Abstract

Through close analyses of the interaction that takes place between students and facilitators, this study investigates the instructional use of video in post-simulation debriefings. The empirical material consists of recordings of 40 debriefings that took place after simulation-based training scenarios in health care education. During the debriefings, short video-recorded sequences of the students’ collaboration in the scenarios were shown, after which the facilitators asked the students questions about the teamwork and their performance as displayed in these sequences. The aim of the study is to show: a) how the video is consequential for the ways in which the students talk about the teamwork and their own performance; b) how the facilitators’ questions guide the students’ contributions and collaborative sense making of prior events. Regularly, the facilitators’ questions were posed in terms of “seeing”. The design and sequential environment of the questions made it relevant for the students to comment on how the displayed situations appeared audiovisually and how these appearances contrasted with their experiences from the situation. In this way, the video enabled the students to talk about their own conduct, including their collaboration with their peers, from a third-person perspective. The study highlights the central role of instructions and instructional questions in the debriefings, how the video was used to make the students reconceptualise their performance together with others, and the importance of contributions from fellow students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study investigates video-supported feedback in post-simulation debriefings. Such debriefings can be defined as feedback conversations during which learners jointly discuss and reflect on their collaborative performance in a preceding simulation-scenario under the guidance of a facilitator. In line with the rapid development of technologies for video recording in the past decade, video feedback has become a common feature of debriefings. As maintained by Fanning and Gaba (2007, p. 122), “video playback may be useful for adding perspective to a simulation, to allow participants to see how they performed rather than how they thought they performed, and to help reduce hindsight bias in assessment of the scenario.” This study sets out to investigate what formulations like these might mean in terms of actual practice: in other words, how additional perspectives are made relevant in the debriefings; how participants orient to distinctions between appearances and experiences; and how students and facilitators assess the performances in the simulation scenarios. Previous research of video-supported debriefings has largely been carried out in the simulation research area, with a focus on the measured success or perceived effectiveness of this kind of feedback (e.g., Byrne et al. 2002; Grant et al. 2010; Hamilton et al. 2011). In contrast, the present study investigates the interaction that takes place between students and facilitators as they jointly analyze and reflect on video recordings of the students’ performances in the simulation scenarios during the investigated debriefings.

Using video for self-reflection and learning

For almost half a century, video has been used to provide feedback on skilled or novice performance and to promote self-reflection, self-assessment, and self-confrontation (cf. Fuller and Manning 1973). There seems to be a consensus in the research literature that video can be an efficient educational tool if it is used in an appropriate way. A meta-study of video-supported feedback in education and training concludes that video feedback is “an effective method that contributes to a wide range of key professional skills” (Fukkink et al. 2011, p. 56). The instructional value of video-supported feedback is particularly emphasized in areas such as medicine and sport (e.g., Farquharson et al. 2013; O'Donoghue 2006); that is, areas where skills and competence are visibly accessible through recordings of embodied actions. Video is also frequently used to support discussions about communication and professional conduct in the training of psychotherapists (Haggerty and Hilsenroth 2011), teachers (Tripp and Rich 2012; van Es 2009), and doctors (Beckman and Frankel 1994; Kurtz et al. 2005). By watching themselves on video, it is argued, “professionals are able to improve their receptive, informative and relational skills” (Fukkink et al. 2011, p. 56).

Although several studies have demonstrated that video feedback can play an important role for student learning, not all uses of video are equally beneficial. The importance of appropriate guidance is frequently stressed and it is argued that “participants who are given insufficient pointers about what to focus on may find it hard to concentrate on important, substantive aspects and may be distracted by superficial impressions or a one-sided focus” (ibid.) These results of research seem to apply to instructional uses of video more generally. Derry et al. (2002) and Zottmann et al. (2012) investigate the use of video in case-based, pre-service teacher training and find it to be associated with increased post-test performance. As Zottman et al. points out, for instance, “digital video cases can be used to foster central aspects of analytical competency, which in turn is strongly connected to the professional competency of teachers” (p. 529). This result is qualified with a caveat: “case-based learning in teacher education can and should be optimized by means of additional instructional support.” (ibid.).

In the study by Zottman et al., the additional support takes the form of added perspectives provided by comments by the actors involved in the case. When students are watching recordings of their own performance, and not the performance of some other party, there is a sense in which the video itself provides an additional perspective. A common argument for video-supported feedback and reflection is that the video allows “participants to look at themselves ‘from a distance’ and with space for reflection, thereby giving them a realistic picture of their own skills, or self-image” (Fukkink et al. 2011, p. 46). In the context of teacher education, for instance, video is claimed to provide “student teachers with specific information for the analysis and evaluation of their classroom teaching performance, from an observer perspective, with an unlimited access.” (Kong et al. 2009, p. 546). However, other researchers emphasize that video is “an inherently ambiguous and incomplete stimulus that invites reaction and speculation ranging far beyond the information that is potentially available in the video clip itself” (Erickson 2007, p. 152). Although video provides another perspective of the activity, and enables the participants to examine their own conduct, instructors or facilitators are still central in shaping discussions and student perceptions. It is argued, for instance, that instructional questions can focus the attention of the participants “while watching the footage, and to enable them to stay ‘on track’ and address the intended topic during the discussion” (Borko et al. 2011, p. 175).

Investigating the concrete use of video for collaborative learning

As noted by Zahn et al. (2012, p. 260), “video is one of the most popular forms of educational media across the curriculum and plays an increasingly important role in classroom learning”. Despite the popularity of video, however, “systematic research addressing video as socio-cognitive tool for collaborative learning is very scarce” (p. 260). With their focus on measured success or perceived effectiveness of video based feedback, studies in the field of simulation research provide evidence that video is a useful tool and demonstrate the importance of additional guidance. However, these studies do not examine the concrete ways in which video can be used to support collaborative learning: how video is consequential for student reflection, how additional perspectives are made relevant, or how the questions and instructions of facilitators guide student perception. According to Stahl (2012), there are strong arguments for adopting an ethnomethodological approach to the analysis of computer-supported collaborative learning. In particular, ethnomethodology suggests ways to “observe and report on the ability of given technologies and pedagogies to mediate collaborative interactions between students in concrete case studies” (p. 2–3). Koschmann (2013) similarly maintains that conversation analysis (CA), an approach closely associated with ethnomethodology, can contribute to the understanding of collaborative learning by showing “just how collaboration and instruction are carried out together” (p. 159).

