Abstract

Over the past decade, the use of social media applications have increased worldwide. In parallel with this, abuse of social media has also increased. In recent years, many disorders related to social media use have been conceptualized. One of the common consequences of these disorders is the intense desire (i.e., craving) to use social media. The aim of the present study was to develop the Social Media Craving Scale (SMCS) by adapting the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS). The study comprised 423 university students (242 females and 181 males) across five different samples. The psychometric instruments used included the Social Media Craving Scale, Social Media Disorder Scale, Brief Self-Control Scale, and Personal Information Form. In the present study, structural validity and reliability of the SMCS were investigated. The structural validity of SMCS was investigated with Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and criterion validity. The reliability of SMCS was evaluated using Cronbach α internal consistency reliability coefficient, corrected item total correlation coefficients, and test-retest method. As a result of EFA, the SMCS was found to be unidimensional scale. This unidimensional structure explained approximately half of the total variance. The unidimensional structure of SMCS was tested in two different samples with CFA. As a result of CFA, SMCS models were found to have acceptable fit values. The criterion validity of the SMCS was evaluated by assessing social media disorder, self-discipline, impulsiveness, daily social media use duration, social media usage history, frequency of checking social media accounts during the day, number of social media accounts, and number of daily shares. Analysis demonstrated that the SMCS was associated with all these variables in the expected direction. According to the reliability analysis (Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficients, corrected item total correlation coefficients, and test-retest method), the SMCS was found to be a reliable scale. When validity and reliability analyses of the SMCS are considered as a whole, it is concluded that the SMCS is a valid and reliable scale in assessing social media craving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past 20 years, worldwide internet use has increased. As of 2018, more than half of the world’s population has access to the internet. This number is reported to be approximately four billion (Kemp 2018). Coupled with this, the use of social media has also increased. According to the current data, 39% of the world’s population is an active mobile social media user (Kemp 2018). The average use of social media in Turkey (where the present study was carried out) appears to be above the world average with 63% of Turkey’s population being active social media users. In addition, the internet is often used for social media in Turkey (Kemp 2018; Turkish Statistical Institute, 2017). As of 2018, the average daily use of social media in Turkey was 2 h and 48 min. Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, WeChat, QQ, and Instagram are reported as the most popular social media applications respectively (Kemp 2018).

As the use of social media applications has increased, social media abuse has also increased. In the literature, a number of alleged disorders arising from social media have been conceptualized including social media addiction (Andreassen et al., 2017), social media disorder (Savci and Aysan 2018), excessive social media use (Griffiths and Szabo, 2014), problematic social media use (Meena et al., 2012), compulsive social media use (De Cock, Vangeel, Klein, Minotte, Rosas, and Meerkerk 2014) and pathological social media use (Holmgren and Coyne 2017). Although there are differences in names, there appear to be common criteria for social media use disorders. Most of these conceptualizations emphasize salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, conflict, and relapse. Indeed, scholars such as Griffiths (2013) identify social media addiction with these six criteria. In addition, van den Eijnden, Lemmens, and Valkenburg (2016) identifies social media disorder/addiction using nine criteria (preoccupation, tolerance, withdrawal, persistence, displacement, problems, deception, escape, and conflict). Although social media addiction is not formally classified in the latest (fifth) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) it has been conceptualized as a behavioral addiction in the literature (Andreassen and Pallesen 2014; Griffiths 2013; Kuss and Griffiths 2011a; Griffiths, Kuss, and Demetrovics 2014).

Behavioral addictions can be similar to substance addictions in many ways including natural history, phenomenology, tolerance, comorbidity, overlapping genetic contribution, neurobiological mechanisms, and response to treatment (Grant, Potenza, Weinstein, and Gorelick 2010; Griffiths 1996; Griffiths 2005). In addition, behavioral addictions typically involve an urge or craving prior to engagement in the addictive behavior, similar to substance addictions (Grant et al. 2010). In this context, the empirical research demonstrates that social media addiction has common characteristics with both behavioral and chemical addictions (Griffiths et al. 2014; He, Turel, and Bechara 2017; Hormes, Kearns, and Timko 2014).

