Abstract

Understanding theory is essential to instructional design (ID) research and practice; however, novice designers struggle to make sense of instructional design theory due to its abstract and complex nature, the inconsistent use of theoretical terms and concepts within literature, and the dissociation of theory from practice. While these challenges are generally understood, little is known about the sensemaking process of learners as they encounter these challenges in pursuit of deeper theoretical understanding. Using a collaborative autoethnographic approach, six ID learners investigated their sensemaking experience within an advanced ID theory course. Autoethnography, a form of qualitative research, focuses on self-reflection “to gain an understanding of society through the unique sense of self” (Chang et al., 2013, p. 18). Collaborative autoethnography, a type of autoethnography, explores anecdotal and personal experiences “collectively and cooperatively within a team of researchers” (p. 21). Using individual and collective reflexive and analytic activities, this inquiry illuminates the numerous sensemaking approaches ID learners commonly used to move beyond their initial, basic theoretical understanding, including deconstructing theory, distinguishing terminology, integrating concepts with previous knowledge, and maintaining an openness to multiple perspectives. Additionally, ID learners experienced significant struggles in this process but viewed these struggles as significant and motivating elements of their sensemaking process. Finally, this study offers implications for learners, instructors, and course designers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Instructional design (ID) theory is fundamental to design practice by promoting effective learning (Reigeluth, 1999), informing instructional choices (Smith & Boling, 2009), supporting sensemaking (Yanchar et al., 2010), and establishing a common knowledge base (Reigeluth & Carr-Chellman, 2009). Despite its value, novice instructional designers experience difficulty understanding and applying ID theory due to inconsistent and vague language used within the field (Bichelmeyer et al., 2006; Gibbons & Rogers, 2009; Reigeluth & Carr-Chellman, 2009), the complex and abstract nature of theory (Reigeluth, 1997; Yanchar et al., 2010), and the dissociation of theory from practice during training (Bichelmeyer et al., 2006). While researchers describe difficulties in developing theoretical knowledge (Belcher & Hirvela, 2010; Burri, 2017; Casanave & Li, 2015), very little empirical research specifically explores the theoretical sensemaking process of instructional design learners.

Literature review

The importance of theory for learners

Understanding instructional design (ID) theory is critical for learners and instructional designers. In some cases, “it is helpful to contrast it [ID theory] with what it is not”; therefore, ID theory is not a learning or curriculum theory (i.e., content of instruction or what should be learned) and is not an instructional design process (i.e., a guide, plan, or preparation procedure for instruction; Reigeluth, 1999, p. 12). Rather, ID theory “offers guidance on how to better help people learn and develop” and is described as design-oriented, prescriptive, and probabilistic (Reigeluth, 1999, p. 5). While experts in the field disagree about the definition and role of ID theory (see Delphi study in Reigeluth & Carr-Chellman, 2009), some have suggested that Elaboration Theory, ARCS Model of Motivation, Gibbons’s Layers of Design (or Design Layers), and Merrill’s First Principles could be considered as ID theories. Traditionally, ID theory has served as the primary means of advancing research and knowledge within ID (Reigeluth & Carr-Chellman, 2009; Yanchar et al., 2010), a conceptual tool to improve practice (Christensen, 2008; Yanchar et al., 2010), education (Reigeluth, 1999), and a support for understanding different perspectives and informing potential design solutions (Reigeluth, 1997). Furthermore, theory is a vital part of decision making within ID practice (Johnson, 1998; Winn, 1997), enabling practitioners to envision new possibilities, problem solve and design, and debate different perspectives (Wilson, 1997). Supported by theory, practitioners craft design interventions aligned within a unified framework, communicate instructional design activity, and adapt existing models to new situations (Tamez, 2016).

In graduate programs, theoretical understanding is essential for the learners’ emerging identity and expertise as researchers and practitioners. Success in graduate programs requires learners to become well-versed in theory (Silber, 1982) and research (Merrill, 2006). Identifying, modifying, and developing theory are critical steps in students’ scholarly pursuits (Merrill, 2006). While research illuminates the importance of theoretical understanding (Bichelmeyer et al., 2006; Merrill, 2006; Reigeluth & Carr-Chellman, 2009; Smith & Boling, 2009), less is known about how learners develop theoretical understanding.

Why learners struggle with ID theory

Several factors contribute to learners’ difficulty with theory. Learners are diverse, with a variety of skills and experiences, which may affect how they respond to the presentation of theory (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). If learners have limited experience with theory, theoretical definitions become more challenging to understand and apply (Scandura, 1996). Specifically in ID programs, theoretical understanding is inhibited when ID theory is represented in models that are described as linear and isolated processes, omitting the myriad of conditions involved with designing instruction (Jonassen et al., 1997; Reigeluth, 1997; Smith & Boling, 2009; Winn, 1997). This simplistic perspective of ID may lead novice instructional designers to develop overly procedural views of ID where theory is considered static rather than conditional and dynamic. Additionally, ambiguous and inconsistent theoretical terminology use within the field of ID may lead to confusion, misguided perceptions, and misinterpreted meanings, especially for novices (Bostwick et al., 2014; Reigeluth & Carr-Chellman, 2009).

Adding further complication, experienced designers often struggle to express and share with novices how instructional theories influence their designs (Gibbons & Rogers, 2009). ID theories may lack clear guidance regarding how they may directly benefit a design, potentially leading instructional designers to question the practical value of theory (Yanchar et al., 2010). Instructional designers may also struggle with the prescriptive nature of ID theory, viewing it as too rigid and limiting the designer’s decision-making ability (Yanchar et al., 2010).

Facilitating learners’ theoretical sensemaking

To alleviate discomfort associated with exploring theory, learners often seek direct answers. Grimmett (2016) described this request as “Please just tell us” (p. 44), an appeal often made to instructors by learners when faced with complex topics to avoid accompanying feelings of fear, uncertainty, and vulnerability. Monologic responses, however, reduce the opportunity for dialogue in which instructors and students co-construct meaning (Grimmett, 2016). In the interest of productive theoretical discourse, learners should consider new ideas, question their understanding, and be receptive to others’ views and alternate perspectives (Reigeluth & Carr-Chellman, 2009).

Theoretical sensemaking may be facilitated more effectively through pedagogical strategies allowing for learners’ personal exploration and investigation. Commonly aligned with constructivist principles, these strategies enable learners to interpret, reorganize, and create their own knowledge. Informal activities may also benefit learners’ theoretical sensemaking processes. For instance, self-reflection and concept mapping may help learners capture and track their personal understanding (Burri, 2017; Casanave & Li, 2015), and discussing theory with others may help learners develop a more in-depth understanding (Zhang & Soergel, 2014). Instructors can help learners develop a deeper knowledge about ID theory through the inclusion of conceptual and empirical studies from different disciplines, as exploration of other fields helps learners accumulate diverse approaches needed to build sound theoretical perspectives (Casanave & Li, 2015). When learners have the opportunity to participate in active, collaborative knowledge construction, and when instructors and learners share responsibility, transformative learning can occur (Wrenn & Wrenn, 2009).

Purpose

As doctoral level learners and instructional design novices, we investigated how we made sense of theory through self-reflection and critical examination of our course assignments, personal writings, and focus group discussions. Investigating learners’ theoretical knowledge and understanding can inform future ID curricula, research, and practice (Hardré et al., 2006; Yanchar et al., 2010). Specifically, we considered the following overarching research question:

-

How do instructional design learners make sense of theory in the field of instructional design?

