Abstract

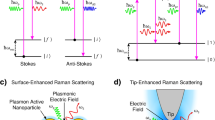

We present a new method enabling simultaneous synthesis and deposition of gold micro-flowers (AuMFs) on solid substrates in a one-pot process that uses two reagents, auric acid and hydroxylamine hydrochloride, in aqueous reaction mixture. The AuMFs deposited onto the substrate form mechanically stable gold layer of expanded nanostructured surface. The morphology of the AuMFs depends on and can be controlled by the composition of the reaction solution as well as by the reaction time. The nanostructured metallic layers obtained with our method are employed as efficient platforms for chemical and biological sensing based on surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). SERS spectra recorded by such platforms for p-mercaptobenzoic acid and phage lambda exhibit enhancement factors above 106 and excellent reproducibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Noble metal nano- and microstructures of nonspherical shapes have received much attention in recent years [1–5]. Their morphological forms—including flower-, rod-, wire-, and plate-like structures—exhibit unusual optical [6], electronic [7], and catalytic [8, 9] properties. Very promising area of applications of gold nano- and microflowers is surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). Surfaces modified with such flower-like structures have proved [10–14] to provide large SERS enhancement factors. Known methods [1, 6, 8–22] of synthesis of gold microflowers (AuMFs) require fairly elaborate techniques. With these methods, AuMFs are typically synthesized in reaction solutions containing gold salts, reducing agents, buffers, and additional reagents that strongly affect both size and the morphology of the resulting structures. For instance, reagents like polianiline [1], chitosan [15, 16], surfactants [17, 18], or DNA [19] have been utilized to obtain gold particles of ragged, flower-like shapes. Similar structures have also recently been fabricated mechanically by a centrifuging process [20]. Synthesis of rough flower-like complexes directly on surfaces is usually carried out electrochemically via electrodeposition [10] or seed-mediated growth approach [21]. In this study, we present a novel facile method enabling simultaneous synthesis and deposition of the AuMFs on hydrophilic solid substrates. The method developed is a one-pot process using only two simple reagents in aqueous reaction mixture. We demonstrate that substrates covered with a layer of the AuMFs using our technique can be employed as efficient, highly reproducible SERS platforms, providing the enhancement factor of the order of 106.

Experimental

Chemicals

Auric acid (HAuCl4) and hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH2OH·HCl) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The reagents were all analytical grade and used without additional purification. Concentrated sulfuric acid, hydrochloride, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric acid were purchased from Chempur. We employed as solvents acetone and methanol from Chempur and deionized water (15 MΩ). The glass microscope slides were obtained from Roth. The silicon-polished wafers were obtained from Cemat Silicon.

Preparation of the Reaction Mixture

To prepare the reaction mixture, solution of auric acid was added dropwise while stirring to an aqueous solution of hydroxylamine hydrochloride. The resulting reaction mixture was fully characterized by the HAuCl4/NH2OH molar ratio and the concentration of hydroxylamine. In this paper, the mixture concentration is given relative to the reference solution, c1, containing 0.5 mM of NH2OH. For example, to obtain the c1 (3:8) reaction mixture containing 3:8 HAuCl4/NH2OH molar ratio, one volume of 0.8 mM NH2OH with 0.6 volume of 0.5 mM HAuCl4 were mixed. Mixtures diluted ten times are marked—irrespectively of their HAuCl4/NH2OH molar ratio—as c0.1. Similarly, mixtures with ten times higher concentration of hydroxylamine are marked as c10, etc.

Covering Substrates with AuMFs

With our method, the flower-like structures were produced by reduction of gold Au3+ ions by hydroxylamine. The reaction mixture—aqueous solution of auric acid and hydroxylamine hydrochloride—was prepared as described previously. The reaction proceeded according to the following equation: 3 NH2OH·HCl + 4 HAuCl4 + 3 H2O = 3 HNO2 + 4 Au0 + 19 HCl. In the process, clusters of metallic gold (AuMFs) were formed in the bulk solution and simultaneously adsorbed on a substrate plate to form thick, permanent layer of sediment. Our experimental procedure is outlined schematically in Fig. 1.

