Abstract

Purpose

Cumyl-PEGACLONE was the first synthetic cannabinoid (SC) with a γ-carbolinone core structure detected in forensic casework and, since then, it has dominated the German SC-market. Here the first four cases of death involving its fluorinated analog, 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE, a recently emerged γ-carbolinone derived SC, are reported.

Methods

Complete postmortem examinations were performed. Postmortem samples were screened by immunoassay, gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS) or liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. For quantification of SCs, the standard addition method was employed. Herbal blends were analyzed by GC–MS. In each case of death, the Toxicological Significance Score (TSS) was assigned to the compound.

Results

5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE was identified at concentrations ranging 0.09–0.45 ng/mL in postmortem femoral blood. In case 1, signs of hypothermia and kidney bleedings were noted. Despite a possible tolerance due to long term SC use, a TSS of 3 was assigned. In case 2, an acute heroin intoxication occurred and a contributory role (TSS = 1) of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE was suggested. In case 3, a prisoner was found dead. GC–MS analysis of herbal blends, retrieved in his cell together with paraphernalia, confirmed the presence of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE and a causative role was deemed probable (TSS = 2). In case 4, the aspiration of gastric content due to a SC-induced coma was observed (TSS = 3).

Conclusions

5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE is an emerging and extremely potent SC which raises serious public health concerns. A comprehensive analysis of circumstantial, clinical, and postmortem findings, as well as an in-depth toxicological analysis is necessary for a valid interpretation and for the assessment of the toxicological significance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On the market for new psychoactive substances (NPS), synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) represent a class of designer drugs, which have been synthesized for recreational purposes to mimic the effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Thus, they are usually sold as ‘synthetic marijuana’ or ‘fake weed’ and claimed to be safe and legal alternatives to common illegal cannabis-based products, despite being potent full agonists at the cannabinoid CB1-receptor.

SCs are not only one of the most widespread classes of NPS, but also among the most structurally diverse. Despite the evolution of the different national and/or international legislations, novel compounds are synthesized and sold to circumvent the law and although the number of new compounds has dropped in the last years, their availability is still high [1].

Several different classes of SCs have been synthesized since the first appearance in 2008 [2, 3], including substances characterized by indole, indazole, or benzimidazole core structures [4]. Gamma-carbolinone derived SCs are characterized by a tricyclic core structure and first entered the market in Germany in November 2016, after the “Act to control the distribution of new psychoactive substances” (NpSG), which did not cover this type of structures until recently, came into force [5].

Particularly, 5-pentyl-2-(2-phenylpropan-2-yl)-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrido[4,3-b]indol-1-one (semisystematic name: Cumyl-PEGACLONE or SGT-151) was the first SC with a γ-carbolinone core structure detected in forensic casework and, since then, it has dominated the German SC-market [6,7,8]. It has indeed been detected in about 25% of herbal blends purchased in Germany during a monitoring program and has showed high prevalence in biological specimens [8].

Cases of deaths due or related to SCs are commonly reported in the literature, although the determination of the significance of toxicological results, as highlighted by Elliott et al. [9], can be difficult and often lacks. The Toxicological Significance Score (TSS) is a system developed to perform and strengthen the health risk assessment of NPS and to allow the clarification of the role of such substance(s) in deaths. On the basis of a comprehensive analysis, a score from 1 (i.e. Low, alternative cause of death) to 3 (i.e. High, NPS likely to have contributed to toxicity/death, despite the detection of other drugs) is assigned [9]. Six cases of death related to the intake of Cumyl-PEGACLONE were reported, in none of which, according to the TSS, the substance seemed to have played a causative role [8]. Due to the relatively low occurrence of severe intoxications and of deaths caused by Cumyl-PEGACLONE, the compound has been suggested as a “comparatively safe drug” and a relative “low toxicity” of SCs bearing a γ-carbolinone core structure was considered possible [8].

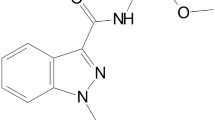

In 2018, following the introduction of Cumyl-PEGACLONE into the annex of the German Narcotics Law (Betäubungsmittelgesetz, BtMG), the fluorinated analog of Cumyl-PEGACLONE, 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE (5-(5-fluoropentyl)-2-(1-methyl-1-phenylethyl)-1H-pyrido[4,3-b]indol-1-one) was identified in our laboratory as the constituent of a “research chemical” and its metabolism has been studied by means of in vitro and in vivo studies [10]. Since then, it almost replaced Cumyl-PEGACLONE on the market, with a proportion of about 25% of the herbal blends analyzed in our laboratory, and was recently added to the list of controlled substances in Germany. In Fig. 1, Cumyl-PEGACLONE and its 5-fluoro analog are shown.

The binding affinity of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE to the CB1 receptors has not been yet studied, though a higher potency than Cumyl-PEGACLONE (1.37 ± 0.24 nM) [5] would be in line with fluorinated compounds usually being more potent than their non-fluorinated analogs [11].

Between the last months of 2018 and the first months of 2019, four cases of death, in which 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE was involved, were discovered in Germany. To the best of our knowledge, these are the first cases connected to this novel SC.

Case history

Case 1

In October 2018, a 37-year-old male was found dead in his apartment, wearing only a t-shirt and a pair of boxers. He had a past history of mental health disorders and cannabinoid use in harmful quantities. No obviously illegal substances were recognized at the scene, though pieces of papers and flasks probably containing e-liquids were not collected. The autopsy was performed 2 days after the retrieval of the corpse.

Case 2

A 48-year-old female was found naked in her flat in December 2018. The woman had a well-known history of narcotic drug and “Spice” product use, but no mental diseases or previous suicidal intentions were reported. Death scene investigation (DSI) provided no clues regarding a recent intake of SCs. The autopsy was performed with a postmortem interval (PMI) of 7 days.

Case 3

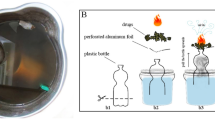

In January 2019, according to the report of the jail, a 36-year-old prisoner was found near his cell. Brownish-green herbal residues on the table and a biting smell of synthetic material were noted in his cell together with paraphernalia to smoke. In the right pocket of his shorts a capsule, with crunched small white fragments in it, was found the man was allegedly under medication with pregabalin and temazepam. The autopsy was performed the same day of the death.

Case 4

In February 2019, a 33-year-old male with past history of “Spice” consumption was found dead in his apartment. His partner reported that they had smoked together, approximately 3 g of ‘Spice’ at around 7.00 pm, and then they had gone to bed around 11.00 pm, feeling “stoned”. Resuscitation efforts, performed at 2.00 am the next morning, were not successful. The autopsy was performed with a PMI of 4 days.

