Abstract

We assess the recent evolution of the quality of life in Uruguay, analysing whether current subjective well-being levels are conditioned by the objective well-being trajectory of each individual. We explore subjective well-being in 3 domains: life, economic situation and housing satisfaction. Although adaptation has been addressed in the empirical literature for developed countries, there is scarce evidence for developing countries due to the lack of suitable panel datasets. In this article, we provide an econometric test of the adaptation hypothesis based on longitudinal data from Uruguay for the years 2004, 2006 and 2011/12 (Estudio Longitudinal de Bienestar en Uruguay). Our main findings show that present levels of life, economic and housing satisfaction are each positively correlated with the corresponding contemporary and lagged objective variable of interest. Thus, we reject the adaptation hypothesis in all the dimensions considered. We also explore the role of social interactions in the 3 subjective well-being dimensions, finding out that average objective well-being of the reference group (either income or crowding) is not associated with individual subjective well-being levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Differently to Elster, in Nussbam and Sen’s view, reduced aspirations result from being exposed to long-term deprivation, but this does not necessarily entail the existence of a previous period in which individual desires were not downsized.

In recent decades, a significant strand of the empirical literature has been examining reported happiness and life satisfaction as an approximation to measure cardinal utility and its determinants (Clark and Oswald 1994; Blanchflower and Oswald 2000; Easterlin 1995; Frey and Stutzer 2007). Lelkes (2006) offers a complete systematization of the main findings of this literature.

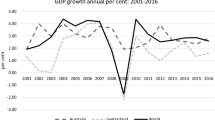

Redistributive policies included the introduction of the personal income tax, a health reform, the restoration of centralized wage-setting mechanisms and a substantial expansion of non-contributory cash transfers schemes.

As in most Latin American countries, national poverty thresholds are based on absolute lines, following the ECLAC methodology, but with a higher Orshansky coefficient. Montevideo’s per capita official poverty line is equivalent to 100 U$S a month. Poverty and inequality figures were calculated by the authors based on micro-data from official household surveys (Encuestas Continuas de Hogares) carried out by Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE).

He also remarks that these relations vary depending on the specific wording of the question used to capture subjective well-being: life satisfaction evaluations and experiencing happiness the day before.

Whereas in this paper we use school groups as the basis of social comparisons, Leites and Ramos define broad categories in terms of education, sex and region and obtain average income from the national household survey (Encuesta Continua de Hogares).

Information on the dataset, survey questionnaires and micro-data can be found at http://www.fcea.edu.uy/estudio-del-bienestar-multidimensional-en-uruguay.html

Details on ECH can be found at http://www.ine.gub.uy/web/guest/encuesta-continua-de-hogares3

Survey instruments can be found at http://www.fcea.edu.uy/estudio-longitudinal-del-bienestar-en-uruguay/datos/cuestionarios.html

A potential source of endogeneity might be given by the fact that improvements in life satisfaction levels could have an impact on income. Di Tella and MacCulloch (2008) conducted empirical tests that suggest that such shocks do not significantly bias the coefficients.

Full regression outputs can be requested from the authors.

Fixed effects estimations yield to different results in the three domains, but divergences are larger in the case of economic satisfaction.

Extreme poverty was measured using the official national threshold (INE 2018). In Uruguay the per capita extreme poverty line corresponds to the monthly monetary value of the food basket needed to meet the daily nutritional requirements of an individual. As in the case of the poverty line mentioned before in this article, is calculated by the National Statistical Office (INE 2006) following ECLAC’s guidelines.

References

Alkire, S. (2002). Dimensions of human development. World Development, 30(2), 181–205.

Amarante V., Arim A., Severi C., Vigorito A. & Aldabe I. (2007). “La situación nutricional de los niños y las políticas alimentarias”. UNDP: Montevideo.

Amarante, V., Colafranceschi, M. & Vigorito, A. (2014). “Uruguay's Income Inequality and Political Regimes over 1981–2010″ en Cornia A. (ed.). Falling Inequality in Latin America. Policy Changes and Lessons, WIDER Studies in Development Economics, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bellet, C. (2017) The paradox of the Joneses: superstar houses andmortgage frenzy in suburban America. CEP discussion paper, CEPDP1462. Centre for Economic Performance (CEP), London, UK.

Bérgolo, M., Leites, M., & Salas, G. (2006). “Privaciones nutricionales: su vínculo con la pobreza y el ingreso monetario”. Documento de Trabajo IECON 03/07.

Blanchflower, D. G. & Oswald, A. J. (2000). “Well-Being Over Time in Britain and the USA”, NBER Working Papers 7487, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Borraz, F., Pozo, S. & Rossi, M. (2008). “And What About the Family Back Home? International Migration and Happiness”, working paper 0308, Departamento de Economía, Universidad de la República.

