Abstract

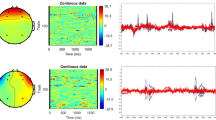

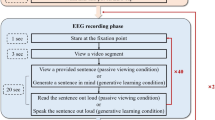

Much effort has been put into the design of video lectures, but little attention has been paid to the social environment in which learning takes place. The present study addressed this gap by assigning Chinese undergraduate and graduate students who had passed the College English Test-4 to learn easy or difficult English vocabulary words in three different conditions: alone, in the presence of a peer spectator, or in the presence of a peer co-actor. In Experiment 1, participants learned difficult vocabulary words and the effects were measured by both neural activity (EEG signals, measured while participants watched the video lectures and during the generative learning activities) and behavioral evidence (learning performance assessed after having watched the video lectures: immediate and delayed test scores, cognitive load, and motivation). Repeated measures ANOVAs showed that learning alone was more beneficial than learning in the presence of a peer, as indicated by better learning performance and reduced EEG theta band power. In Experiment 2, participants learned easy (rather than difficult) English vocabulary words and outcomes were measured by immediate and delayed learning performance. Repeated measures ANOVAs showed that the presence of a peer was more beneficial than learning easy content alone. Combined data from both experiments showed that difficulty moderated the effect of social context. Participants performed best when students learned the difficult content alone, and when they learned the easy content with a peer present.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Aiello, J. R., & Kolb, K. J. (1995). Electronic performance monitoring and social context: Impact on productivity and stress. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(3), 339–353.

Antonenko, P. D., & Niederhauser, D. S. (2010). The influence of leads on cognitive load and learning in a hypertext environment. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 140–150.

Aparicio, M., Bacao, F., & Oliveira, T. (2016). Cultural impacts on e-learning systems’ success. The Internet and Higher Education, 31, 58–70.

Baron, R. S., Moor, D., & Sanders, G. S. (1978). Distraction as a source of drive in social facilitation research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 816–824.

Belletier, C., Normand, A., & Huguet, P. (2019). Social-facilitation-and-impairment effects: From motivation to cognition and the social brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(3), 260–265.

Brand, S., Reimer, T., & Opwis, K. (2003). Effects of metacognitive thinking and knowledge acquisition in dyads on individual problem solving and transfer performance. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 62(4), 251–261.

Burwitz, L., & Newell, K. M. (1972). The effects of the mere presence of coactors on learning a motor skill. Journal of Motor Behavior, 4(2), 99–102.

Caspar, A., Charlotte, F., Lenka, L., & Sarah, R. (2018). Social facilitation of laughter and smiles in preschool children. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1048.

Castro-Meneses, L. J., Kruger, J. L., & Doherty, S. (2020). Validating theta power as an objective measure of cognitive load in educational video. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68, 181–202.

Cierniak, G., Scheiter, K., & Gerjets, P. (2009). Explaining the split-attention effect: Is the reduction of extraneous cognitive load accompanied by an increase in germane cognitive load? Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 315–324.

Claypoole, V. L., & Szalma, J. L. (2019). Electronic Performance Monitoring and sustained attention: Social facilitation for modern applications. Computers in Human Behavior, 94, 25–34.

Cottrell, N. B. (1968). Performance in the presence of other human beings: Mere presence and affiliation effects. In E. C. Simmel, R. A. Hoppe, & G. A. Milton (Eds.), Social facilitation and imitative behavior (pp. 91–110). Allyn and Bacon.

Cottrell, N. B. (1972). Social facilitation. In C. G. McClintock (Ed.), Experimental social psychology (pp. 185–236). Holt.

Czeszumski, A., Montecinos, E. A. L., Carrera, C., Aumeistere, A., Xavier, A., Wahn, B., & König, P. (2011). Learned knowledge about the co-actor’s behavior influences performance in a joint visuomotor task. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 54, 59–101.

de Bruijn, E. R. A., Miedl, S. F., & Bekkering, H. (2011). How a co-actor’s task affects monitoring of own errors: Evidence from a social event-related potential study. Experimental Brain Research, 211, 397–404.