Social media addiction has been defined in the literature in different ways. Social media addiction has been defined as the problematic excessive use of social media comprising (i) an increase over time in the desire to use social media, (ii) important educational and/or occupational activities being neglected, (iii) harming personal relationships, (iv) using social media to escape from daily life stress and negative emotions, (v) experiencing problems in reducing or stopping social media use, (vi) becoming tense and irritable when social media cannot be used, and (vii) lying about the duration of social media use (Griffiths et al. 2014; Griffiths 2013; Kuss and Griffiths 2011a; Kuss and Griffiths 2011b; Savci and Aysan 2018; van den Eijnden et al. 2016). Research has shown that social media addiction is related to psychopathology (Hormes et al. 2014; Koc and Gulyagci 2013; Meena et al. 2012; Pantic et al. 2012), reward and punishment systems (He et al. 2017; Savci and Aysan 2018), sleep disorders (Levenson, Shensa, Sidani, Colditz, and Primack 2016; Woods and Scott 2016), academic performance (Huang 2013; Huang and Leung 2009), loneliness (Huang and Leung 2009; Savci and Aysan 2018; Yıldız-Durak 2018), narcissistic personality (Andreassen et al. 2017; Ryan and Xenos 2011), behavioral addiction (Griffiths 2013), impulsivity (Savci and Aysan 2016), relationship dissatisfaction (Elphinston and Noller 2011), social connectedness (Savci and Aysan 2017; Savci, Ercengiz, and Aysan 2018), and disorders related to the use of digital technology such as internet addiction (Guedes et al. 2016), fear of missing out (Blackwell, Leaman, Tramposch, Osborne, and Liss 2017), internet gaming disorder (Pontes 2017), and phubbing (Karadağ et al. 2015). In this context, it can be said that social media addiction has a broad etiological spectrum.

Social media has important functions in establishing close relationships, seeking new social networks, and initiating and maintaining relationships. Individuals have the opportunity to easily share their thoughts, feelings, mood, and status with others via social media. Social media can show that people are liked, approved, and accepted within a short timeframe (Savci and Aysan 2018). Even if there is no problematic social media use, the desire and craving to use social media can still emerge as a result of these social functions. However, the desire and craving to use social media derives from the addiction literature (Griffiths 2013; Griffiths et al. 2014; Kuss and Griffiths 2011a). Furthermore, the desire to use social media has been conceptualized as a craving for social media (Hormes et al. 2014). More generally, craving defined as “a strong desire/urge” to use a substance (APA 2013) or as “a strong desire or sense of compulsion” to use a particular substance (World Health Organization [WHO] 1993). Although the concept of craving has traditionally been used for substance abuse and dependence, it has increasingly been used for behavioral addictions in recent years (Grant et al. 2010). Craving has started to play an important role in behavioral addictions such as gambling addiction (Young and Wohl 2009), internet gaming disorder (Dong, Wang, Du, and Potenza 2017; Shin et al. 2018), pornography addiction (Kraus and Rosenberg 2014), food addiction (Rogers and Smit 2000) and social media addiction (Hormes et al. 2014; Turel and Bechara 2016; Wegmann, Stodt, and Brand 2015). Therefore, it can be said that the concept of craving is not limited to substance abuse and dependence.

There are numerous scales in the literature that assess disorders related to social media use including (among others) the Facebook Addiction Scale (Andreassen, Torsheim, Brunborg, and Pallesen 2012), Social Media Disorder Scale (Savci and Aysan 2018; van den Eijnden et al. 2016), Social Media Addiction Scale (Ağyar-Bakır and Uzun 2018), Compulsive Social Networking Scale (De Cock et al. 2014), Excessive Social Media Use Scale (He, Turel, and Bechara 2018), and Instagram Addiction Scale (Kircaburun and Griffiths 2018). There are also scales related to social media craving in the literature. Wegmann et al. (2015) modified the Internet Addiction Scale (Pawlikowski, Altstötter-Gleich, and Brand 2013) to the Specific Internet Addiction-Social Networking Sites Scale (SIA-SNSS). One of the subscales of SIA-SNSS assesses social media craving. However, the validity and reliability of the SIA-SNSS were only examined using the Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient. Similarly, Hormes et al. (2014) modified the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS) (Flannery, Volpicelli, and Pettinati 1999) as the PACS-Facebook Addiction Scale (PACS-FBS). Again, the validity and reliability of the PACS-FBS were only examined using a Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient and the adapted scale only examined craving for Facebook use rather than social networking sites more generally. Therefore, there is a need for a measurement tool that assesses all social media craving with greater validity and reliability. Turel and Bechara (2016) modified the Alcohol Craving Experience (ACE) questionnaire (Statham et al. 2011) as Facebook Craving Experience (FaCE) questionnaire. They examined the validity and reliability of the FaCE via content validity, predictive validity, and an internal consistency coefficient. Again, this only assessed craving for Facebook use and not social media use more generally. Therefore, more robust scales related to social media craving are needed with greater reliability and validity assessments.

In this context, valid and reliable scales that assess social media craving can contribute to increasing the quality of research into social media craving including cross-cultural research. In addition, such scales could contribute to studies related to the diagnosis and treatment of disorders related to social media use. In this respect, the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale is a practical scale that has been adapted to other cultures (Chodkiewicz et al. 2018; Evren, Flannery, Çelik, Durkaya, and Dalbudak 2008; Kim et al. 2008; Pérez Gálvez, De Juan-Gutiérrez Maroto, García Fernández, Cabot Ivorra, and De Vicente Manzanaro 2016). The primary aim of the present study was to adapt and validate a Turkish version of the PACS to assess craving among social media users.

