Abstract

This study explores the digital self-regulatory practices of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) pre-service teachers via mobile applications in the post-pandemic era. The research is motivated by the need to address the absence of literature on the self-regulatory learning behaviours of EFL pre-service teachers in the aftermath of the pandemic-induced shift to online learning. The study participants were Polish and Turkish EFL students aged between 19 and 23, enrolled at state universities in Poland and Turkey. A validated online survey tool was developed and utilised for data collection based on the piloting phase of the study. The survey employed a combination of multiple-choice and 5-point Likert scale questions to examine participants’ interaction with different types of self-regulated applications after the pandemic. The findings revealed that Duolingo was the most widely used application. This underscored the importance of listening as the most frequently used language skill. The study also revealed a shift in learning patterns among participants following the pandemic as evidenced by the technologies available. Overall, the main findings of this study may serve as significant impetus for further research on pandemic-related changes in digital self-regulated learning practices among EFL learners globally. The results of the study might find broad implications for example for development of a new generation of MOOCs responding various needs of learners as well as incorporating elements of self-regulation into the traditional EFL class to increase its efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a transformation in teaching and learning. In particular, the pandemic heralded a shift from traditional face-to-face teaching to online or distance learning. Teachers and instructors worldwide were required to modify their teaching practices, and to introduce the principles and practices of remote learning (Kılıçkaya et al., 2022). The onset of the pandemic affected students who experienced, on the one hand, exposure to e-learning solutions they were not fully prepared for, and on the other hand, a radical transformation in their learning experiences derived from social isolation, reduced contact with teachers and the closure of educational institutions; moreover, EFL students and teachers faced unique challenges because language learning and teaching requires verbal communication, which was significantly disrupted by the shift to distance learning. Additionally, language learning is a social exercise; consequently, the isolation imposed during the pandemic impeded students’ capacity to practice their foreign language skills (Çıraklı, 2023; Wysocka-Narewska, 2023).

However, it is also important to note that, because foreign language learning requires self-study, the pandemic contributed to the development of different forms of self-directed learning which could at some point replace face-to face activities (Li & Bonk, 2023). Online learning opened up new opportunities for EFL learners, especially in the autonomous use of rich resources (in different formats, developing all skills) available online that can support the learning of a foreign language (Knopf et al., 2021). The access to a variety of online tools and materials to suit personal needs may also enhance students’ motivation to learn and, consequently, boost the efficiency of pedagogical practices (Yu & Zhou, 2022). Online and distance learning also enhances the flexibility of learning, allowing students the opportunity to practice whenever and wherever they choose (Adedoyin & Soykan, 2023). Understood in this way, the shift from traditional face- to-face teaching to distance learning yielded both challenges and opportunities for language learners. This study will investigate the extent to which learners’ self-directed learning practices through online applications have changed as a result of the pandemic, and the challenges and opportunities that this necessarily entails.

Literature review

Self-regulated learning in the digital environment and language learning

Self-regulated learning (SRL) can be defined as taking charge of one’s learning environment by setting goals, managing time and monitoring progress (Lehmann et al., 2014). There are three levels of learner involvement in the self-regulated learning process: metacognitive, behavioural, and motivational (Zimmerman, 2008). Panadero (2017) mentions also emotional/affective aspect. Metacognitive participation enables the constant monitoring and implementation of affordable cognitive strategies (Bai et al., 2020). It relates to learning through enabling the student to reflect upon their learning, to make implicit ideas explicit. Although metacognition does not directly affect second/foreign language learning, metacognition supports understanding various aspects of language development (Zhang & Zhang, 2019), which has been illustrated in the model of Wenden (1999) highlighting the correlation between person, task and strategy in second/foreign language learning, and explains how digital applications support autonomy in learning.

The motivational level is an intrinsically rooted orientation in setting learning goals and planning the steps to achieve them, it supports strongly the development of self-guidance and responsibility in the learning process (Rovers et al., 2019). Self-motivations ensures the volition to perform learning tasks in the future (Panadero, 2017; Pintrich, 2003). Behavioural participation means adapting one’s learning pathway to fit the social and physical environment (Lehmann et al., 2014). Emotional engagement in the task strengthens learning persistence and self-efficacy as well as students’ satisfaction through that correlates with the learners performance (Zhao & Cao, 2023).The three levels of learning demonstrates not only the complex character of SRL, but also its importance for developing responsibility for one’s own learning process, and awareness of one’s own learning styles. Metacognition supports a systematic and critical approach to the learning progress, which is especially important for learning languages (Csizér & Tankó, 2017).

Understood in this way, there can be little doubt that SRL is a multifaceted and complex process, which is comprised of emotional, motivational and cognitive dimensions. Self-regulating practices might be in the future the incentive to optimise and individualize a foreign language learning process adjusting it to the diverse needs and capabilities of students. SRL is an especially important concept to consider in the context of foreign language acquisition and language learning. As is the case in other academic disciplines, self-regulated language learners must plan and monitor their learning process. However, language learners must also develop and monitor specific academic strategies (including grammar, vocabulary, listening, speaking, reading and writing) while at the same time cultivating affective skills and resources (including intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy) (Zhang & Zhang, 2019). As a result, it is crucial to consider the specific strategies that language learners to exercise control over their learning environment. This is an issue which this research study intends to explore in greater depth.

