Abstract

This paper considers the role of seafaring as an important aspect of everyday life in the communities of prehistoric Cyprus. The maritime capabilities developed by early seafarers enabled them to explore new lands and seas, tap new marine resources and make use of accessible coastal sites. Over the long term, the core activities of seafaring revolved around the exploitation of marine and coastal resources, the mobility of people and the transport and exchange of goods. On Cyprus, although we lack direct material evidence (e.g. shipwrecks, ship representations) before about 2000 BC, there is no question that beginning at least by the eleventh millennium Cal BC (Late Epipalaeolithic), early seafarers sailed between the nearby mainland and Cyprus, in all likelihood several times per year. In the long stretch of time—some 4000 years—between the Late Aceramic Neolithic and the onset of the Late Chalcolithic (ca. 6800–2700 Cal BC), most archaeologists passively accept the notion that the inhabitants of Cyprus turned their backs to the sea. In contrast, this study entertains the likelihood that Cyprus was never truly isolated from the sea, and considers maritime-related materials and practices during each era from the eleventh to the early second millennium Cal BC. In concluding, I present a broader picture of everything from rural anchorages to those invisible maritime behaviours that may help us better to understand seafaring as an everyday practice on Cyprus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In different time periods and to varying extents, seafaring and the exploitation of marine and coastal resources formed key aspects of everyday life in the prehistoric communities of Cyprus. Of course, there may be a kernel of truth in James R.B. Stewart’s (1962:290) caustic comment: ‘The Cypriote has never been a great sea-farer … nor has he been a keen fisherman, until the coming of dynamite’. Over the past 60 years, however, our views about (and our interest in) seafaring and seafarers—about maritimity in general—have changed rather dramatically, and in this study I seek to present a ‘maritime narrative’ about prehistoric Cyprus, one represented mainly in the terrestrial archaeological record—the ‘quasi objects’ of a maritime cultural landscape (Tuddenham 2010:11). Like Westerdahl (2007:191), however, I eschew making a hard distinction between the maritime and the terrestrial because ‘The human perspective, after all, always consists of both sea and land’.

This narrative involves very entangled histories, entangled not just in terms of archaeological discoveries themselves and the individual artefacts that result from fieldwork, but also with respect to the broader interpretations we seek to present on the basis of these sites, contexts and artefacts. If we look at more recent periods, e.g. at the discovery and excavation of the late Classical shipwreck at Mazotos (Fig. 1), it is clear that others also become entangled in these narratives, from fishermen and the diving community, to those who conserve antiquities, to the academic, funding and other institutions involved (Demesticha 2018:67–70; see also Demetriou 2016). Moreover, as Frankel (2019:65) recently commented: ‘… while past peoples left residues behind, it is archaeologists who create and structure the archaeological record, finding and defining the evidence … We also bring to this evidence our current understandings, perceptions and concerns which influence what we identify as significant and choose to write about. We readily—perhaps deceptively easily—envisage life in villages, towns and cities …’—and, we should add, ‘on the sea’.

Whereas modern historians and sociocultural anthropologists bear witness to contemporary events and the processes of everyday life, these same events and processes are seldom immediately evident in the prehistoric archaeological record. Not only do some of these social processes occur over centuries or even millennia, they may also engage data sets that stem from vastly different landmasses (e.g. Europe and Asia in the case of ‘Neolithisation’ processes—Parkinson 2017:278) or, as in our case, from an island of some 9000 sq kms as well as the nearby Levantine and Anatolian coasts. Moreover, as Anderson (2010:12) argued, seafaring was intimately connected with terrestrial phenomena like Neolithisation or urbanisation, processes that tend to dominate archaeological thinking about the Holocene.

What follows, then, should probably be regarded as a ‘deceptively easy’, terrestrially based narrative about the role of seafaring and seafarers on prehistoric Cyprus. Based on such evidence as can be marshalled at this time, we may suggest that prehistoric seafaring extended peoples’ habitats and gave them access to resources that lay near and beyond the shore. By the Late Epipalaeolithic and continuing into the Early Aceramic Neolithic (EAN) (see Table 1 for terminology and dates), seafaring must have increased the range and links of fisher-foragers and, with the passage of time, it facilitated the movement of people and certain resources in demand; ultimately, by the Bronze Age and later, it paved the way for merchants and colonists to operate on a much greater scale, facilitating the bulk transport of goods and the expansion of trade, and enabling the establishment of maritime states and kingdoms.

The core activities of seafaring thus revolved around the exploitation of marine and coastal resources, the mobility (if not innate curiosity) of people and the transport and exchange of goods. On Cyprus, before the Middle Bronze Age (i.e. after ca. 2000 BC), there is only limited ‘direct’ material evidence (like shipwrecks or ship representations), but there can be no question that prehistoric seafarers sailed between the Levantine and/or Anatolian coasts and Cyprus some 12 k years ago, possibly several times per year, in order to transport large ruminants like weaned calves or small wild boar on boats much more sophisticated than we might imagine (Vigne et al. 2013). In the long stretch of time—some 4000 years—between the Late Aceramic Neolithic and the Late Chalcolithic (ca. 6800–2700 Cal BC), it is often assumed that the inhabitants of Cyprus turned their backs to the sea. I would suggest, however, that Cyprus was never truly isolated from the sea that surrounds it: all early seafaring communities had an ‘attitude’ to the sea, and the ‘business of seafaring’ involves travelling upon and making a living from the sea (Anderson 2010:3), enabling not just the transport of animals, mineral, stone and other goods and resources but also the movement of people and ideas—communicating and sharing knowledge across the sea and between different lands, cultures and polities.

In this study, I first present a brief discussion of maritime dispersals in the wider Mediterranean during the late Pleistocene before turning to consider developments on Cyprus during each era from the Late Epipalaeolithic (eleventh millennium Cal BC) through the Prehistoric Bronze Age (early second millennium Cal BC) (for the Protohistoric [Late] Bronze Age, see Knapp 2014). In each section, I discuss an array of material and social developments related to seafaring and seafarers, to maritime interconnections, and to those everyday coastal and marine-related activities that impacted on the foragers, fishers, mariners and farmers of prehistoric Cyprus. In the discussion and conclusion that follow, I attempt to paint with a broader, diachronic brush a picture of everything from rural anchorages to invisible maritime behaviours that may enable us to gain a fuller understanding of seafaring as an everyday practice on the island of Cyprus.

Maritime Dispersals in the Mediterranean

Within the Mediterranean, maritime dispersals on the order of anywhere from 500 kya to 2.6 mya have been argued, contentiously, on the basis of lithics from the Plakias region of southwest Crete (Strasser et al. 2010, 2011; cf. Broodbank 2014; Galanidou 2014; Cherry and Leppard 2015, 2018). Other recent work in the Aegean, however, also indicates the possibility of purposeful navigation during the Pleistocene. For example, at Stelida on Naxos, excavations in the soil of a chert quarry have revealed over 9000 artefacts, including hundreds of tools—blades and hand axes amongst them—in the Mousterian tradition, now dated somewhere between 13 and 200 kya (Carter et al. 2019). Given varying changes in sea level over this long period, these excavations offer potential evidence for the exploitation of lithic resources by hominins (during lowered sea levels of the Middle Pleistocene) or by Homo sapiens of the Early Upper Palaeolithic, the latter quite likely by sea. Other relevant evidence or arguments concerning the likelihood of the very early movement of people to the Aegean islands extends throughout the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic (e.g. Efstratiou et al. 2014; Runnels 2014; Howitt-Marshall and Runnels 2016; Papoulia 2017; Galanidou 2018; Sampson 2019). Further discussion of such evidence, however, would take us too far from our purpose; moreover, there are clearly qualitative differences in water distance to reach islands like Cyprus or Crete. Excepting Crete, the Aegean cases involve little actual distance and considerable inter-island visibility.

Suffice it to say that the often-perceived lack of evidence for Late Pleistocene use or exploitation of islands results in part from the belief that most islands were too impoverished to support non-food-producing hunter-gatherers and in part the notion that pre-Neolithic people had very limited maritime capabilities (Cherry 1990:201; Knapp 2010:90). Moreover, and directly relevant to this study, there is a tendency amongst prehistoric archaeologists working on Cyprus to characterise the island in terms of its isolation from cultural developments taking place on the adjacent mainland, at least during the time between the end of the Ceramic Neolithic and the beginning of the Bronze Age. By contrast, I suggest here that, following the increased levels of maritime activity during the Late Epipalaeolithic (Akrotiri phase) and the Early Aceramic Neolithic, Cyprus was never totally isolated from mainland southwest Asia; the scale and intensity of such links, however, waxed and waned over time (Clarke 2007a, b:127).