Methods

Participants

The study comprised on 423 university students (242 females and 181 males) across five different samples. A pilot study analysis was carried out with 45 students (33 females and 12 males). A structural validity study was carried out with 310 students (169 females and 141 males) across three different samples. Structural validity was carried out with Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), and a criterion validity analysis. A test-retest reliability analysis was carried out with 68 university students (40 females and 28 males). Demographic data relating to the study’s five sets of analyses are presented in Table 1.

Materials

Social Media Craving Scale

In the present study, the PACS developed by Flannery et al. (1999) was adapted to become the Social Media Craving Scale (SMCS). The five-item PACS is a self-report measure that asks participants to rate the intensity, frequency, and duration of their craving, and ability to resist acting on their craving for a stated period of time (in relation to alcohol use). The PACS also assesses the general craving for during the past week. High scores on the scale indicate high levels of alcohol craving. The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliability coefficient for PACS was calculated to be .92. The criterion validity of the PACS was assessed with obsessive-compulsive drinking, alcohol urge addiction severity, and adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. The predictive validity of the scale was based on relapse. When validity and reliability analysis of the PACS are considered as a whole, it is concluded that the PACS is a valid and reliable scale that assesses alcohol craving and was adapted to Turkish by Evren et al. (2008) for alcohol-addicted men.

Social Media Disorder Scale

The Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS), which was developed by van den Eijnden et al. (2016) and adapted to Turkish by Savci et al. (2018), is a Likert-type scale comprising nine items and is unidimensional. As a result of EFA conducted by Savci et al. (2018), the unidimensional SMDS was found to explain 47.9% the total variance of 47.88%. This unidimensional structure was tested with CFA in two separate samples. As a result of the analysis, it was found that the SMDS model had good fit values in both samples [(χ2 = 39.24, df = 27, χ2/df = 1453, RMSEA = .055, GFI = .95, AGFI = .91, CFI = .97, IFI = .97, and TLI (NNFI) = .96, (χ2 = 50.725, df = 26, χ2/df = 1.951, RMSEA = .072, GFI = .94, AGFI = .90, CFI = .94, IFI = .94, and TLI (NNFI) = .92]. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the SMDS was calculated in three different samples. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the SMDS was determined as .83, .86, and .86, and the 3-week test-retest correlation was .81. High scores indicate an increased risk of social media/addiction (Savci et al. 2018). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .86.

Brief Self-Control Scale

The Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS), developed by Tangney, Baumeister, and Boone (2004) and adapted into Turkish by Nebioglu, Konuk, Akbaba, and Eroglu (2012), comprises nine items and two dimensions (impulsiveness and self-discipline). The BSCS is a 5-point Likert-type scale. As a result of CFA conducted by Nebioglu et al. (2012), the BSCS was found to have perfect fit indices (χ2/df = 1.98, CFI = .98, GFI = .99, and RMSEA = .043). Cronbach’s α internal consistency reliability coefficients of the BSCS ranged between .81 and .87. High scores indicate a high level of impulsivity and self-discipline (Nebioglu et al. 2012). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .76.

Procedure

The development of the SMCS and data collection was approved by the research team’s university Ethics Committee. For the translation of the SMCS, two groups of researchers carried out the translation process. The first group translated the items of the PACS into Turkish. The second group then translated the Turkish version back into English. At this stage, the consistency between two translations was examined. The discrepancies in translations were forwarded to the translation groups leading to a consensus on the translation. Following this, the draft form was revised as the SMCS. In the SMCS, the words “social media using” were used instead of the word “drinking” [(see Appendix 1 (Turkish) and Appendix 2 (English)]. Four researchers conducting research into digital technology abuse examined the adapted form. After confirmation from this group, the trial form of the SMCS was developed. In the final stage, the SMCS was evaluated by 45 university students (33 females and 12 males). Participants did not report any problems using the SMCS.

The structural validity of the SMCS was examined with EFA, CFA, and criterion validity. Firstly, the dataset was examined as to whether it was suitable for EFA and it was found that it was. The SMCS was then tested with CFA. Before starting CFA, it was examined whether the data set suitable for CFA (sample size, multiple linearity, multicollinearity, and multiple normality). As a result of the evaluation, it was found that the dataset was suitable for CFA. Therefore, Maximum Likelihood method was used in CFA. In order to assess the model fit, fit indices (as outlined in Table 2) were considered. The criterion validity of the SMCS was assessed with the SMDS, BSCS (self-discipline, impulsiveness), daily social media use duration, social media usage history, frequency of checking social media accounts during the day, number of social media accounts, and number of daily shares on social media. The reliability of the SMCS was analyzed using Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficients, corrected item total correlation coefficients, and test-retest method. SPSS and AMOS programs were used to analyze the data.