Self-regulated learning in the digital age

Pre-COVID research on e- and online learning focused upon student and teacher perceptions of online teaching within the context of traditional face-to-face teaching practices. The pre-Covid literature focused primarily upon blended learning as a new and interesting, but still largely unknown way of learning, occasionally used as complementary element of regular classes (Žuvic-Butorac et al., 2011), as well as suggestions for using online learning in education with class scenarios (Madani et al., 2019). The use of online tools for autonomous learning, by itself, attracted the attention of many researchers, indicating the beneficial effects of a digital environment on learners’ self-regulated learning (Shih et al., 2010).

Post-pandemic studies, in contrast, highlight the strong relationship between effective learning and self-regulation in emergency online learning contexts, again allowing the presumption that the COVID-forced digital teaching was not without influence on learning habits (Yu & Zhou, 2022). Still, not much is clear about learners’ ways of learning and the influence of the pandemic on that, since the COVID-19 era ended not long ago. Research conducted by Munday (2016) before COVID pandemic combined the use of applications with regular face-to-face classes in the pre-pandemic period, introducing Duolingo as an obligatory element of classroom practice, and assigning 10% of the grade based on application practice. Another study on the use of Duolingo, this time in the pandemic setting, was conducted by Fadda and Alaudan (2020) researching through experiment and comparing learning patterns in two groups. The control group was exposed to traditional online learning combined with face to face meeting in class. In contrast, the experimental group of 40 participants was exposed to the Duolingo application combined with online classes. The researchers found that Duolingo learners remained interested in continuing learning with the application, also after the pandemic, which may indicate that the interventions developed during the pandemic could encourage their use in the post-pandemic environment (Fadda & Alaudan, 2020).

In the pre-pandemic publications, applications are mainly suggested by teachers as a complementary source of knowledge (Munday, 2016). In contrast, in the post-pandemic view, they seem to constitute part of the autonomous learning regulated by EFL learners by themselves (Ahmed et al., 2022). The studies on self-regulated learning discuss different language skills developed by the applications’ users; the difference between pre- and post- pandemic might be noticed in that field. Before the pandemic, vocabulary learning was the focus of self-regulatory practices. In contrast, after the pandemic, EFL learners seem to apply the holistic development of language skills, including grammar and pronunciation. Also, the pandemic contributed to development of more attractive and multimodal exercises on the platforms and offering chat rooms or interaction spaces between users more often (speaking—Alshammary, 2020; vocabulary—Ali & Deris, 2019; grammar—Roy, 2022), good example might be Duolingo, which expanded the offered functions during the pandemic.

In addition to a strong intrinsic motivation resulting from active participating in a technological progress, the possibility of using smartphones, tablets, etc. for foreign language learning, also a strong sense of flexibility in terms of time and place are the main emotional consequences of shifting to online learning. Shift to online means also shift to multimodal, interactive and more international classes since the distance learning enables to chose from the class offer also far from the stable location. Foreign language learning become more available also for adult, working learners. Institutional difficulties, such as the organisation of online classes and hardware problems were a buffer factor, which nevertheless forced the learners to try to learn on their own (Kılıçkaya et al., 2022).

SRL and intercultural differences

Although the number of papers describing ICT user characteristics, as well as their interaction with the latest technology, is increasing there are still many gaps in the literature concerning individual differences between learners (Sukackė, 2019). An et al. (2021) also commented on the lack of investigation of variables such as EFL students’ previous experiences with SRL and their readiness to use online learning environment. Wehmeyer and Zhao (2020) also made the first suggestions about the post-pandemic necessity to shift towards personalised institutional learning, which enables learners to make their own decisions on their learning pathways and is firmly combined with their autonomy and ability to self-regulate development. The study’s main objective was to check whether and how the pandemic had influenced the use of self-regulated learning practices via available digital applications. This paper focuses on studies conducted with young adults studying at universities, which results from the fact that teaching at the tertiary level differs from teaching at lower levels. Pre-service teachers are more metacognitively conscious about their learning because they are also familiar with foreign language teaching theory and methodology (Lofthouse et al., 2021).

Since SRL is a very individual construct, influenced by one’s motivation, it is necessary to identify the factors influencing its efficiency in the post-pandemic era, considering rapid technological advancement and changing conditions on the labour market as well as individual differences between learners, i.e. gender- female learners performing better in online SRL than males that (Liu et al., 2021). Regarding age, the research by Lau (2022) indicates that even secondary learners are not willing to continue self-regulatory practices due to lacking instruction among secondary school learners social class, individual language experience. Also Tsai (2016) analysing the self-regulatory practices of 22–26 year old FL learners, highlights the role of maturity in developing systemacy in learning. In respect to cross-cultural differences the recent research by Xu et al. (2023) among teenagers in Hong Kong, the Republic of Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Scotland, and the US provides interesting insights into the SRL strategies in East Asian and Western countries. The main findings indicate that control strategies are more often used by members of Western cultures where perseverance is more positively correlated with Eastern Asian cultures. However, the authors of the research underline the need of further research in that field. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that only very few studies mention the possibility of behavioural change toward digital SRL among EFL learners after the pandemic in online environment.