Late Epipalaeolithic

Beginning in the eleventh millennium Cal BC, the earlier, occasional forays into the sea (‘seagoing’ or ‘sea-crossings’) must have evolved rapidly, and Cyprus assumed particular importance in the emergence and spread of a more constant and adept use of the sea as a way of life (‘seafaring’) (on the terms quoted, see Broodbank 2006:200, 210; Papoulia 2017:84). Although it is commonly assumed that the earliest phase in an island’s prehistory is one of the least well known, in the case of Cyprus or any other ‘oceanic island’ (what Vigne 2013:46 terms a ‘true’ island), we can be sure that people who first came to the island, and continued to do so over the millennia, travelled by sea, in search of new land, or new resources (fish, shellfish, sea turtles, salt, seaweed, avifauna), or perhaps new opportunities. Moreover, the earliest presence of humans on Cyprus may have resulted in part from the same selective pressure that drove some endemic Pleistocene fauna to extinction around this time, namely the rapid onset of cold, dry conditions throughout the eastern Mediterranean known as the Younger Dryas (ca. 10,700–9600 Cal BC).

Despite the ‘risky’ maritime crossing (Shennan 2018:13), the environmental challenges of the Younger Dryas may have precipitated some emigration from the Levantine ‘core zone’ into surrounding regions, including Cyprus (Wasse 2007:51). In fact, early seafaring and coastal adaptations by fisher-foragers may have benefited from climatic conditions buffered by the oscillations of the Younger Dryas; such conditions would have provided subsistence and other advantages enabling them to adapt more readily to a changing world. Horowitz (1998) suggested that during the early Holocene, the combination of a ‘stratified’ Mediterranean Sea, higher precipitation with some summer rains and the lack of thunderstorms, may have resulted in a calmer sea that made seafaring considerably easier than it was during earlier periods. Currently, however, we still do not know whether increased seafaring predated the Younger Dryas, or whether the halt in rising sea levels associated with this event (Lambeck and Chappell 2001; Lambeck et al. 2014) served to motivate these fishers and foragers even further. In the Mediterranean, there is little material evidence before the Neolithic for the means of transport and very little in the way of other, proxy measures (e.g. remains of domesticated animals and cultivated plants, obsidian) with which one might estimate the size of the boats or the number of journeys involved (Vigne and Cucchi 2005); it should be noted here that the suids from the Cypriot site of Akrotiri Aetokremnos (see further below) most likely represent wild boar ‘managed’ by humans, who introduced them to the island (Vigne et al. 2009).

The material markers of fisher-foragers—e.g. fishhooks, harpoons or boats—are seldom seen in the pre-Holocene archaeological record; this absence of evidence, however, must stem in part from the likelihood that late glacial shorelines are tens if not hundreds of metres beyond present-day coasts and have only begun to be explored systematically in recent years (Bailey et al. 2017, 2020; Flemming 2017; Flemming et al. 2017; Galili et al. 2017a, b: 378–379). In a related study focused on Cyprus, Galili et al. (2016) examined Late Quaternary beach deposits at a somewhat curious selection of 22 coastal archaeological sites (none pre-Neolithic) and concluded that the impact of tectonic uplift (ranging 0.1 to 1.4 m in different sectors of the island) on Neolithic coastal populations of Cyprus would have been negligible compared to that of sea level changes (a rise of 40–50 m during the Holocene). Nonetheless, it is precisely that rise in sea level which would have impacted on any Neolithic or pre-Neolithic sites that lay along Cyprus’s coastal shelf, which itself varies in width from a few hundred metres to 5 km (Galili et al. 2017a, b:393–394). In a more recent study, Ammerman (2020:434–436) claims that 60 ‘hyper-microlithic’ artefacts from the west coast site of Akamas Aspros (‘Dive Site C’) have clear parallels with those recovered from the upper levels of the Ökuzini Cave in Anatolia. Because radiocarbon dates place an upper level at Öküzini in the time of the Younger Dryas (Yalçinkaya et al. 2002), Ammerman argues—without any independent radiocarbon dating—that the lithics from Dive Site C should be considered as Epipalaeolithic in date. Given the ongoing controversy over the technology associated with these lithics and their dating, it is fair to say the jury is still out on the case of Aspros.

Be that as it may, there is secure evidence for an Epipalaeolithic presence on Cyprus from one of the island’s most intricately excavated and well-dated (around 11,000 Cal BC) sites, Akrotiri Aetokremnos (Simmons 1999) (on chronology and terminology, see Table 1). My own view of this site is that is that it was visited periodically by Late Epipalaeolithic seafaring fisher-foragers from the neighbouring mainland, who were perhaps already adept at making short coastal trips. I would also venture to suggest that because their home base on the Levantine coast was threatened by rising sea level towards the end of the Younger Dryas, their subsistence base was in peril (see also Knapp 2010:91–92). In the view of Manning et al. (2010:702–703, Fig. 10), this early human presence on Cyprus corresponds to the time at the end of the cool and arid Younger Dryas climate episode (see also Manning 2014a:22–24, Fig. 10). With the warmer and wetter climatic regime that followed came a time of greater potential for farmers as well as foragers, which would have made the Cypriot environment more attractive to increasingly permanent human populations (during the Initial and Early Aceramic Neolithic periods). Indeed, as evidence from the ‘campsite’ of Vretsia Roudias—likely dated to the Late Epipalaeolithic—in the uplands of the western Troodos suggests, some of these groups must have moved inland, adopting to more localised conditions and shedding their maritime origins (Efstratiou 2014:8; Efstratiou et al. 2018).

Aetokremnos today is a coastal site, situated near the top of a precipitous cliff on the southernmost tip of the Akrotiri peninsula (Fig. 2). However controversial its strata, or however it may be construed in geoarchaeological terms (Mandel and Simmons 1997; Ammerman and Noller 2005; Simmons and Mandel 2007), excavations at this small collapsed rock shelter contained indisputable evidence for its maritime associations: over 73,000 fragments (~ 21,000 individuals) of marine invertebrates, including edible remains of topshell, limpets, crabs, cuttlefish and sea urchins, as well as the vertebra of a grey mullet (coastal species), 73 individual avifauna (e.g. bustards, geese, ducks) and 18 wild (or ‘managed’) pig bones, introduced from the mainland. Amongst the immense collection of marine shells were some 160 shell beads, with examples worked from Antalis (dentalium), Conus ventricosus (cone shell) and (the majority) Columbella rustica (dove shell) (Reese 2006:25). The chipped stone assemblage demonstrates clear parallels with blade/bladelet-orientated and microlithic technologies found in Natufian contexts on the mainland, dated ca. 13,000–10,000 Cal BC (Simmons 1999, 2013).

Some time ago, Le Brun (2001:116–117) emphasized that in order to reach Cyprus, some people had to have mastered the craft of building boats, gained a practical knowledge of waves and currents and nourished a long-term intimacy with marine exploration and the sea. More recently, Vigne et al. (2013), in a paper devoted to examining the relationships between island dwellers and animals (at the sites of Aetokremnos, Klimonas, Shillourokambos) in order to reconstruct possible means of prehistoric voyaging and the boats that made this possible, suggested that these early seafarers likely formed a specialised group or community—distinct from agriculturalists—with some navigation experience and at least basic knowledge of winds, currents, landmarks and possible landing places. They suggested that harnessing wind power with a sail (despite the lack of any evidence for such an early use of the sail) would have made the journey from the mainland much quicker, an important factor when transporting weaned livestock. In any case, by the EAN, such experienced seafarers would have transported themselves as well as large ruminants and other semi-wild animals (cattle, goats, eventually Persian fallow deer) in sophisticated types of sea craft (wild boar could have come in dugout canoes), fitted with a deck and possibly with some sort of device for fixing a mast, i.e. a sailing vessel. Such a vessel would have been a rather rigid, wooden construction, made of two or more dugout canoes lashed together, a configuration that generally resembles a catamaran (Vigne et al. 2013:169–171, Fig. 4) (Fig. 3).

In another recent paper, Bar-Yosef Mayer et al. (2015) considered possible return sailing routes between Cyprus and the surrounding mainland, attempting to assess such factors as the type of watercraft, navigational skills, sea level, sea conditions and currents, and wind regimes. Concerning the type of vessels used to travel between Cyprus and the mainland, they were more equivocal and suggested everything from open rafts or dugout canoes (or double canoes) to multiple-hide boats or even bundles of reeds. Based on their analyses, which assume—controversially—that Late Pleistocene wind patterns were not unlike those of the present day, they suggested that the easiest passage would have been from Anatolia to Cyprus, a full day’s journey. In their view, sea-crossings from the Levant would only have been possible during short periods at specific times of the year (April–October) and under certain weather conditions; such a trip would have required overnight travel. Return journeys from Cyprus to the Levant would have been much easier. Such reconstructions, however, fail to take into account the configuration of Late Pleistocene coastlines (i.e. with extended coastal margins), which would have affected wind and current regimes, which in turn we might expect to have been rather different from today’s wind speeds and storm tracks.