Materials and methods

Reference materials and chemicals

The reference standard (5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE) and the internal standard (IS, JWH-200-d5) were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) and LGC standards GmbH (Wesel, Germany). Metabolites of the substance were not commercially available. Reference spectra of phase I metabolites generated by incubation of human liver microsomes and positive urine samples from persons with proven drug uptake were used as positive control samples for the detection of these analytes. All solvents were of analytical grade.

Methanol (HiPerSolv CHROMANORM®) and acetonitrile (HiPerSolv CHROMANORM®) were purchased from VWR Chemicals (Darmstadt, Germany). Ethyl acetate (p.a.) was obtained from Honeywell Riedel-de Häen® (Seelze, Germany). Sodium hydrogen carbonate (≥ 99.5%, anhydrous) and formic acid (p.a.) were from Carl Roth GmbH (Karlsruhe, Germany). Ammonium formate was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Sodium carbonate (≥ 99.5%, anhydrous) and n-hexane (LiChrosolv) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Deionized water was prepared using a Medica® Pro deionizer from ELGA (Celle, Germany). Mobile phase A (1% v/v ACN, 0.1% v/v HCOOH, 2 mM ammonium formate in water) and mobile phase B (0.1% v/v HCOOH, 2 mM ammonium formate in ACN) were freshly prepared prior to analysis.

Postmortem examination

A complete postmortem examination was performed on all corpses, including accurate external examination and internal section, as well as sampling of tissues for histopathological analysis. Samples of formalin-fixed tissues were analyzed for histology, after standard dying with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Samples of postmortem peripheral and central blood, urine, bile, hair, and brain tissue were also collected and submitted to toxicological analysis. In case 1, a postmortem chemical analysis of a sample of serum was also performed by the Clinical Laboratory of the Hospital. In case 4, a postmortem computerized tomography (PMCT) of the whole body took place, before the autopsy, at the Institute of Legal Medicine of Ulm. For each case, after toxicological analyses and a comprehensive revision of all data, a TSS was assigned, according to Elliott et. al. [9].

Toxicological general analyses

Systematic toxicological analyses were performed in each case, starting with a screening of urine and blood by means of immunoassay (Cloned Enzyme Donor Immunoassay (CEDIA), Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA, on a Konelab 30i for serum/blood, and Kinetic Interaction of Microparticles in Solution (KIMS) immunoassay, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany, on a Cobas c501 for urine) for the following substances: benzodiazepines, barbiturates, amphetamines, cannabinoids, cocaine, LSD, opiates and tricyclic antidepressants. Ethanol was determined by headspace gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) in femoral blood and urine applying validated and forensically accredited methods. The screening and quantification of classical drugs of abuse and “general unknown screenings” in femoral blood, central blood, stomach content and urine were performed by GC mass spectrometry (MS), high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection (HPLC–DAD) and/or liquid chromatography (LC)-MS using validated methods. In case 2, a bile sample was additionally analyzed. Validated methods were also applied to detect benzodiazepines and designer benzodiazepines, as well as opiates and synthetic opioids. Urine and hair samples were analyzed after updating previously published methods by inclusion of the recently emerged SCs [12,13,14].

5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE

A preliminary quantitative analysis of central and femoral blood for SCs was performed by means of an LC tandem MS (MS/MS) method validated for serum according to the literature guidelines [15], to orientate further analysis. Analytical parameters validated included selectivity, linearity, accuracy, precision, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), and matrix effects. To assess selectivity, six drug-free serum samples from five individuals, five of which without (blank samples) and one of which with the addition of IS (zero sample), were analyzed. Linearity was assessed using a seven-point calibration curve (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 ng/mL). Six calibration batches, all including a blank serum sample and a blank serum sample spiked with IS only (zero sample, final concentration of IS: 1 ng/mL), were analyzed on six different days. The seven-point calibration curve was plotted using the ratio of peak area of the analyte/peak area of IS versus the analyte concentration. Grubbs test, Cochran test and F-test, as well as selection of the best fitting calibration model, were performed using Valistat 2.0 software (Arvecon GmbH, Walldorf, Germany), in accordance with the guidelines of the German Society of Toxicological and Forensic Chemistry (GTFCh) [16].

For the assessment of accuracy and precision, quality control samples of pooled serum spiked at concentrations of 0.025 ng/mL (QC low) and 1.25 ng/mL (QC high) were analyzed in two replicates for each concentration per day (intra-day precision) and on six consecutive days (inter-day precision). Accuracy and precision were obtained by bias calculation and relative errors.

LOD and LOQ were determined by analyzing a nine-point calibration curve spiked in drug-free serum (0.001, 0.002, 0.003, 0.004, 0.005, 0.006, 0.007, 0.008, 0.01 ng/mL).

Matrix effects were assessed at two different concentrations (0.025 ng/mL and 1.25 ng/mL) by comparison of neat solutions of the analyte in the mobile phase A/B (80:20, v/v), pre-extraction and post-extraction spiked samples according to the protocol suggested by Matuszewski et al. [17].

The final quantification of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE in postmortem samples of cases 1–4 was performed via a standard addition method, which is often used for postmortem samples due to the expected matrix effects. The standard addition is a quantitative method designed to overcome the analytical difficulties which might arise from analyzing a complex sample, as in the case of postmortem blood. The quantitative analysis of the analyte of interest (in this case, 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE) is obtained by analyzing different samples: a first one only contains the matrix (e.g. blood) with an unknown amount of analyte, which is intended to be measured; other samples are obtained by adding different, exactly known amounts of the analyte to a fixed amount of the same sample material. A linear regression of the function (analyte peak area/IS peak area plotted against the added concentration) then allows for the extrapolation of the analyte concentration in the sample. This method allows to inherently take into account the recovery and avoids bias caused by matrix effects (e.g. ion suppression regarding the analyte or the IS), though it has the great disadvantage of the need for a high quantity of sample material. The accuracy of this method, which does not need a validation, is directly related to the linearity of the achieved curve.

Sample preparation, extraction procedure, and LC–MS/MS conditions

A liquid–liquid extraction was followed by LC–MS/MS analysis. Briefly, ‘extraction mixture I’ and ‘extraction mixture II’ were prepared with 990 mL of n-hexane and 10 mL of ethyl acetate (99:1 v/v) and with 800 mL of n-hexane and 200 mL of ethyl acetate (80:20 V/V), respectively. Secondly, 0.5 mL of carbonate buffer and 1.5 mL of the extraction mixture I were added to 250 µL of heart blood and 0.5 g of brain tissue. Subsequent to gentle overhead mixing for 5 min, the samples were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 20 min (Heraeus Megafuge 1.0, Thermo Scientific, Schwerte, Germany). Following this, 1 mL of the organic supernatant was transferred to an HPLC vial and evaporated to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen at 40 °C; 1.5 mL of extraction mixture II was added to the sample for a second extraction, which was performed in the same way (overhead mixing and centrifugation of the sample, transfer of the supernatant to the dried extract and evaporation to dryness). After complete evaporation, the sample was reconstituted in 100 μL of mobile phase A/B (80:20, v/v).

