Abstract

Internet gaming disorder (IGD) is a rapidly expanding psychopathological manifestation necessitating further research and clinical attention. Although recent research has investigated relationships between user-avatar and excessive gaming, little is known about the interplay between IGD and avatar self-presence and its dimensions (i.e., the physical, emotional, and identity bond developed between the user and the in-game character). The aim of the present pilot study was twofold: (i) to investigate the associations between physical, emotional, and identity aspects of self-presence associate and IGD severity, and (ii) to assess IGD variations longitudinally in relation to the three dimensions of self-presence (i.e., proto-self-presence, core-self-presence, and extended-self-presence). The sample comprised 125 young adults aged between 18 and 29 years who underwent either (i) three offline measurements (1 month apart, over 3 months) or (ii) a cross-sectional online measurement. Regression and latent growth analysis indicated that the initial intensity of the physical, emotional, and identity self-presence aspects associated with IGD severity, but not to its longitudinal change. Overall, young adult gamers may exhibit higher IGD risk and severity when the experience of physical, emotional, and identity bonding with their in-game character is pronounced. The implications surrounding treatment and preventative policy recommendations are further discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mounting evidence suggests that disordered gaming presents many negative detriments to wellbeing for young adults, particularly among those aged between 18 and 29 years (Burleigh et al. 2018; Adams, Stavropoulos, Burleigh, Liew and Griffiths 2018; Scerri, Anderson, Stavropoulos, Hu and Collard 2018; Liew, Stavropoulos, Burleigh, Adams, and Griffiths 2018; Stavropoulos et al. 2019). Due to increasing empirical evidence, the World Health Organization (WHO 2018) recently suggested gaming disorder (GD) as a formal diagnosis in the beta draft of the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11, 2018). However, given the emphasis of current research concerning online and interactive gaming, the conceptualization of Internet gaming disorder (IGD) included in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA 2013) has been adopted for the present paper.

IGD reflects a pervasive and persistent form of Internet gaming, which leads to behavioral problems and distress capable of compromising how individuals function across several life domains (APA 2013; Stavropoulos et al. 2018c; Pontes et al. 2017). Furthermore, IGD risk appears to vary across different game genres (Stavropoulos et al. 2018b) and specific game genres may be risk factors for IGD. Online games such as massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPGs) have been found to pose as a risk factor for IGD (Stavropoulos, Kuss, Motti-Stefanidi, and Griffiths 2017) due to combining inbuilt features of progressively elevating demands and rewards, online socialization, and in-game character customization of avatars. More recently, research has highlighted avatar development and character building as an important and simultaneously under-investigated IGD risk factor (Liew et al. 2018; Burleigh et al. 2018; Adams et al. 2018). Therefore, the present study investigates the IGD risk effect of in-game character building aspects in the context of MMORPGs among young adults because this particular age group has been found to be at greater risk for IGD due to the simultaneous existence of higher impulse, increased independence, and elevated Internet use/access (Stavropoulos et al. 2018a, 2019).

In order to achieve this goal, the present study adopts the broadly accepted cyberpsychology theoretical framework of player-avatar bond introduced by Ratan (2013) for two main reasons. Firstly, this framework provides an integrative and multifaceted conceptualization of the user-avatar relationship. Secondly, it has been used in past IGD research and, therefore, it provides good justification for reliable construct comparisons with existing literature (e.g., Liew et al. 2018). According to this theoretical framework, self-presence (SP) holistically defines the extent to which elements related to gamers self-perceptions about their body, emotions, and identity interact (and interfere) with their online behavior. SP comprises the following three sub-dimensions: proto-self-presence (PSP), core-self-presence (CSP), and extended-self-presence (ESP). These dimensions are introduced to separately reflect the specific physical/body, emotion, and identity aspects of the player-avatar relationship respectively (Ratan and Hasler 2009). The different aspects of SP have been assumed to increase immersive gaming tendencies and avatar-attachment motivations that provide the ground for IGD behaviors to emerge and develop (Burleigh et al. 2018; Liew et al. 2018). Nevertheless, to date, the IGD risk effects of the different aspects of SP have not been investigated either concurrently or longitudinally. Consequently, investigating these aspects will greatly expand the knowledge base in IGD by highlighting the following: (i) how the different sub-dimensions of SP rank regarding their IGD-related effects and (ii) how they may influence the progress of IGD behaviors over time. Investigating this issue is paramount in enabling the differential allocation of psychological assessment and treatment emphasis on the three basis of the specific sub-dimensions of SP, helping improve prevention and intervention outcomes for IGD.