Accepting these limitations to our understanding of the types of vessel used, of sea currents and winds, and of the actual sea routes, Aetokremnos and most likely Roudias nonetheless offer sound evidence for early sea-crossings in the Mediterranean at the end of the Pleistocene. Those who undertook these maritime ventures had the ability to design and construct seacraft and to navigate, most likely on a seasonal basis, across the open sea from some adjacent mainland, be it some 50–60 kms from the nearest point in Anatolia (Galili et al. 2017b:394) or about 95 kms from the nearest point in the Levant. They clearly relied on coastal and marine resources in their diet, mainly shellfish, crabs and sea urchins, and coastal-dwelling marine birds.

Initial Aceramic Neolithic

Ayios Tychonas Klimonas and Ayia Vavara Asprokremnos

The arrival of later seafaring groups at the near-coastal site (today 3 km inland) of Ayios Tychonas Klimonas in the Initial Aceramic Neolithic came almost two thousand years after the fisher-forager presence during the Akrotiri Phase (see Table 1; for site locations, see map, Fig. 4). Amongst the remains associated with maritime activities are 31 certain marine shells (although these may be fossils as opposed to Neolithic), some unknown species of birds, as well as some pendants and beads made of shell (Vigne et al. 2011:10–12, Figs. 9–19, Table 2; Rigaud et al. 2017). In a more recent study, Vigne et al. (2019:3, 8) state that ‘Marine fish and shellfish were not eaten, but freshwater crabs were included in their diet’. From Ayia Vavara Asprokremnos, an inland site some 25 km from the coast (Manning et al. 2010; McCartney and Sorrentino 2019), excavations through 2013 produced some 135 marine shell fragments (mainly used as ornaments and largely Antalis) (David Reese, pers. comm., March 2020). Whilst Clark and Wasse (2020) have suggested that the ‘top-of-site’ communal buildings at Kalavasos Tenta might be seen as part of the same architectural tradition as exemplified by Building 10 at Klimonas and that the ‘Tenta 5’ phase might thus belong to the Initial Aceramic Neolithic, all relevant material from Tenta (e.g. obsidian) is presented below, as part of the Early Aceramic Neolithic.

Occupation at both Klimonas and Asprokremnos signals the permanent presence of people on the island. Asprokremnos is not a typical ‘village’ site, but rather one that may have been involved in the systematic exploitation of mineral commodities (ochre and other pigments) designated at least in part for export to the Levantine mainland (McCartney and Sorrentino 2019:63). Such a scenario suggests that certain people living on Cyprus were seafarers who continued to be engaged within a mainland ‘social milieu’, what McCartney and Sorrentino (2019:75) term ‘a seascape territory including Cyprus … in which groups uninterested in village settlement embraced seafaring’. At Klimonas, early ‘village’ life is attested by several small, round buildings and one, large ‘communal’ structure (Building 10) (Vigne et al. 2019:4, Figs. 1, 8), food storage, the import of obsidian in small amounts (3 bladelets, 1 blade—Briois and Guilaine 2013:179), and the (re)introduction of wild boar (97% of faunal remains, over 500 specimens—Vigne et al. 2011:10–11, Table 2; Vigne et al. 2019:8). The last feature may represent a case of game-stocking, which would have required maritime technology (e.g. larger boats) and skills (more frequent crossings) beyond those of the earlier seafarers to the island (i.e. at Aetokremnos). Although thus far there appears to have been limited emphasis on the exploitation of marine resources, the site at Klimonas suggests that these new, more advanced seafaring groups made sea crossings of 60–90 km, established a semi-permanent if not permanent base, and perhaps stocked the area with a dependable, huntable food source (Vigne et al. 2012:8448).

Early Aceramic Neolithic

Practices associated with seafaring—apparent during the Late Epipalaeolithic as a diverse and mobile response by fishers-foragers during and/or just after the Younger Dryas—seem to have become better established during the EAN (see Table 1). Such practices point to closer maritime interconnections between the various regions of the eastern Mediterranean, not unlike the communication webs that typified the early Holocene ‘forager complex’ in the Levantine Corridor and regions farther east (Sherratt 2007:4–5).

Foremost amongst the material evidence of these practices is the presence of both obsidian and carnelian in Aceramic Neolithic sites. Taking the latter first, Moutsiou and Kassianidou (2019) recently analysed 31 (beads) of the 50 known carnelian artefacts thus far found on Cyprus, mainly from mortuary contexts in the following EAN sites: Parekklisia Shillourokambos (1), Krittou Marottou Ais Giorkis (2) and Kalavasos Tenta (1–agate, not carnelian); the majority of the beads come from Late Aceramic Neolithic (LAN) Khirokitia Vouni (40, of which 27 were analysed). Elemental analyses (portable XRF–pXRF) conducted on these beads suggested at least two geochemical groups (the likelihood of more groups could not be excluded), but the actual source(s)—the nearest known are in Anatolia and the Caucasus—have yet to be determined. The rarity of carnelian, in the Levant as well as on Cyprus, logically suggests that it may have been a prestige item that circulated through various eastern Mediterranean exchange networks (Groman-Yaroslavski and Bar-Yosef Mayer 2015), at least one of which involved maritime movement between the island and the mainland.

The presence on Cyprus of rare stone objects like carnelian, as well as any stone non-native to the island, demonstrates maritime movement and might even indicate the socio-economic practices of specialist mariners. In another recent study, Moutsiou (2019:125) argues that the materiality of rare and exotic raw materials such as carnelian, obsidian or even (local) picrolite would have expressed ‘relatedness’ in both local and extended social domains, which in Cyprus’s case of course also involved sea-crossings. The study of obsidian, more common than carnelian in the EAN villages of Cyprus (especially at the north coast site of Akanthou Arkosyko), provides yet another proxy for tracking long-distance maritime links with the Anatolian mainland, and in particular with two Cappadocian sources (Göllü Dağ, Nenezi Dağ—Moutsiou 2018:237–239, Figs. 3, 4, with further refs.). Şevketoğlu and Hanson (2015:235) noted that chemical analysis of obsidian artefacts from Arkosyko, conducted at the University of Tübingen, indicated a different Cappadocian source, Kömürcü-Kaletepe, long ago identified as a major obsidian deposit exploited during the Neolithic in both Anatolia and the Levant (Renfrew et al. 1966; Perlman and Yellin 1980).

Moutsiou’s (2018) recent study considered diachronic changes in the use of obsidian by examining the quantities, stratigraphic contexts and technological characteristics (primarily blades or bladelets) reflected in assemblages from five EAN and four LAN sites on Cyprus. By far, the largest number (over 4000 pieces) stems from EAN Akanthou Arkosyko (Şevketoğlu and Hanson 2015:227, who also noted the surface presence of obsidian blades at Phlamoudhi Pygadoullia, another coastal site about 11 km east of Akanthou), followed by Parekklisia Shillourokambos (451 pieces) on the south coast. The remaining three EAN sites have much lower quantities: Krittou Marottou Ais Giorkis (66), Kalavasos Tenta (36) and Kissonerga Mylouthkia (24). In striking contrast, LAN sites have far fewer amounts: Khirokitia Vouni (41), Cape Andreas Kastros (13), Kholetria Ortos (2) and Limnitis Petra tou Limniti (1) (Moutsiou 2018:231, Table 1). Obsidian finds from LAN deposits at the north coast site of Klepini Troulli should be added to Moutsiou’s list; they include at least 21 pieces, most likely from a Cappadocian source (Peltenburg 1979:23 Table 1, 30, 37).

Moutsiou’s study demonstrates the long-term use of obsidian on the island, a period of some 3000 years (ca. 8500–5200 Cal BC), although the actual end date of the LAN remains uncertain (Knapp 2013:187–192; Manning 2013:504–507). The most striking feature of her study, however, is the tenfold decline in obsidian use by the LAN (from about 4500 pieces in the EAN to 57 pieces in the LAN). By the following, Ceramic Neolithic period, most sites have only one or two pieces. The Anatolian origin of the obsidian found on Aceramic Neolithic Cyprus, and in particular the technology involved (primarily blades and bladelets with little evidence of core debris), suggest that obsidian was transported as a finished product in maritime exchange networks that possibly terminated at north coast sites such as Arkosyko or Phlamoudhi Pygadoullia; Şevketoğlu and Hanson (2015:227) observed that such sites may have served as ‘gateways’ from which obsidian was distributed to other, contemporary sites on Cyprus (Fig. 5). Finally, as Moutsiou (2018:242) observes, long-distance and especially seaborne travel during the Aceramic Neolithic required substantial planning and was a risky, time-consuming endeavour whose benefits had to outweigh the costs. In her view, the presence of obsidian on Cyprus suggests that the island’s inhabitants were involved in a ‘shared symbolic system’ within the wider eastern Mediterranean, and that its acquisition through maritime exchange networks signalled its social significance in these extensive communication systems.

