Abstract

Literature has established that, on a macroeconomic level, income inequality has a negative effect on average life satisfaction. An unresolved question is, however, which income groups are harmed by income inequality. In this paper we investigate this relationship at the microeconomic level combining national indicators of income inequality with individual data of life satisfaction from the World Values Survey for 39 countries over a period of 25 years. Tests on moderation by income category show that the Gini coefficient is most negatively related to life satisfaction of the lowest income groups, but the negative effects also extends to other income groups. For the income share of the top 1% we find a similar result. These findings show that income inequality is especially a concern for the lower income groups, but that the harmful effect of income inequality also spillovers to the life satisfaction of other income groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent research has shown a negative relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction on a macroeconomic level (Oshio and Kobayashi 2010; Verme 2011; Graafland and Lous 2018). In the search for a microeconomic explanation, there are two lines of reasoning in the literature. First, it is argued that income inequality causes social distance because it has severe negative consequences for specific groups in society (low income, powerless, minorities) (Becchetti et al. 2014). Because of the magnitude of the effect of income inequality on life satisfaction on these low-income groups, the average level of life satisfaction for the country is also reduced. If this explanation is correct, we would expect that the negative effect of income inequality on life satisfaction is moderated by the income class. Individuals belonging to low-income groups would then be more sensitive to income inequality than individuals from other income groups. In a second approach, defended amongst others by Wilkinson and Pickett (2009, 2010), income inequality undermines social cohesion more generally, both of which are essential to a stable and satisfied society. According to this approach, income inequality affects all groups in society, including the well-off.

Whereas Becchetti et al. (2014) and Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) based their conclusions on national data, definitive micro evidence of the moderating influence of income class on the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction is still lacking. Several articles have tried to address this relationship in different ways, but the results are ambiguous. One micro study on the relationship between socio-economic inequalities and life satisfaction by Fahey and Smyth (2004) found that the impact of inequality depends on the countries’ level of GDP per capita. In their European sample, in the relatively poor countries the impact seems to be much higher than in the richer countries. However, because of data limitations they did not include an indicator for individual household income, thereby leaving out a variable that captures the specific socioeconomic situation of the individuals in the sample. Alesina et al. (2004) claimed that inequality does affect individual happiness. However, they only looked at micro-inequality, leaving unanswered whether their conclusion also applies to national inequality, while also not addressing the possibility that (part of) the impact of their inequality indicator might be caused by national inequality. Other studies have focused only on specific categories of individuals (Levin et al. 2011), or lack important control variables (Zagorski et al. 2014).

In this paper we will focus on the following research question: how is the relationship between income inequality moderated by individual income class? We try to answer this question using data from the World Value Studies and European Value Studies combined with national income inequality data. The research findings will allow us to better understand how income inequality is related to life satisfaction. The paper is structured as follows. First, we discuss theories about the relationship between income inequality and individual life satisfaction and the moderating influence of income class on that relationship. Next, we present the methodology of our analysis, followed by the results. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the results and recommendations for further research.

Theoretical Framework

In this section, we present the theoretical framework. First, we discuss the relationship between national income inequality and individual life satisfaction, and the different microeconomic theories about the macroeconomic relationship. Next, we discuss the moderating influence of income on the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction. The last section presents the specification of the model that we will estimate.

(National) Income Inequality and Life Satisfaction

While the debate on the magnitude and effects of income inequality in market economies has been going on for some decades (Berggren 1999; Gwartney et al. 2004; Wilkinson and Pickett 2010; Stiglitz 2012; Piketty 2014), its relationship to subjective wellbeing has only recently attracted serious attention from economists (Oshio and Kobayashi 2010; Berg and Veenhoven 2010; Verme 2011; Hajdu and Hajdu 2014). Most economic literature linking subjective wellbeing to national income inequality consists of case studies of specific countries (Oshio and Kobayashi 2010; Hajdu and Hajdu 2014; Zagorski et al. 2014). Only a few studies use a cross-country model, but in these studies the relationship between subjective wellbeing and income inequality is not the main focus (Berg and Ostry 2011; OECD 2012; Ostry et al. 2014). Initial studies into this relationship tended to look at happiness. More recent studies have focused on life satisfaction, or a combination of wellbeing indicators (Verme 2011; Hajdu and Hajdu 2014; Zagorski et al. 2014). Although much of the literature on subjective wellbeing focuses on happiness, which is associated with emotions and short-term satisfaction, for macroeconomic evaluations life satisfaction is more interesting due to its evaluative and long-term nature.

