Abstract

Due to the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China, a large number of Chinese students resorted to online learning resources. The increasingly widespread online education enables the investigation of public opinion about this large-scale untraditional mode of learning during this critical period. Sina Weibo Microblogs (the Chinese equivalent of Twitter) related to online education were collected in three distinctive phases: from July 01, 2019 to January 09, 2020 (pre-pandemic); from January 10, 2020 to April 30, 2020 (amid-pandemic); and from May 01, 2020 to Nov 30, 2020 (post-pandemic), respectively. The aim was to obtain broad insight into how online learning was viewed by the public in the Chinese educational landscape. The public opinion during these three periods were analysed and compared. The findings facilitated a better understanding of what the Chinese public perceived about this online learning mode in becoming the dominant channel for teaching and learning during critical periods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In January 2020, the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) broke out in mainland China with the key characteristics of a pandemic virus, and rapidly spread to many cities in the country within several weeks. Soon, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared it as a public health emergency of international concern. In the event of prolonged public health threats, such as COVID-19, online learning courses, platforms and resources have been shown to be timely and effective in serving as alternative outlets for learning (Cumbers, 2020; Schwartz & Bayles, 2012). In recognition of this situation, the Chinese central government disseminated online higher education and K-12 education-specific pandemic influenza guidance and recommended the use of distance courses for all grade levels. As a consequence, almost all schools and institutions had to rely on electronic forms of learning to reach students and continue their learning. However, this transition to online learning involved a lot more than flipping a switch. Proponents of online learning have posited that moving face-to-face classes online could become an important component of the academic continuity planning (Allen & Seaman, 2010). Whereas opponents of this pointed out increasing difficulties with creating individually tailored differentiated instruction for each student in online environments (Gillett-Swan, 2017), and students may need additional motivation, scaffolding, organization, and self-discipline to be successful in their online learning endeavors (Jacob & Radhai, 2016).

Public opinion has obtained considerable scholarly attention. While online learning boomed during the pandemic, either on a voluntary or an involuntary basis, public attention has been drawn to this transformation in teaching and learning during this critical period. The purpose of this study was thus to track the changes in perceiving, understanding and experiencing online learning before, during and after COVID-19, using social media data. While efforts have been made in analysing such large-scale data on various topics during the pandemic, such as online healthcare forums (Jelodar et al., 2020), events related to COVID-19 (Wahbeh et al., 2020), social prejudice (Croucher et al., 2020) and etc., relatively less attention has been paid to online education during this outbreak using large open datasets with a few exceptions such as student attitudes towards it (Unger & Meiran, 2020) and user satisfaction (Chen et al., 2020). With the limited number of studies on examining public responses to online education by adopting a longitudinal perspective, we attempted to gather data from social media on this topic and compare the public’s opinions before, during and after the pandemic. Specifically, how positive (or negative) did the Chinese public feel about online learning, and what was of their utmost concern about online learning? Given the concerns about the presence and impact of a “gender gap” on Internet access and usage (Colley & Maltby, 2008), one significant area of research over the last decade in examining social media perception and usage has focused on gender differences. As Ong & Lai (2006) argued, providing more detailed information about users’ views across gender is increasingly important for learning technology stakeholders. Thus, it is important to examine whether their views on online learning varied across periods of time and across gender. The findings would make up for the limited literature on the adoption of online education in case of emergencies, so as to improve the education level from more perspectives.

Literature review

Online education in China

Online education is not new to the educational community in this century, with rapid developments in technology (McBrien et al., 2009). Accessibility, affordability, flexibility, learning pedagogy, and life-long learning are some buzzwords related to online education (Dhawan, 2020). Compared to the days whereby online learning was taken as an optional mode for enriching or optimizing traditional teaching and learning, it is now emerging as a necessity, especially in emergency events. Many universities and schools around the globe have fully digitalized their operations with an understanding of the dire need of the pandemic. During this tough time, the concern is not about whether online education can ensure quality education; rather, it is more about how schools and institutions will be able to make effective use of online learning in such a massive manner (Carey, 2020).

Online education in China has increased exponentially during the outbreak. With the world’s largest student population of the 176 million K-12 students, online education tools have been a natural progression for China, with impressive fiber, broadband and Internet coverage across the country and over 800 million Chinese citizens being Internet users (Kologrivaya & Shleifer, 2020). During the outbreak, online classes have been the main solution for schools and higher institutions to adapt to the changing situation, with an overnight shift of normal classrooms into e-classrooms. While some foresee that the unplanned and rapid move to online learning will result in poor learning experiences that are unconducive to sustained growth due to little professional training, insufficient bandwidth, and insufficient preparation, Others are expecting to witness a new hybrid model of education with significant benefits. As Tao, the Vice President of Tencent Cloud and Vice President of Tencent Education, posited, “the integration of information technology in education will be further accelerated and that online education will eventually become an integral component of school education.” (Li & Lalani, 2020).

Public opinions on new forms of technologies in education

It has been widely recognized that understanding the processes through which the public makes sense of technologies and develop responses to them is critical for the design and coordination of mechanisms for public engagement and participation (Macnaghtena et al., 2019). Researchers have empirically confirmed the importance of examining public opinion to new forms of technologies in education and identified relevant factors and issues (Zhou, 2020). For example, Giannakoulopoulos et al. (2019) tracked the public opinion about online education by analyzing tweets on e-learning and found the prevalence of one-way promotional material over bidirectional discussions among users, which suggested a necessity for quality control of educational information on social media. More recently, Fu et al. (2020) analyzed GDELT and Twitter data to examine public opinion about online education during COVID-19 using python.

The growing theoretical literature concerning public opinion towards emerging technologies revealed three main approaches: individuals’ general level of knowledge and attentiveness, trust in institutional actors and regulatory bodies, and individuals’ values/ethical considerations (Weldon & Laycock, 2009). This echoed Kardooni et al.’s (2018) framework which comprised four variables: cost, knowledge, trust and intention to adopt a certain type of technology. The “Deficit Model” discussed individuals’ knowledge and understanding of new technologies with the main assumption that the public would embrace new technologies if it were more knowledgeable about the benefits and limited risks of the technology (Sturgis & Allum, 2004). Under this assumption, a concerted effort to raise public awareness and knowledge will be necessary to increase support for the adoption of technology (Bodmer, 1985).