Results

Pilot Study

A pilot study was carried out on 45 university students (33 females and 12 males) in order to assess whether students understand the SMCS. Results demonstrated that the students easily understood the instructions, scale items, and response options.

Scale Validity

Exploratory Factor Analysis

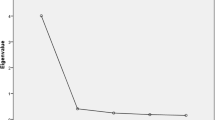

The structural validity of SMCS was first examined with EFA. EFA was carried out on 105 university students (59 females and 46 males). Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) coefficient and Barlett’s Sphericity Test were performed to determine whether or not EFA was applied to these data. As a result of the analysis, it was found that the dataset was suitable for EFA [(Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) coefficient = .80, Barlett’s Sphericity Test (χ2) = χ2 = 172.864 p < .001)]. Following this, EFA was performed on five items using basic component analysis. As a result of EFA, the scale was found to be single-factor (eigenvalue = 2.788). This single-factor structure explained 55.752% of the total variance. In order to determine the factor number of SMCS, the line graph in Fig. 1 was examined. This demonstrates that SMCS comprised a single factor. The factor loading values of the SMCS ranged between .38 and .86. The scree plot of the SMCS is presented in Fig. 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The one-dimensional SMCS structure determined by EFA was then tested with CFA. The CFA was used to test whether a model has been confirmed. CFA was carried out on 106 students (76 females and 30 males). The five-item one-dimensional structure of SMCS was tested with first-level CFA. In the analysis, it was found that the social media craving model had excellent fit index values [(χ2 = 6.328, df = 5, χ2/df = 1.266, RMSEA = .050, GFI = .98, AGFI = .94, CFI = .99, IFI = .99, and TLI (NNFI) = .99]. The factor loadings of SMCS for CFA ranged between .54 and .88. The path diagram of SMCS in the CFA sample is presented in Fig. 2. The five-item one-dimensional structure of SMCS was also tested on the data collected for criterion validity. As a result of the CFA, the SMCS model was found to be good fit except for RMSEA and TLI (NNFI). [(χ2 = 15.743, df = 5, χ2/df = 3.149, RMSEA = .148, GFI = .95, AGFI = .85, CFI = .94, IFI = .94, and TLI (NNFI) = .89]. The factor loadings values of SMCS in this sample were between .49 and .87. The path diagram in this sample of SMCS is presented in Fig. 3. These findings indicate that SMCS was confirmed in different samples. The CFA results are shown in Table 3.

Criterion Validity

The criterion validity of the SMCS was carried out on a sample of 99 adolescents (80 females and 43 males). The criterion validity of the SMCS was assessed using the SMDS, BSCS (self-discipline, impulsiveness), and self-reported personal information (daily social media use duration, social media usage history, frequency of checking social media accounts during the day, number of social media accounts, and number of daily shares on social media use). It was found that the SMCS was significantly associated with social media addiction (r = .67, p < .01), self-discipline (r = − .29, p < .01), impulsiveness (r = .44, p < .01), daily social media use duration (r = .64, p < .01), social media usage history (r = .39, p < .01), frequency of checking social media accounts during the day (r = − .36, p < .01), number of social media accounts (r = .48, p < .01), and number of daily shares on social media (r = .40, p < .01).

Scale Reliability

The reliability of SMCS was analyzed using Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficients, corrected item total correlation coefficients, and the test-retest method. The reliability analyzes of SMCS were performed in three different samples (EFA, CFA, and criterion validity). Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficients of SMCS were determined to be .79 in the EFA sample, .84 in the CFA sample, and .82 in the criterion validity sample. Correlated item total correlation coefficients of the SMCS were between .26 and .72 in the EFA sample, .49 and .77 in the CFA sample, and .47 to .73 in the criterion validity sample. The consistency of the SMCS against time spent using social media was examined and performed 3 weeks apart. The test-retest reliability coefficient of the SMCS was found to be .83.

Discussion

Using social media can immediately bring together individuals living in different geographical locations. Furthermore, using social media can bring many benefits such as (among other things) knowledge acquisition, communication, fun, gaming, shopping, and doing research. In these aspects, using social media is an important mass communication tool that makes life easier for the majority of individuals. However, when social media is abused, it may start to cause harm for a minority of individuals. Extreme abuse of using social media has been conceptualized by some scholars as being an addiction (Andreassen et al. 2017), a disorder (Savci and Aysan 2018), problematic (Meena et al. 2012), compulsive (De Cock et al. 2014), and/or pathological (Holmgren and Coyne 2017). One of the overlaps between these concepts is the desire and craving to use social media. Consequently, studies examining social media craving are important. The aim of the present study was to develop the Social Media Craving Scale (SMCS) by adapting the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS).

