For the health variables, the children exercised between 2 and 3 times in the past week, and the average level of children’s self-assessed health was between “comparatively healthy” and “generally healthy”. For the education variables, the average scores for both Chinese and math were between “good” and “fair”. For the family relationships variables, children on average were between agreement and neutrality with respect to having active communication with their parents and their parents caring about their education. Regarding subjective well-being, the average self-esteem score of children was 3.85, and the average happiness score was 8.27. For economic well-being, 98.4% of the children had received investments in education and training from their families, and only 1.6% of households did not spend on education and training for their children. The average family expenditure on education and training for children was 5,900 RMB, with a median expenditure of 3,000 RMB. The children who received pocket money accounted for only 73.4% of the total, and those who did not receive pocket money accounted for 26.6%. The average amount of pocket money for children was 78 RMB, and the median was 40 RMB. Table 3 shows the correlations between the variables.

Household Assets and Child Well-Being

To further investigate the various impacts of household assets on child well-being, ten indicators of child well-being were treated as dependent variables, while total household assets and three different types of assets were treated as independent variables in a multiple regression analysis that controlled for gender, age, urban and rural status, and total household income. The results of the multiple linear regression model showed that correlations existed between different types of household assets and different dimensions of child well-being (Table 4). First, total household assets positively predicted two indicators: parents’ concern for their children’s education (β = 0.071, R2 = 0.023, p < 0.01) and education expenditure (β = 0.099, R2 = 0.038, p < 0.001). Therefore, the relationship between total household assets and two of the dimensions of child well-being, children’s family relations and economic well-being, is relatively close. Of the three different types of assets, cash and bank savings had the highest correlation with the various dimension of child well-being, including the three dimensions of health, education, and economic well-being. Specifically, cash and bank savings significantly predicted children’s exercise frequency (β = 0.047, R2 = 0.036, p < 0.05), language performance (β = 0.044, R2 = 0.040, p < 0.05), mathematics performance (β = 0.078, R2 = 0.041, p < 0.001), perception of their parents’ attitude towards their education (β = 0.080, R2 = 0.024, p < 0.001), and self-esteem (β = 0.072, R2 = 0.038, p < 0.05), as well as parents’ education expenditure (β = 0.133, R2 = 0.046, p < 0.001). In addition, consumer durables and children’s exercise frequency were positively correlated (β = 0.069, R2 = 0.040, p < 0.01). Second, housing assets and consumer durables had no significant predictive effect in relation to children’s academic achievements (p > 0.05). Housing assets (β = 0.064, R2 = 0.022, p < 0.005) and consumer durables were positively correlated(β = 0.067, R2 = 0.022, p < 0.005) with parents’ concern for their children’s education. Further, housing assets(β = 0.081, R2 = 0.037, p < 0.001) and consumer durables (β = 0.196, R2 = 0.062, p < 0.001) could also positively predict expenditure on children’s education. In other words, households with higher value housing assets and consumer durables tend to pay greater attention to their children’s education and spend more on it. However, there was no significant correlation between total household assets (nor the three types of household assets) and children’s self-assessment of their health, their happiness, or their pocket money.

Table 5 shows the correlative relationship between household assets and children of different genders. From the results of the regression analysis for boys, when the controls for age and total household income were included, total household assets positively predicted their parents’ concern for their education (β = 0.070, R2 = 0.021, p < 0.05) and their parent’s expenditure on their education (β = 0.155, R2 = 0.031, p < 0.001). For girls, total household assets were positively correlated with their parents’ concern for their education (β = 0.078, R2 = 0.025, p < 0.05)and their parents’ education expenditure (β = 0.071, R2 = 0.066, p < 0.05). Second, of the three types of assets, cash and bank savings positively predicted four indicators, namely, boys’ mathematics performance (β = 0.083, R2 = 0.041, p < 0.005), their parents’ concern for their education (β = 0.112, R2 = 0.028, p < 0.001), their parents’ communication level (β = 0.081, R2 = 0.024, p < 0.05), and their parents’ education expenditure (β = 0.186, R2 = 0.042, p < 0.001), while these assets had a positive correlation with girls’ mathematics performance only (β = 0.073, R2 = 0.038, p < 0.05). Next, housing assets positively predicted parents’ concern for their children’s education (β = 0.076, R2 = 0.022, p < 0.05) and parents’ education expenditure among families with daughters (β = 0.065, R2 = 0.023, p < 0.05). In families with sons, housing assets were positively correlation with education expenditure only (β = 0.123, R2 = 0.040, p < 0.001). Finally, for families with sons, consumer durables positively predicted the children’s exercise frequency (β = 0.072, R2 = 0.040, p < 0.05), the parents’ concern for their children’s education (β = 0.091, R2 = 0.025, p < 0.01), and the parents’ education expenditure (β = 0.180, R2 = 0.037, p < 0.001), while such durables were significantly correlated only with child exercise frequency (β = 0.065, R2 = 0.022, p < 0.05) and parental education expenditure in families with daughters (β = 0.223, R2 = 0.105, p < 0.001).