Methods

Research design

We selected a qualitative research approach as our aim was to interpret and attribute meaning to our personal experiences (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Collaborative autoethnography (CAE), specifically, is applicable when investigating complex phenomena (Chang et al., 2013). As an emerging method undefined by one specific approach or style (Chang et al., 2013), CAE has been defined as “a qualitative research method in which researchers work in community to collect their autobiographical materials and to analyze and interpret their data collectively to gain a meaningful understanding of sociocultural phenomena” (pp. 23–24). Collaborative efforts (e.g., focus group meetings, discussions) provide opportunities for considering individual voices through examination, questioning, and probing, while individual meaning-making offers space for valuable reflection (Chang et al., 2013).

Participants and setting

This study took place at a large Midwestern public university in a 16-week Advanced Instructional Design Theory course taught by a faculty member and an advanced graduate assistant during Spring 2019. Out of the eight students enrolled in the course, six of us (learners) opted to participate in the study. The faculty member and advanced graduate assistant provided guidance as mentors (e.g., answer questions, research design, review manuscript) but were not involved in the reflective elements, data collection and analysis, or framing of the findings. Through a variety of application assignments and reflective in-class discussions, we reflected on ID theory and its application. As individuals with diverse instructional design, professional, and educational backgrounds, our narratives, detailed prior to the Findings section, provide an overview of our background and experiences.

Data sources and collection

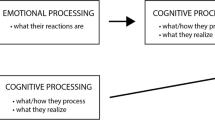

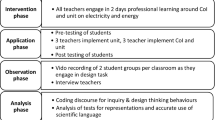

Chang et al. (2013) recommended using multiple data sources in CAE, including personal memory, archival materials, self-reflection, self-analysis, and group conversations, to add rich description and enhance credibility. In line with Chang et al.’s (2013) description of concurrent collaboration, our process (see Fig. 1) afforded us the space and time to develop individual perspectives without the influence of other team members by moving between group work and individual meaning-making experiences during data collection. As such, we were able to value our individual voices at the point of convergence in our focus group sessions.

Focus group transcripts

Learning from the experience of others was integral to our inquiry. We met for two in-person group discussions to consider our understanding of theory and our process of sensemaking. These focus group conversations occurred without the instructor(s) present and were recorded and transcribed for later analysis. The first two-hour session occurred on March 28, 2019, and included a collaboratively developed set of guiding questions (Appendix 1). Since CAE studies with more than two researchers are complex (Chang et al., 2013), this semi-structured format allowed us to freely express our thoughts while staying focused on the guiding questions.

Prior to this first session, we uploaded two documents into a shared folder: (a) our initial conception of ID theory assignment, presented as a visual with descriptive content, and (b) our mid-semester assignment in which we reflected on, revised, and described changes in our initial conception. Individually, we reviewed both documents, taking notes, looking for patterns, and developing an initial analysis which was then presented to the group. Comparing and contrasting changes in these assignments, individually and collectively, illuminated similarities, differences, and areas of growth which allowed us to value our individual voices within the CAE process (Chang et al., 2013).

The second two-hour focus group was held on April 10, 2019. Prior to this meeting, each group member considered potential themes in light of each other’s individual analyses from the first meeting and potential questions to guide the final reflexive narrative. The result of this focus group was a shared document in which we combined our thoughts on the reflection questions and negotiated the final set of questions to ensure the reflexive narrative prompts were representative of our collective experience with theory.

Reflexive narratives

We used the negotiated prompts from the second focus group to individually compose a narrative reflection of our personal sensemaking process (Appendix 2). This narrative allowed us to capture our individual theoretical sensemaking process based on course activities, focus group conversations, and personal reflections. As a result of these activities, our reflexive narratives became the main source of data which we subsequently analyzed to discern similarities, differences, and emerging patterns.

Data analysis

While the collaboration model of CAE includes participation of all researchers through the data collection, analysis, and reporting processes (Chang et al., 2013), we negotiated the division of these research tasks. Despite this division, we continually sought to represent all voices through in-person and virtual conversations, allowing individuals to confirm, contradict, or suggest revisions.

Two individuals (Holly and Tadd) engaged in successive cycles of independent and collaborative analysis following Chang et al.’s (2013) iterative three-step process. First, they independently reviewed the reflexive narratives, becoming familiar with the data and gaining a holistic view of individual and shared sensemaking experience. This experience allowed them to consider potential patterns and themes which may transcend individuals’ experiences or singular reflection prompts.

Second, Holly and Tadd deductively coded each reflexive narrative according to the reflection prompts developed by each of us during the second focus group meeting (see Appendix 3). After independently coding each reflection, they compared individual analyses and revised until full agreement was reached. These conversations also prompted discussions on emerging themes that would be considered later in the analysis process.

Next, to identify emerging patterns, Holly and Tadd independently analyzed and re-coded the reflexive narratives (at a sentence-level) and collaborated on emerging themes after each data category was coded until full agreement was reached. A codebook of deductive and emerging codes was created. In some cases, these codes transcended original data categories while other codes remained within the original structure. Finally, they reconnected the codes with the data by reviewing and re-coding each reflexive narrative using the final codebook (Appendix 4). Negative or contradicting cases were sought so all data would be fairly represented in the final analysis. Finally, they wrote drafts of the results which were reviewed regularly by the full group to ensure accurate representations of our experiences.

A second team, Mohan and Sally, reviewed the focus group transcripts. The detailed conversations from the focus groups enriched the individual reflections by providing evidence of our developing understanding of theory and how peer interactions facilitated that process. Mohan and Sally categorized segments of the focus group conversations according to each of the themes identified in the final analysis of the reflexive narratives. Next, each updated theme was reanalyzed by at least two of us. We reviewed the second set of findings to discuss discrepancies until full consensus was reached and adequate representation of each theme was achieved.

Trustworthiness

To resolve concerns of subjectivity inherent in CAE research, we included several trustworthiness checks as described by Lincoln and Guba (1985). To ensure credibility of the findings, we triangulated our experiences by engaging in multiple reflective activities culminating in a final reflection. Throughout data collection and analysis, member checking occurred frequently. We met to discuss the preliminary analysis and reach consensus on the final themes and sub-themes, and we revised the results to properly represent our individual experiences. Negative cases were also sought and incorporated in our findings to ensure that each of our perspectives were represented fairly and to highlight the diversity of our experiences. This member checking process ensured that each step of the analysis and writing process proceeded after group consensus was reached.

Researcher-participant narratives

Prior to describing our findings, we share our individual narratives to provide additional context and nuances of our individual sensemaking experience.

Holly

As a full-time instructional designer with two degrees in educational contexts, I questioned what ID theory was as I never heard about it through my prior education or job. I vividly recall asking the instructor in class, “What is ID theory?” She responded with, “I don’t know. What do you think ID theory is?” At that moment, I questioned my understanding of ID theory, with my struggle getting worse before it got better. Additional conversations with peers caused me to question a lot of ideas and terminology but pushed me to construct my own understanding of ID theory. Since the field of education primarily deals with human subjects, there is no right or wrong way to understand a phenomenon that occurs in the learning process and the same can be said of ID theory.