For postmortem femoral blood, samples of 100 µL were processed accordingly, reducing to half the volumes of carbonate buffer, extraction mixtures I and II, and organic supernatant transferred to vial. LC–MS/MS conditions were as stated in a previous publication [10]. Briefly, LC–MS/MS analysis was performed with an Ultimate 3000RS UHPLC (Dionex, Sunnyvale, USA) coupled to a QTRAP® 6500 triple quadrupole-linear ion trap instrument (SCIEX, Darmstadt, Germany) with positive electrospray ionization (ESI). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Kinetex® C18 column (2.6 μm, 100 Å, 100 × 2.1 mm; Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany). Total LC run time was 15 min, with mobile phase B starting at a concentration of 30%, linearly increased to 45% in 9.0 min, further increased to 70% in 1.0 min, further increased to 95% in 1.0 min, held for 2 min, and then decreased to starting conditions in 0.1 min and held for re-equilibration for 1.9 min. The autosampler was cooled down to 10 °C. Column oven temperature was 40 °C. Injection volume was 10 µL. The mass spectrometer was operated with positive electrospray ionization in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

Standard addition method and data interpretation

For quantitative blood analysis, methanolic solutions of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE were prepared at 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 ng/mL. Several glasses were prepared, each containing a fixed amounts of homogenized material (central/femoral blood), spiked with the abovementioned solutions of the target compound (5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE) to reach added concentrations of 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 1 ng/mL (used as points of the calibration curve) and with a fixed amount of IS. The number of points of the calibration curve depended on the available quantity of sample material, so that at least a 5-point calibration curve was realized for central blood. Given the generally lower amount of available femoral blood, at least four calibration points were deemed appropriate for femoral blood. Both calibration curves included a sample with addition of IS only.

For central blood, each sample (250 µL of blood) was spiked with 5 µL of IS and with 5 µL of the prepared 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE solutions (1–25 ng/mL). For femoral blood analysis, 100 µL sample material was spiked with 1 µL of IS and with the 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE solutions to obtain at least four of the aforementioned calibration points (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 1 ng/mL).

For brain samples, a 6-point calibration curve, blank sample fortified with IS included, was performed. Briefly, brain was minced with clean surgical scissors and homogenized. An amount of 0.5 g of tissue specimen was placed in a 1.5 mL plastic tube with a cap containing 1 mL of ACN, 10 µL IS (to reach a final concentration of 1 ng/mL). Except for a blank sample, 10 µL of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE solutions were added (prepared at 250, 500, 750, 1000 ng/mL dissolved in methanol). Five stainless beads were added to the mixture, the tube was capped, inserted into a bead beater-type homogenizer (Beads Crusher lT-12; TAITEC, Tokyo, Japan), vigorously shaken at 3200 rpm for 30 s and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm. Samples were shaken and centrifuged twice. One mL of the material was transferred to a large test tube for liquid–liquid extraction.

Concentrations of the target compound were calculated as x-axis intercept, plotting the spiked concentrations (x-axis) against the peak area ratio of analyte/IS (y-axis). To do such analysis, a linear regression was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.00 for Mac, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA).

Results

The standard addition method for the quantification of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE was applied to postmortem samples of cases 1–4 showing a good linearity for all specimens (mean R2 = 0.99). Calculated x-intercepts, range of the calibration curve, equations, goodness of fit and number of data points are given in Table 1.

Full results of the toxicological analyses for femoral blood, heart blood, urine and hair, including general screening and quantification of other drugs for cases 1–4 are shown in Table 2.

As for the validation of the LC–MS/MS method in serum, no interferences occurred in the selectivity tests. Good linearity was shown in serum for the concentration range of 0.01–2.0 ng/mL and a linear calibration model was accepted, with no need for a weighting factor (correlation coefficients (R2) = 0.997).

Data on LOD, LOQ, accuracy, precision, and matrix effects for the LC–MS/MS method (validated for serum only) used for preliminary analysis are provided in Table 3.

Case 1

Multiple patches of pink discoloration were noted over the large joints, as well as hematomas, scratches, and intracutaneous bleedings. Brain and lungs were edematous (1270 g and 1700 g, respectively). The trachea and the main bronchi contained brownish material aspirated from the stomach, which showed, at the esophageal and duodenal junctions, several hemorrhagic-erosive spots. In the small intestine, a brownish-blackish content, similar to coffee grounds, was seen. A pale discoloration of the endomyocardium was noted in the heart. The kidneys, both weighing 165 g, displayed bilateral cortical bleedings. Histology confirmed gross findings and showed a massive subacute stasis in the liver and subcapsular hemorrhages as well as acute tubular necrosis in kidneys.

Clinical chemical analysis showed high serum values of urea (391 mg/dL, reference range: 16.6–48.4 mg/dL), creatinine (17.4 mg/dL, reference range 0.67–1.17 mg/dL), and uric acid (12.1 mg/dL, reference range 3.4–7 mg/dL).

General screenings for common drugs, including further new psychoactive substances, were negative. Concentrations of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE and therapeutic drugs are shown in Table 2. Moreover, 0.03 ng/g of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE was measured in brain tissue.

Case 2

The victim showed abundant hypostasis associated to subcutaneous bleeding (i.e. “vibices”). On hair, face, in nostrils and mouth, stains of vomit were seen. The dentition displayed a poor hygiene and care condition. Signs of previous injection marks were found in the extremities and a fresh injection mark was seen over the right lateral malleolus.

Brain (1270 g) and pulmonary severe edema, with signs of acute stasis (left and right lung of a weight of 703 g and 602 g, respectively) was noted. There was no aspiration of gastric content, which consisted of about 200 mL of yellow-brownish material, without any peculiar smell or apparent tablet residues. The heart (334 g) and the cardio-circulatory system presented no abnormalities, apart from initial atherosclerosis. Liver and kidneys showed signs of acute blood stasis, in the context of severe hemolysis. The bladder contained 150 mL of clear urine.

Central blood, urine, and stomach content all tested positive for opiates by means of immunoassay, which additionally resulted positive for benzodiazepines and cannabinoids. As shown in Table 2, the HPLC/GC–MS analysis for classical drugs of abuse and medications further confirmed these results. Additionally, 1590 ng/mL of morphine was found in bile.