Overview of excavations in progress at the EAN coastal site of Akanthou Arkosyko. From Şevketoğlu 2006:129, Fig. 1. Courtesy of Müge Şevketoğlu and the Akanthou Rescue Excavation Project

Before examining other maritime-related elements during the EAN, it must be explained that the presence of marine shells and fish bones at a site typically indicates the exploitation of the sea as a resource, either for food (edible molluscs and fish) or for personal decoration (shells of all types). Moreover, the exploitation of coastal resources (fishing, use of marine molluscs) and transmarine travel (seafaring) may represent entirely different practices. Whereas the two are closely linked in the earliest periods treated in this study (Late Epipalaeolithic, Aceramic Neolithic)—when the people who exploited coastal resources were the same as those who arrived from the mainland (i.e. both seafarers and fisher-foragers), during later periods (Ceramic Neolithic, Chalcolithic) after the island was permanently settled, exploiting coastal or marine resources and seafaring (in the broader sense) are not necessarily linked and one does not imply the other. Given the current state of the available evidence, moreover, it is impossible to state whether the technology, equipment and knowledge used in coastal or even deep-sea fishing were the same as those required for transmarine travel (i.e. from Cyprus to or from the mainland). Throughout this study, the point is not to distinguish between marine resource exploitation and transmarine travel, but rather to consider all aspects of maritime life, including a concise, up-to-date presentation of coastal or marine resources as cited in a very broadly scattered and often ignored literature (or as provided to me by David Reese from his unpublished files). I would add, finally, that the abundant evidence carefully excavated and published from EAN sites such as Parekklisia Shillourokambos, Kissonerga Mylouthkia, Kalavassos Tenta and Akanthou Arkosyko demonstrates that it is crucial for field projects to dedicate the resources necessary to identify ichthyofaunal and malacological remains and to determine their counts more accurately.

For example, the ichthyofaunal assemblage from Parekklisia Shillourokambos (Secteur 1 only) consisted mainly (90%) of sea bass and large groupers (4 to 17 kg) (Desse and Desse-Berset 2011:842; Bar-Yosef Mayer 2013:86). In addition, there were 372 pieces of fossil and marine shell, likely used as personal ornaments or tools; other grooved stones with carved geometric motifs may have served as net sinkers (Serrand and Vigne 2011; Bar-Yosef Mayer 2013:89; 2018:211). Some of these grooved stones, made of picrolite and incised with vertical and horizontal hatching, resemble hollow cups or miniature bowls (‘micro-godets’) (Guilaine 2003:334, Fig. 2d; 337–338; Guilaine et al. 2011:1205, Fig. 9); two very similar picrolite objects were recovered at Arkosyko (Şevketoğlu 2018:22–23, Figs. 15–16) (Fig. 6). It has been suggested, rather imaginatively, that these somewhat curious objects represent early boat models and thus are emblematic of the role of seafaring and maritime practices in EAN communities (Guillaine et al. 2011:1205–1209; Şevketoğlu 2018:21–25).

Small hollow cup (< 3 cm) made of picrolite, perhaps depicting a boat. From Şevketoğlu 2018:22, Fig. 15; photograph by İsmail Gökçe. Courtesy of Müge Şevketoğlu and the Akanthou Rescue Excavation Project

The wells at Kissonerga Mylouthkia (EAN 1–3) produced hundreds of fish bones and over 2300 edible marine shells, as well as a fishhook made from a piece of pig tusk (lowest fill of Well 116) (Peltenburg et al. 2001:76; Croft 2003:50; Cerón-Carrasco 2017). Remains from EAN Kalavassos Tenta include 471 marine shells (Reese 2008a); Bar-Yosef Mayer (2018:212) suggests that some of the perforated shells—Columbella, Conus, and the lips of two Semicassis undulata (helmet shell)—may have served as personal ornaments. From Arkosyko comes a diverse array of deep-water marine species (hake, dogfish, shark, tunny), some smaller inshore fish, at least 36 marine shells (dentalium, cowrie, bivalves) and the remains of ten complete Caretta caretta (sea turtles) (Şevketoğlu 2002:101–102, 105, 2006:125, 136, Fig. 24; Şevketoğlu and Hanson 2015:235–236). According to an unpublished report by David Reese (pers. comm., March 2020), excavations conducted through 2014 at Kritou Marottou Ais Giorkis—today about 25 km from the sea—produced a total of 982 marine shells, 189 freshwater shells and 9 fossils.

Another site at Nissi Beach, today situated on a cliff just above the southeast coast, produced marine shellfish remains in two distinct assemblages, one EAN and the other Ceramic Neolithic (Thomas, in Ammerman et al. 2017:129–135). Thomas maintains that the EAN shells were dominated by those used for ornamental or other non-dietary purposes, whilst the majority of those from Ceramic Neolithic deposits represent food debris. Thomas adds an environmental dimension in the attempt to understand these assemblages: in his view, because the coast would have been at least one km or more from the sea during the EAN, any shellfish gathered for food may have been consumed and discarded closer to the coast; only those shells with perceived ornamental or symbolic value would have been carried back to the site (yet only one, a Conus shell, had a hole for stringing). By the Ceramic Neolithic, however, when the shoreline would have lain closer to the site (as it does today), the marine shells may have been processed and consumed at the site (yet none of the Nissi Beach shells are burnt, and none of the few land snails excavated are regarded as food remains—Ammerman et al. 2018:379–380).

Excavated during the 2008 and 2009 seasons at Nissi Beach in an area of just 27 m sq, these two assemblages tally some 250 individual shells (MNI) from a total of 700 identifiable specimens (NISP) (Thomas, in Ammerman et al. 2017:130). Thomas thus argued that the density of shells at Nissi Beach ‘… is very high, suggesting an intensive focus on the exploitation of marine resources at the site’ (Ammerman et al. 2017:135). In comparison with sites such as Akrotiri Aetokremnos, Kalavasos Tenta or Cape Andreas Kastros, however, the density of shells is not that high (David Reese, pers. comm., March 2020). It may also be added that amongst the marine shells excavated at Nissi Beach, two Patella caerulea (limpets) recovered in 2007 produced AMS dates falling in the eighth millennium Cal BC (i.e. EAN 2–3; Ammerman et al. 2008:15, 2017:114), whilst a single cowry shell has been dated to the beginning of the seventh millennium Cal BC (Ammerman et al. 2017:127); three further shells date much later, to the fifth millennium Cal BC (Ammerman et al. 2017:129, Fig. 11). Simmons (2014:164), however, quite rightly cautioned that it is unclear whether any of the EAN shells represent cultural deposition or were simply washed up on the shore.

Looking at the broader picture, which involves transmarine interactions (e.g. obsidian trade, other overseas impacts) as well as the exploitation of coastal and marine resources, both Watkins (2004) and Finlayson (2004) regarded the permanent settlement of Cyprus during the EAN as a process that opened up new spheres of interaction; of necessity these were maritime spheres that involved people who had considerable seafaring skills and fishing experience. Peltenburg (2012:78) also argued that seaborne travel involving the coastal or near-coastal sites of this period would have facilitated contacts not just for long-range obsidian networks but for marriage partners, information and other social exchanges. The ongoing restocking of the island’s fauna (Kolska Horwitz et al. 2004:38), the use of circular architecture reminiscent of its Levantine (PPNA) heritage, and the continued appearance of new features in the chipped stone repertoire all suggest that the earliest Neolithic inhabitants of the island of Cyprus continued to have embedded interactions with their coastal counterparts on the mainland (already emphasized by McCartney 2007:72–73).

Late Aceramic Neolithic (LAN)

The coastal site of Cape Andreas Kastros at the north-eastern tip of the Karpass Peninsula produced an array of bone fishhooks, stone rings (net sinkers?) and extensive fish remains (Reese 1978; Le Brun 1981:61–62, 93–94, 203 Fig. 56; Desse and Desse-Berset 1994). Over 4500 marine fauna remains—the majority Columbella (dove shell), Phorcus turbinatus (topshell) and Patella spp (limpets)—were tallied, and some remains of marine crabs (350) and sea urchins were retrieved (David Reese, pers. comm., March 2020; see also Cataliotti-Valdina 1994). Whereas the fish bones—nearly 4000 identified—derive mainly from near-shore species, other large, deep-water, migratory fish were recovered, including tuna (36.5% of the assemblage); to catch the last requires skilled fishermen and specialised tackle (Koutsouflakis 2001:358–360). Other, LAN north coastal sites such as Petra tou Limniti (12 marine shells, 25 fish bones recovered) and Troulli (Gjerstad et al. 1934:1–12, 63–72) might have had equally impressive remains, but were excavated long before archaeologists working on Cyprus did much sieving or became concerned with ichthyofaunal or malacological remains.

From early excavation campaigns at Khirokitia Vouni (Dikaios, Stanley Price and Christou), today some 6 km inland, a limited number of fish bones were recovered, all from large fish, yet nearly 650 marine mollusks were identified, some from later, Ceramic Neolithic levels (Stanley Price 1976:1; Watson and Stanley Price 1977:236–237; David Reese, pers. comm., March 2020). Nearly 250 fish bones—mainly grouper and sea bream—were retrieved from later excavations (A. Le Brun) at Khirokitia (Desse and Desse-Berset 2003:282), and many more remain to be published. Le Brun’s 1977–1978 and 1980–1981 excavations also uncovered 220 marine invertebrates (Demetropoulos 1984). From Kholetria Ortos, today some 9 km from the coast, survey and excavation produced 139 marine shells (David Reese, pers. comm., March 2020).

