Abstract

We conducted a household survey among 6061 adults in Lesotho to (1) assess the prevalence of moderate/severe mental health (MH) and substance use (SU) problems (2) describe the MH and SU service cascades, and (3) assess predictors of MH and SU problem awareness (i.e., awareness of having a MH/SU problem that requires treatment). Moderate/severe MH or SU problems was reported between 0.7% for anxiety in the past 2 weeks to 36.4% for alcohol use in the past 3 months. The awareness and treatment gaps were high for both MH (62% awareness gap; 82% treatment gap) and SU (89% awareness gap; 95% treatment gap). Individuals with higher than the median household wealth had lower MH and SU problem awareness and those living in urban settings had greater SU problem awareness. Research should investigate how to increase population awareness of MH/SU problems to reduce the burden of these conditions in this setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The World Health Organization (WHO) conceptualizes mental health (MH) as a state of well-being in which an individual realizes their own abilities, can cope with the normal stressors of life, and is able to work productively and contribute to their community. MH problems, such as depression, anxiety, or suicidality, involve significant disturbances in thinking, emotion regulation, or behavior and can change at any point across the lifespan (Chekroud et al., 2017; Galderisi et al., 2017). Substance use (SU) involves the recreational, experimental, or therapeutic consumption of substances, including legal or illegal drugs, alcohol, or medications. Problematic SU results in negative individual or interpersonal health or social consequences (Horowitz & Taylor, 2023).

MH and SU problems have increased globally and are recognized as major barriers to achieving the health-for-all goals laid out in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Frankish et al., 2018; Sustainable Development Goal 3. United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs, 2023). In 2019, there was an estimated 970 million people with MH and SU disorders globally, representing a 48% increase in these disorders from 1990. The proportion of global disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) attributed to MH and SU disorders also increased from 3.1% to 4.9% in the same period (GBD, 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022).

At the same time, a large gap exists between those who need MH and SU services and those who have access to, and make use of, such services. It is estimated that only 1% of the global health workforce provides mental health care, a contributing factor to the estimated 75% to 95% of people who need care for these conditions but do not receive services (Freeman, 2022; GBD, 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022; Jack et al., 2014). The high prevalence of MH/SU problems combined with the unmet need for services are the main contributors of the increasing proportion of global DALYs attributed to these conditions (GBD, 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022).

The risks for MH and SU problems, such as rapid urbanization, poverty, or conflict, have been well described in sub-Saharan Africa, (Gbadamosi et al., 2022; Onaolapo et al., 2022; Sadanand et al., 2021). It is therefore necessary to ensure that factors associated with health service seeking behavior are also understood. Access to quality MH services presents a complex picture influenced by both supply-side factors, including health infrastructure, availability of trained professionals, and sufficient funding to build responsive services, as well as demand-side factors, which include service user awareness and knowledge about MH, perceived benefits of treatment, trust in the system, and ability to pay for out of pocket expenses (Aguwa et al., 2023; Bakibinga et al., 2022; van den Broek et al., 2023). The World Mental Health Survey Initiative developed a standardized tool to measure awareness of the need for MH services as well as the type of services accessed. Across multiple studies, included low resource settings and African settings, awareness of need for care for MH and SU ranged from 39 to 41% and access to adequate services ranged from 22 to 29% (Alonso et al., 2018; Degenhardt et al., 2017; Harris et al., 2020). However, there is no data on these demand-side factors from Lesotho, which is critical to expand services in this setting.

Lesotho, a landlocked country within Southern Africa, has a historically heavy burden of infectious diseases, such as HIV and tuberculosis, and a growing burden of non-communicable diseases (Gouda et al., 2019; Lesotho TB Dashboard, 2023; UNAIDS Lesotho, 2023). Data collected over 30 years ago, suggested that major depression and generalized anxiety were common both in the community (12.4% and 6.2%) and in general outpatient setting (21.7% and 27.9%), respectively (Hollifield et al., 1990, 1994). Newer estimates using data collected from small samples of people living with HIV, youth, and pregnant women highlight that trauma, sexual and interpersonal violence, and unhealthy alcohol use are of growing concern (Cerutti et al., 2016; Lesotho Violence Against Children and Youth Survey, 2020; Marlow et al., 2021; Meursing & Morojele, 1989; Siegfried et al., 2001) although these data are not necessarily representative of the population. Furthermore, estimates and predictors of the MH and SU problem health service gaps have not been evaluated at the population level, but are important for policymakers.

Thus, the overall goal of this study was to examine, in adults living in two primarily rural districts in Lesotho: (1) the prevalence of moderate/severe MH and SU problems using validated questionnaires, (2) the MH and SU problem service cascades, and (3) predictors of MH and SU problem awareness (i.e., awareness of having a MH/SU problem that requires treatment).

Methods

Setting

This study forms part of a PhD thesis within the Community-based Chronic Care Lesotho Project (ComBaCaL; www.combacal.org). The first part of this project included a large population-based, cross-sectional survey assessing different non-communicable diseases among individuals living in the Butha-Buthe and Mokhotlong districts in Northern Lesotho. In addition to MH, this study collected data on cardiovascular risk factors, lifestyle behaviors, household wealth, hepatitis B and HIV infection, and cardiovascular disease complications. A detailed description of the setting and methods can be found elsewhere (González Fernández et al., 2023). Data were collected between November 2021 to August 2022. The estimated combined population of the two districts is 250,000 people and includes predominantly subsistence farmers, mine workers, as well as construction and domestic laborers who work in neighboring South Africa. Each district has one central mid-size town, Butha-Buthe with ca. 25,000 inhabitants and Mokhotlong with ca. 10,000 inhabitants. The remaining population lives in rural villages scattered over a mountainous area of 5,842 km2.

