Abstract

According to the factualist interpretation, the skeptical solution to the skeptic’s problem hinges on rejecting inflationary accounts of semantic facts, advocating instead for the adoption of minimal factualism. However, according to Alexander Miller, this account is unsound. Miller argues that minimal factualism represents a form of semantic primitivism, a position expressly rejected by Kripke’s Wittgenstein. Furthermore, Miller states that minimal factualism presupposes the conformity of meaning ascriptions with rules of discipline and syntax. However, he contends that this maneuver is also undermined by Kripke’s skepticism. In this paper, I demonstrate that Miller’s arguments against minimal factualism are unsound. To achieve this goal, I argue that the minimalist account of semantic facts should not be equated with semantic primitivism. Moreover, I argue that statements regarding the conformity of meaning ascriptions are either beside the criticism of Kripke’s skeptic or should be interpreted from the perspective of the account on assertibility offered by the skeptical solution. On this basis, I conclude that the factualist interpretation provides a conducive environment for solving the problem posed by Kripke’s skeptic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In „Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language,” Kripke (1982) presents his interpretation of Wittgenstein’s remarks regarding rule-following. The climax of Kripke’s interpretation is the skeptical problem, which revolves around the question of whether there are any semantic facts that determine what an agent means by a given expression. Kripke introduces the figure of the skeptic, who claims that there are no such facts. Based on this claim, the skeptic nihilistically concludes that all our meaning ascriptions are systematically in error, which is tantamount to stating that there can be no such thing as meaning anything by any word. According to Kripke, Wittgenstein provides a skeptical solution to the problematic conclusion of the skeptic. Wittgenstein agrees with the skeptic that there are no semantic facts in neither the „internal” nor the „external” world (Kripke, 1982, p. 69). Nevertheless, Wittgenstein rejects the nihilistic conclusion the skeptic derives from this state of affairs. He argues that our ordinary practice of ascribing meaning does not require the kind of justification that the skeptic has demonstrated to be untenable (Kripke, 1982, p. 66).

For decades, one of the most popular ideas in the literature was that the skeptical solution offers a non-factualist position on meaning-ascription (Wright, 1984; Boghossian, 1990). This position agrees with the skeptic that there are no semantic facts of any type. However, it suggests that the skeptical solution avoids semantic nihilism by stating that meaning ascriptions have no truth-conditions, as the function of meaning ascriptions is expressive rather than descriptive. Nevertheless, a closer look at the literature reveals that the non-factualist interpretation suffers from certain weaknesses. The foremost problems of the non-factualist interpretation were indicated by Wright (1984), Boghossian (1990), Kusch (2006), Hattiangadi (2007), and Miller (2011).

Several authors have tried to defend the non-factualist interpretation by responding to the problems mentioned above (Boyd, 2017; Guardo, 2020; Miller, 2020). Other scholars, on the other hand, have dealt with the problems of the non-factualist interpretation by adopting the factualist stance toward the skeptical solution. According to proponents of the factualist interpretation, meaning ascriptions do have a descriptive function. Accordingly, in order to answer the problem posed by the skeptic, they argue that the most crucial idea of the skeptical solution is the rejection of not so much the semantic facts as their particular explanatory capacity.

Over time, extensive literature has developed on the factualist position. Consequently, two factualist ways of interpreting the skeptical solution arose – factualism without minimalism and factualism via minimalism. In order to answer the problem posed by the skeptic, the first one relies on the remarks Kripke’s Wittgenstein makes about assertibility conditions in Chap. 3 of Kripke (1982). According to this approach, the assertibility of meaning ascriptions is not governed by a property or set of properties serving as its pre-established standard of correctness. Rather, it explains the assertibility of meaning ascriptions in virtue of the facts about the overall linguistic use of the terms that the ascriptions correctly describe. This way of understanding the factualist interpretation was established, for instance, in Byrne (1996) and Wilson (1994, 1998).