At both Khirokitia and Kastros, remains of grouper, sea perch, sea bream (sargus) and mullet were identified (Le Brun 1993:75–76, 1997:37). The unique fish ‘amulet’, a surface find at Khirokitia, may represent an attempt to portray one of these species (Dikaios 1953:302, 306, Fig. 107). Engraved pebbles—with a grid of incised lines on one or both sides—and conical stones, decorated with chevrons on their side and a chequered or gridded pattern on their base, were found at Khirokitia (Dikaios 1961:37, Fig. 19; Astruc 1994:236–243, 270–277, Figs. 96–99; Le Brun 1997:36, 38, Figs. 34–35). Engraved pebbles were also recovered from LAN Kholetria Ortos (Simmons 1996:37, Fig. 2), and the patterns on examples from both Khirokitia and Ortos are quite similar to those on engraved and grooved stones from EAN Shillourokambos (Guilaine 2003:334, Fig. 2). At least one engraved, cross-hatched (sandstone) pebble was recovered at the Ceramic Neolithic site of Kalavasos Kokkinoyia; it was a surface find, however, and there are no other indications of a LAN phase there (Clarke 2004:59, Fig. 3.3).

Steel (2004:58) suggested that these pebbles and conical stones might have served either as weights for fishing nets or as tokens in a social storage system. Stewart and Rupp (2004:168–171) added that the pebbles could have been used in exchange transactions. The engravings on the pebbles from Khirokitia and Ortos might well represent fishing nets, whilst the engraved stones could have served as net sinkers. It should be noted, moreover, that pebbles engraved with geometric designs turn up frequently not just on LAN Cyprus but also in Levantine aceramic and ceramic Neolithic contexts, from the Natufian to the Pottery Neolithic (Simmons 1996:37; Peltenburg 2004:83; McCartney 2007:77). Dentalium shell, often incised or decorated, and found mainly in burials at Khirokitia, is also associated primarily with mortuary deposits in Levantine (Natufian through Neolithic) contexts (Reese 1991; Boyd 2002:141). Such shells may point to another marker of maritime exchange, if not some ancestral link. The engraved pebbles from Cyprus and the Levant certainly overlap in time, suggesting that both regions were in maritime contact with one another and perhaps shared a common symbolic or referential world. McCartney (2007:77) has suggested that the analogous appearance of engraved pebbles in LAN Cypriot and contemporary southern Levantine sites may be indicative of a regional interaction sphere throughout the coastal eastern Mediterranean (see also Steel 2004:56).

The tendency for archaeologists working on Cyprus to portray the later Neolithic (LAN and Ceramic Neolithic) and all subsequent periods before the Bronze Age in terms of isolation fails to take into account its coastal milieu, and the waxing and waning of maritime contacts associated with its coastal and near-coastal communities. As far as the LAN is concerned, although there is a notable drop-off in the occurrence of obsidian, Cyprus continued to be involved in the exchange of goods in the eastern Mediterranean and marine resources continued to be exploited. This is indicated by a range of different materials, exotic or otherwise, from various sites, and includes the obsidian (at least 57 pieces), some 40 carnelian beads (including a ‘butterfly bead’) from Khirokitia Vouni, and the white marble rings from Kalavasos Tenta (Dikaios 1953:303–306; South and Todd 2005:305–307, Fig. 64). Moreover, as McCartney (2010:192) emphasized, the somewhat earlier vaisselle blanche from Ais Giorkis (Simmons 2007:242) and the later pottery technology of the Ceramic Neolithic also point to ongoing maritime contacts between Cyprus and the surrounding mainland.

Already during the initial settlement of Cyprus, people would have taken with them everything they needed to establish a new life for themselves on the island: their material culture and their shared histories and memories (Jones 2008:90), especially their knowledge and experience of the coast and the sea. Weninger et al. (2009:405–410) concluded that the ‘8200 BP event’ (i.e. ~ 6200 Cal BC), a cold snap that lasted about 150–200 years (Rohling et al. 2002), led to the desertion of the island toward the end of the LAN. There is little support for such an idea (see, e.g. Flohr et al. 2016), and it seems equally plausible that, as far as seafaring is concerned, the ameliorating climatic conditions and rising sea levels that followed this ‘event’ may have led to a more navigation-friendly sea. Indeed, during the LAN, a broad and diverse array of material, faunal and malacological evidence demonstrates ongoing maritime activity and indicates that the people of LAN Cyprus had not only adapted to a new, insular way of life, but also maintained some level of overseas contacts with people in the coastal Levant.

McCartney (2007:79) regarded such evidence as indicative of an exchange of goods and ideas conducted by independent coastal communities within a loosely organised, non-intensive interaction sphere. Even if the material indicators of exchange are not as evident as they were during the EAN, Cyprus was clearly not sealed off from the cultures surrounding it during the LAN. Just what became of this maritime interaction sphere during the subsequent Ceramic Neolithic and especially Chalcolithic periods is a topic fraught with problems and replete with questions that still cannot be answered satisfactorily.

Ceramic Neolithic

During the Ceramic Neolithic (CN), a range of evidence from coastal communities like Paralimni Nissia and Ayios Epiktitos Vrysi reveals diverse patterns of marine resource exploitation. Excavations at Nissia, a small hillock today situated right on the seashore with direct access to a natural harbour (Flourentzos 2008:3), produced only moderate numbers of fish bones and two crab claws but 16 species of molluscs with over 950 individuals (Flourentzos 2003:77; Reese 2008b). The diet of the inhabitants at Nissia, however, also relied heavily on hunting: some 77% of the mammal bones recovered from the site belonged to deer, which represents about 90% of the overall meat supply (Croft 2008, 2010:135). The variety of stone objects recovered from the site included some weights and what are described as loom weights; these were more likely sinkers for fishing (the earliest known loom weights on Cyprus are dated over 1000 years later). Amongst Nissia’s small finds was a distinctive fish-shaped figurine (Flourentzos 2008:87, Fig. 24:319). Stone fishhooks from Nissia (Flourentzos 2003:82) and bone versions of the same found at Vrysi (Peltenburg 1983:24, 124, Fig. 5: 13) and Sotira Teppes (Dikaios 1961:203, pl. 104:233) point to fishing activities. Excavations at both Vrysi and Teppes also uncovered some perforated or grooved stones and stone discs—dubiously identified as spindle whorls—that could have served as net sinkers (Dikaios 1961:202, pls. 91, 103; Peltenburg 1978:58–60, Fig. 3W).

The community at Vrysi—today situated on a headland some 14 m above sea level along Cyprus’s north central coast—also exploited various marine resources, including 36 different marine mollusc species with over 1500 examples, mainly (edible) Patella and Phorcus, as well as 159 crab fragments (Ridout 1983; David Reese, pers. comm., March 2020). A number of fragmentary bones from Vrysi were identified as marine turtle (Legge 1983:85). Croft (2010:135–136) found it curious that excavations at coastal sites such as Vrysi and Nissia produced only a limited number of fish bones and suggested that fish may be seriously underrepresented in the faunal record of both sites (see also Legge 1983:86–87). One likely reason for the small number of fish at Vrysi (60 bones in 20 deposits) and Nissia (9 bones in 7 deposits) is that water-sieving/flotation was not carried out consistently.

Some ten kms east of Vrysi lies the site of Klepini Troulli; the promontory on which the site is located ends at a rocky plateau extending east and west. At the foot of the east slope lays an anchorage that could have accommodated small craft (Dikaios 1962:63–64, Fig. 32). Amongst the materials from Troulli were 41 marine shells, including one trimmed dentalium that may have served as a necklace spacer (Peltenburg 1979:23, 24, 34, Fig. 3.17).

Significant numbers of marine shells turned up at the inland site (today 5 km from the south coast) of Kandou Kouphovounos, situated atop and along the western and southern slopes of a small hill, close to the Kouris River. Excavations at the site recovered some 35 marine species, dominated by cockles (97 fragments), Hexaplex trunculus (murex, over 120 fragments) and Ostrea edulis (oyster, 31 fragments) but also including 23 crab fragments and 2 sea urchins (Mantzourani 2003:98; Karali 2019; Mantzourani and Voskos 2019:398). In Area 2 at Dhali Agridhi, another inland site, Lehavy (1989:211) reported that fossilized fish teeth and conch-type seashells were used to make beads, but at least three of the fish teeth have now been identified as naturally broken freshwater crab claws (Reese, pers. comm., March 2020). Moreover, the needle or pendant Lehavy (1989:209, 215, Fig. 13c, pl. 8c) described as a ‘pierced tusk of a wild boar’ has been identified by Reese as the water-worn distal end of a Glycymeris (dog cockle).