The trust in institutional actors and stakeholders is concerned with the trust of institutional actors and stakeholders for support of new technologies (Priest et al., 2003). In other words, individuals tend to look to trusted official sources to help them make decisions, particularly when they perceive a personal lack of knowledge in that area. This has been confirmed in previous studies (Barnett et al., 2007; Durant & Legge, 2005). To this extent, the public’s trust in technology stakeholders, government rules and regulatory bodies carries more weight than knowledge about science per se (Weldon & Laycock, 2009). The third approach of individuals’ ethical concerns and core values include their religious and moral inclinations. These orientations towards technology are embedded in spiritual beliefs, worldviews, and value positions (Cook & Fairweather, 2005). People’s affective orientations towards specific technologies have been found to be critical heuristics that help guide individual judgments (Weldon & Laycock, 2009), and greatly increase the explanation of variance in individual perceptions about technologies (Sjoberg, 2000).

The above theories provided guidelines when we sought to examine public opinions about technology. However, in the case of COVID-19, the use of technology in education is not an option but the only outlet that sustains learning opportunities. Public agencies, political entities, and research institutions may enable and constrain learning during a disease outbreak crisis (Muller-Seitz & Macpherson, 2014). Relative to users’ knowledge and religious/moral beliefs about new technology, the enforcement of online education by government and stakeholders of education in China carries the most weight, which could greatly affect the formation of opinions about online forms of learning. As Blumberg (2008) posited, the political power still dominates the country (China), despite the growth, openness, and diversification of religious beliefs. As such, the rudimentary form of a general model of public opinion towards online education in China is well reflected in the second approach as reviewed above. The extent to which the public trusts in government policies and technology stakeholders becomes more critical in determining how well or badly the public can accept, engage, and experience alternative learning modes.

Public perceptions about online education during crisis events

Recent three-factor theory and its extended factor theory identified a range of factors that influenced public opinion on education network. Each factor received a specific weight through the analytic hierarchy process, among which crisis events was assigned the second highest weight right after noumenon of public opinion (Li et al., 2021). Previous research on Ebola outbreaks has identified that knowledge and attitudes of students on disease transmission can help inform best practices for public health (Holakouie-Naeieni et al., 2015). During the SARS and H1N1 outbreaks of 2002 and 2008, Hong Kong implemented complete online schooling (Barbour et al., 2011), yet quite limited research was conducted regarding how students were impacted when schools had to close unexpectedly, indefinitely, and switched to online learning communities during a catastrophic and an urgent event (Unger & Meiran, 2020).

During COVID-19, several studies were conducted with large-scale social media datasets with the purpose of revealing how the public perceived and experienced online education. For example, Persada et al. (2020) explored public perceptions of online learning applications in Indonesia using Twitter data. Results showed that Indonesian students had a positive attitude towards online learning, and even had a significant willingness to recommend an online learning application when they found it useful to learn subjects taught at school. However, their study was conducted before the outbreak (from March to June 2019). The most relevant study was conducted by Chen et al. (2020) who collected online user experience data of seven major online education platforms in China within two periods: Nov 16, 2019 to Dec 16, 2019 and Feb 17, 2020 to March 17, 2020. They found that before the outbreak, users were concerned about the access speed, reliability, and timeliness of video information transmission of the platform, and the user experience of the Zoom Cloud platform was the best among all candidate platforms. After the outbreak, users mainly focused on course management, communication and interaction, learning and technical support services of the platform, and the user experience of the platform was the most important. Nonetheless, their data were restricted by the chosen learning platforms and did not address the semantic dimension of public opinions as expressed in the social networking platform. This present study aimed to fill in these research gaps.

Gender differences in social media on online education

Researching gender effects on the adoption of online learning has become more wildly implemented in recent years (Hilao & Wichadee, 2017; Park et al., 2019). Classic research on gender differences in decision-making processes has indicated significant differences in schematic processing by males and females (Bem & Allen, 1974). In view of this difference, it is not surprising that males and females respond differently to the emergence of new types of technology. In a recent meta-analysis by Cai et al. (2017), males held more favorable attitudes toward technology use than females, and there was only minimal reduction in the gender attitudinal gap in general. But when the general attitude was broken down to different dimensions, smaller gender differences in attitudes towards technology use were only observed in affect (about personal feelings and emotions such as comfort, anxiety, or personal liking associated with technology use) and self-efficacy (about one's ability in utilizing technology), but not in belief (concerning the usefulness of technology and its social impact).

With regards to online education in particular, Park et al. (2019) verified the moderating effect of gender difference between perceived usefulness of technology and intention to use it for learning— the effect of perceived usefulness on intention to use was greater for males, suggesting that men tend to be highly task-oriented when it comes to the adoption of technology. Other researchers also found the effect of gender on the determinants of adopting a new technology. For example, Moghavvemia et al. (2017) found that the effect of social influence was more salient in females when forming the intention to use a new technology, since females tended to be more sensitive to the opinion of others. In addition, females were more concerned about the existence of support and facilitating conditions to use e-learning. We believe that the findings from this line of research would help us better understand the adoption mechanism and gender differences in employing technology for online learning. As such, an investigation of gender differences in the public’s attitudes and thoughts toward online education would also inform policy makers, school leaders and online learning designers of how to encourage and improve learning processes against potential gender obstacles.

Present study

Microblogs have been used extensively to collect public opinions on different topics, such as responses to public emergencies (Fang et al., 2020), food safety (Zheng et al., 2020), MOOCs (Zhou, 2020), global climate change (Dahal et al., 2019), and so forth. By providing updates about themselves or sharing information on such platforms (Naaman et al., 2010), microblogs can convey information reflecting the emotional states of their authors. Microblogs facilitate the public to express their opinions regarding different issues (Dong et al., 2017), The large-scale data generated from these platforms allow researchers to examine whether the results generated by smaller-scale studies stand up to scrutiny, enable investigations of samples drawn at random from large populations, or investigate questions that can only be answered by larger datasets (Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2018). These public sources reveal important technical, social, institutional, pedagogical, and other related challenges surrounding online education and can inform future research about important topics of the highest societal and public importance (Kovanović et al., 2015).

According to the 2020 Weibo User Development Report, Weibo had 523 million active users. Despite social media censorship in China, the relatively liberal nature of this social networking platform allows users to openly share opinions on the advantages and disadvantages of any educational ideology. With the aim to solicit the public opinions about the adoption of online learning in China during COVID-19, we chose Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, for data collection. As such, Weibo is considered as encompassing microscopic instantiations of public sentiment and opinions.

