Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in multiple physical and psychological stressors, which require quantification and establishment of association with other psychological process variables. The Coronavirus Stress Measure (CSM) is a validated instrument with acceptable validity and reliability. This study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the CSM in a Malaysian population. University participants were recruited via convenience sampling using snowball methods. The reliability and validity of the Malay CSM (CSM-M) were rigorously evaluated, utilising both confirmatory factor analysis and Rasch analysis, in relation to sociodemographic variables and response to the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales of the Malay validation of the DASS-21, and also perceived stress (measured by the PSS) and psychological flexibility (AAQ-II). The sample comprised of 247 Malaysian participants. The McDonald’s omega value for the Malay CSM was 0.935 indicating very good internal reliability. The CSM was significantly correlated with stress, anxiety, depression, perceived stress, and psychological flexibility. The Malay CSM properties were examined also with Rasch analysis, with satisfactory outcomes. There was positive correlated error between items 1 and 3, as well as negative correlated error between items 1 and 4. Hence, item 1 was excluded, leaving with 4 items. Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated good data-model fit, and model fit statistics confirmed that Malay CSM showed a single-factor model. The Malay CSM hence demonstrates good validity and reliability, with both classical and modern psychometric methods demonstrating robust outcomes. It is therefore crucial in operational and research settings in establishing the true extent of stress levels as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which started in late December 2019 in Wuhan, China, has gradually spread across the world (Rothan & Byrareddy, 2020). With second and third waves assaulting multiple nations, many have moved towards endemicity rather than flattening of curves (Hunter, 2020). Unprecedented levels of stress have emerged globally (Horesh & Brown, 2020) which can be conceptualised as having both physical and psychological origins. Physically, acute infections and chronic sequelae can drive up human cortisol levels; psychologically, the uncertainty in terms of education, employment, social engagement, relationships, and travel signified that COVID-19 has left adverse consequences that are further reaching than merely pandemic-related fear.

Malaysia has suffered unprecedented levels of stress during the pandemic, as it has grappled with a third wave of COVID-19 that as yet remains unabated after an initial period of quiescence from June to September 2020 (Pang et al., 2021b). Two successive national lockdowns were imposed for a total of 3 months, with the second one still in progress. This led to high levels of stress in the Malaysian population due to the loss of economic and education opportunities. The level of COVID-19-related stress in Malaysia was especially jarring, as the majority of Malaysia’s neighbouring countries such as Singapore, Thailand, and Brunei were able to successfully control the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, evidence has shown that COVID-related stress reactions worsen symptoms in clinical and non-clinical individuals, especially in individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions (Asmundson et al., 2020; Khosravani et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2020a). Anxiety and depressive symptoms markedly rose (Huang & Zhao, 2020; Jungmann & Witthöft, 2020; Tull et al., 2020), as well as the prevalence of sleep disturbances (Deng et al., 2020; Gualano et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Rajkumar, 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). Additionally, the incidence of suicide increased, which could be directly attributed to COVID-19 or indirectly to its negative consequences, such as socioeconomic pressure (Caballero-Domínguez et al., 2020; Dsouza et al., 2020; Sher, 2020; Thakur & Jain, 2020; Tomisawa & Katanuma, 2020). Thus, it is crucial that we examine stress specific to COVID-19 in a Malay-speaking culture, as much of the extant research has been performed outside Asian cultures. At the same time, the lack of a Malay validated version prevents collection of nationwide data that can be compared reliably across geographical and cultural boundaries. Non-validated scales suffer from multiple limitations including limited generalisability, lack of conceptual consistency, and poor psychometric properties (N. Pang, et al., 2020a, b, c). Hence, it is crucial that a Malay language validation is performed using watertight statistical measures. Rasch analysis has begun to find favour over classical test theory (CTT), as the latter focuses more on complete sets of raw scores and statistical interpretation henceforth, whereas Rasch analysis attempts to obtain data that fits the model. Therefore, Rasch analysis also has the advantage of being more robust against missing data. Moreover, Rasch models are able to demonstrate the association between the response given to the item and underlying latent variables.