Covering substrate with AuMFs. a Aqueous solutions of HAuCl4 and NH2OH·HCl are mixed. b Substrate plate is placed horizontally in a vial containing the reaction mixture. Metallic gold is formed in the bulk solution. c Microflowers are formed and adsorbed on the plate. d After the reaction is completed, the plate is taken out, washed, and dried. The resulting porous gold coating is mechanically stable and can be further processed without additional cleaning. e Substrate covered with as-prepared gold layer. Photo image of a silicon plate covered with AuMFs (applied as the SERS platform). The width of the plate is 10 mm

Before use, the substrate plate was cleaned by sonication first in water and then in acetone. Next, the plate was immersed in a freshly prepared piranha solution (3:1 H2SO4:30% H2O2) for 3 h. Finally, the plate was richly rinsed with deionized water and then with methanol. The reaction mixture was prepared according to the procedure described previously in this section. As soon as the reagents were stirred, the dried slides were placed horizontally in a vial containing this mixture for 1 h. Then, the plate was carefully washed subsequently with water and with methanol, and dried.

Fabrication of SERS Platform

To obtain the SERS platform, we followed the general covering procedure outlined in Fig. 1. Silicon plates were applied as substrates. Before used, the plate was roughened by scratching it with sandpaper (grit size 500). The roughened plate, cleaned as described above, was placed horizontally at the bottom of a vial containing a c50 (3:8) fresh reaction mixture [c50 (3:8) mixture consists one volume of 40 mM NH2OH with 0.6 volume of 25 mM HAuCl4]. The height of the solution column above the plate was about 10 mm. After 24 h, the plate with deposited AuMFs porous film was carefully washed subsequently with deionized water and with methanol and then dried in air. Finally, the plate was—without additional cleaning—immersed in the analyte solution for 6–48 h and dried in air before the SERS measurements.

Instrumentation

Surfaces covered with AuMFs were analyzed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with Neon 40-Auriga Carl Zeiss apparatus. The absorption spectra were recorded on Ocean Optics USB 2000+ spectrophotometer in the spectral range 300–800 nm in quartz micro cuvette (10 mm of path length). The sample was illuminated with UV-VIS-NIR LIGHTSOURCE DH-2000, Ocean Optics. The absorption spectra were recorded starting from 35th second of the reaction. SERS measurements were performed using the Renishaw InVia Raman system equipped with a He-Ne laser emitting a 632.5 nm line used as the excitation source. The light from the laser was passed through a line filter, and focused on a sample mounted on an X-Y-Z translation stage with a ×50 microscope objective. The Raman-scattered light was collected by the same objective through a holographic notch filter to block out Rayleigh scattering. A 1,800 groove/mm grating was used to provide spectral resolution of 1 cm−1. The Raman scattering signal was detected by the 1,024 × 256 pixel RenCam CCD detector. The SERS signal was collected for a dried sample on the SERS substrate. The SERS spectra were acquired using 150 s integration time and processed with the Renishaw software WiRE 3.2.

Results and Discussion

Effect of Composition of the Reaction Mixture on the Morphology of AuMFs

The reaction mixture was fully characterized by the concentration of hydroxylamine and the HAuCl4/NH2OH molar ratio. To investigate the effect of the molar ratio of reagents on the AuMF morphology, we employed nine c1 reaction mixtures of fixed concentration of hydroxylamine (0.5 mM) and different molar ratios. The molar ratios ranged from 1:8 to 9:8. In each case, silicon plate was immersed for 24 h in the reaction mixture. The morphology of the AuMFs deposited on the plate was analyzed using SEM. We found that, for each molar ratio used, only flower-shaped microstructures were present. The AuMFs formed had sizes in the range of 0.8–2.5 μm and were randomly distributed on the substrate. The analysis of the SEM images revealed that for higher contents of hydroxylamine, for the ratios from 1:8 to 5:8, the AuMFs had a hedgehog-like structure consisting of a number of small "petals" (Fig. 2a and b). AuMFs obtained for lower contents of hydroxylamine, from 7:8 to 9:8, exhibited less expanded morphology, with a fewer number of petals (Fig. 2c, d). To check the effect of the concentration of reagents on the morphology of the AuMFs, we investigated mixture concentrations in the range from c0.05 to c50 for each of the molar ratios used. We found that the reagent concentration does not have any noticeable effect on the AuMF morphology. However, for the concentrations lower than c0.4 amorphous gold particles were formed, and the flower-like structures were not observed.

Our experimental results suggest that the flower-like particles are not observed for the concentrations lower than c0.4 because of insufficient amount of gold ions in the reaction mixture. As we found from the analysis of the SEM images, the average number of particles created during the reaction was similar for the concentrations from the range c0.05–c1. However, the average size of the particles observed for the low concentrations was significantly smaller than that observed for the concentrations greater than c0.4. This observation indicates that in the low concentration reaction mixtures there is not enough matter for the nuclei to grow and develop properly shaped “petals”.