Obsidian turns up in the CN, albeit rarely: there is one nugget from Vrysi (Peltenburg 1985:94) and two blades and a bladelet from Kalavasos Kokkinoyia (McCartney 2007:83–84). McCartney suggested that these few pieces of obsidian may have reached Cyprus via an ‘infrequent trinket trade’, which also involved the southern Levant. As already noted above, one cross-hatched pebble—like those found at Khirokitia and Ortos and thought to represent fishing nets—was recovered from the surface at Kokkinoyia, and two triton shells were excavated in Chambers 105 and 221 (Clarke 2004:59, Fig. 3.1, 3; Clarke 2007b:21). Surface collections and excavations at Kokkinoyia over many seasons have also produced 30 invertebrates, mainly limpets (David Reese, pers. comm., March 2020).

Although I have argued here and elsewhere that the sea has frequently formed part of everyday life on Cyprus, in my view none of the coastal or near-coastal CN sites, except possibly Nissia (or LAN Cape Andreas Kastros), could be construed as an archetypal ‘Mediterranean Fishing Village’ (MFV) (Galili et al. 2002; Knapp 2010:108–109). Even so, the development of an economy based on such a model may have incentivized contacts with other coastal sites around the island and with the adjacent mainland. Moreover, as McCartney (2007:88–89) suggested, the MFV model provides a framework for understanding some of the evidence (e.g. obsidian, carnelian) of limited interaction between Cyprus and the rest of the eastern Mediterranean during the CN. Other links in chipped stone technology with the central and southern Levant led McCartney (2007:84) to propose that Cyprus was part of an eastern Mediterranean exchange system as this time. Although most scholars still tend to emphasize the increasing isolation of Cyprus’s CN villages, the evidence discussed here indicates that people, goods and ideas were still moving across the sea and that fishing still supplemented the diet. As McCartney (2007:90) concluded: ‘Cyprus need not be perceived as being quite so far off on the periphery as previously perceived but as [a] regular participant in a coastal milieu’.

Chalcolithic

The picture of maritime connections, seaborne networks and seafaring as painted thus far becomes less apparent during the Chalcolithic period. Although seafarers must have been significant players in the movement of such goods (obsidian, carnelian, chlorite, faience), ideas and innovations (lithic technology, ceramics) as existed during this period, the relevant material and faunal data are thin on the ground.

During Period 3 at Kissonerga Mylouthkia, a severely eroded site today situated very close to the sea on the southwest coast, dentalium shell was used as bodily ornament, and some perforated or grooved stones and stone discs may have served as net sinkers (Peltenburg et al. 2003:181–182, Fig. 68.3, 5). A copper fishhook also turned up at Mylouthkia, but its attribution to Period 2 is somewhat problematic (Peltenburg et al. 2003:191, Fig. 71:12, pl. 16.8). At nearby Kissonerga Mosphilia, two ‘ceremonial’ units produced a total of 138 marine shells (mainly Phorcus sp.) as well as some crab remains (Reese 2017: 231–232). From Kalavasos Ayious come various artefacts made of carnelian, calcite, marble and possibly ivory (Todd and Croft 2004:219), all evidently non-native but with origins that remain uncertain. Molluscs recovered at Ayious include 52 marine shells, 3 crabs (1 marine and 2 freshwater) and 24 fossils (Reese 2017:219–222; see also Demetropoulos and Eracleous-Argyrou, in Todd and Croft 2004:212). Some 110 marine shells (98 individuals) were excavated at Middle Chalcolithic Prastio Agios Savvas tis Karonis Monastery in southwestern Cyprus, today some 17 km from the sea (Reese, in Rupp et al. 2000:287–298).

In the Dhiarizos River Valley, about 4 km up from the coast, the site of Souskiou Laona was located ‘… at the nexus of communication routes along the coast and between the coast and the mountains’ (Peltenburg et al. 2019:5, pl. 3.2). Souskiou’s own nearby cemetery and those of Vathyrkakas include a remarkable array of picrolite cruciform figurines and other mortuary offerings, including literally hundreds of segments of dentalium shell, likely used in necklaces or other body paraphernalia (Reese 2017:227–231). The settlement assemblage included almost 400 marine gastropods and bivalves, some 2600 dentalia and 52 crab claws (Ridout-Sharpe 2019:302, Table 19.1). The numbers of dentalia found in individual rock-cut features in the Laona cemetery range from one to over 1300 ‘segments’ (Fig. 7), and the amount and condition of these dentalia are similar to those recorded at Vathyrkakas (Ridout-Sharpe 2019:304–306, Table 19.4). The molluscan assemblage at the Laona settlement differs from those at the contemporary sites of Kissonerga Mosphilia/Mylouthkia and Lemba Lakkous, which were dominated by edible Patella (limpets) and Phorcus (topshells).

Dentalia (small find no. 467) from the Middle Chalcolithic cemetery (Tomb 216) at Souskiou Laona. From Peltenburg et al. 2019:pl. 106.11; photograph by Edgar Peltenburg. Courtesy of Lindy Crewe and Diane Bolger

Some of the best-known sites of the Middle Chalcolithic (Souskiou Laona, Kissonerga Mosphilia and Mylouthkia, Lemba Lakkous) are found in the island’s southwest coastal region. Kissonerga Mosphilia, situated on gently sloping ground about one km from the present-day coast, is the largest (ca. 12 ha; Mylouthkia about 6 ha, Lakkous 3 ha). Lemba Lakkous is situated on a series of terraces overlooking a narrow coastal plain, whilst Laona—as already mentioned—is positioned atop a prominent, narrow ridge some 4 km from the sea. Viewshed analysis, however, indicated that even this inland site was oriented towards the sea and the Ktima lowlands (McCarthy, in Peltenburg et al. 2006:101–102).

External contacts during the Chalcolithic era are limited; the only certain imports are small amounts of carnelian and obsidian. Peltenburg (1991:109) regarded the chlorite and faience from Mosphilia as heralding ‘the gradual breakdown of Cypriot insularity’. Faience is also present at Souskiou Vathyrkakas and the contemporary cemetery at Laona, whilst burials at Mosphilia, Lakkous and Vathyrkakas Cemetery 1 contained notable numbers of dentalium shell. The occurrence at these sites of non-native materials such as faience, carnelian, chlorite and several species of shell may indeed signal an uptick in off-island exchange, and maritime contacts with the adjacent mainland thus may have continued on some limited scale throughout the fourth millennium BC.

From a maritime perspective, the coastal or near-coastal locations of these well-excavated Chalcolithic sites (Mosphilia, Mylouthkia, Lakkous) in southwestern Cyprus, on sloping ground with commanding views of the surrounding sea, at least raise the possibility that interactions between them may have been conducted by ‘part-time seafarers’ on small seacraft (‘coasters’) along the littoral zone (Duncan Howitt-Marshall, pers. comm., January 2020), what Tartaron (2013:188–189) defined as ‘coastscapes’. Regarding external maritime contacts, Peltenburg (2006:168–170) has allowed that the use of faience, as well as early metalworking, may have been imported technologies, even if the evidence remains equivocal. But do the ‘foreign’ artefacts from Ayious and non-native materials (chlorite, faience) from Mosphilia and Vathyrkakas actually add up to increasing communications with the surrounding world? We have to consider the possibility that Chalcolithic Cypriotes adopted an intentional strategy of maintaining a distinct, somewhat circumscribed island identity, what Peltenburg (2004:84) termed a ‘dynamic of stability’ for the preceding periods. However, by the end of the fourth and during the first half of the third millennium BC, i.e. during the Late Chalcolithic and the subsequent, early phases of the Prehistoric Bronze Age, Cypriot contacts with Anatolia, the Aegean and perhaps even the southern Levant increasingly come to the fore.

Late Chalcolithic

Amongst the rich and diverse finds from the Pithos House of Period 4a at Kissonerga Mosphilia are several related to maritime practices and seafaring: triton shells, annular shell pendants, evidence for the working of shell, a concentration of conical stones similar to west Asiatic tokens (Schmandt-Besserat 1984) and some (likely imported) faience beads (Peltenburg et al. 1998:37–43, 252–254). Nearly 1000 samples of local mollusca (103 species) from Kissonerga Mosphilia were examined; some are regarded as food remains, others as ‘ritual’ in nature, still others as ornamental—all in relatively low numbers of actual individuals (Ridout Sharpe in Peltenburg et al. 1998:224–229). Some 80% of the 500 recorded beads from Mosphilia were made from dentalium shell which, like the marine shell and other types of beads found, were manufactured on-site (Peltenburg et al. 1998:192–193). Areas I and II at Late Chalcolithic Lemba Lakkous produced over 200 invertebrates, including 36 crab claws (Reese 2017:232–233). Reese (2003:456) lists some other Middle–Late Chalcolithic sites that also produced limited quantities of marine shells. Some of the grooved stones found at Mosphilia (nos. 27–28) and Lemba Lakkous (4, 6, 8) might well be defined as net sinkers (Peltenburg et al. 1985:288–289, Fig. 85, 1998:195–197, Fig. 99).

