Abstract

The acquisition of online interaction competencies is an important learning objective. The present study explored the relationships between the first-language heterogeneity of computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) groups and the development of students’ online interaction self-efficacy via a pretest–posttest design in the context of a nine-week CSCL course. The research participants were 1525 freshmen receiving distance education who were randomly assigned to 343 CSCL groups. Independent of their own language status, students in CSCL groups featuring first-language heterogeneity exhibited lower precourse–postcourse gains in online interaction self-efficacy than students in groups without heterogeneity. Consistent with a theoretically derived moderation model, the relationships between first-language heterogeneity and self-efficacy gains were moderated by the amount of time that the groups spent on task-related communication during the initial collaboration phase (i.e., the relationships were significant when little time was spent on it but not when a great deal of time was spent on it). In contrast, the amount of time that groups spent on communication related to getting to know each other was ineffective as a significant moderator. Follow-up analyses indicated that time spent getting to know each other in first-language heterogeneous CSCL groups seems to have had the paradoxical effect of increasing rather than decreasing perceptions of heterogeneity among group members. Apparently, this effect impaired online interaction self-efficacy gains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An increasing body of research documents the role of students’ online interaction self-efficacy—the expectation that one will be able to communicate and interact effectively with other students—in computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) (e.g., Isohätälä et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2013; Sinha et al., 2015). The acquisition of online interaction competencies is an important learning objective. In the present research, we explored the relationships between the first-language heterogeneity of computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) groups and the development of students’ online interaction self-efficacy via a pretest–posttest design in the context of a nine-week CSCL course. We examined the role played by first-language heterogeneity for the following reasons. First, people develop their self-efficacy expectations on the basis of personal experiences (see Bandura, 1997, for a more general discussion of self-efficacy development). Second, the proportion of second-language speakers in educational institutions has steadily increased over recent decades (e.g., Kukulska-Hulme & Pegrum, 2018; Morrice et al., 2017). Third, research in different fields shows that first-language heterogeneity in learning contexts is often accompanied by specific challenges that can affect the quality of students’ interaction experiences (e.g., Van Wyk & Haffejee, 2017). The investigation of the relationships between first-language heterogeneity and online interaction self-efficacy is thus of both theoretical and practical relevance.

Theoretical background

The role of first-language heterogeneity in CSCL

Statistics show that linguistic heterogeneity among students is rising: The OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), for instance, notes that the proportion of students with an immigrant background increased by approximately 3% between 2006 and 2015, from 9.4% to 12.5% (OECD, 2016). Likewise, the U.S. Census Bureau reports that the number of immigrant students increased from 20% to 28% of all students enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities between 2000 and 2018 (Batalova & Feldblum, 2020). To date, however, comparatively few studies have examined the effects of first-language heterogeneity in CSCL groups (i.e., the distribution of differences among students in terms of whether their first language is used as the language of instruction). In fact, a computer-based literature review search of texts published through December 2022 in major psychological and educational databases provided by EBSCOhost (e.g., PsycArticles, PsycInfo, Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection, ERIC, Education Source), which included “language”, “heterogeneity”, “computer supported”, “computer mediated” or “CSCL” as search terms, yielded no articles examining the relationships between CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity and online interaction competence acquisition. However, some studies highlight the negative effects of first-language heterogeneity on other CSCL outcomes. For example, Usher and Barak (2020) report that heterogeneity in terms of individuals’ “mother tongues” was a positive predictor of innovation for face-to-face student groups but a negative predictor for online groups. Likewise, studies concerning CSCL in multinational or transcultural settings report lower learning outcomes among culturally heterogeneous CSCL groups than culturally homogeneous CSCL groups (e.g., Popov et al., 2013; Stepanyan et al., 2014).

At present, there is no unified theoretical framework for studying the effects of first-language heterogeneity on CSCL. Nevertheless, several pieces of evidence suggest that, unless it is explicitly managed, first-language heterogeneity may increase the likelihood of dissatisfactory interactions among students. First, in many scenarios, CSCL relies on written language, especially in contexts featuring asynchronous collaboration (e.g., written messages, collaborative writing on shared documents; see, e.g., Cress et al., 2021). Thus, different levels of linguistic competencies on the part of students within the collaboration can create objective barriers to task-related communication, such as textual misinterpretations or the loss of paralinguistic nuances that are present in verbal communication, thereby complicating task-related coordination and collaboration among students (e.g., Berg, 2012). Second, from a social psychological perspective, first-language heterogeneity may also create additional barriers. Social psychological models such as the social identification model of deindividuation effects (SIDE; Lea & Spears, 1991; Spears, 2017) claim, for instance, that the relative lack of individualizing cues associated with computer-mediated communication increases the influence of easily available surface-level social categorical information in students’ interactions (e.g., Flanagin et al., 2002; Spears et al., 2002). Linguistic features are generally strong markers of ethnic and cultural category membership (e.g., Giles & Ogay, 2007). Linguistic features may therefore trigger a variety of stereotypes among CSCL students that can influence communication and collaboration activities in CSCL groups in multiple ways (e.g., paternalistic communication patterns, feelings of stereotype threat, intergroup biases and anxieties). The present research did not intend to differentiate between task-related and stereotype-based processes as contributors to first-language heterogeneity effects. Rather, it aimed to investigate whether first-language heterogeneity in CSCL groups reduces students’ assessments of their own online interaction self-efficacy after having online interaction and communication experiences in the context of their CSCL group (due to experiences of language-based misunderstandings and/or stereotype-related complexities in communication related to the group task).