Most studies have confirmed a negative relationship at the macroeconomic level (Clark 2018). Oshio and Kobayashi (2010) concluded that national income inequality strongly decreases (average) happiness. In his broad overview study, Verme (2011) found that the significance of the relationship between inequality and life satisfaction depends on the indicator for inequality. In addition, after synchronizing different measures and research methods, he found that income inequality has a significant and negative impact on life satisfaction. Graafland and Lous (2018) found confirmation for a negative relationship between national income inequality and life satisfaction, in which income inequality functions as a mediator in the relationship between economic freedom and life satisfaction.

In contrast, one study by Berg and Veenhoven (2010) found that income inequality is positively related to average happiness. There may indeed be arguments for this type of relationship. Schneider (2012) showed that cultural perceptions that perceive income inequality as proof of the possibility of social mobility or as a necessary incentive to work harder, could generate a positive relationship between income inequality and happiness. An example is the ‘American Dream’, which assumes that everyone who works hard can become rich. Even if this ‘dream’ may be an illusion, it can generate positive incentives and greater happiness. In the literature, this is referred to as the ‘tunnel effect’ (Hirschmann 1973). Another example is the expectation among former Soviet countries, after the transition to a capitalist economic system in the early 1990s. Eggers et al. (2006) found that Russians in regions with high unemployment were happier, regardless of their own status. The reason for this was the positive expectation of long-term wealth following these capitalist reforms.

Besides research into the direct relationship between national income inequality and subjective well-being, a number of studies have introduced macroeconomic research into the relationship between income inequality and variables that indirectly affect subjective wellbeing. Kahn et al. (2000) showed a link between income inequality and low maternal health. Sturm and Gresenz (2002) linked income inequality to chronic illnesses and mental ill-health. In addition, income inequality has been shown to lower the quality of the social environment (Helliwell et al. 2009). This lower quality of the social environment manifests itself in crime statistics. For example, Elgar and Aitken (2011) concluded that income inequality correlates with higher homicide figures. Oishi et al. (2011) claimed that the increased happiness associated with lower income inequality is explained by perceived fairness and general trust. Guimaraes and Sheedy (2012) linked distrust, resulting from power differences and differences in happiness, to a higher risk of social unrest, of which higher crime is one example. Mau et al. (2012) related social inequality to decreased social security. During the last decade, both the IMF (Berg and Ostry 2011; Bastagli et al. 2012; Ostry et al. 2014) and the OECD (2012) have produced critical studies on the social impact of income inequality. It is clear from the literature that income inequality negatively affects variables closely related to social cohesion at the macro level.

On the micro level, there are a few studies that have examined the relationship between life satisfaction and national income inequality. Whereas Schneider (2012) showed the importance of perceptions in evaluating income inequality (see also Bavetta et al. 2019), Helliwell et al. (2009) found that the social environment is much more important than income to subjective well-being, as well as comparison to reference groups (Budría and Ferrer-I-Carbonell 2019). However, Zagorski et al. (2014) found no direct effect from the Gini coefficient on individual life satisfaction. Levin et al. (2011) also found no association of income inequality with individual life satisfaction, but they only looked at the impact of income inequality on the life satisfaction of adolescents, not a sample representative of the whole population of a country. Haller and Hadler (2006) found that life satisfaction is higher in countries with low inequality. However, they used data from only one wave of the World Values Studies. Finally, Fahey and Smyth (2004) did find some effect from income inequality on life satisfaction, but they suggested that this might have been influenced by the timing of the data they use.

Income Inequality and Life Satisfaction: Moderation by Income Class

An unresolved question about how national income inequality affects average life satisfaction in a society is whether income inequality only decreases the life satisfaction of specific groups or whether the negative relationship applies more generally. In literature, two strands of reasoning can be identified.

