Abstract

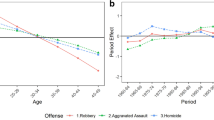

In this study, we use 1980–2019 longitudinal age-arrest data from Taiwan and applied the age-period-cohort-interaction (APC-I) model (Luo & Hodges, 2022) to examine the stability or change in the age-arrest distributions across five offenses. We focus on two research questions: (1) whether the shape of age-arrest curves in Taiwan diverges from the Hirschi and Gottfredson’s (HG) invariant premise after accounting for period and cohort effects; and (2) whether any observed period or cohort effects on age patterns vary depending on offense type. Findings indicate overall consistency in the shape of Taiwan’s age-arrest distributions after adjusting for period and cohort effects, which are characterized by relatively older peak ages and symmetrical spread-out distributions that diverge considerably from HG’s invariant projection and prototypical US age-arrest patterns. In addition, we find that period effects have contributed to higher arrest rates in recent years, and cohort effects have impacted somewhat the shape of Taiwan’s age-arrest distributions. These findings, along with recent cross-sectional evidence from Taiwan, South Korea, and India (Steffensmeier et al., 2017; 2019; 2020), further confirm that the aggregate age-crime relationship is robustly influenced by country-specific processes and historical and social transformations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

However, it is beyond the scope of the current study to examine specific mechanisms of period and cohort effects. We focus on testing if the age-crime patterns change when controlling for period and cohort effects.

Robustness check is conducted using the APC-mixed model (O’Brien et al., 2008) and the results support our main findings.

Since 2005, offenses of breach of trust, which was a subcategory of fraud, was classified as a separate category in the CIBP crime statistics. However, because breach of trust cases consitututed a minor portion of the overall fraud cases (less than 5% cases), the impact of this category change on our findings is small or negligible.

There are several important legal changes in drug laws in Taiwan. Notably, the enactment of the Narcotics Hazard Prevention Act in 1998 emphasized treating drug-addicted defendants as “diseased criminal” rather than just a “criminal”(Chen et al., 2021). Subsequent policy and legal revisions included the introduction of new medical treatment programs, new classifications of specific drugs, or changes in the punishment of specific types of drug offenders. These changes have been primarily driven by temporal changes in drug use patterns (e.g., HIV epidemic among people with injection drug use in the early 2000s). While these changes in law and policy may influence age-specific arrest patterns for drug law violations, the effect will be accounted for as either period or cohort effects in the APC analysis.

We do not show a discrete homicide category because this category in Taiwan includes not only lethal homicides (as characterizes the US homicide category), but also offenses such as kidnapping, assisting suicide, and attempted homicide/serious injury (e.g., assaults near to victim’s head or heart). Roughly 70% of homicide arrests in Taiwan are nonlethal based on its mortality statistics. Also, Hsing et al.’s study (2022) found that Taiwan has low a annual rate of lethal homicide (approximately 1/100,000) and the mean age of homicide victims is older than 35.

Details of the interpolation methods are included in Appendix 1. The linear interpolation method has been widely used in social sciences for estimating missing data and for estimating trends with inconsistent age or period intervals (Holly & Jones, 1997; Lidwall & Marklund, 2011; Rudnytskyi et al., 2015; Weden et al., 2015). In addition, we also conduct supplemental analysis with cubic spline interpolation methods(Bergstrom & Lam, 1989; McNeil et al., 1977). Results are presented in Appendix 1, Fig. 4. The overall patterns are similar to our main analysis.

The formula for calculating the PAI is the formula for calculating the PAI is: \({PAI}_{ij}= \frac{{r}_{ij}}{\sum {r}_{ij}}*100\),

where \({r}\) = age-specific arrest rate, \({i }\) = age category, and \(j\) = offense category. In the following analysis, PAI is used to plot the age-crime curves and calculate summary measures of the age-crime distribution (e.g., peak age, one-half peak descending, skewness).

All of the APC-I models are estimated using the sum-to-zero coding in R. Different from the conventional modeling approach that uses an age or period category as the reference group, the coefficients estimated using the sum-to-zero coding represent the deviation from the grand mean of all the observations. This approach also makes the interpretation of interaction terms easier as each coefficient of the interaction term represents the deviation from the expected values based on the main effects. Moreover, this approach also allows us to adjust for the arrest level differences across comparisons (e.g., offense types or vs HG invariance projection)—that is, we can compare the estimated coefficients across countries as the mean differences across countries are held constant in the model.

