Abstract

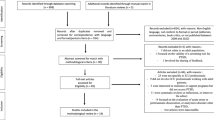

The capacity of electronic health records (EHRs) to capture desired information depends on the practices of health care providers. These practices have not been well studied in relation to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This qualitative study investigated how providers write EHR notes on PTSD through 38 interviews with providers working at five Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals across the United States of America. Two overarching themes were prominent in the results. Providers used progress notes primarily to remember and access details for direct patient care, but only rarely for care coordination. Providers infrequently recorded information not judged to directly contribute to improved care, sometimes deliberately omitting information perceived to jeopardize patients’ access to, or quality of, care. Omitted information frequently included sexual or non-military trauma. Understanding providers’ thought processes can help clinicians be aware of the limitations of EHR notes as a tool for learning the histories of new patients. Similarly, researchers relying on EHR data for PTSD research should be aware of likely areas of missing data.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Institute of Medicine. Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Military and Veteran Populations: Initial Assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academics Press. 2012.

Rosen C, Adler E, Tiet Q. Presenting concerns of veterans entering treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2013; 26: 640–643.

Zhou YY, Garrido T, Chin HL, et al. Patient access to an electronic health record with secure messaging: impact on primary care utilization. American Journal of Managed Care. 2007; 13 (7): 418–424.

Earnest MA, Ross SE, Wittevrongel L, et al. Use of a patient-accessible electronic medical record in a practice for congestive heart failure: patient and physician experiences. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2004: 11(5):410–417.

Häyrinen K, Saranto K, Nykänen P. Definition, structure, content, use and impacts of electronic health records: a review of the research literature. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2008; 77: 291–304.

Cloitre M, Courtois CA, Charuvastra A, et al. Treatment of complex PTSD: results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2011; 24 (6): 615–627.

Vojvoda D, Stefanovics E, Rosenheck RA. Treatment of veterans with PTSD at a VA medical center: primary care versus mental health specialty care. Psychiatric Services 2014; 65: 1239–1243.

McCarron KK, Reinhard MJ, Bloeser KJ, Mahan, CM, Kang HK. PTSD Diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans: comparison of administrative data to chart review. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2014: 27: 626–629.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL . Doing Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications, 1992

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 2005; 15(9):1277–88.

Veterans Health Administration. Programs for Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration, 2010.

Cloitre M, Petkova E, Wang J, et al. An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depression and Anxiety 2012; 29:709–717.

Surís A, Link-Malcolm J, Chard K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of cognitive processing therapy for veterans with PTSD related to Military Sexual Trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2013; 26: 28–37.

Resick PA, Williams LF, Suvak MK, et al. Long-term outcomes of cognitive-behavioral treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder among female rape survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2012; 80 (2): 201–210.

Jayawickreme N, Cahill SP, Riggs Ds, et al. Primum non nocere (first do no harm): symptom worsening and improvement in female assault victims after prolonged exposure for PTSD. Depression and Anxiety 2014; 31: 412–419.

Hoyt T, Klosterman Rielage J, Williams LF. Military Sexual Trauma in men: exploring treatment principles. Traumatology 2012; 18: 29–40.

Ponniah K, Hollon SD. Empirically supported psychological treatments for adult acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. Depression and Anxiety 2009; 26: 1086–1109.

Resick PA, Suvak MK, Wells SY. The impact of childhood abuse among women with assault-related PTSD receiving short-term cognitive-behavorial therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2014; 27: 558–567.

Millard WB. Electronic health records: Promises and realities (part III). Annals of Emergency Medicine 2010; 56:4 19A–25A.

Reich A. Disciplined doctors: the electronic medical record and physicians’ changing relationship to medical knowledge. Social Science and Medicine 2012; 74: 1021–1028.

Bodenheimer T, Yoshio Lang B. The teamlet model of primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 2007; 5:457–61.

Williams JW, Jackson G, Powers B, et al. The patient centered medical home closing the quality gap: revisiting the state of the science. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012.

Delbanco T, Walker J, Bell SK.,et al. Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: a quasi-experimental study and a look ahead. Annals of Internal Medicine 2012; 157(7):461–470.

Woods SS, Schwartz E, Tuepker A, et al. Patient experiences with full electronic access to health records and clinical notes through the MyHealtheVet Personal Health Record Pilot: qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2013; 15(3):e65.