Table 6 shows the results of the correlative relationship between household assets and children’s well-being for those with urban and rural registration status. When the controls for age and total household income were included, total household assets positively predicted rural children’s happiness (β = 0.089, R2 = 0.021, p < 0.05) and pocket money (β = 0.088, R2 = 0.092, p < 0.01), but a significantly negative correlation existed between such assets and rural children’s language performance (β = -0.058, R2 = 0.031, P < 0.05). For urban children, total household assets and two indicators, parents’ concern for their children’s education (β = 0.107, R2 = 0.009, p < 0.01) and parents’ education expenditure (β = 0.134, R2 = 0.043, p < 0.001), had a positive correlation. Among the three types of assets, cash and bank savings positively predicted rural children’s health self-assessment (β = 0.073, R2 = 0.007, p < 0.01), mathematics performance (β = 0.101, R2 = 0.023, p < 0.001), and happiness (β = 0.094, R2 = 0.020, p < 0.05). At the same time, both cash and bank savings positively predicted urban children’s exercise frequency (β = 0.067, R2 = 0.015, p < 0.05) and mathematics performance (β = 0.083, R2 = 0.028, p < 0.05), and their parents’ concern for their education (β = 0.108, R2 = 0.009, p < 0.01) and education expenditure (β = 0.181, R2 = 0.056, p < 0.001). Housing assets and rural children’s happiness (β = 0.090, R2 = 0.021, p < 0.05) and pocket money (β = 0.110, R2 = 0.099, p < 0.001) were significantly positively correlated, but there was a significant negative correlation between housing assets language (β = -0.058, R2 = 0.031, p < 0.05) and mathematics performances of children (β = -0.060, R2 = 0.016, p < 0.05). At the same time, housing assets positively predicted two indicators: parental education expenditure for urban children (β = 0.110, R2 = 0.040, p < 0.001) and their parents’ concern for their education (β = 0.099, R2 = 0.008, p < 0.01). Further, consumer durables positively predicted education expenditure among parents of rural (β = 0.082, R2 = 0.016, p < 0.01) and urban (β = 0.265, R2 = 0.088, p < 0.001) children and the exercise frequency of urban children (β = 0.085, R2 = 0.017, p < 0.05).