Case 3

The victim, 102 kg in weight and 174 cm in length, was overweight. Injection and paddle marks, as well as a tracheal tube, were consistent with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Bilateral conjunctival petechiae were seen, while no signs of defense injuries were noted. The status of the internal organs was mostly unremarkable, except for hepatosplenomegaly and for a severe visceral congestion, as frequently occurs in cases of blood stasis. Ribs from the third to the fifth were broken and this was considered a consequence of CPR. The main vessels of the body and the coronaries were affected by atherosclerosis, but no acute or severe occlusion could be found. Liver was fatty and fibrotic.

The toxicological analyses revealed 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE in central and femoral blood, as well as a number of therapeutic drugs (Table 2). The GC–MS analysis of the vegetal residues seized during the DSI allowed the identification of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE on the basis of the previously published GC–MS and LC-ESI-QtoF-MS mass spectra.

Case 4

Postmortem CT showed inhomogeneous material in the thorax, with an obstruction and deviation of the lumen of the main airways. This finding was confirmed by the autopsy, which showed signs of vomit and abundant gastric aspiration in the airways. Content of partially digested food was seen in the stomach (approx. 800 g). Due to partial digestion, an interval of approx. 2 h from the last meal to vomiting was assumed. Signs of asphyxia such as multiple petechiae in the eyes and over-inflation and edema (1620 g) of the lungs were noted. Brain edema (1470 g), massive blood stasis, especially of the right heart chambers and of the right part of the circulatory system, and hemolysis were also seen. Other organs were unremarkable, except for hepatomegaly. Toxicological analyses are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE has only recently emerged on the German drug market, though it seems to have gained popularity and almost completely replaced Cumyl-PEGACLONE, the first γ-carbolinone-type cannabinoid that was introduced in the end of 2016. Indeed, it was detected as the only active ingredient in 12 out of 15 herbal products purchased on the Internet and analyzed in 2019 [7]. Despite its widespread consumption, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data are still limited. The compound can presumably cause typical adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, somnolence, dizziness, anxiety, panic attacks, psychosis, tachycardia, seizures, and comatose states [18, 19], similarly to other potent CB1 receptor agonists. Seizures and collapse were reported in a case of SGT-151 administration [20], while in a recent study by Kevin RC et al., 2019, it was found that SCs, including those bearing a cumyl-substituent, such as 1-pentyl-N-(2-phenylpropan-2-yl)-1H-indole-3-carboxamide (CUMYL-PICA) and 1-(5-fluoropentyl)-N-(2-phenylpropan-2-yl)-1H-indole-3-carboxamide (5F-CUMYL-PICA), undergo thermal degradation with release of potentially toxic substances [21].

Several death cases involving SCs, e.g. methyl 2-{[1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indazole-3-carbonyl]amino}-3,3-dimethylbutanoate (5F-ADB), N-[(1S)-1-(aminocarbonyl)-2-methylpropyl]-1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide (AB-CHMINACA) and [1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indol-3-yl](naphthalene-1-yl)methanone (AM-2201), have been reported in the literature, often assigning a causative or contributory role to the compound(s) [11, 22,23,24,25]. The wide range of postmortem concentrations, overlapping those of non-fatal intoxications, strongly limits the possibility of identifying so-called “toxic ranges” [25, 26]. Indeed, the interpretative weight assigned to SCs in cases of death can largely vary among different evaluators [27]. The lack of data regarding postmortem redistribution and toxic effects further represents a challenge when assessing the TSS [9] of SCs in death cases and highlights that concentrations should be interpreted with caution, in a multi-disciplinary evaluation including circumstantial data and morphological assessment [9, 25].

In the cases here presented, non-specific findings of intoxication, e.g. vomiting and/or gastric aspiration, pulmonary and brain edema, injection marks, hemolysis and blood stasis in the internal organs, as well as an accumulation of urine in the bladder, were seen. The unavailability of morphological findings that could serve as cause of death, in combination with a past history of illicit drug consumption, highlighted the need for toxicological analyses. In all deaths, the detection of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE in blood and the presence of its main metabolites in urine indicated a recent intake of the substance.

In case 1, the appearance of the inner myocardial layers and the aspiration of gastric content were considered as signs of an agonal phase. Skin erythema and acute gastric erosions (i.e. Wischnewski-sign) are well-known signs of hypothermia, the latter being present in 40–90% of hypothermia-related deaths [28, 29]. Notwithstanding these typical findings, a death due to hypothermia, which remains a diagnosis of exclusion, cannot be confirmed, since the victim, a well-nourished individual, was found partially dressed and indoor at his home. Moreover, neither any open window or door nor any abnormalities in the room temperature, which was not measured, were reported from the DSI. On the other hand, according to experimental evidence in rats, SCs can induce a decrease in body temperature [30] and this could be additionally hypothesized in the present case, although available clinical data of survived SC intoxications does not support this.

The main active metabolite of risperidone, 9-hydroxy-risperidone (9-OH-risperidone), also available as a drug in its own right (paliperidone), trimipramine and diphenhydramine, were each within their typical therapeutic ranges (2–20 ng/mL, 10–300 ng/mL, and 50–100 ng/mL) [31, 32]. Even if a prolonged agony time could lead to a limited reduction of the initial drug concentrations and despite the possibility of an additional decrease of the blood concentrations due to postmortem redistribution (e.g. [33].), a primary role of these drugs in the death is very unlikely. Several indazole and γ-carbolinone based SCs and their metabolites were detected in scalp hair. Due to longitudinal diffusion, delayed incorporation, thermal instability of the compounds, and several other factors, hair analyses neither allow to determine the time of SC consumption by segmental hair analysis nor to certainly discriminate active use from passive exposure, i.e. contamination of hair from the outside during smoking [34,35,36]. The relatively high hair concentrations, as well as the multiplicity of the detected SCs, confirmed a pattern of consumption characterized by a long-term history of SCs use and, thus, suggested a certain tolerance to their effects. This is of utter importance, especially when the blood concentrations, as the ones retrieved in the present case (0.07 ng/mL in central and 0.45 ng/mL in peripheral blood), are not as high as in other SC involving intoxication cases found in the literature [25, 37, 38]. Lower levels were detected in heart blood, despite gastric regurgitation, which can lead to an increase in cardiac concentrations in the case of oral intake. The central compartment is more prone to passive postmortem redistribution from highly concentrated organs (e.g. lungs, liver) than the peripheral one, which only relies on diffusion from adipose tissues and muscles [39, 40]. The discrepancy observed can be due to several factors, one of them being a relatively short time interval between last consumption of the drug and death. In another case presented by Vogt et al. [41] with circumstantial evidence of methyl 2-[[1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-1H-indole-3-carbonyl] amino]-3,3-dimethylbutanoate (MDMB-CHMICA) consumption shortly prior to death, similar findings were reported. This points toward the possibility of higher concentrations in peripheral blood being the consequence of incomplete primary distribution of the drug at the time of death with initially very high concentrations, which might have declined at different speed in the heart vessels and the peripheral vessels. In cases 2–4, similar concentrations in peripheral and central blood or even higher concentrations in heart blood were detected. This further suggests that the discrepancy between central and peripheral blood concentrations in case 1 is not due to a passive redistribution from surrounding tissues to peripheral blood.

