Abstract

Within the Compensatory Internet Use Theory (CIUT) framework, online activities may compensate for psychosocial problems. However, those who attempt to satisfy their needs or mitigate their fears via Social Networking Sites (SNSs) may be at heightened risk for problematic use of SNSs (PSNSU), especially in cases when these fears have an interpersonal basis, and the individual effectively finds online social support. The current study hypothesizes that interpersonally-based fears (i.e., fear of no mattering, fear of intimacy, and fear of negative evaluation) predict PSNSU, and online social support moderates these associations. Four hundred and fifty Italian participants (Mage = 27.42 ± 7.54; F = 73.5%) take part in the study. As examined by path analysis, the three interpersonal fears were positively associated with PSNSU, and online social support significantly moderates the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and PSNSU. The model accounted for 19% of the variance of PSNSU and showed good fit indices. The associations' strengths decrease as age increases. Overall, the current study finds further support for the theory that motivations need to be taken into account when it comes to internet uses (i.e., CIUT) and extends our understanding by highlighting that online social support might reinforce the link between the fear of being negatively evaluated and PSNSU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social Networking Sites (SNSs) are gaining traction with over two billion users. In the excessive or problematic form, SNSs use is connected with various mental health symptoms, most notably depression and anxiety (Hussain & Griffiths, 2018). Problematic Social Networking Sites Use (PSNSU) has been defined as “being overly concerned about SNSs, to be driven by a strong motivation to log on to or use SNSs, and to devote so much time and effort to SNSs that it impairs other social activities, studies/job, interpersonal relationships, and/or psychological health and well-being” (Andreassen & Pallesen, 2014, p. 4054). The impact and the high prevalence of PSNSU (for a meta-analytic review, see Cheng et al., 2021) prompted an investigation of the contributing factors to this problematic behavior in the last three decades (Griffiths, 1996; Young, 1999).

The Compensatory Internet Use Theory (CIUT; Kardefelt-Winther, 2014) is a well-cited conceptualization to explain PSNSU (Akbari et al., 2021). Accordingly, PSNSU might be a compensating activity resulting from unfulfilled demands in the actual world, and positive reinforcement arises when unmet demands are fulfilled. For example, when individuals are lonely and isolated, they may feel compelled to satisfy their need for belonging, affection, and receiving social support through social networking sites. Similarly, individuals who experience high levels of shame spend more time on SNSs to meet their social needs and this is positively associated with PSNSU (Casale & Fioravanti, 2017).

Starting from the CIUT and associated empirical evidence, the current paper focuses on the relevance that fears with an interpersonal basis—including fear of negative evaluation, fear of intimacy, and fear of no mattering—might have with respect to PSNSU. That is, within the CIUT perspective, the current study conceptualizes PSNSU as a compensatory behavior stemming from certain interpersonally-based fears, as people prone to fears on an interpersonal basis might be driven toward online social networks as a method to meet unfulfilled psychosocial needs.

According to the hyper-personal perspective (Walther, 1996), face-to-face interaction and communication through social networking sites differ in ways that may appeal to those with interpersonally-based fears because evaluative verbal and nonverbal cues (potentially relevant in face-to-face interactions) are less present when communicating through social networking sites. This type of interaction allows greater control over self-presentation, which may create a sense of security, allowing people to feel free in their online interpersonal interactions than in face-to-face interactions. In keeping with this perspective, previous studies have identified some characteristics of online communicative services that explain why they are especially appealing to people trying to cope with psychosocial difficulties, including the reduction of nonverbal cues and the temporal flexibility offered by the computer-mediated interaction (Schouten et al., 2007; Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). Below we describe these fears in more detail, and we present previous findings on their link with PSNSU—if any.