This study distinguishes itself from all existing studies in online education in at least three aspects. First, the analysis of large-scale datasets enables a comprehensive view of the topic under investigation. It is timely as this information is needed for different stakeholders to assess, monitor, and even predict the acceptance, utilization and efficiency of online education. Second, during this critical historical period, the three distinctive periods allow us to present a chronological view of public opinions on online education. Through this view, a roadmap can be identified for future research and development based on public demand, especially in response to emergency occasions. Third, simply moving a learning community online does not mean that it automatically becomes less aggressive or free of the gender-related problems that plague traditional classrooms (Anderson, 2006). Potential gender differences in online education-related microblogs were examined in this study based on the sentiment values during different periods. Scholars have found that female online students had to cope with insufficient interaction with teachers, problems or frustration with the technology (Müller, 2008), and asynchronous text-based online discussion may well suit females who are shy or reticent or who prefer more time to digest the content (Gunn et al., 2003).

As such, the current study was guided by the following research questions:

-

(1)

What was the overall online education-related microblog activity before, during and after the pandemic, respectively?

-

(2)

What was the pattern of the sentiment values of public opinion on online education before, during and after the pandemic, respectively?

-

(3)

Were there any gender differences in overall online education-related microblog activity and the pattern of sentiment values before, during and after the pandemic, respectively?

-

(4)

What were the main topics as shown in online education-related microblogs before, during and after the pandemic, respectively?

Method

Data collection

Microblog data were extracted with a self-developed algorithm using the following search terms: 在线教育 (online education), 远程教育 (distance education), 远程学习 (long-distance learning), 互联网教育 (internet education), 电子学习 (e-learning), 手机教学 (mobile teaching), 网课 (online course/class), 多媒体学习 (multimedia learning), 在线课程 (online course), 在线学习社区 (online learning community), 网络教育 (web education), 网络教学 (web-based teaching), 微课教育 Microlecture), 函授教育 (correspondence education), 联机学习 (online learning), 在线学习 (online learning), 网络学习 (e-learning), 网上学习 (web-based learning), 慕课 (MOOC), 网易公开课 (NetEase Online Open Courses), 学堂在线 (XuetangX), 沪江.

(Hujiang), 酷学习 (Kuxuexi), 可汗学院 (Khan Academy), 好大学在线 (CNMOOC), 中国大学(Chinese University), 新浪公开课 (Sina open course), 茱莉亚公开课 (Juilliard open course), CCTV中国公开课 (CCTV openCLA), 万门大学 (One-Man University), 百度传课 (Baidu Chuanke), 腾讯课堂 (Tencent Classroom), 优酷教育 (YouKu education), YY教育 (YY Education), 人民网公开课 (People’s Online Course), 优课联盟 (University Open Online Course), 高校一体化教学平台 (university integrated teaching platform), EduCoder在线实践教学平台 (EduCoder online practical teaching platform), 高校邦 (Gaoxiaobang), and 优学院 (Ulearning).

As reported in the White Paper by The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China (2020), the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic was first revealed in July 2019 at Wuhan, Hubei Province. Since then, clusters of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology gradually emerged and confirmed cases were subsequently reported in other Chinese regions. A few months later, as the virus carriers traveled around the country, a nationwide spread signaled the peak of COVID-19 from 10th January 2020. Although a lockdown was imposed on Wuhan with travel restrictions, the number of daily confirmed cases rapidly reached 15,152 on 12th February. Efforts were made to consolidate gains in virus control, resulting in reported cases generally under control. At the beginning of May 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping concluded that China achieved a major strategic success in COVID-19 control efforts, and stressed that nationwide virus prevention was conducted on an ongoing basis. Schools were reopened, and people resumed work as control measures are still ongoing until 30th November, wherein a “new normal” was achieved. Therefore, public responses to online education were collected from Weibo according to these three milestones: from 1st July, 2019 to 9th January, 2020 (pre-pandemic phase); from 10th January, 2020 to 30th April, 2020 (amid-pandemic phase); and from 1st May, 2020 to 30th Nov, 2020 (post-pandemic phase), respectively.

Within each specified timeframe, the relevant data were first collected and then processed using the MS Excel application. A second-level cleansing of the dataset was conducted by filtering out microblogs by zombie accounts (automated accounts with the purpose of inflating follower counts). All user identity details were removed to ensure anonymity and unbiased analysis. The final dataset included 212,335 microblogs by 87,100 users from 1st July, 2019 to 9th January, 2020, 1,048,575 microblogs by 538,021 users from 10th January, 2020 to 30th April, 2020, and 561,004 microblogs by 287,963 users from 1st May, 2020 to 30th Nov, 2020.

We retrieved gender information from user profiles on Weibo that described a series of personalized features of a specific user. This presented useful attributes including gender, age, occupation, location, and etc. (Yu & Yao, 2017). Although self-reported information might suffer from unintentional or intentional errors, this gender information retrieval method has been used widely in past research on social media (e.g., Li et al., 2014a, b ; Yang et al., 2013). Other user information was not be considered due to its unavailability (such as occupation) or incompleteness (such as age).

Data analysis strategies

As the process of determining the attitude or polarity of opinions (Liu, 2010), sentiment analysis has been applied to textual forms of opinions such as Facebook posts and comments (Hajhmida & Oueslati, 2021), public perceptions of chemistry (Guerris et al., 2020), (Santos et al., 2018), and the impact of research articles (Hassan et al., 2020), to name a few, to reveal behavioral and affective trends, and explain people's sentiments, attitudes, beliefs, and emotions (Persada et al., 2020). Sentiment analysis can be applied at three levels of detail: document, sentence, and entity/aspect (Dragoni et al., 2019). In this study, we adopted BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) model with sentence pair input for an aspect-based sentiment analysis. BERT is a pre-trained language representation model proposed based on deep learning techniques by a Google AI team in 2018 (Devlin et al., 2019). Different from other language representation models, BERT can generate deep bidirectional representations from the unlabeled input text. This model can achieve outstanding results for text recognition and classification (Sun et al., 2019), and encoding information from a huge amount of unlabeled data and fine-tuned on small supervised datasets specifically designed for certain tasks (Pota et al., 2021).

The sentiment analysis started with a pre-processing phase to remove spammers or those blogs intended for commercials from the dataset. The BERT model was then used in its pre-trained version on the text, because the pre-trained models avoid the time-consuming and resource intensive model training directly on microblogs from scratch, and allow to focus only on their fine-tuning (Pota et al., 2021). By dividing the microblog data into positive, negative, and neutral categories, each microblog was tagged with a numerical sentiment value of − 1, 0, or + 1 to indicate negative, neutral, or positive polarity, respectively.

In addition to sentiment analysis, content analysis was conducted to identify popular topics in online education-related microblogs. Content analysis has been well applied in the analysis of microblogs and online discussions on various topics, such as public transit (Casas & Delmelle, 2017), financial market (Li et al., 2018), and higher education (Pizarro Milian & Rizk, 2019). To provide deeper insight into how the community perceives online education in the Chinese educational landscape, especially over the period of COVID-19, microblog content was examined more closely to obtain a dynamic picture of how people reacted, and what elaborative ideas were contained in the microblogs and whether online education really remedied the urgent educational needs during the pandemic.