In terms of external connections, at some point during the transition to the Late Chalcolithic (ca. 2800–2700 Cal BC), lead isotope analysis of some metal items found at Pella in Jordan (an axe and two daggers—Philip et al. 2003) and at Hagia Photia on Crete (a fishhook and an awl—Davaras and Betancourt 2004:4) indicates they were made of copper consistent with a Cypriot ore source (Stos-Gale and Gale 2003:91–92, Table 5). There are no other indicators of the production or export of Cypriot copper at this early date, but as Peltenburg (2011:6) noted much of our information on the mining and distribution of Cypriot copper at this time comes from the copper-poor south and west of the island, not the copper-rich north (i.e. the northern Troodos, not the north coast). With respect to imports, pXRF of a small copper axe/adze from the Late Chalcolithic site of Chlorakas Palloures in southwest Cyprus revealed that it contained a minute amount of tin; since tin is not present in Cypriot copper ores, this object was either imported or made with imported raw materials (During et al. 2018:19, Figs. 4, 6). There are also signs of likely external contacts in the faience and metal finds from Late Chalcolithic contexts both mortuary (e.g. Souskiou Laona) and domestic (Mosphilia, Laona) (Peltenburg et al. 1998:188–189). Two chisels from Kissonerga Mosphilia (KM 694, 2174) and a blade from Lemba Lakkous (LL 209) analysed by pXRF bear traces of tin; KM 2174 may even be characterised as bronze since it contained 3.3% tin (Kassianidou and Charalambous 2019:283, Table 16.1, 286).

Moreover, some level of connections with or inspiration from Anatolia and the eastern Aegean is indicated by various types of materials, designs and features. Peltenburg (2007:153–154) singled out certain changes in the materiality of the Late Chalcolithic—pottery production, copper metalworking, spurred annular pendants and faience beads, stamp seals and conical stones—as reflecting non-native practices (but cf. Webb and Frankel 2011:33–35 on the specific timing of some of these ‘innovations’ at Mosphilia). In his view, such evidence confirmed seaborne activities along the southern coast of Anatolia that ‘profoundly affected the islanders’ (Peltenburg 2007:153; see also Bolger and Peltenburg 2014). He thus suggested that we are dealing with an insular selection and adaptation of certain material traits that he viewed as the result of maritime initiatives undertaken by the Cypriotes themselves. In sum, from a maritime perspective, whilst the evidence for fishing may be slim, molluscs were abundant and used for both eating and manufacturing beads, suggesting that the ‘coastscape’ of southwestern Cyprus, at least, was still being exploited by mariners or fishermen using small seacraft. However, with the possible exception of imported tin or copper objects at Mosphilia, Lakkous and Palloures, the nature and extent of external relations remain uncertain at this time.

Prehistoric Bronze Age (Early–Middle Cypriot)

Setting aside the now rather muted debate over what lay behind the increase in cultural contacts with southern or southwestern Anatolia at the outset of the Prehistoric Bronze Age (PreBA)—i.e. whether we are dealing with a ‘population movement’/‘colonisation’ from Anatolia (Webb and Frankel 2007, 2011) or with a case where the ‘Anatolianising’ features seen in PreBA 1 material culture were the result of hybridisation practices (Knapp 2013:264–277), for the purposes of this study it is more important to note that Cyprus’s maritime interactions with the surrounding regions were on the rise during the third millennium BC. Studies by Şahoğlu (2005) and Webb et al. (2006) indicate that some communities on the north coast likely participated in a maritime interaction sphere that linked Cyprus, Anatolia and parts of the Aegean as early as 2400 Cal BC, involving the possible import of copper ingots as well as copper and bronze artefacts. Moreover, Webb and Frankel (2011:30) have suggested that human movement to the island at this time involved a ‘transported landscape’ wherein people brought with them resources—like cattle and donkeys—that were unavailable on Cyprus. However, because our knowledge about Late Chalcolithic settlement along the north coast remains quite limited (Georgiou 2007:418–421; Manning 2014b:24–25), and because virtually no excavations have been conducted in the occupied north since 1974, we have a very incomplete picture of Cyprus’s external relations during the mid-late third millennium BC.

Constraints both natural and cultural may have limited foreign contacts during the PreBA, but constraints may also be seen as potentials. Distance in and of itself, as well as (coastal or inland) location, seems to have had little impact on Cyprus’s external contacts at this time. On a broader level, seafaring technology in the Mediterranean during the third millennium BC was almost certainly impacted by the deep-channel fishing and river sailing boats of the Nile (Broodbank 2010:255; Ward 2010), and the development of large seagoing vessels must have played a pivotal role in shaping the maritime world of the third millennium BC, not least the increasingly sophisticated trade networks that emerged along the Levantine coast (Marcus 2002).

On Cyprus, the Philia phase was marked by the establishment of new settlements in agriculturally productive areas, along routes of transport, near to metal extraction zones and in close proximity to coastal outlets (Webb 2014:355–356). Because several Philia phase sites are located on or near the coast, it may be that proximity to the sea was a key factor in choosing where to live (Webb and Frankel 1999:7–8). Philia phase Vasilia, for example, was said to have an excellent harbour (Webb et al. 2009:247), perhaps better described as an anchorage. Another key settlement located along the north coast and occupied from Early Cypriot (EC) II through Middle Cypriot (MC) III was Lapithos Vrysi tou Barba (Webb 2016:57). Whereas the actual settlement site or sites remain unknown, the cemetery at Vrysi tou Barba extends along the coast and runs inland for several hundred meters. Thus, we may assume that settlement lay on or near the coast, close to a small protected bay and thus ideal for an anchorage; by the early second millennium BC, Lapithos may well have become involved in seaborne trade (Manning 2014b:25; Webb 2017:132; Webb and Knapp 2020). Whilst the scale of Cyprus’s overseas trade at this time must be seen in context (Knapp 2018:171), and settlement data are needed to confirm this scenario, we can at least suggest that an anchorage at Lapithos could have functioned as a proto-harbour. A north coast port like Lapithos would have given elites some control over external exchange, perhaps even enabled them to establish direct access to copper ores and to oversee the movement of other goods and resources. Indeed, Webb and Frankel (2013:221, 223; Webb 2019:87, 85, Fig. 16) suggested that some of the copper produced at Ambelikou Aletri during the MC I period may have been shipped north to Lapithos by sea (via Cape Kormakiti), whilst the occurrence at Ambelikou of some ceramic vessels from farther west may point to coastal links with the Khrysochou Bay area.

Beyond material indicators of intensifying foreign contacts during the early second millennium BC (Webb 2019,79–82; Webb and Knapp 2020), cuneiform documentary evidence for the use of Cypriot copper in western Asia (Mari, Babylon) at this time (Sasson, in Knapp 1996:17–19) points to maritime trading ventures that must have involved some people from Cyprus, whether producers or distributors. All this would have required groups or communities of specialist seafarers to transport raw materials, finished goods and people to and from the island.

There are three ceramic models from the PreBA that possibly may represent boats (Knapp 2018:96–97; Frankel 1974 seems sceptical that any Early or Middle Cypriot model actually represents a boat). The first is an enigmatic vessel from Bellapais Vounous (Tomb 64.138), possibly of EC date, which Basch (1987:70, 72, Fig. 137) thought might represent the earliest depiction of a Cypriot ship (Fig. 8). The second is a largely reconstructed Red Polished III (Early Cypriot?) object of unknown provenance, now in the Louvre (Westerberg 1983:11, no. 4, Fig. 4). The third is a White Painted II model of MC I date, also of unknown provenance and now in the Louvre, perhaps depicting a boat with rounded hull and projecting stem- and stern-posts (Westerberg 1983:9–10, no. 1, Fig. 1; Basch 1987:70–71, Figs. 132–135).

Dentalium (or ‘tusk’) shells are quite common at PreBA sites, in both domestic and funerary contexts, whilst other marine molluscs—helmet shells, cockles, dog cockles—are also attested. They occur at inland sites like Marki Alonia from the Philia phase through the MC period, largely as dentalia used in necklaces (Reese and Webb, in Frankel and Webb 2006:257–261), and at MC Alambra Mouttes (triton shells, dentalia, murex) where they were used in necklaces and other ornaments (Reese, in Coleman et al. 1996:482–484). Excavations at EC and EC/MC Politiko Troullia, today located some 40 km from the south coast, produced 45 marine shells and 2 marine crabs (David Reese, pers. comm., April 2020). Early excavations at the EC site at Sotira Kaminoudhia, today located some 5 km from the coast, produced 41 marine shell fragments and 5 crab claws (Reese 2003:455); later seasons (2001–2002, 2004) turned up 89 marine shells, 6 crabs and 1 fish bone—from a barracuda (Reese, pers. comm., March 2020). Excavations through 2015 at the Middle Cypriot site of Erimi Laonin tou Porakou, located some six km from the coast, produced 26 marine shell fragments from five different species (Reese and Yamasaki 2017). None of the species recovered were suitable for producing coloured dyes, so there is no obvious link between the marine molluscs recovered and the textile workshop proposed for the site. An almost complete necklace found in the cemetery at the site (Tomb 240) was made from 15 sections of dentalium shell along with three picrolite pendants and two picrolite spacers. At the southwestern near-coastal site of Kissonerga Skalia, from fill deposits overlying two well preserved floors in an area dated anywhere between EC I–MC I (ca. 2400–1900 BC), come two copper-based fishhooks as well as other evidence (crab, edible shellfish) associated with marine exploitation (Crewe et al. 2017:244, 246, Fig. 7.1).