The Present Study

Despite previous research illustrating the user-avatar relationship as an IGD precursor, the associations of this relationship, as well as the effects on IGD over time, have not been investigated in greater depth by previous research. Consequently, the present study is (to the best of the authors’ knowledge) the first to employ Ratan’s SP theoretical framework to examine how the different aspects of SP (i.e., PSP, CSP, ESP) user-avatar associations may be related to IGD over time among MMORPG gamers in emergent adulthood. The present study investigated all sub-dimensions of SP in relation to IGD symptoms concurrently and over a 3-month period. The aim of the present pilot study was twofold: (i) to investigate the associations between physical, emotional, and identity aspects of self-presence associate and IGD severity, and (ii) to assess over-time IGD variations in relation to the three dimensions of self-presence (i.e., proto-self-presence, core-self-presence, and extended-self-presence).

Method

Participants

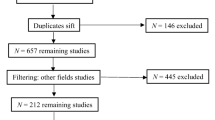

A normative sample comprising 125 young adults MMORPG gamers was recruited in the present study. Data were collected using both offline and online methods. More specifically, a total of 64 participants were assessed online once (Mage = 23.34, SD = 3.39, males = 49, 77.6%) and 61 participants completed a face-to-face [FtF] assessment over a period of 3 months (Mage = 23.02, SD = 3.43, males = 47, 75.4%). Both Internet and FtF T1 responses were mergedFootnote 1 in the cross-sectional analyses, while FtFFootnote 2 responses over time (i.e., time points 1, 2, 3 [T1, T2, T3]) were exclusively utilized to assess IGD growth patterns over 3 months to align with the commonly considered period of examining short-term changes in addictive behaviors (Stavropoulos et al. 2018b). Sociodemographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1. The estimated maximum sampling error for a sample of 125 is 8.77% and is considered within the recommended range (Anderson and Gerbing 1984).

Instruments

Two psychometric measures were utilizedFootnote 3 in addition to the collection of sociodemographic data.

Internet Gaming Disorder Scale—Short Form

(IGDS9-SF; Pontes and Griffiths 2015): The IGDS9-SF was utilized to assess IGD behaviors and the severity of its symptoms (Pontes and Griffiths 2015). The IGDS9-SF comprises nine items (e.g., “Do you systematically fail when trying to control or cease your gaming activity?”) assessing the nine IGD criteria defined by the APA in the DSM-5 (2013). All nine responded to a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = very often) and after summing up all individual responses, the total scores range from 9 to 45, where higher values suggest increased levels of IGD symptoms. In the present study, the reliability of the IGDS9-SF was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .92).

The Self-Presence Questionnaire

(SPQ; Ratan and Dawson 2016): The SPQ was utilized to assess proto (body; PSP), core (emotional; CSP), and extended (identity; ESP) SP aspects, as well as overall SP. This instrument comprises 13 self-report items (e.g., “When playing the game, how much do you feel like your avatar is an extension of your body within the game?”) that is responded to a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 4 = absolutely). The points on the different items are added to provide the total SP score (i.e., 13 items, ranging from 0 to 52), as well as the sub-dimensions of PSP (i.e., five items, ranging from 0 to 20), CSP (i.e., five items ranging from 0 to 20), and ESP (i.e., three items ranging from 0 to 12) with higher scores indicating higher levels of the different SP aspects experienced. In the present study, the internal reliability for overall SP as well as for PSP, CSP, and ESP indicators were all excellent (Cronbach’s α for PSP and ESP = .90 and Cronbach’s α for CSP and total SP = .91).