While there are no ethnomethodological or conversation analytic studies that investigate how video is used in post-simulation debriefings, or other relevant settings of computer supported collaborative learning, there is a growing body of work that investigates the social organization of instructional practices that involve video (cf. Broth et al. 2014a). As shown by these studies, talk and gestures are mobilized to provide for a certain understanding of the video, and the additional perspective provided by the video is often consequential for the ongoing activity. In an early and influential study on professional vision, Goodwin (1994) shows how lawyers and expert witnesses in a courtroom organize “the perceptual field provided by the videotape into a salient figure” (p. 620) and how they thereby instruct the jury to see portrayed events in a particular way. In the context of reality TV parenting shows, McIlvenny (2011) analyzes how professionals use video to confront parents with evidence of their own behavior. Rather than being “simply a tool for remembering,” the video is used “to prompt reflection and a perspective shift by the parent(s)” (p. 281). Lindwall et al. (2014) investigate how live video of root canal fillings is used in dental education seminars. In interviews, the students expressed that they appreciated the recordings because they showed “what it really looks like”; but in the actual seminar “differences between what appears in the recordings and what the dentists really see and do were recurrently raised” (Lindwall et al. 2014, p. 162; cf. Rystedt et al. 2013).

Informed by the studies presented above, as well as additional ethnomethodological and conversation analytic work in CSCL (e.g. Greiffenhagen 2012; Koschmann 2013; Lymer et al. 2009; Stahl 2012), the present study contribute to the field with empirically grounded findings regarding how collaborative video analyses, as jointly performed by teachers and students during the post-simulation debriefings, brought attention to certain aspects of the students’ interprofessional teamwork.Footnote 1 The empirical material of this study consists of recordings of 40 video-supported debriefings. The simulation scenarios were designed so that the students could practise interprofessional teamwork with a particular emphasis on communication and collaboration skills. In the simulation training, collaboration was thus not only a means to an end; to collaborate in interprofessional teams was also what the students were supposed to practise and learn. During the debriefings, short video-sequences of “key events” of the scenarios were shown, after which the facilitators asked the students to jointly discuss and reflect on their performance in the scenarios. The aim of the study is to show: a) how the video is consequential for the ways in which the students talk about the teamwork and their own performance; b) how the facilitators’ questions guide the students’ contributions to the discussion and their collaborative sense making about prior events.

The setting

The study examines post-simulation debriefings that were part of eight one-day simulation practices and which took place at a simulation center at a Swedish university hospital. In this training, medical- and nursing students in the final phase of their educational programs, worked in mixed groups to practise interprofessional teamwork. Experienced facilitators who were either medical doctors or specialist nurses led the training. In the simulation scenarios, the student groups jointly handled different emergency patient cases of a rather basic character, such as managing respiratory arrest and allergic chock. While proper treatment of the patients was regarded as important, the main aim of the training was for the students to practise so called non-technical skills; that is, interpersonal and cognitive skills “not directly related to the use of medical expertise, drugs or equipment” (Flin et al. 2003, p. 2). During the simulation-scenarios, the students were required to conduct a structured examination of the patient, while maintaining a shared view of the patient’s condition, and thereby practise teamwork, collaboration, communication, and leadership. As part of this, certain communication techniques that are well established within healthcare were emphasized, including SBAR, speak up and closed loop communication. Footnote 2

Each one-day simulation practice included five simulation sessions, each of which was organized as a sequence of briefing (2–5 min), scenario (15–20 min), and debriefing (30–40 min). The briefings consisted of short introductions to the upcoming scenarios. The students were divided into groups of 4–8 participants, 2–4 of whom took part in each scenario while the others observed the scenario via live video. The scenarios were conducted in authentically equipped wardrooms, and they were based on a full-scale computerized mannequin. An operator and a facilitator controlled the equipment from a control room next to the simulation room. For feedback purposes and to enable peer observation during the scenarios, all simulation scenarios were video-captured with multiple cameras. Immediately after each simulation scenario, a debriefing was held in an adjacent room.

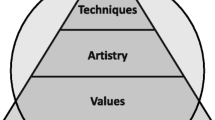

In line with how debriefing is described in the simulation literature (cf. Fanning and Gaba 2007; Lederman 1992), the investigated debriefings served as forums for collaborative discussions and analyses of the preceding simulation exercises. In the investigated setting, the debriefings were based on a specific model for debriefing that was intended to structure the discussions and optimize learning and reflection. The model was organized around three main phases: description, analysis, and application (cf. Steinwachs 1992). The first phase started with a so-called “blow out,” in which each of the students who had participated in the scenario was asked to name one feeling that he or she thought was most prominent after the scenario. They were then asked to provide a brief and factual description of what had happened in the scenario. This was followed by the so-called “analysis phase,” which was the most extensive part of the debriefing. This phase was devoted to joint discussion and analysis of the students’ conduct in the scenario. The debriefings were concluded with the “application phase,” in which the students were asked to briefly summarize what they had learned from the scenario. In accordance with the structure specified by the model, the debriefing discussions focused primarily on what had worked well in the simulation scenarios and how things could be improved, rather than on aspects that had not gone well. As explained by the facilitators in the investigated setting, the rationale for doing so was to make the students aware of what actions and routines that had been successful so that they could maintain those as they entered their future professional practices.

As an element of the debriefings, short video clips were displayed to the students to promote in-depth discussions and reflections on certain “key-events” of the simulation exercises. Except for a few occasions when the technology did not work properly, video clips were displayed and discussed in all the 40 debriefings. The facilitators typically selected one short clip (approximately one to three minutes in length) of a situation in which the students successfully performed actions included in the learning goals of the training, such as SBAR-reporting, speak up or closed loop communication. The video clip was introduced in the analysis phase of the debriefing by the facilitator saying something about the aspects of teamwork and collaboration on which the students were expected to focus when watching the clip. The recordings created by the video-capture system displayed a mixed-image view of the video streams from the three cameras in the scenario room and the image of the patient monitor, which allowed for close observations of various aspects of the scenarios. After the clip was shown, the students were asked to come up with comments and reflections on their collaborative work in the video clip (see Fig. 1).