DeLeeuw, K. E., & Mayer, R. E. (2008). A comparison of three measures of cognitive load: Evidence for separable measures of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane load. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(1), 223.

Dion, K. K., & Berscheid, E. (1974). Physical attractiveness and peer perception among children. Sociometry, 37(1), 1–12.

Dönmez, O., Akbulut, Y., Telli, E., Kaptan, M., Özdemir, İ. H., & Erdem, M. (2022). In search of a measure to address different sources of cognitive load in computer-based learning environments. Education and Information Technologies, 27(7), 10013–10034.

Dunand, M., Berkowitz, L., & Leyens, J.-P. (1984). Audience effects when viewing aggressive movies. British Journal of Social Psychology, 23(1), 69–76.

Finnigan, S., O’Connell, R. G., Cummins, T. D., Broughton, M., & Robertson, I. H. (2011). ERP measures indicate both attention and working memory encoding decrements in aging. Psychophysiology, 48(5), 601–611.

Grey, S., Cosgrove, A. L., & van Hell, J. G. (2020). Faces with foreign accents: An event-related potential study of accented sentence comprehension. Neuropsychologia, 147, 107575.

Hinchcliffe, C., Jiménez-Ortega, L., Muoz, F., Hernández-Gutiérrez, D., Casado, P., Sanchez-García, J., & Martín-Loeches, M. (2020). Language comprehension in the social brain: Electrophysiological brain signals of social presence effects during syntactic and semantic sentence processing. Cortex, 130, 413–425.

Hong, J. Z., Heikkinen, J., & Blomqvist, K. (2010). Culture and knowledge co-creation in R&D collaboration between MNCs and Chinese universities. Knowledge and Process Management, 17, 62–73.

Horovitz, T., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). Learning with human and virtual instructors who display happy or bored emotions in video lectures. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106724.

Hsieh, Y. (2020). Effects of video captioning on EFL vocabulary learning and listening comprehension. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(5–6), 567–589.

Hunt, P. J., & Hillery, J. M. (1973). Social facilitation in a coaction setting: An examination of the effects over learning trials. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9(6), 563–571.

Iwaniec, J. (2019). Language learning motivation and gender: The case of Poland. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 29(1), 130–143.

Jacob, L., Lachner, A., & Scheiter, K. (2022). Do school students’ academic self-concept and prior knowledge constrain the effectiveness of generating technology-mediated explanations? Computers and Education, 182, 104469.

Jahng, J., Kralik, J. D., Hwang, D. U., & Jeong, J. (2017). Neural dynamics of two players when using nonverbal cues to gauge intentions to cooperate during the Prisoner’s Dilemma Game. NeuroImage, 157, 263–274.

Jensen, O., Gelfand, J., Kounios, J., & Lisman, J. E. (2002). Oscillations in the alpha band (9–12 Hz) increase with memory load during retention in a short-term memory task. Cerebral Cortex, 12(8), 877–882.

Jensen, O., & Tesche, C. D. (2002). Frontal theta activity in humans increases with memory load in a working memory task. European Journal of Neuroscience, 15(8), 1395–1399.

Jiseon, S., Hyunjoo, L., Eunsun, A., & Young Woo, S. (2020). Effects of interaction between social comparison and state goal orientation on task performance. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 48(3), 1–12.

Joy, S., & Kolb, D. A. (2009). Are there cultural differences in learning style? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(1), 69–85.

Kamiński, J., Brzezicka, A., Gola, M., & Wróbel, A. (2012). Beta band oscillations engagement in human alertness process. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 85(1), 125–128.

Khader, P. H., Jost, K., Ranganath, C., & Rösler, F. (2010). Theta and alpha oscillations during working-memory maintenance predict successful long-term memory encoding. Neuroscience Letters, 468(3), 339–343.

Khader, P., Ranganath, C., Seemuller, A., & Rosler, F. (2007). Working memory maintenance contributes to long-term memory formation: Evidence from slow event-related brain potentials. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 212–224.