To properly comprehend the psychological distress stemming from COVID-19, a few psychological instruments have been developed, such as the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (Ahorsu et al., 2020), the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (S. A. Lee, 2020), and the COVID Stress Scales (Taylor et al., 2020b). Another useful instrument that can contribute to the growing list of psychological assessments in these COVID times is the Coronavirus Stress Measure (CSM) (Arslan et al., 2020). The CSM is a five-item instrument adapted from the Perceived Stress Scale that aims to measure the very specific stresses resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic (Arslan et al., 2020). Its psychometric properties, construct, and convergent validity have been established. Additionally, psychological inflexibility has been implicated in psychological distress in numerous studies before (Crasta et al., 2020; Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, 2020; Fernández et al., 2020; Landi et al., 2020; McCracken et al., 2021). Psychological inflexibility has been also demonstrated to significantly mediate the negative impacts of coronavirus stress on adults’ optimism and pessimism (Arslan et al., 2020).

Accordingly, this study aims to validate the established CSM into the Malay language, hence joining the stable of existing validated COVID-related instruments into the Malay language, namely the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (Kassim et al., 2020; Pang et al., 2020b). This will allow accurate measurements of the specific stress towards COVID-19 to be captured amongst individuals in the Malay diaspora. This is crucial as Malay is within the top ten languages with the highest number of speakers in the world, covering Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Indonesia, and parts of Thailand, with an estimation of 220 million speakers (J. W. Wright, 2007). Moreover, there are increasing mental health issues, with over 37,000 phone calls to psychological hotlines made up until November 2020; such numbers are expected to increase as the second wave goes unabated (Lim, 2020). Therefore, having a validated Malay language CSM will allow us to measure associations between coronavirus-related stress and other constructs, including but not limited to coping styles, psychological process variables (Pang et al., 2020c), other psychopathologies (Pang et al., 2021a), and other relevant factors that can impact on stress. This study thus hypothesises that the Malay CSM is a reliable instrument to quantitatively measure COVID-19-related stress and is distinctly different from generic stress measurement instruments such as the Perceived Stress Scale.

Methodology

Participants

Ethical approval was obtained from the Universiti Malaysia Sabah Medical Research Ethics Committee. This was performed as a cross-sectional study in a sample of university students. Due to global social distancing restrictions in light of COVID-19, all data were collected through Google Forms. The inclusion criteria were all university students and staff in a comprehensive public university in Malaysia who consented and understand the questionnaire fully, with the exclusion criteria being all individuals with acute medical and psychiatric illness or those who had issues with consent or comprehension. Snowball sampling methods were employed amongst students and staff of five faculties or departments. All participants filled in a basic sociodemographic questionnaire and the following validated research instruments to assess convergent validity.

Two hundred and forty-seven participants voluntarily participated in this study. None of the participants had a previous or current history of COVID infection. The study was done between April 2020 and early June 2020.

Measures

Coronavirus Stress Measure (English and Malay Version)

The English version of the Coronavirus Stress Measure was administered together with the Malay version. The CSM is a valid and reliable measurement tool assessing COVID-19-related stress, demonstrating satisfactory internal consistency reliability estimate with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 (Arslan et al., 2020). Standard World Health Organisation translation guidelines were employed in producing the translated version. Two separate individuals were employed to forward translate it: one as a content expert and another as a language expert. Subsequently, one more content expert and another one language expert, blind to the identities of the original two experts and blind to the original questionnaire, back translated the newly prepared Malay version into English. The four translators then compared all four versions for inconsistencies, unusual turns of phrase, jargon, or technical terms. The final result of this harmonisation process was then pilot tested on 20 individuals representing the general population, who then gave feedback regarding the translation.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) (Malay Version)

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) is an instrument to assess experiential avoidance and psychological inflexibility (Bond et al., 2011). Experiential avoidance can be defined as an attempt to avoid or neglect unpleasant thought, feelings, bitter memories, and uncomfortable physical sensations, consequently lead to an action that is against one’s values and causing long-term harm. Psychological inflexibility refers to rigid psychological reaction against one’s value in order to avoid distress, uncomfortable feeling and thought, and thus ignoring the present moment. The AAQ-II consists of 7 items (e.g. “I’m afraid of my feeling”, “Emotions cause problems in my life”) scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true). A higher score on the AAQ-II indicates a greater level of experiential avoidance. It has been demonstrated to be a stable unidimensional measure across different populations and times. The unidimensional factor indicates that AAQ-II is a specific measurement tool for experiential avoidance. The AAQ-II Malay version has an established content validity index, acceptable internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.91, excellent parallel reliability, and adequate concurrent validity (Shari et al., 2019). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results demonstrated that the AAQ-II Malay version has a unidimensional factor structure. Sensitivity and specificity analyses of the AAQ-II Malay version indicated that cancer patients who scored more than 17.5 had significant psychological inflexibility.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) (Malay Version)