In turn, the „minimalist” reading of the Skeptical Solution answers the skeptic’s problem in terms of a deflationary account of facts and truth. According to this view, meaning ascriptions are truth-apt because they satisfy two conditions relating to discipline and syntax. Consequently, it suggests that meaning ascriptions have only deflationary truth conditions. Nevertheless, in virtue of these conditions, one may attribute meaning ascriptions with descriptive semantic function. On this basis, the advocates of minimal factualism state that the explanation of the truth of meaning ascriptions does not involve any facts. Nonetheless, they argue that the existence of semantic facts follows from the idea that when „Jones means addition by ‘+’„ is true, then one may trivially affirm that there is a fact that Jones means addition by ‘+’. It is worth noting that the minimalist approach seems to be advocated by the majority of „factualist” interpreters of the skeptical solution. It is explicitly endorsed by Davies (1998, p. 131), Wilson (2003, p. 180), Kusch (2006, p. 172) and Šumonja (2021, p. 15). For this reason, this paper considers only the minimalist version of the factualist interpretation.

Although minimal factualism appears to avoid the problems of the non-factualist account, Miller (2010) offers two arguments against this position. Firstly, he states that it falls into a form of semantic primitivism, a position rejected explicitly by Kripke’s Wittgenstein. Consequently, Miller (2010, p. 181) concludes that this type of factualist interpretation is an implausible reading of the skeptical solution. Secondly, Miller argues that the minimalist interpretation depends on the conformity of meaning ascriptions to rules of discipline and syntax – although the plausibility of this maneuver is undermined by Kripke’s skeptic.

Therefore, given that we are in trouble to point out at least one interpretation of it that does not collapse under the weight of criticism, the question then becomes whether the skeptical solution remains a credible position. The overall goal of this paper is to address this problem, by refuting Miller’s arguments against the minimalist interpretation.

To refute Miller’s objection, I will demonstrate that there is no reason to believe that semantic minimalism, as endorsed by the factualist interpretation, fits within the scope of semantic primitivism. In this regard, I will refer to the distinction between sparse and abundant properties, as well as the discussion on the closure principle initiated in the field of epistemology, which concerns whether knowledge is closed under known entailment. Based on this, I will argue that semantic primitivism suggests the sparseness of semantic facts, whereas the skeptical solution, by rejecting the idea that the assertibility of meaning ascriptions is closed under assertible implication, implies that semantic facts are abundant. Further, I will establish that the factualist interpretation is invulnerable to the objections formulated by the skeptic against semantic primitivism as well. Moreover, I will argue that the notion of conformity to rules of discipline and syntax is compatible with the skeptical solution.

It is noteworthy that an inherent limitation of this paper is its omission of promoting the factualist interpretation as the most appropriate account of the skeptical solution over other positions that characterize the skeptical solution as a form of expressivism (Miller, 2020) or meaning relativism (Guardo, 2020). Instead, this study modestly illustrates that minimal factualism guarantees that there is at least one plausible interpretation of the skeptical solution that withstands criticism.

The discussion in this text proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2, I lay out Miller’s objections to minimal factualism as an interpretation of the skeptical solution. In Sect. 3, I address the question of whether semantic minimalism, as endorsed by the factualist interpretation, aligns with the scope of semantic primitivism. In Sect. 3.1 I pinpoint crucial distinctions between the primitivist and minimalist positions. In Sect. 3.2, I reconstruct Kripke’s critique of semantic primitivism and establish that this critique does not apply to the type of semantic minimalism endorsed by the factualist interpretation. The purpose of the following sections is to illustrate that the form of semantic minimalism endorsed by the factualist interpretation – in contrast to Miller’s objection – provides a plausible interpretation of the skeptical solution to the skeptical problem. In Sect. 4.1, I identify a key element of the skeptical solution, which is the rejection of the closure principle of assertibility of meaning ascriptions. In Sect. 4.2, I argue that the closure principle can be refuted on the basis of the factualist interpretation, but not on the basis of semantic primitivism, which opposes the identification of these two positions. In Sect. 5, I refute Miller’s argument that the minimalist interpretation relies on the conformity of meaning ascriptions to rules of discipline and syntax – a possibility that is undermined by Kripke’s skeptic.