In the first approach, the negative effect of national income inequality on average life satisfaction in society is explained by its negative consequences for low income groups in society (Becchetti et al. 2014). If high income inequality goes hand in hand with a perception of low social mobility opportunities, or worse, a sense of powerlessness and oppression of the less well-off, then the accumulation of disadvantages will have a major negative effect on the life satisfaction of these ‘losers’ and the severity of their dissatisfaction will affect average life satisfaction (Caruso and Schneider 2011). This line of reasoning finds support in Mau et al. (2012), who reported that high income inequality seems to hit the socio-economic security of the lower classes, such as unskilled manual workers, much harder than other social classes. This would mean that income category moderates the influence of national income inequality on individual life satisfaction: the lower the income of an individual, the stronger income inequality affects individual life satisfaction. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1 The individual life satisfaction of lower-income groups is negatively related to income inequality at the national level.

H2 The negative relationship between income inequality and individual life satisfaction is stronger for lower-income groups than for higher-income groups.

In contrast, Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) argue that income inequality will reduce average life satisfaction through a reduction in individual life satisfaction in all social classes. Income inequality creates social distance, undermining trust throughout the income distribution. Not only does this affect lower incomes, it also causes a lower life satisfaction among higher-income households, since the social distance and consequent lower trust cause insecurity and stress. Furthermore, Piketty (2014) argues that income inequality should be viewed as the single phenomenon to which many of the symptoms of the failure of our modern societies can be traced, for example lower life expectancy, high CO2 emissions, and, more generally, poor physical and mental health. As such, income inequality theoretically functions as a summary indicator, signaling the structural dysfunction of societies rather than being a mere side-effect of market economies. Based on this, we propose as an additional hypothesis:

H3 The individual life satisfaction of higher-income groups is negatively related to income inequality.

Model Specification

Based on the sections above, we define the following model:

Sub-index i stands for the individual, sub-index k for country, sub-index t for time. LSi,k,t denotes individual life satisfaction, IIk,t denotes income inequality, and yi,k,t, denotes income group. Zk,t denotes the country-level control variables, while Xi,k,t denotes the set of variables to control for individual-level variation. Tt stands for the time dummies included in the model and Dk for (n) country dummies. This model describes the moderation of the relationship between macroeconomic income inequality and individual life satisfaction by personal income group. The model includes 5 (n) interaction dummies, one for each income group.

Data and Methods

In this section we describe the data and methodology we used for our research, starting with the sources and measurement methods of the dependent variable and the independent variables. Then we discuss the choice and measurement of control variables, followed by a description of the estimation technique used.

Data Sources and Measurement

In order to test our hypotheses, we use data from the integrated sample of World Values Survey and European Values Survey (WVS/EVS). These are complemented by country data from Solt’s World Income Inequality Database (SWIID, Solt 2016), the World Inequality Database (WID) and the World Bank. The dataset consists of 138,193 observations from 39 countries, including 22 European countries, 6 Asian countries, 5 countries from the Middle East and North Africa, 2 Latin American countries and 4 other Western countries.Footnote 1 We have data from the last five different waves of the WVS, which are carried out approximately every 5 years. Wave 2 has data from 1989 to 1994, Wave 3 has data from 1995 to 1997, Wave 4 has data from 1999 to 2004, Wave 5 has data from 2004 to 2009, and Wave 6 has data from 2010 to 2014. For each country, we have data from at least two waves (Table 1).

The dependent variable, individual life satisfaction, is measured as a number on a scale from 1 to 10 in answer to the question ‘How satisfied are you with your life?’. National income inequality is measured by the net Gini coefficient, which is the Gini-coefficient of GDP corrected for redistribution through taxes. A major criticism that has gained support in recent years is that common macroeconomic indicators of inequality, such as the Gini coefficient, underestimate inequality at the extremes of the income distribution (Becchetti et al. 2014; Piketty 2014). Alternatives are to look either at the share of pre-tax national income earned by the richest 1% (Jenkins 2015).Footnote 2

Regarding the personal income level, absolute statistics are unfortunately lacking in the WVS data, which instead reports income levels on a scale from 1 to 10. The data are nonetheless useful for evaluating how different income groups perceive and experience income inequality (see also Bjørnskov et al. 2008; Fahey and Smyth 2004; Haller and Hadler 2006). In our regression analysis, we work with a set of dummies for each income group instead of the generic categorical variable in order to more clearly observe what the impact is of income inequality on the life satisfaction of various income groups.