The available health services are provided through 22 health facilities. Butha-Buthe has ten nurse-led rural health centers, one missionary hospital, and one governmental hospital. In Mokhotlong, there are nine nurse-led rural health centers and one governmental hospital (United Nations Development program, 2019). The MH and SU services in the country are scarce, with one psychiatric hospital near the capital city as well as short-term observation units at district hospitals for individuals with acute psychiatric distress. MH and SU outpatient services are staffed by one to two psychiatric nurses at each district hospital. These providers are responsible for the MH and SU services of the entire district. Limited services are available in the private sector (mostly in the capital city, when available) and routine data is scant (Mental Health Atlas: Lesotho, 2014).

Participants

We randomly sampled 120 population clusters (60 urban/peri-urban clusters and 60 rural clusters) across the two districts. We considered the clusters as primary sampling units and household members as secondary sampling units. A household was defined as one or more individuals who resided in a physical structure (e.g., compound, homestead) and shared housekeeping arrangements. A household member was defined as any individual who was acknowledged by the head of household as such. All household members of all ages, both absent and present, were enumerated. Households were eligible if the household head, or an adult representative, gave verbal consent. Household members were randomly selected by an algorithm considering age, sex and settlement (urban vs rural), programmed in the Open Data Kit (ODK) data collection software (Open Data Kit, 2023). Selected household members were eligible if they provided written informed consent.

Field Procedures

A study team was most often composed of eight members and included nurses, nursing assistants, and lay health workers. After arriving at a cluster, the team sought oral approval from the village chief, and thereafter started visiting the households. Upon consent from the household head, the team collected sex and age information of all present and absent household members. Only present household members were eligible for the study. If a present household member was randomly selected by the algorithm and provided written informed consent, the study team proceeded to collect data. All data were collected during the COVID-19 epidemic from adults who were available in the household at the time of arrival of the study team, mostly during working days and business hours. Respondents who were not present in the household (workers, migrants, younger people) or were institutionalized (prison, hospital) were not invited to participate. The study team only went to each household once. Survey participants received study information in Sesotho, the local language, and provided written informed consent. Trained study staff collected data using the ODK platform, administered the questionnaires, and collected responses from participants in English or Sesotho using in-person interviews. All MH and SU questionnaires underwent a standardized translation and back-translation process.

Measurements

Demographics

Information was collected at the household and individual level. Household information included geographic coordinates and socioeconomic status using the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) Program wealth index questions for Lesotho. The DHS wealth index is calculated based on a questionnaire that assesses housing construction characteristics, household assets and utility services, including country-specific assets that are viewed as indicators of economic status (USAID, 2014). Individual demographics included gender, age, highest level of education completed, employment in the past 12 months, relationship status, comorbidities, and pregnancy status for women.

Depression and Suicidal Ideation

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) assesses symptoms of major depression over the last two weeks. There are a total of 9 items, with each item scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). Suicidal thinking was measured using the final item of the PHQ-9 that asks about thoughts being better off dead or of hurting oneself in some way. Depressive symptoms were categorized following the standardized cut-offs of the instrument: “none/minimal risk” (score 0–4), “low risk” (5–9), and “moderate to high risk” (10–27). The reliability, validity and cross-cultural relevance or this screening instrument was assessed by Sweetland et al., and this questionnaire has been validated for use in similar cultural and linguistic settings (Cholera et al., 2014; Gelaye et al., 2013, 2016; Sweetland et al., 2014). Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.91.

Anxiety

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire is a 7-item scale assessing the symptoms of anxiety. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). Similar to PHQ-9, this tool uses standardized symptom severity categorizations of “none/minimal risk” (0–4), “low risk” (5–9), and “moderate to high risk” (10–21). The psychometric characteristics of this tool in the region have been evaluated by different authors and the tool has been extensively used to evaluate anxiety symptoms in similar settings (Manzar et al., 2021; Nyongesa et al., 2020; Sweetland et al., 2014). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.89.

Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress

The Primary Care Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder screener (PC-PTSD-5) is a validated questionnaire that was used to assess the presence of lifetime trauma and subsequent symptoms of posttraumatic stress (Mughal et al., 2020; Prins et al., 2016; Spottswood et al., 2017). Participants who reported a traumatic event were screened for five hallmark symptoms of PTSD. A score of ≥ 3 indicates possible PTSD (Prins et al., 2016). The type of traumatic events experienced in the sample were categorized based on previously reported trauma episode type (Kessler et al., 2017). This tool had demonstrated good psychometric properties, including internal consistency and construct validity in the sub-Saharan region (Girma et al., 2022; Verhey et al., 2018). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.52.

Alcohol and Other SU

The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) questionnaire is a World Health Organization (WHO)-developed assessment tool for unhealthy alcohol or other drug use in adults. ASSIST explores the use of ten substances: tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens, opioids, and other drugs. Our study examined all substances except for tobacco. A risk score is provided for each substance and scores are grouped into 'low risk' (score < 11 for alcohol and < 4 for other substances), 'moderate risk,' (score between 11–26 for alcohol, and 4–26 for all other substances), or 'high risk' (score ≥ 27 for all substances). The ASSIST cut-off scores have shown reliable sensitivity and specificity, particularly when distinguishing between substance use and abuse. There is strong internal validity evidence from previous studies in the region, as this questionnaire has been widely used in clinical practice and research settings across Africa (van der Westhuizen et al., 2016) The Cronbach’s alpha index calculated on those who consumed alcohol in the past 3 months was 0.80 and 0.54 for those who consumed cannabis.