Mohan

I had two years’ experience as a secondary teacher and two years’ experience in training and e-learning design as a PhD student before this course. My prior experience led me to a mixed feeling of doubt and uncertainty of theory, especially when I saw the gaps between theories and practice. Despite my frustrations with theory from time to time throughout the course, I did have some “aha” moments along with my perception of theory being challenged, complicated, deepened, and altered through engaging in the readings, visualizing personal understanding of theories, and conversations with peers. The struggles and my developed mentality of living with such struggles motivated me to keep learning and exploring the nature of theory with a more holistic picture.

Nathan

Despite previously completing a handful of graduate level Curriculum and Instruction courses, this was my first course upon officially transferring into the ID doctoral program. With a science and agriculture background and an interest in integrating my education into my work at the university, my prior graduate experiences focused on engineering and engineering education. As an introduction to the ID program, I appreciated the course’s broad yet deep examination of ID theory and its many associated problems. Not surprisingly, early on I found myself struggling to make many necessary connections due to my lack of experience in the academic field of education. This familiar feeling has been endemic across my varied technical studies, and I have learned to cope with it over the years. I believe my tolerance for vague and seemingly conflicting concepts helped me avoid feeling overwhelmed by the inherent disagreements and inconsistencies within ID theory, and to make sense of what information was available from a variety of sources.

Sally

I entered this course as a full-time professional transitioning from an online master’s program in ID to the on-campus doctoral program. I have an MS in curriculum studies and varied work experiences, including teaching and developing professional training programs. I was confident in my abilities to succeed, so I was frustrated when I hit a wall 2 weeks into the course with the concept of prescriptive theory. This was not how I conceived of theory. I struggled to synthesize sometimes contradictory details, like scholars’ uses of various terms for the same idea. I wanted to know the difference between a theory, model, and framework and how each of these could be used in practice. Reading about design theories in other disciplines helped me grasp the contextual and interpretive nature of ID theory. The opportunity to engage in detailed discussions with my peers about their interpretations and struggles was, and continues to be, a critical part of my growth.

Tadd

As a former social studies teacher taking one of the last courses in my PhD instructional design program, I felt significant pressure to become a contributing member of scholars and practitioners within the instructional design community. I viewed my meaningful engagement with this community to be conditional on my understanding of theory, and I grew uneasy when significant gaps in my theoretical knowledge appeared. These gaps were particularly evident when my peers began asking questions that I was unable to satisfactorily answer. While my sensemaking process resulted in a deeper conceptual understanding of theory, I admitted that theoretical ambiguity will likely always be present, and that clear-cut and well-defined schemas are likely not the reality in the field of instructional design.

Yishi

My prior graduate experiences focused on student affairs in higher education. I was familiar with learning and development theories, but I had no idea about what ID theory was. I struggled to see a clear line between learning theories and ID theory, and I was easily able to fully take researchers’ definition and interpretation of ID theory. The class discussions, focus group meetings, and the instructors’ scaffolding helped me close the gap and develop my theoretical understanding. More importantly, I started to realize that there may not be a perfect answer for ID theory, and I finally found a suitable point to connect my own interpretations to ID theory.

Findings

We acknowledge the individual differences in our sensemaking process and the ultimate outcomes of our sensemaking activity. However, our experiences with sensemaking intersected in meaningful ways, allowing us to draw themes from shared experiences. While literature refers to novices, instructional designers, and graduate students, we refer to ourselves hereafter as learners with the understanding that no single label adequately describes our diverse roles and identities. As noted in the narratives, our experience with theory was individual; we differed in our previous experience with theoretical ideas, how our process began and evolved over time, and in our motivation for further understanding. Despite these differences, similarities in our sensemaking process were revealed, allowing us to discern patterns and commonalities as described below.

Theme 1: early theoretical understanding is largely basic and perfunctory

We found our initial understanding of theory was based on foundational course readings and information provided by the course instructors. For example, in his final course reflection, Tadd stated, “I knew the basics of what I should say; I had the words from other experts and I could regurgitate them in some way that made sense”. He added, “this early definition wasn’t really my own, but the words of others who I trusted”. Sally described her experience of defining theory as, “I included all the important component parts [of theory] as explained in the text and other assigned readings”. Additionally, Mohan stated, “My understanding of theory was constrained by my limited knowledge in the beginning… The limited understanding of theory purely came from a chapter of the textbook”. Initially, we lacked confidence in our own understanding or definition of theory as described in the following focus group conversation:

- Yishi:

-

I’m the student who changed dramatically in my second reflection. My first reflection was merely a summary of the readings, which didn’t represent my understanding of ID theory; therefore, I intended to create a completely new one to show my increased understanding of the theory.

- Mohan:

-

Could I ask you a question on the issue?

- Yishi:

-

Yeah.

- Mohan:

-

So, when you created your first assignment, you said you basically summarized the readings. Can I ask the reason? Was that because the rubrics were not clear?

- Yishi:

-

No, it was because of my limited knowledge in the theory field. It’s like I didn’t trust my understanding of theory, I didn’t know if my interpretation was correct or wrong. I relied heavily on the textbook, because I believed the textbook is 100% correct, I only wanted to summarize what the textbook told me.

- Tadd:

-

I think what you just brought up, I think I saw it in a lot of our first reflections in that they were repeated from reputable sources. Mostly regurgitating what ID is. So, we borrowed someone else’s, hijacked people’s definitions to try and define it ourselves, with very little synthesis.

With limited exposure to complex ID theory prior to this course, we initially relied on highly regarded resources (e.g., articles, books, researchers) in describing ID theory, with minimal early effort to synthesize these ideas in a meaningful way.

Theme 2: theoretical understanding is preceded by an awareness of insufficient knowledge

During our sensemaking process, we each described an awareness of our inadequate theoretical understanding. Tadd expressed this by saying,

Part of the theoretical sensemaking process is being confronted with gaps in my understanding. I think it’s fairly easy to know what I know, but it’s much more difficult to know what I don’t yet know. So, at some point, in trying to understand theory I have to be pushed off-balance, forced to consider things I never previously considered or forced to consider them in a different way.

Sally also alluded to her cognitive stasis when she reflected, “I was frustrated because despite all this information, I just didn’t get it… the feeling of disequilibrium was really on the fringes of every part of the process”. Yishi referred to “gaps” in her understanding when she said,

Honestly, I don’t like the feeling of struggle in my overall knowledge construction process because it makes me feel frustrated, but I’m very willing to embrace the struggles because I know they are the evidence to demonstrate my deficiencies. These struggles motivate me to do self-reflection to find the gaps in my knowledge and develop my understanding of theory.

Mohan described this experience of not knowing when he reflected, “Like I mentioned… there were multiple struggles, or questions that I was not able to answer, and I probably cannot provide a good answer even now”. Nathan mentioned more personalized influences which brought him to the “edge” of his understanding and created a subsequent need to act:

Through pursuit of personal interests, many of my courses covered material both outside of my primary field and at or beyond the edge of my understanding or experience, which in turn generated a compensatory need to self-remediate. Many years later, as a graduate student in engineering, I again found myself immersed in topics that were at or beyond the limits of my experiences and dependent upon knowledge that had long since become dormant through disuse, again requiring active remediation efforts to compensate.

Our peers played a role in helping us identify our insufficient theoretical understanding through formal and informal conversations. Yishi noted, “I like this step [observing her peers] because it helps me find many aspects regarding the theory that I missed or … I didn’t even realize I missed until I listened to my classmates’ perspectives and read their narratives”. Tadd reflected:

I can’t describe exactly when or how my struggle began but I think a lot of it had to do with hearing the verbalized struggles of my peers. I usually try and appear confident in my work but when I heard others talk about their questions regarding theory, I realized I shared many of these same questions. And when some of my peers asked questions that I didn’t have an answer to, that helped reveal gaps in my theoretical understanding.