The DASS-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) is a self-report scale designed to measure the severity of emotional distress (depression and anxiety, and stress). It contains 21 items measuring three different domains: depression (e.g. “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all”), anxiety (e.g. “I was aware of dryness of my mouth”), and stress (e.g. “I found it hard to wind down”). Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all over the last week) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time over the past week). Higher scores in each domain indicate greater severity of emotional distress in that domain. In the present study, the Malay version of the DASS-21 (Musa & Fadzil, 2007) was used to measure emotional distress in caregivers. The Malay validation demonstrated acceptable Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.84, 0.74, and 0.79, respectively, for depression, anxiety, and stress. In addition, it had good factor loading values for most items (0.39 to 0.73).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Malay Version)

One of the most widely disseminated methods of assessing stress is the Perceived Stress Scale, which measures feelings and thoughts in the past one month that are associated with life events and events out of control. The PSS-10 has 10 items (e.g. “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed?”) on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = fairly often, 4 = very often). Four positively stated items (items 4, 5, 7, and 8) (e.g. “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were on top of things?”) are reversely scored (0 = very often, 1 = fairy often, 2 = sometimes, 3 = almost never, 4 = never). The sum of the 10 items represents the total score, with higher scores representing higher levels of perceived stress (Al-Dubaai et al., 2012). Its internal reliability is statistically reasonable, with a Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70 in 12 separate studies, whereas the test–retest reliability of the PSS-10 > 0.70 in 4 studies (E. H. Lee, 2012). The Malay version of PSS has also shown good psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 and 0.70 for its 2 factors, respectively, as well as an ICC of 0.82.

Data Analysis

Two psychometric methods were used to check the validity and reliability of the Malay version of the Coronavirus Stress Measure, namely classical test theory (CTT) (Novick, 1966) and Rasch measurement theory (RMT) (Hobart & Cano, 2009).

The validity and reliability tests were divided into two levels, namely scale level (the analyses were done at scale level) and item level (the analyses were done at item level). Firstly, for the scale level, CCT employed internal consistency measures using McDonald’s omega, test–retest reliability using Pearson correlation tests (Malay version versus English version), average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability, and standard error of measurement. To evaluate the concurrent validity of the CSM, the correlations of the CSM with the DASS-21, the AAQ-II, and the PSS were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation. Meanwhile, the RMT methods used were item and person separation reliability and item and person separation index.

On the other hand, for the item level, the CTT employed item-item correlation and item-total correlation, while the RMT used infit and outfit mean square (MnSq) and differential item functioning (DIF) to test the measurement invariance across gender. The CTT was run using IBM SPSS 24.0, while the RMT was run using jMetrik 4.1.1. The McDonald’s omega was calculated using JASP. Subsequently, CFA was performed to examine the factor structure and was run using IBM SPSS Amos.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

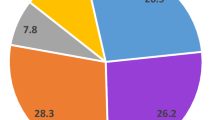

Descriptive statistics suggested that the majority of participants were females, of Bumiputera Sabah ethnicity, who are mostly Muslim and single, and with a household size of more than 5 (Table 1). Most of the households did not contain any individuals of extremes of age (less than 6 or more than 60) and were generally healthy. As shown by Table 2, the mean for all items ranged from 2.06 to 2.29, and the skewness and kurtosis for all items were well within the accepted limits of ± 2 suggesting they fell within the bounds of statistical normality.