Concerning cultural differences Sappor (2022) highlights that cultural changes influence the motivational dimension of SRL and not the cognitive, which might be also the explanation why some cultures adapted more easily to online, self-organised learning than the others. Culture has been a part of “the social fabric of a community, it may play a significant role in the development of SRL skills” (Sappor, 2022, p. 2). Gabryś-Baker (2019) provides interesting insights into the cognitive and affective levels of SRL in Polish-Turkish context stating that Polish learners show strong attachment to socio-psychological aspects of learning environment (affective aspect of SRL) whereas Turkish students were more attached to traditional instructional/ institutionalised approach (cognitive aspect of SRP might play here more important role).

The study aims at filling the research gap by checking the SRL habits in online environment in post-pandemic learning environment in Poland and Türkiye. The choice of the research was strategically conducted in both Poland and Türkiye, considering their distinct geographical and economic characteristics. Which could have an impact on the shaping of EFL learners’ learning behaviour. Moreover, by comparing the learning habits of EFL learners in Poland and Türkiye, especially with the current number of students in higher education exceeding six million students in Türkiye, the outcomes of the study could potentially inform educational practices and policies in other countries facing similar challenges, but with different learning curricula and possibly different learning habits. Additional motivation of choosing the countries was economic and geographical situation, which might give insights into different learning traditions. The multinational perspective allows for a broader understanding of the impact of pandemic-related disruptions on EFL education and provides valuable insights that can be applied in various contexts worldwide. In the study authors concentrated on the identifying of the preferences of participants using applications for digital self-regulated learning as well as stating if self-regulated learning behaviours change during and after the pandemic. Additional value of the bilateral study is defining if there are any significant differences between Polish and Turkish students in implementing digital self-regulated learning. As such, the following research questions were proposed:

-

1.

What are the preferences of participants using applications for digital self-regulated learning?

-

2.

How did self-regulated learning behaviours change during and after the pandemic?

-

3.

Are there any significant differences between Polish and Turkish students in implementing digital self-regulated learning?

Methodology research design

A quantitative research method was adopted for this study in order to explore the pattern between cause and effect (Creswell, 2005; Pallant, 2016), the benefits of which included utilizing statistical analyses to derive results, ensuring a replicable research design and a high degree of internal validity. The choice of a survey within this quantitative framework is rooted in several advantages. First, surveys are relatively straightforward to formulate and distribute, allowing for efficient data collection. Second, they enable the delineation of patterns of cause and effect.

Sampling

The participants of the study were pre-service language teachers specialising in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and Applied Linguistics at Polish and Turkish state universities (Table 1). Convenience sampling was utilised to selected the pre-service teachers who were willing to participate in the study. In total, 206 participants from both countries, Poland and Türkiye, took part in the study. The majority of participants were female, and 28 participants chose not to indicate their gender.

Additionally, the participants’ proficiency in English ranged from B2 and C1. By targeting students from state universities, the study aimed to investigate the experiences and practices of individuals who are undergoing formal education in the field of language and language teaching. Moreover, although the programs have different titles and they may appear distinct on the surface, applied linguistics and language teaching share a common objective: the effective transmission and acquisition of language. Applied linguistics, with its focus on the scientific study of language, provides the theoretical foundation that underpins language teaching. The inclusion of participants from state universities ensures that the study captures the experiences and perspectives of individuals who are actively engaged in language education and have a fundamental understanding of language learning theories and instructional practices.

Data collection instrument and procedure

The survey instrument used in our study was designed based on an extensive review of relevant literature, particularly focusing on digital self-regulated learning practices in language education (Ahmed et al., 2022; Munday, 2016; Tsai, 2016). Initially, a comprehensive review of existing literature on digital self-regulated learning in language teaching was conducted to identify relevant constructs and items. Subsequently, the items were crafted to align with the research objectives and the constructs under investigation. To ensure content validity, the initial draft of the instrument was subjected to a rigorous process of expert review through a panel of experienced researchers and educators in the fields of language education, technology-enhanced learning, and survey methodology. Their expertise contributed to refining the survey items, ensuring they adequately captured the intended constructs. Before administering the survey to the full sample of participants, a pilot test was conducted with w small group of pre-service language teachers (60 participants), who were not included in the main study. This pilot test allowed us to assess the clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of the survey items. Participants in the pilot test were encouraged to provide feedback on item wording and comprehensibility, which helped refine the instrument and contribute to content validity.

The response rate of the survey was 61%, and the responses from the pilot study participants were analysed using appropriate statistical techniques to examine the internal consistency and test- retest reliability of the survey items. The results obtained indicated satisfactory reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeding the recommended threshold of .7. Moreover, for the dichotomous (binary) items in the survey, Kuder–Richardson (K–R) coefficient of equivalence was calculated to assess internal consistency reliability, which was determined to be .80. Finally, the survey was prepared as an online survey using Google Forms. Specifically, a link to the survey was shared by email with current EFL pre-service teachers in the two state universities in Poland and Türkiye, who were recruited to participate in this study. This data collection method was selected as it took minimal time, was not costly, and was uncomplicated, delivering higher response rates.