MH and SU problem awareness and service access

These constructs were evaluated using a questionnaire adapted from the World Mental Health Surveys (Alonso et al., 2018). Participants who reported at least moderate MH or SU symptoms on any questionnaire or who reported any suicidal thoughts were asked first, whether they felt they needed treatment for their reported symptoms/behaviors (“problem awareness”), second, whether they had accessed services within the past 12 months (“treatment access”), third, who provided the care (professional service provider versus lay person; “professional treatment access”), and fourth, what treatment was received. Affirmative responses to the first two steps were assigned a value of 1 and negative responses were assigned a value of 0.

Services provider options were conceptualized broadly and response options were as follows: specialized/general medical (psychiatric nurse, social worker, doctor, or nurse), complementary alternative medical (traditional healer), non-medical professional (religious or spiritual advisor), trained lay health worker (village health worker, lay counsellor, or similar), support provided by a close friend or family member (non-trained), and support provided by other community member (non-trained). Response options for services received were as follows: medication, talk therapy, or other.

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were summarized as frequency or median with interquartile range (IQR). We calculated prevalence and 95% Wald confidence intervals (CIs) for moderate/severe problems with depression, anxiety, PTSD, alcohol, and cannabis use, as well as any suicidal ideation.

Descriptives (frequencies and percentages) were calculated for each step of the care cascade for both MH and SU, where we included participants who had information across all steps of the cascade. To examine predictors of individuals who perceived a need for treatment of their MH and SU problems (“problem awareness” step of the cascade), we conducted univariable and multivariable logistic regression models using odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs. Predictors included sex, age, relationship status, income, settlement (peri-urban/rural), reported HIV infection, and household wealth. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata (version 16.1, College Station, Tex: StataCorp LP, 2007).

Results

In the 120 clusters, the teams visited 3485 households with 6061 consenting adult participants who were 18 years or older. Complete data were available for almost all participants for MH and SU outcomes (≥ 99% complete data for each MH/SU problem). The study flow and data completeness are presented in Fig. 1. Table 1 provides the overall demographic and clinical characteristics of all consenting study participants, as well as by participant sex. A total of 52.2% (3164/6061) were females. Half of all participants lived in urban or peri-urban settings. The median age of participants was 39 years (IQR 27–58 years). Most were married or in a stable relationship (58.5%) and had obtained at least primary school education (89.9%). Just under half the sample (48.9%) did not have a source of regular income, with the majority being women (2132/2962). Regarding comorbidities, a total of 15.2% (924/6061) of participants reported to be living with HIV, 21.6% (1308/6061) had hypertension, and 4.8% (291/6061) had diabetes.

Flow chart of all included participants. aLesotho—Subnational Population Statistics-UNFPA: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ps-lso. bHad no participants who were eligible for survey. cIndividuals were enumerated but not present at the time of the survey or were not eligible. Acronyms: PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7: The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 questionnaire, PC-PTSD-5. The Primary Care Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder screener, ASSIST: The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test

Prevalence of MH and SU Symptoms

Among the 6061 total study participants, a total of 367 (6.0%) and 768 (12.7%) reported moderate/severe MH or SU problems, respectively, and 7.2% (95% CI 6.6–7.9, 438/6061) reported problems related to two or more measured conditions. The prevalence estimates of each MH and SU problem are presented in Table 2, disaggregated by sex, settlement (urban vs rural), and self-reported HIV status. Using a cutoff score of ≥ 10, 1.6% (95% CI 1.4—2.1; 98/6042) and 0.7% (95% CI 0.5–0.9%; 43/6048) of the sample reported moderate/severe depression and anxiety problems, respectively. Suicidal thoughts were reported by 0.8% (95% CI 0.6–1.1%; 47/6042) of participants. A total of 18.5% (1121/6054) of participants reported at least one traumatic experience in their lifetime, with an average of 1.21 events per person with a trauma history. The most frequent event reported was related to the unexpected death of a loved one (40.2%), followed by life threatening accident (21.7%), witnessing trauma in others (12.6%), or being victims of physical violence (10.9%) (see Supplementary Table 1). Overall, 4.2% (95% CI 3.6–4.7%; 252/6054) of the entire sample screened positive for possible PTSD.

In relation to SU problems, alcohol was the most commonly used substance, with 26.1% (1579/6047) of participants reporting consumption in the previous three months and 44.8% (707/1579) of those participants reporting weekly or daily use of alcohol. Among the participants who reported alcohol use in the previous three months, 36.4% (95% CI 33.9–38.6%; 572/1579) scored as moderate/high risk users, of which 81.6% (95% CI 78.5–84.8%; 467/572) were men. With regards to other substances, cannabis was the second most commonly reported substance used, with 4.4% (267/6047) reporting lifetime consumption and 4.1% (248/6047) in the previous three months. Of those who used cannabis in the previous three months, 93.5% (95% CI 90.5–96.6%; 232/248) scored as moderate/high risk users, of which almost all were men (98.7%; 95% CI 97.3–100.0%, 229/232). Use of all other drugs was very scarcely reported in this population (Supplementary Table 2).