The moderating role of CSCL activities

The second main interest of our work pertained to the factors potentially moderating the relationship between first-language heterogeneity in CSCL and students’ assessments of their online interaction self-efficacy. Specifically, we investigated whether and to what extent the effects of first-language heterogeneity on self-efficacy acquisition depend upon different types of CSCL collaboration activities. Research concerning group dynamics in virtual teams suggests that similar to cases of face-to-face group collaboration, virtual group activities can be related to a distinction between a task/cognitive space and a social/emotional space (e.g., Han & Beyerlein, 2016; Janssen et al., 2012; Kirschner et al., 2015; Slof et al., 2010). Activities in the task/cognitive space comprise general task-related communication (e.g., Janssen et al., 2012; Straus, 1997), activities related to the sharing of knowledge or information (e.g., González-Navarro et al., 2010; Han & Beyerlein, 2016), coordinating and planning (e.g., Janssen et al., 2012; Massey et al., 2003), or exchanging and agreeing on mutual expectations (e.g., Han & Beyerlein, 2016; Kirschner et al., 2015; Massey et al., 2003). Activities in the social/emotional space, on the other hand, comprise, for example, personal socioemotional communication (e.g., Janssen et al., 2012; Kreijns et al., 2003), developing relationships, trust and a positive group atmosphere (e.g., Branson et al., 2008; Kreijns et al., 2003; Massey et al., 2003), or exchanging and becoming aware of interpersonal differences (e.g., Han & Beyerlein, 2016; Slof et al., 2010).

Although the relative proportion of task-related and socioemotional activities may vary across different phases of collaboration, research pertaining to virtual groups shows that certain behavioral patterns established at the beginning of group work have a persistent influence on subsequent group processes. Building on a meta-analysis of 60 published studies concerning the effects of multinational heterogeneity on collaboration in virtual teams, Han and Beyerlein (2016) argue, for instance, that two types of activities are particularly relevant during the initial phase because they address critical challenges to the establishment of successful virtual collaboration. The first activity is task-related communication, which focuses on issues such as the creation of a joint understanding of the task or addressing misunderstandings. A second process is related to activities associated with getting to know each other. According to Han and Beyerlein, a high investment of time in these activities at the beginning of the collaboration mitigates the effects of social categorization or stereotyping processes within the group. Therefore, combining Han and Beyerlein’s analysis with the self-efficacy perspective outlined above, we investigated whether and to what extent the hypothesized negative effects of first-language heterogeneity on gains in online interaction self-efficacy at the end of the course are stronger for groups that spent relatively little time on task-related communication (e.g., addressing misunderstandings) and/or getting to know each other during the initial phase (e.g., overcoming stereotypes).

The present research

Accordingly, we explored the following main research questions:

-

(1)

Do students in CSCL groups featuring high first-language heterogeneity in terms of the language of instruction exhibit lower gains in online interaction self-efficacy at the end of their collaboration than students in groups with low first-language heterogeneity?

-

(2)

Does the amount of time spent on task-related communication and/or getting to know each other at the beginning of the collaboration mitigate these negative effects of heterogeneity?

To investigate these questions statistically, we first compared students’ gains in CSCL groups with and without first-language heterogeneity. We then developed a moderation model for our pretest–posttest dataset that allowed us to test the moderating effects of our two moderators simultaneously (see Fig. 1). In this model, CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity (based on students’ sociodemographic information) served as the (group score) predictor. The main criterion consisted of baseline corrected individual values of students’ online interaction self-efficacy at the end of the collaboration (i.e., “residual gains”, see Cronbach & Furby, 1970). CSCL groups’ reports of the amounts of time spent on task-related communication or getting to know each other at the beginning of the collaboration served as potential moderators (see Hayes, 2021, Model 2). To eliminate possible confounders, we statistically controlled for additional dimensions of heterogeneity (i.e., heterogeneity in terms of age, gender, and socioeconomic status).