Additionally, our early, limited theoretical understandings were influenced by the design of the course as reflected in a focus group conversation:

- Yishi:

-

I want to know if there’s a very clear line between ID theory, learning theory, and ID models—just like black and white. Another question is, I know that theory’s sensemaking process is very individualized, but are there any proper scaffolding that we can receive from more knowledgeable people to help develop our theoretical sensemaking process?

- Sally:

-

I will say that we keep being pressed to come back to defining what an ID theory is. So, maybe that’s part of why we struggle. Because we’re being asked to continually address that question. So would we struggle if we weren’t asked to make that distinction? If it were a different format? I don’t know.

- Yishi:

-

It’s been a challenge.

- Holly:

-

Right and that goes back to the concern I have, I don’t know how to say it….I think that’s kind of a teaching strategy, right? You want to build learners to develop their own thoughts, to have their own ideas and things like that. So is it good to set up a course like that, where you have everybody talk about what they’re doing, or is it better just to say, “This is what an ID theory is. Let’s move on”.

Individual and group reflections and discussions about the design of the course led to our realization that our understanding of theory was incomplete. We perceived a need for additional remediation to reach a more desirable level of understanding.

Theme 3: theoretical understanding is constructed using various approaches

As learners, our sensemaking experience shifted from a simple, initial understanding of theory to the edges of our knowledge and abilities, leading us to adopt a variety of approaches to achieve our desired levels of understanding. We use the word approach to describe our methods for making sense of theory, although these were not necessarily intentional or conscious activities but rather became identifiable retroactively as we reflected on our sensemaking experiences.

Deconstructing theory

During sensemaking we often deconstructed complex theoretical ideas into smaller, more comprehensible concepts. This allowed us to focus on basic, familiar concepts underlying theoretical ideas and use them as a foundation for greater understanding. For example, Holly noted:

I'm one that likes to break things down. So, I’m very much, ‘What are the pieces? How do they fit in this thing?’ And when you put these things together that’s what you get. So, I’m very much a component person, understanding the pieces then it can help me.

This tendency to focus on the constituent parts of theory was echoed by Sally when she said, “I was careful to check all the boxes in my definition as well as in the visual representation of ID theory... I included all the important component parts as explained in the text and other assigned readings”. Mohan also mentioned the same course assignment in which he used the “main characteristics of ID theory from the assigned readings”. The complexity of theory seemed unmanageable to us without first breaking down theories into more familiar concepts.

Despite the value of this deconstruction process, some of us acknowledged its shortcomings. Sally said, “trying to make sense of ID theory by breaking down the component parts was of limited value”. While breaking down theory allowed Sally to have an organized schema, the prescriptive nature of theory failed to fit her analytical approach. She reflected, “I was taking really detailed notes on all the readings, trying to pull it all together. I had this really organized concept of how all this fit together”. Tadd, likewise, observed a limitation in this approach:

Maybe this is just a question to throw out, I don’t know if we can really define something by just explaining the pieces of that thing. Can we define a car, by just describing it’s got tires? Or by the function of which the car serves? Because I don’t remember seeing a lot of descriptions of what theories, instructional design theory does. At least not as much as the descriptions of the characteristics of theory.

When new information did not fit, other sensemaking approaches were needed. Rather than only deconstructing, Holly mentioned a tandem use of approaches: “I try to break the information I learn into simple terms (e.g., theory, model, and framework) and then combine the terms with my own pre-existing schema”. While we often used this approach to understand complex theoretical ideas, it alone was not sufficient for developing deep theoretical understanding.

Distinguishing terminology

To understand complex theoretical concepts, we often sought to understand the boundaries of theoretical principles and their relationships to other ideas. This process involved comparing and contrasting concepts that appeared similar or interchangeable, and appropriately situating these related ideas within a larger theoretical conceptualization. Yishi noted that after she had a basic understanding of ID theory, she “began to construct my own knowledge and wanted to know what makes ID theory different from learning theory”.

While some of us sought clear boundaries between theory and related terms, Nathan stated, “Soft boundaries allow for malleability where firm boundaries may create barriers to mental change”. Perceiving ideas as “fuzzy” allowed Nathan to adapt his understanding when new information became available without requiring major revisions to a rigid cognitive structure. Still, some of us questioned the value of distinguishing terminology within the ID field. Mohan admitted, “It makes me wonder what is the point of our effort in making sense of theory if [distinguishing theory] is something the experts don’t even think about or... just don’t think it necessary to distinguish them”. Yishi agreed, stating, “Some ID theories are also understood as models, so do we really need to have a very clear line between these three things?” Despite the efforts some learners took to distinguish terminology, some learners questioned their ability or the value of making clear theoretical distinctions.

Integration with previous understanding

Early in our sensemaking process, we compared newly introduced theory with our previous understanding. Sally wrote, “Does this make sense based on what I already know? (Hint: The answer to this was typically ‘No’)”. Additionally, Nathan noted the influence of his pre-existing understanding in making sense of new theories but admitted that this influence may limit his potential understanding. As a result, Nathan purposefully “suspended” judgments of theoretical worth and value “prior to receiving all presented facts and conditions”.

Holly noted that while she had not used ID theory explicitly as an instructional designer, her developing theoretical understanding provided justification for her earlier design decisions:

When I am presented with new theories (learning, ID, or other), I try to combine my new knowledge of these theories into my pre-existing schema I already have in terms of design choices or decisions I made in the past. This connection to past events, adds meaning or justification to why or how I made those decisions unknowingly. In a way, it is a backwards learning process.

Openness to multiple perspectives

While our early theoretical understandings focused on the explanations of experts, over time, we described an increased openness to other perspectives and the acceptance of contradictory perspectives within the ID field. Sally noted that “actively exploring the perspectives of my peers was a critical part of the sensemaking process”. Interestingly, after she had “embraced uncertainty” and “let go of the need to approach ID theory from a logical, problem-solving perspective” she found more value in the perspectives of others. According to Mohan, “The perspectives from my peers enlightened me to look at ID theory from different angles, which could encourage me to think out of the box”. Repeated conversations with peers allowed his understanding to progress through a “collision” of ideas.

Our dynamic sensemaking process was influenced by multiple and sometimes contradictory perspectives in the ID field. Yishi perceived “different voices about one same thing” when reading two contrasting articles in preparation for a class discussion on the influence of instructional media. These contradictory voices helped her realize the potential for multiple perspectives in her theoretical understanding. Likewise, Mohan observed that “theorists themselves looked at the same thing from totally different angles”. Despite these contrasting perspectives, the intentional course design by the instructor allowed for student-led conversations that allowed Mohan to keep an open mind during “the open discussions”.

Personalizing understanding

We often formed our own individualized interpretations of theory to overcome challenges caused by complex and inconsistent theoretical ideas. After learning about descriptive and prescriptive theories, Yishi said, “I began to construct my own knowledge”. Her comments illuminate enhanced understanding from earlier experience in which her limited confidence “made me not trust myself to do the critical thinking about theoretical construction in my way”.