We aggregate the data into 5-year categories to avoid random yearly fluctuation and also to better measure the concept of cohort and potential cohort effects. As Easterlin (1987) has noted, a 1-year bulge in the population can be easily absorbed by different social institutions (i.e., labor market, schools), but a 5- or 10-year bulge cannot.

We also conducted a series of deviance tests to examine the unique contributions of age, period, and cohort effects in the APC-I model across the five offense types (Luo & Hodges, 2022). Results suggest that the full APC-I model provides significantly better fit to the data than the partial models. Therefore, we conclude that age, period, and cohort effects are significant factors in explaining the age-specific arrest rates across the five offense types in Taiwan. The deviance test results are presented in Appendix 2, Table 3.

There is a small dip observed in the average age distributions of theft, assault, and total which parallel the mandatory military service required for all young males in Taiwan. The dip is followed by an increase in arrests that lasts well into midlife ages.

Note also the age pattern for total arrests is heavily swayed by large volume of arrests for theft.

An additional research pursuit involves the ongoing monitoring of Taiwan age-arrest trends to document whether current age curves become more/less symmetrical in the years ahead as today’s youth and preteen cohorts transition through the life course. Of interest, particularly, is whether the current symmetrical distribution for theft persists in the decades ahead or becomes more adolescent spiked as was observed in the 1980s timeline.

References

Barnes, J., Jorgensen, C., Pacheco, D., & Eyck, M. (2014). The puzzling relationship between age and criminal behavior: A biosocial critique of the criminological status quo. In K. Beaver, J. Barnes, & B. Boutwell (Eds.), The nurture versus biosocial debate in criminology: On the origins of criminal behavior and criminality (pp. 397–413). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349114.n24

Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2014). Another ‘futile quest’? A simulation study of Yang and Land’s hierarchical age-period-cohort model. Demographic Research, 30, 333–360.

Bergstrom, T., & Lam, D. (1989). Recovering event histories by cubic spline interpolation. Mathematical Population Studies, 1(4), 327–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/08898488909525283

Bond, M. (2010). Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology. Oxford University Press.

Chen, Y.-H., & Yi, C.-C. (2005). Taiwan’s families. Sage.

Chen, W. J., Chen, C.-Y., Wu, S.-C., Wu, K.C.-C., Jou, S., Tung, Y.-C., & Lu, T.-P. (2021). The impact of Taiwan’s implementation of a nationwide harm reduction program in 2006 on the use of various illicit drugs: Trend analysis of first-time offenders from 2001 to 2017. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00566-5

Clinard, M. B., & Abbott, D. J. (1973). Crime in developing countries: A comparative perspective. Wiley.

Department of Household Registration. (2015). Taiwan statistics yearbook. Department of Household Registration. https://statdb.dgbas.gov.tw/pxweb/dialog/statfile9L.asp

Easterlin, R. A. (1987). Birth and fortune: The impact of numbers on personal welfare. University of Chicago Press.

Farrington, D. P. (1986). Age and crime. Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, 7, 189–250.

Fritsch, F. N., & Carlson, R. E. (1980). Monotone piecewise cubic interpolation. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis, 17(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1137/0717021

Greenberg, D. F. (1985). Age, crime, and social explanation. American Journal of Sociology, 91(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/228242

Greenberg, D. F. (2008). Age, sex, and racial distributions of crime. Out of control: Assessing the general theory of crime (pp. 38–48). Stanford University Press.

Greenberg, D. F., & Larkin, N. J. (1985). Age-cohort analysis of arrest rates. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 1(3), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01064634

Harada, Y. (1994). A longitudinal analysis of juvenile arrest histories of the 1970 birth cohort in Japan. In E. G. M. Weitekamp & H.-J. Kerner (Eds.), Cross-national longitudinal research on human development and criminal behavior, 76, 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0864-5_3

Ho, D. Y. F. (1989). Continuity and variation in Chinese patterns of socialization. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51(1), 149–163.

Holly, S., & Jones, N. (1997). House prices since the 1940s: Cointegration, demography and asymmetries. Economic Modelling, 14(4), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-9993(97)00009-6

Hsieh, M., & Shek, D. (2008). Personal and family correlates of resilience among adolescents living in single-parent households in Taiwan. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 49, 330–348.

Hsing, S.-C., Chen, C.-C., Huang, S.-H., Huang, Y.-C., Wang, B.-L., Chung, C.-H., Sun, C.-A., Chien, W.-C., & Wu, G.-J. (2022). Trends in homicide hospitalization and mortality in Taiwan, 1998–2015. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4341. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074341

Huang, L.-W.W. (2013). The transition tempo and life course orientation of young adults in Taiwan. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 646(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212464861

Ikels, C. (2004). Filial piety: Practice and discourse in contemporary East Asia. Standford University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American sociological review, 65(1), 19–51.