2 Miller’s Critique of the Factualist Interpretation of the Skeptical Solution

According to Miller (2010, p. 180), one reason why the factualist interpretation of the skeptical solution should be rejected is that it is a form of semantic primitivism, an account that Kripke’s Wittgenstein openly rejects (1982, pp. 51–53). Miller reaches this conclusion by noting that the factualist account of meaning ascriptions tends to rely on the minimalist account of truth-aptitude. Miller refers here to the proposal of Wright (1992), according to whom the sentences of a given region of discourse are truth-apt—and thus potentially descriptive—if they meet the following two conditions: (1) discipline, necessitating acknowledged standards for the proper and improper use of sentences of the discourse, and (2) syntax, such that the sentences of the discourse must possess the right syntactic features, e.g., they must be capable of conditionalization, negation, embedding in propositional attitudes, etc. Miller concurs that, according to the minimal factualist, meaning ascriptions satisfy both these conditions (Miller, 2010, p. 180), rendering them truth-apt, and – given the idea that on the basis that sentence “p” is true, then one may trivially affirm that there is a fact that p – descriptive of factual matters.

Miller posits two arguments against the factualist interpretation of the skeptical solution. Firstly, he contends that integrating the factualist account of meaning ascriptions within the minimalist account of truth-aptitude blurs the distinction between the former and the account endorsing that meaning is a primitive and sui generis psychological state – an account that, as Miller (2010, pp. 180–181) notes, Kripke’s Wittgenstein rejects as mysterious and desperate. Miller argues that this conflation is sufficient to deem the factualist interpretation of the skeptical solution fundamentally flawed and should not be attributed to Kripke’s Wittgenstein (Miller, 2010, p. 181). I will refer to this claim as “the identification argument”. Secondly, Miller contends that attributing truth conditions to meaning ascriptions via minimal truth-aptitude needs to take for granted the notion of conformity to a rule, as it is based on the condition of discipline and the condition of syntax, which presumably rely on the concept of a rule. However, taking for granted the idea of conformity to a rule constitutes a commitment explicitly rejected by the Skeptic. This argument is labeled the Granted Rule Argument.

3 Response to the Identification Argument

In this section, I am going to refute Miller’s identification argument against the factualist interpretation of the skeptical solution by demonstrating that it is based on the mistaken association of a minimalist conception of meaning and semantic primitivism. To achieve this aim, I will first elaborate on the difference between primitivist and minimalist perspectives on meaning. Subsequently, I will clarify why semantic minimalism remains beyond the scope of the skeptic’s objection against the primitivist position.

3.1 Semantic Primitivism and Semantic Minimalism

To confirm that minimalism is not in the scope of the skeptical critique of the primitivist account of meaning, it is necessary to identify what distinguishes these two positions. In this regard, I will analyze how the boundary between these positions is drawn in discussions concerning the property of truth, and then I will elaborate on its consequences for semantic facts.

Primitivists tend to characterize the property of truth as something substantial that, despite its inexplicability, remains a „sparse” property. In turn, on the deflationary account, the truth property is considered as something abundant (Edwards, 2013, p. 280). Asay elaborates on this distinction by referring to the ideas of Goodman (1983). Suppose there are two sparse properties – green and blue – that correspond to universals. Meanwhile, the properties grue and bleen, by contrast, are abundant properties that correspond to no universals. Thus, we would not consider grue and bleen sparse, because they are not basic, for they reduce to green and blue, which are basic (Asay, 2013, p. 30).

Douglas Edwards addresses this concern, indicating that a property of truth is substantial (or ‘sparse,’ as he terms it) if it possesses proper metaphysical weight. For instance, if truth is reasonably sparse, then truths form a genuine kind, and they share a property in virtue of which they are truths. Furthermore, substantial properties ground genuine similarities between entities of a given kind and feature in causal-explanatory relations (Edwards, 2013, p. 291). On the other hand, non-substantive properties don’t form any genuine kind, don’t play any causal-explanatory role, don’t carry any metaphysical weight, and essentially there is very little to say about them (Edwards, 2013, p. 292).

In this regard, primitivists argue that the property of truth is metaphysically basic, akin to how we might consider an electric charge in physics (Asay, 2021, p. 526). As such, truth-bearers are true by virtue of possessing this fundamental property of truth. One of the earliest advocates of the primitivism about truth was Moore, who presented his argument as follows:

The difference between a true and a false belief (…) consists simply in this, that where the belief is true the proposition, which is believed, besides the fact that it is or “has being’” also has another simple unanalyzable property which is possessed by some propositions and not by others. The propositions which don’t possess it, and which therefore we call false, are or “have being’” just as much as those which do; only they just have not got this additional property of being “true.” (Moore, 1953, p. 261).