Effect of Reaction Time on the Morphology of AuMFs

To investigate the effect of the immersion time on the AuMF morphology, silicon plates were dipped into the reaction solution c1 (3:8) for short (2–10 min) and long times (from 30 min up to 7 days). Analysis of the SEM images revealed that the AuMFs obtained for the short immersion times—independently of the composition of the reaction mixture—consisted of very thin, plate-like petals of polygonal shapes. For the immersion time of 30 min, the AuMFs were much smoother and their surface was composed of rounded petals. Similar round-edged morphology of the AuMFs was also observed for longer immersion times. The shapes of the petals observed for the longest immersion time (7 days) did not differ much from those observed for the immersion time of 30 min. Examples of the sharp- and round-edged AuMF are shown in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. A plausible explanation for the edge smoothing is a thermodynamically driven redistribution of Au atoms within the AuMF. In this process, the atoms migrate away from energetically unfavorable places, like sharp edges or tips, to decrease average curvature of the surface. This atom redistribution process is slow compared to the autocatalytic growth of the AuMFs. Most likely, the edge smoothing continues during the whole immersion time but its effects are most visible in the late stages of the AuMF growth process, when the reagents are consumed and the growth of AuMFs is terminated.

Kinetics of the AuMF Formation

To investigate the kinetics of the reaction, we monitored changes of the absorbance of the unconsumed Au3+ ions in the solution using UV-Vis spectroscopy. The absorbance spectrum of Au3+ ions displayed a maximum at λ = 230 nm. In our analysis, we assumed that—for the concentrations of the auric acid used—the Beer’s law holds and the absorbance is proportional to the concentration of the Au3+ ions. Also, for the sake of simplicity, in the fitting procedure (vide infra) we set the proportionality constant equal to unity and treated the absorbance at λ 230 as the Au3+ concentration. The time dependence of the value of the absorbance at λ 230 is plotted in Fig. 4a.

a Changes of the absorbance due to the unconsumed Au3+ ions during the formation of AuMFs in the c1 (3:8) reaction mixture. The red line is the fit of the two-step model (see the text) to the experimental data. Two SEM images show examples of the sharp-edged AuMF created in the autocatalytic growth stage (5–12 min), and the round-edged AuMF observed for longer immersion times. b Cartoon representation of the three stages of the AuMF formation process: nucleation, autocatalytic growth, and the edge smoothing

We employed a minimalistic reaction model that accounts for the kinetic data obtained. According to this model, the reaction proceeds in two stages, which are nucleation and autocatalytic growth of the metallic clusters. From the plot, it follows that the first step of the reaction occurs in the first 5 min. The second stage takes place roughly between fifth and twelfth minute of reaction. In general, the reaction time of the chemical reduction of gold ions observed in our method is similar to that reported by other researchers for the seedless methods [8, 14–18].

This two-step model follows from the fact that hydroxylamine is thermodynamically capable to reduce Au3+ ions directly to metallic gold [23], but this reaction is dramatically accelerated by the presence of gold surfaces [24, 25]. For this reason, production of new nuclei is suppressed in a solution that contains colloidal gold nanoclusters [25]. One therefore expects that the formation of the AuMFs occurs in the following two stages. (1) Initially, the Au3+ ions are reduced in the bulk solution to form nuclei. Although the nuclei created grow autocatalytically, at this stage, the consumption of the gold ions is due mainly to the nucleation processes. (2) As the concentration of the nuclei (seeds) increases, the nucleation process is gradually suppressed and replaced by the autocatalytic (surface catalyzed) reduction of Au3+. The stages are described below.

Nucleation

Reduction of the Au3+ ions directly to metallic gold is described by the following one-step mechanism:

where, A stands for Au3+, B is metallic gold, and k 1 is the effective rate of the reduction of Au3+ ions (i.e., the nucleation process). The reaction described by Eq. 1 yields exponential decay of the concentration of Au3+ ions, [A](t),

where, [A]0 is the initial concentration of Au3+ ions in the reaction solution.

Autocatalytic Growth

We assume that the surface catalyzed reduction of Au3+ occurs according to the scheme

where, k 2 is the rate of the reduction of Au3+ ions on gold surfaces. Reaction 3 gives the following time dependence of the concentration of the unconsumed Au3+ ions:

Here [A]1 and [B]1 denote, respectively, the concentration of the Au3+ ions and surface atoms of the growing clusters (seeds) present at the beginning of the autocatalytic growth stage. The quantities [A]0 and [A]1 are linked by the relation [A]1 = [A]0exp(−k 1 t n), where t n is the duration of the nucleation stage.