Data Collection and Statistical Analyses

Ethics permission was granted from the research team’s institutional ethics committee. MMORPG gamers from the community were invited to participate both offline via research participation calls and online via Facebook advertisements.Footnote 4 The FtF longitudinal data were collected over 3 months with identical monthly assessments (paired with an anonymized code) starting from June 2016.

For FtF data collection, young adult MMORPG gamers willing to participate were enrolled using a SurveyMonkey hyperlink available on MMORPG-relevant websites and portals (e.g., http://www.ausmmo.com.au). At the outset of the survey, participants were directed to a plain language information statement followed by the digital provision of informed consent before responding the questions. In order to ascertain the association patterns between SP and its unique aspects in relation to IGD, multiple linear regression and latent growth modeling (LGM) were conducted to explore these potential associations. With regard to the multiple linear regression analysis, due to collinearity (partial conceptual overlap of the IGD-effects of the total SP, PSP, CSP, and ESP), four two-step hierarchical multiple linear regression models were calculated to independently examine whether the total SP, PSP, CSP, and ESP self-reported rates associated to the IGD behaviors exhibited (in order to avoid collinearity risks). Age and gender (binary coded as 0 for females and 1 for males) were inserted in the first step of all models to control for their potential confounding effects, while the total and the different SP aspects were separately inserted in the second step of each of the four models to independently examine their associations with IGD. These analyses were conducted with bootstrapping using a total of 1000 re-samples across all four models to ensure the robustness the findings (Berkovits et al. 2000).

For the LGM analysis, four models were estimated using the overall SP scores, PSP, CSP, and ESP measured at Time 1 (T1) because growth moderators of IGD manifestations (time 1-invariant covariates of the IGD intercept and slope) across the three monthly FtF measurements were estimated with the employment of robust maximum likelihood using M-plus (Muthén and Muthén 2019). These models permitted IGD symptoms at different time points to be calculated, such that the mean and the variance of the intercept (the T1 rate of IGD symptoms) and the growth parameter (difference of IGD symptoms between measurements) were provided. For the LGM analysis, IGD symptoms at the three measurements were defined as 0, 1, and 2 respectively, to guide a linear growth calculation with equidistant measurements. Furthermore, the IGD symptoms intercept at the three measurements were defined as 0 and their residual variances were freely produced. The chi-square goodness of fitFootnote 5 (absolute fit), the root mean square error of approximationFootnote 6 (RMSEA incremental fit), the comparative fit indexFootnote 7 (CFI-incremental fit), the Tucker Lewis indexFootnote 8 (TLI-incremental fit), the Akaike information criterionFootnote 9 (AIC-information theory derived fit), and the Bayesian information criterionFootnote 10 (BIC-information theory–derived fit) were concurrently considered for model fit.

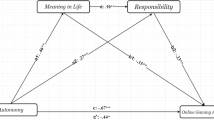

The Model fit of the four models (Models 1–4, with overall SP, PSP, CSP, and ESP separately used as time invariant moderators/covariates of the IGD intercept and growth) was later compared. The LGMs tested are shown in the diagrams presented below (see Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4). These comprised the IGD growth-curve, the IGD intercept (I), and the linear parameters (S) alongside the moderators/covariates of SP, PSP, CSP, and ESP used sequentially for Models 1–4. The observed outcomes reflected the three monthly IGD symptoms assessments (T1–T3).

