Abstract

Adolescents who have experienced adversity have an increased likelihood of using substances. This study examined if individual-, family-, school-, and community-level protective factors were associated with a decreased likelihood of substance use. Data from the Well-Being and Experiences Study (the WE Study) collected from 2017 to 2018 were used. The sample was adolescents aged 14 to 17 years (N = 1002) from Manitoba, Canada. Statistical methods included descriptive statistics and logistic regression models. The prevalence of past 30-day substance use was 20.5% among boys and 29.2% among girls. Substance use was greater among adolescent girls compared to boys. Protective factors associated with an increased likelihood of not using substances included knowing culture or language, being excited for the future, picturing the future, sleeping 8 to 10 h per night (unadjusted models only), participating in non-sport activity organized by the school, having a trusted adult in the family, frequent hugs from parent, parent saying “I love you” (unadjusted models only), eating dinner together every day, mother and father understanding adolescent’s worries and problems, being able to confide in mother and father, feeling close to other students at school, having a trusted adult at school, feeling a part of school, having a trusted adult in the community (unadjusted models only), volunteering once a week or more, and feeling motivated to help and improve one’s community. Knowledge of protective factors related to decreased odds of substance use may help inform strategies for preventing substance use and ways to foster resilience among adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adolescence is an important developmental period and a time when experimentation with substances often begins. Previous research has shown that the prevalence of substance use (i.e. tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and illegal drugs) is high among adolescents and ranges from 16 to 50% across studies depending on respondents’ age, type of substance, and timeframe of use (Afifi, Taillieu, et al., 2020b; Johnston et al., 2017; Turner et al., 2018). Preventing substance use during adolescence is important because it has been shown to be associated with a broad range of poor outcomes including overdoses, vehicular crashes, long-term cognitive impairment, poor academic and vocational outcomes, suicide attempts, and psychiatric comorbidity (Hammond et al., 2020; Schulte & Hser, 2013). In addition, preventing substance use during adolescence may help to prevent substance use problems in adulthood (Liang & Chikritzhs, 2015) and possibly decrease the likelihood of numerous associated poor outcomes such as sexually transmitted infections (Dembo et al., 2009), unintended pregnancies (Carroll Chapman & Wu, 2013), mental disorders and suicidality (Hengartner et al., 2020), and physical health problems (Volkow et al., 2014). Studies involving adult and adolescent samples have also shown that child maltreatment and other adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as bullying/peer victimization, spanking, parental divorce or separation, parental mental disorders, and parental problems with substances are associated with significantly increased likelihood of substance use (Afifi et al., 2014, 2017; Afifi, Taillieu, et al., 2020b; Anda et al., 1999). Protective factors at the individual, family, school, and community levels may decrease the likelihood of substance use among adolescents with a history of ACEs; however, to date, little is known about what factors might be protective and potentially foster resilience among this high-risk group.

A protective factor is defined as a trait that contributes to resilience or influences, modifies, ameliorates, or alters an individual response in a positive way following adversity (Masten, 2013). Various definitions of resilience exist (Herrman et al., 2011), but the term generally refers to the ability to maintain or regain mental health despite adversity (Wald et al., 2006). Protective factors may include individual-level factors or personal characteristics; family-level protective factors, such as family resources or supportive relationships; and school- or community-level protective factors such as peer relationships, social support from schools, teachers, or individuals in the community, among others (Afifi & MacMillan, 2011). Several studies have examined individual- and family-level protective factors related to resilience following child maltreatment, but fewer studies have included community-level protective factors (Afifi & MacMillan, 2011).

Protective factors found to be associated with improved mental health among adolescents with a child maltreatment history include being physically active, positive coping skills, positive self-esteem, internal locus of control, supportive parent and family relationships, and positive school and community experiences (Cheung et al., 2017, 2018). These studies of protective factors focused on mental disorders (including alcohol and drug abuse/dependence), suicidal ideation, and perceived mental health, but did not examine substance use alone. Some studies have identified protective factors related to decreased substance use among adolescents; these factors include the quality of parent-child attachment, church attendance, intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment, strong ethnic identity, peer relationships, school connectedness, and physical activity, among others (Lardier et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Pittenger et al., 2018; Unger et al., 2020). However, these studies did not look specifically at protective factors among adolescents who have experienced ACEs. This high-risk group of adolescents may have specific protective factors that are important to identify in determining ways to prevent substance use.