Given the absence of other plausible or potential causes of death, the consumption of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE as the cause of death seemed likely (a TSS of 3 was assigned), even though the exact mechanism remained unclear.

Despite hypothermia can lead to hemorrhages in pancreas, soft tissues and in synovial membranes, kidney bleedings have never been described in connection to this condition, not even when cases of death due to low temperatures were studied by means of postmortem computed tomography [28, 42,43,44]. In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported several cases of acute kidney injury (AKI) associated with SCs and particularly with [1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indol-3-yl](2,2,3,3-tetramethylcyclopropyl)methanone (XLR-11), a fluorinated compound [45]. None of these cases led to the death of the victim despite requiring corticosteroids therapy and/or hemodialysis. Thus, an extensive histopathological analysis did not take place and only renal biopsies were performed, showing signs of acute tubular injury [45]. These findings were confirmed by histology in our case. Kidney bleedings have never been previously demonstrated in such contexts, even though the ultrasound appearance of the cases presented by the CDC, which displayed an increase in cortical echogenicity, is consistent with subcapsular hemorrhage. Moreover, in all the cases described by the CDC and by other authors, the victims suffered from nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which were the chief symptoms at presentation [45,46,47,48]. AKI was also described in combination with fatal hepatic failure after the intake of another fluoro-SC, quinolin-8-yl 1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indole-3-carboxylate (5F-PB-22) [38]. Indeed, it seems unlikely to relate the subacute death of victim 1 to AKI, though a harmful effect of the fluorinated compound on kidneys appears probable. Recently, a painless macro-hematuria with altered coagulation was described in association with SC use, though no anticoagulant poisoning panel was performed [47]. Additionally, there were reports about products containing SCs allegedly laced with potent anticoagulant coumarin derivatives like brodifacoum and difenacoum [48, 49]. In our case, to verify if the kidney bleedings could have been caused by such contaminants, the analysis of coumarin derivatives including super-warfarin-type drugs was performed, but was found negative.

Finally, as a mechanism of death, we suggest a cardiac toxicity of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE with induction of tachycardia/arrhythmia.

In case 2, the toxicological analyses retrieved morphine (297 ng/mL), 6-acetylmorphine (6-AM, 20 ng/mL), codeine (21 ng/mL), oxazepam (450 ng/mL), and 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE (0.21 and 0.23 ng/mL in central and femoral blood). Heroin and morphine are sedative-hypnotic drugs, which can lead to respiratory depression. Since heroin is quickly deacetylated to 6-AM after ingestion and further metabolized to morphine, the presence of 6-AM in the blood of the deceased and the morphine/codeine ratio > 1 confirmed the intake of illicit heroin and suggested that the death occurred at a time close to the drug consumption [50,51,52]. The relatively low concentrations of morphine in bile (1590 ng/mL), compared to those retrieved in the literature [53], support a non-regular abuse of heroin in victim 2 [54, 55]. This finding was not consistent with the circumstantial data and with the multiple signs of past drug abuse retrieved at the autopsy (i.e. scars and crusts in injection sites and poor condition of the dentition in a woman of only 48 years). Even in the presence of past illicit drug use, it cannot be excluded that the victim had experienced a drug-free period and, thus, presented a low tolerance to the harmful effects of heroin, the main active metabolite of which was found in a concentration well above the typical toxic threshold (100 ng/mL for morphine [32, 56]).

It is to be noted that no synthetic opioids (e.g. fentanyl derivatives) were detected, while the consumption of several SCs was noted.

Despite the measured concentrations of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE were relatively low compared to opiates, similar levels were found in the other cases and even lower levels were retrieved in femoral blood of cases 3 and 4. Thus, such concentrations cannot be neglected.

The detection of metabolites of methyl (2S)-2-{[1-(4-fluorobutyl)-1H-indazole-3-carbonyl]amino}-3,3-dimethylbutanoate (4F-MDMB-BINACA) and of a common metabolite of N-(1-amino-3-methyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide (AB-FUBINACA) and methyl (2S)-2-[[1-[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]indazole-3-carbonyl]amino]-3-methylbutanoate (FUB-AMB) in urine but not in blood proves that the consumption of these drugs occurred in a larger time distance from death and was not relevant. Finally, oxazepam is a short-to-intermediate-acting benzodiazepine also known as an oxidative metabolite of other benzodiazepines and displays anxiolytic and sedative effects. Benzodiazepines are relatively safe drugs and, in the present case, oxazepam and alprazolam were both within the typical therapeutic ranges, so that a significant role in the death seems unlikely.

In the light of the above-mentioned, the death was attributed to an acute heroin intoxication. However, 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE may be considered as an additional factor in the course of the intoxication. As heroin definitely was the decisive intoxicant, a toxicological significance score of 1 was assigned to 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE.

In case 3, non-toxic concentrations of temazepam (230 ng/mL), oxazepam (12 ng/mL, probably found as a metabolite of temazepam), and alprazolam (16 ng/mL) were detected [32]. Moreover, pregabalin (6000 ng/mL), an antiepileptic drug also used to treat anxiety disorders, was detected in both heart and femoral blood. Patients treated with 600 mg/day of pregabalin usually show plasma concentrations between 2000 and 8000 ng/mL [56], with upper levels reaching 14,000 ng/mL [57]. Postmortem blood concentrations probably being causative to death were reported to be higher than 25,000 ng/mL [58]. As the victim was allegedly under constant temazepam and pregabalin medication, toxicological analyses confirmed the circumstantial data.

Concerning 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE, concentrations in central and peripheral blood were 0.22 ng/mL and 0.12 ng/mL, respectively. In this case, the attribution of a significance score (TSS) of 2 (“Medium”) to 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE is mainly due to the absence of competing causes of death at the postmortem examination and to the possible contributory role of pregabalin and temazepam (despite determined within therapeutic concentrations), since these compounds might have lowered the threshold for a central nervous system depressant effect or have interacted with the SC.

A SC intake was strongly suggested by the DSI, which allowed the identification of a herbal blend later confirmed to contain 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE. The mechanism of death remained unclear.