According to Moore, truth is a certain “simple unanalyzable property”, the possession of which separates true from false beliefs. It is worth noting that primitivism argues not that we have yet to identify what constitutes the truth; rather, it asserts that looking for what might constitute the truth is the incorrect approach. Such a theory of truth cannot exist, as the properties to which it would refer are fundamental to thought and language (Edwards, 2013, p. 287).

In turn, deflationism has been defined as a theory that simply denies the existence of a property like ‘being true’ (see for example Strawson, 1950). However, it became evident that such a stance led to unsatisfactory inconsistencies (see e.g. Boghossian, 1990, p. 175), prompting many deflationists to acknowledge the existence of properties such as ‘being true,’ albeit in a minimal sense (see Horwich, 1998). Now, the question that arises is: what distinguishes the deflationist account of properties from inflationist theories? As Krzysztof Posłajko notes, in addressing this question, deflationists point out that although terms like ‘truth’ denote a property, the property in question is not substantive (Posłajko, 2017, p. 47). Yet, this idea compels deflationists to propose a criterion for distinguishing between substantive and non-substantive properties.

To apply the above considerations to the debate on the nature of semantic facts, we can say that semantic facts, according to the primitivists, are certain sparse entities, whereas, according to semantic minimalism, they are something abundant. Consequently, in the primitivist view, the fact that an agent means addition by the symbol “+” plays a particular explanatory role in her use of “+”, and it exemplifies a form similar to, for example, the fact that she means subtraction by the symbol “-.” Meanwhile, based on minimalism, semantic facts do not exemplify any genuine type, nor do they play any particular explanatory role toward agents’ use of the symbols “+” or “-.”

3.2 Kripke’s Critique of the Semantic Primitivism

In this section, I will present the critique that Kripke’s skeptic formulated against semantic primitivism. Kripke himself paid little attention to this position: his skeptic considered whether it could be argued that conveying the concept of addition using the symbol „+” is a certain sui generis primitive state, but he rejects this idea quite quickly, arguing that this move appears to be an act of desperation (Kripke, 1982, p. 51). Kripke presents two objections to this concept. First, he suggests that, based on semantic primitivism, the nature of the state of meaning something by a given expression is completely mysterious, and it is unclear how this fact determines whether, for example, Jones, by using the symbol „+”, means addition rather than quaddition.

However, the mysteriousness of the primitivist account of meaning is not the only problem identified by Kripke. His second objection to primitivism relies on a claim that the state of meaning something by a given expression, based on the primitivists’ viewpoint, appears logically impossible (or at least logically problematic), as such a state must be constituted by an infinite object contained in our finite minds. However, this state cannot persist by thinking explicitly about each case of, for example, the addition table, nor can encoding every separate case in the brain, as we lack the capacity for it. Yet, primitivists seem to argue that „in a queer way,” each such case is already „in some sense present,” an idea that Kripke questions, as he believes there is no reason to avoid interpreting this finite state in a quus-like way (Kripke, 1982, p. 52).

In my opinion, the main issue raised by Kripke’s objection concerns the primitivists’ attribution of the causal-explanatory role to semantic facts. According to the primitivists, each case is already „in some sense present” in a state of meaning something by a given expression. However, if each case already exists in such a state, then this state can be considered a kind of “conclusive reason” for applying a given expression in given circumstances: if each case is already „in some sense present,” by meaning addition using the symbol „+” and acting in accordance with this state, I would have to answer unambiguously the question concerning a sum of arbitrarily large numbers. Thus, it seems that according to primitivists, the state of meaning something by a given expression cannot be explained in other terms, but it still plays a causal-explanatory role in that agents use a given expression in a particular way. Furthermore, Kripke, by explaining the reason to interpret this state of meaning something, as it is viewed by primitivists, for example, in a quus-like way, seems to suggest that such a state cannot function in such a role.

Therefore, the scope of skeptical challenges is confined to the implications of semantic primitivism that endorse the perspective of semantic facts as being limited. Conversely, the factualist interpretation of the skeptical solution suggests that semantic facts are notably prevalent, leading to the conclusion that the critique against the factualist approach mistakenly conflates the minimalist understanding of meaning with a specific type of semantic primitivism. Consequently, the argument that factualist interpretation and semantic minimalism are susceptible to skepticism directed at semantic primitivism lacks validity.