Jen, W., Chang, W., & Chou, S. (2006). Cybercrime in Taiwan – an analysis of suspect records. In H. Chen, F.-Y. Wang, C. C. Yang, D. Zeng, M. Chau, & K. Chang (Eds.), Intelligence and security informatics (pp. 38–48). Springer.

Kao, Y.-C., & Bih, H.-D. (2014). Masculinity in ambiguity: Constructing Taiwanese masculine identities between great powers. In J. Gelfer (Ed.), Masculinities in a global era (pp. 175–191). Springer.

Kostaki, A., & Panousis, V. (2001). Expanding an abridged life table. Demographic Research, 5, 1–22.

Lidwall, U., & Marklund, S. (2011). Trends in long-term sickness absence in Sweden 1992–2008: The role of economic conditions, legislation, demography, work environment and alcohol consumption. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20(2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00744.x

Liu, J., Zhang, L., & Messner, S. (2001). Crime and social control in a changing China. Greenwood Press.

Lu, Y., Luo, L., & Santos, M. R. (2022). Social change and race-specific homicide trajectories: An age-period-cohort analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224278221129886

Lu, Y., & Luo, L. (2021). Cohort variation in U.S. violent crime patterns from 1960 to 2014: An age–period–cohort-interaction approach. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 37, 1047–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-020-09477-3

Luo, L. (2013). Assessing validity and application scope of the intrinsic estimator approach to the age-period-cohort problem. Demography, 50(6), 1945–1967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0243-z

Luo, L., & Hodges, J. S. (2022). The age-period-cohort-interaction model for describing and investigating inter-cohort deviations and intra-cohort life-course dynamics. Sociological Methods & Research, 51(3), 1164–1210.

Mannheim, H. (1965). Comparative criminology: A textbook. Routledge.

McNeil, D. R., Trussell, T. J., & Turner, J. C. (1977). Spline interpolation of demographic data. Demography, 14(2), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060581

O’Brien, R. M. (1989). Relative cohort size and age-specific crime rates: An age-period-relative-cohort-size model. Criminology, 27(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1989.tb00863.x

O’Brien, R. M., & Stockard, J. (2009). Can cohort replacement explain changes in the relationship between age and homicide offending? Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-008-9059-1

O’Brien, R. M., Hudson, K., & Stockard, J. (2008). A mixed model estimation of age, period, and cohort effects. Sociological Methods & Research, 36(3), 402–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124106290392

Pelzer, B., te Grotenhuis, M., Eisinga, R., & Schmidt-Catran, A. W. (2015). The non-uniqueness property of the intrinsic estimator in APC models. Demography, 52(1), 315–327.

Pridemore, W. A. (2003). Demographic, temporal, and spatial patterns of homicide rates in Russia. European Sociological Review, 19(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/19.1.41

Raymo, J., Park, H., Xie, Y., & Yeung, W. J. (2015). Marriage and family in East Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 471–492.

Rudnytskyi, O., Levchuk, N., Wolowyna, O., Shevchuk, P., & Kovbasiuk (Savchuk), A. (2015). Demography of a man-made human catastrophe: The case of massive famine in Ukraine 1932–1933. Canadian Studies in Population [ARCHIVES], 42(1–2), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.25336/P6FC7G

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30(6), 843–861. https://doi.org/10.2307/2090964

Santos, M. R., Testa, A., Porter, L., & Lynch, J. (2019). The contribution of age structure to the international homicide decline. PLoS ONE, 14(10), 1–28.

Steffensmeier, D., & Allan, E. (2000). Looking for patterns: Gender, age, and crime. In J. Sheley (Ed.), Criminology: A contemporary handbook (pp. 85–128). Wadsworth.

Steffensmeier, D., Allan, E. A., Harer, M., & Streifel, C. (1989). Age and the distribution of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 94(4), 803–831.

Steffensmeier, D., Streifel, C., & Shihadeh, E. S. (1992). Cohort size and arrest rates over the life course: The easterlin hypothesis reconsidered. American Sociological Review, 57(3), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096237

Steffensmeier, D., Zhong, H., & Lu, Y. (2017). Age and its relation to crime in taiwan and the United States: Invariant, or does cultural context matter? Criminology, 55(2), 377–404.