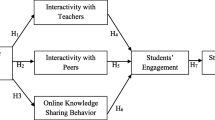

For content analysis, natural language processing (NLP) was first used for clustering messages related to a topic to identify the topics of concern (Zolnoori et al., 2019). Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm (Bicalho et al., 2017) was adopted for this purpose as it has often been used to automatically identify the latent semantic topics in unstructured textual data, such as tweets or microblogs (Chen et al., 2018). The “Gensim” package (Řehůřek & Sojka, 2010) in Python was used to implement the LDA model. We then used the Hierarchical Dirichlet Process (HDP, Teh et al. 2006) to infer the number of topics from the data (Bertalan & Ruiz, 2019; Wong et al., 2019). To extract the discussed topics from the dataset, Gensim first cleaned the dataset by tokenising each sentence into a list of words and removing the punctuations and unnecessary characters. With the help of Gensim’s phrases model, we could create bigrams and trigram models, preparing for the next step of building the dictionary and corpus. LDA model was then built with different topics. Each topic was a combination of keywords and each keyword contributed a certain weightage to the topic. A flowchart is provided in Fig. 1 which describes the data analysis procedure.

Results

General description

Figure 2 shows the total number of microblogs about online education before, during and after COVID-19, respectively. In general, the number of microblogs increased dramatically during the pandemic, with the peak reaching 430,566 in March 2020. After the pandemic, the number of microblogs about online education dropped again to a similar level to that before the pandemic. The lowest record (around 9000) of microblogs appeared in Nov 2020. Another look at the data showed that the dramatic increase of the number of microblogs about online education largely came from female users. Before the pandemic, females and males seemed to be equally “indifferent” to online education, but this pattern changed greatly during the pandemic. As shown in Fig. 3, the number of microblogs from females boomed during the pandemic whereas the number of microblogs male users only varied to some extent. After the pandemic, the gender gap was diminished, as indicated by the number of microblogs which returned to the previous pattern.

Sentiment analysis

The sentiment data were reorganized according to the three main periods of time to identify the public opinion trend over COVID-19. Figure 4 revealed the percentages of public opinions based on sentiment value. Overall, the public expressed neutral perceptions of online education (on average 79.03%) with an extremely small portion of negative perceptions (on average 4.67%) before the pandemic. During the pandemic, however, the percentage of Weibo users holding neutral views about online education dropped to 33.04% while those with negative views increased to 51.63%. The percentage of positive views stayed the same. After the pandemic, the pattern somehow returned to the previous state, with neutral views taking the majority. Figure 5 provides a gender-based comparison of the change in positive, neutral, and negative public opinions. Over the outbreak, females’ negative opinions about online education increased from 5.53 to 19.17%, and did not drop very much after the pandemic (16.21%). Their positive views showed a steadily decreasing trend over the pandemic. In comparison, males seemed to hold a positive view on online education, regardless the phases. Although the percentage of negative opinions increased over the outbreak, the portion of females almost doubled that of males in being negative about online education.

Content analysis

There is no universal rule for determining the number of topics existing in a dataset. To find the optimal number of topic, we followed most studies (Cha & Cho, 2012; Kobayashi, 2014; Vu et al., 2019) by using perplexity, which is based on the probability of unseen test set, normalized by the number of words to evaluate the goodness of LDA model (Neishabouri & Desmarais, 2020). To calculate the perplexity, we first trained and evaluated an LDA model on the dataset. This routine was then repeated for models with different numbers of topics, so that it became clear which amount led to the lowest perplexity (Jacobi et al., 2016), as a lower perplexity indicates a better prediction (Blei et al., 2003). The value of perplexity for the number of topics was represented as “weight” in Fig. 6. We observed that when the optimal number of topics was set to be 2 in the pre-pandemic dataset, the perplexity ceased to be continuously decreasing when it reached 0.024. Similarly, the optimal number of topics was set to be 4 in the amid-pandemic dataset because the weight ceased to decrease when it reached 0.028, and the optimal number of topics was set to be 7 in the post-pandemic dataset when the weight stopped decreasing when it reached 0.020. As the number of topics increased, the granularity of the topic became finer which did not contribute much more to our understanding of the content of each topic. We examined the top 15 tokens from each topic to represent the theme. Table 1 lists the word-level topics as identified by LDA.

We integrated semantically related information into one theme. This led to a more abstract categorization of the content compared to the machine-detected categories. Before the pandemic, the first topic was mainly concerned with the purposes and functions of online education, in a positive tone. Participants also mentioned the instrumental value of learning online, such as for graduate study. The second topic was more related to personal experience while using online education, both in a positive (e.g., success) and negative (e.g., pressure) way. During the pandemic, the number of topics increased to 4. Given the outbreak, the terms that emerged reflected the special concern with schools, teachers, students and curricula. For example, Topic 1 in this period explicitly included such terms as “prevention and control”, “pandemic”, and “China”. This reflected the close relationship between online education and external environment at the macro level. Topic 2 was more related to the users of online education, including teachers and students, and their education and future. Topic 3 was more personally related, such as personal mood and growth. The last topic during this period was more school-related, including terms of “homework”, “course”, “internet surfing” and etc.

After the pandemic, despite the decreasing number of microblogs, the topics that emerged from the Weibo were of an even bigger variety. Among the seven topics, Topic 1 and 4 were more political than other topics as shown in the key term of “resisting”, “education bureau” and “resistance”, as a response to the actions made by the government of suspending schools during the outbreak. Topic 2 was about resuming face-to-face classes after the pandemic. Topic 3 seemed to be more concerned with one’s life at a more general level with the use of online education, such as personal growth, life taste, and so on. Topic 5 tapped on the multiple consequences of adopting online education, such as learning English and popularizing science. Topic 6 was more related to how students made fuller or better use of online education, by mentioning instructors and studying, with a particular focus on personal experiences such as working hard. Topic 7 presented technology-related posts about online education, such as “tablet”, and “zoom in/out”. Positive emotional terms mainly appeared in Topic 3, as shown by the keywords of “passion, active”, where a bit of negative emotions were expressed in Topic 5 such as “anxiety”.