MH and SU Care Cascades

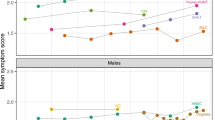

Figure 2 displays the MH and SU cascades and unmet gap for individuals who had moderate or severe MH or SU problems. A total of 367 and 768 participants with full information were included in the MH and SU cascades, respectively. In the MH cascade, 37.9% (139/367) of participants felt they needed treatment for their MH problem (“problem awareness”), 18.5% (68/367) had accessed any kind of care in the previous 12 months (“treatment access”), and 9.2% (34/367) had obtained services for their MH problem from a specialized health worker (“professional treatment access”). In the SU cascade, problem awareness was 10.9% (84/768), treatment access was 4.9% (38/768), and professional treatment access was only 3.9% (20/768). For those accessing treatment from the non-professional workforce, about 50% did so from a variety of paraprofessional and non-specialized provider types, including traditional healers, religious or spiritual advisors, village health workers, lay counsellors, friends, family members, and other community members.

Risk Factors Associated with MH and SU Problem Awareness

Table 3 shows the sociodemographic factors associated with participants reporting moderate or severe MH or SU problems who felt they needed treatment for their MH or SU problem (i.e., had MH or SU problem awareness). In the multivariate models, having household wealth in the fourth quintile was associated with lower odds of awareness in both the MH and SU treatment cascades, as compared to those with median household wealth (MH problem awareness: aOR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.22—0.93; SU problem awareness: aOR = 0.37, 95% CI 0.17—0.79). Additionally, settlement type was associated with SU problem awareness, such that participants living in urban settings had higher odds of recognizing the need for SU treatment (aOR = 2.53, 95% CI 1.44–4.44), as compared to their rural counterparts.

Discussion

This study reports on community-based prevalence data of several MH and SU problems in adults living in two primarily rural districts in Lesotho. Approximately 6% and 13% of the sample reported moderate/severe MH and SU symptoms, respectively. The most frequently reported MH problem was symptoms consistent with PTSD, whereas excessive alcohol use emerged as the most frequent SU problem. Most individuals who had moderate/severe MH or SU symptoms were unaware of the need for treatment and only a minority of those needing treatment had accessed needed services.

Moderate/severe symptoms of depression and anxiety were reported by approximately 2% and 1% of the participants, respectively. Lifetime rates of trauma were reported in about one in five participants, with just over 4% of the sample having probable PTSD. Our study found lower rates of most measured MH problems, compared to other studies or estimates in the region (Gbadamosi et al., 2022; Kessler et al., 2017; Mars et al., 2014; Ng et al., 2020; Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya, 2013). One potential explanation is that these data were collected as part of a large survey focused on multiple non-communicable conditions, which included many questionnaires and biological measurements. It is possible that these extensive survey procedures did not create an adequate environment to collect sensitive information from study participants. Future research may benefit from ensuring dedicated time and space to collect MH data, which may need to involve separate research visits.

Although our study found that alcohol was more frequently consumed by men than women, of the individuals who consumed any alcohol, almost 30% of women and 40% of men had moderate/severe problems. This suggests that when alcohol is consumed, there is a relatively high likelihood that alcohol is consumed in an unhealthy way by both men and women. The recognition that alcohol use is under-detected in women has been described previously (Martinez et al., 2011). Our study especially highlights the importance of harmful drinking found in women, which extends prior research in Lesotho that focused mainly on heavy episodic drinking and generally found lower rates of problem drinking in women (Mahlomaholo et al., 2021). Integrating a validated alcohol consumption risk screening tool in routine health care, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Morojele et al., 2017), would potentially find most-at-risk men and women who would likely benefit from alcohol reduction interventions.

A second major finding of this study is the unmet need of receiving services among those reporting MH and/or SU problems. The MH and SU treatment gap has typically been framed as a result of shortages on the supply side (i.e., services are unavailable), rather than on the demand side (Roberts et al., 2022). However, in the last few years, there has been increased attention on the demand side as a major contributor to the existing treatment gap in low resource settings. The World Mental Health Surveys (Andrade et al., 2014) found that the lack of perceived need for treatment has been, by far, the most frequent reason for not seeking MH and SU services globally, with a stronger effect on seeking SU services (Nadkarni et al., 2022). The PRIME program in India, for example, demonstrated that in the absence of demand, increasing the supply of MH services was not enough to reduce the treatment gap for common mental disorders (Shidhaye et al., 2019), and comparable data is becoming available within the sub-Saharan region (Abdulmalik et al., 2019; Bakibinga et al., 2022; Nicholas et al., 2022).

Our results show that approximately 38% of participants with moderate/severe MH problems and 11% with moderate/high risk SU problems had the perception that they needed treatment for their symptoms. Participants whose household wealth was in the fourth quintile (compared to the median household wealth group) had lower odds of recognizing a MH or SU problem, whereas participants living in urban settings had greater odds of recognizing their SU problem required treatment. Individuals living in more urban settings are more likely to be exposed to SU treatment information as well as other individuals with SU problems (Muthelo et al., 2023; Myers et al., 2010; Ngene et al., 2023; Nicholas et al., 2022), which may help them gain more insight into their own level of SU problems. The results of this observational study suggest that an important step in addressing the MH and SU treatment gaps is to improve awareness and motivation for treatment. This could be addressed by incorporating motivational interviewing approaches in the context of brief interventions at existing health facilities, where individuals receive other health services (Gaynes et al., 2021; Harder et al., 2020; Sorsdahl et al., 2015). Findings from this study also suggest that participants receive MH and SU services from a wide range of both professional and paraprofessional/lay providers, suggesting that scaling up of MH and SU service provision should capitalize on the entire range of provider types to increase access and acceptability of care options (Adepoju, 2020; Burns & Tomita, 2015; Charlson et al., 2014; Galvin & Byansi, 2020; Satinsky et al., 2021).

