Abstract

Preparing students for professional life in a Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous twenty-first century world has seen tertiary institutions eschew the traditional ‘lecture-tutorial’ model in favour of active learning approaches. However, implementing these approaches is not unproblematic. This paper explores how we navigated the tensions of cultivating twenty-first century skills in our students—first-year preservice teachers—through a purposely designed approach to active learning in an educational technology course. We illustrate how deploying Bakhtinian precepts through reflexive inquiry supported sensemaking of discomfort, leveraging this sensemaking to reinvigorate practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Contemporary tertiary institutions are expected to prepare students for professional life in a Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous (VUCA) world (Leblanc, 2018). Developing students’ twenty-first century skills is regarded as key to achieving this goal (Chai & Kong, 2017; Davies et al., 2011), and even as a moral obligation (Kivunja, 2014). While terms are often used interchangeably and inconsistently (Gordon et al., 2009; OECD, 2005), some examples of twenty-first century skills include creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, initiative, empathy, and cognitive flexibility (World Economic Forum, 2020). The capacity to deploy technology to leverage these skills to be more competitive in the contemporary global economy is also regarded as essential (Valtonen et al., 2017). In teacher education, there is arguably a particularly compelling argument for cultivating twenty-first century skills: graduate teachers are themselves responsible for cultivating such skills in their own school students. The Australian Curriculum embeds seven General Capabilities across all learning areas from Foundation to Year 10, which “closely approximate what are referred to as twenty-first century skills or competencies” (Care et al., 2014, p. 185). For example, Critical and Creative Thinking, Digital Literacy, and Personal and Social Capability (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], (2022).

Because contemporary learners are being prepared for a profoundly different world to that of previous generations, approaches to teaching and learning have necessarily evolved (Nissim et al., 2016). In higher education generally, and teacher education specifically, practice has shifted away from traditional, transmissive approaches to embrace active learning (AL) approaches that are often technology rich. Synthesising Bonwell and Eison’s (1991) original definition with subsequent scholarly understandings of AL, Mizokami (2018) defines active learning as, “all kinds of learning beyond the mere one-way transmission of knowledge in lecture-style classes (= passive learning). It requires engagement in activities (writing, discussion, and presentation) and externalizing cognitive processes in the activities” (p. 79).

Research indicates that AL can improve engagement and academic outcomes (Davidson, 2017), and prepare students for twenty-first century life by cultivating more flexible and adaptable learners (Brewer & Movahedazarhouligh, 2018). Despite these potential benefits in embracing AL, particularly in technology-rich environments, Tharayil et al. (2018) have identified recurring student resistance to AL. Finelli et al. (2018), have even gone to the extent of identifying specific modes of overcoming obstacles to AL enactment. Moreover, Matsushita (2018) suggests that active learning can cultivate passive attitudes towards learning and disaffect learners who prefer to learn alone. Hwang et al. (2018) argue that implementing AL, particularly in technology-rich environments, often leaves students “confused and frustrated” (p. 451). Dall’Alba and Bengsten (2019) argue that active learning has not received sufficient critical interrogation, and that AL research and practice largely conceives learning narrowly as something that “can be detected and rigorously measured” (Dall’Alba & Bengsten, 2019, p. 1478). Further, AL does not guarantee improved learning outcomes, but can be unsettling, confusing, and even evoke a temporary sense of incompetence in the learner (Dall’Alba & Bengsten, 2019). Our experience reflects these diverse scholarly perspectives—we grappled with such tensions in deploying course experiences that deploy AL approaches in response to twenty-first century educational imperatives around ‘best practice’ while simultaneously managing student confusion, frustration, and anxiety evoked by these same approaches.

In our case, we used specifically selected AL approaches to support our students, first-year preservice teachers (PSTs), to develop twenty-first century skills so they could, in turn, develop these skills in their own students. However, we were often surprised by our students’ resistance and anxieties and found this to be a recurring topic of conversation in our formal and informal team meetings. This paper grew from these conversations, as we sought to make sense of the struggles we encountered teaching into this course by formalising our professional conversations as deliberate reflexive inquiry. We capture the various forms of discomfort we experienced through autobiographical ‘snapshots’, which are then analysed by drawing on Bakhtinian concepts of dialogue, ideological becoming, and chronotope. In this way, we explore how our professional conversations helped us conceive discomfort as critical to human development, make sense of the emotions evoked by failure, and leverage this sensemaking to reinvigorate our practice.

To achieve our aims, we first outline the Bakhtinian precepts deployed in our professional conversations and in analysis and discussion of those conversations. We then provide our research context by describing the course around which our conversations centred and outlining our methodology. Finally, we share and discuss our reflexive ‘snapshots’ of teaching into the course before summarising the value of this contribution to the field, including possibilities for future research.

Theoretical foundations

Contemporary higher education conceives learners not as passive receptacles but as active participants in the construction of knowledge (Nissim et al., 2016)—a shift demanding approaches to teaching and learning which often challenge “traditional hierarchical teacher-student relations” (p. 29). A sociocultural perspective (e.g., Penuel & Wertsch, 1995; Vygotsky, 1978) can help us appreciate the implications of contemporary educational contexts through a conception of learning as social rather than isolated; situated in a particular social, historical, and/or institutional contexts; mediated by tools such as language; and, in recent decades, as involving changes in selfhood and not just cognitive development (Wortham, 2006, p. 25).