Reliability and Validity

At the Scale Level

All the psychometric measures as demonstrated in Table 3 confirmed the validity and reliability of the Malay version of CSM. Assessments of the internal consistency of the Malay CSM using McDonald’s omega confirmed the items co-varied relative to the sum score of the scale. Significant correlations with other stress measurements (i.e. DASS, AAQ-II scale, and PSS scale) also proved the concurrent validity of the Malay CSM. A partial correlation test also showed that the Malay version of CSM was still significantly correlated with the depression scale (correlation coefficient = 0.381, df = 244, p-value < 0.001) and anxiety scale (correlation coefficient = 0.401, df = 244, p-value < 0.001) even after controlling the stress measured via the PSS. Similarly, Rasch analysis demonstrated satisfactory results, with the separation reliability and separation index both above the suggested cut-off. A separation index of more than 2 suggest that the Malay version of CSM was able to at least separate respondents into two categories—lower and higher stress levels.

The results of three multivariable models as shown in Table 4 confirmed that the Malay CSM had significant positive effects on all the dependent variables, namely depression, anxiety, and also stress. The VIF values also indicated that there was no issue of multicollinearity among the independent variables (i.e. the Malay CSM, AAQ-II, PSS) since all values were below 5. Therefore, this suggested that the Malay CSM was able to independently predict depression, anxiety, and stress beyond generic stress as measured by the PSS.

At the Item Level

The results of the Pearson correlation coefficient showed that all the inter-item correlation coefficients were higher than 0.3 (see Table 5). This implies that the instrument has an acceptable validity (Cohen, 1992). Furthermore, there was no corrected item-total correlation coefficient with a value of less than 0.5 (see Table 6). In an empirical approach and as a rule of thumb, if the score of the item-to-total correlations is more than 0.50 and the inter-item correlations exceed 0.30, the construct validity is satisfied (Robinson et al., 1991).

Additionally, at the item level, all the factor loadings were higher than 0.3 which suggest that the items were important (Pituch & Stevens, 2016) (see Table 7). All the communalities were also closer to 1 suggesting that extracted factor explained more of the variance of an individual item. Rasch analysis was also satisfactory where infit MnSq values were between 0.83 and 1.31, whereas outfit MnSq values were between 0.82 and 1.33. These item fit statistics showed that each item meets the unidimensional requirement of a Rasch model as all the values were within 0.5–1.5 range (B. D. Wright & Linacre, 1994). The most difficult item was Item 1 (i.e. the highest value), and the easiest item was Item 2 (i.e. the lowest value). There was also no substantial DIF found across gender since all the DIF contrast values were less than 0.5 (Shih & Wang, 2009) suggesting that the scale was not sensitive to gender.

A trace line (also known as the item characteristic curve, ICC) is a graphic representation of the probability of which category or option will be answered by a person with a certain level of latent trait. As shown in Fig. 1, the trace lines indicated that the item anchors were properly functioning as ordered for all items.

The item information curves plotted (see Fig. 2) showed that three of the items (i.e. item 1, item 3, and item 5) had a bimodal information that generally peaked between θ = − 2.5 and 0 and between 2.5 and 5.0. Item 1 had slightly lower information across the latent trait continuum compared to the other items, suggesting that item 1 could be dropped without decreasing the scale reliability, given that the Malay CSM is unidimensional. Aggregating the item information curves produced a test information curve that demonstrates a similar pattern, suggesting that the Malay CSM was appropriate.

One Factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the CSM Malay Version

The factor structure of the 5-question CSM Malay version was also examined using confirmatory factor analysis, showing good data-model fit statistics (χ2 (3, N = 247) = 7.282, p = 0.063; CFI = 0.996, TLI = 0.987, NFI = 0.993, IFI = 0.996, SRMR = 0.0013, GFI = 0.989, and RMSEA = 0.076). However, it was noted there was positive correlated error between items 1 and 3, as well as negative correlated error between items 1 and 4 (See Fig. 3). Hence, item 1 was excluded, leaving the scale with 4 items. Subsequent confirmatory factor analysis on the 4-item CSM Malay version showed improved model fit, with absence of correlated error (χ2 (3, N = 247) = 3.398, p = 0.183; CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.995, NFI = 0.996, IFI = 0.998, SRMR = 0.0009, GFI = 0.993, and RMSEA = 0.0053) (see Fig. 4). CFI, TLI, NFI, IFI, and GFI values of > 0.90 are generally considered as good fit (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Bollen, 1989; Sharma et al., 2005; Tanaka & Huba, 1985), while the cut-off value for SRMR good fit is < 0.08 (Hooper et al., 2008). On the other hand, RMSEA cut-off value of 0.05 has been suggested to indicate good fit, while cut-off value of 0.08 indicates acceptable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). The model fit statistics confirmed that the Malay version of CSM fulfilled a single-factor model.