Methods

As part of the research project, the briefings and the simulation scenarios were video recorded with one camera with external microphones and the debriefings were video recorded with two cameras with external microphones. The video recordings of the debriefings constitute the main empirical materials for this study, and the recordings of the briefings and scenarios have been used mainly to gain a background understanding of how the simulation exercises were carried out. In total, 40 debriefings, between 30 and 40 min in length, were recorded and partially transcribed according to the conventions developed by Jefferson (1984). The study focuses on three episodes that took place after a video clip had been displayed, in which the video was consequential for how the students and the facilitators talked about the students’ teamwork and collaboration in the scenario. The three episodes were selected so as to illustrate recurrent phenomena in the larger corpus.

In this study, like in the research reported in the volume by Broth et al. (2014b), the use of video is both a topic and a resource. On the one hand, the study provides detailed analyses of how video is consequential to the organization of the debriefings. On the other hand, video is also consequential to how the analyses of the study are conducted. Arguing for the merits of recorded data in social science, Heritage and Atkinson (1984) maintain that:

the use of recorded data serves as a control on the limitations and fallibilities of intuition and recollection; it exposes the observer to a wide range of interactional materials and circumstances and also provides some guarantee that analytic conclusions will not arise as artefacts of intuitive idiosyncrasy, selective attention or recollection, or experimental design. (p. 4)

With its emphasis on the limits of recollection and intuition, this quoted passage has parallels with the arguments for the use of video in debriefings outlined in the introduction (cf. Fanning and Gaba 2007, p. 152). Although the use of video in itself provides no guarantee against intuitive idiosyncrasies or selective attention, the analyses reported here would not have been possible without the use of recorded data. As argued by Hindmarsh and Heath (2007, p. 156), video “provides unprecedented access to the fine details of social action” and thereby “opportunities to discover and analyze phenomena that hitherto were unavailable to analysis.” The combination of recorded data and detailed transcripts also makes it possible for a reader to examine whether the analyses manage to explicate the episodes based on the recorded data and whether these analyses provide grounds for the analytical claims that are made (cf. Koschmann 2013, p. 150; Sacks 1984, p. 26). In the debriefings, the facilitators and the students presented, challenged, and negotiated interpretations of the students’ collaborative work in the scenarios. How they did this, and the interpretative work involved, provide this study with its empirical material.

Besides being a video analysis of a video analysis, this study sets out to analyze students and facilitators analyzing each other’s actions. The students’ contributions in the debriefings reflect how they understood their joint performance in the scenarios, but also how they understood prior contributions in the debriefing. In line with this, and in addition to the aim of investigating how the video is consequential to the interaction in the debriefing, special attention is directed to how the students understand the contributions of the facilitators, and thus how these contributions guide the conduct of the students. As repeatedly shown in studies of talk-in-interaction, utterances in conversation are organized into turns-at-talk in which each successive utterance provides conditions for the production of a relevant next. The next utterance, in turn, displays an analysis of the prior utterance in the way it responds to it; for instance, by responding to a previous utterance with an answer, it becomes apparent to the co-participant, as well as to the analyst, that the prior turn was treated as a question. While this, in the first place, is central to the progression of interaction and establishment of intersubjective understanding, it also provides the researcher with “a proof criterion (and a search procedure) for the analysis of what a turn's talk is occupied with” (Sacks et al. 1974, p. 729).

Analysis

In the following, three short fragments are presented and explicated in detail. A finding from the analysis of the 40 debriefings is that the video enables the students to make comments on their own as well as other students’ performances delivered from a third-person perspective. Another central finding is that the design and sequential environment of facilitators’ questions and comments made it relevant for the students to discuss how the displayed situations appeared audiovisually and how these appearances contrasted with their experiences from the situation. Connected to this, it is notable that the video is used as a resource in attempts to change the students’ perceptions of their own implementation of aspects of teamwork and collaboration in the scenario. The three fragments that are presented here have been selected from the larger corpus because they illustrate different aspects of the more general findings in concrete detail.

All three fragments take place immediately or closely after the facilitator has shown a video clip from the preceding scenario and in all cases the video constitutes a common point of reference for the discussions. The fragments begin with the facilitator asking a question of the students: “Do you see something that works well here?” (Fragment 1), “Do you have the same sense after you have seen this?” (Fragment 2), and “What did you think about the mood in the room then?” (Fragment 3). The ensuing discussions then involve different aspects of the students’ collaborative work in the scenarios: clear communication (Fragment 1), reporting according to SBAR (Fragment 2), and calm and structured collaboration (Fragment 3). Despite differences between fragments, the central role of the video, the way that the teacher guides the students through pedagogical questions, and the focus on communicative and collaborative skills are central in all three episodes. To achieve this, the facilitators request responses that involve positive assessments based on the video. They ask the students to describe” something that works well” (Fragment 1) and to contrast previously expressed negative perceptions of their conduct with the supposedly correct performance shown on the video (Fragments 2 and 3). In two of the sequences (Fragments 2 and 3), moreover, other students join the facilitators in attempting to convince students who participated in the scenarios to reconceive their own participation.

A third person perspective on one’s own actions

The first fragment begins immediately after a short video clip from the recording of the preceding simulation scenario had been displayed. In the simulation scenario, which was the first of the day, two nursing students (NU1 and NU2) and one medical student (ME2) had taken part, whereas the other students (one medical student and three nursing students) observed the scenario via live video in the debriefing room. In the displayed video clip, the medical student had just entered the simulation room, and the two nursing students delivered a handover report about the patient’s condition. They also talked to the patient, trying to get information about whether he had urinated that day. The debriefing was led by two facilitators who sat at one end of the table facing the video screen (see Fig. 2). The students sat on the sides of the table.

After the facilitator’s initial “okay,” which marks the movement from watching the video to talking about what was shown, the students turn away from the projector screen and some small talk and laughter ensue (not represented here). The facilitator then continues by providing a short motivation for showing the clip: “we want to show a little about u::h ho:w you work together” (line 108). Despite its general formulation, the utterance still expresses that there was a pedagogical rationale for selecting this particular clip and that the clip is used as an example of the ways that the students “work together.” After a short pause, the facilitator begins to formulate a question that ties to his previous utterance “what what (do you) thi-”, which subsequently, through a self-repair, is reformulated as “did you see something that you thi:nk works well here” (line 110). Whereas the aborted question seems to solicit a mere opinion (“what what (do you) thi[nk]”), the reformulated question is phrased in terms of seeing and thus makes relevant for the students to comment on visible aspects of their conduct in the displayed situation that they think “work well”. Although the facilitator provides an initial gloss of how the video clip should be understood – it displays a situation in which the students’ collaborative work “works well” – the students must nevertheless work out what “work together” and “work well” might mean in terms of the scene that was displayed in the video clip.