In case 4, the cocaine metabolites benzoylecgonine and ecgonine methyl ester as well as 11-nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannnabinol (THC-COOH), an oxidative metabolite of THC, were detected in blood, in the absence of the parent compounds. Cocaine is a centrally stimulating drug potentially leading to cardiac arrhythmias, an increase in body temperature, cerebral seizures, and respiratory paralysis, that is rapidly degraded in blood (half-life of 0.5–1.5 h [59]) resulting in a reduction of postmortem levels [60]. Thus, toxicity can hardly be estimated from blood concentrations [61]. In the present case, the absence of parent compound and the relatively low concentrations of the ester hydrolysis products indicate that the last cocaine intake was either very low-dosed or occurred with a larger time distance to death. Moreover, case 4 did not fit to the typical picture of cocaine-related fatalities [62], since no signs of (sub) acute cardiac events, aortic dissection or ruptured aneurysm were seen. The trace finding of THC-COOH, which is not pharmacologically active, was regarded as irrelevant. The aspiration of gastric content in a healthy, young man contradicts the assumption of a sudden death and/or a drug-induced arrhythmia, and is most probably secondary to a loss of consciousness. The big amount of food in the stomach and in the chest could be due to a “food-craving” effect, which is commonly experienced in association with cannabis [63, 64], though the appetite stimulation was reported less intense with SCs [65]. Somnolence and lethargy are commonly reported in association with SCs [66] and there are no other findings which could explain the state of low consciousness experienced by victim 4.

Hair analysis revealed both 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE and Cumyl-PEGACLONE. It is known that the presence of SCs in hair samples can arise not only from active intake, but also from an external contamination [13]. However, considering the relatively high concentrations of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE and the co-occurrence of Cumyl-PEGACLONE, a history of SC consumption in this case is likely.

A prominent role of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE, the only psychoactive substance detected despite relatively low concentrations in peripheral blood (0.09 ng/mL), was considered likely (TSS = 3). The death was caused by asphyxia due to SC-induced vomiting and aspiration of partially digested gastric content.

As shown in the present case series, the effects of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE are consistent with vomiting, convulsions, loss of consciousness, and respiratory depression. The compound could additionally cause a decrease in body temperature and kidney injuries. The occurrence of four cases of death involving 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE in a relatively short period of time (October 2018–February 2019) is a matter of public health concern. The ‘relative safety’ of SCs bearing a γ-carbolinone core structure suggested in the context of the use of Cumyl-PEGACLONE [8] was not confirmed in our case series, possibly due to the 5-fluorination accounting for higher potency and potential higher toxicity, which are still to be precisely assessed.

Regarding postmortem redistribution, given the uncertainties regarding the pharmacokinetic profile of the substance, the time between 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE consumption and death, mechanisms of death, effects of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and type of transport of the corpses, it is only possible to draw hypotheses. In case 1, it could be hypothesized an incomplete distribution of the substance at the moment of death due to very recent intake. In case 2, despite a very long PMI of 7 days, no difference between peripheral and central blood level was seen. Central to peripheral ratio (< 1, > 1 or = 1) has been historically used to assess postmortem redistribution, which in this case would be ruled out [40, 67]. However, in cases 3 and 4, which were characterized by a shorter PMI, concentrations were higher in heart blood than in femoral blood. Particularly in case 4, the central to peripheral ratio was 3.8. According to circumstantial data, the male had smoked approximately 7 h before being found dead, thus the SC absorption and distribution phase was probably over. It can be hypothesized that an initial postmortem redistribution may occur from highly concentrated organs (e.g. liver, lungs) to the central compartment in the first days after death, with a substantial equilibration of peripheral and central concentrations after a longer time interval. However, in-depth studies and further case reports/series are necessary to achieve a better understanding of this phenomenon, which has been described as a ‘toxicological nightmare’ [68].

From our data follows that for SCs, or at least for 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE, it seems not prudent to rely on the results of toxicological analyses performed with methods validated for serum when analyzing post-mortem material. However, if the available quantity of sample material does not allow standard addition for quantitation, this might be the only option and concentrations should be taken only as rough approximations then (in our cases there was a factor of 2 to 5 between the measured concentrations).

In the case series here presented, postmortem blood concentrations overlapped despite different TSS classification. This is a further confirmation that despite deaths involving SCs have increasingly been reported, the assessment of the toxicological significance is challenging and cannot rely on the mere results of toxicological analyses.

Conclusions

5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE is an emerging and extremely potent SC, which raises serious public health concerns. Several issues concerning postmortem redistribution, toxic concentration ranges, and possible mechanisms of death remain unsolved and demand increased research efforts and further studies. Our results emphasize that toxicological results should be taken with caution when methods are applied to postmortem samples if they were validated for other matrices only and standard addition should be preferred.

In forensic toxicological postmortem case work, and especially when novel compounds are involved, a comprehensive analysis of circumstantial, clinical, and postmortem findings, as well as an in-depth toxicological analysis is indispensable for a valid interpretation.

References

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2019) European Drug Report 2019: trends and developments. Publications Office of the European Union, Lisbon. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2019 Accessed 14 Aug 2019

Auwärter V, Dresen S, Weinmann W, Müller M, Pütz M, Ferreirós N (2009) ‘Spice’ and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs? J Mass Spectrom 4:832–837. https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.1558

Uchiyama N, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Kawahara N, Haishima Y, Goda Y (2009) Identification of a cannabinoid analog as a new type of designer drug in a herbal product. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 57:439–441

Schoeder CT, Hess C, Madea B, Meiler J, Müller CE (2018) Pharmacological evaluation of new constituents of "Spice": synthetic cannabinoids based on indole, indazole, benzimidazole and carbazole scaffolds. Forensic Toxicol 36:385–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11419-018-0415-z

Angerer V, Mogler L, Steitz JP, Bisel P, Hess C, Schoeder CT, Müller CE, Huppertz LM, Westphal F, Schäper J, Auwärter V (2018) Structural characterization and pharmacological evaluation of the new synthetic cannabinoid CUMYL-PEGACLONE. Drug Test Anal 10:597–603. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2237

Mogler L, Wilde M, Huppertz LM, Weinfurtner G, Franz F, Auwärter V (2018) Phase I metabolism of the recently emerged synthetic cannabinoid CUMYL-PEGACLONE and detection in human urine samples. Drug Test Anal 10:886–891. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2352

Ernst L, Langer N, Bockelmann A, Salkhordeh E, Beuerle T (2018) Identification and quantification of synthetic cannabinoids in 'spice-like' herbal mixtures: update of the German situation in summer 2018. Forensic Sci Int 294:96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.11.001

Halter S, Angerer V, Röhrich J, Groth O, Roider G, Hermanns-Clausen M, Auwärter V (2018) Cumyl-PEGACLONE: a comparatively safe new synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist entering the NPS market? Drug Test Anal 11:347–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2545

Elliott S, Sedefov R, Evans-Brown M (2018) Assessing the toxicological significance of new psychoactive substances in fatalities. Drug Test Anal 10:120–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2225