Klimesch, W., Schack, B., & Sauseng, P. (2005). The functional significance of theta and upper alpha oscillations. Experimental Psychology, 52(2), 99.

Korbach, A., Brünken, R., & Park, B. (2017). Measurement of cognitive load in multimedia learning: A comparison of different objective measures. Instructional Science, 45(4), 515–536.

Kosch, T., Karolus, J., Zagermann, J., Reiterer, H., Schmidt, A., & Woźniak, P. W. (2023). A survey on measuring cognitive workload in human-computer interaction. ACM Computing Surveys. https://doi.org/10.1145/3582272

Krieglstein, F., Beege, M., Rey, G. D., Sanchez-Stockhammer, C., & Schneider, S. (2023). Development and validation of a theory-based questionnaire to measure different types of cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1), 9.

Kruger, J. L., & Doherty, S. (2016). Measuring cognitive load in the presence of educational video: Towards a multimodal methodology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(6), 19–31.

Leppink, J., Paas, F., Van der Vleuten, C. P., Van Gog, T., & Van Merriënboer, J. J. (2013). Development of an instrument for measuring different types of cognitive load. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 1058–1072.

Lin, L., Ginns, P., Wang, T., & Zhang, P. (2020). Using a pedagogical agent to deliver conversational style instruction: What benefits can you obtain? Computers and Education, 143, 103658.

Liu, N., & Yu, R. (2018). Determining effects of virtually and physically present co-actor in evoking social facilitation. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries, 28(5), 260–267.

Liu, N., Yu, R., Yang, L., & Lin, X. (2017). Gender composition mediates social facilitation effect in co-action condition. Scientific Reports, 7, 15073.

Lytle, S. R., Garcia-Sierra, A., & Kuhl, P. K. (2018). Two are better than one: Infant language learning from video improves in the presence of peers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA, 115(40), 9859–9866.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43–52.

Mayer, R. E., Sobko, K., & Mautone, P. D. (2003). Social cues in multimedia learning: Role of speaker’s voice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 419.

Meumann, E. (1925). Haus- und Schularbeit. Experimente an Kindern der Volksschule. Julius Klinkhardt.

Montero Pérez, M., Peters, E., & Desmet, P. (2018). Vocabulary learning through viewing video: The effect of two enhancement techniques. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(1–2), 1–26.

Moser, R. S., Schatz, P., Neidzwski, K., & Ott, S. D. (2011). Group versus individual administration affects baseline neurocognitive test performance. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(11), 2325–2330.

Nunnally, J. C., & Berstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McCraw-Hill, Inc.

Örün, Ö., & Akbulut, Y. (2019). Effect of multitasking, physical environment and electroencephalography use on cognitive load and retention. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 216–229.

Paas, F. G. (1992). Training strategies for attaining transfer of problem-solving skill in statistics: A cognitive-load approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 429.

Paas, F. G., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2004). Cognitive load theory: Instructional implications of the interaction between information structures and cognitive architecture. Instructional Science, 32(1/2), 1–8.

Pi, Z., & Hong, J. (2016). Learning process and learning outcomes of video podcasts including the instructor and PPT slides: A Chinese case. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 53(2), 135–144.

Pi, Z., Liu, C., Meng, Q., & Yang, J. (2022). Co-learner presence and praise alters the effects of learner-generated explanation on learning from video lectures. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 1–20.

Pi, Z., Liu, X., & Yang, J. (2021c). The impacts of social comparison on learners’ visual attention and learning performance in video lectures. E-education Research, 09, 56–61+83 (in Chinese).

Pi, Z., Xu, K., Liu, C., & Yang, J. (2020). Instructor presence in video lectures: Eye gaze matters, but not body orientation. Computers and Education, 144, 103713.

Pi, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhou, W., Xu, K., Chen, Y., Yang, J., & Zhao, Q. (2021c). Learning by explaining to oneself and a peer enhances learners’ theta and alpha oscillations while watching video lectures. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(2), 659–679.

