Abstract

Loneliness is an established risk factor for impaired health. However, the evidence of whether increased alcohol consumption is a coping mechanism to alleviate loneliness for both genders remains sparse. The cross-sectional study included 8898 men and 8910 women (mean age of 56.2 ± 11.5 years) from three population-based cohort studies in Germany (KORA-FF4, GHS, and SHIP. Daily alcohol consumption (g/day) was measured, and risky drinking was identified using gender-specific thresholds (40 g/day for men and 20 g/day for women). Loneliness was assessed by asking if the participants feel lonely. Multivariable regression analyses were employed to examine the association between alcohol use outcomes and loneliness with adjustments for confounders. Women reported feeling lonely more frequently than men (14.8% vs 10.4%). In men, loneliness was positively associated with levels of alcohol consumption (ß = 1.75, SE = 0.76, p = 0.04) and risky drinking (OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.07–1.66, p = 0.02) and was even more profound in men with lower educational levels. In women, loneliness was associated with reduced odds of risky consumption (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.60–0.96, p = 0.02) but not with alcohol consumption levels. The findings indicate gender-differential associations of loneliness with increased levels and risky alcohol consumption in men but with decreased risky consumption in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although painful, negatively perceived social isolation (loneliness) may activate neuroendocrine and behavioural responses that promote short-term self-preservation and motivate individuals to reinforce their existing social relationships or establish new ones. However, loneliness can also carry long-term costs, especially when the perception of social isolation becomes chronic (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010).

The prevalence of chronic loneliness continues to increase in modern life, affecting up to 10% and 20% of the middle-aged and older adult populations, respectively (Surkalim et al., 2022). Previous studies suggested women may be more likely to be lonely than men, particularly among the older population (Luanaigh & Lawlor, 2008; Victor et al., 2006), possibly due to the fact that women are more disadvantaged in terms of health, material resources (Arber & Ginn, 1993), and widowhood (Pinquart and Sörensen, 2001a, b). Furthermore, it is now evident that loneliness has a detrimental effect on health that is comparable with well-established risk factors such as physical activity and obesity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Loneliness itself has been linked with an increased risk of premature death by up to 38% (Elovainio et al., 2017) through impaired cardio-metabolic health (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2003), elevated blood pressure and cortisol, heightened inflammatory responses to stress (Steptoe et al., 2004), and modifications in transcriptional pathways linked with glucocorticoid and inflammatory processes (Cole et al., 2007). Moreover, epidemiological studies have confirmed that loneliness can increase morbidity (Valtorta et al., 2016) with strong gender-dependent differences (Thurston & Kubzansky, 2009), whereby both loneliness and social isolation even increase the risks of coronary heart disease by up to 27% in women (Golaszewski et al., 2022). Further amplifying the negative effects of loneliness on health, individuals who feel lonely have been shown to have increased somatic and psychosocial risk factors and engage in fewer health-promoting behaviours as well as more health-compromising behaviours (Seeman, 2000), making loneliness an urgent public health issue to tackle.

Among coping mechanisms to alleviate loneliness, increased alcohol consumption has traditionally been recognized as a commonly adopted behaviour (Cooper et al., 1995). As thus, alcohol has a long-standing social and cultural context, which may also cultivate an environment of “friendship and togetherness” and is often viewed as a social facilitator (Akerlind & Hörnquist, 1992). However, it is worth noting that the view on experiences and attitudes toward alcohol use has evolved through time. Now, it is also acknowledged that individuals with heavy alcohol consumption are also more likely to become lonely over time as a result of their addiction. Consequently, the extent to which perceived social isolation (i.e. loneliness) may influence alcohol consumption is still unclear. In line with this, previous studies among the general population demonstrated mixed findings.

Conflicting evidence exists on whether loneliness is associated with more frequent at-risk drinking (Akerlind & Hörnquist, 1992) or with reduced alcohol use frequency (Canham et al., 2016) and lower mean alcohol consumption levels (g/day) (Beutel et al., 2017). Although the harmful mental health-related effects of alcohol consumption are known to be different for men and women (Erol & Karpyak, 2015), gender-specific research on the relationship between loneliness and alcohol use in adulthood remains scarce. Therefore, we aimed to analyse this relationship by employing data from three previous population-based studies in middle-aged men and women covering major parts of Germany. We also examined whether various concurrent psychosocial, lifestyle, and clinical risk factors, including sociodemographic factors in the first line (Algren et al., 2020), may modify the gender-specific association between loneliness and alcohol consumption. This study is part of a multi-cohort consortium (GEnder-Sensitive Analyses of mental health; GESA) project (Burghardt et al., 2020) dedicated to distinguishing the prevalence and risks factors of adverse psychosocial outcomes between men and women within the DataSHIELD (Data Aggregation through Anonymous Summary-statistics from Harmonised Individual LevEL Databases) platform (Jones et al., 2012), which allows for joint analyses of three large-scale population-based studies while preserving a high level of data protection.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

Data were derived from the GESA consortium included three major, ongoing, longitudinal cohorts in the middle (Gutenberg Health Study (GHS)), southern (Cooperative Health Research in the Augsburg Region (KORA)), and northeast (Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP)) Germany which have been described in detail elsewhere (Burghardt et al., 2020). Based on the assessments of specific psychosocial variables, the included cohorts were the GHS (2007–2012) (N = 15,010), KORA FF4 (2013–2014) (N = 2279), and the SHIP3 (2008–2012) (N = 1905). After exclusion for participants with missing data in loneliness (N = 856), alcohol consumption (N = 235) and other covariates, the present dataset consists of 8898 men (50%) and 8910 (50%) women with a mean age of 55.4 (± 11.2) for men and 54.8 (± 11.1) for women. Missing data for the loneliness variable was mainly from the KORA (53.5%, n = 458) and GHS (40.8%, n = 349) studies. The missing alcohol variable (n = 235) was from the GHS study. A drop-out analysis of the excluded participants revealed no significant age and gender differences (data not shown). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, including written informed consent of all study participants. This study was approved by the local ethics committees.

Data Harmonization and Handling

We used DataSHIELD to conduct a pooled analysis of multiple cohort study data which enables describing and analysing large-scale and complex interactions in epidemiological studies. Usually, sharing the individual-level data necessary for many epidemiological analyses raises concerns about privacy, particularly in sensitive topics (e.g. drinking habits, social status, and diseases). In DataSHIELD, only non-disclosive summary statistics are shared across sites, and specific individual data remains on local servers and thus inaccessible for all users (Jones et al., 2012). Methods with the potential to distinguish individual data (e.g. scatter plots, outliers, or extreme values identification) are prohibited in DataSHIELD, resulting in more limited statistical functionality than the standard case. However, there are no restrictions on the joint analyses of pooled samples, particularly on the descriptive statistics, and linear and logistic regression analyses that have been planned in the current study.