The facilitator does not allocate the next turn to any particular student, and his question is followed by a rather long pause before one of the nursing students self-selects as the next speaker. By addressing in positive terms how the student thinks that they looked while they stood around the patient and talked to each other, the answer is responsive to the conditions set by the facilitator’s question. What can be noted, however, is that by saying that the students “nevertheless” looked “sort of u:h (.) .ptk calm” as they were talking to each other, the positive assessment is phrased as a discovery rather than something to be taken for granted, and it can thus be heard to contrast with the student’s previous experience of their collaborative work in the scenario. The student continues to characterize what was working well by saying that they, as a group, were “talking loud.” Here, she makes clear that this is a positive characterization by orienting to a potential ambiguity – that their “talking loud” did not indicate that they were panicking or talking “in an unpleasant way for the patient”, but that it involved exchanging information with each other and asking questions to the patient about his condition (lines 116–117, 119–120). By doing, she provides a specification of the facilitator’s “something that you thi:nk works well” in terms of the audiovisual aspects of their collaborative performance.

After having commented on how the group communicated with one another (lines 115–119), the nursing student turns to what she saw of herself: that she “nevertheless” thought that she “looked nice” while she was listening to what the other students said (line 120). In contrast to the earlier delivered characterizations, the positive self-assessment is treated as laughable by the other students. As the nursing student produces the description, the medical student (ME2) who sits opposite to her makes a face, and one of the other nursing students starts to laugh loudly (line 122). Unlike the attributes that were used in the nursing student’s previous talk, looking calm and talking loud, her comment that she looked nice could potentially be heard as an assessment of her personal characteristics rather than of her professional conduct. However, while the laughter of the peers displays an appreciation of the positive self-talk as humorous or non-serious (cf. Jefferson 1979; Glenn 2003), the nursing student does not acknowledge their laughter as sequentially relevant responses. Instead, the laughter occasions an account by the nursing student that specifies the initial positive assessment “I looked nice” by further describing her visual appearance and conduct in the situation: she looked “calm”, she attended to the patient, and she was “attentive” to what the other students said – aspects that are all of relevance for well-functioning collaboration in a team. In response, the laughter of the peers is replaced by tokens of acknowledgement.

As illustrated in Fragment 1, the video clip is used as a common point of reference in the interaction that takes place after it has been replayed. The focus on the audiovisual aspects of the students’ collaborative work in the scenario is established through the facilitator’s question and maintained throughout the responding nursing student’s answer. Although the nursing student has a first-hand experience of the displayed situation, she manifestly positions herself as an observer and phrases her comments in terms of how her own and the other students’ conduct appear on video: “we look sort of calm”, “we stand around the patient ‘n’ like talking loud”, “I nevertheless thought I looked nice”, “I looked calm”, and “I was very like attentive to (0.5) to listen to what we sai:d”. It is thus clear that the video is consequential for the ways in which the students’ actions and interactions are talked about. By showing how the students’ collaborative work appeared from a third-person perspective, the video clip gives an additional perspective of how they managed to carry out the teamwork activities that were to be practised in the scenario. However, the relevance of noticing and talking about their conduct in this way is not provided by the video alone. As illustrated by the fragment, the contribution of the nursing student is decidedly responsive to the conditions set by the way that the facilitator characterizes the clip and asks the initial question.

The video as evidence

Fragment 2 is taken from another debriefing, which included a different group of students and another facilitator. In the beginning of this debriefing, one of the nursing students (NU2) expressed strong dissatisfaction with her own performance in the scenario. Later, the facilitator presented a video clip that portrayed a situation in which the nursing student (NU2) delivered a handover report to two students who had just entered the simulation room. After having displayed the first part of the video clip, which showed how the nursing student reported the patient’s condition by saying that the patient did not have clear airways and that she was unconscious, the facilitator paused the video to say that he thought that it was a very clear situation report.Footnote 3 The video was then started again, and the rest of the clip displayed how the nursing student gave a more detailed report as the medical student (ME1) entered the simulation room. After the video clip had been shown, the facilitator turned towards the nursing student (NU2) and asked her if she had any comments on the clip. The nursing student responded that she recently had been through a similar situation during her internship, which did not turn out well. She said that the patient case in the simulation scenario had reminded her of this previous situation and had given her a bad feeling. After this initial comment, the nursing student expressed her dissatisfaction with her own performance in the scenario. She maintained that she thought that she had “destroyed everything” since she had not been structured in her actions, that she had delivered her report in “a strange way,” and that she had not “kept track of anything.” As a response, the facilitator posed the question on line 201 in Fragment 2.

Fragment 2 begins with a question from the facilitator (line 201) that is occasioned by the nursing student’s (NU2) prior negative assessments of her own performance in the scenario. The question asks whether the nursing student has the same senseFootnote 4 after having seen the video clip. When the facilitator poses the question, he leans forward, gazes toward the nursing student, and points at the projector screen where a still image of the last frame of the video clip is still displayed. Given that the video showed how the nursing student gave a handover report, and given that the facilitator has already pointed out that the report was very clear, the question projects a negative response acknowledging that the student does not have the same sense as before watching the clip (cf. Koshik 2002).

The initial part of the nursing student’s response, her “u::hm: noe:h,” could be heard as a somewhat reluctant answer in line with the preference of the question, as in no I don’t have the same sense after having seen it. But instead, the student’s utterance develops into a rejection of the invitation that is implied in the facilitator’s question. In her account of the rejection, the student makes a self-repair “noe:h because you haven’t see:n- (.) shown everyth(h)ing.” Both the original formulation and the repair are made in visual terms (i.e. seen and shown). In addition, the repair is responsive to the fact that the facilitator has seen the whole scenario as an observer, whereas only a short clip was shown in the debriefing. In this fragment, the video is given a role as evidence by both the facilitator and the student. Before the video clip was shown, the student was not convinced by the facilitator’s arguments that she did well. When she is presented with a clip that, according to the facilitator, shows that she is delivering a good report, she counters this, not by saying the clip or the facilitator’s interpretation of it is wrong, but by claiming that the video clip does not show everything. Her argument is thus that the selected sequence is not representative of and does not provide sufficient grounds for changing her impression of her performance in the scenario at large.