Results

After estimating the aforementioned multiple linear regression models, the results indicated that the slopes of the regression lines were statistically significant for all four models (SP, F(3, 120) = 15.03, p < .001; PSP, F(3, 120) = 13.13, p < .001; CSP, F(3, 120) = 9.14, p < .001; ESP, F(1, 123) = 18.45, p < .001). With regard to the overall effects, 26%, 25%, 19%, and 15% of the variance of IGD behaviors was exclusively associated to the addition of SP, PSP, CP, and ESP at the second step of the examined models respectively (SP R2 = .26; PSP R2 = .25; CSP R2 = .19; and ESP R2 = .15). The standardized coefficients (β) indicated that one standard deviation increase in SP, PSP, CSP, and ESP would lead to a .50, .45, .39, and .36 standard deviation change in the IGD symptoms (SP b = .37, SE(b) = .06, β = .50, t = 6.04, p = .001; PSP b = .78, SE(b) = .14, β = .45, t = 5.58, p = .001; CSP b = 1.07, SE(b) = .24, β = .39, t = .4.44, p = .000; ESP b = .52, SE(b) = .13, β = .36, t = 4.16, p = .001) respectively.

The LGMs analysis were subsequently conducted and the results are summarized in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4. The IGD mean (and IGD standard deviation) across the three measurements were 19.49 (7.02), 18.71 (6.84), and 17.93 (5.91). As previously mentioned, four models examining separately the effects of the different aspects of SP (SP overall, PSP, CSP, and ESP) were calculated. All aspects of SP (SP overall, PSP, CSP, and ESP) initially assessed did not significantly predict IGD changes over the time period examined. Nevertheless, all the different aspects of SP were found to be significantly related to the IGD intercept (SP overall b = .31; p < .001; PSP b = .69; p < .001; CSP b = 1.14; p < .001; ESP b = .422; p = .004). Therefore, while all four LGMs tested had sufficient fit (see Table 2) and all the different aspects of SP were found to be associated with IGD at T1, they did not meaningfully relate with the IGD rate-of-change across the 3 months investigated. Based on AIC and BIC comparisons, it is suggested that (aside from Model 1 that assessed SP overall as an IGD intercept and growth covariate) the model that involved CSP as a growth covariate/moderator resulted to improved fit in relation to the model with PSP as a growth covariate/moderator, which in turn had better fit than the model with ESP as a growth covariate/moderator (see Table 2).

Discussion

The present study utilized Ratan’s (2013) theoretical model of self-presence (SP) to comparatively investigate the likely risk effects of the different aspects of SP in relation to the body, emotional, and identity gamer-avatar relationship in the context of Internet gaming disorder (IGD), concurrently and longitudinally (across a 3-month period). In consensus with the extant literature, young adult MMORPG players showing increased overall SP, PSP, CSP, and EPS exhibited greater levels of IGD symptoms (Burleigh et al. 2018; Adams et al. 2018; Liew et al. 2018; Ortiz de Gortari et al. 2015). Nevertheless, and aside from the 26% of the IGD symptoms’ variance being associated to overall SP, the IGD effects of the SP sub-aspects differed (when separately examined). More specifically, PSP appeared to contribute more to IGD variance (25%) than CSP (19%) and ESP (15%). The comparative examination of these results indicates that while overall SP, as well as all its three sub-aspects, are associated with significant IGD risk, it is the body-bond aspect (PSP) of the user-avatar association that appears to relate more to IGD behaviors than the emotional (CSP) and the identity (ESP) aspects of SP.

These findings can be contextualized within the broad range of experiences related to non-volitional phenomena associated with playing games. Game Transfer Phenomena (GTP) has been extensively investigated in videogame research (e.g., Dindar and Ortiz de Gortari 2017; Ortiz de Gortari et al. 2015) and is defined as non-volitional phenomena such as altered perceptions, automatic mental processes, and involuntary behaviors that occur among players inside and outside of the game (Ortiz de Gortari and Griffiths 2015). Accordingly, GTP can be manifested as altered sensorial perceptions including the experience of bodily sensations within video games (Ortiz de Gortari and Griffiths 2015). Additionally, severe levels of GTP has been associated with long gaming sessions and dysfunctional patterns of gaming because those with severe levels of GTP share characteristics with profiles of disordered gamers (Ortiz de Gortari et al. 2016).