Dependent Variable (Outcome): Alcohol Consumption

In the standardized interview, information on alcohol intake was based on self-reported amount of standard sized alcoholic drinks (beer, wine, and spirits) each subject had consumed on the previous workday and over the previous weekend, by the following questions: “How much beer/wine/spirits did you drink over the previous weekend (Saturday and Sunday)?” and “How much beer/wine/spirits did you drink on the previous workday (or on the previous Thursday, if Friday was the previous workday)?”. Total intake was calculated by multiplying weekday consumption by five and adding this to weekend consumption, applying the following conversions: 1-L beer = 40 g alcohol, 1-L wine = 100 g alcohol, and 1 shot distilled spirits (0.02 L) = 6.2 g alcohol. Finally, the average number of grams of alcohol consumed per day (g/day) was derived. This 7-day recall method was validated against a 7-day diet record method in a subsample and revealed sufficient validity (Keil et al., 1997). For the present analysis, alcohol consumption was classified into three categories: “no alcohol” (0 g/day), “moderate consumption” (0.1–39.9 g/day for men and 0.1–19.9 g/day for women), and “risky consumption” (≥ 40 g/day for men and ≥ 20 g/day for women) following previous studies regarding cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (Keil et al., 1997; Ruf et al., 2014) and guideline (EMA, 2010). We have combined the moderate consumption group with the no-consumption group to form a dichotomised risky-drinking category. The alcohol consumption categories will enable us to present the characteristics of non-drinkers and moderate drinkers as opposed to those who consumed alcohol more than the established guideline (risky drinking).

Main Covariates: Loneliness

In KORA and GHS, loneliness was assessed with a single question on a five-point Likert scale, “I am frequently alone /have few contacts” rated as 0 = “no, does not apply”, 1 = “yes it applies, but I do not suffer from it”, 2 = “yes, it applies, and I am a little affected”, 3 = “yes, it applies, and I am more likely to be affected”, 4 = “yes, it applies, and I am severely affected”. The item was dichotomized, with “a little affected”, “more likely to be affected”, and “severely affected” responses classified as lonely and the remaining categories as not lonely. A similar single-item measure is commonly used in the literature (Courtin & Knapp, 2017) and has demonstrated a comparable validity to the UCLA Loneliness scale (Reinwarth et al., 2023). In SHIP, loneliness was measured by using three items related to perceived support from the social environment from the Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU), which include, “there is someone very close to me whose help I can always count on”, “there are people who share both joy and sorrow with me”, and “there is someone close to me in whose presence I feel comfortable without any reservations”. Respondents were able to answer on a five-point scale which included categories of “does not apply at all” (1), “does rather not apply” (2), “partially applies” (3), “applies” (4), and “applies exactly” (5). Items were summed up to a total score by adding up these three items. The F-SozU was shown to have a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94) (Fydrich et al., 2009). Previous research demonstrated that the mean score of items on the social support subscale in healthy individuals was 12 (SD ± 2.5) (Hajek et al., 2016). We have chosen the 20th percentile of the total score (< 12) as cut-off and dichotomized those with a total score ≤ 12 as “lonely”, whereas those with > 12 as less “lonely”. The dichotomization of loneliness status is particularly important in understanding the participants’ characteristics as well as allowing the assessment of potential covariates by showing the distribution of relevant variables (e.g. sociodemographic, lifestyle, clinical, and psychological factors) within each group (lonely vs. less lonely). This enables us to determine whether there are any imbalances or differences between the exposure groups that should be considered during the next regression analysis.

Other Covariates

Sociodemographic factors were assessed, including age, gender, years of education, marital status, living arrangement (living alone vs living with someone), and employment status. Lifestyle and clinical factors include smoking, physical activity, body mass index, and self-reported type 2 diabetes. Participants were classified as smokers when they reported that they currently smoke at least one cigarette per day. Participants were classified as “physically inactive” during leisure time if they did not regularly participate in sports and were not active for at least 1 h per week in summer and winter. Body height and body weight were determined by trained medical staff following a standardized protocol. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilogrammes divided by high in square metres. Type 2 diabetes was self-reported by the participants in and validated by the physicians. Psychological factors include sleeping problems, depressive symptoms, and anxiety. Sleeping problems were assessed based on the difficulty of initiating and maintaining sleep. Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and dichotomized by using a total score cut-off ≥ 9 for severe depressive symptoms and < 9 for mild or no depressive symptom) (Kroenke et al., 2001). Anxiety was assessed by dichotomization based on the cut-off ≥ 3 of the total score using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-2 instrument (Kroenke et al., 2007).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses of the pooled sample or cohort-specific populations were performed separately for men and women. Descriptive data of sociodemographic, lifestyle, clinical, and psychological characteristics were stratified by alcohol consumption categories and loneliness status. Participant’s characteristics are presented as proportions or as means (± standard deviation, SD), accordingly. Bivariate associations between groups were tested using the χ2 test for categorical variables and generalized linear regression (GLM) models for continuous variables.

Multiple generalized linear regression (GLM) models were performed to consider the interaction effect of gender and loneliness on alcohol consumption (in continuous values, g/day) by including the loneliness by gender (loneliness*gender) interaction term in the models. In the pooled study population, gender-stratified multiple generalized linear regression models were employed to calculate ß estimates, standard errors (SE), and p values for the associations between feeling lonely (vs not lonely) and alcohol consumption levels (in continuous values, g/day) with different steps of adjustments. Model 1 was adjusted for age and a study cohort variable to account for the cohort effect. Model 2 was further adjusted for education level and employment status. Further adjustments were performed on a reduced subset of participants due to missing data in physical activity, depression, anxiety, and sleep problems (n = 15896). Model 3 was additionally adjusted for BMI, smoking status, and physical activity. Model 4 was further adjusted for sleep problems, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Deviance residuals were examined in order to evaluate the model’s goodness-of-fit. The increase in deviance is evidence of a significant lack of fit. The residual deviance statistics revealed that the final model was the preferred model fit indicated by the values (data not shown).

Additional regression models were fitted to assess if other covariates modify the association between loneliness and alcohol consumption. Multiplicative interaction analyses were employed by introducing the interaction terms of loneliness by other available covariates on the association with alcohol consumption in fully-adjusted models. In the case of significant interaction, the regression analyses were further stratified by the relevant variable.