Discussion

This study examined Chinese public responses to online education based on social media data. To address the first research question (Research Question 1) about the overall trend over COVID-19, the results suggested that public interest in distance education was on a quite stable trend both before and after the pandemic, as reflected in the even number of microblogs. When we entered the phase of the pandemic, the number of microblogs increased almost three times within Jan 2020. The peak was seen in March 2020, when the whole country closed schools and institutions switched to online learning completely. This shows that emergency situations influence public concerns about education to a great extent (Li et al., 2021), when the public is engaged in a form of education, they were eager to express their thoughts and opinions. This pattern was particularly salient in females (Research Question 3). Further examination of the limited info on users’ age showed that over 80% of the users who were engaged in Weibo activities were post-90 s and post-00 s females, who were most likely in their student phase of life. Yan et al. (2021) have reported that females were more vulnerable to developing mental or psychological problems in response to life stressors or potentially traumatic events. Anxious individuals tended to use social media more often to actively seek a path to adapt to the current pandemic situation (Cauberghe et al., 2021).

With regards to the second question (Research Question 2) on sentiment values of public opinion on distance education in China, the results revealed a steadily low, positive view with respect to adopting online forms of teaching and learning, regardless of whether it was COVID-19 (between 10 and 20%). The most dramatic change in the percentage of sentimental value was found in those holding negative perspectives towards online education. During the pandemic, it was more than 10 times of the percentage before the outbreak. This result aligned with a recent study on Chinese user satisfaction with selected online education platforms during the pandemic (Chen et al., 2020), but stood in contrast with past studies that examined the public view of online learning such as MOOCs. In a series of time-series studies (Zhou, 2020; Costello et al., 2016), negative opinions of MOOCs seemed to remain stable with only a small portion. Research has shown that remote learning can be as good or better than in-person learning for the students who chose it (Fitter et al., 2020). It appeared that the public became more negative when they were “forced” to engage in and be adapted to online education on an involuntary basis during the pandemic. This was well explained by the self-determination theory that one’s autonomy of making decisions in learning (e.g., choosing learning mode) determined learners’ attitude to a great extent (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Indeed, learning theories have articulated the downside of requesting learners to adopt a given mode of learning, which jeopardizes their motivation as well as attitude. People feel more autonomous when they are enabled to choose between options (Katz & Assor, 2007). This sense of autonomy promotes successful learning experiences and satisfaction (Ghanizadeh, 2016).

Further to explore this issue by looking at potential gender differences in microblog activities based on the sentiment patterns (Research Question 3), the results revealed that females’ negative opinions constituted the main reason for the above observation during the pandemic, with the percentage of females nearly doubling the number of males. This was in line with Cai et al. (2017) meta-analysis and Shapiro et al. (2017) sentiment analysis on gender and attitudes toward technology use that males held more favourable attitudes toward technology use than females. It appeared that female Weibo users became bigger in number and more negative while engaged in online education during the outbreak, and this trend even continued into the post-pandemic phase. More recently, Prowse et al. (2021) also observed that female students were more likely than male students to find the transition to online learning difficult during this critical period and that the COVID-19 had negatively impacted their learning.

Subsequent content analyses sought to address the potential model to be developed based on the content of microblogs (Research Question 4). The keywords extracted from the Weibo dataset by LDA analysis generated different user profiles, which can be classified into a threefold typology based on the views of how distance education functioned over COVID-19. Before the pandemic, the positive tone in both topics confirmed the power of online education that can help with one leveling up the life standard (as seen in taking postgraduate and English language exams) in the hope of bringing better changes to one’s life. We thus profiled them as “affirmative” users. During the pandemic, more attention was paid to school, curricula, teachers and students. Apparently, online education has been integrated into a daily practice during this special phase, unlike being an option for furthering one’s study and growth before the pandemic. When online education became a dominant mode of teaching and learning, the public was more concerned with its curriculum design and learning effectiveness. We thus profiled them as “achievement-based” users. After the pandemic, the public attended to different aspects of online education. Some people cared more about the social political consequences of adopting online education and suspending/re-opening schools. Some people reflected about how this decision affected our life in general. Others were more concerned with technological aspects of learning online, while the rest were still viewing it as part of school education. We thus profiled them as “critical” users.

Caution is needed when interpreting our results. First, microblogs are not the only outlet through which the public can voice its opinions. Many netizens also opted for the more private WeChat’s Moment for such purposes (Li et al., 2014a, b). Thus, although a considerably large number of microblogs were analyzed, it could be argued that the sample size was still insufficient to generalize the observed trends. Personal websites, chat boards, discussion forums, and other types of social media can also provide invaluable information for a more solid conclusion. Further, one may argue that the topics obtained through LDA might be not optimal and that different hyperparameters could have generated more coherent topics. Unfortunately, the literature on this issue gives very little advice on how such optimization can be achieved (Péladeau & Davoodi, 2018). While Mimno et al. (2011) proposed to optimize LDA through internal or external coherence measures, optimizing topic modeling this way tended to favor topics lacking independence. Last, the analysis of key terms and word frequency alone may not be able to capture the full picture. As Tsou (2015) posited, studying such public data from social media needs to include the complexities of human dynamics and spatiotemporal analysis. In future studies, other data sources could be considered such as survey (O’Connor et al., 2010). To analyze and visualize social media data more effectively, we could combine, integrate, and cross-reference multiple data sources together and explore their dynamic spatiotemporal patterns in visual graphs (such as a visual cluster analysis, Zhao et al., 2020 or word shift graphs, Cody et al., 2015). By doing so, we can generate big ideas, big impacts, and big changes toward the future development of research in this area.

Conclusions and implications

Online education has traditionally been viewed as an alternative pathway, one that is particularly well suited to adult learners seeking higher education opportunities. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has required educators and students across all levels of education to adapt quickly to virtual courses. The pandemic has forced the world to engage in the ubiquitous use of virtual learning (Lockee, 2021). Despite the above limitations, the user-generated large-scale dataset in this study provides a holistic view and can be effectively used to understand and possibly improve learners’ experiences online by capturing their most important concerns, compared to purely instrument-driven survey-based studies (e.g., Bakhmat et al., 2021) which restrict the expression of public opinion to a certain reference frame and small-scale studies involving only selected online learning platforms (e.g., Chen, Peng, et al., 2020).

Academic implications

The current study makes several unique contributions to the existing online education literature. First, this study focuses on the context of China which was largely neglected in previous studies of public views to online education (Giannakoulopoulos et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2020). The present study provides insights and offers diverse perspectives of online education research so as to enable the field to take a more active role in societal conversations of interest. The massiveness and magnitude of the datasets yield tremendous data and the analysis of these data (Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2018) prepares a useful and timely tool to assess the orientation of Chinese public opinion toward new forms of teaching and learning.