While links between learning (knowing) and identity (being) have long been acknowledged (Wortham, 2006) including by Vygotsky (1934/1987), these connections have only been more fully explored in recent decades (Dall’Alba, 2009; Dall’Alba & Barnacle, 2007). Matusov (2007) argues that Bakhtinian theory offers valuable ways of understanding learning more holistically, beyond instrumental measurements of knowledge and skill—not just as human development but human being (Renshaw, 2004). Of Bakhtin’s many precepts, often grouped under the overarching term, ‘dialogism’ (Holquist, 1990), ideological becoming (Bakhtin/Medvedev, 1978) is of interest in this research. ‘Ideological becoming’ is a term that captures how we, as teacher educators, developed ideological perspectives that helped us navigate the tensions evoked by AL pedagogies in the context of the educational technology course we designed.

Ideological becoming is social, occurring in ideological environments or ‘contact zones’ (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 14; Freedman & Ball, 2004). Classrooms are rich contact zones where students and teachers encounter diverse points of view. These points of view comprise two types: authoritative and internally persuasive discourses. Authoritative discourse is assumed to be ‘true’, “either because it has been passed down through time as traditional knowledge, is asserted through available science, or governs our thinking through religious, political, or economic doctrine” (Gomez et al., 2015, p. 163). In contrast to the authoritatively ‘true’ “word of the fathers” (Bakhtin, 1981, pp. 342–343), internally persuasive discourse is that regarded by an individual as personally convincing. Unlike authoritative discourse, internally persuasive discourse is neither imposed nor fixed but changeable and develops through dynamic interaction with other discourses in different contexts (Bakhtin, 1981).

In classroom contact zones, teachers and students, “learn to navigate and negotiate various discourses, positions, and degrees of authority” (Fecho & Clinton, 2016, p. 54), and thereby determine which discourses are internally persuasive for each individual. Navigating and negotiating different perspectives, however, is not easy but involves “an intense struggle within us for hegemony among various available verbal and ideological points of view, approaches, directions, and values” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 346). For both students and teachers, tension and struggle are therefore not stumbling blocks to ideological becoming but a necessary and healthy element of it. The important role of struggle is also evident in Bakhtin’s concept of the chronotope—the time–space contexts for an individual’s developing ideologies.

A chronotope is “like a lens that may be used in relation to personal or literary narratives to create and critique the meaning of prior, anticipated, and present events in an extended time–space, such as teaching and learning in a classroom” (Edmiston, 2016, p. 337). For example, in our conversations about the experience of teaching into the course under scrutiny, we have invoked shared and individual chronotopic ‘chunks of history’ (Blommaert, 2010) to position ourselves both in relation to the past experience of teaching into this course which ‘anchors’ our perspective, and to the present (Blackledge & Creese, 2017). Chronotopes develop over time as we ‘imagine, enact and contest’ (Brown & Renshaw, 2006) other chronotopes through dialogue within ourselves and with other people to generate ‘hybrid’ chronotopes (Brown & Renshaw, 2006).

Drawing on these Bakhtinian concepts in our professional conversations helped us make sense of the discomforts and struggles we experienced teaching this course. We outline the research context and methods in the following section, then focus on how these theoretical precepts supported our collective sensemaking processes, helping us to reconceive discomfort and struggle as important mechanisms for our professional ideological becoming or development (Edmiston, 2016).

Research context

This research has its origins in the Active Learning Pathways Project (ALPP) (The University of Queensland, 2017–2018). The aim of the ALPP was to “increase the uptake of active learning approaches within and across schools in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences [HASS]” (The University of Queensland, 2017–2018)—a goal that arguably reflects the broader shift to AL in higher education generally. Our research project was one of 11 in the HASS faculty under the umbrella of the larger ALPP; each project explored different AL approaches appropriate to the specific course or context. We deployed AL approaches to support first-year preservice teachers (PSTs) to develop twenty-first century skills so they could, in turn, develop these skills in their own students.

Our involvement in the ALPP unfolded, serendipitously, from being asked to collaboratively redesign a first-year education course focusing on technology for teaching and learning. We were encouraged by the Head of School at the time to take risks and be innovative, even if we “fell flat on our faces”—a daunting but exciting brief that marked the beginning of many professional conversations. The redesigned course followed five design principles that embedded AL strategies in curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment:

-

(1)

Flipped learning: Three out of four weekly face-to-face lectures were replaced with online lectures delivered asynchronously through short videos. Lasting no longer than ten minutes, videos were designed to: provide an overview of the field relevant to that week’s learning, including competing perspectives, so students had an 'entry point’ to the assigned readings; make clear and explicit connections to course design and classroom practice; and provoke critical reflection on and problematisation of course content. In these ways, we sought to prepare PSTs to engage in the tutorials (outlined below) and empower them to reflect on their own ‘practical theories’ and hopefully, support them to bridge the ‘theory practice divide’ that often dogs teacher education (Smagorinsky et al., 2003).

-

(2)

Course staff as critical friends: Rather than being ‘experts’ who explicitly taught students how to use various digital tools, tutors became co-explorers with students. This supported the AL strategy of peer learning, often deployed in higher education to enhance teaching and learning with and about technology (Coorey, 2016).

-

(3)

Cyclical tutorials linked to assessment: Tutorials followed a three-wave ‘Sandpit–Synergy–Showcase’ structure. First, students collaboratively played in the ‘sandpit’ with unfamiliar digital tools they would use to create their digital artefacts for assessment. In Synergy, students shared their works-in-progress, giving and receiving constructive feedback to improve their artefacts. In Showcase, each group presented their final digital product, improved based on critical feedback and reflection. Tutorials thus reflected the AL strategy of learner-centred experiential learning (Misseyanni et al., 2018).

-

(4)

Group assessment: For three of the four assessment tasks, students worked in the same, self-selected small groups, and received a group mark to encourage shared and equal responsibility for contributions and mimic collaborative teacher practices.

-

(5)

Critical reflection: This was formally captured in the fourth individual task but was also an explicit element of the Synergy tutorials.