The reliability and validity of the SMCS were examined via robust psychometric testing. Firstly, the factor structure of the SMCS was investigated with EFA. The factor structure determined as a result of EFA was then tested with CFA (in different samples). Finally, the criterion validity of the SMCS was examined. The criterion validity of the SMCS was assessed with SMDS, BSCS (self-discipline, impulsiveness), daily social media use duration, social media usage history, frequency of checking social media accounts during the day, number of social media accounts, and number of daily shares on social media. The reliability of SMCS was analyzed using Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficients, corrected item total correlation coefficients, and the test-retest method.

As a result of EFA, the SMCS was found to be single-factor (i.e., unidimensional). This single-factor structure explained approximately half of the total variance. The explained variance was sufficient for unidimensional scales (Buyukozturk 2010; Cokluk et al. 2012). The unidimensional structure of SMCS was tested in two different samples with CFA. As a result of CFA, SMCS models were found to have acceptable fit values. The fit indices in Table 2 demonstrate acceptable values. In the EFA and the CFA samples, factor loading values related to items having acceptable values. Factor loading values are accepted as > .30 (Kline 1994) or > .32 (Tabachnick and Fidell 2013). The criterion validity of the SMCS was also examined. The criterion validity of the SMCS was assessed with measures of social media disorder, self-discipline, impulsiveness, daily social media use duration, social media usage history, frequency of checking social media accounts during the day, number of social media accounts, and number of daily shares on social media. Analysis demonstrated that the SMCS was associated with all these variables in the expected direction. In the social sciences, in order to evaluate a scale as reliable, a test-retest coefficient and internal consistency coefficient should be .70 and above (Cokluk et al. 2012). The test-retest reliability coefficient calculated in this study had an acceptable value. The Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient calculated in three different samples all had acceptable values. Finally, the corrected item total coefficients indicated that SMCS was a reliable scale. The corrected item total coefficients calculated in three different samples had acceptable values. Consequently, the findings of the present study indicate that the SMCS is a valid and reliable scale for assessing social media craving.

Although the SMCS has strong validity and reliability, the present study had some limitations. The validity and reliability analyses of SMCS were performed among a “normal” (i.e., non-clinical) population. Therefore, in future studies, the validity and reliability of the SMCS should be examined in clinical samples of those with problematic social media use. The SMCS is a self-report scale, and the criterion validity of the SMCS was also assessed with self-report scales. Self-report data may not provide completely objective data and is subject to well-known biases such as memory recall and social desirability. However, the collection of this type of data is unavoidable in the testing of psychometric instruments. In the present study, an appropriate convenience sampling method was used. However, random sampling method may increase the measurement power of the SMCS. Finally, the SMCS was developed and tested using university students. In future studies, the validity and reliability of the SMCS should be examined on other populations (e.g., non-university adolescents, adult samples, clinical samples). This is likely extend the scope of use of the SMCS.

References

Ağyar-Bakır, B., & Uzun, B. (2018). Developing the social media addiction scale: validity and reliability studies. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 5(3), 507–525. https://doi.org/10.15805/addicta.2018.5.3.0046.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Andreassen, C., & Pallesen, S. (2014). Social network site addiction – an overview. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4053–4061. https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990616.

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.pr0.110.2.501-517.

Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006.

Blackwell, D., Leaman, C., Tramposch, R., Osborne, C., & Liss, M. (2017). Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039.

Buyukozturk, Ş. (2010). Sosyal bilimler için veri analizi el kitabı [Manual of data analysis for social sciences]. Ankara: Pegem Publishing.

Chodkiewicz, J., Ziółkowski, M., Czarnecki, D., Gąsior, K., Juczyński, A., Biedrzycka, B., & Nowakowska-Domagała, K. (2018). Validation of the polish version of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS). Psychiatria Polska, 52(2), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.12740/pp/onlinefirst/40548.

Cokluk, Ö., Sekercioglu, G., & Buyukozturk, Ş. (2012). Sosyal bilimler için çok değişkenli istatistik: SPSS ve Lisrel uygulamalari [Multivariate SPSS and LISREL applications for social sciences]. Ankara: Pegem Publishing.

De Cock, R., Vangeel, J., Klein, A., Minotte, P., Rosas, O., & Meerkerk, G.-J. (2014). Compulsive use of social networking sites in Belgium: prevalence, profile, and the role of attitude toward work and school. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(3), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0029.

Dong, G., Wang, L., Du, X., & Potenza, M. N. (2017). Gaming increases craving to gaming-related stimuli in individuals with internet gaming disorder. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 2(5), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.01.002.

Elphinston, R. A., & Noller, P. (2011). Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14(11), 631–635. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0318.

Evren, C., Flannery, B., Çelik, R., Durkaya, M., & Dalbudak, E. (2008). Reliability and validity of Turkish version the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS) in male alcohol dependent inpatients. Journal of Dependence, 9(3), 128–134.

Flannery, B. A., Volpicelli, J. R., & Pettinati, H. M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 23(8), 1289–1295. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000374-199908000-00001.