In the subsequent attempts to convince the student that the report was delivered in a satisfactory manner, the facilitator, and later her fellow students, explicitly orient to what the video showed. In his initial question, the facilitator does not specify what it is that supposedly would change the student’s impression of her own performance. Already in overlap, however, the nursing student’s initial response is elaborated on by the facilitator who refers to the report (line 203). After the student’s account of why her impression has not changed, the facilitator makes another attempt to direct her attention toward the situation displayed in the video clip by saying that the report was what he had planned to show (line 205). Like in Fragment 1, there is here a partially unstated pedagogical rationale for the selection of the video clips: the facilitators use the video to show something, even thought they do not specify exactly what this something is. In the previous case (Fragment 1), the students were provided a framework for assessing whether what they saw “worked well”, but the facilitator did not specify what part of the teamwork the students should focus on. In this case, the facilitator’s presentation of a rationale raises a specific part of the collaborative activity “the report”, but that this “worked well” so far remains implicit. The presentation of the rationale gets some uptake by the nursing student. In its sequential position, however, her “yeah okay” acknowledges the facilitator’s stated intention for showing the clip, and not that she has changed her impression of her performance.

At this point, one of her fellow nursing students breaks in with an explicit assessment of the report, “but if you see that report now, then don’t you think that it was clear?” (line 207) With the inclusion of the disjunction markers but and now, the utterance marks the difference between the expressed perception and what they now have seen on the screen. This orientation to the visual evidence of the video, together with the negative interrogative syntax used, strongly suggests agreement as the appropriate response. The question does not just ask what the student thinks about her own performance, but invites her to agree with a positive assessment of the report. In this way, the utterance displays an understanding of what the facilitator has attempted but not achieved – that the facilitator has used the video to convince the nursing student to reconceive her performance in more positive terms. That the project here is convincing rather than asking is also shown in the way the sequence proceeds. Instead of waiting for a response from the student to which the interrogative turn is directed (it is the singular you in line 207), the student who formulated the “question” responds to it herself by upgrading the assessment of the report: it is not just “clear,” but “crystal clear” (line 208). In overlap with this assessment, a medical student who participated in the scenario joins the appraisal of the report: first through the assessment “very clear” and then with the upgraded “spot on for that matter” (line 211).

By showing the video of a key event of the scenario, that is, a handover report, and posing the initial question, the facilitator sets the agenda of the sequence. However, while some of the educational research literature treats classroom interaction as talk between two parties, a teacher and a cohort of students (cf. Payne and Hustler 1980), this is clearly not applicable here. Instead, the fragment shows how one of the nursing students and one of the medical students join the facilitator in a collaborative attempt to convince the student who made the report to re-evaluate her own performance. One can also note how the parties orient to their different positions with regard to this performance. The medical student (ME1) was the recipient of the report in the scenario. Reflecting the fact that she had “unmediated” access to the report, her assessments are done without any evidentials or hedges (line 209). This contrasts with the qualified account by the nursing student (NU5), who claims to not have experienced the report “in there” since she at that point “was doing something else” (lines 210–211). The grounds for her positive assessments are instead located in the performance, as shown in the video: “now when I watch here” (line 212). It is unclear whether the nursing student who did the report finally accepts the assessment of her fellow students. Her “nah okay” is ambiguous in this regard. What is clear, however, is the central role of the video in the treatment of the performance in the scenario. It is also clear that the video is used as part of a particular instructional agenda, where the facilitator, in collaboration with other students, might use the video to convince a student to reconceptualise her experience. Both these observations are relevant in the next and final sequence.

Appearances and the reconceptualisation of experiences

Fragment 3 is taken from yet another debriefing with a different group of students and another facilitator. Two nursing students (NU2 and NU3) and one medical student (ME1) took part in the scenario that is discussed in the next fragment, whereas the other students observed it via live video. In the video clip displayed in the debriefing, the simulated patient had started to lose consciousness, and the students had placed an oxygen mask to ease the breathing. As the oxygen saturation of the blood increased, one of the nursing students (NU2) called for the medical student’s (ME1) attention. Before displaying this clip, the facilitator told the students to think about the atmosphere in the room and how they shared information with each other. After the video clip had been displayed, the facilitator asked the students if they had any spontaneous thoughts about the strategies that they had used to transfer information among one another. One of the medical students who did not partake in the scenario (ME2) mentioned the situation in the video clip, and said that he thought the nursing student (NU2) notified the medical student (ME1) about the patient’s increased oxygen saturation in a good way. After upgrading the positive assessment of the nursing student’s performance by referring to it as a “nice speak up”, the facilitator continues the discussion on the video clip by posing the question that is represented in the beginning of Fragment 3 (line 301).

The facilitator begins the sequence by returning to an issue that she raised before she played the clip: “what did you think abou:t the atmosphere in the room then,” (line 301). The question is clearly instructional, and it projects a limited set of preferred answers (calm, harmonic, relaxed and the like), but it is nevertheless different from the so-called known-information questions (cf. Mehan 1979), which typically have a single correct answer. Although the plural “you”/“ni” (line 301) could be heard as addressing the whole group, the facilitator directs her gaze specifically at the students who participated in the scenario, thereby making them the primary recipients of her question (cf. Lerner 2003).Footnote 5 During the rather long pause that follows, none of these students indicate that they are going to respond, and eventually a nursing student (NU1) who did not partake in the scenario answers the question by saying “it was very calm.” The minimal response by the facilitator in the next turn sounds more like a token of continued recipiency than acknowledgement, and her gaze continues to wander between the students who participated in the scenario, as if the question still awaits its appropriate uptake by them. Given that the facilitator had asked the students to think about the atmosphere in the room when introducing the clip, and that she now returns to the issue after the clip has been played, her initial question can relevantly be heard as talking about what the students have seen and heard. However, in contrast to the questions that initiated the prior sequences (Fragments 1 and 2), which were explicitly phrased in terms of seeing, the actual formulation does not have the same explicit orientation to the video.

Because the nursing student who first responded to the facilitator’s question (NU1) had only watched the video of the performance in the scenario, her assessment, although stated without any evidential markings, is clearly made from the position of an observer. This fact, and the relevance of a response from another point of view, is raised by one of the nursing students (NU2) who participated in the scenario. The utterance (line 307) starts off as an agreement with the other nursing students’ observations, but it then qualifies the original observation by pointing out that it was done from a certain perspective: “it really looked like that £on the video£ a(h)t leas(h)t”. Even though the calm appearance in one sense is acknowledged, the utterance and the embedded laughter suggest that it might just be the “looks.” After an exchange of glances and laughs between the nursing student and the medical student (ME1) who were part of the scenario, followed by a token of agreement by the facilitator (line 308), the medical student, with a smiley and perhaps somewhat ironic voice, agrees with the nursing student’s qualified account “yeah it (was) very (.) relaxed” (line 309). At this point, there are two portrayals of the situation depicted in the clip. While the nursing student who did not partake in the scenario described the atmosphere as calm based on how the situation appeared on video, this characterization is treated as partial or even misleading, and, as an appearance, laughable (cf. Jefferson 1979), by the students who participated.