The fear of negative evaluation is defined as “apprehension about others’ evaluations, distress over their negative evaluations, avoidance of evaluative situations, and the expectations that others would evaluate oneself negatively” (Watson & Friend, 1969; p. 449). Based on this definition, people who are more afraid of negative feedback may perceive online SNSs as safer than the real world since they have more control over their self-disclosure. In accordance with the previously mentioned hyper-personal perspective, the virtual environment allows individuals with high levels of this fear to control better how they are evaluated and how its effect is tempered (Kelly et al., 2020). However, being engaged in a controllable and safer environment might reinforce their SNSs use. Indeed, previous findings have already shown that fear of being negatively evaluated is positively associated with PSNSU (Ali et al., 2021; Casale et al., 2014; Zsido et al., 2020).

The fear of intimacy can be defined as “the inhibited capacity of an individual, because of anxiety, to exchange thoughts and feelings of personal significance with another individual who is highly valued” (Descutner & Thelen, 1991, p. 219). Early research found that people with high fear of intimacy are less satisfied in relationships (Greenfield & Thelen, 1997), less comfortable with self-disclosure (Descutner & Thelen, 1991; Doi & Thelen, 1993), end relationships sooner (Thelen et al., 2000), and seem to have a limit to how vulnerable they will allow themselves to be (Fritscher, 2021). That vulnerability might be mitigated in computer-mediated interactions since online communication offers fewer nonverbal cues (such as facial expressions in text-based messaging) and higher anonymity. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have focused their attention on the link between fear of intimacy and PSNSU. However, previous results have shown that both anxious and avoidant attachment—which are by definition characterized by fear of intimacy (Lyvers et al., 2021)—are strongly linked to PSNSU (for a systematic review, see D’Arienzo et al., 2019). SNSs use might help these individuals to self-disclose and regulate their level of vulnerability more effectively by maintaining the connection to others while being physically distant from them. Thus, the need for belongingness and social support might be met, reinforcing SNSs use.

The fear of no mattering to other people is both a need and a mode that entails not feeling one's significance to others, and it includes a sense of dependence on others, a sense of not being important and significant to others, and a sense of not getting attention from others (Flett, 2018; Flett et al., 2022). A recent commentary article by Casale and Flett (2020) considered how mattering might be a psychological resource that should prove very protective in terms of buffering the anxiety that lead individuals to use SNSs. Conversely, people who do not feel a sense of being seen and heard by others and do not feel like they count to other people may use SNSs to get social attention and a sense of importance. However, positive reinforces might exacerbate the SNSs use. To our knowledge, no previous studies have empirically examined the link between fear of no mattering and PSNSU.

In the current study, we argue that individuals who fear intimacy, others’ judgment, and do not matter to others should be more motivated than their counterparts to use online social networks because they feel safer, more confident, and more comfortable with online interpersonal interactions and relationships than with traditional face-to-face social activities (Caplan, 2003). In other words, these fears might put individuals at risk of seeking out communicative channels (such as SNSs) that minimize potential costs. However, we also argue that the risk of developing PSNSU might also depend on the quality of the relationships individuals find in the online environment. Based on the framework of the CIUT, it is plausible to suppose that individuals whose social needs are not being met because of their interpersonal fears are more vulnerable to becoming reliant on SNSs when they effectively find online social support. Interestingly, the support individuals obtain through online settings has been scarcely investigated as a potential moderating variable in the link between interpersonally-based fears and PSNSU. The few studies available show that social support provided through SNS is positively linked with the continued use of SNSs and is a significant positive predictor of PSNSU (e.g., Lin et al., 2018; Liu & Ma, 2018), but they did not consider its interaction with low social skills or interpersonal fears. In keeping with the CIUT, we speculate that getting social support in the "online format" may moderate the links between interpersonally-based fears and PSNSU. That is, receiving and giving online support might increment the risk of PSNSU for those experiencing high levels of interpersonally-based fears as some compensation for one’s social fears and needs are found.