Sensitivity Analyses

The analyses were repeated by conducting multivariable logistic regression models to examine the association between loneliness and alcohol consumption categories. In these models, we used binomial logistic regression models from the GLM function to examine the association between loneliness and dichotomized categories of “risky” versus “moderate and no” alcohol consumption.

All statistical analyses were performed in DataSHIELD 4.1 with the R-Version of 3.5.2, and p values below 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Study Sample

The present investigation includes 8898 men (50%) and 8910 (50%) women, with a mean age of 56.2 (± 11.5) years (men: 55.4 ± 11.2; women: 54.8 ± 11.1) and alcohol consumption levels of 11.1 (± 15.3) g/day. Participants’ characteristics of sociodemographic, lifestyle, clinical and psychological factors stratified by gender are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Descriptive Analyses: Alcohol Consumption

The gender-specific mean alcohol consumption level was 15.9 g/day (± 20.0) in men and 6.5 g/day (± 10.6) in women. Correspondingly, 1016 men (11.4%) and 913 women (10.3%) met the criteria for risky alcohol consumption (≥ 40 g/day for men and ≥ 20 g/day for women). As presented in Table 1, men and women with risky alcohol consumption are more likely to have lower educational levels, poor lifestyle behaviours, and suffer from depressive symptoms. With respect to gender differences in risky alcohol use, men were more likely to experience loneliness, whereas women experienced more anxiety symptoms. Additionally, among those living alone, women were more likely to report no alcohol consumption (no consumption: 18.8%; moderate: 14.8%; at-risk: 15.3%), whereas slightly more men living alone reported alcohol consumption levels exceeding the recommended guideline (≥ 40 mg/day) (no consumption: 14%; moderate: 11.2%; at-risk: 15.6%).

Descriptive Analyses: Loneliness

Loneliness was more prevalent in women (14.8%, n = 1316) than men (10.4%, n = 929). As presented in Table 2, men and women who experience loneliness are more likely to be less educated, living alone, unmarried, smoked regularly, less active, and have more mental health impairments. Differences between gender were marginal; loneliness was associated with have higher BMI and diabetes in women, whereas loneliness was associated with younger age and higher alcohol consumption levels in men.

Association Between Loneliness and Alcohol Consumption

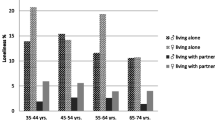

Figure 1 illustrates the bivariate association between loneliness and alcohol consumption levels. Lonely men presented a significantly higher mean alcohol consumption level (g/day) than not lonely men (16.9 ± 23.2 vs. 15.6 ± 19.4; p = 0.049). In contrast, women who reported feeling lonely had lower alcohol consumption levels than their not lonely counterparts, with a non-statistically significant difference (6.1 ± 10.9 vs. 6.5 ± 10.6; p = 0.18). Similarly, more men (13.8%) have both loneliness and risky drinking patterns than women (8.7%).

Additionally, multivariable linear regression models were fitted to control for potential confounding factors and assess the independent association of loneliness on alcohol consumption levels (Supplementary Table 2). Driven by a significant interaction between loneliness by gender on alcohol consumption levels (fully-adjusted p for interaction term = 0.02), gender-stratified analyses were performed (Table 3).

Corresponding to the bivariate analysis, the GLM models revealed that loneliness was linearly associated with higher levels of alcohol consumption (g/day) in men, which was substantiated following adjustment for concurrent risk factors (model 4: ß = 1.75, SE = 0.76, p = 0.04). However, in women, loneliness was negatively associated with alcohol consumption levels but the association did not reach statistical discernable effect (model 4: ß = − 0.45, SE = 0.34, p = 0.51).

Beyond the effect of loneliness on alcohol consumption, the regression analyses demonstrated that older age, higher education levels, smoking, lower BMI, and no T2DM were significantly associated with higher alcohol consumption levels in both men and women. While sleeping problems was positively associated with alcohol use in men, full-time employment, physical activity, and anxiety were significantly associated with increased alcohol use in women.

We performed multiplicative interaction analyses with other covariates in the study to further understand the link between loneliness and alcohol consumption, with most interactions tested yielding non-statistically significant findings (p > 0.05). A statistically significant interaction was only seen with educational levels in men (p interaction = 0.007), indicating a potential effect modification by education levels in men. A stratified analysis according to high (≥ 12 years) or low (< 12 years) educational levels revealed that the association between loneliness and increased alcohol consumption levels (g/day) was amplified in men with low education, which then reached borderline statistical significance in the fully-adjusted model (crude model: ß = 2.28, SE = 1.08, p = 0.04; full model: ß = 2.09, SE = 1.20, p = 0.08; Supplementary Table 3).

Sensitivity Analyses

We also examined the gender-specific association between loneliness and alcohol consumption categorically (“risky” versus “moderate and no” consumption) and confirmed the previously reported findings with the continuous alcohol consumption variable (Supplementary Table 4). Multivariable-adjusted logistic regression analyses in men revealed that participants reported feeling lonely was associated with increased odds of having risky alcohol consumption in comparison to their not lonely counterparts (model 1: OR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.07–1.60, p = 0.01; model 2: 1.33 (1.07–1.66, p = 0.02). However, in women, being lonely was significantly associated with decreased odds of having risky consumption compared with those who are not lonely (model 1: OR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.66 – 0.99, p = 0.04; model 2: OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.60–0.96, p = 0.02). In other words, loneliness was associated with risky drinking in men but with moderate/no consumption in women.

Discussion

The present investigation examined the gender-specific association between loneliness and alcohol consumption in 8898 men and 8910 women (mean age 55 ± 11 years) from the multi-cohort GESA consortium. We found that men had significantly higher mean levels of alcohol consumption (11.1 ± 15.3 g/day) compared to women (6.5 ± 10.6 g/day) and that the prevalence of risky alcohol consumption was also higher in men (11.4%) compared to women (10.3%). As a major new finding, the investigation evidenced that men who experience loneliness exhibited a higher mean alcohol consumption and a higher percentage of risky alcohol consumption patterns compared to women who feel lonely (men: 13.8%; women: 8.7%).