For some, personalizing theoretical understanding seemed to improve knowledge by reducing inconsistencies and providing clarity to complex theory. Nathan labeled this personalizing approach as “localizing”. Noting a fairly consistent struggle with theory that also “tapered somewhat toward the end”, Nathan wrote,

The significance of these issues lessened as theories and concepts became more internally well-defined and began to interconnect through shared understandings. Localized interpretations began to develop and helped me to compensate for unresolved inconsistencies and vagueness in terminology and related issues. I still need to work on bridging between my own and other’s interpretations, but that is something I expect to develop through further personal investigation and sensemaking.

While Nathan noted a need for continued investigation, this personalized understanding assisted him in developing a deeper understanding of theory through “meaningful resolutions” to perceived theoretical inconsistencies.

Application of theory

Our theoretical understanding was enhanced by searching for ways in which theory could be applied. As a full-time instructional designer, this approach was vital for Holly, “I need to understand the importance of the theory. Why is this theory needed? What is this theory trying to explain? How does this theory link these specific conditions, principles, environments…?” Additionally, Holly worked to “understand how theory makes sense to me in my specific context and how it should be valued moving forward”. Sally also saw a need for contextual understanding: “I think we need both. I mean we do need to understand the parts, but we need to understand in what context they're situated in and what influences them”. While Holly and Sally reflected on context, Mohan sought clarity through examples: “Yeah so for me, I definitely need to see the example. So, if you tell me, ‘this is the theory,’ I need to see how it is used”. For some of us, increased understanding of complex theory required actual application of theory in practice or clear examples or ideas of how theory could be used in authentic contexts.

Theme 4: theoretical understanding involves struggle

Struggle, the emotional and intellectual work associated with complex learning, was an important part of the sensemaking process we all mentioned. While different factors contributed to our individual struggles with theory (e.g., unclear terminology, complexity, course-related factors), we described different roles and purposes of struggle in our sensemaking process.

Struggle as a necessary experience

For some of us, struggle was a crucial experience in our sensemaking process. Holly noted, “In order to make sense of something, one must really struggle or work through the process of actively learning something…If not struggling to understand something, are you truly figuring it out?” Tadd agreed, commenting that “I would say that struggle is the required cost associated with understanding; I just don’t know if you can understand theory in any sort of actionable or useful way without engaging in this struggle”. Specific to the course, Holly added:

The idea of the struggle and us having trouble making sense of it, this is where I started to view this process as good because I felt like because of this class we’re now able to question everything. I think there’s some benefit to being a good researcher or a good instructional designer and being able to question what’s out there and not accept the answers and move forward and forge your own path... I viewed our ideas of struggling with this to be really beneficial to us as future researchers, as future whatever we want to be.

Despite the difficulty, some of us embraced the struggle. Yishi reflected, “Honestly, I don’t like the feeling of struggle in my overall knowledge construction process because it makes me feel frustrated, but I’m very willing to embrace the struggles because I know they are the evidence to demonstrate my deficiencies”. Mohan also admitted that “frustration did exist during this process” but viewed it positively:

What is wrong with struggling? I think one that I can definitely take away is even though by the end of this research, even though it’s published in a top journal, I will still be confused. But I will have a much better understanding of ensuring the design... whether it’s approaches or models. But how to use it. How to select the appropriate approach to get my practice.

However, as opposed to circumventing struggle, he described attempts to face it head-on: “Rather than trying to avoid the struggles, I think it’s better to embrace them because of the positive side of being struggling a little bit in making sense of theory”.

Struggle as motivation

Albeit frustrating, struggle also motivated us to take action to further our understanding of theory. Mohan expressed, “The struggles did not stop me from moving forward. Instead, these struggles have been the motives for me to learn more, talk more, and explore more”. Similarly, Nathan stated, “I find the role of struggle in understanding theory is similar to the role of struggle in most complex learning. Struggle provides a recurring reminder that your understanding is incomplete and in need of refinement”. However, Nathan also noted a need for balance:

While excessive struggle may demoralize and frustrate some learners more than others, struggle that is maintained just along the edge of understanding… should entice those with an interest in a topic to strive further than they may otherwise if given a sense of premature mastery.

While not explicitly stated as a motivation, Nathan described a positive effect of inadequate knowledge on his sensemaking process. We viewed our struggle as an inextricable part of developing deeper theoretical understanding.

Discussion

In the early stages of the course, articulating our understanding of instructional design (ID) theory was a challenge, largely focused on a search for the “right” answer. With ample resources regarding ID theory, we demonstrated an overreliance on prominent experts and a lack of confidence finding our own voices. Noting the difficulty of understanding theory, Bostwick et al. (2014) found that in the early stages of a course, graduate students examined theories in much the same way we did—by defining and paraphrasing terminology. The authors noted that the process of developing critical understanding was “painful”, often invoking a sense of “dismay” (p. 576).

While Bostwick et al. (2014) suggested that the relative newness of the ID field and continuing evolution of theories may be sources of struggle, Meyer and Land’s (2006) notion of threshold concepts offers additional insights. Threshold concepts are core concepts that are particularly transformative for learners’ intellectual development and represent knowledge that is conceptually difficult. Meyer and Land (2006) describe an in-between stage of liminality in which learners may feel stuck. Like our early attempts to understand ID theory, during this liminal stage learners often encounter periods of uncertainty, confusion, frustration, and self-doubt, and present superficial understandings through mimicry. In an investigation into threshold concepts, Kiley (2009) conducted surveys and interviews of 45 doctoral supervisors and concluded that the concept of theory is one of six threshold concepts with which learners struggle. Rowbottom (2007) points out, however, that “what counts as threshold is agent-relative” (p. 267) and that perhaps these concepts are not necessarily relevant for all. This variation can be seen in our own diverse perspectives and approaches to understanding ID theory.

While we experienced different levels of liminality (Meyer & Land, 2006), our individual sensemaking processes contributed to our developing understanding of ID theory. Weick et al. (2005) noted that sensemaking becomes an explicit effort when learners are confronted with a current state that differs from their expectations. While Weick et al. (2005) focused on sensemaking in organizational theory, the concept has also been applied in education. For example, Rapanta (2019) proposed that there are certain instructional approaches that can facilitate learners’ sensemaking. Individual constructivism can help support learners’ development of personalized understanding. Using a social constructivist approach, an instructor can assist learners in articulating and refining meaning in collaboration with others. Finally, socio-epistemological approaches help learners make sense of themselves “through their authentic participation in social discourse and the constant negotiation of their learning goals, ideas, and identities” (Rapanta, 2019, p. 48). Associated with these approaches is the necessity of uncertainty (Rapanta, 2019), a feeling many of us encountered in our sensemaking process.

Early in our theoretical sensemaking process, we looked for accurate interpretations we could adopt. As the course progressed, we grew dissatisfied with our superficial understanding and wanted to better articulate ID theory and understand it in practice. Sensemaking is a retrospective process (Weick et al., 2005), and while we viewed making sense of theory as essential, our experience aligned with previous research indicating a potentially overwhelming and lengthy process (Burri, 2017). In order to alleviate the discomfort or anxiety associated with facing complex concepts (Grimmett, 2016), we often sought out direct answers from our instructor. However, our instructor intentionally used instructional strategies that helped us interpret, reorganize, and construct our own understanding of theory in a meaningful way.

Reigeluth (1984) offered a relevant analogy to how we used various approaches to construct our theoretical understandings. He suggested that different theories each provide a partial understanding of reality: “Some theories look at the same room through different windows (i.e., from different theoretical perspectives), while others look at completely different rooms (i.e., different instructional objectives)” (p. 21). In developing their understanding of ID theory, students must learn to look at different rooms through various windows, and at the same room from more than one window. From our own sensemaking experiences, we came to understand that each person may peer through different theoretical windows, and that a person’s perspective may change over time. Thus, we realized that multiple approaches are needed to construct a comprehensive understanding of ID theory.