Conceptual moderation model according to model 2 by Hayes (2021). The predictor first-language heterogeneity and the two moderators time spent getting to know each other and time spent on task-related communication are group scores, the criterion gains in online interaction self-efficacy are individual scores

Method

Institutional context

The CSCL assignment was part of an introductory course in the Psychology B.Sc. program at the FernUniversität in Hagen, which is Germany’s largest public research university (including more than 70,000 enrolled students) and represents one of the largest distance education institutions worldwide. The FernUniversität in Hagen awards undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in a manner equivalent to campus-based universities in Germany. The FernUniversität in Hagen employs a blended learning approach that combines print-based study materials with computer-mediated activities and classroom teaching.

Participants and procedure

The data used in this study were collected as part of a larger-scale project to investigate the effects of student heterogeneity in CSCL (Stürmer et al., 2020). The study was conducted in the context of a mandatory course on scientific reading and writing, in which freshmen pursuing a B.Sc. in psychology were assigned a nine-week CSCL task that required them to collaboratively summarize a psychological research paper in their own words in the context of a joint group wiki. After enrolling in the course, the 2844 registered students were randomly assigned to 357 groups consisting of eight students each. The data used for the present analyses were obtained from 1525 students who participated in the accompanying surveys, corresponding to 343 CSCL groups. The total group-level rate of participation was a noteworthy 96% of all CSCL groups included in the course. The average number of students in the 343 CSCL groups who responded to the questionnaire and provided self-report data was four students, with a range from two to eight students (SD = 1.4). In line with the general student population in the FernUniversität’s psychology program, 73.8% (n = 1117) of the students were female, 46.3% (n = 704) of the students were 30 years old or older, and 50.3% (n = 761) were part-time students. A total of 14.3% (n = 216) of the students reported being nonnative speakers of German, 19.7% (n = 297) indicated that they had a migration background, and half of the students (51.7%) indicated that they had a lower socioeconomic status. A total of 44.3% (n = 675) of the students reported having moderate to good levels of experience with virtual learning formats.

Virtual learning context

Each CSCL group engaged in collaboration in a protected virtual course environment via the online leaning platform Moodle. Students were instructed to complete all assigned tasks using the communication tools provided by Moodle (e.g., forums, message service in Moodle). Overall, following De Wever et al.’s (2015) procedures, students created four separate wikis containing separate summaries of the research article’s introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections. These activities thus provided the students with ample opportunities for collaboration. To promote the development of students’ self-regulation skills, supervision and support by instructors or tutors was limited to administrative or technical issues. This approach allowed us to observe and study spontaneous collaboration behavior (i.e., the natural state of affairs).

Measures

The data collected during the CSCL collaboration pertained to different issues included in the larger research project. In the following section, only the measures that are relevant to the present analyses are described.

Students’ demographic characteristics and CSCL groups’ heterogeneity (Measured before group assignment, i.e., precourse)

Before group assignment, students completed a precourse questionnaire including measures of their sociodemographic attributes. The language of instruction in the educational setting of our study was German. First-language status was thus assessed using a dichotomous measure (0 = German, 1 = other than German). Following Harrison and Klein’s (2007) recommendations for studying the effects of heterogeneity, we operationalized CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity in terms of the variety of students’ first-language status in the CSCL group (i.e., the group consisted only of native speakers of German or both native and nonnative speakers of German), and we quantified this variety using Blau’s heterogeneity index (Blau, 1977). Higher scores on this index reflect higher first-language heterogeneity, with a theoretical range between 0 (maximum homogeneity, i.e., groups consisting only of native speakers of German) and 0.5 (maximum variety, i.e., groups consisting of half native speakers of German and half nonnative speakers). To control for the influences of other dimensions of heterogeneity in our statistical analyses, we also calculated Blau’s indices separately for CSCL groups’ heterogeneity in terms of gender (0 = male, 1 = female), age (0 = 30 or younger, 1 = 31 or older), and socioeconomic status (0 = lower, 1 = higher scores on MacArthur’s 10-point subjective socioeconomic status scale; see Hoebel et al., 2015).

Time spent by CSCL groups on task-related communication and getting to know each other (Measured after two weeks of collaboration)

Building on Han and Beyerlein’s (2016) analyses, each student reported the amount of time their CSCL group spent on different group activities during the initial collaboration phase. Among these items, one item focused on CSCL group members’ task-related communication: “In the past week, how much time did your group spend on task-related communication (e.g., regular clarification of task content, clarifying misunderstandings about the task)?”. A second item referred to getting to know each other: “In the past week, how much time did your group spend getting to know each other (e.g., sharing personal information, learning about each other’s differences)?”. For each activity, students indicated the relative percentage of time the group spent on the activity in question during the past week. We calculated separate group scores for time spent on each activity by averaging the corresponding scores for each group member. In so doing, we obtained a more reliable consensus measure of the amount of time that group members spent on these activities than would be possible from individual assessments alone. Group scores for communication related to getting to know each other and task-related communication could range from 0% to 100%.