Not acknowledging the students’ laughter, the facilitator initiates a longer turn by asking the students what they “think about that” (line 312). As she continues the turn, it becomes clear that she provides a different take on the distinction between appearance and experience than the students who participated in the scenario: rather than treating the video as mere appearance, she contrasts the emotions previously described by the students with what actually can be seen in the video. While glancing down at her notes, she says that they are to “return to those feelings that you had” (line 312–313), referring to a point in the beginning of the debriefing when each of the students who had participated were asked to name one feeling that they had after the scenario. Afterwards, the facilitator produces a list of the reported feelings: “(ME1), you thought you were insufficient,” “(NU2), you said that you were unsecure,” and “(NU3), you were blocked.” This list is then used by the facilitator to provide a contrastive background to what then could be seen on the video. Whereas the feelings are tied to specific persons, the video is treated as a common point of reference to which all participants, regardless of whether they had participated in the scenario or not, have visual access: “‘n’ so we look at the clip” (line 316). In this sense, the appearance is given precedence over the described experiences: the students might have previously reported some negative feelings, but it is to the video that students should turn in answering the question about the atmosphere.

During the list construction, the facilitator shifts her gaze to the students about whom she is currently speaking. She then continues to hold her orientation towards the nursing student (NU3) who reported that he felt “blocked” after the scenario and who had not yet commented on the video clip. After a relatively long pause, and at a point where the nursing student who the facilitator has been looking at turns away from her and towards the screen, the nursing student who initially described the atmosphere takes the floor. Through her response, the student shows an understanding of the facilitator’s previous contributions as making a point; that the experiences reported by the students earlier were not visible in the displayed video clip: “it did not show on you.” After having received a confirmatory response from one of the students who participated in the scenario (line 320), the nursing student elaborates this point, saying that it was not “outwardly noticeable” and that she thinks a patient would have felt calm and safe in the present situation (lines 321–324). By raising the perspective of the patient, the appearance of calmness becomes something intrinsically valuable rather than something potentially deceiving; even though the students experienced feelings of insufficiency and insecurity, it was not outwardly noticeable and they were, therefore, able to attend to the patient in a professional way. Again, it is notable how students who have observed the performance of fellow students team up with the facilitator in attempts to reconceptualise the experiences expressed by those who participated in the scenarios – and how audiovisual appearances become a central resource in this project.

The facilitator acknowledges the nursing student’s contribution by nodding, but then immediately turns to the students who took part in the scenario, asking: “yeah how do you think (0.4) when you see this?” At this point, it is clear that the “you”/“ni” does not refer to the students in general, but to the students who took part in the scenario. While the two students that the facilitator is looking at turn their gazes down toward the table, the third student who took part in the scenario responds by first saying she does not think that the “sense is (.) like reflected in the clip” and subsequently, more in line with the nursing student who observed the performance, that it was not “outwardly vi:sible” (line 330). At this point, when one of the students who took part in the scenario explicitly acknowledged that the earlier reported feelings of insufficiency and insecurity were not seen in the recorded performance, the facilitator provides a strong confirmative response and subsequently moves on. Like in the previous fragment, it is here clear that the facilitator does not just pose a question in search of a correct answer or to test the student’s understanding as is common in traditional classroom instruction (cf. Mehan 1979). Instead, her questions are designed to make the students who participated in the scenario reconceive their performances based on how the situation appears audiovisually in the video. It is therefore not sufficient that a student who did not participate answers her question. Such responses might be useful in convincing the students who did participate to reconceive their performance, but it is not until there is some acceptance of a more positive view by a student who participated in the scenario that the sequence is closed.

Discussion

As pointed out in the introduction, several studies have shown that video can be used to facilitate feedback and promote reflection (cf. Fukkink et al. 2011, p. 56). In previous work, it has been argued that the use of video provides another perspective on the event, that it enables students to look at themselves from a distance, that it shows how the students have performed rather than how they think they have performed, and that it provides a more “objective” or “realistic” picture than what is provided by recollection (ibid.). This study investigates how additional perspectives are introduced in the debriefing and what objective or realistic might mean in terms of actual practice. The aim of the study has been to show, in interactional detail, how the students reflect on their collaborative work in the scenarios, and how this joint sense making is guided by the video and the contributions of both facilitators and fellow students. More specifically, the analysed fragments show how the video provides a third person perspective of the students’ own actions, and that recorded events can be used as evidence in convincing students to reconceive their understanding of individual and joint performances in the scenarios.

As have been repeatedly shown in the analysis section of this paper, the students talk about individual and collaborative actions in terms of appearances; for instance, by noting that they as individuals or as a group looked calm and attended to the patient in a professional way. Without the video, the students would not be able to talk about their performance in the scenario in this way; more specifically, they would not have the same access to a third-person perspective of their own conduct. One can further note how the students explicitly topicalise that the descriptions and assessments are based on a third-person perspective, as in “now when I watch here” (cf. Fragment 2). In this way, the third-person perspective provided by the video is implicitly contrasted with what they might have perceived, from a first-person perspective, in the actual situation. Although the students talk about their participation in terms of appearances, this does not mean that the perspective provided by the video cancels the relevancy of the other experiences that they have had. On the contrary, their participation in the scenario is regularly used as a background against which the appearances of the video are interpreted and understood. In the debriefings, and under the guidance of the facilitators, the students collaboratively compare and contrast their experiences of the scenarios with the additional perspective provided by the video. The debriefings thereby let the students practise skills in identifying and assessing effective teamwork, which are skills that are expected as the students enter medical practice.