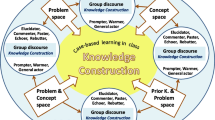

These design principles, underpinned by AL strategies that required students to ‘do things’ and then reflect on what they are doing (Misseyanni et al., 2018) scaffolded the development of four, key twenty-first century student competencies: curation (Bearden, 2016), collaboration, creation, and critical reflection (Germaine et al., 2016). We sought to immerse PSTs in experiences that reflect the technology rich, VUCA professional world they will inhabit as graduate teachers and, hopefully, support them to cultivate twenty-first century skills in their own future school students.

Role of researchers

In 2017, the first and third author (course co-ordinators) shared lecturing responsibilities, both face-to-face and several short learning videos, discussed shortly. Seven course tutors, including the second author, contributed the remaining short videos in accordance with their areas of expertise (e.g., digital storytelling; self-efficacy). All course staff taught into one or two tutorials, comprising approximately 20 students in each group (approximately 270 students in total). In 2018, the first author did not teach into the course but remained involved in analysing course data as part of the ALPP. The second and third authors taught into the course as lead tutor and course coordinator respectively and there were six course tutors in total, including the second and third author, and approximately 300 students in total. One aspect of the ALPP and the present paper involves exploring how our professional conversations supported sensemaking of the Student Evaluation of Teaching (SET) data, which we had found unsettling, both in relation to the course as a whole and individual tutorials.

We were aware of scholarly support for and critique of the effectiveness of AL approaches such as those we deployed, and we were not expecting the redesigned course to be a ‘magic bullet’ to achieve high levels of student satisfaction in the SET data. But we were surprised by the nature and extent of the discomfort we noticed within ourselves and in our PSTs, both during the course and later when interrogating the SET data. Through the action research framework of the ALPP, we drew on and shared theoretical perspectives in our conversations to help us make sense of tensions and confusion, drawing on the first author’s research interest in the work of Mikhail Bakhtin.

Data

As the present paper emerged from the ALPP, we first outline the data we analysed in relation to that project and then describe the data corpus that we drew on in this paper specifically.

Active Learning Pathways Project (ALPP) data

As outlined earlier, as part of the ALPP we deployed AL to create an environment in which our students—first year preservice teachers (PSTs)—developed their twenty-first century skills so they were better equipped to develop these skills in their own future school students. To investigate the extent to which we achieved this, we interrogated quantitative and qualitative student evaluation of teaching (SET) data generated in response to the 2017 and 2018 iterations of the course. There were approximately 260 first-year education students enrolled in both 2017 and 2018. In 2017, there were 105 student respondents to the SET survey, while in 2018 there were 70 respondents.

We also analysed a sample (n = 21) of students’ final assessment tasks, in which they critically reflected on how their perception of technology-enhanced teaching and learning had evolved (or not) during the course. These were students who consented to participate as part of the ALPP project. Finally, we generated data through dialogues and documentation of teaching staff reflections on SET data and the experience of teaching into the course. We have reported on these data elsewhere (McLay & Reyes, 2019a, 2019b; Reyes et al., 2021).

Method: reflexive inquiry

The present paper emerged from the ALPP through our conversations in relation to the SET data and our experience teaching into the course. These conversations were initially organic, but as we noticed our shared sense of confusion and discomfort in relation to the SET data, we formalised our conversations into a reflexive inquiry approach, guided by the first author’s research interest in Bakhtinian precepts. This involved about six meetings spanning approximately one year of semi-structured professional conversations via Zoom around our shared teaching experiences. We reflected on the aggregate responses of students from the SET scores from 2017 and 2018, and carefully read qualitative comments about student observations and perceptions of our course. We collectively read and heard each other’s documented experiences of our own teaching, our interactions with our respective groups of students, and with one another—the experience of working as a team as well as our reactions to the SET scores and qualitative feedback. As we dialogued and exchanged ideas, we developed written reflections, captured by our restoried accounts.

Our conversations reflect Bakhtin’s (1981) dialogism in the dynamic entwinement of our utterances as we explored ideas and made sense of our experiences. Unlike ‘reflection’, which is private and occurs after an event or moment, ‘reflexivity’ is “ongoing and relational” (Lyle, 2017, p. vii). Reflexive inquiry (RI) is synergistic with Bakhtinian perspectives. Through dialogue, we supported and expanded upon one another’s ideas as well as sometimes suggesting alternative interpretations and disputing positions (Bakhtin, 1981). At the end of each meeting, we collaboratively devised an individual writing exercise focused on issues that had emerged organically in conversation. While only fragments appear in this paper, this process was critical to our sense-making and ongoing interior dialogue.

Our autobiographical ‘snapshots’—brief reflexive narratives—reflect our interpersonal dialogue as well as our interior dialogue, capturing a different theme that emerged from conversations within and between ourselves. These themes were identified by their recurrence in our reflexive conversations and written reflections, and selected for inclusion in this paper by discussing and agreeing upon themes that that could illuminate different but connected aspects of our struggles. The snapshots are historically anchored in our shared and private experiences teaching into the educational technology course, but they also stretch into the present and future. As we grappled with discomfort, we also explored how this experience shaped and continues to shape our professional practice and sense of self, in relation to technology and more broadly.

Our continuous dialogue allowed us to highlight and chronicle critical events highlighting our respective encounters with discomfort that we realised were connected. Rather than resort to adopting inclusion and exclusion criteria, we chose to highlight the connectedness of our sense-making experiences of struggle and discomfort in enacting AL in an educational technology course. From these, our continued dialogues allowed us to surface chronotopes that we believe form an integral part of our continuing professional practice and sense of self. We then attempted to document these narratives forming part of our reflexive inquiry. In this manner our “writing provides an opportunity to turn from theming and finding commonalities or patterns, to listening to fragments that ravel together as entwined restoried experiences” (Charteris et al., 2017, p. 344).