Online interaction self-efficacy (Measured pre- and postcourse)

To measure the degree to which students perceived that they had the capacity to effectively interact with other students in their CSCL groups, we adapted the six-item “self-efficacy to interact with classmates for academic purposes” subscale of Shen et al.’s (2013) Online Learning Self-Efficacy research instrument. Using separate scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (totally), students indicated their levels of confidence with respect to completing six different social interaction tasks with other students in future CSCL groups (i.e., “Actively participate in online discussions”, “Communicate effectively with other group members”, “Express own opinions respectfully to other group members”, “Respond in a timely manner to the activities of other group members”, “Offer help to other group members when needed”, and “Request help from other group members when needed”). To model changes in students’ self-efficacy expectancies as a course outcome, students completed the identical items precourse as a baseline and at the conclusion of the nine-week collaboration postcourse as an outcome. For each student, we calculated separate pre- and postcourse indices for online interaction self-efficacy by averaging their responses to the corresponding items (Cronbach’s α = .79 precourse and .84 postcourse).Footnote 1

Statistical analyses

We analyzed the data using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 (IBM Corp., 2020). To answer the first research question, repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted to assess precourse–postcourse gains in online interaction self-efficacy. Using the SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2021), we conducted a series of moderation analyses to answer the second research question.

Results

Correlations and descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics and correlations related to the theoretically relevant variables are presented in Table 1. CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity (the main predictor) was significantly and negatively related to postcourse online interaction self-efficacy, r = −.08, p < .01 (i.e., the criterion variable without baseline correction). Furthermore, CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity was also negatively related to students’ evaluations of their time spent getting to know each other (the first potential moderator, r = −.09, p < .01) and positively related to time spent on task-related communication (the second potential moderator, r = .11, p < .01). Time spent getting to know each other and time spent on task-related communication during the initial phase of the collaboration were inversely related to each other, r = −.31, p < .01. Groups spent significantly more time getting to know each other than on task-related communication, Mget = 50.45 (SDget = 17.37), Mtask = 9.07 (SDtask = 7.35), t(1524) = −77.39, p < .001, d = −1.98, indicating that, overall, during the first phase of their collaboration, students focused more on getting to know each other than on task-related communication.

Direct effects of CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity on self-efficacy gains

To test our basic assumption concerning the negative effect of CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity on students’ gains in self-efficacy from precourse to postcourse, we conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA. For this purpose, we dichotomized the measure of the presence of first-language heterogeneity in students’ CSCL groups (0 = no, 1 = yes). We then used this dichotomous coding as the between-subjects factor and the repeated measurement of self-efficacy (precourse, postcourse) as the within-subjects factor. The analysis indicated a significant main effect of the time point of measurement, F(1, 1521) = 195.06, p < .001, η2 = .11, a significant main effect of the group heterogeneity factor, F(1, 1521) = 6.93, p = .009, η2 = .005, and a significant interaction effect between group heterogeneity and time point of measurement, F(1, 1521) = 6.11, p = .01, η2 = .004. As depicted in Fig. 2, in groups without first-language heterogeneity, students exhibited higher increases in online interaction self-efficacy from precourse to postcourse (Mpre = 3.74, SDpre = 0.59 vs. Mpost = 4.03, SDpost = 0.63) than students in groups featuring first-language heterogeneity (Mpre = 3.71, SDpre = 0.61 vs. Mpost = 3.91, SDpost = 0.65). These results confirm the claim that first-language heterogeneity in CSCL groups significantly reduces students’ gains in online interaction self-efficacy. A follow-up analysis of the subsample of students in groups featuring first-language heterogeneity (n = 967 students across 131 groups), for which we compared pre- and postcourse gains in self-efficacy for first- and second-language speakers of German, revealed that these two groups did not exhibit significant differences with respect to the critical language-status main effect, F(1, 965) = 0.52, p = .47, η2 = .001. This finding suggests that first-language heterogeneity in a CSCL group reduces precourse–postcourse online interaction self-efficacy gains independent of the students’ language status.