Although the regression models indicated overall SP, as well as its three sub-aspects, were significantly associated to IGD behaviors, the four LGM models calculated were not suggestive of either the overall SP or its three sub-dimensions (experienced) being significantly associated with IGD behaviors variations during the 3-month period examined. This finding could be indicative of several explanatory possibilities. First, confounding effects (e.g., comorbid psychopathology or attachment styles of the user) might interfere with the overall SP (and its sub-aspects [i.e., PSP, CSP, and ESP]) relationship with IGD symptoms (Stavropoulos et al. 2019). Second, methodology-related limitations may have interfered with this finding. More specifically, such limitations could relate to the relatively short (3-month period) investigation conducted (Stavropoulos et al. 2018b). Moreover, it is possible that longer time periods are required for significant overall associations to be detected between SP, PSP, CSP, ESP, and IGD. Therefore, it is suggested that the results of the present study should be treated as an initial stage of the investigation concerning the longitudinal associations between SP and its associated aspects in relation to IGD symptoms and their temporal variations.

Researchers and clinicians in the field should therefore implement parallel growth curve calculations in future research studies because such models would provide information concerning how the potential rates of growth in overall SP, PSP, CSP, and ESP are associated with the rate of IGD change longitudinally (growth factors of overall SP, PSP, CSP, ESP, and IGD growth factor). It is noted that the limited number of participants employed in the present study (i.e., lack of model-convergence) did not enable the examination of parallel growth conceptualizations in the present study. Despite these potential limitations, the results presented here may suggest meaningful treatment and prevention suggestions for young adult MMORPG gamers either presenting with or being at-risk for developing IGD.

Furthermore, a closer attachment developed between the gamer and their in-game avatar, especially from a body-connection perception perspective (PSP), might exacerbate the length of game sessions and game-character immersion, resulting in higher dysfunctionality across several everyday life domains (e.g., personal relationships, education, and/or occupation; Burleigh et al. 2018; Adams et al. 2018; Liew et al. 2018). This finding is consistent with research conducted concerning in-game avatar attachment and identification (Leménager et al. 2016; Mancini et al. 2019) because greater levels of avatar attachment and identification have been found to be risk factors for IGD (Burleigh et al. 2018; You et al. 2017). Therefore, the perception and experience of the self by the user being bonded (especially from a bodily perspective) with the avatar might need to be accounted for in therapeutic situations because IGD behaviors are interwoven with known avatar-related motivational factors (i.e., avatar performance-related self-esteem, identification, and immersion tendencies; Burleigh et al. 2018; Adams et al. 2018; Liew et al. 2018). Self-presence and immersion-identification with one’s in-game self are expected to continue being significant within the gaming world via constant and rapid technological advancements (i.e., realistic in-game self-representations; Stavropoulos et al. 2019). Therefore, SP-related aspects should be emphasized within the clinical and treatment contexts to clarify their effects on a user’s propensity to involve and prolong their MMORPG participation in spite of detrimental effects due to disordered gaming.

Despite its relevant value, the present study has a number of limitations that need to be taken into account when interpreting its results. These limitations involve mainly sample, time, and assessment-related limitations. For instance, the relatively small number of the gamers recruited, their volunteering role, and the over-representation of males limit the generalizability of the conclusions made. Considering time-related limitations, the 3-month period investigated may not be long enough to fully delineate the associative relationships targeted (Stavropoulos et al. 2018b). Furthermore, random effects in relation to game exposure (i.e., game playing history) were not controlled for. Finally, the assessment methods used comprised self-report measures that were completed by the participants, and therefore are subject to several biases (i.e., social compliance, selective memory).

In the context of these limitations, the strengths of the current work need to be acknowledged. These involve the combination of online and FtF participants, cross-sectional and longitudinal models, as well as comparatively assessing the effects of the different aspects of the user-avatar bond within an accepted theoretical framework of SP (Ratan 2009; Ratan and Dawson 2016. Further research in this area would likely enhance the available knowledge in the field by emphasizing on the need to examine the longitudinal interactions of relevant in-game factors, such as online flow and immersion. Finally, possible IGD resources associated to the gamers and their offline surroundings and relationships (i.e., romantic and friends’ context) might be fruitful in advancing a more comprehensive understanding of IGD behaviors (Stavropoulos et al. 2017).