Like Parr et al. (2020), developing and including these snapshots was, “driven less by a need to ‘choose a methodology’ … and more by our desire to create a richly dialogic research dynamic” (p. 245). Like autoethnography, reflexive inquiry can help the researcher to “use ‘self’ to learn about the other” (Ellis & Bochner, 2000, p. 741). For us, dialogue around our struggles teaching into a technology-rich ITE course helped us make sense of our own and one another’s discomfort as mechanisms of professional growth and change. We now proceed to describe these restoried sense-making experiences as illustrative snapshots.

Snapshots of struggle

In this section, we each share a brief autobiographical snapshot that captures the varied types of discomfort we experienced in relation to the educational technology course we designed and taught, and considers how professional conversations helped us make sense of that discomfort.

Discomfited by student feedback (Kate)

I remember being excited and terrified by the opportunity to redesign a course. We talked through the historical challenges the course had faced to identify how we should redesign the course to focus on the twenty-first century skills we were targeting. I felt confident that many aspects would be well-received by students. For example, flipping most content into shorter weekly learning videos seemed logical, reflecting contemporary learners’ desire to learn ‘anytime, anywhere’ (Shippee & Keengwe, 2014). So, I was taken aback when student feedback data revealed that almost a quarter disliked this approach, with less than 15% expressing positive views. Further, the overall course rating was disappointing; I had been optimistic it would be much higher as attendance had been strong, and students seemed to participate productively in the Sandpit-Synergy-Showcase tutorials, often producing digital artefacts that exceeded my expectations, which seemed to endorse peer-learning as an effective AL strategy.

Our professional conversations around the SET data were profoundly important to my sensemaking of my disappointment and puzzlement. Exploring our emotional responses—bewilderment, frustration, confusion—necessarily involved working to understand our students’ perspectives. Learning about ourselves helped us learn about the other: our students. These conversations increased my sensitivity to my students’ diverse views about and capacity in relation to technology, helping me refine and improve my pedagogy. Further, our professional conversations were a dialogic space through which I came to view SET data as an authoritative discourse that I had the agency to resist. As we talked through the discomfort aroused by these data, I was able to synthesise my intellectual understanding that active learning can be unsettling and confusing (Dall’Alba & Bengtsen, 2019) with my lived experience. As a result, I developed an internally persuasive discourse that allows me to “navigate and negotiate” SET data (Fecho & Clinton, 2016, p. 54). A ‘discomfort chronotope’ emerged, allowing me to engage dialogically and purposefully with SET data. This meant I became not only more open to new practices and possibilities, but also more able to normalise the feeling of discomfort and failure evoked by SET data, recognising it as part of my professional growth.

Grappling with emotional labour (Lauren)

Initially, many students seemed reluctant to engage with new technology, and equally dubious about tutors being ‘critical friends’. This meant we were supporting students academically, cognitively, and emotionally. While emotional labour is an acknowledged dimension of academic work (Constanti & Gibbs, 2004; Zhou et al., 2019) and the notion of ‘digital natives’ has long been regarded as a myth by education researchers (Smith et al., 2020), I was discomfited that our students—overwhelmingly young adults familiar with diverse technologies—needed so much coaxing to take risks, experiment with, and explore unfamiliar digital tools. Many students wanted to be shown how to use a specific tool rather than collaboratively exploring that tool in the Sandpit.

How, I wondered, can we cultivate the skills students need in a VUCA world if they are unwilling or unable to navigate the discomfort that necessarily accompanies volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity? Both in person and via email, students often expressed anxiety. Frequently, they were not seeking support with their learning and asking actionable questions but expressing an emotional state without a specific request. This meant I tended to students’ emotional needs just as, if not more often, than their academic needs. I was regularly reassuring and reminding them of the importance of self-direction, collaboration, problem-solving, and critical reflection both as learners and future teachers. This made me acutely aware that I needed to be an effective teacher both cognitively and affectively to help my PSTs become effective learners and teachers in a VUCA world where technology is ubiquitous and ever evolving. However, I also wonder whether this emotional labour blurred the boundaries of our responsibilities as teachers and learners.

Another tension revolved around active learning experiences—which can be unsettling and confusing (Dall’Alba & Bengsten, 2019)—and the impact on student evaluations of teaching. Does ‘assessing’ the course and teacher misconstrue learning as an experience that students should enjoy? As ‘edutainment’ (McNaught, 2020) rather than as a process that can be challenging and change-provoking? If so, to what extent does this stultify teachers’ creativity and risk-taking in favour of approaches more likely to yield satisfied ‘customers’ rather than curious, resilient, adaptable learners and future teachers?

Over time, by shifting the focus away from assessment outcomes and towards the process required to complete the assessment, I felt I more capably engaged my students—practically and conceptually—with learning as involving both challenges and triumphs. My hope is that this enabled my students to understand that learning is not always linear nor comfortable and often, not easily measured. And further, to accept that discomfort and struggle are not signs of failure, but mechanisms of growth and change (Edmiston, 2016).

Unsettled by active learning (Vicente)

In our first ALPP sharing session in which different teams from across the faculty shared findings from their action learning projects, I was unsettled to hear how positive other teams’ experiences were compared to ours. All the other teams described how they integrated technology into their courses in very interesting ways to support AL, but one remarkably common trait was that their student feedback scores improved dramatically. Objectively, as I compared the active learning approaches deployed by other teams to the approaches we used, there was a lot of similarity. However, our student feedback scores painted a vivid picture of polarisation. While a moderate percentage of our students seem to ‘love’ the course, another corresponding percentage apparently ‘hated’ it. For weeks, I racked my brain—why were students’ views of our transformed course so polarised? I wondered what it was about the changes we made that accounted for this unflattering indictment.