Pi, Z., Zhu, F., Zhang, Y., & Yang, J. (2021b). An instructor’s beat gestures facilitate second language vocabulary learning from instructional videos: Behavioral and neural evidence. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211039023. Advance Online Publication.

Plass, J. L., Heidig, S., Hayward, E. O., Homer, B. D., & Um, E. (2014). Emotional design in multimedia learning: Effects of shape and color on affect and learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 128–140.

Rader, S. B. E. W., Henriksen, A. H., Butrymovich, V., Sander, M., Jorgensen, E., Lonn, L., & Ringsted, C. V. (2014). A study of the effect of dyad practice versus that of individual practice on simulation-based complex skills learning and of student’ perceptions of how and why dyad practice contributes to learning. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1287–1294.

Rueschemeyer, S. A., Gardner, T., & Stoner, C. (2015). The Social N400 effect: How the presence of other listeners affects language comprehension. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 22, 128–134.

Sauseng, P., Griesmayr, B., Freunberger, R., & Klimesch, W. (2010). Control mechanisms in working memory: A possible function of EEG theta oscillations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(7), 1015–1022.

Sawyer, D. T., & Noel, F. J. (2000). Effect of an audience on learning a novel motor skill. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 91(2), 539–545.

Scharinger, C., Soutschek, A., Schubert, T., & Gerjets, P. (2015). When flanker meets the n-back: What EEG and pupil dilation data reveal about the interplay between the two central-executive working memory functions inhibition and updating. Psychophysiology, 52(10), 1293–1304.

Skouteris, H., & Kelly, L. (2006). Repeated-viewing and co-viewing of an animated video: An examination of factors that impact on young children’s comprehension of video content. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 31(3), 22–30.

Skuballa, I. T., Xu, K. M., & Jarodzka, H. (2019). The impact of co-actors on cognitive load: When the mere presence of others makes learning more difficult. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 30–41.

Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 22(2), 123–138.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Measuring cognitive load. In Cognitive load theory (pp. 71–85). Springer.

Szymanski, C., Pesquita, A., Brennan, A. A., Perdikis, D., Enns, J. T., Brick, T. R., et al. (2017). Teams on the same wavelength perform better: Inter-brain phase synchronization constitutes a neural substrate for social facilitation. NeuroImage, 152, 425–436.

Tercanlioglu, L. (2004). Exploring gender effect on adult foreign language learning strategies. Issues in Educational Research, 14(2), 181–193.

Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American Journal of Psychology, 9, 507–533.

Uziel, L. (2007). Individual differences in the social facilitation effect: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(3), 579–601.

Wang, J., Antonenko, P., Keil, A., & Dawson, K. (2020). Converging subjective and psychophysiological measures of cognitive lad to study the effects of instructor-present video. Mind, Brain, and Education, 14(3), 279–291.

Wróbel, A. (2000). Beta activity: A carrier for visual attention. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis, 60(2), 247–260.

Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149, 269–274.

Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Compresence. In P. B. Paulus (Ed.), Psychology of group influence (pp. 35–60). Erlbaum.

Zhang, J., Gao, M., & Zhang, J. (2021). The learning behaviours of dropouts in MOOCs: A collective attention network perspective. Computers and Education, 167, 104189.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (62007023; 62177027); the Research Projects of Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China under Grant (19YJC190007); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2022ZYZD04); and the Research Program Funds of the Collaborative Innovation Center of Assessment toward Basic Education Quality at Beijing Normal University under Grant (2022-05-057-BZPK01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. YZ: Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization. QY: Software, Investigation, Methodology. JY: Supervision, Funding Acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest, as we conducted this study only as part of our research program.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Artificial Intelligence in Education at Central China Normal University.

Informed consent

The participants were volunteers who provided written informed consent. They were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Confidentiality was ensured by using numbers instead of names in the research data base. Data were only used for research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pi, Z., Zhang, Y., Yu, Q. et al. Difficulty level moderates the effects of another’s presence as spectator or co-actor on learning from video lectures. Education Tech Research Dev 71, 1887–1915 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10256-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10256-7