Of note, gender differences in the association between loneliness and alcohol consumption were independent of sociodemographic, lifestyle, metabolic, and psychological factors indicating that these gender-differential associations are robust which delineate the lack of gender analyses as serious shortcoming of the previously contradictory results on this particular loneliness—alcohol consumption association (Algren et al., 2020; Beutel et al., 2017; Canham et al., 2016). Indeed, earlier findings on the association between loneliness and drinking patterns seem to serve as all clear signals: Two large population-based studies in Germany also demonstrated that high levels of alcohol consumption (Beutel et al., 2017) and more frequent (i.e. occasional and daily) drinking (Hajek et al., 2017) were associated with decreased loneliness in adulthood. Meanwhile, the population-based HRS (N = 2004, mean age 65 years) showed that loneliness was associated with a reduced average weekly frequency of alcohol use, but the study included older US samples and reported a higher prevalence of loneliness (15.7%) than the current population (Canham et al., 2016). Previous studies, however, did not provide gender-specific estimates. Based on the recommended drinking limit threshold for women, our gender-specific analyses revealed an association between loneliness and non-risky drinking (no or moderate consumption) compared with risky drinking. In the present study, we observed that women who do not drink were more likely to live alone, be physically inactive, had high BMI, and type 2 diabetes, reflecting a poorer risk factors’ profile. This similar trend was also seen in the German Ageing Study, whereby a large proportion of non-drinkers were speculated to be ex-drinkers due to the high prevalence rates of chronic health conditions (Hajek et al., 2017), supporting the “sick quitter effect” idea that these individuals are abstinent from alcohol for health reasons (Shaper, 1990). Due to the lack of available alcohol abstinent data, it is not possible to definitively ascertain whether the women identified as “non-drinkers” are indeed former drinkers. However, other studies failed to show a significant association between loneliness and alcohol use (Algren et al., 2020; Kobayashi & Steptoe, 2018; Richard et al., 2017; Wootton et al., 2021), which could be attributed to the differences in “at-risk” drinking definition. Future research should consider both the frequency (Bragard et al., 2022) and the quantity of alcohol consumption per occasion, given that conflicting evidence indicates that the former is generally positively correlated with health outcomes, while the latter is negatively correlated (Marees et al., 2020).

The present investigation disclosed that the link between loneliness and high alcohol consumption was more profound in men with lower educational levels—a finding which has been shown before for an increased likelihood of risky drinking in men (French et al., 2014). Consequently, individuals with educational or socioeconomic disadvantages may face barriers to healthcare facilities and stigma, restricting their access to services that could assist them with alcohol use-related issues (Hutt & Gilmour, 2010; Schomerus et al., 2011). However, there is also conflicting evidence that high SES or better educational levels are associated with a higher vulnerability to drink heavily in women than men (Kuntsche et al., 2006; Lange et al., 2016; Stelander et al., 2022). Although we could not confirm the association between loneliness and increased alcohol use in higher educational level among women, our regression analysis also showed that full-time employment is associated with high alcohol consumption in women compared to unemployment. The results may suggest the “contagion effect” of significant others whereby women in higher job positions more often behave similarly to men in the workplace or simply have more occasions to drink, e.g. in business meetings (Haavio-Mannila, 1991; Hammer & Vaglum, 1989; Parker & Harford, 1992). However, being in a “traditional role” (unemployed, partner, and parent) has been commonly associated with the lowest risk of heavy drinking in women (Kuntsche et al., 2006).

There are several potential reasons why women tend to exhibit lower alcohol consumption than men when experiencing loneliness. Recent evidence suggests differences in the neural mechanisms underlying the experience of chronic stress (i.e. loneliness) and alcohol reward processing between men and women (Peltier et al., 2019), with men exhibiting stronger activation in the striatum in response to alcohol cues compared to women (Kaag et al., 2019). Another important factor is based on societal gender roles and expectations, which may reflect the loneliness associated with lower alcohol consumption in women. Drinking alcohol may be more socially acceptable for men (Dempster, 2011), while women may face greater stigma or disapproval for consuming alcohol (Neve et al., 1997). Furthermore, a lack of social companionship may reduce the opportunity for social drinking (Dare et al., 2014), suggesting that socially isolated women may have fewer drinking opportunities, as social networks continue to be an important influence on alcohol use (Akers et al., 1989; Platt et al., 2010). Nevertheless, women may be more likely to seek social support, engage in emotional expression (Meléndez et al., 2012), or turn to alternative coping strategies not associated with drinking such as exercise, hobbies, or seeking professional help (Graves et al., 2021; Oliver et al., 2005; Weaver et al., 2000), which of these aspects must be considered in future studies. Another possible explanation is that experiences such as marital dissolution, divorce, or separation have been associated with loneliness (von Soest et al., 2020), which may influence drinking behaviour. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that women who have experienced marital dissolution decreased their use of alcohol, and this change was found to be integrally connected to subsequent social and structural supports made available to them (Poole et al., 2008; Wilsnack et al., 1991).

Our data also demonstrated gender differences in loneliness, with a higher prevalence among women (14%) than men (10%), as supported by previous research that reported gender differences in higher levels of loneliness from Europe (Hansen & Slagsvold, 2016; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, 2014; ONS, 2018) and a sample of 28 countries (Schermer et al., 2023). Evidence of gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan may become apparent with advancing age due to their longer life expectancy (Pinquart and Sörensen, 2001a, b; Schermer et al., 2023), which is associated with widowhood, living alone, chronic illness, disability, and functional limitations. Despite being disadvantaged by their circumstances, the impact of loneliness on adverse mental and physical health was less profound in women than in men. Previous research indicated that men are more likely to experience loneliness with stronger associations with adverse mental health conditions than women (Zebhauser et al., 2014), indicating that women seem to have better capabilities than men to overcome loneliness (Schmitt & Kurdek, 1985). Men may have a lower social acceptance of loneliness, potentially due to stigmatization, than women, particularly during young adulthood (Borys & Perlman, 1985), although this has been contested. However, contradictory findings exist whereby a recent large study across 237 countries showed that younger males were associated with higher levels of loneliness than their female counterparts (Barreto et al., 2021) and a meta-analysis with half of the studies from the USA did not find gender differences in loneliness (Maes et al., 2019). Interestingly, recent in-depth analysis of over 28 countries examined the cross-country differences in prevalence of loneliness which was primarily due to individualism and collectivism cultural constructs. Individuals from countries whose culture reflects individuality and a hierarchical society tend to report more feelings of loneliness than those from cultures of egalitarianism (Schermer et al., 2023). However, the majority of study participants were young adults, limiting the study’s ability to capture age-related variation accurately. Given the limited and contradicting findings, future research should examine cross-country gender differences in loneliness with a contextual, cultural focus.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of the study is the large sample size of equally represented men and women from three different population-based cohort studies in Germany that have a high response rate and a standardized quality assessment. The dataset also allows for a robust adjustment for a variety of covariates. Our investigation into the gender-specific association between loneliness and alcohol consumption yields important findings but has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not imply causality. However, loneliness has been shown to precede the first drink on a typical drinking day among older adults who were alcohol abusers (Schonfeld & Dupree, 1991). Second, the present study utilized a self-reported alcohol consumption questions which is particularly susceptible to underreporting (Pernanen, 1974) as well as the tendency of participants to provide socially desirable responses. Individuals may consume more alcohol on certain weekdays than others; thus, assuming that alcohol consumption on the previous workday is representative of consumption across all five workdays could result in measurement error. The present study also does not have data on alcohol use disorders and abstainers. Nevertheless, a previous study among KORA cohort participants reported that the proportion of individuals with elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transferase, a marker of alcohol use, did not indicate a misclassification of drinkers in the abstinent group (Ruf et al., 2014). It should be noted that excessive alcohol consumption or heavy alcohol use does not always imply addiction or an alcohol use disorder. However, although we did not assess alcohol use disorders in this study, a substantial body of literature confirms that drinking above the guideline levels is predictive of the onset of alcohol disorders (Hasin et al., 1999), adverse health (Dawson et al., 2005), mental health and cognitive impairments (Dawson et al., 1996; Hindmarch et al., 1991), and social consequences (Midanik et al., 1996; Russell et al., 2004).