Data analysis

The responses obtained from the online survey were first saved as raw data, which was imported to IBM SPSS Statistics. For the first three research questions, descriptive statistics were used to determine the frequencies in the responses provided to the questions in the survey. The Chi- Square Test of Independence was calculated for the last research question, to determine the differences between Polish and Turkish students in implementing a digital self-regulated learning approach. The Chi- Square Test of Independence was calculated for the last research question, to determine the differences between Polish and Turkish students in implementing a digital self-regulated learning approach. The Chi-Square Test of Independence was used because only categorical variables can be analysed by this test, which cannot provide any inferences about causation (Pallant, 2016). For the variables of frequency of use of applications, and the participants’ perceptions about the importance of and language improvement by self-regulated learning with applications, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used, to check the normality of the data. The test results indicated significant differences, meaning we cannot accept the null hypothesis and conclude that the data did not come from a normal distribution. Therefore, the Mann–Whitney U Test was used to compare Polish and Turkish students’ frequency of use and attitudes towards SRL.

Results

The survey results on the applications used by the participants are presented in Table 2. While these applications may vary in their specific features, they all contribute to the overall goal of English language acquisition. In total, fourteen applications were examined, and among these, Duolingo was the most widely used app [79.1%]. Duolingo was followed by Quizlet and Cambly, with usage rates of 76.7 and 68.4%, respectively. The application, Wext, had the lowest usage rate [23.8%]. All participants reported using at least one application, and the applications which were mentioned by only one or two participants were excluded from the study.

The results indicated that using social media such as Facebook and Twitter was the most common way for participants to learn about these applications. 62 participants [30.1%] reported that they had discovered these applications through these platforms. Peer recommendations (Friend/classmate) was the second common with 42 participants [20.4%]. Internet advertising was also a significant source of information for 33 participants [16.0%]. In contrast, the least common ways were determined to be through teacher’s recommendation and (online) newspaper/magazine, with only 16 [7.8%] and 17 [8.3%] participants, respectively. Own research was also a relatively uncommon source of information, with 36 participants [17.5%].

The survey also revealed that the participants’ responses on using each language learning application for specific language skills and components varied widely (Table 3). Listening appeared as the most frequently used language skill, with 54 participants using VoScreen, Rosette Stone, and FunEasyLearn for this purpose. Reading appeared as the second frequently used language skill, with 56 participants using Busuu and Rosette Stone. Vocabulary was the third most frequently used language component, and 84 participants reported having used Quizlet, Memrise, and Duolingo for this purpose. In contrast, grammar is the least frequently used skill across all the applications, with only a few participants using it for language learning and practice. Quizlet had the highest percentage of users at 11.2% for practicing grammar, and it was followed by Duolingo at 11.7%. The lowest percentage of users for this skill was observed in HelloTalk and Wext.

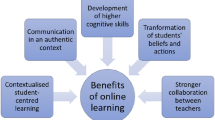

Table 4 presents valuable insights into the benefits of online applications for the self-regulated learning (SRL) of English, as reported by the study participants. The table showcases various aspects of online applications and the percentage of participants who perceived these aspects as beneficial or not. In terms of the flexibility of working on their English when and where they wanted, a significant majority of participants, 176 out of 206 [85.4%], reported that online applications allowed them to do so. Conversely, 30 participants [16.6%] indicated that they did not have this advantage. Regarding access to a wide range of vocabulary and the ability to observe their progress constantly, a substantial portion of the participants, 162 [78.6%], reported experiencing these benefits through online applications. However, 44 participants [21.4%] did not have access to such advantages. Regarding the implementation of a badge system within the application, intended to encourage daily practice, 131 participants [63.6%] expressed that they were motivated by this system. On the other hand, 75 participants [36.4%] did not find the badge system motivating. Participants’ perspectives on the accessibility and interactivity of learning with online applications were also explored. The majority of respondents, 148 [71.8%], agreed that learning became more accessible and interactive with these applications.

However, 58 participants [28.2%] did not share this perception. In terms of memorisation, 138 participants [67.0%] reported that they benefited from the repetition of materials in online applications. Conversely, 68 participants [33.0%] did not observe this advantage. Finally, with regard to learning multiple languages, a considerable proportion of participants, 141 [68.4%], felt that online applications allowed them to learn more languages. However, 65 participants [31.6%] did not have this benefit. The findings from Table 4 indicate that a significant majority of participants found online applications beneficial for their self- regulated learning of English. Specifically, participants highlighted the advantages of flexibility in terms of learning anytime and anywhere, access to a wide range of vocabulary, constant progress monitoring, and the potential for learning multiple languages. These positive perceptions suggest that online applications offer promising opportunities to enhance and support self-regulated learning experiences in the domain of English language acquisition.