Except for the dummy variables, which can only take the values 0 or 1, we standardized all variables in order for the coefficients to be compared more easily.

Control Variables

We included a number of individual and country level control variables. We mostly follow the literature in this, especially earlier studies using WVS data. Bjørnskov et al. (2008) has the most complete set of control variables and this paper is our starting point, but we limit the set of variables to avoid over identification and multicollinearity. In deciding which control variables to keep, we followed several other papers that have used WVS data, as well as the theories discussed above.

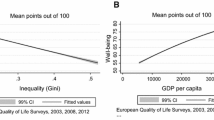

First of all, national income per capita has been shown to be an important determinant of life satisfaction due to its effect on consumption, health, and education level (Dolan et al. 2008; DiTella and MacCulloch 2010). It not only seems to be important to average life satisfaction at the country level: Fahey and Smyth (2004) show it also affects individual life satisfaction (also Bjørnskov et al. 2008). Income per capita was measured by taking the natural logarithm of the World Bank statistic. As specification we used Purchasing Power Parity at constant 2011 US dollars. Furthermore, following Ovaska and Takashima (2006) we included political rights and civil liberty. We also controlled for inflation, as previous research has shown that inflation is related to income inequality (Erosa and Ventura 2002) and to life satisfaction (Ovaska and Takashima 2006).

In addition, we included some personal characteristics such as marital status, gender, and age (Bjørnskov et al. 2008; Fahey and Smyth 2004; Haller and Hadler 2006). For age, in our regression analysis we again followed Bjørnskov et al. (2008) by splitting the variable into six dummies for different age groups in order to be able to see how the effect on life satisfaction differs per category, to get a more precise picture. Marital status consists in our model of a dummy for people who are married or live together as married. Haller and Hadler (2006) found, for example, that married persons and persons with children are happier than divorced individuals. This variable furthermore captures to some extent the connectedness of a person, and the role of relationships in that person’s life. We also included a variable on whether an individual is unemployed (see Guvenen et al. 2017). In addition to these characteristics, we include five religion variables. First, we included an indicator for the religiosity of individuals, which is shown to be of great importance in shaping individual behavior (Yeniaras and Akarsu 2017). This indicator is defined as an answer from 1 to 10 to the question ‘How important is God in your life?’, where ‘God’ can be defined in different ways. The advantage is that in this way even non-theistic religiosity can be included, as well as forms of religiosity that do not fit standard categories. The other indicators are a set of dummies based on the religious tradition with which individuals associate. We have first of all a dummy indicating whether the person is an adherent of protestant Christianity or not (Bjørnskov et al. 2008; Haller and Hadler 2006). We chose to include this branch of Christianity since Protestantism provides strong structures for life and also has clearly defined political views. These views are often seen as a major explanation of the development of different social systems between Northern and Southern Europe. Second, we include a dummy for adherence to Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions. We created one dummy for both of these, following Bjørnskov (2006) who makes a distinction between hierarchical traditions, such as these branches of Christianity, and non-hierarchical traditions like Protestantism. In addition, we include an indicator for Muslims, as this is a unique tradition that strongly influences life attitudes, and for people from other religions.

Since we used data from multiple waves, we included time dummies for each wave. Finally, to control for unobserved heterogeneity between countries, we included dummies for all countries.

Estimation Technique

As we have data from multiple waves, we used a least squares dummy variable model with country and time dummies. Since the observations of different waves do not concern the same persons, we cannot run a panel regression model, in which the individuals are the panel variable and the waves the time dimension. We performed White tests and found evidence of heteroscedasticity. In order to correct for this, we used robust standard errors. Furthermore, we checked for problematic correlation between the different variables included in the model by calculating the Pearson-Watson correlation coefficients. We did not find indications for this. However, we nonetheless calculated the VIF-factors as an extra check, which confirmed the conclusion that there is no need to worry about multicollinearity.