Considering the points raised, I posit that skeptical objections to semantic primitivism specifically target the primitivist notion that semantic facts play a certain causal-explanatory role in how an agent uses a given expression. Conversely, the factualist interpretation of the skeptical solution suggests that semantic facts are notably abundant, leading to the conclusion that Miller’s critique against the factualist approach mistakenly conflates the minimalist conception of meaning with a certain form of semantic primitivism.

4 Factualist Interpretation and the Skeptical Solution

In the preceding section, I argued that minimal factualism remains resilient to the skeptic’s critique of semantic primitivism. In this section, I will elaborate on how the notion of the abundant semantic facts contributes to addressing the skeptic’s problem. In this regard, I will establish one of the key elements of the skeptical solution – rejecting the closure principle of assertibility of meaning ascriptions – requires the rejection of the substantial role of semantic facts.

The closure principle entails that the assertibility of a given meaning ascription, such as “Jones means addition by ‘+’”, requires the rejection of alternative meaning ascriptions, such as “Jones means quaddition by “+’”. Accordingly, the rejection of the closure principle for assertibility conditions entails that “Jones means addition by the symbol ‘+’” may be assertible, despite the fact that by “+” Jones might mean quaddition as well. Thereafter, I will refute Miller’s identification argument, by showing that the rejection of the closure principle is feasible on the grounds of the abundant view of semantic facts, as endorsed by the factualist interpretation, while it is not feasible on the grounds of the sparse view of semantic facts, as endorsed by semantic primitivists.

4.1 Closure Principle and the Skeptical Solution

The discussion of the closure principle was initiated in the field of epistemology in the context of the problem of knowledge attribution. In this regard, the closure principle states that if you know that P is true and you know that the truth of P implies the truth of Q, then you know that Q is true (Dretske, 2005, p. 27). However, Dretske notes that the principle under discussion has problematic consequences because its contraposition entails that if you know that P implies Q, but you do not know that Q is true, then you do not know whether P is true (Dretske, 2005, p. 31). Dretske illustrates this as follows:

If looking at an animal in a zoo, I might therefore think it is a zebra. Suppose that I know that if an animal is a zebra, it is not another animal, such as a cleverly painted mule meant to pretend to be a zebra. It follows from the principle of closure that if I do not know that the animal I am looking at is not a very cleverly painted mule, then I do not know that it is a zebra. (Dretske, 1970, p. 1116)

Thus, given that all evidence to which I have access justifies both the claim that the animal is a zebra and the claim that it is a painted mule, the closure principle entails that I do not know that the animal at which I am looking is a zebra.

Rejection of the closure principle in the context of knowledge attribution is one of the primary components of Dretske’s Relevant Alternatives Theory (RAT), which argues against the closure principle as follows:

Looking at a zebra at the zoo, I know it is a zebra. Even if I have no evidence against the thesis that the animal I am looking at is not a skillfully painted mule (since my visual experience is compatible with this possibility as well) and I know that if something is a zebra, it is not a painted mule, I can still know that the animal I am looking at is a zebra. I don’t have to rule out the fact that it is a skillfully painted mule, because, on a typical visit to the zoo, the judgment that what I am looking at is a skillfully painted mule is not a relevant alternative to the judgment that it is a zebra (Dretske, 2005, p. 33).

Thus, RAT states that knowing that a judgment J is true requires the ability to exclude not all but only relevant alternatives to J.

I argue that the problem of assertibility of meaning-ascriptions posed by the skeptic is similar to the problem of knowledge raised by Dretske, as it presupposes a certain form of a closure principle:

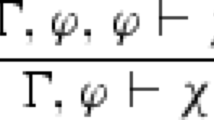

(A-Closure Principle). Assertibility of meaning ascriptions is closed under assertible implication.

Therefore, according to the A-Closure Principle,

-

(1)

“Jones means addition by ‘+’” is assertible.

-

(2)

“Jones means addition by ‘+’ → Jones does not mean quaddition by ‘+’” is assertible.

-

(3)

“Jones does not mean quaddition by ‘+’” is assertible.

is a valid argument.