While our sensemaking processes helped deepen our understanding of ID theory, we also acknowledged the struggles we encountered along the way. Reigeluth and Carr-Chellman (2009) noted that inconsistency in ID terminology may contribute to graduate students’ confusion, which aligns with our findings as a primary source of our struggle. Therefore, our findings support the contention that learning how to deal with ambiguity and struggle can benefit novices facing challenges (Belcher & Hirvela, 2010); we viewed struggle as both necessary and motivating.

Once we moved beyond our initial state of uncertainty, our recognition of the gap between our theoretical perceptions and expectations encouraged us to reflect on our sensemaking process and question ourselves, both individually and collaboratively. By exploring our own and others’ perceptions, we each developed approaches and strategies that allowed us to deepen our understanding of ID theory. In line with the retroactive nature of sensemaking (Weick et al., 2005), we recognized that our sensemaking relative to ID theory was a process of acquisition, reflection, and interaction that would continue as we develop expertise.

Implications

This collaborative autoethnography investigated the theoretical sensemaking processes of instructional design (ID) doctoral students and has implications for learners, instructors, and researchers. As learners struggle to make sense of theory, self-reflective practice can lead to developing ID expertise. Bochner and Ellis (2006) stated, “autoethnographies show people in the process of figuring out what to do, how to live, and what their struggles mean” (p. 111). While we did not consistently embrace the struggles associated with theoretical sensemaking, our experience illuminates the potential benefits of self-reflective practices (e.g., reflexive writing, group discussions) to ameliorate the detrimental effects of struggle. Self-reflection deepens theoretical understanding (Kapa, 2007), and the practice of reflecting on personal understanding can help to strengthen metacognitive skills and improve problem solving (Garrison, 2003). Therefore, learners should use intentional self-reflection practices (e.g., journals, blogs, informal conversations, concept maps) to strengthen their skills and knowledge in the development of individual expertise which takes time, practice, and awareness of experts’ thought processes (Burri, 2017; Casanave & Li, 2015; Ertmer & Stepich, 2005).

Our findings revealed the need for instructors to prepare learners to embrace the role of struggle in the sensemaking process by exposing students to complexity and supporting learners’ struggle and sensemaking processes through reflective practices and within course design. As learners demonstrate early perfunctory conceptual understanding, instructional practices can be used by instructors to increase complexity to build on learners’ existing understanding (Casanave & Li, 2015; Yanchar et al., 2010). Additionally, instructors can support learners’ struggles by providing a range of instructional activities (e.g., reflection, modeling, role play) when teaching to accommodate learners’ diverse approaches. (e.g., deconstructing theory, distinguishing different terminologies). Instructor flexibility is also important, as exemplified in our study. Rather than the final individual paper that was required in the course syllabus, our instructor allowed us to investigate this phenomenon as a collaborative research project. Her support empowered us to own our learning process and extend our understanding in personally meaningful ways.

For those responsible for course design, Winn (1997) stated a need for theory courses to require an application piece to help prepare instructional designers for work in the field. Such applications could include intentionally designing with theory in mind, using real-world clients, and providing service-learning opportunities among other course activities. Our findings can help graduate programs consider course changes (e.g., order of courses, prerequisite knowledge, instructional activities) or additions to program curriculum (e.g., theory-focused application courses) to help learners deeply understand theory. Specific to instructional strategies, our views expressed in the sensemaking process (e.g., struggle, disequilibrium) align with transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1994) which allows “learners [to] interpret and reinterpret their sense experience” (p. 222). Therefore, reflexive elements (e.g., journals, reflections, informal conversions) can be implemented to help learners develop their own understanding and apply theory in their own setting.

While this study investigated our process of understanding ID theory, our experience may be similar to other advanced learning. More research is needed to understand how, if at all, these findings are shared in other complex learning environments. How do learners, confronted with complex learning, progress from a state of unfamiliarity and nescience to a state of mastery and competence? What is the role of struggle during this process within these different learning environments? Furthermore, as ID research continues to be developed and advanced, we hope our study promotes a renewed call for greater clarity in the ID field by encouraging researchers to carefully consider their use of theoretical terminology and ideas.

While we believe our investigation provides an interesting and relevant view into the developing theoretical understanding of learners, this study is not without limitations. As an autoethnographic approach, the data stems from our personal experiences and is subject to our own biases and interpretations. Additionally, limitations of time and resources prevented us from fully collaborating on each stage in the research process. In our study, we sought to minimize the impact of these limitations by utilizing various sources of data from multiple individuals which enabled us to consider perspectives beyond our own. Negative case analysis and member checking helped maintain credibility by minimizing the dominance of a small number of voices and ensuring that each perspective was accurately represented in our findings. This study may not and was not intended to be completely generalizable to other settings. We acknowledge the impact of our individual characteristics, experiences, and the uniqueness of our shared learning culture on this investigation. We have sought to richly describe these factors to provide transparency in our methods, findings, and conclusions. We encourage others to likewise investigate the theoretical sensemaking experience of learners and designers in other settings to determine how these findings may be unique or shared across institutions and cultures.

Conclusions

Although our theoretical understanding process was never effortless, we recognized an accurate and actionable understanding of theory is needed by instructional designers to design and facilitate effective learning experiences. Despite its central role, theory is challenging for learners to understand due to unclear and inconsistent presentations of theory, the complex and abstract nature of theory, and the separation of theory from practice. To better understand how learners make sense of theory, we utilized a collaborative autoethnographic approach as we investigated our sensemaking process within an advanced graduate instructional design theory course. Moving recursively between individual and shared perspectives, our inquiry revealed that our initial understanding of theory was largely contrived from the unsynthesized ideas by experts in the instructional design field. Recognizing our individual sensemaking process was contextual and situational, our insufficient theoretical understanding led us to engage in various approaches to remediate the gaps in our knowledge and develop a more comprehensive view of theory. These approaches varied by individual and often occurred unconsciously throughout formal and informal learning activities. Sometimes the newly assimilated information conflicted with our current mental structures, which made us recognize a cognitive imbalance stage where feelings of struggle punctuated our sensemaking process, especially as we wrestled with individual and shared concerns in our pursuit of greater understanding. Although difficult to bear, we came to view this sense of struggle as an important, even essential, part of our sensemaking process.

References

Belcher, D., & Hirvela, A. (2010). “Do I need a theoretical framework?” Doctoral students’ perspectives on the role of theory in dissertation research and writing. In T. Silva & P. Matsuda (Eds.), Practicing theory in second language writing (Second language writing) (pp. 263–284). Parlor Press.

Bichelmeyer, B., Boling, E., & Gibbons, A. S. (2006). Instructional design and technology models: Their impact on research and teaching in instructional design and technology. In M. Orey, V. J. McClendon, & R. M. Branch (Eds.), Educational media and technology yearbook (Vol. 31, pp. 33–73). Libraries Unlimited.

Bochner, A. P., & Ellis, C. (2006). Communication as autoethnography. In G. J. Shepherd, I. St. John, & T. Striphas (Eds.), Communication as … perspectives on theory (pp. 110–122). Sage.