Table 7 shows the correlative relationships between housing assets and children’s well-being in different regions. When the controls for gender, age, and household income were included, total household assets were significantly positively correlated with parental education expenditure (β = 0.109, R2 = 0.039, p < 0.01) and parental concern for their children’s education (β = 0.093, R2 = 0.021, p < 0.05) in the eastern region. At the same time, total household assets had a significantly positive relationship with the exercise frequency (β = 0.144, R2 = 0.070, p < 0.001) and mathematics performance (β = 0.083, R2 = 0.028, p < 0.05) and parental education expenditure on children (β = 0.167, R2 = 0.052, p < 0.001) in the central region. Further, total household assets significantly predicted the self-esteem of children (β = -0.124, R2 = 0.026, p < 0.05) in the western region. Second, in the eastern region, cash and bank savings were positively correlated with children’s exercise frequency (β = 0.081, R2 = 0.034, p < 0.05) and mathematics performance (β = 0.078, R2 = 0.030, p < 0.05), their parents concern for their education (β = 0.143, R2 = 0.029, p < 0.001), their self-esteem (β = 0.120, R2 = 0.060, p < 0.05), and their parents’ education expenditure (β = 0.111, R2 = 0.040, p < 0.01), but there was a significantly positive correlation only with parental education expenditure in the central region (β = 0.255, R2 = 0.091, p < 0.001) and only with children’s mathematics performance (β = 0.121, R2 = 0.052, p < 0.01) in the western region. However, cash and bank savings’ correlation with two indicators—parent–child communication (β = -0.107, R2 = 0.023, p < 0.05) and children’s self-esteem—was significantly negative (β = -0.060, R2 = 0.021, p < 0.05). Housing assets had a significant positive correlation with parental concern for their children’s education (β = 0.084, R2 = 0.020, p < 0.05) and parental expenditure on their children’s education (β = 0.091, R2 = 0.037, p < 0.05) in the eastern region, with the exercise frequency of (β = 0.144, R2 = 0.069, p < 0.001) and parental education expenditure on children (β = 0.137, R2 = 0.043, p < 0.001) in the central region, and with the pocket money of children (β = 0.142, R2 = 0.084, p < 0.001) in the western region; however, housing assets had a significant negative correlation with children’s self-esteem (β = -0.111, R2 = 0.021, p < 0.05). Consumer durables positively predicted parental expenditure on children’s education in all three regions. In addition, such durables had a significant positive correlation with the exercise frequency of children (β = 0.078, R2 = 0.026, p < 0.05) in the eastern region and with the language performance of children (β = 0.073, R2 = 0.045, p < 0.05) and their parents’ concern for their education (β = 0.104, R2 = 0.031, p < 0.01) in the western region.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between household assets and child well-being. We analyzed the relationship between three types of household assets (including cash deposits, housing assets and durable goods) and child well-being. There were several key findings. First, our research results showed that children living in households with relatively lower household asset values had worse overall welfare than children living in families with higher asset values. More importantly, we found that various household asset types have different effects on diverse aspects of children’s well-being. Specifically, families with a higher total value of current assets (cash, bank savings) and durable goods have children who exercise more frequently, implying that children’s health is also higher. However, we did not find a correlation between household assets and children’s self-rated health status. Regarding children’s education and welfare, current assets in the family are significantly related to children’s academic achievements, and children in families with higher cash deposits also have better academic performance than those in families with lower deposits. Previous studies have usually focused on the impact of assets on children’s educational achievements along two dimensions: academic performance and years of education (Loke & Sherraden, 2009; Orr, 2003). This study indicates that different assets will have different effects on education, and the same assets may also have different effects on different academic achievements.

In addition, household assets were found to positively affect parents’ concern about their children’s education. The higher the total family cash, bank savings, and total value of housing assets and consumer durables, the more family attention was given to the children’s education. Previous studies have found that assets serve as a tunnel for parents to transfer resources to their children (Zhan & Sherraden, 2003, 2011). When families have more assets, parents have higher expectations for their children (Kim et al., 2015). Therefore, the findings in the present study are in line with the findings of previous research. It could be inferred that parents with higher assets are more concerned about and involved in their children’s educational behaviors. In addition, due to the close relationship between economic well-being and household assets, there is also a clear correlation between different types of household assets and education expenditure. We found that families with more current assets (cash, bank savings), housing assets, and consumer durables also have relatively higher expenditure on their children’s education.

Second, boys are more sensitive to different types of assets than girls. For boys, families with more cash deposits and durable goods have better performance along different welfare dimensions, in particular, parental interest in their children's education and parental education expenditure. In addition, for children living in rural areas, there was no obvious correlation between household assets and child well-being. Children living in urban areas were more likely to be affected family assets. There have been many discussions about the differences in child well-being between urban and rural areas in China (Guo et al., 2016; Knight & Gunatilaka, 2008; Lu et al., 2019; Xu & Xie, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). However, few of them have consider the influence of assets. Although this study provided some evidence on urban–rural differences, data limitations exist, and more empirical data are needed to further explore the reasons behind these differences.

The third major finding of this study is that there were differences in the impact of different household asset types on children living in eastern, central, and western China. The welfare of children living in eastern China was most closely related to household fixed assets, then to current assets, and finally to durable goods. Of these, the current assets in the family, namely, the value of cash and bank savings, have different degrees of correlation with the various dimensions of child well-being. The results on the relationship between child well-being and household assets in central China showed that, apart from physical health and direct expenditure on education, household assets were not significantly related with child well-being. Finally, child well-being and household assets are also relatively closely related in the western region, but this differs from the results for children living in the eastern region. Specifically, the higher the total value of household durable goods is, the higher the level of parents’ interest in their children’s education among households in the western region, while the level of parental interest in children’s education among households in the eastern region was only related to the total value of household current assets and fixed assets. This result also indicates that household assets in more developed regions have a stronger impact on child well-being (Guo et al., 2016; Xu & Xie, 2015; Zhang et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2020a, b, c).