When I reflect on the conversations among the teaching team, particularly about issues and challenges, it was clear that we all experienced various kinds of distress as we navigated uncharted territory. Dialogue around this phenomenon with my co-authors has led me to this conclusion: A deliberate turn towards AL in higher education means that stakeholders will necessarily experience discomfort. As Dall’Alba and Bengsten (2019) suggest, the active learning approaches we adopted in the transformed course, coupled with unfamiliar technologies, caused our PSTs to feel unsettled, confused and perhaps even incompetent. Indeed, I felt similarly when I recognised that many PSTs were resistant to not only the greater agency required of them by AL, but also to the course focus on technology enhanced learning itself.

I struggled to understand this resistance until the Bakhtinian flavour of our professional conversations helped me reconceive the students’ discomfort and resistance as diverse perspectives with which we all needed to grapple as part of our ideological becoming. Both as teachers and learners, we were developing cognitive knowledge and skills as well as ways of “thinking, making and acting” (Dall’Alba & Barnacle, 2007, p. 682)—ideological positions—in relation to technology, teaching and learning, each other, and ourselves. I still sometimes question whether we were asking too much of both students and teaching staff, but I’m confident that through this learning journey, we emerged as more flexible, creative, and confident teachers and learners.

Discussion: Bakhtinian professional conversations to make sense of discomfort

We believe that our preliminary insights address one of the fundamental gaps in current research of active learning in technology-rich contexts. For example, Tharavil et al. (2018) focuses on student resistance, Finelli et al. (2018) identify strategies to overcome this resistance, and Hwang et al. (2018) propose specific approaches to incorporate smart use of technology to complement AL. However, little has been written about the challenges of AL through the lens of an emerging professional practice and the experiences of tertiary educators. It is worth mentioning that Bennet et al. (2017) have attempted to map university teachers’ engagements with technology, albeit with a focus primarily on the principle of design studies. Similarly, Philipsen, et al. (2019) in undertaking a systematic review articulated integrated strategies about Online Blended Learning for Teacher Professional Development (TPD), a topic that is arguably related to our inquiry but does not engage fully with the challenges and complexities for educators.

Our Head of School’s encouragement to take risks in redesigning the course seems prescient in light of Lin and Johnson’s (2021) recent assertion that despite the presence of educational technology for decades, relevant stakeholders "are not prepared to address the rapid and dramatic needs to change and shift” (p. 1). This paper is an account of our efforts to shift our practice to better prepare our students to become practising teachers who feel competent and capable to deploy technology with their own students, and we suggest three key learnings from our experience.

First, our formal and informal professional conversations were valuable dialogical tools that helped us reflect on practice. Kate’s snapshot illustrates how student feedback made visible the diverse perspectives of teaching with and about technology, and how professional conversations supported adjusted practices that better account for this diversity. This aligns with Edmiston (2016) who, in the context of teacher education, argues that there must be opportunities to dialogue with competing chronotopes for teachers’ classroom practice to evolve. This requires an understanding of difference—and the tension and struggle that accompanies it—as an opportunity rather than obstacle.

An example of this understanding of difference is the discomfort evoked in us by the SET data. Dialogic engagement with these data was supported through professional conversations that invoked chronotopic ‘chunks of history’ (Blommaert, 2010) and we suggest that ‘discomfort chronotopes’ emerged. For Kate, this manifested in the development of an internally persuasive discourse around SET data that allowed her to navigate, negotiate, and even resist the authority of these data. In Lauren’s case, the entwinement of emotional and academic labour became visible as PSTs and course staff wrestled with new ways of teaching and learning, generating discomfort chronotopes around the ways that AL pedagogies disrupt traditional teacher–student hierarchies. Similarly, for Vicente, ‘making room’ for discomfort in the various competing discourses he encountered in the contact zone of the course supported an increasingly nuanced view of technology rich AL approaches to teaching and learning.

As Mackenzie (2021) notes, our work as academics is “tied to our identities” (p. 3). As such, we can perceive negative student evaluations and student resistance to our innovations as not simply a professional failure but a personal failure. Our professional conversations created a safe collegial environment for dialogic—as opposed to solitary and isolated—exploration of student feedback. Our conversations reassured us “that failure is a normal dimension of being human” (Timmermans & Sutherland, 2020, p. 44). Further, the Bakhtinian flavour of our dialogic engagement helped us make sense of the cognitive disequilibrium we experienced when our innovations, which we had optimistically felt would be well received by students, were instead resisted. As we dialogued around the student experience, we began to understand students’ anxiety about unfamiliar technologies, and their desire for familiar (more traditionally passive) teaching and learning experiences. This understanding can help us to anticipate and be proactive about student resistance to AL. For example, incorporating and explicitly engaging students with scholarship around the challenges of active learning into courses like ours—as opposed to treating AL unproblematically—may help students critically reflect on their own feelings of discomfort and resistance.

Bakhtinian perspectives can also help us reconceptualise discomfort as the manifestation of Bakhtin’s ‘worthwhile struggle’ with competing discourses. While our physical bodies communicate, through discomfort, that something is wrong, perhaps the discomfort evoked as we engage in our own and our students’ ideological becoming tells us that something is right—a paradox indeed. As McNaught (2020) observes, encountering diverse pedagogical beliefs can be a “powerful opportunity for academic development” (p. 85). In ITE, dialogue with these diverse pedagogical beliefs and opportunities for development is vital, not only to educators but also to PSTs who are developing pedagogical beliefs and philosophies. However, the stressors on higher education—the system and its people—constrain such engagement (McNaught, 2020).