Grant, J. E., Potenza, M. N., Weinstein, A., & Gorelick, D. A. (2010). Introduction to behavioral addictions. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.491884.

Griffiths, M. (1996). Behavioural addiction: an issue for everybody? Employee Counselling Today, 8(3), 1925. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665629610116872.

Griffiths, M. (2005). A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Social networking addiction: Emerging themes and issues. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy, 4, e118. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.1000e118.

Griffiths, M. D., & Szabo, A. (2014). Is excessive online usage a function of medium or activity? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(1), 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.2.2013.016.

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addiction: an overview of preliminary findings. In K. P. Rosenberg & L. C. Feder (Eds.), Behavioral addictions: criteria, evidence, and treatment (pp. 119–141). New York: Elsevier.

Guedes, E., Sancassiani, F., Carta, M. G., Campos, C., Machado, S., King, A. L. S., & Nardi, A. E. (2016). Internet addiction and excessive social networks use: what about Facebook? Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 12(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901612010043.

He, Q., Turel, O., & Bechara, A. (2017). Brain anatomy alterations associated with social networking site (SNS) addiction. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 45064. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45064.

He, Q., Turel, O., & Bechara, A. (2018). Association of excessive social media use with abnormal white matter integrity of the corpus callosum. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 278, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.06.008.

Holmgren, H. G., & Coyne, S. M. (2017). Can’t stop scrolling!: pathological use of social networking sites in emerging adulthood. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(5), 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1294164.

Hormes, J. M., Kearns, B., & Timko, C. A. (2014). Craving Facebook? Behavioral addiction to online social networking and its association with emotion regulation deficits. Addiction, 109(12), 2079–2088. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12713.

Huang, H. (2013). Social media addiction, academic performance, and social capital. In H. Huang (Ed.), Social media generation in urban China a study of social media use and addiction among adolescents (pp. 103–112). Berlin: Springer.

Huang, H., & Leung, L. (2009). Instant messaging addiction among teenagers in China: shyness, alienation, and academic performance decrement. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(6), 675–679. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2009.0060.

Karadağ, E., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., Erzen, E., Duru, P., Bostan, N., Şahin, B. M., et al. (2015). Determinants of phubbing, which is the sum of many virtual addictions: a structural equation model. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(2), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.005.

Kemp, S. (2018). Digital in 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018, from: https://wearesocial.com/blog/2018/01/global-digital-report-2018.

Kim, M. J., Kim, S. G., Kim, H. J., Kim, H. C., Park, J. H., Park, K. S., Lee, D. K., Byun, W. T., & Kim, C. M. (2008). A study of the reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale for alcohol-dependent patients. Psychiatry Investigation, 5(3), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2008.5.3.175.

Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Instagram addiction and the big five of personality: the mediating role of self-liking. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(1), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.15.

Kline, P. (1994). An easy guide to factor analysis. London: Routledge.

Koc, M., & Gulyagci, S. (2013). Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: the role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16(4), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0249.

Kraus, S., & Rosenberg, H. (2014). The Pornography Craving Questionnaire: psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0229-3.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011a). Online social networking and addiction – a review of the psychological literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(9), 3528–3552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8093528.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011b). Excessive online social networking: can adolescents become addicted to Facebook? Education and Health, 29(4), 68–71.

Levenson, J. C., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., & Primack, B. A. (2016). The association between social media use and sleep disturbance among young adults. Preventive Medicine, 85, 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.01.001.

Meena, P., Mittal, P., & Solanki, R. (2012). Problematic use of social networking sites among urban school going teenagers. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 21(2), 94–97. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.119589.

Nebioglu, M., Konuk, N., Akbaba, S., & Eroglu, Y. (2012). The investigation of validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the brief self-control scale. Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22(4), 340–351.

Pantic, I., Damjanovic, A., Todorovic, J., Topalovic, D., Bojovic-Jovic, D., Ristic, S., & Pantic, S. (2012). Association between online social networking and depression in high school students: Behavioral physiology viewpoint. Psychiatria Danubina, 24(1), 90–93.

Pawlikowski, M., Altstötter-Gleich, C., & Brand, M. (2013). Validation and psychometric properties of a short version of Young’s Internet Addiction Test. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1212–1223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.014.

Pérez Gálvez, B., De Juan-Gutiérrez Maroto, J., García Fernández, L., Cabot Ivorra, N., & De Vicente Manzanaro, M. P. (2016). Validación de tres instrumentos de evaluación del craving al alcohol en una muestra española: PACS, OCDS-5 y ACQ-SF-R. Health and Addictions/Salud y Drogas, 16(2), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.21134/haaj.v16i2.260.

Pontes, H. M. (2017). Investigating the differential effects of social networking site addiction and internet gaming disorder on psychological health. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.075.