Importantly, variability in poor outcomes following childhood adversity has been noted (Afifi & MacMillan, 2011), yet why some children appear to be more resilient following adversity is not well understood. It may be that despite experiencing adversity, these individuals have certain protective factors that help them to overcome risk and may be related to better outcomes in adolescence and over time (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Fergus and Zimmerman’s (2005) protective resilience model theorizes that a protective factor may reduce the negative impact of the risk (e.g. adversity) on an outcome. Applied to the current research, some individuals may experience ACEs but still maintain protective factors, which could be related to decreased likelihood of substance use among adolescents.

The objectives for the current study were to (1) describe any past 30-day substance use as well as nicotine use, binge drinking, being drunk/intoxicated, and cannabis use among a community sample of adolescents; (2) examine the relationships between individual ACEs and any past 30-day substance use among adolescents; and (3) determine if individual-, family-, school-, and community-level factors are protective and related to increased likelihood of not using substances in the past 30 days among those with an ACEs history.

Method

Data and Sample

Baseline data (wave 1) from the Well-Being and Experiences Study (the WE Study) was used, which includes adolescents (N = 1002; aged 14 to 17 years) and their parents/caregivers from Manitoba, Canada. The current study only used adolescent data, which was collected between July 2017 and October 2018. Parent/caregiver and adolescent pairs were recruited by contacting the parent using random digit dialing (21%) and convenience sampling methods (79%) such as referrals. From those contacted using random digit dialing, 83% indicated an interest in participating in the study. 97% of the 83% interested in participating were not eligible to participate because an adolescent aged 14 to 17 years old did not reside in the household. Of those who were eligible, 63% consented and completed the survey. No distributional differences in the data were noted based on sampling method for adolescent data on age, grade, ethnicity, and most ACEs. The Forward Sortation Area from postal codes was used to ensure the sample was closely representative of Winnipeg, Manitoba, the largest city in the province with a population of approximately 753,700 and surrounding rural areas. As well, data collection was monitored to ensure that the adolescent sample closely resembled the general population with regard to sex, household income, and ethnicity, using the 2017 Statistics Canada census profile (Statistics Canada, 2017). The parent/caregiver considered to be the most knowledgeable of the child was asked to participate. Parents/caregivers and adolescents completed a self-administered questionnaire on a computer at a research facility independently in private rooms. Parents/caregivers were not able to review adolescent responses. Informed consent to participate was provided by both parents/caregivers and adolescents. Parents/caregivers and adolescents were compensated $50 and $30, respectively, for their time and travel expenses. Ethics approval was provided by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Manitoba.

Measures

Adolescent Substance Use

Adolescent past 30-day substance use included cigarette use, alcohol use, and cannabis use. Past 30-day cigarette use was assessed by asking about how many days in the past 30 days did the respondent smoke cigarettes. Past 30-day alcohol use (i.e. binge drinking and intoxication) was assessed with two items measuring how many times in the past 30 days did the respondent: (1) have five or more alcoholic drinks on the same occasion and (2) drink alcohol that made the respondent drunk. For cannabis use, respondents were asked in a typical month on average how often do you use marijuana/hashish (e.g. pot, weed). A dichotomous variable for any past month substance use was also computed.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

ACEs included adolescent experiences of emotional neglect, emotional abuse, exposure to verbal intimate partner violence (IPV), spanking, peer victimization, parental separation or divorce, parental trouble with police, parental gambling, foster care or child protective organization (CPO) contact, household substance use, household mental illness, household poverty, and living in an unsafe neighbourhood. ACEs were selected based on work from a previous study (Afifi, Salmon, et al., 2020a). We could not assess other important ACEs, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, or physical neglect (Felitti et al., 1998), due to requirements of the Health Research Ethics Board related to the Manitoba child welfare mandatory reporting laws.

Emotional neglect was assessed using five items from the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein & Fink, 1998). Emotional abuse was assessed with one item asking how many times a parent or other adult living in their home swore, insulted, or said hurtful or mean things to the respondent in the past 12 months. Responses of once a month to two or more times a day were coded as having experienced emotional abuse. Exposure to verbal IPV was assessed with an item adapted from the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire (CEVQ) asking how often the respondent had ever seen or heard adults say hurtful or mean things to another adult in the home in the past 12 months (Walsh et al., 2008). Responses of once a month to two or more times a day were coded as having been exposed to verbal IPV. Spanking was assessed with one item adapted from the CEVQ (Walsh et al., 2008). The question asked how often the respondent remembered being spanked (with a hand on their bottom/bum) by an adult (or parent or caregiver) in a typical year when they were 10 years old or younger. Responses of two to three times a year to daily were coded as having experienced spanking.