For example, Lauren reflected on the impact of commodification in education. She grappled with tensions arising from a course designed to cultivate difficult-to-quantify twenty-first century skills and dispositions on one hand, and easy-to-quantify student grades on the other. Mackenzie (2021) argues that using dialectical tensions—“contradictions driven by needs or struggles between competing systems; oppositions that negate one another” (p. 1)—can help us reframe our understanding of pedagogical failure and also communicate these real or perceived failures in more productive ways as we engage in “useful dialogue with students, colleagues, and leadership” (p. 6). For us, drawing on Bakhtinian precepts to anchor our professional conversations generated ‘useful dialogue’ that helped us appreciate aspects of student feedback that could enhance our future practice as well as unproductive feedback to which we needed to be resilient. And these tensions are not mutually exclusive—we can be both ‘sensitive’ and ‘thick skinned’, and course design can comprise both successful and failed dimensions (Mackenzie, 2021).

Finally, our professional conversations can support our professional ‘ideological becoming’ as we (i) learn from failure and refine our practice (Edminston, 2016) and (ii) reconceptualise discomfort as worthwhile. Our professional conversations have supported shared and private dialogue with difference, allowing us to interrogate both the authoritative discourses that ‘govern our thinking’ (Gomez et al., 2015) and our own and others’ internally persuasive discourses. For example, we suggest that student evaluation data are an example of authoritative discourse. While the reliability of student evaluations is contested, these data are nevertheless widely used to inform employment decisions around tenure and promotion (Mortelmans & Spooren, 2009; Spooren et al., 2013). Whether reliable or not, student evaluations are used to judge the quality of the courses we design and deliver. These data ‘govern our thinking’ (Gomez et al., 2015)—our view of our effectiveness and value as educators influences our pedagogical choices and shapes our professional sense of self. From a Bakhtinian perspective, student evaluations give us a sense of ourselves through the eyes of an other. This is a human, emotional experience common to every level of academia; we all feel rejection, elation, and everything in between (Probyn, 2020).

However, reconceiving failure as worthwhile discomfort and engaging with diverse perspectives around pedagogy and learning allows us to decide what will ultimately be internally persuasive for us. In this way, we can make purposeful pedagogical decisions, and communicate these in theoretically and philosophically defensible ways to our colleagues and students. This is particularly valuable in ITE, where we are supporting PSTs to learn about themselves as both teachers and learners (Jones, 2009). Appreciating that teaching and learning involves not only cognitive but ideological development can help PSTs and ITEs to understand struggle as a mechanism of growth and change that is critical to learning (Edmiston, 2016; Freedman & Ball, 2004).

Conclusion: Making room for discomfort

This paper has described our shared experience teaching into an educational technology course that deployed AL principles to cultivate twenty-first century skills in our preservice teachers. We have explored how our professional conversations, underpinned by Bakhtinian dialogism and the concepts of ‘ideological becoming’ and chronotope, helped us make sense of our discomfort and struggles, both throughout the course and later when interrogating the student evaluation data. Bakhtin’s precepts became enmeshed with our intra- and inter-personal dialogue, supporting our ‘ideological becoming’ as teacher educators. This is evident in, for example, the development of internally persuasive discourses that may not align with authoritative discourses around SET data and AL pedagogy, and the emergence of ‘discomfort chronotopes’ that reconceptualise discomfort as a worthwhile struggle.

We suggest that the capacity to conceive struggle, discomfort, and failure as unavoidable in a technology rich VUCA world is an inherent but under-theorised dimension of twenty-first century capacities. For example, Bell (2016), argues that a narrow focus on twenty-first century capacities as employability skills ignores issues of social justice. Dishon and Gilead (2021) similarly argue that the discourse around twenty-first century skills as essential for an unpredictable future marginalises the role of values in education. Future research could more closely interrogate and problematize 21st skills as comprising not just skills but sensibilities, including the value of appreciating discomfort and struggle as necessary and worthwhile in a VUCA world. This seems particularly valuable in the current historical moment of the COVID19 pandemic. Shifting learning online required teachers and learners to alter their cognitive and relational practices, a continuing widespread phenomenon that has abruptly “forced us to re-structure the delivery of education and the use of technology” (Reyes et al., 2021, p. 13). As such, there is also value in future research exploring how a Bakhtinian conception of struggle in ideological development could illuminate and problematize learning technology research, a field which is increasingly exploring more nuanced and holistic ways of understanding technology-enhanced teaching and learning.

Relatedly, we endorse Mackenzie’s (2021) call to make “time and space for dialogue about our teaching failures … [because this] can create the kind of connections and teachable moments sought after by both students and junior faculty alike” (p. 6). For example, given the well documented negative impact of student feedback on faculty members’ mental health (Lakeman et al., 2021), we suggest that tertiary educators could be actively supported and encouraged to connect with colleagues with whom they can dialogue safely and constructively around student feedback. This could not only support tertiary educators’ wellbeing but could contribute to a culture that supports and normalises failure-based learning. Further, openly discussing teaching failures, how these can arise from competing tensions, and strategies for managing the dual sense of professional and personal failure could provide valuable professional development as well as overcome the solitariness that so often characterises academic life and work (Timmermans & Sutherland, 2020). Of course, the twin constraints of funding and time poverty are challenges here.

This paper illustrates how entwining Bakhtinian precepts with dialogue around our shared and private teaching experience generated professional conversations that helped us ‘set a place at the table’ for struggle and discomfort instead of simply interpreting them as a sign of failure, as well as problematising the notion of ‘failure’ itself. Our experience and ongoing reflection on that experience illustrates that dialogic engagement with competing perspectives, authoritative discourses, and our own and others’ internally persuasive discourses supports sensemaking of the discomfort that arises from struggle, and helps us appreciate that we cannot be the teachers our students need us to be without it.