Discussion

This study aimed to validate the existing CSM into the Malay language as a tool to assess psychological stress specifically due to COVID-19. The results suggest that the Malay CSM has adequate psychometric properties, as it has high internal consistency with a McDonald’s omega value in excess of 0.9. Moreover, it has satisfactory characteristics based on Rasch analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis also demonstrates good data-model fit statistics. Item 1 of the CSM Malay version was excluded in view of correlated errors between items 1 and 3, as well as items 1 and 4. This could be attributed to language inconsistency, as the word “upset” in item 1 could be interpreted differently in many ways in the Malay language, such as “not happy”, “disappointed”, “sad”, and “angry”. The inconsistency of language could influence the way participants answer the item and may then cause covariation beyond the latent variable (Lewis & Mayer, 1987; Tourangeau et al., 2003; Uhan & Fink, 2013). Regardless, a 4-item CSM Malay version, with its robust psychometric properties, good reliability, and validity, is a vital tool to add to the armamentarium of scales that can assess psychological factors related to COVID-19, alongside the recently validated Fear of COVID-19 Scale (Pang et al., 2020b).

Coronavirus has no doubt resulted in high levels of stress, which might not be adequately captured by the existing Perceived Stress Scale. However, the stress does not merely stem from the sequelae of contracting the physical infection. There is also a component of psychological fear stemming from the myriad sequelae. From stigma (Shoesmith & Pang, 2016), to fear of being quarantined (Kassim et al., 2021), to fear of losing one’s opportunities for employment and education (Hafiz Mukhsam et al., 2020; Salvaraji et al., n.d.), COVID-19 has potentially changed how an entire generation think, operate, and live their normal lives in a “new normal” (Kassim et al., 2020; Sahu, 2020; Serafini et al., 2020; Thakur & Jain, 2020). This would render the CSM important as it would measure a somewhat different construct compared to the two existing stress measures in the market—the DASS (stress subscale) and the Perceived Stress Scale. Both have adequate psychometric properties but suffer from the limitation of not being current in capturing the unique fears and stressors that are related to COVID-19.

This finding is valuable in view of the limited extant literature on how Malaysian communities respond to COVID-19-related stress. An IPSOS survey done in early 2021 across 28 countries suggested Malaysians are among the most stressed and scored much higher compared to the global average in terms of stress perception (Muhamad et al., 2021). A few subsequent studies in the Malaysian population suggested that level of stress as well as anxiety have been peaking over the course of the pandemic (Deng et al., 2020; Faez et al., 2020; Kassim et al., 2021; Perveen et al., 2020; Shanmugam et al., 2020; Sundarasen et al., 2020; Wan Mohd Yunus et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Woon et al., 2020). Hence, future studies would benefit from the findings of the current study, as we can examine whether there are other more intricate relationships between COVID-19 stress and other psychological constructs, for instance, fear of COVID-19, as have been demonstrated in other similar healthcare worker populations in Malaysia (Pang et al., 2021a). As the scale to measure fear has been validated in both Malaysian and Indonesian populations (Kassim et al., 2020; Pang et al., 2020b), the CSM validation into the Malay language can be easily adapted to the Indonesian language and undergo further validation procedures, in order to assess if fear and stress are related and also to further explore what factors contribute partially to both constructs’ emergence and continuation.

There are certain limitations with the existing validation. Firstly, this sample largely consists of undergraduate university students. However, due to the unprecedented nature of the lockdown, university students were easiest to employ as it was virtually impossible to perform a traditional face to face recruitment. Subsequently, this limits the CSM-Malay’s applicability in future studies that may wish to employ an older adult population, and it is crucial that this study be replicated when lockdown measures ease in a population that bears a closer resemblance to the general adult population. Further, another limitation is that the CSM will be by definition limited in its scope, as stress is multifaceted and can be target-specific; this is unlikely to be captured using a simplistic four-item measure. Hence, the CSM would be more useful in time-poor scenarios or situations where lower levels of education may hamper individuals in answering long questionnaires. In ideal research contexts, it would of course be preferable that more comprehensive questionnaires be employed that better encapsulate the multifaceted nature of stress.