Nevertheless, the skeptic focuses on a transposition of the above reasoning,

Because, on the basis of the A-Closure Principle,

-

(1)

“Jones means addition by ‘+’ → Jones does not mean quaddition by ‘+’” is assertible.

-

(2)

“Jones does not mean quaddition by ‘+’” is not assertible

-

(3)

“Jones means addition by ‘+’” is not assertible.

is a valid argument as well.

On this basis, the skeptic argues that I cannot assert that Jones means addition by ‘+’, because I am not in a position to assert that Jones does not mean quaddition by ‘+’, since all the available facts about Jones support both claims – “Jones means addition by ‘+’” and “Jones means quaddition by ‘+’”. In other words, I cannot assert that Jones means addition by ‘+’, as there are no facts to exclude the possibility that he means quaddition by ‘+’ (Kripke, 1982, p. 23).

The resemblance between Dretske’s thought experiment with the zoo and the skeptic’s argument concerning quaddition sheds light on the fact that the skeptical problem presupposes the A-Closure Principle. More crucially, this analogy deepens our understanding of the skeptical solution. In this regard, it is noteworthy that Dretske admits that there is no fact that an animal I am looking at is a zebra rather than a skillfully painted mule, suggesting that knowledge attribution does not require such facts. Similarly, Kripke states that “we must give up the attempt to find any fact about me in virtue of which I mean ‘plus’ rather than ‘quus’, and must then go on in a certain way” (Kripke, 1982, p. 108), suggesting that even if there is no fact that by “+” Jones means addition rather than quaddition, it does not undermine the assertibility of meaning ascriptions. In other words, a given agent may assert that Jones means addition by ‘+’, even if she is not in a position to assert the implication of this statement, that is, that Jones does not mean quaddition by ‘+’. It is noteworthy that the fact that meaning ascriptions do not require such facts can be explained in several ways. For example, one may offer a non-cognitivist explanation of meaning ascriptions, arguing that we do not need any fact in virtue of which I mean ‘plus’ rather than ‘quus’, because meaning ascriptions express desire-like, conative states. This would imply that there is no incompatibility between “Jones means addition by ‘+’” and “Jones means quaddition by ‘+’”, as these sentences do not express any propositions that could be incompatible. Nonetheless, I do not believe this to be the case; and if so, then a rejection of the assumption that assertibility of meaning ascriptions is closed under assertible implication provides the simplest explanation for the assertibility of meaning ascriptions.

It’s worth noting that, according to Dretske, our knowledge of a particular statement hinges on our ability to exclude relevant alternatives to this statement. Similarly, the assertibility of particular meaning ascription hinges on our ability to exclude relevant alternatives to this ascription. Therefore, in order to assert that Jones means addition by ‘+’, I don’t have to be able to exclude a skeptical claim that Jones means quaddition by ‘+’, because the skeptical alternative is not a relevant alternative to our claim. However, this solution may not be feasible, as we cannot dismiss the skeptic’s claim that her alternative is indeed relevant. But if this is indeed the case, then, to assert that Jones means addition by ‘+’, I supposedly need to be able to exclude the claim that he means quaddition by ‘+’. Since I lack this ability, because internal and external facts concerning Jones do not definitively determine whether he means addition or quaddition by ‘+’, I must concede that I cannot assert that Jones means addition by ‘+’. In order to answer the above issue, I argue that the skeptical solution may be seen as a view that the assertibility of a particular meaning ascription depends not on our ability to exclude relevant alternatives, but rather on our ability to exclude alternatives that are worse than ours. Therefore, a particular meaning ascription is assertible iff it is not worse than its alternatives; it is not assertible, iff it is worse than its alternatives. This viewpoint renders the sentence “Jones means addition by ‘+’” assertible, even if, based on all possible facts, we cannot deny that Jones means quaddition by ‘+’.

4.2 Semantic Facts and the Closure Principle

In the previous section, I discussed the rejection of the closure principle as the crucial idea of the skeptical solution and its efficiency in resolving the skeptical problem. In this section, I will elaborate on why this approach is not viable under the framework of semantic primitivism, while it still applies within the context of minimal factualism.