Change history

11 April 2023

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

References

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (2022). General Capabilities (Version 9). Retrieved from https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/f-10-curriculum-overview/general-capabilities

Bakhtin, M., & Medvedev, P. N. (1978). The formal method in literary scholarship: A critical introduction to sociological poetics (A. J. Wehrle, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. (C. Emerson, Ed.; M. Holquist, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

Bearden, S. M. (2016). Digital citizenship: A community-based approach. Corwin Press.

Blackledge, A., & Creese, A. (2017). Translanguaging in mobility. In The Routledge handbook of migration and language (pp. 31–46). Routledge.

Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalisation. Cambridge University Press.

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1.

Brewer, R., & Movahedazarhouligh, S. (2018). Successful stories and conflicts: A literature review on the effectiveness of flipped learning in higher education. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(4), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12250

Brown, R., & Renshaw, P. (2006). Positioning students as actors and authors: A chronotopic analysis of collaborative learning activities. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 13(3), 247–259.

Care, E., Scoular, C., & Bui, M. (2014). Australia in the context of the ATC21S project. Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp. 183–197). Springer, Netherlands.

Chai, C. S., & Kong, S. C. (2017). Professional learning for 21st century education. Journal of Computers in Education, 4(1), 1–4.

Charteris, J., Jones, M., Nye, A., & Reyes, V. (2017). A heterotopology of the academy: Mapping assemblages as possibilised heterotopias. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(4), 340–353.

Constanti, P., & Gibbs, P. (2004). Higher education teachers and emotional labour. International Journal of Educational Management, 18, 243–249.

Coorey, J. (2016). Active learning methods and technology: Strategies for design education. The International Journal of Art & Design Education, 35(3), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12112

Dall’Alba, G. (2009). Learning to be professionals (Vol. 4). Springer.

Dall’Alba, G., & Barnacle, R. (2007). An ontological turn for higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 32(6), 679–691.

Dall’Alba, G., & Bengtsen, S. (2019). Re-imagining active learning: Delving into darkness. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 51(14), 1477–1489.

Davidson, C. N. (2017). The new education: How to revolutionize the university to prepare students for a world in flux (1st ed.). Basic Books.

Davies, A., Fidler, D. & Gorbis, M. (2011). Future work skills 2020. Institute for the Future for University of Phoenix Research Institute. Retrieved from http://www.iftf.org/futureworkskills/

Dishon, G., & Gilead, T. (2021). Adaptability and its discontents: 21st-century skills and the preparation for an unpredictable future. British Journal of Educational Studies, 69(4), 393–413.

Edmiston, B. (2016). Promoting teachers’ ideological becoming: Using dramatic inquiry in teacher education. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 65(1), 332–347.

Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 733–768). Sage.

Fecho, B., & Clifton, J. (2016). Dialoguing across cultures, identities, and learning: Crosscurrents and complexities in literacy classrooms. Taylor & Francis.

Finelli, C. J., Nguyen, K., DeMonbrun, M., Borrego, M., Prince, M., Husman, J., & Waters, C. K. (2018). Reducing student resistance to active learning: Strategies for instructors. Journal of College Science Teaching, 47(5), 80–91.

Freedman, S. W., & Ball, A. F. (2004). Ideological becoming: Bakhtinian concepts to guide the study of language, literacy, and learning. In A. F. Ball & S. W. Freedman (Eds.), Bakhtinian perspectives on language, literacy, and learning (pp. 3–33). Cambridge University Press.

Germaine, R., Richards, J., Koeller, M., & Schubert-Irastorza, C. (2016). Purposeful use of 21st century skills in higher education. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching, 9(1), 19–29.

Gomez, M. L., Lachuk, A. J., & Powell, S. N. (2015). The interplay between service learning and the ideological becoming of aspiring educators who are “marked” as different. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 162–172.

Gordon, J., Halász, G., Krawczyk, M., Leney, T., Michel, A., Pepper, D., Putkiewicz, E., & Wiśniewski, J. (2009). Key competences in Europe: Opening doors for lifelong learners across the school curriculum and teacher education. CASE Network Reports No. 87 (Warsaw, CASE - Center for Social and Economic Research).

Holquist, M. (1990). Dialogism. Taylor & Francis.

Hwang, G. J., Chang, S. C., Chen, P. Y., & Chen, X. Y. (2018). Effects of integrating an active learning-promoting mechanism into location-based real-world learning environments on students’ learning performances and behaviors. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(2), 451–474.

Jones, M. (2009). Transformational learners: Transformational teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 34(2), 15.

Kivunja, C. (2014). Innovative pedagogies in higher education to become effective teachers of 21st century skills: Unpacking the learning and innovations skills domain of the new learning paradigm. International Journal of Higher Education, 3(4), 37–48.

Lakeman, R., Coutts, R., Hutchinson, M., Lee, M., Massey, D., Nasrawi, D., & Fielden, J. (2021). Appearance, insults, allegations, blame and threats: An analysis of anonymous non-constructive student evaluation of teaching in Australia. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 2021, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.2012643

Leblanc, P. J. (2018). Higher education in a VUCA world. Change: the Magazine of Higher Learning, 50(3–4), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2018.1507370

Lin, L., & Johnson, T. (2021). Shifting to digital: Informing the rapid development, deployment, and future of teaching and learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(1), 1–5.

Lyle, E. (2017). Of books, barns, and boardrooms: Exploring praxis through reflexive inquiry. Sense Publishers.

Mackenzie, L. (2021). The role of dialectical tensions in making sense of failures in teaching and learning. Transformative Dialogues: Teaching and Learning Journal, 14(1), 1–9. Retrieved from https://td.journals.psu.edu/td/article/view/1477/973

Matsushita, K. (2018). An invitation to deep active learning. In K. Matsushita (Ed.), Deep active learning: Toward greater depth in university education (pp. 15–33). Springer Nature.