In conclusion, the CSM Malay version represents a pioneering validation of a modified Perceived Stress Scale that is more relevant in capturing the stresses evident from COVID-19. It has been demonstrated to have concurrent validity with multiple instruments that measure similar constructs. Further research is needed to establish whether it is also relevant in clinical as well as non-clinical settings, in order to widen its use.

References

Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C. Y., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8

Al-Dubaai, S. A. R., Alshagga, M. A., Rampal, K. G., & Sulaimaan, N. A. (2012). Factor structure and reliability of the Malay version of the perceived stress scale among Malaysian medical students. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 19, 43–9.

Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., Tanhan, A., Buluş, M., & Allen, K. A. (2020). Coronavirus stress, optimism-pessimism, psychological inflexibility, and psychological health: Psychometric properties of the coronavirus stress measure. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00337-6

Asmundson, G. J. G., Paluszek, M. M., Landry, C. A., Rachor, G. S., McKay, D., & Taylor, S. (2020). Do pre-existing anxiety-related and mood disorders differentially impact COVID-19 stress responses and coping? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102271

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., … Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire--II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Testing structural equation models 154:136–62.

Caballero-Domínguez, C. C., Jiménez-Villamizar, M. P., & Campo-Arias, A. (2020). Suicide risk during the lockdown due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Colombia. Death Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1784312

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

Crasta, D., Daks, J. S., & Rogge, R. D. (2020). Modeling suicide risk among parents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Psychological inflexibility exacerbates the impact of COVID-19 stressors on interpersonal risk factors for suicide. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.003

Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

Deng, J., Zhou, F., Hou, W., Silver, Z., Wong, C. Y., Chang, O., … Zuo, Q. K. (2020). The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID‐19 patients: a meta‐analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14506

Dsouza, D. D., Quadros, S., Hyderabadwala, Z. J., & Mamun, M. A. (2020). Aggregated COVID-19 suicide incidences in India: Fear of COVID-19 infection is the prominent causative factor. Psychiatry Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113145

Faez, M., Hadi, J., Abdalqader, M., Assem, H., Omar Ads, H., & Faisal Ghazi, H. (2020). Impact of lockdown due to Covid-19 on mental health among students in private university at Selangor. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine, 7(11), 508–517.

Fernández, R. S., Crivelli, L., Guimet, N. M., Allegri, R. F., & Pedreira, M. E. (2020). Psychological distress associated with COVID-19 quarantine: Latent profile analysis, outcome prediction and mediation analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.133

Gualano, M. R., Lo Moro, G., Voglino, G., Bert, F., & Siliquini, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134779

Hafiz Mukhsam, M., Saffree Jeffree, M., Tze Ping Pang, N., Sharizman Syed Abdul Rahim, S., Omar, A., Syafiq Abdullah, M., … Putri Zainudin, S. (2020). A university-wide preparedness effort in the alert phase of COVID-19 incorporating community mental health and task-shifting strategies: Experience from a Bornean Institute of Higher Learning. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(3), 1201–1203. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0458

Hobart, J., & Cano, S. (2009). Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: the role of new psychometric methods. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta13120.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.21427/D79B73

Horesh, D., & Brown, A. D. (2020). Covid-19 response: Traumatic stress in the age of Covid-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1037/TRA0000592

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

Hunter, P. (2020). The spread of the COVID ‐19 coronavirus. EMBO Reports. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050334

Jiang, Z., Zhu, P., Wang, L., Hu, Y., Pang, M., Tang, X., & Ma, S. (2020). Psychological distress and sleep quality of COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, a lockdown city as the epicenter of COVID-19. Journal of Psychiatric Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.034

Jungmann, S. M., & Witthöft, M. (2020). Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID-19 pandemic: Which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 73, 102239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102239

Kassim, M. A. M., Ayu, F., Kamu, A., Pang, N. T. P., Ho, C. M., Algristian, H., … Omar, A. (2020). Indonesian version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Validity and reliability. Borneo Epidemiology Journal, 1(2), 124–135.