Steffensmeier, D., Lu, Y., & Kumar, S. (2018). Age–crime relation in India: Similarity or divergence vs. Hirschi/gottfredson inverted j-shaped projection? The British Journal of Criminology, 59(1), 144–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azy011

Steffensmeier, D., Lu, Y., & Na, C. (2020). Age and crime in South Korea: Cross-national challenge to invariance thesis. Justice Quarterly, 37(3), 410–435.

Weden, M. M., Peterson, C. E., Miles, J. N., & Shih, R. A. (2015). Evaluating linearly interpolated intercensal estimates of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of U.S. counties and census tracts 2001–2009. Population Research and Policy Review, 34(4), 541–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-015-9359-8

Wei, H. S., & Chen, J. K. (2014). The relationships between family financial stress, mental health problems, child rearing practice, and school involvement among Taiwanese parents with school-aged children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(7), 1145–1154

Weisburd, D., Wilson, D. B., Wooditch, A., & Britt, C. (2022). Count-based regression models. In D. Weisburd, D. B. Wilson, A. Wooditch, & C. Britt (Eds.), Advanced Statistics in Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 233–271). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67738-1_6

Yang, C., Chen, K., & Li, T. (2006). Persistence and transition of family structure in contemporary Taiwan, 1984–2005. Taiwan social change 1985–2005: Marriage and family (pp. 2–28). Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica.

Zhang, L. (2008). Juvenile delinquency and justice in contemporary China: A critical review of the literature over 15 years. Crime, Law and Social Change, 50(3), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-008-9137-1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Yunmei Lu and Darrell Steffensmeier. Yunmei Lu conducted the data analysis and developed the first draft and Darrell Steffensmeier edited and commented on various versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Interpolation and Robustness Check

The linear interpolation method has been widely used in social sciences for estimating missing data and for estimating trends with inconsistent age or period intervals (Holly & Jones, 1997; Lidwall & Marklund, 2011; Rudnytskyi et al., 2015; Weden et al., 2015). It assumes linear changes between two known data points; thus, it uses linear polynomials to construct new data points between each two known observations. For instance, for data before 2008, we first disaggregate the 10-year age groups of age 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59 using the linear interpolation function in R (“approx” function) and then rearrange the age group to 5-year increments. The same approach is for the 10-year age groups of age 40–49 and 50–59 in the data after 2008.

We opt for linear interpolation in the main analysis for its parsimony, but we also conduct a supplemental analysis with the cubic spline interpolation technique to ensure our results are consistent across different interpolation methods (McNeil et al., 1977). Cubic-spline interpolation is a special case for spline interpolation where a set of piecewise cubic functions are used to interpolate and smooth a set of data points. It is also a commonly used interpolation method in social science research (Bergstrom & Lam, 1989; Fritsch & Carlson, 1980; Kostaki & Panousis, 2001; McNeil et al., 1977). Appendix Fig. 4 replicates Fig. 1 in the main analysis and demonstrates the histogram of the age-crime distribution of four different periods in Taiwan based on cubic-spline interpolation techniques (“spline” function in R with “natural” method). The interpolated results for single-year estimates vary slightly from the same estimates based on the linear-interpolation results, but once we re-arrange the data into 5-year age categories to reduce instability, the interpolated patterns are almost identical across the two interpolation techniques. The patterns depicted in Appendix Fig. 4 (based on cubic spline interpolation) mirror those observed in are the same as the patterns observed in Fig. 1 (based on linear interpolation). Replication of the age-period-cohort analyses also demonstrates consistent findings.

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

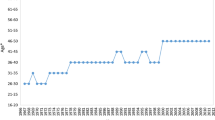

Estimated period main effects on different offenses in Taiwan. Notes: The horizontal solid line represents zero deviation from the global mean (intercept of the APC-I model). Points above the zero line represent positive deviations from the global mean, suggesting higher-than-expected risks of arrest; points below the zero line represent negative deviations from the global mean, suggesting lower-than-expected risks of arrest

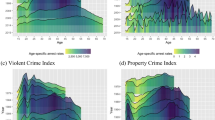

Estimated inter-cohort deviations of different offenses in Taiwan. Notes: The horizontal solid line in each plot represents no deviation from the predicted arrest rate determined by age and period main effects. Points that fall on the zero line represent no cohort effects (i.e., age and period main effects are sufficient to determine the arrest rate). Points above the line indicate cohorts with higher arrest rates than the predicted values determined by age and period main effects. Points below the zero line indicate cohorts with lower arrest rates than the predicted values determined by age and period main effects

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Steffensmeier, D. Stability or Change in Age-Crime Relation in Taiwan, 1980–2019: Age-Period-Cohort Assessment. Asian J Criminol 18, 433–458 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-023-09412-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-023-09412-y