Regarding endogeneity, theoretically there is little reason for reversed causality from (individual) life satisfaction to (national) income inequality. There are also no theoretical reasons that any remaining simultaneity bias is larger or smaller for high income than for low income groups. Furthermore, the use of time and country dummies in combination with other control variables substantially reduces the chance that our results are biased because of unobserved heterogeneity between countries. However, we acknowledge that endogeneity may still be possible if there are unobserved variables that correlate both with income inequality or its interaction with income group and with individual life satisfaction. Ideally we would empirically test the causality by the use of instrumental variables, which is unfortunately very difficult in the type of analysis we conduct. Therefore, we should be careful with interpreting the test results in terms of causality, and treat them as reflecting correlations.

Empirical Results

Bivariate Correlation Analysis

Table 2 presents the Pearson-Watson correlation coefficients of the main variables considered in our analysis. Generally, correlation coefficients are low but significant. Life satisfaction correlates negatively with the income inequality indicators and positively with GDP per capita and personal income. None of the correlations are surprising.

Results of Regression Analysis

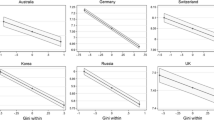

Table 3 reports the regression results. The first column shows the model with the Net Gini coefficient as the indicator for the level of income inequality in a country. We find that income inequality is significantly negatively related to individual life satisfaction. When the share of national income earned by the top 1% is used as an alternative (column 2), the relationship is again negative and significant. These results show that income inequality is significantly negatively related to individual life satisfaction. Note, furthermore, that the net Gini coefficient explains life satisfaction better than the share of income of the top 1%.Footnote 3

The follow-up question is what the source is of this relationship. In order to test whether this follows from a negative relationship between life satisfaction and income inequality on all income groups, or only from an exceptionally strong negative relationship with the lower group(s), columns 3 and 4 report regressions with interaction dummies between the different income inequality indicators and (income) quintiles. For the Gini coefficient (column 3), the results show that all income quintiles experience a significant negative relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction. The relationship is, however, most negative for the lowest two quintiles, while it becomes less negative when personal income level increases. For the income share of the top 1%, we find a similar result except that only for the highest income quintile income inequality is no longer significant. The F-tests show that all three sets of interaction dummies are significant in explaining individual life satisfaction.Footnote 4

These results mean that we find support for H1, as the life satisfaction of the lowest income quintiles is negatively related to income inequality. Furthermore, we find that the interaction term between income inequality and the highest income group is significant in column 3 where the net Gini coefficient is used, but not in column 4. However, given that the net Gini coefficient provides a better explanation for life satisfaction than the income share of the top 1%, we conclude that the results also support H3.Footnote 5

In order to test hypothesis 2, we calculated the significance of the difference in the estimated coefficients of the interaction terms for the various income groups, taking the highest income group as a reference. The results are reported in Table 4.

The results show support for H2 as the difference in the estimated interaction terms between the lowest and highest income groups is significant, both for the lowest income group and the one but lowest income group. This result is robust for the measurement of income inequality (net Gini or top 1%).

As for the other variables in the model, there are no surprising results, except that GDP per capita is not significantly related to individual life satisfaction and that having more political rights is negatively related to life satisfaction. This latter result is in line with the findings of Ovaska and Takashima (2006) who explained it as a reflection that democracy is not ideal as a collective decision making mechanism. Inflation is found to have a small, but significant negative relationship with life satisfaction, which is in line with previous literature. Life satisfaction increases significantly with personal income level, although the difference between the fourth and fifth (the reference quintile) income quintiles is not significant. Marriage, religiosity and Protestantism correlate significantly and positively with life satisfaction, whereas the coefficients for the other religious traditions do not show a significant relationship. Furthermore, unemployed people are less satisfied, while for age, the happiest are those under 25, followed by those who get to enjoy their pension as well as those between 25 and 34, whose life satisfaction does not differ significantly from that of the reference group. The 45–54 age group are the least happy. Finally, our model shows that there are no significant time trends in life satisfaction, although during the earlier waves (Wave 3 and 4) life satisfaction was significantly lower.