Kassim, M. A. M., Pang, N. T. P., Mohamed, N. H., Kamu, A., Ho, C. M., Ayu, F., … Jeffree, M. S. (2021). Relationship between Fear of COVID-19, psychopathology and sociodemographic variables in Malaysian Population. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–8.

Khosravani, V., Asmundson, G. J. G., Taylor, S., Sharifi Bastan, F., & Samimi Ardestani, S. M. (2021). The Persian COVID stress scales (Persian-CSS) and COVID-19-related stress reactions in patients with obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 28, 100615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2020.100615

Landi, G., Pakenham, K. I., Boccolini, G., Grandi, S., & Tossani, E. (2020). Health anxiety and mental health outcome during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: The mediating and moderating roles of psychological flexibility. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2195. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02195

Lee, E. H. (2012). Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004

Lee, S. A. (2020). Coronavirus anxiety scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Studies, 44(7), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481

Lewis, A. B., & Mayer, R. E. (1987). Students’ miscomprehension of relational statements in arithmetic word problems. Journal of Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.79.4.363

Lim, I. (2020). The Covid-19 mental toll on Malaysia: Over 37,000 calls to help hotlines.

Lovibond, P. F., Lovibond S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour research and therapy 33(3):335-43

McCracken, L. M., Badinlou, F., Buhrman, M., & Brocki, K. C. (2021). The role of psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19: Associations with depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 19, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.11.003

Muhamad, A. B., Pang, N. T., Salvaraji, L., Rahim, S. S., Jeffree, M. S., & Omar, A. (2021). Retrospective Analysis of Psychological Factors in COVID-19 Outbreak Among Isolated and Quarantined Agricultural Students in a Borneo University. Frontiers in Psychiatry., 12, 483.

Musa, R., Fadzil, M. A., & Zain, Z. A. (2007). Translation, validation and psychometric properties of Bahasa Malaysia version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS). ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry, 8(2), 82–9.

Pang, N., Lee, G., Tseu, M., Joss, J. I., Honey, H. A., Shoesmith, W., … Lasimbang, H. (2020). Validation of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT)--Dusun version in alcohol users in Sabahan Borneo. Archives of Psychiatry Research: An International Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 56(2), 129–142.

Pang, N. T. P., Imon, G. N., Johoniki, E., Kassim, M. A. M., Omar, A., Rahim, S. S. S. A., … Ng, J. R. (2021). Fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 stress and association with sociodemographic and psychological process factors in cases under surveillance in a frontline worker population in Borneo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, Vol. 18, Page 7210, 18(13), 7210. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH18137210

Pang, N. T. P., Kamu, A., Hambali, N. L., Ho, C. M., Mohd Kassim, M. A., Mohamed, N. H., … Jeffree, M. S. (2020). Malay version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Validity and reliability. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00355-4

Pang, N. T. P., Kamu, A., Mohd Kassim, M. A., & Chong Mun, H. (2021). Analyses of the effectiveness of Movement Control Order (MCO) in reducing the COVID-19 confirmed cases in Malaysia. Journal of Health and Translational Medicine, (1), 16–27. https://jummec.um.edu.my/article/view/24068. Accessed 11 July 2021

Pang, N. T. P., Masiran, R., Tan, K.-A., & Kassim, A. (2020). Psychological mindedness as a mediator in the relationship between dysfunctional coping styles and depressive symptoms in caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 56, 649–656.

Perveen, A., Motevalli, S., Hamzah, H., & Mutiu, S. (2020). The comparison of depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies among Malaysian male and female during COVID-19 movement control period how children and young people can deal with difficult life situations View project. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i7/7451

Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. (2016). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences: Analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS (6th ed.). Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Rajkumar, R. P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

Robinson, J. P., Shaver, P. R., & Wrightsman, L. S. (1991). Criteria for scale selection and evaluation. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-590241-0.50005-8

Rothan, H. A., & Byrareddy, S. N. (2020). The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Journal of Autoimmunity, 109, 102433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433

Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

Salvaraji, L., Rahim, S. S., Jeffree, M. S., Omar, A., Pang, N. T., Ahmedy, F., et al. (2020). The importance of high index of suspicion and immediate containment of suspected COVID-19 cases in institute of higher education Sabah, Malaysia Borneo. Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine., 20(2), 74–83.