There are several strengths and limitations to consider when interpreting study findings. One strength was that the study design allowed data collection from a set of randomly selected clusters and therefore provided representative community-based estimates. However, respondents who were not present in the household at the time of the study team visit (e.g., workers, migrants, younger people) or who were institutionalized (prison, hospital), were not included. Another important limitation was that, despite the use of validated MH and SU questionnaires, we did not conduct diagnostic interviews, which may obscure the true underlying rates of MH and SU problems and the real need for treatment services (Ali et al., 2016; Belus et al., 2022; Haroz et al., 2017; Michalopoulos et al., 2020). In addition, the frequency of reporting symptoms could also be affected by recall bias, and especially by the societal and individual stigma associated with MH and SU problems (Alemu et al., 2023). Further research could shed light to better describing the prevalence and distribution of MH and SU problems across different population groups, provide cultural adaptation of assessment tools, and increase knowledge about mental health literacy and barriers to care in this setting. Lastly, although we cannot ascertain the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on data collection and study findings, the implementation of the study was more challenging during COVID-19 restrictions. A follow-up study conducted in a few years’ time would be warranted to investigate whether the rates of MH and SU problems remain consistent.

Conclusion

This is the first study to quantify and describe the distribution of MH and SU problems at the population level in Lesotho in two primarily rural districts. We found a lower prevalence of moderate and severe MH and SU problems than reported in other studies from sub-Saharan Africa, suggesting that culturally informed assessment tools for MH and SU services may be needed in Lesotho. Nonetheless, we still observed significant gaps throughout the treatment cascades for both MH and SU, particularly regarding awareness and service access. More efforts are likely needed to increase the demand side of MH and SU services in Lesotho to substantially reduce these treatment gaps.

Data Availability

If the manuscript is accepted, we will deposit an anonymized dataset with key data presented in the manuscript on zenodo.org.

References

Abdulmalik, J., Olayiwola, S., Docrat, S., Lund, C., Chisholm, D., & Gureje, O. (2019). Sustainable financing mechanisms for strengthening mental health systems in Nigeria. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0293-8

Adepoju, P. (2020). Africa turns to telemedicine to close mental health gap. The Lancet Digital Health, 2(11), e571–e572. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30252-1

Aguwa, C., Carrasco, T., Odongo, N., & Riblet, N. (2023). Barriers to Treatment as a Hindrance to Health and Wellbeing of Individuals with Mental Illnesses in Africa: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(4), 2354–2370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00726-5

Alemu, W. G., Due, C., Muir-Cochrane, E., Mwanri, L., & Ziersch, A. (2023). Internalised stigma among people with mental illness in Africa, pooled effect estimates and subgroup analysis on each domain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 23, 480. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04950-2

Ali, G.-C., Ryan, G., & De Silva, M. J. (2016). Validated Screening Tools for Common Mental Disorders in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE, 11(6), e0156939. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156939

Alonso, J., Liu, Z., Evans-Lacko, S., Sadikova, E., Sampson, N., Chatterji, S., Abdulmalik, J., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Andrade, L. H., Bruffaerts, R., Cardoso, G., Cia, A., Florescu, S., de Girolamo, G., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., He, Y., de Jonge, P., …, WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators. (2018). Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: Results of the World Mental Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depression and Anxiety, 35(3), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22711

Andrade, L. H., Alonso, J., Mneimneh, Z., Wells, J. E., Al-Hamzawi, A., Borges, G., Bromet, E., Bruffaerts, R., de Girolamo, G., de Graaf, R., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Hinkov, H. R., Hu, C., Huang, Y., Hwang, I., Jin, R., Karam, E. G., Kovess-Masfety, V., …, Kessler, R. C. (2014). Barriers to Mental Health Treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 44(6), 1303–1317. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713001943

Bakibinga, P., Kisia, L., Atela, M., Kibe, P. M., Kabaria, C., Kisiangani, I., & Kyobutungi, C. (2022). Demand and supply-side barriers and opportunities to enhance access to healthcare for urban poor populations in Kenya: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 12(5), e057484. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057484

Belus, J. M., Muanido, A., Cumbe, V. F. J., Manaca, M. N., & Wagenaar, B. H. (2022). Psychometric Validation of a Combined Assessment for Anxiety and Depression in Primary Care in Mozambique (CAD-MZ). Assessment, 29(8), 1890–1900. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911211032285

Burns, J. K., & Tomita, A. (2015). Traditional and religious healers in the pathway to care for people with mental disorders in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(6), 867–877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0989-7

Cerutti, B., Broers, B., Masetsibi, M., Faturiyele, O., Toti-Mokoteli, L., Motlatsi, M., Bader, J., Klimkait, T., & Labhardt, N. D. (2016). Alcohol use and depression: Link with adherence and viral suppression in adult patients on antiretroviral therapy in rural Lesotho, Southern Africa: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 947. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3209-4

Charlson, F. J., Diminic, S., Lund, C., Degenhardt, L., & Whiteford, H. A. (2014). Mental and substance use disorders in Sub-Saharan Africa: Predictions of epidemiological changes and mental health workforce requirements for the next 40 years. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e110208. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110208

Chekroud, A. M., Loho, H., & Krystal, J. H. (2017). Mental illness and mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(4), 276–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30088-3

Cholera, R., Gaynes, B. N., Pence, B. W., Bassett, J., Qangule, N., Macphail, C., Bernhardt, S., Pettifor, A., & Miller, W. C. (2014). Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in a high-HIV burden primary healthcare clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of Affective Disorders, 167, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.003