Time spent on group activities as moderating processes

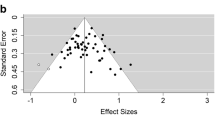

To test the moderation model depicted in Fig. 1, we used the SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2021, Model 2). For this analysis, a central criterion was whether the relevant interaction term became significant, regardless of the presence of a significant total effect, as the direction and magnitude of an effect can depend on a moderator even if the unconditional effect is not significant (Hayes, 2021). Table 2 displays the results of the moderation analysis. As that table indicates, the analysis highlighted the interaction condition, but only with regard to one of the two moderators. In particular, time spent on task-related communication emerged as a significant moderator of the relationship between CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity and self-efficacy gains (for the critical interaction p = .01), while time spent getting to know each other was ineffective (p = .38). Simple slope analyses conducted to decompose the interaction between heterogeneity and time spent on task-related communication revealed that heterogeneity had a stronger negative effect on self-efficacy gains when students’ CSCL group spent a low amount of time on task-related communication than when students’ CSCL group spent a high amount of time on such communication. In fact, when the CSCL groups spent a high amount of time on task-related communication, the effect of first-language heterogeneity was nonsignificant. This finding was true independent of the amount of time that groups spent getting to know each other (see Fig. 3a and b for conditional simple slopes). Overall, our analyses suggested that low amounts of time spent by students’ CSCL groups on task-related communication play a critical role in strengthening the negative effect of CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity on students’ gains in self-efficacy. With respect to the amount of time that groups spent getting to know each other, on the other hand, we observed no significant interaction effect on students’ gains in self-efficacy.

a and b Precourse–postcourse gains in online interaction self-efficacy as a function of first-language heterogeneity (precourse) and time spent getting to know each other (initial phase), under the condition of a) low level and b) high level of time spent on task-related communication (initial phase). Coefficients are unstandardized regression weights. **p < .01, ***p < .001 (two-tailed)

To substantiate the validity of our results further, we replicated the analysis reported above and included the number of respondents per group as an additional control variable, as this number was uneven across groups. Including this variable in the analyses did not change any of the results. The number of respondents received a significant and negative regression weight (b = −0.03, p = .05), but the critical main and interaction effects involving first-language heterogeneity remained virtually unchanged. This lack of change also occurred in the context of an additional analysis controlling for students’ previous experience with virtual learning to account for the predictive value of previous experience, p = .58.

Follow-up analyses of the role of time spent getting to know each other

Our moderation analyses revealed that the amount of time that CSCL groups invested in getting to know each other was ineffective in reducing the negative effects of first-language heterogeneity on online interaction self-efficacy. A possible post hoc interpretation of this observation could be that time spent getting to know each other (rather than working on the task) increases (rather than decreases) perceptions of language-based heterogeneity in the group. The dataset that we used to test our hypotheses provided us with the opportunity to explore this interpretation in further detail by including an additional measure of group members’ subjective perceptions of group heterogeneity in our analyses, which was included for purposes related to the larger research project. Two items (i.e., “Overall, the members of my working group are rather different”, “Overall, the members of my working group are rather similar” (reverse coded)) were assessed in the postcourse questionnaire, and participants rated the items on separate five-point Likert scales with responses ranging from “does not apply at all” to “totally applies”, with higher values indicating higher levels of perceived heterogeneity (interitem r = .69, p < .01). If time spent getting to know each other actually increased (rather than decreased) heterogeneity perceptions, one would expect the relationships between first-language heterogeneity and perceptions of heterogeneity to be more pronounced when CSCL groups spent more time getting to know each other. An exploratory moderated regression analysis featuring CSCL groups’ first-language heterogeneity as a predictor, time spent getting to know each other and time spent on task-related communication as moderators, and perceived group heterogeneity as a criterion corroborated this interpretation (see Table 3). The relevant conditional simple slope diagrams are presented in Fig. 4a and b. First-language heterogeneity had a stronger positive effect on perceived group heterogeneity when students’ CSCL groups spent more time getting to know each other than when they spent less time on this activity. This relationship held independent of the amounts of time that the groups spent on task-related communication (see Fig. 4a and b for conditional simple slopes). In light of these additional findings and in retrospect, time spent getting to know each other in first-language heterogeneous CSCL groups seems to have the paradoxical effect of increasing rather than decreasing perceptions of heterogeneity among group members, which in turn might impair their gains in online interaction self-efficacy.

a and b Perceived group heterogeneity as a function of first-language heterogeneity (precourse) and time spent getting to know each other (initial phase), under the condition of a) low level and b) high level of time spent on task-related communication (initial phase). Coefficients are unstandardized regression weights. **p < .01, ***p < .001 (two-tailed)

Discussion

The present pretest–posttest study investigated a cohort of distance education students over the course of a nine-week CSCL assignment in a course context that required literacy skills and was delivered without active teacher scaffolding or intervention during the course. Our findings show that in such a learning context, first-language heterogeneity in CSCL groups may undermine students’ ability to acquire online interaction self-efficacy, especially with respect to their expectation that they can effectively collaborate and interact with other students for academic purposes (Shen et al., 2013). Previous research has shown the negative effects of cultural and language differences in CSCL with regard to learning outcomes (e.g., Popov et al., 2013; Stepanyan et al., 2014; Usher & Barak, 2020). Our findings show that, independent of students’ own first-language status, when a group featured first-language heterogeneity, students exhibited lower gains in online interaction self-efficacy with regard to interactions for academic purposes at the end of the course than students in groups without first-language heterogeneity. From a practical perspective, these findings are worrisome, as self-efficacy expectations pertaining to a low degree of interaction may lead students to avoid future academic collaboration with other students, especially in online contexts that are characterized by first-language heterogeneity.