Serafini, G., Parmigiani, B., Amerio, A., Aguglia, A., Sher, L., & Amore, M. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201

Shanmugam, H., Juhari, J. A., Nair, P., Chow, S. K., & Ng, C. G. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in Malaysia : A single thread of hope. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry 29(1), 78–84.

Shari, N. I., Zainal, N. Z., Guan, N. C., Sabki, Z. A., & Yahaya, N. A. (2019). Psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire (AAQ II) Malay version in cancer patients. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0212788. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212788

Sharma, S., Mukherjee, S., Kumar, A., & Dillon, W. R. (2005). A simulation study to investigate the use of cutoff values for assessing model fit in covariance structure models. Journal of Business Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.10.007

Sher, L. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202

Shih, C. L., & Wang, W. C. (2009). Differential item functioning detection using the multiple indicators, multiple causes method with a pure short anchor. Applied Psychological Measurement, 33(3), 184–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621608321758

Shoesmith, W. D., & Pang, N. T. P. (2016). The interpretation of depressive symptoms in urban and rural areas in Sabah Malaysia. ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry, 17(1), 42–53.

Novick, M. R. (1966 Feb 1). The axioms and principal results of classical test theory. Journal of mathematical psychology., 3(1), 1–8.

Sundarasen, S., Chinna, K., Kamaludin, K., Nurunnabi, M., Baloch, G. M., Khoshaim, H. B., … Sukayt, A. (2020). Psychological impact of covid-19 and lockdown among university students in Malaysia: Implications and policy recommendations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176206

Tanaka, J. S., & Huba, G. J. (1985). A fit index for covariance structure models under arbitrary GLS estimation. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1985.tb00834.x

Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Fergus, T. A., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2020). COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and Anxiety, 37(8), 706–714. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23071

Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Fergus, T. A., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2020b). Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 72, 102232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232

Thakur, V., & Jain, A. (2020). COVID 2019-suicides: A global psychological pandemic. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.062

Tomisawa, A., Katanuma, M. (2021) Suicide spike in Japan shows mental health toll of COVID-19. The Japan Times. 2020. Hafner-Fink M, Uhan S. Life and attitudes of Slovenians during the COVID-19 pandemic: The problem of trust. International Journal of Sociology 51(1), 76-85.

Tourangeau, R., Singer, E., & Presser, S. (2003). Context effects in attitude surveys: Effects on remote items and impact on predictive validity. Sociological Methods and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124103251950

Tull, M. T., Barbano, A. C., Scamaldo, K. M., Richmond, J. R., Edmonds, K. A., Rose, J. P., & Gratz, K. L. (2020). The prospective influence of COVID-19 affective risk assessments and intolerance of uncertainty on later dimensions of health anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 75, 102290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102290

Uhan, S., & Fink, M. H. (2013). Context effects in social surveys: Between instrument and respondent. Teorija in Praksa.

Wan MohdYunus, W. M. A., Badri, S. K. Z., Panatik, S. A., & Mukhtar, F. (2021). The unprecedented movement control order (Lockdown) and factors associated with the negative emotional symptoms, happiness, and work-life balance of Malaysian university students during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 566221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.566221

Wang, C., Tee, M., Roy, A. E., Fardin, M. A., Srichokchatchawan, W., Habib, H. A., … Kuruchittham, V. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: A study of seven middle-income countries in Asia. PLOS ONE, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246824

Woon, L.S.-C., Sidi, H., Nik Jaafar, N. R., Abdullah, L. B., & M. F. I. . (2020). Mental health status of university healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A post–movement lockdown assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249155

Wright, B. D., & Linacre, J. M. (1994). Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 8, 370–371.

Wright, J. W. (2007). The New York Times Almanac : The Almanac of Record. Penguin Putnam Inc.

Zhao, Q., Hu, C., Feng, R., & Yang, Y. (2020). Investigation of the mental health of patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chinese Journal of Neurology 53(6).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kassim, M.A.M., Pang, N.T.P., Kamu, A. et al. Psychometric Properties of the Coronavirus Stress Measure with Malaysian Young Adults: Association with Psychological Inflexibility and Psychological Distress. Int J Ment Health Addiction 21, 819–835 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00622-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00622-y