Another innovation of this research is the attention to the pandemic period, a historical phase in human history. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt in analysing public opinions about online education in China during this period. By attending to the emotional orientations of online posts over the outbreak, researchers are better informed of the developmental trend of online interaction over such an abrupt transition to online learning. Subsequent gender analyses highlighted the need to attend to females versus males’ attitudes and thoughts about online education. It was exciting to see more females in China were active in voicing their perceptions and thoughts, although they were expressed in a more negative manner than their male counterparts, which provides us with a new territory to revisit this issue.

Last, the user profiles generated by our LDA analyses pointed to the need to attend to the variation of public opinion about online education both temporally and laterally, as well as the direction when we attempt to establish such a model. As past models of public opinion tended to focus on one temporal dimension or multiple dimensions within the same timeframe, we proposed the possibility that the public opinion model could vary substantially across periods of time and the context within each period makes a case for re-examining the content and trend of public opinion about the same issue/phenomenon.

Practical implications

The findings have great implications for different stakeholders in online education as well. First, and fundamentally, the results from the current study confirm that the Chinese users as a whole became more critical about the idea of online education especially after the pandemic. The experience of a forced and hurried review of instructional approaches provided a rare opportunity to reconsider/reformulate strategies that best facilitate learning within the affordances and constraints of the online context (Lockee, 2021). In particular, the expectations of online learners to be highly self-disciplined and self-regulated are challenging to be met (Gillett-Swan, 2017). “Sleepy” and “anxious” also appeared in the keywords in our content analysis. Thus, a greater variance in teaching and learning online activities is needed to maximize the value of “staring at screen” during lengthy online sessions.

While acknowledging the value and benefit of online education, the negative views shown in our datasets alerts us of staying critical about it. As online education is promised to be a pervasive force that can meet our emergent needs during unexpected events, questions about how to reach the financially disadvantaged population should be central to the field as we do not want to sacrifice the effort to develop a more just and fair educational system. One topic that emerged from our content analysis suggested that technology is a big concern to enable this form of education. This is an even bigger challenge than the concern with how to improve online teaching and learning pedagogy.

References

Allen, E., & Seaman, J. (2010). Learning on demand: Online education in the United States 2009. Sloan Consortium.

Anderson, B. (2006). Writing power into online discussion. Computers and Composition, 23(1), 108–124.

Bakhmat, L., Babakina, O., & Belmaz, Y. (2021). Assessing online education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of lecturers in Ukraine. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1840, 12–50.

Barbour, M., Brown, R., Waters, L. H., Hoey, R., Hunt, J., Kennedy, K., Ounsworth, C., Powell, A., & Trim, T. (2011). Online and blended learning: A survey of policy and practice from K-12 schools around the world. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from https://files.eric.edu.gov/fulltext/ED537334.pdf

Barnett, J., Cooper, H., & Senior, V. (2007). Belief in public efficacy, trust, and attitudes toward modern genetic science. Risk Analysis, 27(4), 921–933.

Bem, D. J., & Allen, A. (1974). On predicting some of the people some of the time: The search for cross-situational consistencies in behavior. Psychological Review, 81(6), 506–520.

Bertalan, V. G., & Ruiz, E. E. S. (2019). Using topic modeling to find main discussion topics in Brazilian political websites. In: Proceedings of the 25th Brazillian Symposium on Multimedia and the Web (pp. 245–248). New York: ACM.

Bicalho, P., Pita, M., Pedrosa, G., Lacerda, A., & Pappa, G. L. (2017). A general framework to expand short text for topic modeling. Information Sciences, 393, 66–81.

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022.

Blumberg, F. (2008). When east meets west: Media research and practice in US and China. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Bodmer, W. (1985). The public understanding of science. Royal Society.

Cai, Z., Fan, X., & Du, J. (2017). Gender and attitudes toward technology use: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 105, 1–13.

Carey, K. (2020). Everybody ready for the big migration to online college? Actually, no. The New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from www.nytimes.com/2020/03/13/upshot/coronavirus-online-college-classes-unprepared.html

Casas, I., & Delmelle, E. C. (2017). Tweeting about public transit—gleaning public perceptions from a social media microblog. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 5(4), 634–642.

Cauberghe, V., Van Wesenbeeck, I., De Jans, S., Hudders, L., & Ponnet, K. (2021). How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(4), 250–257.

Cha, Y., & Cho, J. (2012). Social-network analysis using topic models. In: Proceedings of the 35th international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval (pp. 565–574). ACM.

Chen, J., Chen, M., Qu, J., Chen, H., & Ding, J. (2018). Smart and connected health projects: Characteristics and research challenges. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Smart Health (pp. 154–164). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Chen, L., Liu, Y., Chang, Y., Wang, X., & Luo, X. (2020). Public opinion analysis of novel coronavirus from online data. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 1(2), 120–127.

Chen, T., Peng, L., Jing, B., Wu, C., Yang, J., & Cong, G. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on user experience with online education platforms in China. Sustainability, 12(18), 7329.

Cody, E. M., Reagan, A. J., Mitchell, L., Dodds, P. S., & Danforth, C. M. (2015). Climate change sentiment on Twitter: An unsolicited public opinion poll. PloS one, 10(8), e0136092.

Colley, A., & Maltby, J. (2008). Impact of the Internet on our lives: Male and female personal perspectives. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(5), 2005–2013.

Cook, A., & Fairweather, J. (2005). New Zealanders and biotechnology: Attitudes, perceptions and affective reactions. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://researcharchive.lincoln.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10182/730/aeru_rr_277.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Costello, E., Nair, B., Brown, M., Zhang, J., Nic Giolla Mhichíl, M., Donlon, E., & Lynn, T. (2016). Social media #MOOC mentions: Lessons for MOOC mentions from analysis of Twitter data. In: Proceedings of ASCILITE 2016 Adelaide (pp. 157–162). Adelaide, Australia: University of South Australia.

Croucher, S. M., Nguyen, T., & Rahmani, D. (2020). Prejudice toward Asian Americans in the COVID-19 pandemic: The effects of social media use in the United States. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 39.

Cumbers, J. (2020). As coronavirus spreads, house-bound Chinese students are causing an online ed-tech boom. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from www.forbes.com/sites/johncumbers/2020/02/12/as-coronavirus-spreads-house-bound-chinese-students-are-causing-an-online-ed-tech-boom/#6e6a0bda1418

Dahal, B., Kumar, S. A., & Li, Z. (2019). Topic modeling and sentiment analysis of global climate change tweets. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 9(1), 1–20.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Devlin, J., Chang, K., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Paper presented in Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. USA: Minneapolis.

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5–22.