There are several different takes on the relation between what is shown in the video and what the students experienced in and after the scenario. That they actually looked calm, despite feeling nervous, could be presented as a discovery, which they discovered by watching the video. It could also be presented as merely appearance, and as part of an argument that the video provides a limited, partial, or even misrepresentative view of the matter. Central here is how descriptions of appearances are tied to the assessment of student performance. To describe the atmosphere as calm provides another assessment of the situation instead of it being described as tense or panicky. As illustrated by the analyses, however, observation of the visible and audible conduct still leaves room for different evaluations. Even when there is agreement on what is shown in the video, there might be disagreements on how the visible performances of the students are to be assessed. Did the students fail in their performances because they were panicking, even though they appeared to be calm? Or did they succeed because they managed to uphold the appearance of being calm regardless of any experiences they might have had? While the scenarios are designed for practising collaboration and teamwork, the debriefings are exercises in identifying, understanding and assessing what good teamwork and professional collaboration might look like. It is possible that the whole discussion centred on the atmosphere and how the students appeared when working together might come across as a side-track, but against this one could argue that remaining calm and structured is central to the communication among team members and the performance of collaborative tasks. As one of the of the facilitators points out during a debriefing: it is okay to be nervous as long as these feelings do not “shine through” and affect the collaboration within the team.

Although video might be used to promote “self-reflection” and “self-assessment” in the debriefings, it is clear that this does not mean these reflections are to be done by the students themselves as isolated individuals. How the video-recorded performance is seen, reflected upon, and assessed is tied to the instructional and collaborative organization of the debriefings. With reference to the literature, the interaction could be characterized as “facilitated or guided reflection” (Fanning and Gaba 2007, p. 116). As illustrated by the three fragments, the design and sequential position of the questions make it relevant to answer in terms of what they see in the clip rather than what they experienced in the room. These instructional questions also project assessments as relevant next actions and, more specifically, as being made in positive terms; for instance, the questions request that the students describe “something that works well” (Fragment 1) and to contrast previously expressed negative experiences with the supposedly correct performances shown in the video (Fragments 2 and 3). In this context, to guide the students’ self-reflection centrally means to change their perception of their own teamwork and collaboration in the scenario. Rather than focusing on their mistakes, the students should learn to distinguish what characterizes well-functioning teamwork. The video is used as part of a particular instructional agenda, within which students who have participated in the scenarios and have expressed negative experiences are invited to reconceive their performance in a more positive light.

Collaboration and collaborative learning take on two quite distinct meanings here. On the one hand, how to collaborate in professional ways is what the students should learn from the scenarios, and collaboration or teamwork is also what the facilitators and students mainly discuss and what the video recordings show. On the other hand, the debriefings, although they are lead by facilitators, are performed collaboratively and aimed towards the joint analysis and sense making of the events shown in the recordings. Even though the centrality of instructional questions is shared with many other settings (e.g., Mehan 1979), the organizations of these debriefings are not identical to the organizations regularly found in classrooms where teachers ask questions and students provide answers. In the debriefings, students might join the facilitators in convincing fellow students to reconceptualise their understanding of their performance. Sometimes when students express dissatisfaction with how they acted and communicated in the scenarios, other students respond by highlighting the positive aspects that are shown in the video. In doing this, however, they do not position themselves as more knowledgeable about teamwork than their fellow students. Instead, they rely on the audiovisual features of the recordings in making their arguments.

Although debriefing has been described as the “heart and soul” of simulator training and as crucial for the participants’ learning, little attention has been paid to the professional issues that are topicalized during the debriefings and how these issues are raised and handled. The results of this study show that many goals of interprofessional teamwork are addressed in the participants’ interactions, such as collaborating in a calm and structured manner, being attentive to what other team-members do and say, delivering concise and structured handover-reports, and maintaining a well-organized collaboration. In accordance with previous research (e.g., Borko et al. 2011; Erickson 2007; Lindwall et al. 2014), however, the study also shows that the instructional use of video does not guarantee that inexperienced participants themselves discern professionally relevant aspects. This study attempts to show how instructors guide the students to see the recorded events in a particular way that is relevant for the professions; or, as Goodwin (1994) states in his seminal study of expert witnesses, how they organize “the perceptual field provided by the videotape into a salient figure” (p. 620). In line with Goodwin’s study, McIlvenny (2011) demonstrates the power of using video to convince a reluctant audience (something that parallels the setting investigated here) by having the instructor, together with peer-students, reconceptualise situations by highlighting specific occurrences in the video (cf. Fragment 3).

Therefore, the video is central, but it does not itself guarantee success. The students recurrently take their own appearances as a starting point for their comments (cf. Fragment 2), which seems to distract their attention from the instructional agenda: to focus on professionally relevant aspects of teamwork. In line with Fukkink et al. (2011), the results of this study show that unguided seeing could lead to a focus on superficial impressions and could require instructional efforts that redirect the participants’ attention to substantial aspects. Without further guidance, novices might “find themselves at sea, in a stream of continuous detail they don’t know how to parse during the course of their real-time viewing in order to make sense of it” (Erickson 2007, p. 146). In summary, the video provides a resource for observing one’s own actions and interactions with others from a third-person perspective. The video is used to reactualise prior events, but, in addition, the third-person perspective of the video is used to reconceptualise how the participants’ performances are to be seen and assessed. The video recordings become central resources in guiding students’ focus, and the distinction between experiences and appearances is made relevant in terms of professional conduct.

Notes

“Interprofessional team work” means that members from two or more professions work together and contribute with their skills and strengths, respectively. The goal of interprofessional training is for the members to develop knowledge and understanding of the other participating professions.

SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) is a model for communication that is used to ensure efficient transmission of information in, for instance, handover reports. Speak-up and closed loop communication are techniques for effective communication included in the CRM (Crew Resource Management) concept, which is a set of principles that are intended to help prevent difficulties and errors related to teamwork and communication. Speak-up means for all team members to raise their voices and inform the other team members if they notice some issue/s that might be of importance for the patient’s well being. Closed loop communication means communication with feedback, that is, for the team members to confirm that they have heard and understood what other team members say.

The student performed the first step in an SBAR-report, that is, a brief report of the current situation.

The Swedish term “känsla” is here translated to “sense”, although it literally is closer to “feeling”.

In the debriefings, the facilitators sometimes characterize these as the “hot seat” participants.

References

Beckman, H. B., & Frankel, R. M. (1994). The use of videotape in internal medicine training. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 9(9), 517–521.

Borko, H., Koellner, K., Jacobs, J., & Seago, N. (2011). Using video representations of teaching in practice-based professional development programs. ZDM Mathematics Education, 43(1), 175–187.

Broth, M., Laurier, E., & Mondada, L. (2014a). Introducing video at work. In M. Broth, E. Laurier, & L. Mondada (Eds.), Studies of video practices: Video at work (pp. 1–29). London: Routledge.