We fitted the functions given by Eqs. 2 and 4 to the absorbance data using t n, [A]0, k 1, α, β, and k 2 as the fitting parameters. The fitting procedure yielded t n = 5.0 ± 0.5 min, [A]0 = 1.040 ± 0.002, and k 1 = 0.0550 ± 0.0006 for the nucleation reaction and α = 0.853 ± 0.008, β = 0.0024 ± 0.0004, and k 2 = 0.85 ± 0.02 for the autocatalytic reaction. The resulting kinetic curve is plotted in Fig. 4a. In our attempts to model the formation of the AuMFs, we considered also two-step growth reaction that comprises both nucleation and the autocatalytic growth (Eqs. 1 and 3) that is referred to as the Finke–Watzky (FW) kinetic model [26, 27]. The FW model predicts, however, an S-shaped sigmoidal kinetic curve of the concentration of the unconsumed metal ions that did not fit our experimental data.

For the reaction times less than ~12 min, corresponding to late stages of the nucleation regime and the autocatalytic growth stage, we observed the sharp-edged morphology of the AuMFs. When the reagents were consumed, in late phases of the autocatalytic growth stage, the round-edge morphology was observed. The three stages of the AuMF formation—nucleation followed by the autocatalytic growth, and the edge smooting—are illustrated schematically in Fig. 4b.

SERS Measurements

Our method was successfully applied to fabricate platforms for SERS. To obtain dense layer of the AuMFs, surface of the substrate plate was roughened prior to immersion in the reaction mixture. In our experiments, we employed the c50 (3:8) reaction mixture and the immersion time of 24 h. The roughening of the substrate’s surface provided a "scaffolding" for the adsorbing AuMFs and facilitated fabrication of thick, mechanically durable porous layer. Spatial structure of such nanoroughened layer composed of the AuMFs deposited on silica plate is shown in Fig. 5. Before the SERS measurements, the as-prepared substrate was dipped in solution containing analyte.

For application purposes, SERS substrates are required to have good stability and reproducibility, both within single substrates and between different substrates. Figure 6a shows representative SERS spectra of p-mercaptobenzoic acid (PMBA) adsorbed on the AuMFs deposit that were recorded for three different spots of the sample (marked as B, C, and D). As seen, the position and intensity of all modes corresponding to PMBA (646, 835, 1,080, 1,177, 1,280, and 1,587 cm−1) exhibit remarkably small intrasample variability. The standard deviation of the relative intensity of the 1,080 cm−1 PMBA mode obtained for 100 randomly locations distributed within a single sample surface was less than 15%. Figure 6b shows Raman spectra of PMBA recorded from four different, independently prepared SERS substrates (marked as A, B, C, and D). As can be seen, the SERS signals taken from the four samples are well consistent both in intensity and shape. For example, the intensity of ν8a aromatic ring vibrations mode observed at 1,080 cm−1 varied by less than 20% between different surfaces. The values of the relative standard deviation calculated for our platforms are comparable to those achieved for other methods of fabrication of the SERS platforms. In the available literature [28–31], typical deviation of the SERS intensity across a single substrate is reported to be 3.5–15%. The deviation of the SERS intensity across surfaces prepared in different batches ranges from 10% to 30%.

a SERS spectra of A AuMF deposit on glass, and B, C, D of PMBA recorded from three different spots on the AuMF deposit. b SERS spectra of p-mercaptobenzoic acid recorded from different, independently prepared AuMFs arrays, marked as A, B, C, and D. c SERS spectra recorded for three different concentrations of p-mercaptobenzoic acid molecules in the analyte solution, 10−3, 10−6, and 10−9 M. d SERS spectrum of bacteriophage λ adsorbed onto the AuMF-functionalized substrate, displaying the Raman bands of O-P-O backbone (O-P-O), cytosine (C), guanine (G), adenosine (A), and thymine (T) vibrational modes of DNA

In order to estimate the detection limit for PMBA molecules, the SERS measurements were performed for substrates that were immersed in solutions containing different concentrations of PMBA. The substrates were immersed in each solution for the same period of time (2 h). Three analyte concentrations were applied: 10−3, 10−9, and 10−9 M. The SERS spectra recorded for these concentrations are shown in Fig. 6c. As the amount of the analyte in solution was reduced, the SERS intensity decreased but the Raman band at 1,080 cm−1 was observed even for the lowest PMBA concentration used (marked as A in Fig. 6c).