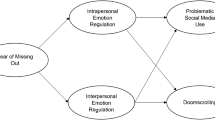

The present study aimed to build upon previous research by 1) focusing the attention on the specific contribution of interpersonal fears in predicting problematic SNSs use by also taking into consideration previous unexplored associations (i.e., the fear of intimacy and the fear of no mattering); 2) including the investigation of the potential moderating role of online social support in the relationship between interpersonal fears and problematic SNSs use. In detail, the following hypotheses were derived (Fig. 1):

-

(1)

Fear of being negatively evaluated, fear of intimacy, and fear of no mattering will be positively correlated with PSNSU;

-

(2)

Online social support will moderate the link between these three fears and PSNSU. At high levels of online social support, high fear of no mattering, fear of intimacy, and fear of negative evaluation would predict high PSNSU more strongly than at low levels of online social support.

As previous studies have shown that women and younger people report higher levels of PSNSU (Su et al., 2020), the statistical model will be adjusted for age and gender.

Method

Participants and procedure

An a priori analysis was conducted using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) to determine the sample size adequacy. The results indicated that 160 participants would be necessary to achieve a power of 0.95 by assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) and an alpha level of 0.05.

A sample of 450 participants (Mage = 27.42 ± 7.54; age range = 15–67) agreed to participate in the study. The majority of the sample was composed of females (73.5%). Regarding educational qualifications, 37.1% of the sample reported having a bachelor's degree, 33.8% a high school diploma, 19.8% a master's degree, 7.8% a higher qualification (e.g., Ph.D.), and 1.6% a middle school diploma. Regarding participants' sentimental status, 40.4% were single, 36.7% reported having a non-cohabiting partner, 22.7% had a cohabiting partner, and 0.2% were divorced. The majority of the sample were students (41.8%), followed by workers (29.3%), working students (23.8%), and unoccupied (5.1%).

Participants were recruited using advertisements on social network groups and were informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous and that confidentiality was guaranteed. The inclusion criterion for participating in the study were (i) being at least 14 years old and (ii) being a social network sites user. A web link directed the participants to the study website. The first page of the study website explained the general purpose: "To investigate the association between certain fears and the Problematic Social Network Sites Use." Participants were then directed, if consenting to participate in the study, to a second page containing demographic questions about themselves and their use of social networks (e.g., "How many hours do you spend per week using SNSs?"; "Which SNSs do you use the most?") and the self-report questionnaires. No remunerative rewards were given.

Measures

Demographic information

Demographic data were collected, including respondents' age (in years), gender, education, sentimental and occupational status. Regarding information about SNSs use, it was asked to indicate how many hours per week they use social networks and which SNSs they use the most.

Fear of Intimacy

Fear of Intimacy was assessed using the five-item subscale of Past relationships fear of intimacy retrieved from the Italian version (Senese et al., 2020) of the Fear of Intimacy Scale (FIS; Descutner & Thelen, 1991). Participants were asked to respond on a 5-points Likert scale (1 = "almost never true" to 5 = "almost always true"). An example item is "I have held back my feelings in previous relationships." Higher scores indicate higher fear of intimacy. The Italian version of the FIS showed good psychometric properties in the full scale and its subscales (Senese et al., 2020). In the current study, McDonald’s Omega was 0.67.

Fear of Negative Evaluation

Fear of negative evaluation was assessed using a preliminary Italian version of the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation-II (BFNE-II; Carleton et al., 2007), a 12-item version of the original fear of negative evaluation scale (Watson & Friend, 1969). A sample item is "I am afraid others will not approve me." Participants were asked to rate their level of fear on a 5-points Likert scale (from 1 = not at all characteristic of me to 5 = completely characteristic of me). Higher scores indicate higher fear of being judged by others. In the current study, McDonald’s Omega was 0.96.

Fear of no mattering

Fear of no mattering was assessed with the Italian version (Giangrasso et al., 2021) of the Anti-Mattering Scale (AMS; Flett, 2018). An example item is "How often have you been treated in a way that makes you feel like you are insignificant?". Participants were asked to respond using a four-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all; 4 = A lot). Higher scores indicate greater perceived anti-mattering. The Italian AMS showed a one-factor solution and good internal consistency (Giangrasso et al., 2021). In the current study, McDonald’s Omega was 0.86.