Furthermore, loneliness is a complex and multi-dimensional construct. Thus, we acknowledge the limitation of employing a single-item loneliness measure and perceived levels of social support as a proxy for loneliness. Loneliness has been associated with lower perceived social support which assesses the quality or adequacy of social support from a subjective perspective (Coyle & Dugan, 2012; Groarke et al., 2020; Routasalo et al., 2006). For instance, comparable to the F-SozU, other widely used perceived social support measures, the Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988) and the Subjective Support Subscale of Duke Social Support Index (DSSI) (Koenig et al., 1993), consist of items such as “I have friends with whom I can share joys and sorrows”, which have a high degree of overlap with loneliness measures. Similarly, numerous studies have found negative relationships between loneliness and perceived social support (Chrostek et al., 2016; Lasgaard et al., 2010; Pamukçu & Meydan, 2010; Salimi & Bozorgpour, 2012). These concepts resemble loneliness as subjective evaluations of the quality and impact of social support and relationships. Due to this conceptual overlap, the present study includes the social support from F-SozU as a proxy for the loneliness measure. Finally, reverse causality is possible in our findings, whereby heavy alcohol consumption can also result in social withdrawal. For some individuals, moderate alcohol consumption increases the desire to engage in prosocial behaviours and renders these social interactions more enjoyable; likewise, social settings can increase total alcohol intake as well as the positive subjective effects of alcohol (de Wit & Sayette, 2018; Van Hedger et al., 2017).

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the sparse literature examining gender differences in how loneliness may affect alcohol use. Loneliness can be threatening when one is unable to resolve loneliness leading to a prolonged unpleasant state (e.g. depression and maladaptive behaviours that may be used to escape the feeling) (Cacioppo et al., 2006). While loneliness and depression can be interconnected, loneliness focuses on social connections, while depression involves a range of symptoms (e.g. persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest) which may affect overall functioning. Depressive symptoms, in turn, may further enhance alcohol-related problems, particularly among women (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2013). Therefore, it is important to consider the potential confounding role of depression on the relationship between loneliness and alcohol consumption, as conducted in the present study. Future research should also focus on the mechanisms driving loneliness leading to alcohol consumption that can be translated into effective intervention strategies. For instance, a recent study has explored the personality trait of authenticity (i.e. the ability to process self-relevant information without bias) that can help individuals to accept loneliness without experiencing excessive discomfort, thus protecting them from alcohol-related problems associated with loneliness (Bryan et al., 2017). In another study, self-esteem was found to partially mediate the loneliness associated with alcohol abuse, suggesting that self-esteem may play a major role in the development of alcohol misuse, particularly in lonely individuals (Lau et al., 2023). Moreover, changing one’s attitude about drinking before targeting behavioural modification in alcohol misuse is also a promising avenue for a potential intervention strategy (DiBello et al., 2022).

Conclusion

This study suggests gender-differential findings that loneliness is related to increased alcohol consumption in men, particularly in those with lower educational levels, whereas loneliness is associated with reduced risky consumption in women. We speculate from these results that gender expectations in relation to loneliness and alcohol use could be related to a greater social acceptance of drinking in men than women (Landrine et al., 1988). Future work in the gender-related psychosocial aspects of alcohol use should focus on conducting longitudinal studies to understand the dynamic relationship between gender, loneliness, and alcohol use over time. Furthermore, investigating contextual factors and evaluating existing policies from a gender-responsive perspective can inform the development of evidence-based interventions and policies that effectively address harmful alcohol use in both men and women. To this end, healthcare providers should remain vigilant of the influence of loneliness on an individual’s drinking behaviours, and discuss methods by which patients can reduce and prevent loneliness, especially among socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals.

Data Availability

GESA is a multi-cohort project building on GHS, SHIP, and KORA, where the data availability is limited to the local storage guidelines. Data access rights must be requested at each cohort.

References

Akerlind, I., & Hörnquist, J. O. (1992). Loneliness and alcohol abuse: A review of evidences of an interplay. Social Science & Medicine, 34(4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(92)90300-f

Akers, R. L., La Greca, A. J., Cochran, J., & Sellers, C. (1989). Social learning theory and alcohol behavior among the elderly. Sociological Quarterly, 30(4), 625–638.