Peer victimization was assessed with seven items measured on a 9-point ordinal scale (ranging from never to everyday) adapted from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Survey (Boyle et al., 2019), the Manitoba Youth Health Survey (Partners in Planning for Healthy Living, 2013), and the National Crime Victimization Survey from the USA (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2014). Respondents were asked how many times in the past 12 months a friend, peer, someone at school, or other young person (not an adult or sibling) had (1) made fun, called them names, or insulted them in person or behind their back (excluding online communications); (2) spread rumours about them in person or behind their back (excluding online communications); (3) pushed, shoved, tripped, or spit on them; (4) said something bad about their sexual orientation or gender identity (excluding online communications); (5) said something bad about their body shape, size, or appearance (excluding online communications); (6) said something bad about their race, culture, or religion (excluding online communications); and (7) bullied, picked on, or said mean things, or threatened them through texting or the Internet. Responses of once a month to everyday on one or more of the seven items were coded as having experienced peer victimization.

Parental separation or divorce was assessed as whether the adolescent’s biological parents had ever separated or divorced (yes or no). Parental trouble with police was assessed as whether a parent or other adult living in the home ever had problems with the police (yes or no). Parental gambling was assessed as whether a parent or other adult living in the adolescent’s home ever had problems with gambling (yes or no). Foster care or CPO involvement included (1) contact with a CPO (e.g. social services, child welfare, children’s aid or the Ministry) due to difficulties at home (yes or no) and/or (2) were placed in a foster home or group home (yes or no). Household substance included whether a parent or other adult living in the respondent’s home ever (1) had problems with alcohol or spent a lot of time drinking or being hung over (yes or no) and/or (2) had problems with drugs (yes or no). Household mental illness was assessed asking whether a parent or other adult living in the respondent’s home ever had mental health problems like depression or anxiety (yes or no). Poverty was assessed with two items that asked whether the respondent’s family ever (1) had run out of money or found it hard to pay for rent or mortgage on their home and/or (2) had run out of money or found it hard to pay for basic necessities like food or clothing. Responses of sometimes, often, or very often to one or both of the items were a proxy indicator for poverty. Perceived neighbourhood safety was assessed with the statement “I feel safe in my community”. Adolescents that strongly disagreed or disagreed were coded as living in an unsafe neighbourhood. A dichotomous variable for any ACE was also computed using any of the 13 ACEs assessed.

Protective Factors

Twenty-eight potential protective factors at the individual, family, school, and community levels were assessed in the WE Study. The precise wording for each of the protective factor items (and response options) is presented in Table 3.

Sociodemographic Covariates

Sociodemographic covariates included sex, age, race/ethnicity (i.e. White, White and other race/ethnicity, other ethnicity/multiracial), total annual household income, and grade.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and logistic regression models were computed to examine the distribution and association of sociodemographic covariates by past 30-day substance use, individual ACEs, and any ACE history. Logistic regression models were first run unadjusted and then adjusted for sociodemographic covariates. The distribution and association between protective factors and past 30-day substance use were then examined. In these models, the past 30-day substance use variable was reverse coded so that model estimates indicate the odds of not using substances in the past 30 days. For these analyses, logistic regression models were also first run unadjusted and then adjusted for sociodemographic covariates.