Regarding when the participants started using these applications, 52 [25.2%] indicated that they first used the selected activities before the pandemic, while 146 [70.9] stated that they used them during the pandemic. 8 of the participants [3.9%] started to use these applications after the pandemic. Reporting frequency, 74 participants [35.9% of the total] reported using the applications every other day, while 21 [10.2%] reported using them every day. 46 participants [22.3%] reported using applications once a month, and 33 [16.0%] reported using them once a week. Finally, 32 [15.5%] participants reported using applications once every two weeks.

However, in both groups, the mean was 3, indicating a preference for ‘once a week’ use. Regarding the importance of SRL with applications, 12 participants [5.8%] reported that it was not important at all, while 16 [7.8%] reported that it was only slightly important. 40 participants [19.4%] reported that it was essential to some extent, and 103 [50.0%] reported that it was relatively more important. Additionally, 35 participants [17.0%] reported that self-regulated learning with applications was useful. Concerning the contribution of self-regulated learning with applications to language improvement, 10 participants [4.9%] reported that it did not contribute at all, and 26 [12.6%] reported that it only contributed a little. 39 participants [18.9%] reported that it contributed to some extent, and 26 [12.6%] reported that it contributed a lot. Moreover, 39 participants [18.9%] reported that self-regulated learning with applications significantly contributed to language improvement.

The participants were also asked to indicate whether their habits concerning SRL using applications online changed during the pandemic (Table 5). 132 participants [64.1%] indicated so, while 74 participants [35.9%] stated that their habits did not change.

The responses from the participants provide valuable insights into their experiences and perceptions regarding the use of online solutions for language learning. The findings indicate that a majority of respondents agree with certain statements, such as using online solutions more frequently [57.8%] and finding it easier and more convenient to learn through the internet [53.4%]. Furthermore, almost half of the respondents [49.0%] reported that they initiated their language learning journey using online applications. When it comes to enjoyment, less than half of the respondents [44.7%] expressed their agreement with enjoying the use of new applications.

However, it is noteworthy that a considerable proportion of participants [18.0%] agreed that they have become tired of using online applications, highlighting potential fatigue or saturation with these tools. In terms of the benefits derived from using online applications, approximately half of the respondents [51.9%] agreed that memorisation has become more accessible to them through these platforms. Additionally, almost half of the participants [48.1%] indicated that online applications have prevented them from feeling bored during the language learning process. On the other hand, the majority of respondents disagreed with struggling with handwriting [43.7%] and being unable to concentrate on learning [46.6%] while using online applications. These findings shed light on the participants’ perspectives and experiences related to the use of online solutions for language learning. The majority of respondents demonstrated positive attitudes towards the frequency and ease of using online tools for learning, as well as the benefits of enhanced accessibility and prevention of boredom. However, there were also indications of potential challenges, such as fatigue and a lack of concentration, as well as a minority who reported negative attitudes towards enjoyment. Several significant differences were found regarding the applications that the participants know (Table 6). Although the results might seem to be associated with the applications and the participants, these are mainly little to weak associations (the Phi effect value).

As for learning about these applications, there are significant differences with the moderate- level association. While the participants in Poland learn about these applications mainly via (Online) newspapers and magazines, internet advertisements, and social media such as Facebook and Twitter, Turkish participants benefit from their research and social media tools. Fewer participants in both groups indicated teacher’s recommendation (χ2 (1, n = 206) = 29.180, p = .001, phi = .376). As for the time that the participants’ first started using the applications, Polish participants started using them during the pandemic, whereas Turkish participants indicated both before and during the pandemic. Very few participants in both groups selected ‘Before the pandemic’ (χ2 (2, n = 206) = 29.052, p = .001, phi = .376). Moreover, both groups have worked with applications for learning English online during a foreign language class. However, no differences were found regarding the frequency of using these applications (U = 5392, p = .830). Regarding the participants’ perceptions about the importance of language improvement by SRL with applications, no significant differences were found between the two groups of participants (U = 4899, p = .308 for importance, and U = 5451, p = .716 for improvement). Concerning the changes in habits due to the pandemic, both groups indicated a great deal of agreement, indicating several changes concerning SRL using applications online. Online applications offered accessibility, allowing learners to organize their learning, set goals, and monitor progress at their convenience. This flexibility likely garnered agreement as it catered to diverse learning needs. The pandemic also accelerated the integration of technology in education, compelling individuals to familiarize themselves with a myriad of applications that supported SRL. The consensus might reflect the universal adoption of these tools.

There seems to be a lack of substantial age differences among the participants (U = 3685, p = .304). As the ages of both Polish and Turkish learners are proximate and fall within a relatively mature range, this similarity might indicate that age itself may not significantly affect the inclination or willingness to engage in SRL practices. However, gender differences have been identified in the study (U = 2856, p = .002). Female participants, across both Polish and Turkish groups, tend to outperform male participants in online SRL. The inclination of female learners towards utilizing online resources more extensively compared to their male counterparts suggests a gender-based disparity in SRL practices. Regarding cultural differences, the only significant difference was found on the item “Memorising comes easier for me” ((χ2 (2, n = 206) = 10.889, p = .004, phi = .230), which the majority of the Polish students disagreed with. The observation that Turkish learners tend to favour tools enabling memorization suggests a leaning towards knowledge-oriented practices or perhaps an influence from the classroom environment. This preference may indicate a specific approach to learning, emphasizing memorization-based methods, potentially impacting SRL strategies within the Turkish group.