Bostwick, J. A., Calvert, I. W., Francis, J., Hawkley, M., Henrie, C. R., Hyatt, F. R., Juncker, J., & Gibbons, A. S. (2014). A process for the critical analysis of instructional theory. Educational Technology Research and Development, 62(5), 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-014-9346-5

Burri, M. (2017). Making sense of theory: A doctoral student’s narrative of conceptualizing a theoretical framework. BC TEAL Journal, 2(1), 25–35.

Casanave, C. P., & Li, Y. (2015). Novices’ struggles with conceptual and theoretical framing in writing dissertations and papers for publication. Publications, 3(2), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications3020104

Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F., & Hernandez, K. A. C. (2013). Collaborative autoethnography. Left Coast Press.

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39, 2–6.

Christensen, C. K. (2008). The role of theory in instructional design: Some views of an ID practitioner. Performance Improvement, 47(4), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.20221

Ertmer, P. A., & Stepich, D. A. (2005). Instructional design expertise: How will we know it when we see it? Educational Technology, 45(6), 38–43.

Garrison, D. R. (2003). Cognitive presence for effective asynchronous online learning: The role of reflective inquiry, self-direction and metacognition. In J. Bourne & J. C. Moore (Eds.), Elements of quality online education: Practice and direction (pp. 47–58). Sloan-C.

Gibbons, A., & Rogers, P. C. (2009). The architecture of instructional theory. In C. M. Reigeluth & A. Carr-Chellman (Eds.), Instructional-design theories and models: Building a common knowledge base (Vol. 3, pp. 305–326). Routledge.

Grimmett, H. (2016). The problem of “just tell us”: Insights from playing with poetic inquiry and dialogical self theory. Studying Teacher Education, 12(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2016.1143810

Hardré, P. L., Ge, X., & Thomas, M. K. (2006). An investigation of development toward instructional design expertise. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 19(4), 63–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-8327.2006.tb00385.x

Johnson, E. C. (1998). The importance of theory. Teacher Education Quarterly, 25(4), 37–38.

Jonassen, D., Hennon, R., Ondrusek, A., Samouilova, M., Spaulding, K., Yueh, H., Li, T., Nouri, V., DiRocco, M., & Birdwell, D. (1997). Certainty, determinism, and predictability in theories of instructional design: Lessons from science. Educational Technology, 37(1), 27–34.

Kapa, E. (2007). Transfer from structured to open-ended problem solving in a computerized metacognitive environment. Learning and Instruction, 17(6), 688–707.

Kiley, M. (2009). Identifying threshold concepts and proposing strategies to support doctoral students. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290903069001

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey Bass.

Merrill, M. D. (2006). Hypothesized performance on complex tasks as a function of scaled instructional strategies. In J. Elen & R. E. Clark (Eds.), Handling complexity in learning environments: Theory and research (pp. 265–281). Elsevier.

Meyer, J. H. F., & Land, R. (2006). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: An introduction. In J. H. F. Meyer & R. Land (Eds.), Overcoming barriers to student understanding: Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (pp. 3–18). Routledge.

Mezirow, J. (1994). Understanding transformation theory. Adult Education Quarterly, 44(4), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171369404400403

Rapanta, C. (2019). Bewilderment as a pragmatic ingredient of teacher-student dialogic interactions. Studia Paedagogica, 24(4), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.5817/SP2019-4-2

Reigeluth, C. M. (1984). The evolution of instructional science: Toward a common knowledge base. Educational Technology, 24(11), 20–26.

Reigeluth, C. M. (1997). Instructional theory, practitioner needs, and new directions: Some reflections. Educational Technology, 37(1), 42–47.

Reigeluth, C. M. (1999). What is instructional-design theory and how is it changing? In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory (Vol. 2, pp. 5–28). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Reigeluth, C. M., & Carr-Chellman, A. A. (2009). Understanding instructional theory. In C. M. Reigeluth & A. A. Carr-Chellman (Eds.), Instructional-design theories and models: Building a common knowledge base (Vol. 3, pp. 3–26). Routledge.

Rowbottom, D. P. (2007). Demystifying threshold concepts. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 41(2), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2007.00554.x

Scandura, J. M. (1996). Role of instructional theory in authoring effective and efficient learning technologies. Computers in Human Behavior, 12(2), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/0747-5632(96)00010-6

Silber, K. H. (1982). An analysis of university training programs for instructional developers. Journal of Instructional Development, 6(1), 15–28.

Smith, K. M., & Boling, E. (2009). What do we make of design? Design as a concept in educational technology. Educational Technology, 49(4), 3–17.

Tamez, R. (2016). Theoretical frameworks of performance-based models. Performance Improvement, 55(6), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21592

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/0rsc.1050.0133

Wilson, B. G. (1997). Thoughts on theory in educational technology. Educational Technology, 37(1), 2–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44428382

Winn, W. (1997). Advantages of a theory-based curriculum in instructional technology. Educational Technology, 37(1), 34–41.

Wrenn, J., & Wrenn, B. (2009). Enhancing learning by integrating theory and practice. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 21(2), 258–265.

Yanchar, S. C., South, J. B., Williams, D. D., Allen, S., & Wilson, B. G. (2010). Struggling with theory? A qualitative investigation of conceptual tool use in instructional design. Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-009-9129-6

Zhang, P., & Soergel, D. (2014). Towards a comprehensive model of the cognitive process and mechanisms of individual sensemaking. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(9), 1733–1756. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23125

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Research involving human subjects or animals in research

All research complied with all relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies.

Informed consent

Informed consent for participation and publication of data was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in the article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Focus group 1 guiding questions

From: Tadd.

Sent: Thursday, March 28, 2019 11:33 AM.

To: Koehler, Adrie <akoehler@purdue.edu>; Meech, Sally A <sally@purdue.edu>; Hilliard, Nathanial C <nhilliar@purdue.edu>; Mohan Yang <yang1178@purdue.edu>; Yishi Long <long259@purdue.edu>

Cc: Fiock, Holly S <hfiock@purdue.edu>; Zui Cheng <cheng283@purdue.edu>

Subject: Re: REMINDER: Analysis of Documents.

Thanks all for your help. Sally, I think you’re exactly right. I’ve struggled with the idea of a focus group but I do like the shift to a “reflective group”. According to the article, it seems more like what we’e trying to achieve. A focus group seems to imply having a central moderator who leads and guides this discussion. Since what we’re trying to achieve is a student-facing project that emerges from our perspective, I think it may be problematic to have Zui or Adrie fill this role. I think they would do a great job, but I wonder if a potential reviewer might point to this as a possible limitation of our methods. What do you think?

So, I think what we have could be called a “semi-structured reflection group discussion”. We could have a simple semi-structured discussion protocol serve as our discussion guide (although it should probably be fairly open), and establish norms that all voices will be heard. Here’s a possible structure for this reflective discussion:

-

Part 1: Reflecting on group members’ understanding

-

What patterns or themes did you notice commonly across the data? (the rule)

-

What peculiarities did you notice among some reflections that you did not see shared commonly with other participants? (the exception)

-

What did you find missing in the reflections of your class members?

-

What changes did you perceive in group members’ understanding of theory from the first to mid course reflection?

-

-

Part 2: Individual sense-making process

-

What is your current understanding of theory?

-

How has your understanding of theory changed?

-

What questions are still lingering with regards to theory?

-

Appendix 2

Reflexive narrative questions

-

1.

What is your theoretical sensemaking process?

-

2.