Discussion

Summary of Results

This paper studies the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction. While a significant negative relationship has been confirmed at the macroeconomic level, it is unclear what is behind this relationship at the microeconomic level. We developed three hypotheses to be tested with a large dataset of 138,193 observations from 39 countries, taken from five waves spanning more than 25 years. Our research first of all finds indications that the significant negative relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction at the macro level also holds at the micro level. This result is important as it highlights that income inequality is a cause for concern both at the macroeconomic and at the microeconomic level.

Second, we find that the negative relationship with life satisfaction is strongest for the lowest income quintiles. However, the results suggest that although life satisfaction of lower income groups seems to be more negatively related to income inequality, income inequality is also significantly negatively related to life satisfaction of other income groups. Whereas the first finding supports the argument of Becchetti et al. (2014) that income inequality is especially a concern for the lower income groups, the second finding gives some support to the analysis of Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) that this concern also affects the life satisfaction of other income groups.

Contribution to Literature

The analysis presented above is the first in which different theories about the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction are empirically tested using micro-level data that includes the life satisfaction of individuals.

With respect to the scientific literature, our research, first of all, strengthens macroeconomic analyses that found a negative relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction and improves the credibility of their results (Oshio and Kobayashi 2010; Verme 2011; Hajdu and Hajdu 2014; Graafland and Lous 2018). It provides a microeconomic underpinning of this relationship, showing that national income inequality is negatively related to the life satisfaction of individuals from different layers of society. As for concerns of comparability, our dataset includes many countries from all continents, cultures and historical backgrounds. By differentiating the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction for different income groups in societies, our research provides empirical confirmation of previous research suggesting that inequality is related to the life satisfaction of more people than only the lower income classes (Wilkinson and Pickett 2010; Piketty 2014).

Limitations and Future Research

One of the limitations of this research is that causality has not been solved econometrically in a satisfactory way. Although we implemented several procedures to limit the chance of endogeneity and gave arguments that in the relations we investigate reverse causality is unlikely, we were unable to definitely test the way in which causality runs, mainly because of the lack of suitable instrumental variables and other data limitations.

Furthermore, WVS does not have many data on alternative grouping variables, which limits the options for assigning vignettes in order to compare different population groups (see Kapteyn et al. 2009). However, one interesting option is to use WVS data on social status instead of income class. According to Wilkinson and Pickett (2019) low social status is associated with elevated levels of stress, and how inequality affects rates of anxiety and depression. Future research could therefore investigate to what extent it is low social status rather than low income that moderates the relationship between income inequality and well-being.

In addition, there is potential for researching alternative moderators in the relationship between inequality and life satisfaction. For example, research could specifically address the question of how cultural norms affect the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction, both between countries and within countries. Income-inequality in a nation may thus have positive as well as negative effects on happiness, the balance of which will vary across time and nations. This raises the question how large the impact of cultural perceptions is on the effect of income inequality on happiness. Especially regarding the perception of more directly observed indicators of inequality such as the income share of the top 1%, which is a relatively new measure in terms of availability for a large set of countries with vast opportunities for further research. Another moderating factor might be inequality itself. One could argue that society needs a certain degree of inequality to function well and that people accept this level of inequality without negative effects on their life satisfaction.

It would also be interesting to dig deeper into the connection of income inequality with other indicators of human flourishing, for example by substituting life satisfaction for social indicators such as trust or other estimators of social cohesion. A related option for future research is to test if trust mediates the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction at the micro level. As Oishi et al. (2011) claimed, the increased happiness associated with lower income inequality is explained by perceived fairness and general trust. Future research could provide additional insight in this mediation channel by combining it with moderation effects, i.e. by testing whether the relationships between income inequality and trust and between trust and life satisfaction differ for different income classes.