Bucheli, M. & Rossi, M. (2003). “El grado de Satisfaction con la vida. Evidencia para las mujers del Gran Montevideo”, in Nuevas Formas de Familia. Universidad de la República-UNICEF, Montevideo.

Burchardt, T. (2005). Are one man’s rags another man’s riches? Identifying adaptive expectations using panel data. Social Indicators Research, 74(1), 57–102.

Burdín, G., Esponda, F., & Vigorito, A. (2015). Desigualdad y altas rentas en el Uruguay: un análisis basado en los registros tributarios y las encuestas de hogares del período 2009–2011. In J. P. Jiménez (Ed.), Desigualdad, concentración del ingreso y tributación sobre las altas rentas en América Latina. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL.

Burstin V., Fascioli A., Modzelewski H, Pereira A., Reyes A., Salas G. & Vigorito A. (2010). “Preferencias adaptativas: entre deseos, frustración y logros”, ed. 1, Fin de Siglo: Montevideo.

Cid, A., Ferres, D. & Rossi, M. (2007). “Testing Happiness Hypothesis among the Elderly”, Documentos de Trabajo 1207. Departamento de Economía, Universidad de la República.

Clark, D. (2009). Adaptation, poverty and well-being: some issues and observations with special reference to the capability approach and development studies. Journal of Human Development, 10(1), 21–42.

Clark, D. (2012). Adaptation, poverty and development. The dynamics of subjective well-being. Oxford: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Clark, A. (2016). Adaptation and the Easterlin paradox. In T. Tachibanaki (ed.) Advances in happiness research: A comparative perspective, Springer, pp.75–94.

Clark, A., & Georgellis, Y. (2013). Back to baseline in Britain: adaptation in the British household panel survey. Economica, 80(319), 496–512.

Clark, A., & Oswald, A. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. Economic Journal, 104(424), 648–659.

Clark, A., Kristensen, N., & Westergård-Nielsen, N. (2009). Economic satisfaction and income rank in small Neighbourhoods. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(2–3), 519–527.

Colafranceschi, M., Failache, E., & Vigorito, A. (2014). Desigualdad multidimensional y dinámica de la pobreza: un análisis para Uruguay entre 2006 y 2011. Serie Cuadernos de Desarrollo Humano, N.2. Montevideo: UNDP.

Colafranceschi, M., Leites, M., & Salas, G. (2017). "Progreso multidimensional en Uruguay", Cuaderno de Desarrollo Humano. UNDP, Montevideo (forthcoming).

Comim, F. (2008). Capabilities and happiness: Overcoming the informational apartheid. In L. Bruni, F. Comim, & M. Pugno (Eds.), Capabilities and happiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comim, F., & Teschl, M. (2005). Adaptive preferences and capabilities: some preliminary conceptual explorations. Review of Social Economics, 63(2), 229–247.

Cornia, A. (2010). Income distribution under Latin America's new left regimes. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 11(1), 85–114.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health and well-being around the world: evidence from the Gallup world poll. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 53–72.

Di Tella, R. & MacCulloch, R. (2008). “Happiness adaptation to income beyond “basic needs””, working paper 14539, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Diaz-Serrano, L. (2009). Disentangling the housing satisfaction puzzle: Does homeownership really matter? Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(5), 745–755.

Easterlin, R. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. Nations and households in economic growth, 89, 89–125.

Easterlin, R. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization., 27(1), 35–47.

Elster, J. (1988). Uvas amargas. Sobre la subversión de la racionalidad. Barcelona: Península.

Failache, E., Salas, G., & Vigorito, A. (2016). La dinámica reciente del bienestar de los niños en Uruguay. Un estudio en base a datos longitudinales. Serie Documentos de Trabajo 11/2016. Montevideo: UdelaR.

Festinger, L. (1975). Teoría de la disonancia cognitiva. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Políticos.

Frey, B. & Stutzer, A. (2007). Economics and psychology. A promising new cross-disciplinary field. CESifo Seminar Series, MIT Press.

Gasparini, L. & Lustig, N. (2011). The rise and fall of income inequality in Latin America. In Handbook of Latin American Economics, Chapter 28. Oxford University Press.

Gerstenbluth, M., Rossi, M., & Triunfo, P. (2008). Felicidad y salud: una aproximación al bienestar en el Río de la Plata. Estudios de Economia, 35(1), 65–78.

Graham, C., & Pozuelo, J. R. (2017). Happiness, stress, and age: How the U curve varies across people and places. Journal of Population Economics, 30(1), 225–264.

INE. (2006). Líneas de pobreza e indigencia Uruguay 2006. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. http://www.ine.gub.uy/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=47f01318-5f94-4e1d-9cc9-00b63fa89323&groupId=10181 (last access: 25/01/2018).