Our moderation analysis helped us unravel the social psychology underlying the negative effects of first-language heterogeneity on students’ online interaction self-efficacy gains. In their analysis of the diversity processes operative in virtual collaboration, Han and Beyerlein (2016) emphasized the importance of two distinct group activities during the initial phase, namely, task-related communication and activities focused on getting to know each other. Moderation analyses showed that the negative relationship between first-language heterogeneity and students’ self-efficacy beliefs was significantly attenuated by the amount of time that groups spent on task-related communication at the beginning of the collaboration. In fact, first-language heterogeneity only had a negative relationship with gains in online interaction self-efficacy for academic purposes when students in the group spent little time communicating about the task at hand. Interestingly, when groups spent longer amounts of time getting to know each other, it did not mitigate the first-language heterogeneity effects on self-efficacy gains. This observation is interesting because it seems intuitively plausible that more time to get to know each other would help reduce language-related categorization or stereotyping (see Han & Beyerlein, 2016; van Knippenberg et al., 2004). However, our follow-up analyses, which examined the effect of first-language heterogeneity on group members’ heterogeneity perceptions, indicate that the opposite may be the case. Specifically, we found that when groups featured first-language heterogeneity, a large amount of time spent getting to know each other amplified group members’ perception of intragroup differences. In retrospect, it thus appears that unstructured socioemotional communication in first-language heterogeneous CSCL groups increased (rather than reduced) the salience of language-related social categories (e.g., different nationalities) and associated stereotypes. Although our data appear to be consistent with such an interpretation, future research is needed to explicate and test it in further detail.

Several aspects of our data provide evidence of the robustness of our conclusions. First, our dataset allowed us to test our moderation model in the context of a substantial sample containing more than 340 randomly composed groups representing over 90% of the groups included in the course. We can thus rule out the possibility that our findings resulted from the dynamics of a few nonrepresentative groups that were isolated from the rest of the cohort. Second, we observed moderating relationships in an ecologically valid context, in which, due to the multitude of factors operating in the field, the detection of significant interaction effects is often particularly challenging (McClelland & Judd, 1993). Compared to main effects, moderating effects are typically smaller, even though they still have a significant degree of scientific and practical impact (Aguinis et al., 2005). The moderation observed in the present study pertained to students’ online interaction self-efficacy over a considerable period (i.e., nine weeks), thus indicating relevant and robust results. Third, in our analyses, we controlled for competing effects of CSCL group heterogeneity, namely, group heterogeneity in terms of gender, age, or socioeconomic status, as well as for group size and students’ previous virtual learning experiences. We can thus conclude that the observed pattern of effects did not result from the confounding effects of other potentially influential variables.

Limitations and implications

We must also acknowledge the potential limitations of this study. First, the standard limitations pertaining to drawing causal inferences from nonexperimental research apply (e.g., Wu & Zumbo, 2008). A second issue concerns our dichotomous measure of first-language status. Due to data privacy regulations, for nonnative speakers of German, we did not record students’ specific first languages. Although official student statistics indicate that the majority of nonnative speakers at German universities are students with a Turkish background (Middendorff et al., 2013), the dichotomous nature of our measure did not allow us to draw any further conclusions with regard to specific languages or cultural groups. Third, as language and culture are naturally confounded, we cannot determine the extent to which the observed first-language heterogeneity effects reflect influences of language-related processes, stereotype-related processes or both.

Despite these potential limitations, the data allow for the deduction of some practical implications for the design of interventions. Our research identified a specific risk constellation for CSCL groups, which consists of a combination of high first-language heterogeneity and low task-related communication. A first step in an effective intervention would thus consist of systematic monitoring of group processes during the early phase of the collaboration and the provision of appropriate group feedback concerning potential risks. If necessary, linguistically heterogeneous CSCL groups could then be assisted in increasing their task-related communication, for example, through adapted scripting or scaffolding procedures designed to structure task-related communication (e.g., Popov et al., 2014; Stürmer et al., 2018; Weinberger et al., 2013). Such task-related scripting instructions would be able to prompt CSCL group members, for instance, to focus on task-related (rather than socioemotional) questions, to formulate plans or strategies or to monitor task progress effectively. The advantage of such an empirically informed and group-specific adapted approach would be that it would mitigate negative and unintended effects on low-risk groups, which may therefore perceive such interventions as disruptive interference (i.e., overscripting; see, e.g., Dillenbourg, 2002).