Online social support

Online social support was measured using a modified version of the 14-item Facebook Measure of Social Support (FMSS; Mccloskey et al., 2015). Specifically, items were adapted to be extended to all social networking sites instead of to Facebook only. An item sample is "If I needed information about something, I could post it on Social Networks, and I'd get the information I need." The scale was translated from English into Italian according to the recommendations of the International Test Commission (2005). Participants rated their agreement with each of the 14 items on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of social support from SNSs. The original FMSS showed good internal consistency. In the current study, McDonald’s Omega was 0.80.

Problematic Social Network Sites Use

PSNSU was measured using the Italian version (Monacis et al., 2017) of the 6-items Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS; Andreassen et al., 2016). The BSMAS contains six items reflecting core addiction elements (i.e., salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse). Each item deals with experiences within 12 months and is answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often). A sample item is: "How often during the last year have you felt an urge to use social media more and more?". Higher scores indicate a higher level of problematic social networking sites use. The BSMAS showed good reliability and validity for the assessment of PSNSU, and the Italian version has also demonstrated good psychometric properties (see also Monacis et al., 2020). In the current study, McDonald’s Omega was 0.82.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations between the study variables were computed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The pattern of relationships specified by our hypothesized model (Fig. 1) was tested through path analysis, using IBM SPSS Amos version 25 with the Robust Maximum Likelihood (RML) estimation method. All path analysis assumptions were met. In our model, fear of no mattering, fear of intimacy, fear of negative evaluation were the independent variables, online social support was the moderator, and PSNSU was the dependent variable. Age and gender were included as covariates of the dependent variable. Prior to all analyses, all measures were mean-centered (Aiken & West, 1991). We first tested the full model and then removed step-by-step path coefficients not significant at the 5% level to select the most plausible model. To evaluate the model's goodness of fit, we considered the χ2 (and its degrees of freedom and p-value), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI—Bentler, 1995) "close to" 0.95 or higher (Hu & Bentler, 1999), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA—Steiger, 1990) less than 0.08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993).

Results

A Harman one-factor analysis was conducted to detect common method bias. Since no single factor emerged and did not account for the majority of the variance in the data, common method variance is not a pervasive issue in the current study (Chang et al., 2010). Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients among the study variables are reported in Table 1. The results followed the expected pattern so that fear of intimacy, fear of negative evaluation, fear of no mattering, and online social support were positively related to PSNSU. Likewise, fear of intimacy, fear of negative evaluation, and fear of no mattering were significantly and positively associated with online social support.

Path analysis

A first version of the model was tested, including all the variables of interest. However, several path coefficients were not significant at the p < 0.05 level and were removed step by step (i.e., the path between gender and PSNSU; the path between the interaction between online social support and fear of intimacy and PSNSU; the path between the interaction between online social support and fear of no mattering and PSNSU). Therefore, the final model included all the significant paths depicted in Fig. 2. In this model, fear of no mattering (β = 0.10; p = 0.03), fear of intimacy (β = 0.17; p < 0.001), and fear of negative evaluation (β = 0.26; p < 0.001) were positively associated with PSNSU. Only, online social support significantly moderates (β = 0.15; p < 0.001) the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and PSNSU. Regarding control variables, age was negatively linked (β = -0.11; p = 0.008) to PSNSU. The model accounted for 19% of the variance of PSNSU and showed good fit indices: χ2 = 15.25, df = 6, p = 0.02; RMSEA [90%CI] = 0.05[0.02-0.95], CFI = 0.97.