Degenhardt, L., Glantz, M., Evans-Lacko, S., Sadikova, E., Sampson, N., Thornicroft, G., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Helena Andrade, L., Bruffaerts, R., Bunting, B., Bromet, E. J., Miguel Caldas de Almeida, J., de Girolamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Maria Haro, J., Huang, Y., …, Collaborators, on behalf of the W. H. O. W. M. H. S. (2017). Estimating treatment coverage for people with substance use disorders: An analysis of data from the World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20457

Frankish, H., Boyce, N., & Horton, R. (2018). Mental health for all: A global goal. The Lancet, 392(10157), 1493–1494. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32271-2

Freeman, M. (2022). Investing for population mental health in low and middle income countries—Where and why? International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 16(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-022-00547-6

Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., & Sartorius, N. (2017). A proposed new definition of mental health. Psychiatria Polska, 51(3), 407–411. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/74145

Galvin, M., & Byansi, W. (2020). A systematic review of task shifting for mental health in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Mental Health, 49(4), 336–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2020.1798720

Gaynes, B. N., Akiba, C. F., Hosseinipour, M. C., Kulisewa, K., Amberbir, A., Udedi, M., Zimba, C. C., Masiye, J. K., Crampin, M., Amarreh, I., & Pence, B. W. (2021). The sub-Saharan Africa Regional Partnership for Mental Health Capacity Building (SHARP) Scale-up Trial: Study Design and Protocol. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 72(7), 812–821. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000003

Gbadamosi, I. T., Henneh, I. T., Aluko, O. M., Yawson, E. O., Fokoua, A. R., Koomson, A., Torbi, J., Olorunnado, S. E., Lewu, F. S., Yusha’u, Y., Keji-Taofik, S. T., Biney, R. P., & Tagoe, T. A. (2022). Depression in Sub-Saharan Africa. IBRO Neuroscience Reports, 12, 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibneur.2022.03.005

GBD, 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3

Gelaye, B., Williams, M. A., Lemma, S., Deyessa, N., Bahretibeb, Y., Shibre, T., Wondimagegn, D., Lemenhe, A., Fann, J. R., Vander Stoep, A., & Andrew Zhou, X.-H. (2013). Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for depression screening and diagnosis in East Africa. Psychiatry Research, 210(2), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.015

Gelaye, B., Wilson, I., Berhane, H. Y., Deyessa, N., Bahretibeb, Y., Wondimagegn, D., Shibre Kelkile, T., Berhane, Y., Fann, J. R., & Williams, M. A. (2016). Diagnostic validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) among Ethiopian adults. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 70, 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.07.011

Girma, E., Ametaj, A., Alemayehu, M., Milkias, B., Yared, M., Misra, S., Stevenson, A., Koenen, K. C., Gelaye, B., & Teferra, S. (2022). Measuring traumatic experiences in a sample of Ethiopian adults: Psychometric properties of the life events checklist-5. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6(4), 100298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2022.100298

González Fernández, L., Firima, E., Gupta, R., Sematle, M. P., Khomolishoele, M., Molulela, M., Bane, M., Meli, R., Tlahali, M., Lee, T., Chammartin, F., Gerber, F., Lejone, T. I., Ayakaka, I., Weisser, M., Amstutz, A., & Labhardt, N. D. (2023). Prevalence and determinants of cardiovascular risk factors in Lesotho: A population-based survey. International Health, ihad058. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihad058

Gouda, H. N., Charlson, F., Sorsdahl, K., Ahmadzada, S., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H., Leung, J., Santamauro, D., Lund, C., Aminde, L. N., Mayosi, B. M., Kengne, A. P., Harris, M., Achoki, T., Wiysonge, C. S., Stein, D. J., & Whiteford, H. (2019). Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Global Health, 7(10), e1375–e1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30374-2

Harder, V. S., Musau, A. M., Musyimi, C. W., Ndetei, D. M., & Mutiso, V. N. (2020). A Randomized Clinical Trial of Mobile Phone Motivational Interviewing for Alcohol Use Problems in Kenya. Addiction (abingdon, England), 115(6), 1050–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14903

Haroz, E. E., Ritchey, M., Bass, J. K., Kohrt, B. A., Augustinavicius, J., Michalopoulos, L., Burkey, M. D., & Bolton, P. (2017). How is depression experienced around the world? A systematic review of qualitative literature. Social Science & Medicine, 1982(183), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.030

Harris, M. G., Kazdin, A. E., Chiu, W. T., Sampson, N. A., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Altwaijri, Y., Andrade, L. H., Cardoso, G., Cía, A., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Hu, C., Karam, E. G., Karam, G., Mneimneh, Z., Navarro-Mateu, F., Oladeji, B. D., …, for the WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators. (2020). Findings From World Mental Health Surveys of the Perceived Helpfulness of Treatment for Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(8), 830–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1107

Hollifield, M., Katon, W., Spain, D., & Pule, L. (1990). Anxiety and depression in a village in Lesotho, Africa: A comparison with the United States. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 156, 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.156.3.343

Hollifield, M., Katon, W., & Morojele, N. (1994). Anxiety and Depression in an Outpatient Clinic in Lesotho, Africa. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 24(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.2190/X3XA-LPJB-C3KW-AMLY

Horowitz, M. A., & Taylor, D. (2023). Addiction and physical dependence are not the same thing. The Lancet Psychiatry, 10(8), e23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00230-4

Jack, H., Wagner, R. G., Petersen, I., Thom, R., Newton, C. R., Stein, A., Kahn, K., Tollman, S., & Hofman, K. J. (2014). Closing the mental health treatment gap in South Africa: A review of costs and cost-effectiveness. Global Health Action, 7(1), 23431. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23431

Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., Degenhardt, L., de Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R. V., Ferry, F., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., Lepine, J.-P., Levinson, D., …, Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383

Lesotho TB Dashboard. (2023). LESOTHO TB Dashboard. https://www.stoptb.org/static_pages/LSO_Dashboard.html

Lesotho Violence Against Children and Youth Survey. (2020). Lesotho Violence Against Children and Youth Survey. https://www.togetherforgirls.org/en/resources/lesotho-vacs-report-2020

Mahlomaholo, P. M., Wang, H., Xia, Y., Wang, Y., Yang, X., & Wang, Y. (2021). Depression and Suicidal Behaviors Among HIV-Infected Inmates in Lesotho: Prevalence, Associated Factors and a Moderated Mediation Model. AIDS and Behavior, 25(10), 3255–3266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03330-9

Manzar, M. D., Alghadir, A. H., Anwer, S., Alqahtani, M., Salahuddin, M., Addo, H. A., Jifar, W. W., & Alasmee, N. A. (2021). Psychometric Properties of the General Anxiety Disorders-7 Scale Using Categorical Data Methods: A Study in a Sample of University Attending Ethiopian Young Adults</p>. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 17, 893–903. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S295912

Marlow, M., Christie, H., Skeen, S., Rabie, S., Louw, J. G., Swartz, L., Mofokeng, S., Makhetha, M., & Tomlinson, M. (2021). Alcohol use during pregnancy in rural Lesotho: “There is nothing else except alcohol.” Social Science & Medicine, 291, 114482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114482

Mars, B., Burrows, S., Hjelmeland, H., & Gunnell, D. (2014). Suicidal behaviour across the African continent: A review of the literature. BMC Public Health, 14, 606. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-606

Martinez, P., Røislien, J., Naidoo, N., & Clausen, T. (2011). Alcohol abstinence and drinking among African women: Data from the World Health Surveys. BMC Public Health, 11, 160. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-160

Mental Health Atlas: Lesotho. (2014). https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/mental-health-atlas-2014-country-profile-lesotho

Meursing, K., & Morojele, N. (1989). Use of alcohol among high school students in Lesotho. British Journal of Addiction, 84(11), 1337–1342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00735.x

Michalopoulos, L. M., Meinhart, M., Yung, J., Barton, S. M., Wang, X., Chakrabarti, U., Ritchey, M., Haroz, E., Joseph, N., Bass, J., & Bolton, P. (2020). Global posttrauma symptoms: A systematic review of qualitative literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(2), 406–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018772293

Morojele, N. K., Nkosi, S., Kekwaletswe, C. T., Shuper, P. A., Manda, S. O., Myers, B., & Parry, C. D. H. (2017). Utility of Brief Versions of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) to Identify Excessive Drinking Among Patients in HIV Care in South Africa. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2017.78.88

Mughal, A. Y., Devadas, J., Ardman, E., Levis, B., Go, V. F., & Gaynes, B. N. (2020). A systematic review of validated screening tools for anxiety disorders and PTSD in low to middle income countries. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 338. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02753-3

Muthelo, L., Mbombi, M. O., Mphekgwana, P., Mabila, L. N., Dhau, I., Tlouyamma, J., Nemuramba, R., Mashaba, R. G., Mothapo, K., Ntimana, C. B., & Maimela, E. (2023). Exploring Roles of Stakeholders in Combating Substance Abuse in the DIMAMO Surveillance Site, South Africa. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 11782218221147498. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218221147498

Myers, B. J., Louw, J., & Pasche, S. C. (2010). Inequitable access to substance abuse treatment services in Cape Town, South Africa. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 5(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-5-28

Nadkarni, A., Bhatia, U., Bedendo, A., de Paula, T. C. S., de Andrade Tostes, J. G., Segura-Garcia, L., Tiburcio, M., & Andréasson, S. (2022). Brief interventions for alcohol use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: Barriers and potential solutions. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 16(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-022-00548-5

Ng, L. C., Stevenson, A., Kalapurakkel, S. S., Hanlon, C., Seedat, S., Harerimana, B., Chiliza, B., & Koenen, K. C. (2020). National and regional prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 17(5), e1003090. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003090

Ngene, N. C., Khaliq, O. P., & Moodley, J. (2023). Inequality in health care services in urban and rural settings in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 27(5s), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2023/v27i5s.11

Nicholas, A., Joshua, O., & Elizabeth, O. (2022). Accessing Mental Health Services in Africa: Current state, efforts, challenges and recommendation. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 81, 104421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104421

Nyongesa, M. K., Mwangi, P., Koot, H. M., Cuijpers, P., Newton, C. R. J. C., & Abubakar, A. (2020). The reliability, validity and factorial structure of the Swahili version of the 7-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) among adults living with HIV from Kilifi Kenya. Annals of General Psychiatry, 19, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-020-00312-4

Onaolapo, O. J., Olofinnade, A. T., Ojo, F. O., Adeleye, O., Falade, J., & Onaolapo, A. Y. (2022). Substance use and substance use disorders in Africa: An epidemiological approach to the review of existing literature. World Journal of Psychiatry, 12(10), 1268–1286. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i10.1268

Open Data Kit. (2023). https://opendatakit.org/

Peltzer, K., & Phaswana-Mafuya, N. (2013). Depression and associated factors in older adults in South Africa. Global Health Action, 6, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.18871