Results

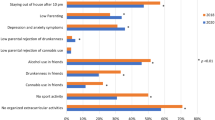

The current sample was 51.7% girls with a mean age of 15.3 years. The distribution of past 30-day substance use, past 30-day cigarette use, past 30-day binge drinking, past 30-day intoxication, and cannabis use in a typical month by sociodemographic variables are presented in Table 1. The prevalence of past 30-day substance use was 25.0% among adolescents (20.5% for boys and 29.2% among girls). Overall, past 30-day substance use was greater among adolescent girls compared to boys and generally increased with age and school grade. No differences in past 30-day substance use were found for household income. No sex differences were found for past 30-day cigarette use and cannabis use in a typical month. Trends for age and grade were similar across substance use types with general trends indicating increasing likelihood of substance use as age and grade increase. Overall few significant findings were noted for household income with decreased odds of any past 30-day cigarette use for household income of $50,000 to $150,000 compared to less than $50,000 and increased odds of any past 30-day binge drinking and intoxication for household income of more than $150,000 compared to less than $50,000. No differences in cannabis use in a typical month were found based on household income. Table 2 presents the prevalence of individual ACEs and the odds of each ACE based on past 30-day substance use. All individual ACEs were associated with past 30-day substance use with the exception of spanking (adjusted odds ratios (AORs) ranged from 1.81 to 4.21). Table 3 presents the findings for individual-, family-, school-, and community-level protective factors associated with increased odds of not using substance use in the past 30-days among adolescents with an ACEs history. Twenty-one of the 28 protective factors examined were associated with increased odds of not using substances in the past 30 days.

Discussion

This study, based on self-report data from a sample of adolescents, identified a number of protective factors at the individual, family, school, and community levels, which are important in determining ways of reducing substance use among adolescents with a history of childhood adversity. In addition, our findings identified that past 30-day substance use was higher in girls compared to boys, which is inconsistent with other work (Zuckermann et al., 2020). Overall, few significant findings for household income were noted in this study. However, it was found that some middle-to-high household income categories ($50,000 to $150,000 compared to less than $50,000) were associated with decreased odds of past 30-day cigarette use, while some higher income categories were associated with increased odds of past 30-day binge drinking and intoxication. In summary, these findings indicate that past 30-day substance use among adolescents did not substantially vary based on household income.

In our study, consistent with previous research, ACEs were associated with an increased likelihood of substance use (Afifi et al., 2014; Afifi, Taillieu, et al., 2020b; Anda et al., 1999; Turner et al., 2018). However, most of this past work is among adult samples examining counts of traditional ACEs, while this work examines an expanded list of individual ACEs in an adolescent sample, although it should also be noted that not all child abuse ACEs could be assessed in this study due to mandatory child protection reporting laws.

It is now well documented that individuals who experience ACEs are more likely to use substances (Afifi et al., 2014; Afifi, Taillieu, et al., 2020b; Anda et al., 1999; Turner et al., 2018). Adolescents with a history of ACEs are an important at-risk group in which to identify protective factors that can help prevent substance use. Developmentally, adolescence is a sensitive period marked by significant neuromaturational processes and a time when experimentation with substances and other risk-taking behaviours is often initiated (Bava & Tapert, 2010). Importantly, findings from the current study do support Fergus and Zimmerman’s (2005) protective resilience model. More specifically, a majority (75%) of the protective factors were associated with better health outcomes, in this case reduced likelihood of substance use, among adolescents who experienced adversity.

At the individual level, programs that provide support and education could be developed that promote adolescents’ ability to identify with their culture or ethnic language with the aim of fostering adolescents’ sense of connection and purpose, although, notably, not identifying with a culture or ethnic language was also protective. This may be not be the same as a loss of culture or language. Further work in this area is warranted. Such programs could also aim to enhance adolescents’ perspective-taking and future-oriented thinking, given that reported excitement for the future and being able to imagine their life 5 years into the future were identified as important protective factors in this study. Interestingly, previous research on adolescent mental health and quality of life has found that optimism for the future, being able to set goals, and plan for future possibilities are important health assets for adolescents that could inform adolescent health promotion strategies (Haggstrom Westberg et al., 2019), while future-oriented thinking has been associated with better reflective decision-making in adolescence (Eskritt et al., 2014).

The protective role of sleeping 8 to 10 h per night (unadjusted models only) is not surprising, given that previous research has documented the relationship between sleep hygiene including hours of sleep and mental health issues, increased risk-taking behaviours, poor decision-making, and impairments in cognitive control among adolescents (Palmer et al., 2018). Although only significant in the unadjusted model, the importance of these protective factors should be communicated to adolescents by their parents and other caregivers to address substance use problems. However, it remains unclear whether informing people of this will lead to actual changes in sleep hygiene.