Data Availability

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Notes

To examine potential differences between the Internet and FtF respondents related to their sociodemographic and Internet behaviors, independent sample t tests and chi-square analyses were conducted. The results yielded non-significant variations considering participants’ gender (X2 = .21, df = 1, p = .89), chronological age (t = −.54, df = 120, p = .59) and history of Internet use (t = 2.35, df = 122, p = .06). Accordingly, Internet and FtF responses (i.e., TP1) were merged for the cross-sectional results.

The attrition of the longitudinal data collection across the three waves during 3months in the FtF measurements was examined. The measurements’ frequency per respondent was situated within a range of 1–3 (Maverage = 2.57). T1 involved 61 respondents, while T2 involved 56 participants (8.20% attrition) and T3 included a total of 43 respondents (29.51% attrition). Attrition across all three waves was deemed non-problematic according to Missing Completely At Random test (MCAR X2 = 1715.79, p = 1.00; Little 1988). Therefore, maximum likelihood imputation (five times) of missing values was conducted (Newman 2003).

The present research belongs to a broader project examining the interactions of gamer and game-related influences in the emergence of IGD behaviors among young adults, MMO gamers. Instruments used in the data include the following: (1) Internet Gaming Disorder 9- Short Form (Pontes and Griffiths 2015); (2) Beck Depression Inventory II

(Beck et al. 1996); (3) Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck and Steer 1990); (4) Hikikomori-Social Withdrawal Scale (Teo et al. 2015); (5) Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Self-Report Scale (Kessler et al. 2005); (6); Ten Item Personality Inventory (Gosling et al. 2003); (7) The Balanced Family Cohesion Scale (Olson 2000); (8) Presence Questionnaire (Faiola et al. 2013); (9) Online Flow Questionnaire (Chen et al. 2000) (10) Self-Presence Questionnaire (Ratan and Hasler 2009; Ratan and Dawson 2016; (11) The Gaming-Contingent Self-Worth Scale (Beard and Wickham 2016); and (12) Demographic and Internet Use Questions. The above sequence of self-reported scales was administered for Internet and FtF respondents, while a fitness tracker (Fitbit flex) was additionally employed to monitor physical activity in the FtF collection mode. Different parts of the data have been used to answer different research aims in the four previously published studies by Burleigh et al. 2018; Adams, Stavropoulos, Bulreigh, Liew and Griffiths 2018; Liew, Stavropoulos, Burleigh, Adams and Griffiths 2018; Stavropoulos, Burleigh, Beard, Gomez and Griffiths 2018b).

Abiding to the ethical permission granted, the research advertisements (a) described that respondents were requested to address the survey at three occasions, 1 month apart each; (b) provided email correspondence to be contacted when necessary; and (c) clearly defined the data collection modes and stages (FtF and Internet). Young adult MMO gamers willing to be enrolled first accessed the Plain Language Information Statement (PLIS). This clarified and indicated that the survey was voluntary and that respondents could interrupt their participation at any point. Gamers who chose to take part were first requested to confirm their informed consent.

If the chi-square is insignificant, it indicates a good model fit because the observed and the model produced covariance matrices do not significantly differ. Nevertheless, this indicator is dismissed in sample sizes exceeding 200 and when multivariate normality is absent.

The RMSEA reflects the square root of the average regarding the residual differences between the observed and the model produced covariance matrices. Zero suggests an excellent fit. In general, RMSEA rates lower than .08, and in an optimum case, lower than .05 are considered sufficient (Hu and Bentler 1999).

The CFI compares the calculated model with the null model. In particular, the CFI describes the level at which the calculated mode provides a better solution than the null model. The closer CFI is to 1, the better the fit, with values in the area above .90 indicating sufficient fit. It is noted that CFI is less sensitive to sample size variations (Marsh et al. 1988).