Rogers, P. J., & Smit, H. J. (2000). Food craving and food “addiction”. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 66(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00197-0.

Ryan, T., & Xenos, S. (2011). Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the big five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(5), 1658–1664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.02.004.

Savci, M. (2017). Relationships among relational social connectedness, internet addiction, peer relations, social anxiety and social intelligence levels of adolescents. Doctoral thesis, Dokuz Eylul University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Izmır.

Savci, M., & Aysan, F. (2016). Relationship between impulsivity, social media usage and loneliness. Educational Process: International Journal, 5(2), 106–115.

Savci, M., & Aysan, F. (2017). Technological addictions and social connectedness: predictor effect of internet addiction, social media addiction, digital game addiction and smartphone addiction on social connectedness. Dusunen Adam: The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 30(3), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.5350/dajpn2017300304.

Savci, M., & Aysan, F. (2018). #Interpersonal competence, loneliness, fear of negative evaluation, and reward and punishment as predictors of social media addiction and their accuracy in classifying adolescent social media users and non-users. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 5(3), 431–471. https://doi.org/10.15805/addicta.2018.5.3.0032.

Savci, M., Ercengiz, M., & Aysan, F. (2018). Turkish adaptation of social media disorder scale in adolescents. Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 55(3), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2017.19285.

Shin, Y.-B., Kim, J.-J., Kim, M.-K., Kyeong, S., Jung, Y. H., Eom, H., & Kim, E. (2018). Development of an effective virtual environment in eliciting craving in adolescents and young adults with internet gaming disorder. PLoS One, 13(4), e0195677. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195677.

Statham, D. J., Connor, J. P., Kavanagh, D. J., Feeney, G. F. X., Young, R. M. D., May, J., & Andrade, J. (2011). Measuring alcohol craving: development of the alcohol craving experience questionnaire. Addiction, 106(7), 1230–1238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03442.x.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). USA: Pearson Education.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x.

Turel, O., & Bechara, A. (2016). Social networking site use while driving: ADHD and the mediating roles of stress, self-esteem and craving. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 455. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00455.

Turkish Statistical Institute. (2017). Household information technology usage research (In Turkish hanehalki bilişim teknolojileri kullanım araştırması). Retrieved 19 September 2018, from: http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=24862

Van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Lemmens, J. S., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). The social media disorder scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038.

Wegmann, E., Stodt, B., & Brand, M. (2015). Addictive use of social networking sites can be explained by the interaction of internet use expectancies, internet literacy, and psychopathological symptoms. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.021.

Woods, H. C., & Scott, H. (2016). #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence, 51, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008.

World Health Organisation. (1993). ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. Switzerland: World Health Organisation.

Yıldız-Durak, H. (2018). What would you do without your smartphone? Adolescents’ social media usage, locus of control, and loneliness as a predictor of nomophobia. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 5(3), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.15805/addicta.2018.5.2.0025.

Young, M. M., & Wohl, M. J. A. (2009). The gambling craving scale: psychometric validation and behavioral outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(3), 512–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015043.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Committee Approval

Ethics committee approval was obtained for this study. The authors report that the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Informed Consent

The informed consent form was read by the researcher in the classroom environment.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest

Peter J. Rogers has received grants to support research on caffeine from GlaxoSmithKline. Csilla Ágoston, Róbert Urbán, Orsolya Király, Mark D. Griffiths, and Zsolt Demetrovics declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of University’s Research Ethics Board and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sosyal Medya Aşerme Ölçeği (İOOAÖ)

Bu araştırma sosyal medya kullanma isteğinizi değerlendirmek amacıyla gerçekleştirilmektedir. Lütfen aşağıda verilen soruları okuyarak size uygun olan seçeneği belirtiniz. Lütfen her maddeyi dikkatlice okuyun ve son bir haftayı dikkate alarak, sosyal medya aşermenizi (sosyal medya kullanma isteğinizi) en iyi tanımlayan seçeneği işaretleyin.

1. Son bir haftayı dikkate aldığınızda, sosyal medya kullanmak ile ilgili ya da sosyal medya kullanmanın sizi ne kadar iyi hissettireceği ile ilgili ne sıklıkta düşündünüz? | |

⓪ Hiç (geçtiğimiz hafta içinde 0 defa) ① Nadiren (geçtiğimiz hafta içinde 1-2 defa) ② Ara sıra (geçtiğimiz hafta içinde 3-4 defa) ③ Bazen (geçtiğimiz hafta içinde 5 ila 10 defa veya günde 1-2 defa) ④ Sıklıkla (geçtiğimiz hafta içinde 11-20 defa veya günde 2-3 defa) ⑤ Çoğu zaman (geçtiğimiz hafta içinde 20-40 defa veya günde 3-6 defa) ⑥ Neredeyse her zaman (geçtiğimiz hafta içinde 40 defadan fazla veya günde 6 defadan fazla) | |