Mogler L, Halter S, Wilde M, Franz F, Auwärter V (2019) Human phase I metabolism of the novel synthetic cannabinoid 5F-CUMYL-PEGACLONE. Forensic Toxicol 37:154–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11419-018-0447-4

Kusano M, Zaitsu K, Taki K, Hisatsune K, Nakajima J, Moriyasu T, Asano T, Hayashi Y, Tsuchihashi H, Ishii A (2018) Fatal intoxication by 5F-ADB and diphenidine: detection, quantification, and investigation of their main metabolic pathways in humans by LC/MS/MS and LC/Q-TOFMS. Drug Test Anal 10:284–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2215

Franz F, Angerer V, Jechle H, Pegoro M, Ertl H, Weinfurtner G, Janele D, Schlögl C, Friedl M, Gerl S, Mielke R, Zehnle R, Wagner M, Moosmann B, Auwärter V (2017) Immunoassay screening in urine for synthetic cannabinoids - an evaluation of the diagnostic efficiency. Clin Chem Lab Med 55:1375–1384. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2016-0831

Moosmann B, Valcheva T, Neukamm MA, Angerer V, Auwärter V (2015) Hair analysis of synthetic cannabinoids: does the handling of herbal mixtures affect the analyst's hair concentration? Forensic Toxicol 33:37–44

Franz F, Jechle H, Angerer V, Pegoro M, Auwärter V, Neukamm MA (2018) Synthetic cannabinoids in hair—pragmatic approach for method updates, compound prevalences and concentration ranges in authentic hair samples. Anal Chim Acta 1006:61–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2017.12.029

Peters FT, Drummer OH, Musshoff F (2007) Validation of new methods. Forensic Sci Int 165:216–224

German Society of Toxicological and Forensic Chemistry (GTFCh) (2009) Guidelines for quality assurance in forensic-toxicological analyses. https://www.gtfch.org/cms/images/stories/files/Appendix%20B%20GTFCh%2020090601.pdf. Accessed 23 Sept 2019

Matuszewski BK, Constanzer ML, Chavez-Eng CM (2003) Strategies for the assessment of matrix effect in quantitative bioanalytical methods based on HPLC-MS/MS. Anal Chem 75:3019–3030

Hermanns-Clausen M, Kithinji J, Spehl M, Angerer V, Franz F, Eyer F, Auwärter V (2016) Adverse effects after the use of JWH-210 - a case series from the EU Spice II plus project. Drug Test Anal 8:1030–1038. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.1936

Hermanns-Clausen M, Müller D, Kithinji J, Angerer V, Franz F, Eyer F, Neurath H, Liebetrau G, Auwärter V (2018) Acute side effects after consumption of the new synthetic cannabinoids AB-CHMINACA and MDMB-CHMICA. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 56:404–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2017.1393082

Aknouche F, Ameline A, Richeval C, Schapira AJ, Coulon A, Maruejouls C, Gaulier JM, Kintz P (2019) Testing for SGT-151 (CUMYL-PEGACLONE) and its metabolites in blood and urine after surreptitious administration. J Anal Toxicol. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkz011

Kevin RC, Kovach AL, Lefever TW, Gamage TF, Wiley JL, Mcgregor IS, Thomas BF (2919) Toxic by design? Formation of thermal degradants and cyanide from carboxamide-type synthetic cannabinoids CUMYL-PICA, 5F-CUMYL-PICA, AMB-FUBINACA, MDMB-FUBINACA, NNEI, and MN-18 during exposure to high temperatures. Forensic Toxicol 37:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s11419-018-0430-0.

Schaefer N, Peters B, Bregel D, Kneisel S, Auwärter V, Schmidt PH, Ewald AH (2013) A fatal case involving several synthetic cannabinoids. Toxichem Krimtech 80:248–251

Hasegawa K, Wurita A, Minakata K, Gonmori K, Nozawa H, Yamagishi I, Watanabe K, Suzuki O (2015) Postmortem distribution of AB-CHMINACA, 5-fluoro- AMB, and diphenidine in body fluids and solid tissues in a fatal poisoning case: usefulness of adipose tissue for detection of the drugs in unchanged forms. Forensic Toxicol 33:45–53

Ivanov ID, Stoykova S, Ivanova E, Vlahova A, Burdzhiev N, Pantcheva I, Atanasov VN (2019) A case of 5F-ADB/FUB-AMB abuse: drug-induced or drug-related death? Forensic Sci Int 297:372–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.02.005

Kraemer M, Boehmer A, Madea B, Maas A (2019) Death cases involving certain new psychoactive substances: a review of the literature. Forensic Sci Int 298:186–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.02.021

Angerer V, Franz F, Schwarze B, Moosmann B, Auwärter V (2016) Reply to 'Sudden cardiac death following use of the synthetic cannabinoid MDMB-CHMICA'. J Anal Toxicol 40:240–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkw004

Labay LM, Caruso JL, Gilson TP, Phipps RJ, Knight LD, Lemos NP, McIntyre IM, Stoppacher R, Tormos LM, Wiens AL, Williams E, Logan BK (2016) Synthetic cannabinoid drug use as a cause or contributory cause of death. Forensic Sci Int 260:31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.12.046

Turk EE (2010) Hypothermia. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 6:106–115

Saukko P, Knight B (2015) Knight’s forensic pathology. CRC Press, Abingdon

Schindler CW, Gramling BR, Justinova Z, Thorndike EB, Baumann MH (2017) Synthetic cannabinoids found in "spice" products alter body temperature and cardiovascular parameters in conscious male rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 179:387–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.029

Reis M, Aamo T, Ahlner J, Druid H (2007) Reference concentrations of antidepressants. A compilation of postmortem and therapeutic levels. J Anal Toxicol 31:254–264

Schulz M, Iwersen-Bergmann S, Andresen H, Schmoldt A (2012) Therapeutic and toxic blood concentrations of nearly 1,000 drugs and other xenobiotics. Crit Care 16:R136. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11441

Saar E, Beyer J, Gerostamoulos D, Drummer OH (2012) The time-dependant post-mortem redistribution of antipsychotic drugs. Forensic Sci Int 222:223–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.05.028

Salomone A, Luciano C, Di Corcia D, Gerace E, Vincenti M (2014) Hair analysis as a tool to evaluate the prevalence of synthetic cannabinoids in different populations of drug consumers. Drug Test Anal 6:126–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.1556

Saito T, Sasaki C, Namera A, Kurihara K, Inokuchi S (2015) Experimental study on external contamination of hair by synthetic cannabinoids and effect of hair treatment. Forensic Toxicol 33:155–158

Franz F, Angerer V, Hermanns-Clausen M, Auwärter V, Moosmann B (2016) Metabolites of synthetic cannabinoids in hair–proof of consumption or false friends for interpretation? Anal Bioanal Chem 408:3445–3452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-016-9422-2