To demonstrate the applicability of the platforms for biomolecule sensing, we carried out SERS-based detection of the bacteriophage λ. This phage contains double-strainded linear DNA as its genetic material, and infects Escherichia coli. To prepare the SERS platform, 10 μM probe of bacteriophage λ in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 1 M, pH = 6.7) was immobilized on the surface of the AuMF-functionalized plate. The plate was kept in the solution at room temperature for 6 h. Then, excessive bacteriophage was washed with sodium dodecyl sulfate solution in PBS (0.1%, v/v) for 5 min. Figure 6d shows the SERS spectrum of DNA of bacteriophage λ, which clearly displays Raman bands at 883, 1,276, 1,496, 1,558, and 1,670 cm−1 assigned to, respectively, O-P-O backbone, cytosine, guanine, adenosine, and thymine vibrational modes of DNA [32]. This result suggests that SERS platforms fabricated with our method can be successfully applied for identification of biomolecules.

Conclusions

In summary, we developed a novel facile one-pot method for covering solid substrates with stable, thick layer of micrometer-sized AuMF. By changing the composition of the reaction mixture and/or the reaction time, we can easily control the morphology of the AuMFs, that is, the average number and shape of petals of which the AuMFs are composed. Our method is suitable to fabricate platforms for SERS-based chemical and biological sensing. The SERS spectra recorded by platforms for PMBA and bacteriophage λ provided enhancement factors above 106 and exhibited excellent reproducibility both within single substrates and between different substrates. The fact that our platforms allowed detection of Raman bands of the bacteriophage’s DNA is remarkable. It proves that the AuMF-functionalized substrates can be potentially employed for bioanalytical applications. To end, note that due to hazardous substrate minimization, mild reaction conditions, and lack of power consuming processes, our method meets the goals of green chemistry.

References

Sajanlal PR, Sreeprasad TS, Nair AS, Pradeep T (2008) Wires, plates, flowers, needles, and core-shells: diverse nanostructures of gold using polyaniline templates. Langmuir 24:4607–4614

Umar AA, Oyama M (2009) High-yield synthesis of tetrahedral-like gold nanotripods using an aqueous binary mixture of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide and hexamethylenetetramine. Cryst Growth Des 9:1146–1152

Xiao ZL, Han CY, Kwok WK, Wang HW, Welp U, Wang J, Crabtree GW (2004) Tuning the architecture of mesostructures by electrodeposition. J Am Chem Soc 126:2316–2317

Penner RM (2002) Mesoscopic metal particles and wires by electrodeposition. J Phys Chem B 106:3339–3353

Zhang B, Xu P, Xie X, Wei H, Li Z, Mack NH, Han X, Xu H, Wang H-L (2011) Acid-directed synthesis of SERS-active hierarchical assemblies of silver nanostructures. J Mater Chem 21:2495–2501

Sajanlal PR, Pradeep T (2009) Mesoflowers: a new class of highly efficient surface-enhanced Raman active and infrared-absorbing materials. Nano Res 2:306–320

Peto G, Molnar GL, Paszti Z, Geszti O, Beck A, Guczi L (2002) Electronic structure of gold nanoparticles deposited on SiOx/Si. Mater Sci Eng C 19:95–99

Jena BK, Raj CR (2007) Synthesis of flower-like gold nanoparticles and their electrocatalytic activity towards the oxidation of methanol and the reduction of oxygen. Langmuir 23:4064–4070

Li Y, Shi G (2005) Electrochemical growth of two-dimensional gold nanostructures on a thin polypyrrole film modified ITO electrode. J Phys Chem B 109:23787–23793

Kim J-H, Kang T, Yoo SM, Lee SY, Kim B, Choi Y-K (2009) A well-ordered flower-like gold nanostructure for integrated sensors via surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Nanotechnology 20:235302

Xie J, Zhang Q, Lee JY, Wang DIC (2008) The synthesis of SERS-active gold nanoflower tags for in vivo applications. ACS Nano 2:2473–2480

Wang T, Hu X, Dong S (2006) Surfactantless synthesis of multiple shapes of gold nanostructures and their shape-dependent SERS spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B 110:16930–16936

Giannini V, Rodriguez-Oliveros R, Sanchez-Gil JA (2010) Surface plasmon resonances of metallic nanostars/nanoflowers for surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Plasmonics 5:99–104