Recently, the intergenerational transmission of poverty in China’s urban and rural areas has attracted increasing attention. There is a growing trend towards the intergenerational transmission of poverty in rural areas that is related to education, wealth and employment (Chen et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020). The development of children in poor rural families has been emphasized in studies on the intergenerational transmission of poverty. Compared with urban children of the same age, left-behind and disadvantaged rural children lack better educational and occupational opportunities. Moreover, parent–child separation and community risk factors may also lead to poverty, crime and physical and mental problems in adulthood. Although the policies issued by the Chinese government in recent years have lifted many rural families out of poverty, there is still a large gap between poverty alleviation policies and child welfare policies. The relevant policies, such as subsidies for the most disadvantaged children, medical assistance for children in need, as well as care and protection services for left-behind children, are still relatively incomplete and do not form a complete welfare system. Children’s problems to a large extent reflect problems in family development; from this perspective, future child policies should include integrated poverty alleviation interventions directed towards the development of both children and families so as to better address the intergenerational transmission of poverty and enhance the sustainability of anti-poverty measures. Certainly, we can draw lessons from asset building theories to further improve our current anti-poverty policies and service systems.

Asset accumulation can help children avoid life risks, attain a positive future orientation and obtain better developmental opportunities. A typical application of asset building in child wellbeing policies is a project called the “Child Development Account (CDA)”, which has been implemented in many countries and regions. Its applications have also provided practical references for the design of child wellbeing projects in China. However, the way in which assets are built up may vary in different places because of those place’s different social systems and cultural backgrounds. For example, CDAs in areas such as Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan (Cheng, 2019; Han & Chia, 2012), which are largely affected by Chinese culture, reveal that families and peers play a positive role in maintaining the project. Here, CDAs are not just an intervention for children but an effective channel for the better development of the whole family. In this sense, this project provides not only a policy tool to promote asset savings but also a model of an intergenerational poverty intervention that is culturally sensitive and development oriented. In summary, we found that children from families with assets have better outcomes than those from families without assets. There is also reason to expect that asset-building projects can increase family assets and then improve child outcomes. Long-term asset building projects, especially early, universal and progressive projects, seem to be the most likely to improve the wellbeing of children in low-income families.

However, this study still has limitations. First, since the present study only used cross-sectional data, the longitudinal impact of household assets on children’s development was not directly examined. Future studies could incorporate longitudinal data into the analysis to further verify the relationship between household assets and child development. Second, due to data limitations, the classification of asset types was limited. Third, the effect sizes of the main effects are low, and we should be cautious to avoid over interpretation of the findings. In addition, the mechanism underlying the relationship between family assets and child well-being was not investigated in the present study. Family assets should have effects on parental psychology and wellbeing (Shek, 2008)), and previous research has suggested that family processes such as parenting styles and attributes are related to child wellbeing (Dou et al., 2020; Shek, 1995). Future studies can further examine the mediating factors that contribute to the link between household assets and child wellbeing.

References

Barker, D., & Miller, E. (2009). Homeownership and Child Welfare. Real Estate Economics, 37(2), 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6229.2009.00243.x

Bradshaw, J., Richardson, D., & Ritakallio, V. (2007). Child poverty and child well-being in europe. Journal of Childrens Services, 2(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/17466660200700003

Bradshaw, J., & Richardson, D. (2009). An Index of Child Well-Being in Europe. Child Indicators Research, 2(3), 319–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-009-9037-7

Chen, J. D., Rong, S. S., & Song, M. L. (2020). Poverty vulnerability and poverty causes in rural china. Social Indicators Research, 1-27.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02481-x

Cheng, L. C. (2019). Policy innovation and policy realisation: the example of children future education and development accounts in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development.1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2019.1571942

Conger, R. D., Ge, X., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65(2), 541–561. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131401

Coravalan, C., Amigo, H., Bustos, P., & Rona, R. (2005). Socioeconomic risk factors for asthma in Chilean young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 95(8), 1375–1381. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2004.048967