Matusov, E. (2007). Applying Bakhtin scholarship on discourse in education: A critical review essay. Educational Theory, 57(2), 215–237.

McLay, K., & Reyes, V. C., Jr. (2019a). Problematising technology and teaching reforms: Australian and Singapore perspectives. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 21(4), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-10-2018-0045

McLay, K., & Reyes, V. C., Jr. (2019b). Identity and digital equity: Reflections on a university educational technology course. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(6), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5552

McNaught, C. (2020). A narrative across 28 years in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(1), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1701476

Misseyanni, A., Lytras, M. D., Papadopoulou, P., & Marouli, C. (2018). Introduction. In A. Misseyanni, M. D. Lytras, P. Papadopoulou, & C. Marouli (Eds.), Active learning strategies in higher education (pp. 1–13). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Mizokami, S. (2018). Deep active learning from the perspective of active learning theory. In K. Matsushita (Ed.), Deep active learning: Toward greater depth in university education (pp. 79–91). Springer Nature.

Mortelmans, D., & Spooren, P. (2009). A revalidation of the SET37 questionnaire for student evaluations of teaching. Educational Studies, 35(5), 547–552.

Nissim, Y., Weissblueth, E., Scott-Webber, L., & Amar, S. (2016). The effect of a stimulating learning environment on pre-service teachers’ motivation and 21st century skills. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(3), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v5n3p29

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2005). Are students ready for a technology-rich world? What PISA studies tell us. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/programmeforinternationalstudentassessmentpisa/35995145.pdf

Parr, G., Bulfin, S., Diamond, F., Wood, N., & Owen, C. (2020). The becoming of English teacher educators in Australia: A cross-generational reflexive inquiry. Oxford Review of Education, 46(2), 238–256.

Penuel, W. R., & Wertsch, J. V. (1995). Vygotsky and identity formation: A sociocultural approach. Educational Psychologist, 30(2), 83–92.

Philipsen, B., Tondeur, J., Pareja Roblin, N., Vanslambrouck, S., & Zhu, C. (2019). Improving teacher professional development for online and blended learning: A systematic meta-aggregative review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(5), 1145–1174.

Probyn, E. (2020). Emotions. In H. F. Wilson & J. Darling (Eds.), Research ethics for human geography: A handbook for students (pp. 67–72). Sage Publications Ltd.

Renshaw, P. D. (2004). Dialogic learning teaching and instruction. In J. van der Linden & P. Renshaw (Eds.), Dialogic learning: Shifting perspectives to learning, instruction, and teaching (pp. 1–15). Springer, Netherlands.

Reyes, V., McLay, K., Thomasse, L., Olave-Encina, K., Arafeh, K., Tareque, M., Seneviratne, L., & Tran, T. (2021). Enacting smart pedagogy in higher education contexts: Sensemaking through collaborative biography. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 26, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-021-09495-5

Shippee, M., & Keengwe, J. (2014). mLearning: Anytime, anywhere learning transcending the boundaries of the educational box. Education and Information Technologies, 19(1), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-012-9211-2

Smagorinsky, P., Cook, L. S., & Johnson, T. S. (2003). The twisting path of concept development in learning to teach. Teachers College Record, 105(8), 1399–1436.

Smith, E. E., Kahlke, R., & Judd, T. (2020). Not just digital natives: Integrating technologies in professional education contexts. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(3), 1–14.

Spooren, P., Brockx, B., & Mortelmans, D. (2013). On the validity of student evaluation of teaching: The state of the art. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 598–642.

Tharayil, S., Borrego, M., Prince, M., Nguyen, K. A., Shekhar, P., Finelli, C. J., & Waters, C. (2018). Strategies to mitigate student resistance to active learning. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 1–16.

The University of Queensland. (2017–2018). Active Learning Pathways Project (ALPP). Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation. Retrieved June 10, 2020 from https://itali.uq.edu.au/about/projects/tig/alpp

Timmermans, J., & Sutherland, K. (2020). Wise academic development: Learning from the “failure” experiences of retired academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1704291

Valtonen, T., Sointu, E., Kukkonen, J., Kontkanen, S., Lambert, M. C., & Mäkitalo-Siegl, K. (2017). TPACK updated to measure pre-service teachers’ twenty-first century skills. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(3), 15–31.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1934/1987). Thinking and speech. In R. Rieber & A. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky: Volume I. Problems of general psychology (pp. 39–285). Plenum. (Original work published 1934.)

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). In M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

World Economic Forum. (2020). The Future of Jobs Report. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2020.pdf

Wortham, S. (2006). Learning identity: The joint emergence of social identification and academic learning. Cambridge University Press.

Zhou, F., Wang, N., & Wu, Y. J. (2019). Does university playfulness climate matter? A testing of the mediation model of emotional labour. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 56(2), 239–250.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge that this research has been supported by The University of Queensland through the project, Strengthening the gateways: Building pathways to success through active learning/Active Learning Pathways Project (2017–2018) (Grant No. 2017001085).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The authors would like to acknowledge that this research has been supported by The University of Queensland through the project, Strengthening the gateways: Building pathways to success through active learning/Active Learning Pathways Project (2017–2018) (Grant No. 2017001085).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No financial or non-financial conflicts to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study adheres to the Guidelines of the ethical review process of The University of Queensland and the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Ethics ID number: 2017001085.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McLay, K.F., Thomasse, L. & Reyes, V.C. Embracing discomfort in active learning and technology-rich higher education settings: sensemaking through reflexive inquiry. Education Tech Research Dev 71, 1161–1177 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10192-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10192-6