Discussion

The discussion emanating from the findings of the current study outlines a number of issues and considerations that have important implications for language acquisition and pedagogical practices. The initial theme underscores the heightened salience of dimensions within SRL, which is followed by pre and post-pandemic changes and differences in terms of age, gender, and culture.

Dimensions of SRL

The survey conducted a comparative analysis of online tools used for the development of SRL in Poland and Türkiye. One of the aims was to address a gap in the field regarding available tools for SRL, as highlighted by Botero et al. (2021). Among the various tools examined, Duolingo emerged as the most widely utilized application. This predominance was largely attributed to the positive endorsements and recommendations from peers and educators. Close behind Duolingo in terms of usage were Quizlet and Cambly. In a study by Munday (2016), participants stressed the ease of use, practicality, and intuitive features of these applications. However, a significant benefit underscored in this study was the flexibility to access these tools at any time and from any location, potentially signalling a shift in learning patterns, such as initiating their own learning by practicing outside the classroom. This transition from valuing basic functionality to prioritizing the independence of location and time suggests the evolution of learner autonomy and independence in crafting their learning process, as observed by the participants. These benefits during the pandemic could also encourage their use in the post-pandemic environment, which has been indicated by Fadda and Alaudan (2020) and Adedoyin and Soykan (2023). Interestingly, this observation contrasts with the findings of Li and Bonk (2023), who emphasized the predominant use of applications in the initial stages of language learning. For the survey participants, using self-regulatory applications is almost natural, as they had already been accustomed to digital technology. They are eager not only to develop one specific skill (although listening is the most commonly chosen one) but to use these tools to master the language as an entire system, which partially contradicts the results described by Roy (2022). On the basis of these results it might be presumed that the pandemic initially influenced EFL learners’ readiness to work with digital applications and work in a self-regulatory mode, to which they were mainly exposed during the pandemic.

Pre and post-pandemic changes

Most participants started using these apps during the pandemic, but in most cases they continued using them after it, too, appreciating their efficacy. The frequency of app use varied, which confirms the earlier research conducted by Alavi et al. (2022). Turkish students used applications to learn before and during the pandemic, which might be attributed to their enrolment in technology courses in their department, whereas Polish students only started during the pandemic; however, the results indicate that the pandemic was the period of the most intense use of online applications. Social media was the most common source of information for learning about language learning apps, followed by friend/classmate’s recommendations and internet advertisements, which again shows the shift from formal to informal learning, and understanding more willingly self-initiated learning. Additionally, the reliance on recommendations from friends or classmates reflects the impact of peer influence in shaping learners’ decisions. The informal nature of these recommendations implies a trust and reliance on personal connections, indicating that learners are more willing to explore and adopt learning strategies based on the experiences and suggestions of their peers. The participants’ responses varied widely on using each language learning app for different language skills. However, as indicated by other studies (Ali & Deris, 2019; Alshammary, 2020; Roy, 2022), in addition to vocabulary practice, the participants benefited from other skills such as speaking. A few students in both groups only mentioned teacher recommendations regarding similar online tools.

Age, gender, and cultural differences

The findings from this study investigating Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) among Polish and Turkish learners shed light on several key aspects of SRL practices and their relationship with age, gender, and cultural influences. The lack of substantial age differences among the participants suggests that age itself may not significantly impact the inclination or willingness to engage in SRL practices. These findings align resonate with Tsai’s study (2016), emphasizing the role of maturity in developing systemacy in learning, suggesting that maturity rather than age per se plays a role in SRL practices among learners. The significant gender differences within both Polish and Turkish groups, where female participants outperformed male participants in online SRL, echo the findings by Liu et al. (2021), highlighting that female learners tend to perform better in online SRL. This disparity in the utilization of online resources between genders is consistent with the understanding that gender- based differences influence SRL practices.

Some intercultural differences were also observed among the results, with Turkish participants more likely to learn about digital self-regulated applications through their own research and social media, which might have also contributed to self-motivation (Pintrich, 2003). In contrast, Polish participants relied more on online newspapers and magazines, internet advertisements, and social media such as Facebook and Twitter. The results suggest that the tendencies in learning habits among young EFL learners, such as the need for digitalisation, self- control, flexibility and peer impact. Those elements might be an essential indicator of changes in behaviour initiated by the pandemic. The data provides a significant contribution to a new understanding of the pandemic, not only as a time when remote learning was forcibly introduced, but also as a time when learner independence and intellectual curiosity developed, which in turn affected their study habits, which also included the use of online applications in addition to classroom practice (Gabryś-Barker, 2019; Knopf et al., 2021). Due to the constraints of distance learning, students were compelled to assume more responsibility for their education, and explore other avenues for learning. This fresh viewpoint broadens our comprehension of the pandemic as a moment of transformation for learners, not just in terms of adapting to online learning but also in terms of acquiring critical abilities, like self-control, autonomy, and a curiosity-driven approach to learning contexts. The observed preference among Turkish learners for tools enabling memorization, as indicated by the significant difference in the item “Memorising comes easier for me”, showcases a cultural divergence in learning strategies as well as motivational dimension (Sappor, 2022). This aligns with Xu et al.’s research (2023), which highlighted cross-cultural differences in SRL strategies, particularly emphasizing that control strategies are more often used in Western cultures while perseverance is more positively correlated with Eastern Asian cultures. The findings regarding the emphasis on memorization by Turkish learners might suggest a more knowledge-oriented approach or an influence from the classroom environment, potentially impacting their SRL strategies, which was also underlined by Panadero (2017). These results signify the intricate interplay of individual, gender, and cultural factors in shaping SRL practices among Polish and Turkish learners. The alignment with prior research underscores the consistency of certain trends in SRL practices, while the nuances reveal the uniqueness of cultural influences on learning strategies within these specific populations.