Deng, S., Huang, J., Jin, M., & Sherraden, M. (2014). Household assets, school enrollment, and parental aspirations for children’s education in rural china: Does gender matter? International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(2), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12034

Dou, D. Y., Shek, D. T. L., & Kwok, R. (2020). Perceived Paternal and Maternal Parenting Attributes among Chinese Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238741

Duncan, G. J., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Klebanov, P. K. (1994). Economic Deprivation and Early Childhood Development. Child Development, 65(2), 296–318. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131385

Duncan, G. J., Yeung, W. J., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Smith, J. R. (1998). How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review, 63(3), 406–423. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657556

Duncan, G. J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). Family Poverty, Welfare Reform, and Child Development. Child Development, 71(1), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00133

Elliott, W., & Beverly, S. (2011). Staying on course: The effects of savings and assets on the college progress of young adults. American Journal of Education, 117(3), 343–374. https://doi.org/10.1086/659211

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (2001). Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data —or tears: An application to educational enrollment in states of India. Demography, 38(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2001.0003

Friedline, T., Masa, R. D., & Chowa, G. A. (2015). Transforming wealth: Using the inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS) and splines to predict youth’s math achievement. Social Science Research, 49, 264–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.08.018

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Coupet, S., Egler, L., Mattis, J., & Banyard, V. (1996). Interpersonal relationships and adjustment of children in homeless and economically distressed families. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(3), 250–261. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2503_1

Grinstein-Weiss, M., Johanna, K. P. G., Yeong, H. Y., Susanna, S. B., Mathieu, R. D., & Roberto, G. Q. (2009). The Impact of Low- and Moderate-Wealth Homeownership on Parental Attitudes and Behavior: Evidence from the Community Advantage Panel. Children & Youth Services Review, 31, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.05.005

Grinstein-Weiss, M., Shanks, T. R. W., & Beverly, S. G. (2014). Family assets and child outcomes: Evidence and directions. The Future of Children, 24(1), 147–170. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2014.0002

Gwatkin, D. R., Rustein, S., Johnson, K., Pande, R., & Wagstaff, A. (2000). Socio-Economic Differences in Health, Nutrition, and Population in Kenya. World Bank.

Guo, Y., Chen, X., Gong, J., Li, F., & Wang, L. (2016). Association between spouse/child separation and migration-related stress among a random sample of rural-to-urban migrants in wuhan, china. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0154252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154252

Haveman, R., & Wolfe, B. (1994). Succeeding Generations: On the Effects of Investments in Children. Russell Sage Foundation.

Han, C. K., & Chia, A. (2012). A preliminary study on parents saving in the child development account in singapore. Children & Youth Services Review, 34(9), 1583–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.04.011

Hong, R. (2007). Effect of economic inequality on chronic childhood undernutrition in ghana. Public Health Nutrition, 10(04), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980007226035

Huang, J., Nam, Y., & Sherraden, M. S. (2013). Financial knowledge and child development account policy: A test of financial capability. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 47(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12000

Kim, Y., Sherraden, M., Huang, J., & Clancy, M. (2015). Child development accounts and parental educational expectations for young children: Early evidence from a statewide social experiment. Social Service Review, 89(1), 99–137. https://doi.org/10.1086/680014

Kim, Y., Huang, J., Sherraden, M., & Clancy, M. (2017). Child development accounts, parental savings, and parental educational expectations: A path model. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.05.021

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2008). Aspirations, Adaptation and Subjective Well-Being of Rural-Urban Migrants in China. Discussion Paper Series No.381. Department of Economics, University of Oxford.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Fung, A. L. (2021). Editorial: Special Issue on Quality of Life among Children and Adolescents in Chinese Societies. Applied Research Quality Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09915-9

Leventhal, T., & Newman, S. (2010). Housing and child development. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(9), 1165–1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.008

Li, C., Wu, Q., & Liang, Z. (2017). Effect of Poverty on Mental Health of Children in Rural China: The Mediating Role of Social Capital. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9584-x

Lindsey, D. (1995). Child poverty and welfare reform. Children and Youth Services Review, 17(1–2), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/0190-7409(95)00014-4

Lindsey, D., & Shlonsky, A. (2008). Child welfare research: Advances for practice and policy. Oxford University Press.