Algren, M. H., Ekholm, O., Nielsen, L., Ersbøll, A. K., Bak, C. K., & Andersen, P. T. (2020). Social isolation, loneliness, socioeconomic status, and health-risk behaviour in deprived neighbourhoods in Denmark: A cross-sectional study. SSM Popul Health, 10, 100546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100546

Arber, S., & Ginn, J. (1993). Gender and inequalities in health in later life. Social Science & Medicine, 36(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90303-L

Barreto, M., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2021). Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, 110066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110066

Beutel, M. E., Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Reiner, I., Jünger, C., Michal, M., Wiltink, J., Wild, P. S., Münzel, T., Lackner, K. J., & Tibubos, A. N. (2017). Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x

Borys, S., & Perlman, D. (1985). Gender Differences in Loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 11(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167285111006

Bragard, E., Giorgi, S., Juneau, P., & Curtis, B. L. (2022). Daily diary study of loneliness, alcohol, and drug use during the COVID-19 PANDEMIC. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 46(8), 1539–1551. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14889

Bryan, J. L., Baker, Z. G., & Tou, R. Y. (2017). Prevent the blue, be true to you: Authenticity buffers the negative impact of loneliness on alcohol-related problems, physical symptoms, and depressive and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(5), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315609090

Burghardt, J., Tibubos, A. N., Otten, D., Brähler, E., Binder, H., Grabe, H., Kruse, J., Ladwig, K. H., Schomerus, G., Wild, P. S., & Beutel, M. E. (2020). A multi-cohort consortium for GEnder-Sensitive Analyses of mental health trajectories and implications for prevention (GESA) in the general population in Germany. BMJ Open, 10(2), e034220. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034220

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M., Berntson, G. G., Nouriani, B., & Spiegel, D. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 1054–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007

Canham, S. L., Mauro, P. M., Kaufmann, C. N., & Sixsmith, A. (2016). Association of Alcohol Use and Loneliness Frequency Among Middle-Aged and Older Adult Drinkers. Journal of Aging and Health, 28(2), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315589579

Chrostek, A., Grygiel, P., Anczewska, M., Wciórka, J., & Świtaj, P. (2016). The intensity and correlates of the feelings of loneliness in people with psychosis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 70, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.07.015

Cole, S. W., Hawkley, L. C., Arevalo, J. M., Sung, C. Y., Rose, R. M., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biology, 8(9), R189. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r189

Cooper, M. L., Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Mudar, P. (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 990–1005. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990

Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12311

Coyle, C. E., & Dugan, E. (2012). Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 24(8), 1346–1363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264312460275

Dare, J., Wilkinson, C., Allsop, S., Waters, S., & McHale, S. (2014). Social engagement, setting and alcohol use among a sample of older Australians. Health and Social Care in the Community, 22(5), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12110

Dawson, D. A., Archer, L. D., & Grant, B. F. (1996). Reducing alcohol-use disorders via decreased consumption: A comparison of population and high-risk strategies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 42(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-8716(96)01260-4

Dawson, D. A., Grant, B. F., & Li, T. K. (2005). Quantifying the risks associated with exceeding recommended drinking limits. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(5), 902–908. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.alc.0000164544.45746.a7

de Wit, H., & Sayette, M. (2018). Considering the context: Social factors in responses to drugs in humans. Psychopharmacology (berl), 235(4), 935–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-4854-3

Dempster, S. (2011). I drink, therefore I’m man: Gender discourses, alcohol and the construction of British undergraduate masculinities. Gender and Education, 23(5), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2010.527824

DiBello, A. M., Hatch, M. R., Miller, M. B., Mastroleo, N. R., & Carey, K. B. (2022). Attitude toward heavy drinking as a key longitudinal predictor of alcohol consumption and problems. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 46(4), 682–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14800

Elovainio, M., Hakulinen, C., Pulkki-Råback, L., Virtanen, M., Josefsson, K., Jokela, M., Vahtera, J., & Kivimäki, M. (2017). Contribution of risk factors to excess mortality in isolated and lonely individuals: An analysis of data from the UK Biobank cohort study. Lancet Public Health, 2(6), e260–e266. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30075-0

EMA, E. M. A. (2010). Guideline on the development of medicinal products for the treatment of alcohol dependence. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-development-medicinal-products-treatment-alcohol-dependence_en.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2023

Erol, A., & Karpyak, V. M. (2015). Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 156, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.023

French, D. J., Sargent-Cox, K. A., Kim, S., & Anstey, K. J. (2014). Gender differences in alcohol consumption among middle-aged and older adults in Australia, the United States and Korea. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 38(4), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12227

Fydrich, T., Sommer, G., Tydecks, S., & Brähler, E. (2009). Fragebogen zur sozialen unterstützung (F-SozU): Normierung der Kurzform (K-14). Zeitschrift Für Medizinische Psychologie, 18(1), 43–48.

Golaszewski, N. M., LaCroix, A. Z., Godino, J. G., Allison, M. A., Manson, J. E., King, J. J., Weitlauf, J. C., Bea, J. W., Garcia, L., Kroenke, C. H., Saquib, N., Cannell, B., Nguyen, S., & Bellettiere, J. (2022). Evaluation of Social isolation, loneliness, and cardiovascular disease among older women in the US. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e2146461–e2146461. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46461

Graves, B. S., Hall, M. E., Dias-Karch, C., Haischer, M. H., & Apter, C. (2021). Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PloS one, 16(8), e0255634. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255634

Groarke, J. M., Berry, E., Graham-Wisener, L., McKenna-Plumley, P. E., McGlinchey, E., & Armour, C. (2020). Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PloS one, 15(9), e0239698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239698

Haavio-Mannila, E. (1991). Impact of co-workers on female alcohol use. Contemp. Drug Probs., 18, 597.

Hajek, A., Bock, J.-O., Weyerer, S., & König, H.-H. (2017). Correlates of alcohol consumption among Germans in the second half of life Results of a population-based observational study. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0592-3

Hajek, A., Brettschneider, C., Lange, C., Posselt, T., Wiese, B., Steinmann, S., Weyerer, S., Werle, J., Pentzek, M., Fuchs, A., Stein, J., Luck, T., Bickel, H., Mösch, E., Wolfsgruber, S., Heser, K., Maier, W., Scherer, M., Riedel-Heller, S. G., & König, H.-H. (2016). Gender differences in the effect of social support on health-related quality of life: Results of a population-based prospective cohort study in old age in Germany. Quality of Life Research, 25(5), 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1166-5

Hammer, T., & Vaglum, P. (1989). The increase in alcohol consumption among women: A phenomenon related to accessibility or stress? A general population study. British Journal of Addiction, 84(7), 767–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03056.x

Hansen, T., & Slagsvold, B. (2016). Late-Life Loneliness in 11 European Countries: Results from the Generations and Gender Survey. Social Indicators Research, 129(1), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1111-6

Hasin, D., Carpenter, K. M., & Paykin, A. (1999). At-risk drinkers in the household and short-term course of alcohol dependence. J Stud Alcohol, 60(6), 769–775. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1999.60.769

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 17(1, Supplement), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Hindmarch, I., Kerr, J. S., & Sherwood, N. (1991). The effects of alcohol and other drugs on psychomotor performance and cognitive function. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 26(1), 71–79.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Hutt, P., & Gilmour, S. (2010). Tackling inequalities in general practice (pp. 1–37). The King’s Fund.