The TLI is associated to the ratio of the chi-square for the model of reference and the null model and their associated df values that are then subtracted from each other and their difference is finally divided by the null model chi-square minus 1. As with CFI, TLI values in the range between .90 and .95 are considered sufficient, while they tend not to fluctuate due to sample size (Marsh et al. 1988).

The AIC constitutes an information theory–derived fit indicator, which is employed when maximum likelihood estimation is conducted. Similar to the chi-square, the AIC describes the rate of difference between the observed and model-related covariance matrices with lower values indicating better fit (Hu and Bentler 1999).

The BIC, as the AIC, derives from information theory and refers to the log of a Bayes factor of the calculated model in contrast to the saturated model, while penalizing against more complex models and smaller samples (Burham and Anderson 2004).

References

Adams, B. L., Stavropoulos, V., Burleigh, T. L., Liew, L. W., Beard, C. L., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Internet gaming disorder behaviors in emergent adulthood: a pilot study examining the interplay between anxiety and family cohesion. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction., 17, 828–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9873-0.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1984). The effect of sampling error on convergence, improper solutions, and goodness-of-fit indices for maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis. Psychometrika, 49(2), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294170.

Beard, C. L., & Wickham, R. E. (2016). Gaming-contingent self-worth, gaming motivation, and internet gaming disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.046.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Manual for the Beck anxiety inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A., Steer, R., & Brown, G. (1996). BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory: Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Berkovits, I., Hancock, G. R., & Nevitt, J. (2000). Bootstrap resampling approaches for repeated measure designs: Relative robustness to sphericity and normality violations. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(6), 877–892. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640021970961.

Burleigh, T. L., Stavropoulos, V., Liew, L. W., Adams, B. L., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Depression, internet gaming disorder, and the moderating effect of the gamer-avatar relationship: An exploratory longitudinal study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(1), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9806-3.

Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2004). Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods & Research, 33(2), 261–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644.

Chen, H., Wigand, R. T., & Nilan, M. (2000). Exploring web users’ optimal flow experiences. Information Technology & People, 13(4), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/09593840010359473.

Dindar, M., & Ortiz de Gortari, A. B. (2017). Turkish validation of the game transfer phenomena scale (GTPS): Measuring altered perceptions, automatic mental processes and actions and behaviours associated with playing video games. Telematics and Informatics, 34, 1802–1813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.09.003.

Faiola, A., Newlon, C., Pfaff, M., & Smyslova, O. (2013). Correlating the effects of flow and telepresence in virtual worlds: Enhancing our understanding of user behavior in game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1113–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.003.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Ames, M., Demler, O., Faraone, S., Hiripi, E. V. A., & Ustun, T. B. (2005). The world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 35(02), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704002892.

Lemenager, T., Dieter, J., Hill, H., Hoffmann, S., Reinhard, I., Beutel, M., & Mann, K. (2016). Exploring the neural basis of avatar identification in pathological internet gamers and of self-reflection in pathological social network users. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5, 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.048.

Liew, L. W., Stavropoulos, V., Adams, B. L., Burleigh, T. L., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Internet gaming disorder: The interplay between physical activity and user–avatar relationship. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37(6), 558–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1464599.

Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722.

Mancini, T., Imperato, C., & Sibilla, F. (2019). Does avatar’s character and emotional bond expose to gaming addiction? Two studies on virtual self-discrepancy, avatar identification and gaming addiction in massively multiplayer online role-playing game players. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.007.

Marsh, H. W., Balla, J. R., & McDonald, R. P. (1988). Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 391–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.391.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2019). Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: User’s guide 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Newman, D. A. (2003). Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods, 6(3), 328–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428103254673.

Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 144–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00144.

Ortiz de Gortari, A. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Game transfer phenomena and its associated factors: An exploratory empirical online survey study. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.060.

Ortiz de Gortari, A. B., Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). The game transfer phenomena scale: An instrument for investigating the nonvolitional effects of video game playing. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 18(10), 588–594. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0221.

Ortiz de Gortari, A. B., Oldfield, B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). An empirical examination of factors associated with game transfer phenomena severity. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.060.

Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Measuring DSM-5 Internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143.