Finally, an extension of the research in which income inequality is substituted by wealth inequality would provide interesting insights in long term patterns of economic organization. Unfortunately, this is only possible for a limited set of countries, but combined with the WVS data, it might now be possible to define a model that is robust and meaningful (Table 5).

Notes

An overview of the countries included in the dataset can be found in the Appendix.

The 1% share refers to the pre-tax national income share held by the 99–100 percentile group. Pre-tax national income is the sum of all pre-tax personal income flows accruing to the owners of the production factors, labor and capital, before taking into account the operation of the tax/transfer system, but after taking into account the operation of pension system. The population is comprised of individuals over age 20. The base unit is the individual (rather than the household).

If we include both net Gini and the share of income of the top 1%, the net Gini coefficient remains significant, whereas the share of income of the top 1% becomes insignificant.

If we also controlled for quadratic income inequality (Ozer-Balli and Sørensen (2013), the results remain robust.

We also ran a model excluding the two Latin American countries, which are known historically to have high levels of inequality, yet high life satisfaction. The results, however, are almost identical to the current model that includes these countries. Therefore we prefer a large dataset.

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Bastagli, F., Coady, D., & Gupta, S. (2012). Income inequality and fiscal policy. IMF Staff Discussion Note, SDN/12/08, International Monetary Fund.

Bavetta, S., Li Donni, P., & Marino, M. (2019). An empirical analysis of the determinants of perceived inequality. Review of Income and Wealth, 65(2), 264–293.

Becchetti, L., Massari, R., & Naticchioni, P. (2014). The drivers of happiness inequality: Suggestions for promoting social cohesion. Oxford Economic Papers, 66(2), 419–442.

Berg, A., & Ostry, J. (2011). Inequality and unsustainable growth: Two sides of the same coin? IMF Staff Discussion Note, SDN/11/08, International Monetary Fund.

Berg, M., & Veenhoven, R. (2010). Income inequality and happiness in 119 nations. In B. Greve (Ed.), Social policy and happiness in Europe (pp. 174–194). Cheltenham: Edgar Elgar.

Berggren, N. (1999). Economic freedom and equality: Friends or foes? Public Choice, 100(3–4), 203–223.

Bjørnskov, C. (2006). Determinants of generalized trust: A cross-country comparison. Public Choice, 130, 1–21.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. (2008). Cross-country determinants of life satisfaction: Exploring different determinants across groups in society. Social Choice Welfare, 30, 119–173.

Budría, S., & Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A. (2019). Life satisfaction, income comparisons and individual traits. Review of Income and Wealth, 65(2), 337–358.

Caruso, R., & Schneider, F. (2011). The socio-economic determinants of terrorism and political violence in Western Europe (1994-2007). European Journal of Political Economy, 27, S37–S49.

Clark, A. E. (2018) Four decades of the economics of happiness: Where next?. Review of Income and Wealth, 64(2), 245–269.

DiTella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2010). Happiness adaptation to income beyond ‘basic needs’. In E. Diener, J. Helliwell, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), International differences in well-being (pp. 217–247). New York: Oxford University Press.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 94–122.

Eggers, A., Gaddy, C., & Graham, C. (2006). Unemployment and wellbeing in Russia in the 1990’s: Can society’s suffering be individuals’ solace? Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 209–242.

Elgar, F., & Aitken, N. (2011). Income inequality, trust and homicide in 33 countries. European Journal of Public Health, 21(2), 241–246.

Erosa, A., & Ventura, G. (2002). On inflation as a regressive consumption tax. Journal of Monetary Economics, 49(4), 761–795.

Fahey, T., & Smyth, E. (2004). Do subjective indicators measure welfare? Evidence from 33 European societies. European Societies, 6(1), 5–27.

Graafland, J., & Lous, B. (2018). Economic freedom, income inequality and life satisfaction in OECD countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(7), 2071–2093.

Guimaraes, B., & Sheedy, K, D. (2012). A model of equilibrium institutions. CEPR discussion paper, no. DP8855.

Guvenen, F., Karahan, F., Ozkan, S., & Song, J. (2017). Income inequality within and across firms: Heterogeneous scarring effects of full-year nonemployment. American Economic Review, 107(5), 369–373.