INE. (2018). Líneas de pobreza per cápita para Montevideo, Interior urbano e Interior rural. http://www.ine.gub.uy/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=1675e7d0-6fe0-49bd-bf3f-a46bd6334c0c&groupId=10181 (last access: 25/01/2018).

Layard, R. (2007). Happiness and public policy: A challenge to the profession. In B. Frey and A. Stutzeer (Eds.) Economics and psychology. A Promising New Cross-Disciplinary Field. CESifo Seminar Series, MIT Press.

Leites, M. & Ramos, X. (2016). Relative Deprivation and Economic Aspiration: Evidence on Aspiration Failure for a Developing Country. Paper presented at the NIP annual meeting, Uruguayan chapter.

Lelkes, O. (2006). Social Exclusion in Central-Eastern Europe Concept, Measurement and Policy Interventions. Working Paper 200622, Faculty of Economics, Department of Economics. European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research, Vienna and Steps (Portugal).

López Calva, L. F., & Lustig N. (2010). Declining inequality in Latin America: a decade of progress? New York: Brookings/UNDP.

Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being: does happiness change after major life events? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 75–79.

Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development: the capabilities approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Peck, C., & Stewart, K. (1985). Satisfaction with housing and quality of life. Family and Consumer Sciences, 13(4 June), 363–372.

Pereira, G. (2009). Preferencias adaptativas como bloqueo de la autonomía. In A. Cortina & G. Pereira (Eds.), Pobreza y libertad. Madrid: Editorial Tecnos.

Robeyns, I. (2003). Selecting capabilities for quality of life measurement. Social Indicators Research, 74(1), 74–121.

Sen, A. (1987). Commodities and capabilities. Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sabina Alkire, Veronica Amarante, Rodrigo Arim, Andrew Clark, Flavio Comim, Ana Fascioli, Peter Fitermann, Gustavo Pereira, Ambra Poggi, Agustín Reyes, participants at the meetings of the Human Development and Capabilities Association in Lima and ECINEQ in Catania and two anonymous referees for many comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this article. Financial help from Fondo Clemente Estable and Comision Sectorial de Investigación Científica de la Universidad de la República is very gratefully acknowledged. All errors remain our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Annex 1

A comparative analysis of the ELBU data with that from the official household survey (Encuesta Continua de Hogares) run by the local statistical office (INE) in terms of income, employment situation and other socio-economic variables shows very similar results (see Failache et al. 2016) for details). However, as is the case of most household surveys, recent comparisons with information coming from income tax records show that labour earnings and pensions are well captured in the ECH, although top and capital incomes may be undercaptured (Burdín et al. 2015). Informal income is included in the ECH and the ELBU. However, in the period under analysis, 80% of the labour force had formal employment (INE 2018).

Table 6 depicts a comparison between data from ECH for 2004 and the first ELBU wave run the same year. In order to pick similar children at ECH, in column (1) we include all children attending first grade at primary schools in Montevideo and the Metropolitan area, and in column (2), we restrict the sample to the sub-group attending public schools, which be a closer comparison to ELBU. In regard to ELBU, the observations included in column (3) correspond to the balanced panel used in this study, whereas column (4) includes all cases for Montevideo and the Metropolitan gathered in the first wave. The comparison among the two columns allows to assess the effect of panel attrition on the indicators included in the Table.

A first set of indicators was computed at the household level (average years of education, crowding, per capita household income). A second group attempts to capture the characteristics of ELBU respondents. Although in ECH it was not possible to exactly identify a group of women similar to ELBU respondents (which basically correspond to the mother of the reference child), we restricted in both cases the sample to women aged 55 years or less, as in the baseline they had to be mothers of children aged 6–7 years old. ECH and ELBU show very similar results, in terms of average years of education among adults and crowding. Per capita household income is 30% lower in ELBU compared to the equivalent ECH population. However, it can also be noticed that average labour earnings results are very similar in the two surveys. At the same time, employment rates among respondents are very similar, and even higher at ELBU. Average age among potential respondents are very similar in the two cases.

Hence, differences in per capita household income among the two surveys cannot be attributed to labour earnings or employment rates. This suggests that non labour income explains the gap, and, probably, this is relate to the fact that ECH has a larger set of questions assessing capital income and contributory and non contributory transfers.

Finally, comparing the whole ELBU baseline indicators and those restricted to the balanced panel, it can be noticed that the indicators are almost the same, suggesting that panel attrition did not have a significant effect on observable variables.

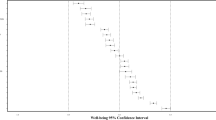

Annex 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salas, G., Vigorito, A. Subjective Well-Being and Adaptation. The Case of Uruguay. Applied Research Quality Life 14, 685–703 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9616-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9616-1