Jena BK, Raj CR (2008) Seedless, surfactantless room temperature synthesis of single crystalline fluorescent gold nanoflowers with pronounced SERS and electrocatalytic activity. Chem Mater 20:3546–3548

Wang W, Cui H (2008) Chitosan-luminol reduced gold nanoflowers: from one-pot synthesis to morphology-dependent SPR and chemiluminescence sensing. J Phys Chem C 112:10759–10766

Wang W, Yang X, Cui H (2008) Growth mechanism of flowerlike gold nanostructures: surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and resonance Rayleigh scattering (RRS) approaches to growth monitoring. J Phys Chem C 112:16348–16353

Zhong L, Zhai X, Zhu X, Yao P, Liu M (2010) Vesicle-directed generation of gold nanoflowers by gemini amphiphiles and the spacer-controlled morphology and optical property. Langmuir 26:5876–5881

Li H, Yang Y, Wang Y, Li W, Bi L, Wu L (2010) In situ fabrication of flower-like gold nanoparticles in surfactant-polyoxometalate-hybrid spherical assemblies. Chem Commun 46:3750–3752

Wang Z, Zhang J, Ekman JM, Kenis PJA, Lu Y (2010) DNA-mediated control of metal nanoparticle shape: one-pot synthesis and cellular uptake of highly stable and functional gold nanoflowers. Nano Lett 10:1886–1891

Wang L, Wei G, Guo C, Sun L, Sun Y, Song Y, Yang T, Li Z (2008) Photochemical synthesis and self-assembly of gold nanoparticles. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem Eng Aspects 312:148–153

Das AK, Raj CR (2010) Facile growth of flower-like Au nanocrystals and electroanalysis of biomolecules. J Electroanal Chem 638:189–194

Huang X-J, Yarimaga O, Kim J-H, Choi Y-K (2009) Substrate surface roughness-dependent 3-D complex nanoarchitectures of gold particles from directed electrodeposition. J Mater Chem 19:478–483

Bard AJ (1975) Encyclopedia of electrochemistry of the elements, vol 4 and 8. Marcel Dekker, New York

Stremsdoerfer G, Perrot H, Martin JR, Clechet P (1988) Autocatalytic deposition of gold and palladium onto n-GaAs in acidic media. J Electrochem Soc 135:2881–2886

Brown KR, Natan MJ (1998) Hydroxylamine seeding of colloidal Au nanoparticles in solution and on surfaces. Langmuir 14:726–728

Watzky MA, Finke RG (1997) Transition metal nanocluster formation kinetic and mechanistic studies. A new mechanism when hydrogen is the reductant: slow, continuous nucleation and fast autocatalytic surface growth. J Am Chem Soc 119:10382–10400

Finney EE, Finke RG (2009) Fitting and interpreting transition-metal nanocluster formation and other sigmoidal-appearing kinetic data: a more thorough testing of dispersive kinetic vs chemical-mechanism-based equations and treatments for 4-step type kinetic data. Chem Mater 21:4468–4479

Mulvaney SP, He L, Natan MJ, Keating CD (2003) Three-layer substrates for surface-enhanced Raman scattering: preparation and preliminary evaluation. J Raman Spectroscop 34:163–171

Oran JM, Hinde RJ, Hatab NA, Retterer ST, Sepaniak MJ (2008) Nanofabricated periodic arrays of silver elliptical discs as SERS substrates. J Raman Spectroscop 39:1811–1820

Khan MA, Hogan TP, Shanker B (2009) Gold-coated zinc oxide nanowire-based substrate for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J Raman Spectroscop 40:1539–1545

Driskell JD, Shanmukh S, Liu Y, Chaney SB, Tang H-J, Zhao Y-P, Dluhy RA (2008) The use of aligned silver nanorod arrays prepared by oblique angle deposition as surface enhanced Raman scattering substrates. J Phys Chem C 112:895–901

Naumann D (2001) FT-infraredand FT-Raman spectroscopy in biomedical research. Appl Spectrosc Rev 36:239–298

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education as scientific projects (2007–2010) and "Iuventus Plus" (IP2010025970). The research was partially supported by the European Union within European Regional Development Fund, through grant Innovative Economy (POIG.01.01.02-00-008/ 08).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Winkler, K., Kaminska, A., Wojciechowski, T. et al. Gold Micro-Flowers: One-Step Fabrication of Efficient, Highly Reproducible Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Platform. Plasmonics 6, 697–704 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-011-9253-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-011-9253-0