Findings from the family level may be more applicable to interventions aimed at parents and other caregivers who could have an important role in reducing substance use among adolescents. This study showed that an important protective factor related to adolescent substance use is the quality of the adult-child relationship, and specifically for parents to ensure that the adolescent has a connection with a trusted adult in the family. As well, from a parenting perspective, it may be important for parents to show their affection often to adolescents by hugging them, telling them they are loved, and having a meal together on a regular basis. Notably, telling the adolescent “I love you” five times a week or more was a significant finding in the unadjusted models and became non-significant in adjusted models. This finding was likely due to underpowered models. Further work in this area is warranted.

With regard to family relationships, ensuring positive relationships among parents and adolescents may help to reduce substance use. These findings are consistent with previous research focused on adolescent alcohol use, which has noted that the quality of the parent-child relationship is an important factor associated with adolescent alcohol use initiation, and to some extent binge-drinking (Mathijssen et al., 2014). Specifically, this work identified the importance of mothers and fathers understanding adolescents’ worries and problems, and being able to confide in their mothers and fathers as protective factors. Taken together, this is an important finding that is consistent with previous research demonstrating the significance of a positive parent-child relationship in reducing the risk of adolescent substance use (Moore et al., 2018), yet extends our understanding by elucidating key components of the intimate family system that may be amendable to change. This finding also emphasizes the important and unique role of fathers and male caregivers in the lives of adolescents. As has been noted in previous research, more attention must be put toward understanding the role of paternal engagement and the quality of the father-adolescent relationship as it relates to adolescent mental health and substance use for those with ACEs (Ibrahim et al., 2017).

Interventions aimed at school- and community-level factors may also be useful in reducing substance use among adolescents with an ACEs history. Protective factors identified in this study include feeling close to a student at school, having a trusted adult at school, feeling a part of school, volunteering, and feeling motivated to help and improve their community. It should be noted that disagreeing compared to strongly disagreeing to not feeling close to students at school and feeling part of school were also protective. As well, it should be noted that the effects for community volunteering once a month or a few times a month and the effects for “agree” and “agree strongly” to feeling involved in one’s community may indicate underpowered models and a type II error. Further work in these areas is needed to better understand these findings. Considering these school- and community-level protective factors together, it may be the case that educators, school administrators, and other community leaders are well-positioned to inform and also implement adolescent substance use prevention and intervention strategies. Such strategies should be designed to promote school and community connectedness while strengthening healthy peer-to-peer supports that may reduce the risks of initiation of substance use during this critical period of human development.

Another important finding from the current study was that girls compared to boys were more likely to use substances in the past 30 days. Previous research has found that boys compared to girls are more likely to use substances (Bava & Tapert, 2010). Importantly, recent work has also indicated that girls with a peer victimization history were found to have greater odds of poor health outcomes and increased feelings of sadness and hopelessness (Stewart-Tufescu et al., 2021). It is possible that girls are more likely to use substances as a way to cope. Many studies on adolescent substance use do not examine sex and gender differences. Sex differences may be due to differences in samples or differences in the types of substances included in research, among other factors. Further work on sex and gender differences and substance use among adolescents with a history of childhood adversity is needed.

Limitations of the current study should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although the adolescent sample is similar to the general population sample based on sex, ethnicity, and household income (Statistics Canada, 2017), because the methods for collecting the data were non-random, we have not referred to this sample as representative of the general population. Second, our study was limited to only one geographical area in Canada. Third, due to mandatory child abuse reporting requirements, adolescents were not asked if they had experienced several child maltreatment types including physical abuse and sexual abuse. Fourth, we did not have sufficient statistical power to conduct analyses examining protective factors separately for boys and girls. As well, it was not possible to examine individual substance categories separately, which is a limitation of the study. However, it is important to note that models were adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, and total household income. Finally, there were slight differences in the timeframes of the questions across the different types of substances. For smoking, binge drinking, and being drunk or intoxicated, adolescents were asked about the past 30 days. For cannabis, adolescents were asked about use in a typical month.

Conclusions

It is important to recognize that the findings from this study identify protective factors that may be useful in informing intervention strategies to reduce substance use among adolescents who have experienced ACEs. See Table 4 for a summary of protective factors for consideration when developing and testing interventions strategies for effectively reducing substance use among adolescents with an adversity history. Identifying protective factors during adolescence is of vital importance since this is a sensitive period of human development and most often when risk-taking behaviours, including substance use, commence and continue into adulthood (Liang & Chikritzhs, 2015). Early prevention is critical due to the negative impact substance use can have on a broad range of health outcomes. The identification of protective factors related to decreased odds of substance use among adolescents found in this research is an important first step to informing the development of interventions. Such interventions could be aimed at strengthening or developing these protective factors that increase the likelihood that adolescents with a history of childhood adversity will not engage in substance use. Such interventions would then require evaluation to determine if they are effective in reducing or preventing substance use among adolescents.