Perera G, Holbrooke A., Thabanea L, et al. Views on health information sharing and privacy from primary care practices using electronic medical records. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2011; 80: 94–101.

Tai B, McLellan AT. Integrating information on substance use disorders into electronic health record systems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2012; 43: 12–19.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the VA’s Health Services Research and Development Service through its Consortium for Health Informatics Research (CHIR). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors would like to thank all members of the Consortium for Health Informatics Research (CHIR) PTSD research team, with particular thanks to Jessica Robb for project coordination.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, related to the content of this paper. Funding for this research was provided by the VA’s Health Services Research and Development Service through its Consortium for Health Informatics Research (CHIR). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Guide to Provider Interviews

Open-ended cognitive prompt

First can you tell me in your own words your thoughts on how you constructed the record? Just walk me through what you did first, second, third (etc.) and why you did it this way.

Data location

-

1)

So when you started writing the note, what was the note title that you used?

-

2)

To set some context, please tell me briefly how long you’ve been seeing this patient, and approximately how frequently.

-

3)

Why was the patient in clinic on this occasion?

-

4)

Did you have to choose which note title to use? If yes: was choosing the note title easy or difficult, in this case? Why?

-

5)

Did you create entries under any other note titles associated with this visit? What were they?

Template use

-

6)

Did you use a template to create this note? If yes - Is it a template you created, or did someone else create it?

Identifying continuity and change

-

7)

Were there some parts of this note that you created before your visit with the patient? If yes and probe is necessary: can you point out those sections, please.

-

8)

What information do you always record for a patient, every visit?

-

9)

Did you look back to previous notes on this patient to borrow any language that you used here?

-

10)

Did you look at other notes for other reasons?

-

11)

How far back did you look?

-

12)

Could you always find what you were looking for? If not, what made finding the information difficult?

-

13)

What information recorded here indicates a change since you last saw the patient?

Ability of notes to capture important information

-

14)

What clinical information was most important to you to record in this note?

-

15)

Is there anything interesting about this visit that you remember that you didn’t include in the note?

-

16)

Was there anything that was important but that you felt there was a good reason not to include? If yes, and prompt is necessary: why was that information not recorded? Was there not a place to record it or is there a reason you decided not record that information?

-

17)

Is there anything you wrote in the note that you intended to really stand out and be noticeable, either to yourself or to others reading the note? If yes, and prompt is necessary: how did that desire to make this information noticeable influence the wording you used?

-

18)

Other than documenting that the visit occurred, does this note serve a particular purpose for you? If yes and prompt is necessary: what was that purpose, and how did that influence what you wrote?

Use of vague language/omissions

-

19)

Is there anything in this note that you wrote in such a way that it is intended to remind you of some detail, without actually putting it in writing?

-

20)

Was your wording in this note affected in any way by the people you expect to read the note - for example, other providers, or Department of Defense personnel, or the patient? If yes and probe is necessary: can you describe how this influenced your word choices?

Key word use/location

-

21)

What are the key terms, if any, that you would always be sure to include in your notes in describing a patient like this one?

-

22)

Did you consider using the term “resiliency” in writing this note? Are there other terms you use that you feel mean the same thing?

-

23)

Did you consider using the term “recovery” in writing this note? Are there other terms you use that you feel mean the same thing?

-

24)

Can you describe how you decided on the language you used here to talk about suicide risk or suicidality?

-

25)

Can you describe how you decided on the language you used here to talk about any substance use?

-

26)

Do you find it useful to record information about the patient’s living conditions or social interactions? If yes: where do you record that kind of information?

-

27)

Do you record information about patient-reported interactions with the legal or criminal justice system?

Recording of quotes/patient vs. provider words

-

28)

If you include information in the note at a patient’s request, do you indicate that request in some way?

-

29)

If a patient makes a statement that you feel should be recorded, but it is in conflict with your assessment – for example, the patient says “I’m really feeling so much better,” but appears to have poorer functioning – do you usually indicate that conflict?

Provider Communication

Did you write anything in this note with the direct purpose of communicating with another specific provider?

Time use

Finally, about how long did you spend writing this note the first time, do you think? What took the most time?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tuepker, A., Zickmund, S.L., Nicolajski, C.E. et al. Providers’ Note-Writing Practices for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder at Five United States Veterans Affairs Facilities. J Behav Health Serv Res 43, 428–442 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-015-9472-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-015-9472-9