Dong, Y., Ding, Z., Chiclana, F., & Herrera-Viedma, E. (2017). Dynamics of public opinions in an online and offline social network (pp. 1–11). IEEE Transactions on Big Data.

Dragoni, M., Federici, M., & Rexha, A. (2019). An unsupervised aspect extraction strategy for monitoring real-time reviews stream. Information Processing & Management, 56(3), 1103–1118.

Durant, R. F., & Legge, J. S., Jr. (2005). Public opinion, risk perceptions, and genetically modified food regulatory policy: Reassessing the calculus of dissent among European citizens. European Union Politics, 6(2), 181–200.

Fang, W., Gao, B., & Li, N. (2020). Analysis of the influence of opinion leaders on public emergencies through microblogging. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 8(5), 154–158.

Fitter, N. T., Raghunath, N., Cha, E., Sanchez, C. A., Takayama, L., & Matarić, M. J. (2020). Are we there yet? Comparing remote learning technologies in the university classroom. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 5(2), 2706–2713.

Fu, Z., Yan, M., Meng, C., Wang, W., Hu, X., Li, Y., Wang J, He Z, & Wang, Z. (2020). Opinion mining about online education basing on GDELT and Twitter data. In Proceeding of 2020 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology (WI-IAT) (pp. 741–745). IEEE.

Ghanizadeh, A. (2016). The interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education. Higher Education, 74, 101–114.

Giannakoulopoulos, A., Kouretsis, A., & Limniati, L. (2019). Tracking the public’s opinion of online education: A quantitative analysis of tweets on e-learning. International Journal of Learning Technology, 14(4), 271–287.

Gillett-Swan, J. (2017). The challenges of online learning: Supporting and engaging the isolated learner. Journal of Learning Design, 10(1), 20–30.

Guerris, M., Cuadros, J., González-Sabaté, L., & Serrano, V. (2020). Describing the public perception of chemistry on twitter. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 21(3), 989–999.

Gunn, C., McSporran, M., Macleod, H., & French, S. (2003). Dominant or different: Gender issues in computer supported learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 14–30.

Hajhmida, M. B., & Oueslati, O. (2021). Predicting mobile application breakout using sentiment analysis of Facebook posts. Journal of Information Science, 47(4), 502–516.

Hassan, S. U., Aljohani, N. R., Idrees, N., Sarwar, R., Nawaz, R., Martínez-Cámara, E., Ventura, S., & Herrera, F. (2020). Predicting literature’s early impact with sentiment analysis in Twitter. Knowledge-Based Systems, 192, 105383.

Hilao, M. P., & Wichadee, S. (2017). Gender differences in mobile phone usage for language learning, attitude, and performance. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 68–79.

Holakouie-Naeini, K., Ahmadvand, A., Raza, O., Assan, A., Elduma, A. H., Jammeh, A., Kamali, A. S. M. A., Kareem, A. A., Muhammad, F. M., Sa-Bahat, H., Abdullahi, K. O., Saeed, R. A., & Saeed, S. N. (2015). Assessing the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of students regarding Ebola virus disease outbreak. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 44(12), 1670–1676.

Jacob, S., & Radhai, S. (2016). Trends in ICT e-learning: Challenges and expectations. International Journal of Innovative Research & Development, 5(2), 196–201.

Jacobi, C., Van Atteveldt, W., & Welbers, K. (2016). Quantitative analysis of large amounts of journalistic texts using topic modelling. Digital Journalism, 4(1), 89–106.

Jelodar, H., Wang, Y., Orji, R., & Huang, S. (2020). Deep sentiment classification and topic discovery on novel coronavirus or covid-19 online discussions: Nlp using lstm recurrent neural network approach. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 24(10), 2733–2742.

Kardooni, R., Yusoff, S. B., Kari, F. B., & Moeenizadeh, L. (2018). Public opinion on renewable energy technologies and climate change in Peninsular Malaysia. Renewable Energy, 116, 659–668.

Katz, I., & Assor, A. (2007). When choice motivates and when it does not. Educational Psychology Review, 19, 429–442.

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, G. (2018). Public internet data mining methods in instructional design, educational technology, and online learning research. TechTrends, 62(5), 492–500.

Kobayashi, H. (2014). Perplexity on reduced corpora. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the ACL ,1, 797–806. ACL.

Kologrivaya, E., & Shleifer, E. (2020). Quarantined: China’s-online education in the pandemic. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/quarantined-chinas-online-education-in-the-pandemic/

Kovanović, V., Joksimović, S., Gašević, D., Siemens, G., & Hatala, M. (2015). What public media reveals about MOOCs: A systematic analysis of news reports. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 510–527.

Li, L., Sun, M., & Liu, Z. (2014). Discriminating gender on Chinese microblog: A study of online behaviour, writing style and preferred vocabulary. In Proceedings of 2014 10th International Conference on Natural Computation (pp. 812–817). New York: IEEE.

Li, P., Chen, G., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Chinese research perspectives on society (Volume 3). Brill.

Li, C., & Lalani, F. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed education forever: This is how. Retrieved September 22, 2021, from www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/

Li, L. X., Huo, Y., & Lin, J. C. W. (2021). Cross-dimension mining model of public opinion data in online education based on fuzzy association rules. Mobile Networks and Applications. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11036-021-01769-7

Li, T., van Dalen, J., & van Rees, P. J. (2018). More than just noise? Examining the information content of stock microblogs on financial markets. Journal of Information Technology, 33(1), 50–69.

Liu, B. (2010). Sentiment analysis and subjectivity. In N. Indurkhya & F. J. Damerau (Eds.), Handbook of natural language processing (pp. 627–666). CRC Press.

Lockee, B. B. (2021). Online education in the post-COVID era. Nature Electronics, 4(1), 5–6.

Macnaghten, P., Davies, S. R., & Kearnes, M. (2019). Understanding public responses to emerging technologies: A narrative approach. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5), 504–518.

McBrien, J. L., Jones, P. T., & Cheng, R. (2009). Virtual spaces: Employing a synchronous online classroom to facilitate student engagement in online learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(3), 1–17.

Mimno, D., Wallach, H. M., Talley, E., Leenders, M., McCallum, A. (2011). Optimizing semantic coherence in topic models. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 262–272).

Moghavvemi, S., Sharabati, M., Paramanathan, T., & Rahin, N. M. (2017). The impact of perceived enjoyment, perceived reciprocal benefits and knowledge power on students’ knowledge sharing through Facebook. The International Journal of Management Education, 15(1), 1–12.

Müller, T. (2008). Persistence of women in online degree-completion programs. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 9(2), 1–18.