At the EC-MC site of Pyrgos Marvoraki, today situated some 4 km from the southern coast, excavations have produced 137 marine shells, including eight Hexaplex, one Bolinus brandaris and one Stramonita haemastoma (Carannante 2010:160): all three species represent the only colour-yielding gastropods found in the Mediterranean (Cardon 2007). Lentini (2009:165), however, stated that 280 complete Hexaplex shells came from a single room at Pyrgos and so, as ever, it is difficult to know how to evaluate materials reported from this site. Elsewhere, Lentini (2004:39) cited some unspecified ‘micro-analytical techniques’ conducted on some ‘clots’ of red/purple material (Lentini 2004:26–27) that indicated a high concentration of bromine, which to him suggested the use of purple dye (although bromine occurs naturally and in higher levels along the south coast). Although this would represent an unprecedently early date for the purple-dye industry, as Reese (2018:542) notes, the small number of shells securely identified at Pyrgos does not inspire confidence in the notion that purple dye was actually produced at the site.

Discussion and Conclusions

Cyprus is the only large island in the eastern Mediterranean, and its presence would have been obvious to anyone travelling by sea—especially from nearby Cilicia or north Syria. The sea’s currents and the prevailing westerly winds meant that sailors en route from the Aegean to the Levant or Egypt had to pass close by the island; at least during the Late Bronze Age and in later periods (especially the Late Roman), this ensured that Cyprus became a nodal point in the maritime routes of the eastern Mediterranean (Demesticha 2019; Leidwanger 2020:127–136). Sea travel from Cyprus to and from the Levant or Anatolia was not straightforward because of nautical elements like currents and winds, sudden storms or low temperatures, but diverse and complex modelling exercises suggest that such travel would have been possible at different times of the year and under certain weather conditions (Bar-Yosef Mayer et al. 2015). Using space–time cartograms to take account of variables and rhythms that may have affected the sailing performance of ancient seafarers, Safadi and Sturt (2019:6) note that: ‘… winter time seems to afford an uninterrupted access for undertaking journeys across the Levantine Basin, to Cyprus and Anatolia, rather than relying on coastal pilotage along the Levantine coast and solely summer sailing’. Such models offer insights into movements of people and chains of interconnectivity that linked Cyprus with the Levantine coast, Anatolia and, eventually, Egypt.

Throughout the Aceramic Neolithic periods of Cyprus, some (Levantine and/or Anatolian-based) mariners were actively engaged in transferring to the island people, livestock, crops, exotic goods and artefacts, and raw materials. Such recurrent voyages to the island precipitated the emergence of a maritime interaction sphere, what Howitt-Marshall (2020) has termed ‘the cultural creation of a maritime space’. During the Ceramic Neolithic, a range of material from Cyprus’s coastal communities—fishbones and fishing paraphernalia, marine shells, some non-local resources—indicates that the seas surrounding the island continued to be exploited, to supplement people’s diet or as part of their everyday practices, evidence of their continuing involvement in the coastal domain. During the Early–Middle Chalcolithic, the marine components of everyday life are less apparent, but part-time seafarers still may have been involved in the movement of non-local goods (faience, chlorite) and innovations (lithics, ceramics), at least along the ‘coastscapes’ and rural anchorages of southwestern Cyprus. By the Late Chalcolithic, renewed overseas contacts with the surrounding regions (Anatolia, Crete, the southern Levant) seem evident, not least in the possible export of Cypriot ores. During Prehistoric Bronze Age 1 (mid-late third millennium BC), a regional interaction sphere involving the seaborne movement of metals and metal artefacts between Cyprus, the eastern Aegean and the west coast of Anatolia must have impacted on north coast communities like Vasilia and Lapithos. By Prehistoric Bronze Age 2 (early second millennium BC), documentary evidence reveals that Cypriot copper was being exported via maritime trading ventures to Syria and Babylonia, whilst the number of imports (over 150 found in contemporary cemeteries at Lapithos, Bellapais Vounous and Karmi) escalated noticeably (Webb 2019:79–82; Table 2). As was the case during the Aceramic Neolithic periods, the sea had once again become an important factor in people’s choice of where to live, and marine resources (dentalia, other molluscs) as well as some ‘exotic’ imports (faience, silver and gold jewelry, copper and bronze dress pins) once again appear, at inland sites and coastal centres alike.

Yamasaki’s (2017) study on the relationship amongst the maritime environment, marine resources and the prehistoric communities of Cyprus echoes several points made in the present study, but examines them in an entirely different manner. She too questions the apparent fall-off in transmarine contacts between Cyprus and the surrounding mainland between the LAN and the PreBA, but does so by examining the occurrence or absence of sea-related resources at 43 coastal or near-coastal sites on the island. Using both quantitative and qualitative analyses of tools, fish and shellfish remains, ornamental goods, imports, maritime symbols and technologies, she finds that although there were indeed peaks and troughs in the appearance of these marine-related resources (at their lowest between the fifth to mid-third millennium BC—Yamasaki 2017:57, Fig. 4), maritime contacts never completely ceased. In her view, the data she considered indicate a diachronic link between transmarine contacts and the exploitation of marine resources, technologies and symbolism.

Indeed, on Cyprus the resources of the sea have always formed a typical feature of the island’s broad-spectrum diet (Gomez and Pease 1992:4). And, as Howitt-Marshall (2020) argues in a forthcoming study on maritime connectivity in EAN Cyprus, the material evidence for maritime activity and the exploitation of marine resources suggest that the island’s coasts played a significant economic role throughout Cypriot prehistory. McCartney (2007:89), moreover, noted that Cyprus ‘… is a land where the sea is a part of island life, but where natural harbours are rare, thus interaction and marine resource exploitation may have focused on individual river drainages each with their own outlet to the sea’.

Demesticha’s (2021) recent study of Cypriot coastscapes echoes these views, suggesting that rural anchorages (identified by underwater and coastal survey) likely formed part of Cyprus’s maritime practices and capacities, and represent the exploitation of the island’s coastal zone throughout the long durée of its history and prehistory. As noted in the present study, such anchorages may have existed at EAN Kissonerga Mylouthkia, Neolithic Klepini Troulli (ten kms east of Ayios Epiktitos Vrysi), near the southwest coastal sites of the Chalcolithic (Kissonerga, Lemba Lakkous) and at PreBA Vasilia and Lapithos. Indeed, Peltenburg et al. (2001:77–78) had already suggested that the rocky promontory (Kefalui) just west of the wells at Mylouthkia, which today forms a sheltered cove, could have served as an anchorage for the boats that provided the community’s marine-related needs; such an anchorage serves as an early Holocene example of ‘a persistent Cypriot Aceramic Neolithic tradition: the coastal site … [e.g.] Petra tou Limniti, Troulli I, Akanthou Arkosyko, Cape Greco and Cape Andreas Kastros’.

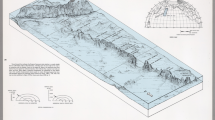

In Demesticha’s view, the island’s maritime geography was determined by the Akrotiri and Karpas peninsulae and by several capes (Kormakiti, Akamas, Kiti, Pyla, Greco) that create sheltered coasts and bays (i.e. with the wind blowing towards them) all around the island. Thus, some of island’s main urban harbours from the Iron Age through the Late Roman period (Marion, Soloi, Kourion, Kition, Salamis-Constantia) were established in the most protected parts of their bays, which provide refuge from westerly winds. Although Cyprus’s coasts have but few deep-water inlets or fully protected bays (Raban 1995:140), the small, rural anchorages identified by Demesticha suggest that the shoreline was once more sinuous, before erosion eliminated small inlets or decimated coastal sites (e.g. Late Bronze Age Maroni Tsaroukkas and Tochni Lakkia on the south coast—Manning et al. 2002; Andreou et al. 2017, 2019) (Fig. 9). Indeed, the location of several major ports (Enkomi/Salamis, Kition-Larnaca, Amathus-Limassol, Kourion-Episkopi, Paphos) along the eastern and southern coasts, the latter exposed to the prevailing and often strong southerly winds, seems to be a continuous feature of Cyprus’s long-term maritime history. As Demesticha (2021) argued: ‘The coast, as the place where people interact with the water, inevitably holds a central role in the processes that shape maritimity and associated behaviours. This is especially true in pre-industrial societies, where it [the coast] was recognized as a natural boundary, a liminal space … imbued with spiritual and cultural associations that demarcated the line between safety and danger or known and unknown …’. In other words, living directly on the coast may not always be seen as advantageous, especially in cases like the exposed south coast of Cyprus, but even there we need to figure into the equation the exploitation of marine resources, the impact of long-distance interaction and occasional or seasonal visits.