If the fact that Jones means addition by „+” is a „sparse” fact, then there is an element of reality that plays a causal-explanatory role and provides clearly defined outcomes in Jones’ usage of “+”. As Kripke notes, such a fact should „entail that, if I wish to accord with it, and remember the state, and do not miscalculate, I must give a determinate answer to an arbitrarily large addition problem” (Kripke, 1982, p. 53). Consequently, such a fact should simultaneously determine the truth of the statement “Jones means addition by ‘+’” while establishing the falsehood of all meaning ascriptions that are incompatible with it.

On the other hand, the rejection of the closure principle makes the assertibility of two incompatible meaning ascriptions possible, rendering both the assertibility of the statement “Jones means addition by ‘+’” and the statement “Jones means quaddition by ‘+’”. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that on the basis of the deflationist stance toward truth, it implies the truth of both these statements as well. Consequently, given the idea that when „Jones means addition by ‘+’„ is true, then one may trivially affirm that there is a fact that Jones means addition by ‘+’, the rejection of the closure principle results in the internal inconsistency of the state of meaning something. Such a fact of meaning something does not provide sufficient reasons for an agent to give an unequivocally definite answer to equations involving the sum of arbitrarily large numbers. In other words, despite the assertibility of the statement that Jones means addition by „+”, Jones still may provide one of two conflicting answers to the equation „67 + 58.” On this basis, it may be concluded that the fact of meaning something does not play a significant causal-explanatory role in Jones’ usage of „+.” All these observations emphasize the abundance of the fact of meaning something rather than its sparseness. For this reason, I believe, the account of the state of meaning something derived from the rejection of the closure principle of assertibility of meaning ascriptions cannot be equated with semantic primitivism.

It is noteworthy that, for the same reason, the rejection of the closure principle aligns with the minimalist account of semantic facts. A minimalist factualist is not committed to stating that an agent, based on what she means, should yield a specific answer (such as this rather than that) to the equation “58 + 67.” In other words, minimalist semantic facts, derived from particular meaning ascriptions, do not play any significant role in excluding meaning ascriptions alternative towards the original one. Therefore, the minimal factualist is not troubled by the outcome of rejecting the closure principle, wherein the sentence “Jones means addition by ‘+’” is assertible, even without reasons to deny the possibility that Jones means quaddition by “+.” Consequently, the rejection of the closure principle poses no concern for the advocates of minimal factualism.

5 Response to the Granted Rule Argument

In response to the Granted Rule Argument, we shall turn to Immanuel Kant’s distinction between actions that conform to a rule and actions that follow a rule. According to Kant, the evaluation of an action’s conformity or non-conformity with a rule is independent of whether the rule was an incentive for the action. On the other hand, the determination of whether a particular agent follows a rule by his action examines whether the rule is the incentive for the action. Hence, we can construe Miller’s argument in two distinct ways:

-

(1)

there is no fact that a given meaning ascription made by an agent S conforms to particular discipline and syntax rules.

-

(2)

there is no fact that an agent S, while attributing truth conditions in virtue of a deflationary account about truth-aptness, follows particular discipline and syntax rules.

On the basis of the first interpretation, Miller argues that attributing deflationary truth conditions to meaning-ascriptions requires the conformity of meaning ascriptions with particular discipline and syntax rules. However, according to the skeptic, there are no facts determining the compliance of meaning ascriptions with such rules. Therefore, we cannot attribute deflationary truth-conditions to meaning ascriptions. The problem with this argument is that it relies on an over-application of Kripke’s original argument, conflating skepticism about rule-following with skepticism about rule conformity. Originally, the skeptic’s argument was directed only against the former. Kripke’s original argument on rule-following does not inherently deny the possibility of determining whether an action conforms to a rule. In contrast, it raises questions about the possibility of rule-following on the basis of the observation that an agent’s actions conform with two different, but in some respect incompatible, rules – the rule of addition and rule of quaddition. Therefore, given the first interpretation of the wrong presupposition argument, Miller exaggerates Kripke’s comments by extending Kripke’s skepticism from facts regarding rule-following to facts regarding rule-conformity, whereas Kripke’s skepticism already presupposes rule-conformity.