Conclusion

Student bodies at universities are becoming increasingly heterogeneous. This study shows that, independent of their own language status, first-language heterogeneity in CSCL groups can negatively impact group members’ self-efficacy expectations with respect to communicating effectively within groups. Online teachers and instructors should therefore develop an awareness of the fact that first-language heterogeneity in CSCL groups can potentially limit students’ expectations that they can effectively collaborate and interact with other students online. The design of adaptive evidence-based heterogeneity management interventions in CSCL is still in its infancy. In the present research, we hope that we have made a compelling case that it is worthwhile to advance this stream of research.

Notes

Shen et al.’s (2013) Online Learning Self-Efficacy research instrument includes an additional subscale related to students’ general expectations of interacting socially with other students (e.g., developing friendships with other students) in online courses. Empirical analyses show that both subscales are highly correlated with each other (r = .67; see Shen et al., 2013, Table 3). In the present study, because we were interested in the effects of first-language heterogeneity and group activities on learning-related self-efficacy expectations, we decided to measure the specific online self-efficacy component in terms of self-efficacy with respect to interacting with classmates for academic purposes.

References

Aguinis, H., Beaty, J. C., Boik, R. J., & Pierce, C. A. (2005). Effect size and power in assessing moderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression: A 30-year review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.94

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Batalova, J., & Feldblum, M. (2020). Immigrant-origin students in U.S. higher education. A data profile. Migration Policy Institute. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED611278. Accessed Dec 2022

Berg, R. W. (2012). The anonymity factor in making multicultural teams work: Virtual and real teams. Business Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569912453480

Blau, P. (1977). Inequality and heterogeneity: A primitive theory of social structure. Free Press.

Branson, L., Clausen, T. S., & Sung, C. (2008). Group style differences between virtual and F2F teams. American Journal of Business, 23(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/19355181200800005

Cress, U., Rosé, C., Wise, A., & Oshima, J. (2021). International handbook of computer-supported collaborative learning (19th ed.). Springer International Publishing.

Cronbach, L. J., & Furby, L. (1970). How we should measure “change”: Or should we? Psychological Bulletin, 74(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029382

De Wever, B., Hämäläinen, R., Voet, M., & Gielen, M. (2015). A wiki task for first-year university students: The effect of scripting students’ collaboration. The Internet and Higher Education, 25, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.12.002

Dillenbourg, P. (2002). Over-scripting CSCL: The risks of blending collaborative learning with instructional design. In P. A. Kirschner (Ed.), Three worlds of CSCL. Can we support CSCL? (pp. 61–91). Open Universiteit Nederland.

Flanagin, A. J., Tiyaamornwong, V., O’Connor, J., & Seibold, D. R. (2002). Computer-mediated group work: The interaction of sex and anonymity. Communication Research, 29(1), 66–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365020202900100

Giles, H., & Ogay, T. (2007). Communication accommodation theory. In B. B. Whaley & W. Samter (Eds.), Explaining communication: Contemporary theories and exemplars (pp. 293–310). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410614308

González-Navarro, P., Orengo, V., Zornoza, A., Ripoll, P., & Peiró, J. M. (2010). Group interaction styles in a virtual context: The effects on group outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1472–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.04.026

Han, S. J., & Beyerlein, M. (2016). Framing the effects of multinational cultural diversity on virtual team processes. Small Group Research, 47(4), 351–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496416653480

Harrison, D. A., & Klein, K. J. (2007). What’s the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1199–1228. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26586096

Hayes, A. F. (2021). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hoebel, J., Müters, S., Kuntz, S., Lange, C., & Lampert, T. (2015). Measuring subjective social status in health research with a German version of the MacArthur scale. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, 58(7), 749–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-015-2166-x

IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 27.0 [computer software].

Isohätälä, J., Näykki, P., Järvelä, S., Baker, M. J., & Lund, K. (2021). Social sensitivity: A manifesto for CSCL research. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 16(2), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-021-09344-8

Janssen, J., Erkens, G., Kirschner, P. A., & Kanselaar, G. (2012). Task-related and social regulation during online collaborative learning. Metacognition and Learning, 7(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-010-9061-5

Kirschner, P. A., Kreijns, K., Phielix, C., & Fransen, J. (2015). Awareness of cognitive and social behaviour in a CSCL environment: Self- and group awareness in CSCL. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12084

Kreijns, K., Kirschner, P. A., & Jochems, W. (2003). Identifying the pitfalls for social interaction in computer-supported collaborative learning environments: A review of the research. Computers in Human Behavior, 19(3), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(02)00057-2

Kukulska-Hulme, A., & Pegrum, M. (2018). Linguistic diversity in online and mobile learning. In A. Creese & A. Blackledge (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language and superdiversity (pp. 518–532). Routledge.