Prins, A., Bovin, M. J., Smolenski, D. J., Marx, B. P., Kimerling, R., Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Kaloupek, D. G., Schnurr, P. P., Kaiser, A. P., Leyva, Y. E., & Tiet, Q. Q. (2016). The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and Evaluation Within a Veteran Primary Care Sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(10), 1206–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5

Roberts, T., Esponda, G. M., Torre, C., Pillai, P., Cohen, A., & Burgess, R. A. (2022). Reconceptualising the treatment gap for common mental disorders: A fork in the road for global mental health? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 221(3), 553–557. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.221

Sadanand, A., Rangiah, S., & Chetty, R. (2021). Demographic profile of patients and risk factors associated with suicidal behaviour in a South African district hospital. South African Family Practice, 63(1), 5330. https://doi.org/10.4102/safp.v63i1.5330

Satinsky, E. N., Kleinman, M. B., Tralka, H. M., Jack, H. E., Myers, B., & Magidson, J. F. (2021). Peer-delivered services for substance use in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. International Journal of Drug Policy, 95, 103252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103252

Shidhaye, R., Baron, E., Murhar, V., Rathod, S., Khan, A., Singh, A., Shrivastava, S., Muke, S., Shrivastava, R., Lund, C., & Patel, V. (2019). Community, facility and individual level impact of integrating mental health screening and treatment into the primary healthcare system in Sehore district, Madhya Pradesh. India. BMJ Global Health, 4(3), e001344. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001344

Siegfried, N., Parry, C. D. H., Morojele, N. K., & Wason, D. (2001). Profile of drinking behaviour and comparison of self-report with the CAGE questionnaire and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin in a rural Lesotho community. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 36(3), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/36.3.243

Sorsdahl, K., Stein, D. J., Corrigall, J., Cuijpers, P., Smits, N., Naledi, T., & Myers, B. (2015). The efficacy of a blended motivational interviewing and problem solving therapy intervention to reduce substance use among patients presenting for emergency services in South Africa: A randomized controlled trial. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 10, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-015-0042-1

Spottswood, M., Davydow, D. S., & Huang, H. (2017). The Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 25(4), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000136

Sustainable Development Goal 3. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2023). https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3#:~:text=Ensure%20healthy%20lives%20and%20promote%20well%2Dbeing%20for%20all%20at%20all%20ages

Sweetland, A. C., Belkin, G. S., & Verdeli, H. (2014). Measuring Depression and Anxiety in Sub-Saharan Africa. Depression and Anxiety, 31(3), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22142

UNAIDS Lesotho. (2023). UNAIDS Lesotho. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/lesotho

United Nations Development program. (2019). Lesotho District Profile. https://www.undp.org/lesotho/publications/lesotho-district-profile

USAID. (2014). Making the Demographic and Health surveys wealth index comparable. https://www.dhsprogram.com/topics/wealth-index/wealth-index-construction.cfm

van den Broek, M., Gandhi, Y., Sureshkumar, D. S., Prina, M., Bhatia, U., Patel, V., Singla, D. R., Velleman, R., Weiss, H. A., Garg, A., Sequeira, M., Pusdekar, V., Jordans, M. J. D., & Nadkarni, A. (2023). Interventions to increase help-seeking for mental health care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(9), e0002302. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0002302

van der Westhuizen, C., Wyatt, G., Williams, J. K., Stein, D. J., & Sorsdahl, K. (2016). Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test in a low- and middle-income country cross-sectional emergency centre study. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35(6), 702–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12424

Verhey, R., Chibanda, D., Gibson, L., Brakarsh, J., & Seedat, S. (2018). Validation of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist – 5 (PCL-5) in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1688-9

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the involved staff at the Ministry of Health in Lesotho, the SolidarMed Lesotho team, the entire ComBaCaL survey team, and all study participants.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Basel This study is funded by the TRANSFORM grant of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation under the ComBaCaL project (Project no. 7F-10345.01.01; Co-Principal Investigators: AA and NDL). NDL receives his salary from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Eccellenza PCEFP3_181355), AA receives his salary from the Research Fund of the University of Basel, and EF receives his salary from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement (No 801076), through the SSPH + Global PhD Fellowship Programme in Public Health Sciences (GlobalP3HS) of the Swiss School. JMB and GHY are funded by SNSF Ambizione grant (grant # PZ00P1_201690, PI: Belus). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LGF, EF, AA, TIL, NDL and JMB conceptualized the study and design. MPS, MK, MM, and MB collected the data in the field under the supervision of RG and with support from LGF and EF. LGF, TL, and FC performed data analysis. LGF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors commented and provided substantive edits to the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics

All procedures were carried out in line with the ethical standards laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants received information on the clinical procedures in Sesotho and gave written informed consent. Participants who were illiterate gave consent by thumbprint and a witness signature. Once the informed consent process was completed, a signed copy of the form was retained by study staff and a copy was given to participants. This study was reviewed by the Ethics Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland (ID AO_2021-00056) and approved by the National Health Research Ethics Committee in Lesotho (ID139-2021).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Patient and Public Involvement

This study is part of the Community-based chronic care project Lesotho (ComBaCaL). It was designed together with the ComBaCaL steering committee that includes a community representative, as well as representatives from the Ministry of Health of Lesotho. The study was discussed with local authorities (village chiefs, local Ministry of Health), who were engaged throughout the study process.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

*Alain Amstutz and Jennifer M. Belus are shared last authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández, L.G., Yoon, G.H., Firima, E. et al. Prevalence of Mental Health and Substance use Problems and Awareness of Need for Services in Lesotho: Results from a Population-Based Survey. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01309-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01309-w