Discussion

The current study explored the interrelations between three interpersonally-based fears with PSNSU in light of CIUT. As hypothesized, fear of no mattering, fear of intimacy, and fear of negative evaluation were positively associated with PSNSU. The present study confirmed the already known significant effect of social anxiety/fear of negative evaluations on PSNSU (e.g., Ali et al., 2021). Previous studies have suggested that social anxiety affects PSNSU through typical maladaptive cognitive-emotion regulation strategies, including self-blaming, rumination, and catastrophizing (Zsido et al., 2021). This would suggest that the compulsive use of SNSs might be partially motivated by the motivation to escape negative feelings. Another psychologically plausible explanation is that people who fear being judged prefer online social interactions as SNSs allow greater control over self-presentation (Casale & Fioravanti, 2017), thus representing an environment that offers the opportunity to ameliorate one’s self-image and increase the self-perception of being more successful in a sort of social liberation (Akhter et al., 2021). Yet, individuals might find themselves stuck in an effort to improve their personal and social image through computer-mediated communication, as our results seem to highlight a link between the fear of negative evaluation and PSNSU.

Beyond confirming previous findings, the current study adds to the previous literature by focusing on two less investigated interpersonally-based fears in this field, i.e., the fear of no mattering and the fear of intimacy. Regarding the former, recent studies suggest that individuals who feel like they do not matter to others perceive deficits in meeting key psychological needs and show high levels of depression, social anxiety, and loneliness (Flett et al., 2022). Our findings extend these previous results by showing that feelings of not mattering might also be linked to PSNSU. According to CIUT, people who are apprehensive about others’ evaluations and do not feel like they count on others will need to find ways to stay connected with others. They might use SNSS to satisfy their need of belongingness. Persons who use SNSs to alleviate their worry about not belonging might get a sense of significance, inclusion, and importance by gaining more followers, likes, and online friends.

Similarly, people with a fear of intimacy can determine how much to get close with others while receiving some intimacy through interactions within SNSs. As already briefly discussed, alternative explanations for these positive associations include the possibility that these individuals use SNSs to alleviate their negative feelings (rather than to satisfy their unmet needs). Indeed, previous evidence suggests that individuals who have problems with emotional regulation are more likely to engage in online social networking in an attempt to escape from, or minimize, negative moods and/or try to alleviate distressing feelings (for a systematic review, see Gioia et al., 2021). Future studies might want to investigate whether interpersonally-based fears are more strongly linked to PSNSU than they are with other technological addictions (e.g., problematic smartphone use, PSU). Stronger associations with PSNSU would give further support to CIUT (e.g., individuals high on social anxiety will use SNSs to socialize, which may put them at increased risk of compulsive use and subsequent conflicts at home/work/school due to their engagement with social networks). Conversely, similar associations in strength would support explanations derived from the field of substance use, including that addictive behaviors should be seen as avoidance strategies (i.e., escape from or downregulate negative affects).

The present study also hypothesized that the association between these fears and PSNSU would have been stronger at high levels of online social support. We speculated that the support individuals obtain through online settings might increase the effect of interpersonally-based fears on PSNSU. Our hypothesis was partially supported in that online social support only moderated the association between fear of negative evaluation and PSNSU. The significant moderating role of online social support in the association between fear of negative evaluation and PSNSU may be due to the that these people may increment their use of social networking sites if they satisfy online their unmet needs (i.e., social support) within an environment that they have control over how other people see them, tempering the level of judgment and its impact. This is in line with Kelly et al. (2020) that having safer spaces can increase the use of the mentioned sites.

Conversely, it might be the case that people with a fear of no mattering and fear of intimacy may use social networking sites due to other needs rather than receiving social support. It might be speculated that these individuals are a bit pessimistic about the ability of the mentioned sites to fulfill their need for belonging, a sense of significance, and importance. Conversely, they may use social networking sites to cope with real-world distress and avoid what they have been experiencing, as already suggested above.

Limitations

The study's cross-sectional nature may not allow concluding causality, and the temporality of the findings needs to be tested using multi waves points data gathering. We cannot rule out that spending much time on SNSs might increment interpersonally-based fears and a general sense of disconnection from others. Moreover, healthy young adult subjects were enrolled. Thus, the results cannot be generalized to adolescents, older adults, and clinical populations.