Lippman, L. H., Moore, K. A., & McIntosh, H. (2011). Positive indicators of child well-being: A conceptual framework, measures, and methodological issues. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 6(4), 425–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-011-9138-6

Loke, V., & Sherraden, M. (2009). Building assets from birth: A global comparison of child development account policies. International Journal of Social Welfare, 18(2), 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2008.00605.x

Lu, Y.-Y., Chen, H.-T., Wang, H.-H., Lawrenz, F., & Hong, Z.-R. (2019). Investigating Grade and Gender Differences in Students’ Attitudes toward Life and Well-Being. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09746-9

Luo, C., Li, S., & Sicular, T. (2020). The long-term evolution of national income inequality and rural poverty in china. China Economic Review, 62, 101465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101465

McKernan, S. M., Ratcliffe, C., & Vinopal, K. (2009). Do assets help families cope with adverse events? Urban Institute.

Mclanahan, S. (2000). Family, state, and child well-being. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 703–706. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.703

McGowen, B. G., & Lindsey, D. (1995). The Welfare of Children. Political Science Quarterly, 110(3), 478.

Nicholas, Z., Kristin, A. M., Ellen, W. S., Thomas, S., & Mary, J. C. (1995). The life circumstances and development of children in welfare families: A profile based on national survey data. In P. L. Chase-Lansdale, & J. Brooks-Gunn (Eds.), Escape from poverty: What makes a difference for children? (pp. 50–59). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results (volume III): Students’ well-being. OECD Publishing.

Orr, A. J. (2003). Black-white differences in achievement: The importance of wealth. Sociology of Education, 76(4), 281–304. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519867

Parker, S., Greer, S., & Zuckerman, B. M. (1989). Double jeopardy: The impact of poverty on early child development. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 35(6), 1227–1240. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36580-4

Pfeffer, F. T., & Hällsten, M. (2012). Mobility regimes and parental wealth: The United States, Germany, and Sweden in comparison (PSC Research Report 12–766). Population Studies Center.

Qi, S. J., Hua, F. R., Zhou, Z., & Shek, D. T. L. (2020). Trends of Positive Youth Development Publications (1995–2020): A Scientometric Review. Applied Research Quality Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09878-3

Sherraden, M. (1991). Assets and the Poor: A New American Welfare Policy. M.E. Sharpe.

Shek, D. T. L. (1995). Chinese Adolescents’ Perceptions of Parenting Styles of Fathers and Mothers. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 156(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1995.9914815

Shek, D. T. L. (2008). Economic disadvantage, perceived family life quality, and emotional well-being in Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal study. Social Indicators Research, 85(2), 169–189.

UNICEF. (2019). UNICEF's Global social protection programme framework. Retrieved on April 16, 2020 from https://www.unicef.org/reports/global-social-protection-programme-framework-2019

Xie, Y., & Lu, P. (2015). The sampling design of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Chinese Journal of Sociology, 1(4), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150x15614535

Xu, H., & Xie, Y. (2015). The causal effects of rural-to-urban migration on children’s well-being in china. European Sociological Review, 31(4), 502–519. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv009

Zhan, M., & Sherraden, M. (2003). Assets, expectations, and children’s educational achievement in female-headed households. Social Service Review, 77(2), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1086/373905

Zhan, M., & Sherraden, M. (2011). Assets and liabilities, educational expectations, and children’s college degree attainment. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(6), 846–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.12.006

Zhang, J., Yang, Y., & Wang, H. (2009). Measuring subjective well-being: A comparison of China and the USA. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 12(3), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839x.2009.01287.x

Zhang, Y. X., Wang, Z. X., Zhao, J. S., & Chu, Z. H. (2016). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in Shandong, China: Urban–rural disparity. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 62(4), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmw011

Zhou, Z., Shek, D. T. L., Zhu, X. Q., & Dou, D. Y. (2020a). Positive youth development and adolescent depression: A longitudinal study based on mainland Chinese high school students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124457

Zhou, Z., Shek, D. T. L., & Zhu, X. Q. (2020b). The importance of positive youth development attributes to life satisfaction and hopelessness in mainland Chinese adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 553313. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.553313

Zhou, Q. S., Guo, S. L. Y., & Lu, H. J. (2020c). Well-Being and health of children in rural China: The roles of parental absence, economic status, and neighborhood environment. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09859-6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, S., Liu, H., Hua, F. et al. The Impact of Household Assets on Child Well-being: Evidence from China. Applied Research Quality Life 17, 2697–2720 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09993-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09993-9