Müller-Seitz, G., & Macpherson, A. (2014). Learning during crisis as a ‘war for meaning’: The case of the German Escherichia coli outbreak in 2011. Management Learning, 45(5), 593–608.

Naaman, M., Boase, J., & Lai, C. H. (2010). Is it really about me?: Message content in social awareness streams. In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work (pp. 189–192). New York, USA: ACM.

Neishabouri, A., & Desmarais, M. C. (2020). Reliability of perplexity to find number of latent topics. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Flairs Conference. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

O'Connor, B., Balasubramanyan, R., Routledge, B. R., & Smith, N. A. (2010). From tweets to polls: Linking text sentiment to public opinion time series. In Proceedings of 4th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (pp.122–129). Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

Ong, C. S., & Lai, J. Y. (2006). Gender differences in perceptions and relationships among dominants of e-learning acceptance. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(5), 816–829.

Oueslati, O., Cambria, E., HajHmida, M. B., & Ounelli, H. (2020). A review of sentiment analysis research in Arabic language. Future Generation Computer Systems, 112, 408–430.

Park, C., Kim, D. G., Cho, S., & Han, H. J. (2019). Adoption of multimedia technology for learning and gender difference. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 288–296.

Péladeau, N., & Davoodi, E. (2018). Comparison of latent Dirichlet modeling and factor analysis for topic extraction: A lesson of history. In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Persada, S., Oktavianto, A., Miraja, B., Nadlifatin, R., Belgiawan, P., & Redi, A. P. (2020). Public perceptions of online learning in developing countries: A study using the ELK stack for sentiment analysis on Twitter. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 15(9), 94–109.

Pizarro Milian, R., & Rizk, J. (2019). Marketing Christian higher education in Canada: A ‘nested’fields perspective. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 29(2), 284–302.

Pota, M., Ventura, M., Catelli, R., & Esposito, M. (2021). An effective BERT-based pipeline for Twitter sentiment analysis: A case study in Italian. Sensors, 21(1), 133–154.

Priest, S. H., Bonfadelli, H., & Rusanen, M. (2003). The “Trust Gap” hypothesis: Predicting support for biotechnology across national cultures as a function of trust in actors. Risk Analysis, 23(4), 751–766.

Prowse, R., Sherratt, F., Abizaid, A., Gabrys, R. L., Hellemans, K. G., Patterson, Z. R., & McQuaid, R. J. (2021). Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining gender differences in stress and mental health among university students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 439.

Řehůřek, R., & Sojka, P. (2010). Software framework for topic modelling with large corpora. In Proceedings of the LREC 2010 workshop on new challenges for NLP frameworks (pp. 45–50). Valletta, Malta: University of Malta.

Santos, C. L., Rita, P., & Guerreiro, J. (2018). Improving international attractiveness of higher education institutions based on text mining and sentiment analysis. International Journal of Educational Management, 32(3), 431–447.

Schwartz, R. D., & Bayles, B. R. (2012). US university response to H1N1: A study of access to online preparedness and response information. American Journal of Infection Control, 40(2), 170–174.

Shapiro, H. B., Lee, C. H., Roth, N. E. W., Li, K., Çetinkaya-Rundel, M., & Canelas, D. A. (2017). Understanding the massive open online course (MOOC) student experience: An examination of attitudes, motivations, and barriers. Computers & Education, 110, 35–50.

Sjoberg, L. (2000). Factors in risk perception. Risk Analysis, 20(1), 1–11.

Sturgis, P., & Allum, N. (2004). Science in society: Re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Understanding of Science, 13(1), 55–74.

Sun, C., Qiu, X., Xu, Y., & Huang, X. (2019). How to fine-tune BERT for text classification? China national conference on Chinese computational linguistics (pp. 194–206). Springer.

Teh, Y. W., Jordan, M. I., Beal, M. J., & Blei, D. M. (2006). Hierarchical Dirichlet processes. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 101(476), 1566–1581.

The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 China in action [抗击新冠肺炎疫情的中国行动]. Retrieved September 24, 2021, from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-06/07/content_5517737.htm

Tsou, M. H. (2015). Research challenges and opportunities in mapping social media and big data. Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 42(sup1), 70–74.

Unger, S., & Meiran, W. R. (2020). Student attitudes towards online education during the COVID-19 viral outbreak of 2020: Distance learning in a time of social distance. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science (IJTES), 4(4), 256–266.

Vu, H. Q., Li, G., & Law, R. (2019). Discovering implicit activity preferences in travel itineraries by topic modeling. Tourism Management, 75, 435–446.

Wahbeh, A., Nasralah, T., Al-Ramahi, M., & El-Gayar, O. (2020). Mining physicians’ opinions on social media to obtain insights into COVID-19: Mixed methods analysis. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e19276.

Weldon, S., & Laycock, D. (2009). Public opinion and biotechnological innovation. Policy and Society, 28, 315–325.

Wong, A. W., Wong, K., & Hindle, A. (2019). Tracing forum posts to MOOC content using topic analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.07307

Yan, S., Xu, R., Stratton, T.D., Kavcic, V., Luo, D., Hou, F., Bi, F., Jiao, R., Song, K. & Jiang, Y. (2021). Sex differences and psychological stress: Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in China. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–8.

Yang, J., Counts, S., Morris, M. R., & Hoff, A. (2013). Microblog credibility perceptions: Comparing the USA and China. In Proceedings of the 2013 conference on Computer supported cooperative work (pp. 575–586). New York: IEEE.

Yu, Y., & Yao, T. (2017). Gender classification of Chinese Weibo users. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on E-Commerce, E-Business and E-Government (pp. 5–8). Turku, Finland.

Zhou, M. (2020). Public opinion on MOOCs: Sentiment and content analyses of Chinese microblogging data. Behaviour & Information Technolog. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2020.1812721

Zhao, Y., Cheng, S., Yu, X., & Xu, H. (2020). Chinese public’s attention to the COVID-19 epidemic on social media: Observational descriptive study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(5), e18825.

Zheng, C., Song, Y., & Ma, Y. (2020). Public opinion prediction model of food safety events network based on BP neural network. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Article 012078). Bristol: IOP Publishing.

Zolnoori, M., Balls-Berry, J. E., Brockman, T. A., Patten, C. A., Huang, M., & Yao, L. (2019). A systematic framework for analyzing patient-generated narrative data: Protocol for a content analysis. JMIR Research Protocols, 8(8), e13914.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by grants to Mingming Zhou from University of Macau (Multi-Year Research Grant number MYRG2019-00001-FED).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, M., Mou, H. Tracking public opinion about online education over COVID-19 in China. Education Tech Research Dev 70, 1083–1104 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10080-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10080-5