Broth, M., Laurier, E., & Mondada, L. (Eds.). (2014b). Studies of video practices: Video at work. London: Routledge.

Byrne, A. J., Sellen, A. J., Jones, J. G., Aitkenhead, A. R., Hussain, S., Gilder, F., Smith, H. L., & Ribes, P. (2002). Effect on videotape feedback on anaesthetists’ performance while managing simulated anaesthetic crises: A multicentre study. Anaesthesia, 57(2), 169–182.

Derry, S. J., Siegel, M., & Stampen, J. (2002). The STEP system for collaborative case-based teacher education: Design, evaluation & future directions. In G. Stahl (Ed.), Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Support for Collaborative Learning: Foundations for a CSCL Community (pp. 209-216). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Erickson, F. (2007). Ways of seeing video: Towards a phenomenology of viewing minimally edited footage. In R. Goldman, R. Pea, S. Barron, & S. Derry (Eds.), Video research in the learning sciences (pp. 145–155). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associate Publishers.

Fanning, R. M., & Gaba, D. M. (2007). The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simulation in Healthcare, 2(2), 115–125.

Farquharson, A. L., Cresswell, A. C., Beard, J. D., & Chan, P. (2013). Randomized trial of the effect of video feedback on the acquisition of surgical skills. British Journal of Surgery, 100(11), 1448–1453.

Flin, R., Glavin, R., Maran, N., & Patey, R. (2003). Anaesthetists’ non-technical skills (ANTS) system handbook v1. 0. Aberdeen, UK: University of Aberdeen.

Fukkink, R. G., Trienekens, N., & Kramer, L. J. C. (2011). Video feedback in education and training: Putting learning in the picture. Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 45–63.

Fuller, F. F., & Manning, B. A. (1973). Self-confrontation reviewed: A conceptualization for video playback in teacher education. Review of Educational Research, 43(4), 469–528.

Glenn, P. (2003). Laughter in interaction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633.

Grant, J. S., Moss, J., Epps, C., & Watts, P. (2010). Using video-facilitated feedback to improve student performance following high fidelity simulation. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 6(5), 177–184.

Greiffenhagen, C. (2012). Making rounds: The routine work of the teacher during collaborative learning with computers. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(1), 11–42.

Haggerty, G., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2011). The use of video in psychotherapy supervision. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 27(2), 193–210.

Hamilton, N. A., Kieninger, A. N., Woodhouse, J., Freeman, B. D., Murray, D., & Klingensmith, M. E. (2011). Video review using a reliable evaluation metric improves team function in high-fidelity simulated trauma resuscitation. Journal of Surgical Education, 69(3), 428–431.

Heritage, J., & Atkinson, J. M. (Eds.). (1984). Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hindmarsh, J., & Heath, C. (2007). Video-based studies of work practice. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 156–173.

Jefferson, G. (1979). A technique for inviting laughter and its subsequent acceptance/declination. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology (pp. 79-96). New York: Halsted (Irvington).

Jefferson, G. (1984). Transcript notation. In M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. ix–xvi). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kong, S. C., Shroff, R. H., & Hung, H. K. (2009). A web enabled video system for self reflection by student teachers using a guiding framework. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 25(4), 544–558.

Koschmann, T. (2013). Conversation analysis and collaborative learning. In C. E. Hmelo-Silver, C. Chinn, C. K. K. Chan, & A. O’Donnell (Eds.), The international handbook of collaborative learning (pp. 149–167). New York: Routledge.

Koshik, I. (2002). A conversation analytic study of yes/no questions which convey reversed polarity assertions. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(12), 1851–1877.

Kurtz, S. M., Silverman, J., & Draper, J. (2005). Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine. Oxford: Radcliffe publishing.

Lederman, L. C. (1992). Debriefing: Toward a systematic assessment of theory and practice. Simulation & Gaming, 23(2), 145–160.

Lerner, G. H. (2003). Selecting next speaker: The context-sensitive operation of a context-free organization. Language in Society, 32(02), 177–201.

Lindwall, O., Johansson, E., Ivarsson, J., Rystedt, H., & Reit, C. (2014). The use of video in dental education: Clinical reality addressed as practical matters of production, interpretation, and instruction. In M. Broth, E. Laurier, & L. Mondada (Eds.), Studies of video practices: Video at work (pp. 161–180). Abingdon: Routledge.

Lymer, G., Ivarsson, J., & Lindwall, O. (2009). Contrasting the use of tools for presentation and critique: Some cases from architectural education. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4(4), 423–444.

McIlvenny, P. (2011). Video interventions in “everyday life”: Semiotic and spatial practices of embedded video as a therapeutic tool in reality TV parenting programmes. Social Semiotics, 21(2), 259–288.

Mehan, H. (1979). “What time is it, Denise?”: Asking known information questions in classroom discourse. Theory Into Practice, 18(4), 285–294.

O'Donoghue, P. (2006). The use of feedback videos in sport. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 6(2), 1–14.

Payne, G. C., & Hustler, D. (1980). Teaching the class: The practical management of a cohort. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 1(1), 49–66.

Rystedt, H., Reit, C., Johansson, E., & Lindwall, O. (2013). Seeing through the dentist’s eyes: Video-based clinical demonstrations in preclinical dental training. Journal of Dental Education, 77(12), 1629–1638.

Sacks, H. (1984). Notes on methodology. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 21–27). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735.

Stahl, G. (2012). Ethnomethodologically informed. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(1), 1–10.

Steinwachs, B. (1992). How to facilitate a debriefing. Simulation & Gaming, 23(2), 186–195.

Tripp, T. R., & Rich, P. J. (2012). Using video to analyze one’s own teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(4), 678–704.

van Es, E. A. (2009). Participants' roles in the context of a video club. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 18(1), 100–137.

Zahn, C., Krauskopf, K., Hesse, F. W., & Pea, R. (2012). How to improve collaborative learning with video tools in the classroom? Social vs. cognitive guidance for student teams. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(2), 259–284.

Zottmann, J. M., Goeze, A., Frank, C., Zentner, U., Fischer, F., & Schrader, J. (2012). Fostering the analytical competency of pre-service teachers in a computer-supported case-based learning environment: A matter of perspective? Interactive Learning Environments, 20(6), 513–532.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Johansson, E., Lindwall, O. & Rystedt, H. Experiences, appearances, and interprofessional training: The instructional use of video in post-simulation debriefings. Intern. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn 12, 91–112 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-017-9252-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-017-9252-z