Jones, E. M., Sheehan, N. A., Masca, N., Wallace, S. E., Murtagh, M. J., & Burton, P. R. (2012). DataSHIELD – shared individual-level analysis without sharing the data: a biostatistical perspective. Norsk Epidemiologi, 21(2). https://doi.org/10.5324/nje.v21i2.1499

Kaag, A. M., Wiers, R. W., de Vries, T. J., Pattij, T., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2019). Striatal alcohol cue-reactivity is stronger in male than female problem drinkers. European Journal of Neuroscience, 50(3), 2264–2273. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.13991

Keil, U., Chambless, L. E., Döring, A., Filipiak, B., & Stieber, J. (1997). The relation of alcohol intake to coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality in a beer-drinking population. Epidemiology, 8(2), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199703000-00005

Kobayashi, L. C., & Steptoe, A. (2018). Social isolation, loneliness, and health behaviors at older ages: Longitudinal cohort study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 52(7), 582–593. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kax033

Koenig, H. G., Westlund, R. E., George, L. K., Hughes, D. C., Blazer, D. G., & Hybels, C. (1993). Abbreviating the Duke social support index for use in chronically ill elderly individuals. Psychosomatics, 34(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0033-3182(93)71928-3

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Kuntsche, S., Gmel, G., Knibbe, R. A., Kuendig, H., Bloomfield, K., Kramer, S., & Grittner, U. (2006). Gender and cultural differences in the association between family roles, social stratification, and alcohol use: A European cross-cultural analysis. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 41(1), i37-46. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agl074

Landrine, H., Bardwell, S., & Dean, T. (1988). Gender expectations for alcohol use: A study of the significance of the masculine role. Sex Roles, 19(11), 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288986

Lange, C., Manz, K., Rommel, A., Schienkiewitz, A., & Mensink, G. B. M. (2016). Alcohol consumption of adults in Germany: Harmful drinking quantities, consequences and measures. J Health Monit, 1(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.17886/rki-gbe-2016-029

Lasgaard, M., Nielsen, A., Eriksen, M. E., & Goossens, L. (2010). Loneliness and social support in adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0851-z

Lau, A., Li, R., Huang, C., Du, J., Heinzel, S., Zhao, M., & Liu, S. (2023). Self-esteem mediates the effects of loneliness on problematic alcohol use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01035-9

Luanaigh, C. O., & Lawlor, B. A. (2008). Loneliness and the health of older people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(12), 1213–1221. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2054

Maes, M., Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Van den Noortgate, W., & Goossens, L. (2019). Gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan: A meta–analysis. European Journal of Personality, 33(6), 642–654. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2220

Marees, A. T., Smit, D. J. A., Ong, J. S., MacGregor, S., An, J., Denys, D., Vorspan, F., van den Brink, W., & Derks, E. M. (2020). Potential influence of socioeconomic status on genetic correlations between alcohol consumption measures and mental health. Psychological Medicine, 50(3), 484–498. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291719000357

Meléndez, J. C., Mayordomo, T., Sancho, P., & Tomás, J. M. (2012). Coping strategies: Gender differences and development throughout life span. Span J Psychol, 15(3), 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n3.39399

Midanik, L. T., Tam, T. W., Greenfield, T. K., & Caetano, R. (1996). Risk functions for alcohol-related problems in a 1988 US national sample. Addiction, 91(10), 1427–1437. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911014273.x

Neve, R. J., Lemmens, P. H., & Drop, M. J. (1997). Gender differences in alcohol use and alcohol problems: Mediation by social roles and gender-role attitudes. Substance Use and Misuse, 32(11), 1439–1459. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089709055872

Nicolaisen, M., & Thorsen, K. (2014). Who are Lonely? Loneliness in Different Age Groups (18–81 Years Old), Using two measures of loneliness. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 78(3), 229–257. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.78.3.b

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Desrosiers, A., & Wilsnack, S. C. (2013). Predictors of alcohol-related problems among depressed and non-depressed women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 967–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.022

Oliver, M. I., Pearson, N., Coe, N., & Gunnell, D. (2005). Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186(4), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.4.297

ONS, O. o. N. S. U. (2018). What characteristics and circumstances are associated with feeling lonely? https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/lonelinesswhatcharacteristicsandcircumstancesareassociatedwithfeelinglonely/2018-04-10#profiles-of-loneliness. Accessed 5 Jun 2023

Pamukçu, B., & Meydan, B. (2010). The role of empathic tendency and perceived social support in predicting loneliness levels of college students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 905–909.

Parker, D. A., & Harford, T. C. (1992). Gender-role attitudes, job competition and alcohol consumption among women and men. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 16(2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01359.x

Peltier, M. R., Verplaetse, T. L., Mineur, Y. S., Petrakis, I. L., Cosgrove, K. P., Picciotto, M. R., & McKee, S. A. (2019). Sex differences in stress-related alcohol use. Neurobiol Stress, 10, 100149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100149

Pernanen, K. (1974). Validity of survey data on alcohol use, in “research advances in alcohol and drug problems” Vol. I (RJ Gibbins, Y. Israel, H. Kalant, RE Popham, W. Schmidt, and RG Smart, eds.). In: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2001a). Gender differences in self-concept and psychological well-being in old age: A meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 56(4), P195–P213. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/56.4.P195

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2001b). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis [Article]. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23(4), 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2304_2

Platt, A., Sloan, F. A., & Costanzo, P. (2010). Alcohol-consumption trajectories and associated characteristics among adults older than age 50. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 71(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2010.71.169

Poole, N., Greaves, L., Jategaonkar, N., McCullough, L., & Chabot, C. (2008). Substance use by women using domestic violence shelters. Substance Use & Misuse, 43(8–9), 1129–1150. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080801914360

Reinwarth, A. C., Ernst, M., Krakau, L., Brähler, E., & Beutel, M. E. (2023). Screening for loneliness in representative population samples: Validation of a single-item measure. PloS one, 18(3), e0279701. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279701

Richard, A., Rohrmann, S., Vandeleur, C. L., Schmid, M., Barth, J., & Eichholzer, M. (2017). Loneliness is adversely associated with physical and mental health and lifestyle factors: Results from a Swiss national survey. PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0181442–e0181442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181442

Routasalo, P. E., Savikko, N., Tilvis, R. S., Strandberg, T. E., & Pitkälä, K. H. (2006). Social contacts and their relationship to loneliness among aged people - a population-based study. Gerontology, 52(3), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1159/000091828

Ruf, E., Baumert, J., Meisinger, C., Döring, A., Ladwig, K.-H., investigators, M. K. (2014). Are psychosocial stressors associated with the relationship of alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality? BMC Public Health, 14, 312–312. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-312

Russell, M., Light, J. M., & Gruenewald, P. J. (2004). Alcohol consumption and problems: The relevance of drinking patterns. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(6), 921–930. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.alc.0000128238.62063.5a

Salimi, A., & Bozorgpour, F. (2012). Percieved social support and social-emotional loneliness. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 2009–2013.