Pontes, H. M., Stavropoulos, V., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Measurement invariance of the internet gaming disorder scale–short-form (IGDS9-SF) between the United States of America, India and the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Research, 257, 472–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.013.

Ratan, R. (2013). Self-presence, explicated: body, emotion, and identity extension into the virtual self. In: Handbook of research on technoself: identity in a technological society (pp. 322–336). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Ratan, R. A., & Dawson, M. (2016). When Mii is me: A psychophysiological examination of avatar self-relevance. Communication Research, 43(8), 1065–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215570652.

Ratan, R. A., & Hasler, B. (2009). Self-presence standardized: introducing the Self-Presence Questionnaire (SPQ). In Proceedings of the 12th Annual international Workshop on Presence. Los Angeles, CA, USA, November 11-13, 2009.

Ratan, R. A., & Hasler, B. (2009). Self-presence standardized: Introducing the self-presence questionnaire (SPQ). In Proceedings of the 12th annual international workshop on presence (Vol. 81).

Scerri, M., Anderson, A., Stavropoulos, V., & Hu, E. (2018). Need fulfilment and internet gaming disorder: a preliminary integrative model. Addictive Behaviors Reports. Epub ahead of print. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100144, 9, 100144.

Stavropoulos, V., Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., Wilson, P., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2017). MMORPG gaming and hostility predict Internet addiction symptoms in adolescents: An empirical multilevel longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.001.

Stavropoulos, V., Anderson, E. E., Beard, C., Latifi, M. Q., Kuss, D., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018a). A preliminary cross-cultural study of hikikomori and internet gaming disorder: The moderating effects of game-playing time and living with parents. Addictive Behaviors Reports., 9, 100137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.10.001.

Stavropoulos, V., Burleigh, T. L., Beard, C. L., Gomez, R., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018b). Being there: a preliminary study examining the role of presence in internet gaming disorder. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 880–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9891-y.

Stavropoulos, V., Beard, C., Griffiths, M. D., Buleigh, T., Gomez, R., & Pontes, H. M. (2018c). Measurement invariance of the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short-Form (IGDS9-SF) between Australia, the USA, and the UK. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(2), 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9786-3.

Stavropoulos, V., Adams, B. L., Beard, C. L., Dumble, E., Trawley, S., Gomez, R., & Pontes, H. M. (2019). Associations between attention deficit hyperactivity and internet gaming disorder symptoms: Is there consistency across types of symptoms, gender and countries? Addictive Behaviors Reports, Epub ahead of print., 9, 100158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100158.

Teo, A. R., Fetters, M. D., Stufflebam, K., Tateno, M., Balhara, Y., Choi, T. Y., & Kato, T. A. (2015). Identification of the hikikomori syndrome of social withdrawal: Psychosocial features and treatment preferences in four countries. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014535758.

World Health Organization (2018). International classification of diseases (11th ed.). Beta draft. Geneva: World Health Organization.

You, S., Kim, E., & Lee, D. (2017). Virtually real: Exploring avatar identification in game addiction among massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) players. Games and Culture, 12(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015581087.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author 1 contributed to the literature review, hypotheses formulation, data collection and analyses, and the structure and sequence of theoretical arguments.

Author 2 contributed to the literature review, hypotheses formulation, data collection and analyses, and the structure and sequence of theoretical arguments.

Author 3 contributed to literature review, hypotheses formulation, data collection and analyses, and the structure and sequence of theoretical arguments.

Author 4 contributed to the theoretical consolidation of the current work and revised and edited the final manuscript.

Author 5 contributed to literature review, hypotheses formulation, data collection and analyses, and the structure and sequence of theoretical arguments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of University’s Research Ethics Board and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Confirmation Statement

Authors confirm that this paper has not been either previously published or submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Stavropoulos, V., Dumble, E., Cokorilo, S. et al. The Physical, Emotional, and Identity User-Avatar Association with Disordered Gaming: A Pilot Study. Int J Ment Health Addiction 20, 183–195 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00136-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00136-8