2. Son bir haftayı dikkate aldığınızda, en şiddetli noktasında, sosyal medya aşermeniz ne kadar güçlüydü? | |

⓪ Hiç istek yoktu ① Önemsenmeyecek düzeyde, yani çok hafif istek ② Hafif istek ③ Orta düzeyde istek ④ Güçlü istek, fakat kolaylıkla kontrol edildi ⑤ Güçlü istek ve kontrol edilmesi zor ⑥ Güçlü istek ve kontrol edilemez | |

3. Son bir haftayı dikkate aldığınızda, sosyal medya kullanmak ile ilgili ya da sosyal medya kullanmanın sizi ne kadar iyi hissettireceği ile ilgili düşünmeye ne kadar zaman harcadınız? | |

⓪ Hiç ① 20 dakikadan az ② 21-45 dakika ③ 46-90 dakika ④ 90 dakika -3 saat ⑤ 3-6 saat arası ⑥ 6 saatten daha fazla | |

4. Son bir haftayı dikkate aldığınızda, eğer sosyal medya kullanma imkânınız olduğunu bilseydiniz sosyal medya kullanmaya direnmek ne kadar zor olurdu? | |

⓪ Hiç zor olmazdı ① Çok hafif zor ② Hafif zor ③ Orta zorlukta ④ Çok zor ⑤ Aşırı zor ⑥ Karşı koyamazdım | |

5. Önceki sorulara verdiğiniz cevapları aklınızda tutarak, lütfen son bir hafta için ortalama sosyal medya aşermenizi değerlendirin. ⓪ Hiç kullanma düşüncem olmadı ve hiç kullanma isteğim olmadı. ① Nadiren kullanmayla ilgili düşündüm ve nadiren kullanma isteğim oldu. ② Ara sıra kullanmayla ilgili düşündüm ve ara sıra kullanma isteğim oldu. ③ Bazen kullanmayla ilgili düşündüm ve bazen kullanma isteğim oldu. ④ Sıklıkla kullanmayla ilgili düşündüm ve sıklıkla kullanma isteğim oldu. ⑤ Çoğu zaman kullanmayla ilgili düşündüm ve çoğu zaman kullanma isteğim oldu. ⑥ Neredeyse her zaman kullanmayla ilgili düşündüm ve neredeyse her zaman kullanma isteğim oldu. |

Appendix 2. Social Media Craving Scale (SMCS)

This research is carried out to evaluate your social media craving (desire for social media use). Please read the following questions and choose the option that suits you. Please, consider the option for each question that best describes your social media craving over the past week.

1. In the past week, how often have you thought about using social media or about how good using social using would make you feel? | |

⓪ Never, that is, 0 times during this period of time. ① Rarely, that is, 1 to 2 times during this period of time. ② Occasionally, that is, 3 to 4 during this period of time. ③ Sometimes, that is, 5 to 10 times during this period or 1 to 2 times a day. ④ Often, that is, 11 to 20 times during this period or 2 to three times a day. ⑤ Most of the time, that is, 20 to 40 during this period or 3 to 6 times a day. ⑥ Nearly all of the time, that is, more than 40 times during this period or more than 6 times a day. | |

2. In the past week at its most severe point, how strong was your social media craving? | |

⓪ None at all. ① Slight, that is a very mild urge. ② Mild urge. ③ Moderate urge. ④ Strong urge, but easily controlled. ⑤ Strong urge and difficult to control. ⑥ Strong urge and uncontrollable. | |

3. In the past week, how much time have you spent thinking about using social media or about how good using social media would make you feel? | |

⓪ None at all. ① Less than 20 min. ② 21–45 min. ③ 46–90 min. ④ 90 min-3 h. ⑤ Between 3 to 6 h. ⑥ More than 6 h. | |

4. In the past week, how difficult would it have been to resist using social media if you knew you had the opportunity to engage in using social media? | |

⓪ Not difficult at all. ① Very mildly difficult. ② Mildly difficult. ③ Moderately difficult. ④ Very difficult. ⑤ Extremely difficult. ⑥ Would not be able to resist. | |

5. Keeping in mind your responses to the previous questions, please rate your overall average social media craving during the past week. ⓪ Never thought about social media using and never had the urge to social media using. ① Rarely thought about social media using and rarely had the urge to social media using. ② Occasionally thought about social media using and occasionally had the urge to social media using. ③ Sometimes thought about social media using and sometimes had the urge to social media using. ④ Often thought about social media using and often had the urge to social media using. ⑤ Thought about social media using most of the time and had the urge to social media using most of the time. ⑥ Thought about social media using nearly all of the time and had the urge to social media using nearly all of the time. |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Savci, M., Griffiths, M.D. The Development of the Turkish Social Media Craving Scale (SMCS): a Validation Study. Int J Ment Health Addiction 19, 359–373 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00062-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00062-9