Schermer, J. A., Branković, M., Čekrlija, Đ., MacDonald, K. B., Park, J., Papazova, E., Volkodav, T., Iliško, D., Wlodarczyk, A., Kwiatkowska, M. M., Rogoza, R., Oviedo-Trespalacios, O., Ha, T. T. K., Kowalski, C. M., Malik, S., Lins, S., Navarro-Carrillo, G., Aquino, S. D., Doroszuk, M., . . . Kruger, G. (2023). Loneliness and vertical and horizontal collectivism and individualism: A multinational study. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 4, 100105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2023.100105

Schmitt, J. P., & Kurdek, L. A. (1985). Age and gender differences in and personality correlates of loneliness in different relationships. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(5), 485–496. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4905_5

Schomerus, G., Lucht, M., Holzinger, A., Matschinger, H., Carta, M. G., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2011). The stigma of alcohol dependence compared with other mental disorders: A review of population studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 46(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agq089

Schonfeld, L., & Dupree, L. W. (1991). Antecedents of drinking for early- and late-onset elderly alcohol abusers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 52(6), 587–592. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1991.52.587

Seeman, T. E. (2000). Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults [Review]. American Journal of Health Promotion, 14(6), 362–370. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.362

Shaper, A. G. (1990). Alcohol and mortality: a review of prospective studies. Br J Addict, 85(7), 837–847; discussion 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb03710.x

Stelander, L. T., Høye, A., Bramness, J. G., Wynn, R., & Grønli, O. K. (2022). Sex differences in at-risk drinking and associated factors-a cross-sectional study of 8,616 community-dwelling adults 60 years and older: The Tromsø study, 2015–16. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02842-w

Steptoe, A., Owen, N., Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., & Brydon, L. (2004). Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00086-6

Surkalim, D. L., Luo, M., Eres, R., Gebel, K., van Buskirk, J., Bauman, A., & Ding, D. (2022). The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 376, e067068. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-067068

Thurston, R. C., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2009). Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(8), 836–842. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b40efc

Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790

Van Hedger, K., Bershad, A. K., & de Wit, H. (2017). Pharmacological challenge studies with acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 85, 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.08.020

Victor, C. R., Scambler, S. J., Marston, L., Bond, J., & Bowling, A. (2006). Older people’s experiences of loneliness in the UK: Does gender matter? Social Policy and Society, 5(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746405002733

von Soest, T., Luhmann, M., Hansen, T., & Gerstorf, D. (2020). Development of loneliness in midlife and old age: Its nature and correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(2), 388–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000219

Weaver, G. D., Turner, N. H., & O’Dell, K. J. (2000). Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping among women recovering from addiction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 18(2), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(99)00031-8

Wilsnack, S. C., Klassen, A. D., Schur, B. E., & Wilsnack, R. W. (1991). Predicting onset and chronicity of women’s problem drinking: A five-year longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 81(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.81.3.305

Wootton, R. E., Greenstone, H. S. R., Abdellaoui, A., Denys, D., Verweij, K. J. H., Munafò, M. R., & Treur, J. L. (2021). Bidirectional effects between loneliness, smoking and alcohol use: Evidence from a Mendelian randomization study. Addiction, 116(2), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15142

Zebhauser, A., Hofmann-Xu, L., Baumert, J., Häfner, S., Lacruz, M. E., Emeny, R. T., Döring, A., Grill, E., Huber, D., Peters, A., & Ladwig, K. H. (2014). How much does it hurt to be lonely? Mental and physical differences between older men and women in the KORA-Age Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(3), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3998

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all study participants. Further, the authors thank the staff involved in the planning, organization, and conduct of the GHS, KORA, and SHIP study.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. GESA is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; Nr.01GL1718A). The Gutenberg Health Study (GHS) is funded through the government of Rhineland-Palatinate (“Stiftung Rheinland-Pfalz für Innovation”, contract AZ 961–386261/733), the research programs “Wissen schafft Zukunft” and “Center for Translational Vascular Biology (CTVB)” of the Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz, and its contracts with Boehringer Ingelheim, and PHILIPS Medical Systems, including an unrestricted grant for the Gutenberg Health Study. PSW is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF 01EO1503). PSW and TM are PI of the German Center for Vascular Research (DZHK). The KORA study was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and by the State of Bavaria. SHIP is part of the Community Medicine Research net of the University of Greifswald, which is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103, and 01ZZ0403), the Ministry of Cultural Affairs and the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Manfred Beutel, Elmar Braehler, Georg Schomerus, Harald Binder, Johannes Kruse and Karl-Heinz Ladwig; Formal analysis and investigation: Hamimatunnisa Johar and Seryan Atasoy; Writing–original draft preparation: Hamimatunnisa Johar; Writing–review and editing: Hamimatunnisa Johar, Seryan Atasoy and Karl-Heinz Ladwig; Proofread and editing: all authors; Funding acquisition: Manfred Beutel, Elmar Braehler, Georg Schomerus, Harald Binder, Johannes Kruse and Karl-Heinz Ladwig; Project administration/management: Hamimatunnisa Johar, Seryan Atasoy, Daniela Zöller, Toni Fleischer and Danielle Otten.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. All three cohort studies included in the GESA consortium were approved by ethic committees.

GHS: The GHS and its procedure were approved by the ethics committee of the Statutory Board of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany (approval at 22.3.2007, latest update 20.10.2015, reference no. 837.020.07). Participation was voluntary and written informed consent was obtained from each subject upon entry into the study.

KORA: All study methods were approved by the ethics committee of the Bavarian Chamber of Physicians, Munich (F4 and FF4: reference no. 06068).

SHIP: This institutional ethics committee of the University Medicine Greifswald evaluated the study, design and instruments and testified its compliance with ethical requirements (reference no. BB 39/08).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Johar, H., Atasoy, S., Beutel, M. et al. Gender-Differential Association Between Loneliness and Alcohol Consumption: a Pooled Analysis of 17,808 Individuals in the Multi-Cohort GESA Consortium. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01121-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01121-y