Saito T, Namera A, Ohta S, Miyazaki A, Osawa M, Inokuchi S (2013) A fatal case of MAM-2201 poisoning. Forensic Toxicol 31:333–337

Behonick G, Shanks KG, Firchau DJ, Mathur G, Lynch CF, Nashelsky M, Jaskierny DJ, Meroueh C (2014) Four postmortem case reports with quantitative detection of the synthetic cannabinoid, 5F-PB-22. J Anal Toxicol 38:559–562

Pélissier-Alicot AL, Gaulier JM, Champsaur P, Marquet P (2003) Mechanisms underlying postmortem redistribution of drugs: a review. J Anal Toxicol 27:533–544

Kennedy M (2015) Interpreting postmortem drug analysis and redistribution in determining cause of death: a review. Pathol Lab Med Int 7:55–62

Vogt S, Angerer V, Klima M, Geisenberger D, Pircher R, Auwärter V (2016) Synthetic cannabinoids contribute to the cause of death: two case reports involving MDMB-CHMICA and AB-CHMINACA. Poster presentation TIAFT 2016. https://www.uniklinik-freiburg.de/fileadmin/mediapool/08_institute/rechtsmedizin/pdf/Poster_2016/Vogt_S_-_Tiaft_2016.pdf Accessed 14 Aug 2019

Hejna P, Zátopková L, Tsokos M (2012) The diagnostic value of synovial membrane hemorrhage and bloody discoloration of synovial fluid ("inner knee sign") in autopsy cases of fatal hypothermia. Int J Legal Med 126:415–419

Kawasumi Y, Onozuka N, Kakizaki A, Usui A, Hosokai Y, Sato M, Saito H, Ishibashi T, Hayashizaki Y, Funayama M (2013) Hypothermic death: possibility of diagnosis by post-mortem computed tomography. Eur J Radiol 82:361–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.11.017

Zátopková L, Hejna P, Palmiere C, Teresiński G, Janík M (2017) Hypothermia provokes hemorrhaging in various core muscle groups: how many of them could we have missed? Int J Legal Med 131:1423–1428

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Synthetic Cannabinoid Use - Multiple States. MMWR 62:93–110. https://www.cdc.gov/MMWR/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6206a1.htm?s_cid=mm6206a1_w Accessed 14 Aug 2019

Buser GL, Gerona RR, Horowitz BZ, Vian KP, Troxell ML, Hendrickson RG, Houghton DC, Rozansky D, Su SW, Leman RF (2014) Acute kidney injury associated with smoking synthetic cannabinoid. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 52:664–673. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2014.932365

Hasan O, Patel AA, Sieger JJ (2019) A new differential diagnosis: synthetic cannabinoid-associated gross hematuria. Case Rep Med. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6327819

Kelkar AH, Smith NA, Martial A, Moole H, Tarantino MD, Roberts JC (2018) An outbreak of synthetic cannabinoid-associated coagulopathy in Illinois. N Engl J Med 379:1216–1223. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1807652

Arepally GM, Ortel TL (2019) Bad weed: synthetic cannabinoid–associated coagulopathy. Blood 133:902–905. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-11-876839

Fugelstad A, Ahlner J, Brandt L, Ceder G, Eksborg S, Rajs J, Beck O (2003) Use of morphine and 6-monoacetylmorphine in blood for the evaluation of possible risk factors for sudden death in 192 heroin users. Addiction 98:463–470

Wyman J, Bultman S (2004) Postmortem distribution of heroin metabolites in femoral blood, liver, cerebrospinal fluid, and vitreous humor. J Anal Toxicol 28:260–263

Konstantinova SV, Normann PT, Arnestad M, Karinen R, Christophersen AS, Morland J (2012) Morphine to codeine concentration ratio in blood and urine as a marker of illict heroin use in forensic autopsy samples. Forensic Sci Int 217:216–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.11.007

Bévalot F, Cartiser N, Bottinelli C, Guitton J, Fanton L (2016) State of the art in bile analysis in forensic toxicology. Forensic Sci Int 259:133–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.10.034

Tassoni G, Cacaci C, Zampi M, Froldi R (2007) Bile analysis in heroin overdose. J Forensic Sci 52:1405–1407

Karch SB, Drummer OH (2016) Karch’s pathology of drug abuse. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Moffat AC (2011) Clarke's analysis of drugs and poisons. Pharmaceutical Press, London

Arroyo S, Anhut H, Kugler AR, Lee CM, Knapp LE, Garofalo EA, Messmer S; Pregabalin 1008–011 International Study Group (2004) Pregabalin add-on treatment: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study in adults with partial seizures. Epilepsia 45:20–27

Elliott SP, Burke T, Smith C (2017) Determining the toxicological significance of pregabalin in fatalities. J Forensic Sci 62:169–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13263

Cone EJ (1995) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cocaine. J Anal Toxicol 19:459–478

Moriya F, Hashimoto Y (1996) Postmortem stability of cocaine and cocaethylene in blood and tissues of humans and rabbits. J Forensic Sci 41:612–616

Jones AW, Holmgren A (2014) Concentrations of cocaine and benzoylecgonine in femoral blood from cocaine-related deaths compared with venous blood from impaired drivers. J Anal Toxicol 38:46–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkt094

Tardiff K, Gross E, Wu J, Stajic M, Millman R (1989) Analysis of cocaine-positive fatalities. J Forensic Sci 34:53–63

Cota D, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Vicennati V, Stalla GK, Pasquali R, Pagotto U (2003) Endogenous cannabinoid system as a modulator of food intake. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27:289–301

Kirkham TC (2009) Cannabinoids and appetite: food craving and food pleasure. Int Rev Psychiatry 21:163–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260902782810

Winstock AR, Barratt M (2013) Synthetic cannabis: a comparison of patterns of use and effect profile with natural cannabis in a large global sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 131:106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.011

Brewer TL, Collins M (2014) A review of clinical manifestations in adolescent and young adults after use of synthetic cannabinoids. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 19:119–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12057

Dalpe-Scott M, Degouffe M, Garbutt D, Drost M (1995) A comparison of drug concentrations in postmortem cardiac and peripheral blood in 320 cases. Can Soc Forensic Sci J 28:113–121

Pounder DJ, Jones GA (1990) Post-mortem drug redistribution—a toxicological nightmare. Forensic Sci Int 45:253–263

Funding

This study was funded by the ‘Prevention of and Fight against Crime’ program of the European Commission (JUST/2013/ISEC/DRUGS/AG/6421).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the national ethical standards (retrospective study) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

No informed consent was required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giorgetti, A., Mogler, L., Halter, S. et al. Four cases of death involving the novel synthetic cannabinoid 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE. Forensic Toxicol 38, 314–326 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11419-019-00514-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11419-019-00514-w