Lea, M., & Spears, R. (1991). Computer-mediated communication, de-individuation and group decision-making. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 34(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7373(91)90045-9

Massey, A. P., Montoya-Weiss, M. M., & Hung, Y.-T. (2003). Because time matters: Temporal coordination in global virtual project teams. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 129–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2003.11045742

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114(2), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376

Middendorff, E., Apolinarski, B., Poskowsky, J., Kandulla, M., & Netz, N. (2013). Die wirtschaftliche und soziale Lage der Studierenden in Deutschland 2012. 20. Sozialerhebung des Deutschen Studentenwerks durchgeführt durch das HIS-Institut für Hochschulforschung [The economic and social situation of students in Germany 2012. 20th social survey of the German Student Union, conducted by the HIS Institute for Higher Education Research]. Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung.

Morrice, L., Shan, H., & Sprung, A. (2017). Migration, adult education and learning. Studies in the Education of Adults, 49(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2018.1470280

OECD. (2016). PISA 2015 results (volume I): Excellence and equity in education. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en

Popov, V., Biemans, H. J. A., Brinkman, D., Kuznetsov, A. N., & Mulder, M. (2013). Facilitation of computer-supported collaborative learning in mixed- versus same-culture dyads: Does a collaboration script help? The Internet and Higher Education, 19, 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.08.002

Popov, V., Noroozi, O., Barrett, J. B., Biemans, H. J. A., Teasley, S. D., Slof, B., & Mulder, M. (2014). Perceptions and experiences of, and outcomes for, university students in culturally diversified dyads in a computer-supported collaborative learning environment. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.008

Shen, D., Cho, M.-H., Tsai, C.-L., & Marra, R. (2013). Unpacking online learning experiences: Online learning self-efficacy and learning satisfaction. The Internet and Higher Education, 19, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.04.001

Sinha, S., Rogat, T. K., Adams-Wiggins, K. R., & Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2015). Collaborative group engagement in a computer-supported inquiry learning environment. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 10(3), 273–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-015-9218-y

Slof, B., Erkens, G., Kirschner, P. A., Jaspers, J. G. M., & Janssen, J. (2010). Guiding students’ online complex learning-task behavior through representational scripting. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 927–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.02.007

Spears, R. (2017). Social identity model of deindividuation effects. In P. Rössler (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of media effects (pp. 1–9). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0091

Spears, R., Postmes, T., Lea, M., & Wolbert, A. (2002). When are net effects gross products? The power of influence and the influence of power in computer-mediated communication. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00250

Stepanyan, K., Mather, R., & Dalrymple, R. (2014). Culture, role and group work: A social network analysis perspective on an online collaborative course: SNA perspective on an online collaborative course. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 676–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12076

Straus, S. G. (1997). Technology, group process, and group outcomes: Testing the connections in computer-mediated and face-to-face groups. Human–Computer Interaction, 12(3), 227–266. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327051hci1203_1

Stürmer, S., Ihme, T. A., Fisseler, B., Sonnenberg, K., & Barbarino, M.-L. (2018). Promises of structured relationship building for higher distance education: Evaluating the effects of a virtual fast-friendship procedure. Computers & Education, 124, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.015

Stürmer, S., Raimann, J., Reich-Stiebert, N., & Voltmer, J.-B. (2020). Diversity adapted CSCL in higher distance education (DivAdapt): A multi-method longitudinal study on diversity effects in CSCL with 1525 students in 343 groups [dataset]. FernUniversität in Hagen.

Usher, M., & Barak, M. (2020). Team diversity as a predictor of innovation in team projects of face-to-face and online learners. Computers & Education, 144, 103702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103702

van Knippenberg, D., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Homan, A. C. (2004). Work group diversity and group performance: An integrative model and research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 1008–1022. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.1008

Van Wyk, J., & Haffejee, F. (2017). Benefits of group learning as a collaborative strategy in a diverse higher education context. International Journal of Educational Sciences, 18(1–3), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/09751122.2017.1305745

Weinberger, A., Marttunen, M., Laurinen, L., & Stegmann, K. (2013). Inducing socio-cognitive conflict in Finnish and German groups of online learners by CSCL script. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 8(3), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-013-9173-4

Wu, A. D., & Zumbo, B. D. (2008). Understanding and using mediators and moderators. Social Indicators Research, 87(3), 367–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9143-1

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted in the framework of the Center of Advanced Technology for Assisted Learning and Predictive Analytics (CATALPA) of the FernUniversität in Hagen, Germany.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The present work was approved by the local ethics committee of the FernUniversität in Hagen (Approval-ID: EA_103_2019).

Informed consent

We confirm that any participant in our work has given informed consent by clicking a button on an online (written) consent form.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reich-Stiebert, N., Voltmer, JB., Raimann, J. et al. The role of first-language heterogeneity in the acquisition of online interaction self-efficacy in CSCL. Intern. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn 18, 513–530 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-023-09411-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-023-09411-2