Conclusions

The current study findings shed light on previously unexplored potential SNSs’ use motivations. People with a fear of no mattering might use social networking sites to receive some attention and a sense of significance and importance; people with the fear of intimacy might be more willing to engage in online social interactions and more comfortable with online self-disclosure, and people with the fear of negative evaluation might consider computer-mediated communication as a safer space to get in touch with other people. Since SNSs are by definition platforms to communicate with others, research on interpersonally-based fears should be continued to develop knowledge on the key processes leading to PSNSU compared to pathways toward other addictive behaviors.

Materials and/or Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Akbari, M., Seydavi, M., Palmieri, S., Mansueto, G., Caselli, G., & Spada, M. M. (2021). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and internet use: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(4), 879–900. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00083

Akhter, S., Islam, M. H., Haider, S. K. U., Ferdous, R., & Runa, A. S. (2021). Moderating effects of gender and passive Facebook use on the relationship between social interaction anxiety and preference for online social interaction. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 32, 719–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2021.1955801

Ali, F., Ali, A., Iqbal, A., & Ullah Zafar, A. (2021). How socially anxious people become compulsive social media users: The role of fear of negative evaluation and rejection. Telematics and Informatics, 63, 101658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101658

Andreassen, C., & Pallesen, S. (2014). Social network site addiction - an overview. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4053–4061. https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990616

Andreassen, C. S., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160

Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

Caplan, S. E. (2003). Preference for online social interaction: A theory of problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being. Communication Research, 30(6), 625–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650203257842

Carleton, R. N., Collimore, K. C., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation: Construct validity of the BFNE-II. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.010

Casale, S., & Fioravanti, G. (2017). Shame experiences and problematic social networking sites use: An unexplored association. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 14(1), 44–48.

Casale, S., Fioravanti, G., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2014). From socially prescribed perfectionism to problematic use of internet communicative services: The mediating roles of perceived social support and the fear of negative evaluation. Addictive Behaviors, 39(12), 1816–22.

Casale, S., & Flett, G. L. (2020). Interpersonally-Based Fears During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Reflections on the Fear of Missing Out and the Fear of Not Mattering Constructs. Clinical neuropsychiatry, 17(2), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.36131/CN20200211

Chang, S.-J., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the Editors: Common Method Variance in International Business Research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 178–184.

Cheng, C., Lau, Y. C., Chan, L., & Luk, J. W. (2021). Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addictive Behaviors, 117, 106845. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2021.106845

D’Arienzo, M. C., Boursier, V., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Addiction to Social Media and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(4), 1094–1118. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11469-019-00082-5

Descutner, C. J., & Thelen, M. H. (1991). Development and validation of a Fear-of-Intimacy Scale. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3(2), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.3.2.218

Doi, S. C., & Thelen, M. H. (1993). The Fear-of-Intimacy Scale : Replication and extension. Psychological Assessment, 5(3), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.3.377

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Flett, G. L., Nepon, T., Goldberg, J. O., Rose, A. L., Atkey, S. K., & Zaki-Azat, J. (2022). The Anti-Mattering Scale: Development, Psychometric Properties and Associations with Well-Being and Distress Measures in Adolescents and Emerging Adults. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 40(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829211050544

Flett, G. L. (2018). The psychology of mattering: Understanding the human need to be significant. Academic Press.

Fritscher, L. (2021). Fear of Intimacy: Signs, Causes, and Coping Strategies. Retrieved 26 December 2021, from https://www.verywellmind.com/fear-of-intimacy-2671818

Giangrasso, B., Casale, S., Fioravanti, G., Flett, G. L., & Nepon, T. (2021). Mattering and Anti-Mattering in Emotion Regulation and Life Satisfaction: A Mediational Analysis of Stress and Distress During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 40(1), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829211056725

Gioia, F., Rega, V., Boursier, V. (2021). Problematic Internet Use and Emotional Dysregulation Among Young People: A Literature Review. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 572(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.36131/cnfioritieditore20210104

Greenfield, S., & Thelen, M. (1997). Validation of the fear of intimacy scale with a lesbian and gay male population. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 14(5), 707–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407597145007