Implications

The study also have several implications for educational practices stressing the need for a fundamental shift in educational practices, emphasizing the nurturing of autonomy and curiosity-driven learning, not just as temporary adaptations to crises but as integral components of effective and progressive education systems, which will consider the need for educational institutions to acknowledge and embrace this transformation. This can be done through the inclusion of metacognitive processes where learners an reflect on their own thinking, monitor their understanding, and adapt their strategies. Educational institutions can encourage autonomy by promoting metacognitive awareness, leading learners to take an active role in planning their own learning path as well as assessing their progress. As for motivation, it can be stated that autonomy and curiosity driving learning can be closely connected to learners’ internal motivation. When learners have the freedom to pursue topics of personal interest and the autonomy to have their own learning experiences, intrinsic motivation is also likely to flourish. Moreover, the findings also have implications for learner behaviour. In an environment where autonomy and self-learning are promoted, learners are encouraged to take initiative, make choices, and assume responsibility for their learners.

Conclusion

This study contributes to extending knowledge about digital SRL practices via applications in the post-pandemic era for EFL pre-service teachers in Poland and Türkiye. The results of the study shed new light on how self-regulatory practices, such as using online applications, developed during the forced emergency learning setting and the preferences of the participants using applications. The results also depicted how the habits of regular autonomous learning via applications could become an element of the learning process also once the emergency fully passed, contributing to acquiring critical abilities, like self-control, autonomy, and a curiosity-driven approach to learning. Learning foreign languages via applications is a dynamically developing field, considering the latest trends and benefits offered by the use of new media. The flexibility of use, vocabulary exercises, and constant monitoring of progress were the features that participants of the survey appreciated the most in learning with applications. The study also delivers a pioneering comparison of the different self-regulatory learning applications and their use for developing different skills between Polish and Turkish students in terms of age, gender and cultural differences.

Limitations and further research directions

The limitation of the study is its relatively small sample with the majority being female (206 participants) with different profiles and the distribution of the survey in only two countries. However, this study could be further extended to include gendered dimensions and, in the future, include more participants from other countries. Another topic worth further research is monitoring the further development of the learning patterns acquired during the pandemic. Moreover, the study concentrates on selected applications, checking their efficiency separately. In the future, a comparative analysis of the weaknesses and strengths of more applications supporting self-regulated English learning online could be of interest.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2023). COVID-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(2), 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

Ahmed, A. A. A., Hassan, I., Pallathadka, H., Keezhatta, M. S., Haryadi, R. N., Mashhadani, Z. I. A., Attwan, L. Y., & Rohi, A. (2022). MALL and EFL learners’ speaking: Impacts of Duolingo and WhatsApp applications on speaking accuracy and fluency. Hindawi Education Research International. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6716474

Alavi, S. M., Dashtestani, R., & Mellati, M. (2022). Crisis and changes in learning behaviours: Technology-enhanced assessment in language learning contexts. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(4), 461–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1985977

Ali, A. S. M., & Deris, F. D. (2019). Vocabulary learning through Duolingo mobile application: Teacher acceptance, preferred application features and problems. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering, 8, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.b1017.0982s919

Alshammary, M. S. (2020). The impact of using Cambly on EFL university students’ speaking proficiency. English Language Teaching, 13(8), 12–26. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n8p12

An, Z., Wang, C., Li, S., Gan, Z., & Li, H. (2021). Technology-assisted self-regulated English language learning: Associations with English language self-efficacy, English enjoyment, and learning outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.558466

Bai, B., Wang, J., & Nie, Y. (2020). Self-efficacy, task values and growth mindset: What has the most predictive power for primary school students’ self-regulated learning in English writing and writing competence in an Asian Confucian cultural context? Cambridge Journal of Education, 51(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2020.1778639

Botero, G., Botero Restrepo, M. A., Zhu, C., & Questier, F. (2021). Complementing in-class language learning with voluntary out-of-class MALL. Does training in self-regulation and scaffolding make a difference? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(8), 1013–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1650780

Çıraklı, M. Z. (2023). Reconsidering spatial interaction in the virtual literature classroom after the pandemic lockdown. Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature, 47(3), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.17951/lsmll.2023.47.3.19-29

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (2nd ed.). Merrill Prentice Hall.