Abbreviations

- AORs:

-

Adjusted odds ratios

- ACEs:

-

Adverse childhood experiences

- CPO:

-

Child protective organization

- CEVQ:

-

Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire

- CTQ:

-

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- The WE Study:

-

The Well-Being and Experiences Study

References

Afifi, T. O., Ford, D., Gershoff, E. T., Merrick, M., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Ports, K. A., MacMillan, H. L., Holden, G. W., Taylor, C. A., Lee, S. J., & Peters Bennett, R. (2017). Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 71, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.014

Afifi, T. O., & MacMillan, H. L. (2011). Resilience following child maltreatment: A review of protective factors. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(5), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371105600505

Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M., Taillieu, T., Cheung, K., & Sareen, J. (2014). Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(9), E324–E332. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.131792

Afifi, T. O., Salmon, S., Garces, I., Struck, S., Fortier, J., Taillieu, T., Stewart-Tufescu, A., Asmundson, G. J. G., Sareen, J., & MacMillan, H. L. (2020a). Confirmatory factor analysis of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among a community-based sample of parents and adolescents. BMC Pediatrics, 20, 178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02063-3

Afifi, T. O., Taillieu, T., Salmon, S., Davila, I. G., Stewart-Tufescu, A., Fortier, J., Struck, S., Asmundson, G. J. G., Sareen, J., & MacMillan, H. L. (2020b). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), peer victimization, and substance use among adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 106, 104504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104504

Anda, R. F., Croft, J. B., Felitti, V. J., Nordenberg, D., Giles, W. H., Williamson, D. F., & Giovino, G. A. (1999). Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA, 282(17), 1652–1658. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.17.1652

Bava, S., & Tapert, S. F. (2010). Adolescent brain development and the risk for alcohol and other drug problems. Neuropsychology Review, 20(4), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-010-9146-6

Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. Harcourt Brace & Co..

Boyle, M. H., Georgiades, K., Duncan, L., Comeau, J., Wang, L., & 2014 Ontario Child Health Study Team. (2019). The 2014 Ontario Child Health Study-Methodology. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(4), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719833675

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2014). National crime victimization survey: Technical documentation. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ncvstd13.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan 2016

Carroll Chapman, S. L., & Wu, L.-T. (2013). Substance use among adolescent mothers: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(5), 806–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.02.004

Cheung, K., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., Fortier, J., Sareen, J., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M. H., & Afifi, T. O. (2017). Relationship and community factors related to better mental health following child maltreatment among adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.026

Cheung, K., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., Fortier, J., Sareen, J., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M. H., & Afifi, T. O. (2018). Individual-level factors related to better mental health outcomes following child maltreatment among adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79, 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.02.007

Dembo, R., Belenko, S., Childs, K., & Wareham, J. (2009). Drug use and sexually transmitted diseases among female and male arrested youths. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9183-2

Eskritt, M., Doucette, J., & Robitaille, L. (2014). Does future-oriented thinking predict adolescent decision making? Journal of Genetic Psychology, 175(1-2), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2013.875886

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

Haggstrom Westberg, K., Wilhsson, M., Svedberg, P., Nygren, J. M., Morgan, A., & Nyholm, M. (2019). Optimism as a candidate health asset: Exploring its links with adolescent quality of life in Sweden. Child Development, 90(3), 970–984. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12958

Hammond, C. J., Chaney, A., Hendrickson, B., & Sharma, P. (2020). Cannabis use among U.S. adolescents in the era of marijuana legalization: A review of changing use patterns, comorbidity, and health correlates. International Review of Psychiatry, 32(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1713056

Hengartner, M. P., Angst, J., Ajdacic-Gross, V., & Rossler, W. (2020). Cannabis use during adolescence and the occurrence of depression, suicidality and anxiety disorder across adulthood: Findings from a longitudinal cohort study over 30 years. Journal of Affective Disorders, 272, 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.126

Herrman, H., Stewart, D. E., Diaz-Granados, N., Berger, E. L., Jackson, B., & Yuen, T. (2011). What is resilience? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(5), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371105600504