Griffiths, M. D. (1996). Internet addiction: an issue for clinical psychology? Clinical Psychology Forum, 97, 32–36. Nottingham Trent University.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hussain, Z., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Problematic social networking site use and comorbid psychiatric disorders: A systematic review of recent large-scale studies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 686–695. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00686

International Test Commission. (2005). International Guidelines on Computer-Based and Internet Delivered Testing. www.intestcom.org

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

Kelly, L., Keaten, J. A., & Millette, D. (2020). Seeking safer spaces: The mitigating impact of young adults’ Facebook and Instagram audience expectations and posting type on fear of negative evaluation. Computers in Human Behavior, 109, 106333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106333

Lin, M. P., Wu, J. Y. W., You, J., Chang, K. M., Hu, W. H., & Xu, S. (2018). Association between online and offline social support and internet addiction in a representative sample of senior high school students in Taiwan: The mediating role of self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2018.02.007

Liu, C., & Ma, J. (2018). Development and validation of the Chinese social media addiction scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 134, 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2018.05.046

Lyvers, M., Pickett, L., Needham, K., & Thorberg, F. A. (2021). Alexithymia, Fear of Intimacy, and Relationship Satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 1-22.https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211010206

McCloskey, W., Iwanicki, S., Lauterbach, D., Giammittorio, D. M., & Maxwell, K. (2015). Are Facebook “friends” helpful? Development of a Facebook-based measure of social support and examination of relationships among depression, quality of life, and social support. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(9), 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0538

Monacis, L., De Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D., & Sinatra, M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.023

Monacis, L., Griffiths, M. D., Limone, P., Sinatra, M., & Servidio, R. (2020). Selfitis behavior: Assessing the Italian version of the Selfitis Behavior Scale and its mediating role in the relationship of dark traits with social media addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165738

Schouten, A. P., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2007). Precursors and underlying processes of adolescents’ online self-disclosure: Developing and testing an “Internet-attribute-perception” model. Media Psychology, 10(2), 292–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701375686

Senese, V. P., Miranda, M. C., Lansford, J. E., Bacchini, D., Nasti, C., & Rohner, R. P. (2020). Psychological maladjustment mediates the relation between recollections of parental rejection in childhood and adults’ fear of intimacy in Italy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(6), 1968–1990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520912339

Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4

Su, W., Han, X., Yu, H., Wu, Y., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, 106480. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2020.106480

Thelen, M. H., Vander Wal, J. S., Thomas, A. M., & Harmon, R. (2000). Fear of intimacy among dating couples. Behavior Modification, 24(2), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445500242004

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 48(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020

Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-Mediated Communication: Impersonal, Interpersonal, and Hyperpersonal Interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365096023001001

Watson, D., & Friend, R. (1969). Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33, 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0027806

Young, K. S. (1999). Internet addiction: Symptoms, evaluation, and treatment innovations in clinical practice (Vol. 17). Professional Resource Press.

Zsido, A. N., Arato, N., Lang, A., Labadi, B., Stecina, D., & Bandi, S. A. (2020). The connection and background mechanisms of social fears and problematic social networking site use: A structural equation modeling analysis. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113323

Zsido, A. N., Arato, N., Lang, A., Labadi, B., Stecina, D., & Bandi, S. A. (2021). The role of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and social anxiety in problematic smartphone and social media use. Personality and Individual Differences, 173, 110647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110647

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Firenze within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Silvia Casale: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, supervision Mehdi Akbari: writing original draft; Sara Bocci Benucci: conceptualization, resources; Mohammed Seydavi: writing original draft; Giulia Fioravanti: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University’s Research Ethics Board and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

Data

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflict of Interests

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casale, S., Akbari, M., Bocci Benucci, S. et al. Interpersonally-Based Fears and Problematic Social Networking Site Use: The Moderating Role of Online Social Support. Int J Ment Health Addiction 22, 995–1007 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00908-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00908-9