Csizér, K., & Tankó, G. (2017). English majors’ self-regulatory control strategy use in academic writing and its relation to L2 motivation. Applied Linguistics, 38(3), 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv033

Fadda, H., & Alaudan, R. M. (2020). Effectiveness of Duolingo app in developing learner’s vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation: A case study of a blended TESOL classroom. International Journal on Emerging Technologies, 11(5), 403–410. https://www.researchtrend.net/ijet/current_issue_ijet.php?taxonomy-id=82#page:6

Gabryś-Barker, D. (2019). Cognitive and affective dimensions of foreign language learning environments: A Polish-Turkish comparative study. Neofilolog, 52(1), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.14746/n.2019.52.1.11

Kılıçkaya, F., Kic-Drgas, J., & Nahlen, R. (2022). The challenges and opportunities of teaching English worldwide in the COVID-19 pandemic. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Knopf, T., Stumpp, S., & Michelis, D. (2021). How online collaborative learning leads to improved online learning experience in higher education. Proceedings of the European Conference on Social Media. https://doi.org/10.34190/ESM.21.010

Lau, K. L. (2022). Exploring achievement-level differences in implementing self-regulated learning instruction in a classical Chinese reading intervention program. Frontiers in Education. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.948650

Lehmann, T., Hähnlein, I., & Ifenthaler, D. (2014). Cognitive, metacognitive and motivational perspectives on preflection in self-regulated online learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.051

Li, Z., & Bonk, C. J. (2023). Self-directed language learning with Duolingo in an out-of-class. Computer Assisted Language Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2023.2206874

Liu, X., He, W., Zhao, L., & Hong, J.-C. (2021). Gender differences in self-regulated online learning during the COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.752131

Lofthouse, R., Greenway, C., Davies, P., Davies, D., & Lundholm, C. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ conceptions of their own learning: Does context make a difference? Research Papers in Education, 36(6), 682–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1767181

Madani, Y., Erritali, M., Bengourram, J., & Sailhan, F. (2019). Social collaborative filtering approach for recommending courses in an E-learning platform. Procedia Computer Science, 151, 1164–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.04.166

Munday, P. (2016). Duolingo como parte del curriculum de las clases de lengua extranjera [The case for using DUOLINGO as part of the language classroom experience]. Linguistics, 19(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.5944/RIED.19.1.14581

Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS (6th ed.). Open University Press/McGraw-Hill.

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 667–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.667

Rovers, S. F. E., Clarebout, G., & Savelberg, H. H. (2019). Granularity matters: Comparing different ways of measuring self-regulated learning. Metacognition Learning, 14, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-019-09188-6

Roy, M. (2022). The use of smartphone applications for students to learn ESL grammar and vocabulary. Culminating Projects in Information Media, 42, 1. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1043&context=im_etds

Sappor, G. (2022). The influence of culture on the development and organisation of self-regulated learning skills. Journal of Psychology & Behavior Research, 4(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.22158/jpbr.v4n2p1

Shih, K. P., Chen, H. C., Chang, C. Y., & Kao, T. C. (2010). The development and implementation of scaffolding-based self-regulated learning system for e/m-learning. Educational Technology & Society, 13(1), 80–93. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/75236/

Sukackė, V. (2019). Towards extending the original technology acceptance model (TAM) for a better understanding of a better understanding of educational technology adoption. Society, Integration, Education: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, 5, 525–549. https://doi.org/10.17770/sie2019vol5.3798

Tsai, C. C. (2016). The role of Duolingo on foreign language learners’ autonomous learning. The Asian conference of language learning 2016: Official conference of proceedings. https://papers.iafor.org/wp-content/uploads/papers/acll2016/ACLL2016_26504.pdf

Wehmeyer, M., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Teaching students to become self-determined learners. ASCD.

Wenden, A. L. (1999). An introduction to metacognitive knowledge and beliefs in language learning: Beyond the basics. System, 27(4), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00043-3

Wysocka-Narewska, M. (2023). To study or not to study online? Students’ views on distance education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A diary study. Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature, 47(3), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.17951/lsmll.2023.47.3.7-18

Xu, K. M., Cunha-Harvey, A. R., King, R. B., de Koning, R. B., Paas, F., Baars, M., Zhang, J., & de Groot, R. (2023). A cross-cultural investigation on perseverance, self-regulated learning, motivation, and achievement. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 53(3), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2021.1922270

Yu, H., & Zhou, J. (2022). Social support and online self-regulated learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pacific Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2022.2122021

Zhang, D., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Metacognition and self-regulated learning (SRL) in second/foreign language teaching. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 883–897). Springer.

Zhao, S., & Cao, C. (2023). Exploring relationship among self-regulated learning, self-efficacy and engagement in blended collaborative context. SAGE Open.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312909

Žuvic-Butorac, M., Roncevic, N., Nemcanin, D., & Nebic, Z. (2011). Blended e-learning in higher education: Research on students’ perspective. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 8, 409–429. https://doi.org/10.28945/1427

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kic-Drgas, J., Kılıçkaya, F. Exploring novel approaches to digital self-regulated learning: a study on the use of mobile applications among Polish and Turkish EFL pre-service teachers. Education Tech Research Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10374-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10374-w