Ibrahim, M. H., Somers, J. A., Luecken, L. J., Fabricius, W. V., & Cookston, J. T. (2017). Father-adolescent engagement in shared activities: Effects on cortisol stress response in young adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(4), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000259

Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Miech, R. A., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2017). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2016: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-ov. Accessed 4 Apr 2019

Lardier, D. T., Opara, I., Reid, R. J., & Garcia-Reid, P. (2020). The role of empowerment-based protective factors on substance use among youth of color. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37(3), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00659-3

Lee, J. Y., Kim, W., Brook, J. S., Finch, S. J., & Brook, D. W. (2020). Adolescent risk and protective factors predicting triple trajectories of substance use from adolescence into adulthood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01629-9

Liang, W., & Chikritzhs, T. (2015). Age at first use of alcohol predicts the risk of heavy alcohol use in early adulthood: A longitudinal study in the United States. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(2), 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.07.001

Masten, A. S. (2013). Risk and resilience in development. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of Developmental Psychology (pp. 579–607). Oxford University Press.

Mathijssen, J. J. P., Janssen, M. M., van Bon-Martens, M. J. H., van Oers, H. A. M., de Boer, E., & Garretsen, H. F. L. (2014). Alcohol segment-specific associations between the quality of the parent-child relationship and adolescent alcohol use. BMC Public Health, 14(872). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-872

Moore, G. F., Cox, R., Evans, R. E., Hallingberg, B., Hawkins, J., Littlecott, H. J., Long, S. J., & Murphy, S. (2018). School, peer and family relationships and adolescent substance use, subjective wellbeing and mental health symptoms in Wales: A cross sectional study. Child Indicators Research, 11(6), 1951–1965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9524-1

Palmer, C. A., Oosterhoff, B., Bower, J. L., Kaplow, J. B., & Alfano, C. A. (2018). Associations among adolescent sleep problems, emotion regulation, and affective disorders: Findings from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 96, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.015

Partners in Planning for Healthy Living. (2013). Manitoba Youth Health Survey 2012/2013 User Guide.

Pittenger, S. L., Moore, K. E., Dworkin, E. R., Crusto, C. A., & Connell, C. M. (2018). Risk and protective factors for alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use among child welfare-involved youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 95, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.09.037

Schulte, M. T., & Hser, Y.-I. (2013). Substance use and associated health conditions throughout the lifespan. Public Health Reviews, 35(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391702

Statistics Canada. (2017, November 29, 2017). Winnipeg, CY, Manitoba and Canada (table). Retrieved May 7, 2019 from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Stewart-Tufescu, A., Salmon, S., Taillieu, T., Fortier, J., & Afifi, T. O. (2021). Victimization experiences and mental health outcomes among grades 7 to 12 students in Manitoba, Canada. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 3, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00056-0

Turner, S., Taillieu, T., Fortier, J., Salmon, S., Cheung, K., & Afifi, T. O. (2018). Bullying victimization and illicit drug use among students in Grades 7 to 12 in Manitoba, Canada: A cross-sectional analysis. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 109(2), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-018-0030-0

Unger, J. B., Sussman, S., Begay, C., Moerner, L., & Soto, C. (2020). Spirituality, ethnic identity, and substance use among American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents in California. Substance Use & Misuse, 55(7), 1194–1198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1720248

Volkow, N. D., Baler, R. D., Compton, W. M., & Weiss, S. R. (2014). Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(23), 2219–2227. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1402309

Wald, J., Taylor, S., Asmundson, G. J. G., Jang, K. L., Stapleton, J., & McCreary, D. (2006). Literature review of concepts: Psychological resiliency, Final Report W7711-057959/A.

Walsh, C. A., MacMillan, H. L., Trocme, N., Jamieson, E., & Boyle, M. H. (2008). Measurement of victimization in adolescence: Development and validation of the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(11), 1037–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.05.003

Zuckermann, A. M. E., Williams, G. C., Battista, K., Jiang, Y., de Groh, M., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of youth poly-substance use in the COMPASS study. Addictive Behaviors, 107, 106400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106400

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Manitoba.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Afifi, T.O., Taillieu, T., Salmon, S. et al. Protective Factors for Decreasing Nicotine, Alcohol, and Cannabis Use Among Adolescents with a History of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Int J Ment Health Addiction 21, 2255–2273 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00720-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00720-x