What contributes to your theoretical sensemaking process? What factors contribute to this process?

-

3.

What is the role of struggle in theoretical sensemaking?

-

a.

Describe your personal struggle with instructional design theory (when did it start? What factors contributed to the struggle? How did it progress?)

-

a.

-

4.

How do you value the role of theory in instructional design?

-

5.

How has your understanding of theory changed through this sensemaking process?

Appendix 3

Initial codebook

Codes | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

Definitions of sensemaking (sm_define) | What sensemaking is or what it aims to achieve | Tadd—“To really understand or make sense of something, I need to have not only a knowledge of the concepts, but I also need to be able to use it in some actionable way” Nathan—“My process of theoretical sensemaking consists of five main components which allow me to deal with new information that I may not have the requisite background to fully process” |

Descriptions of sensemaking (sm_descript) | Details of how sensemaking occurs, or what it is like | Mohan—“Therefore, my sensemaking process was dynamically influenced by anything that I accessed throughout the semester, and I can see that it is still evolving” Sally—“The steps below describe my process, but these steps were not linear; in fact, they co-existed. For example, the feeling of disequilibrium was really on the fringes of every part of the process” |

Sensemaking process (sm_process) | Steps, parts, or elements of the process of sensemaking | Tadd—“So, at some point, in trying to understand theory I have to be pushed off-balance, forced to consider things I never previously considered or forced to consider them in a different way” Nathan—“After this isolated consideration, I then work to integrate what I have learned into what I already (think that I) know” |

Personal progress (meta_progress) | Acknowledgement of change (positive or negative) towards theoretical understanding | Yishi—“I’m glad to see my growth of theory understanding over the semester” Holly—“For a long time in this course, I did not find a connection between instructional design theory and an ID model... Over the duration of this course, through my own sensemaking process, I now know there is a clear difference between the two” |

Personal impact (meta_personal) | Realization of personal impact made by various factors on sensemaking; may include specific factors, but specifically acknowledge impact these had on them personally | Yishi—“Moreover, the prompts in reflection assignments helped me do self-check of my knowledge. These prompts were different in the initial and mid reflection, but they were connected closely, which guided me to sense my improvements as well as the discrepancies of my understanding” |

Personal attributes (meta_attributes) | Awareness of characteristics and/or qualities of individuals that help or hinder their theoretical sensemaking, including background knowledge and experience *While this could go with theme number three, we are prioritizing the meta-cognitive component over the factor characteristic. As long as this gets coded, we can change it later if we need to | Yishi—“I didn’t believe my understanding is correct, and I always wanted to have a perfect and 100% correct answer towards theory, like what math does” Nathan—“My emotional state, related to distractions, frustration, disdain, and discomfort will also limit the amount of focus, effort, and interest that I may apply to a given theory in a given situation” Mohan—“After seeing how other people did the pre-assignments, I sometimes interpreted the requirements a little bit differently and I am not sure whether that was because of language barrier or just the way of my thinking” |

Self-directed tasks (fact_self) | Influence of tasks and experiences pursued voluntarily by participants; independent research or study to achieve greater understanding | Sally—“Complete assigned readings, reflect and take notes, and find additional research to expand my understanding” Tadd—“I wrote that down and revisited that point on my own time. As I read through material I found related to that idea and tried to validate it, I determined that I still felt there was a difference between models and theories that went beyond prescriptive details” |

Peer influence (fact_peer) | Influence of peers on sensemaking through formal/informal discussions, peer review assignments, etc | Tadd—“When we got together in the group meetings to discuss ideas (the “other” experiences”), I found that some of my previously-held ideas about theory were validated or corrected, or I learned entirely new things from others and the synergy of that sharing experience” Holly—“at one point, I felt there was no such thing as ID theory. I now, however, believe that ID theory does exist. I was only able to come to this conclusion based on the amount of focus groups and discussions, both in class and out of class with my peers” |

Instructor influence (fact_instructor) | Influence of instructor on sensemaking through instructor interactions, feedback, etc | Mohan—“The active learning promoted by the instructor have been effective to us” Yishi—“I really like the facilitator role of my instructors to guide us to discuss what we learn from the readings. Without the scaffolding or facilitation in class, it will like “ok, I complete the required readings, then what?” |

Course influence (fact_course) | Influence of course factors on sensemaking, including class activities, assignments, required readings, and the course structure *While this undoubtedly includes many things, we’re going to keep them at this level and see what codes emerge from it | Nathan—“Similarly, if time is limiting then insufficient effort may be expended regardless of interest level” Tadd—“After we completed these reflections (self), my teacher gave us an opportunity to share in class what we had learned and listen to presentations given by other students (others)” |

Other influence (fact_other) | Influence of other factors not listed above | |

Current understanding (out_current understanding) | Details regarding current understanding of the nature and description of theory; also includes current lack of understanding towards theory | Holly—“Instructional design theories—prescriptive and probabilistic; create conditions (guidelines) to increase the probability of learning; because they are prescriptive they are able to provide guidance (this is more of the how)” |

Value of theory (out_value) | Explanations of the importance and significance in theory and theoretical understanding | Nathan—“I value theory in instructional design for the deeper understanding it provides for the rationale behind ID decisions” |

Role of theory (out_role) | Information regarding the utility of theory in research, design, and other related factors | Yishi—“I believe theory links different models and the selection of models really depend on the understanding of the theory behind them” |

Appendix 4

Final codebook

Codes | Definition |

|---|---|

Awareness of gaps | The prior knowledge or state of understanding at the beginning of this sensemaking experience. Often described as basic or superficial, this is the baseline from where an individual began the semester. While not a part of the sensemaking process, it’s important to note where the individual was when they began the sensemaking process |

Initial understanding | The feeling of lacking in knowledge or skill related to instructional design theory or its application. Some individuals become aware of these gaps through distinct events, while others perceive gaps more subtly |

Knowledge Construction or action | The awareness of gaps leads individuals to seek for information to overcome these knowledge gaps. Various tools are available to individuals to assist individuals to make sense of theory through the following processes |

Application | Attempts to see how theory could be applied to instructional design practice, or actual experience in using theory to design or develop instruction |

Breaking down Theory into parts | Attempts to understand theory by breaking it into basic concepts or ideas that can be understood more easily. This approach attempts to get at the essence of theoretical ideas |

Distinguishing terminology | Attempts to distinguish or differentiate terms related to theory, including theory, models, frameworks, etc. These attempts assist individuals in understanding theory by first knowing what it is not |

Integration with previous understanding | As new understanding of theory is gained, individuals seek to fit this new understanding into what was previously known about a topic. Some individuals refer to the construction or formation of knowledge schema in describing this step, while others speak of it more generally |

Personalized understanding | In an attempt to make sense of theory, individuals personalize their understanding of theory by forming their own interpretations of theory and related components, and localizing these definitions for their own purposes. It is unclear if this is a part of the knowledge construction process or if this is an integrative step |

Perspectives | Considering various perspectives on theory from others, including experts in the field, peers and classmates, and the instructor. Some individuals also view the need to develop one’s own perspective towards theory |

Reflection and self-evaluation | Reflecting on theory, either conceptually on one’s personal understanding of theory (i.e., personal assessment) |

Struggle | The feeling of work, frustration, and difficulty as part of the sensemaking process. Despite its unpleasant connotation, many individuals view the struggle as an important or contributing factor in greater theoretical understanding |

Other | Influence of other factors not listed above |

Rights and permissions