Gwartney, J., Holcombe, R., & Lawson, R. (2004). Economic freedom, institutional quality, and cross-country differences in income and growth. Cato Journal, 24, 205–233.

Hajdu, T., & Hajdu, G. (2014). Reduction of income inequality and subjective well-being in Europe. Economics: The Open-Access, Open Assessment E-Journal, 8, 2014–2035.

Haller, M., & Hadler, M. (2006). How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhappiness: An international comparative analysis. Social Indicators Research, 75, 169–216.

Helliwell, J. F., Barington-Leigh, C. P., Harris, A., & Huang, H. (2009). International evidence on the social context of well-being. NBER working paper series, no. 14720. Cambridge MA: National Bureau of economic research.

Hirschmann, A. O. (1973). The changing tolerance for income inequality in the course of economic development. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(4), 544–566.

Jenkins, S. P. (2015). World income inequality databases: An assessment of WIID and SWIID. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 13(4), 629–671.

Kahn, R. S., Wise, P. H., Kennedy, B. P., & Kawachi, I. (2000). State income inequality, household income, and maternal mental and physical health: Cross sectional national survey. British Medical Journal, 321, 1311–1315.

Kapteyn, A., Smith, J., & van Soest, A. (2009). Life satisfaction. IZA discussion paper, no. 4015. Bonn: Institute for the Study of labor.

Levin, K. A., Torsheim, T., Vollebergh, W., Richter, M., Davies, C., Schnohr, C., Due, P., & Currie, C. (2011). National income and income inequality, family affluence and life satisfaction among 13 year old boys and girls: A multilevel study in 35 countries. Social Indicators Research, 104, 179–194.

Mau, S., Mewes, J., & Schöneck, N. M. (2012). What determines subjective socio-economic insecurity? Context and class in comparative perspective. Socio-Economic Review, 10, 655–682.

OECD. (2012). Reducing income inequality while boosting economic growth: Can it be done? In P. C. Padoan (Ed.), Economic policy reforms 2012: Going for growth. Paris: OECD.

Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1095–1100.

Oshio, T., & Kobayashi, M. (2010). Income inequality, perceived happiness, and self-rated health: Evidence from nationwide surveys in Japan. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 1358–1366.

Ostry, J., Berg, A., & Tsangarides, C. (2014). Redistribution, inequality, and growth. IMF Staff Discussion Note, SDN/14/02, International Monetary Fund, 14, 1.

Ovaska, T., & Takashima, R. (2006). Economic policy and the level of self-perceived well-being: An international comparison. Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 308–325.

Ozer-Balli, H., & Sørensen, B. E. (2013). Interaction effects in econometrics. Empirical Economics, 45(1), 583–603.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st century. London: Beldknap/Harvard.

Schneider, S. (2012). Income inequality and its consequences for life satisfaction: What role do social cognitions play? Social Indicators Research, 106, 419–438.

Solt, F. (2016). The standardized world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly, 97. SWIID version 6.1, October 2017.

Stiglitz, J. (2012). The price of inequality. London: W. W. Norton & Company.

Sturm, R., & Gresenz, C. (2002). Relations of income inequality and family income to chronic medical conditions and mental health disorders: National survey in USA. British Medical Journal, 324, 20–23.

Verme, P. (2011). Life satisfaction and income inequality. Review of Income and Wealth, 57(1), 111–137.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2009). Income inequality and social dysfunction. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 493–511.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2010). The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin Books.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2019). The innert level: How more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everone’s well-being. London: Penguin Books.

Yeniaras, V., & Akarsu, T. N. (2017). Religiosity and life satisfaction: A multi-dimensional approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 1815–1840.

Zagorski, K., Evans, M., Kelley, J., & Piotrowska, K. (2014). Does national income inequality affect individuals’ quality of life in Europe? Inequality, happiness, finances, and health. Social Indicators Research, 117, 1089–1110.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc. Templeton World Charity Foundation had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lous, B., Graafland, J. Who Becomes Unhappy when Income Inequality Increases?. Applied Research Quality Life 17, 299–316 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09906-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09906-2