Nevertheless, we may interpret the Granted Rule Argument as a claim that attributing deflationary truth-conditions to meaning ascriptions requires an agent to follow particular discipline and syntax rules. Given skeptic’s remarks implying that there is no fact determining whether an agent follows specific discipline and syntax rules, we are obliged to admit that he does not mean anything by such rules. Nevertheless, we can answer this objection by rejecting the closure principle of assertibility of meaning ascriptions. By doing so, we can argue that S is following disciplinary norm N1 despite the lack of any facts determining that S follows N1 rather than N2. Therefore, we can assert that an agent making a given meaning ascription is following a specific subsidiary norm, even in the absence of facts that justify refuting alternative explanations for the agent’s actions. Thus, by rejecting the closure principle, we can also refute the Granted Rule Argument. Hence, we can rebut Miller’s argument that minimal factualism collapses under the skeptical remarks.

6 Conclusions

The primary objective of this paper was to counter Miller’s arguments against the minimalist version of the factualist interpretation of the skeptical solution. Miller’s initial argument posits that this position aligns with a form of semantic primitivism, a stance explicitly rejected by Kripke’s Wittgenstein. Consequently, Miller concludes that the minimalist view is an implausible reading of the skeptical solution. His second argument contends that minimal factualism assumes the conformity of meaning ascriptions with specific rules of discipline and syntax—a possibility undermined by Kripke’s skeptic.

In response to the first argument, I stated that the skeptic’s objection to primitivism aims to undermine the notion that primitive, sparse facts might play a causal-explanatory role in an agent’s use of linguistic expressions. However, from the standpoint of the minimal factualism, semantic facts are somewhat minimal and abundant, implying they do not play a causal-explanatory role and, thus, fall outside the scope of the skeptic’s objections.

To demonstrate the plausibility of the factualist interpretation as a reading of the skeptical solution, I focused on the underlying assumption of the skeptical solution—the rejection of the closure principle of assertibility of meaning ascriptions. As argued, this rejection can only be performed if we assume that semantic facts are abundant, aligning with the minimalist view.

Subsequently, in response to Miller’s second argument, I introduced the Kantian distinction between conformity to a rule and following a rule. Accordingly, I argued that Miller’s argument can be interpreted in terms of conformity to a rule and following a rule. Nevertheless, I demonstrated that a reading of this argument in terms of conformity to a rule is flawed, as it exaggerates Kripke’s remarks. In turn, its interpretation in terms of following a rule may be addressed on the basis of the rejection of the closure principle.

In summary, I have demonstrated that Miller’s arguments against the minimalist version of the factualist interpretation of the skeptical solution are not sound. However, it is essential to note that it does not necessarily imply that the factualist interpretation provides the best account of the skeptical solution. The debate over which perspective offers the most compelling interpretation of the skeptical solution is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, in my opinion, refuting Miller’s arguments should enhance the credibility of the minimalist version of the factualist interpretation as an account of the skeptical solution.

References

Asay, J. (2013). The primitivist theory of truth. Cambridge University Press.

Asay, J. (2021). Primitivism about truth. In M. Lynch, J. Wyatt, J. Kim, & N. Kellen (Eds.), The nature of truth: Classic and contemporary perspectives (pp. 525–538). MIT Press.

Boghossian, P. (1990). The status of content. The Philosophical Review, 99(2), 157–184.

Boyd, D. (2017). Semantic non-factualism in Kripke’s Wittgenstein. Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy, 5(9). https://doi.org/10.15173/jhap.v5i9.3009.

Byrne, A. (1996). On misinterpreting Kripke’s Wittgenstein. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 56(2), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.2307/2108524.

Davies, D. (1998). How sceptical is Kripke’s ‘Sceptical solution?’. Philosophia, 26, 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02380061.

Dretske, F. (1970). Epistemic operators. The Journal of Philosophy, 67(24), 1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.2307/2024710.

Dretske, F. (2005). Is knowledge closed under known entailment? The case against closure. In M. Steup, & E. Sosa (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (pp. 13–26). Blackwell.

Edwards, D. (2013). Truth as substantive property. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 91(2), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048402.2012.686514.

Goodman, N. (1983). Fact, fiction, and forecast. Harvard University Press.

Guardo, A. (2020). Meaning relativism and subjective idealism. Synthese, 197(9), 4047–4064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-01917-9.

Hattiangadi, A. (2007). Oughts and thoughts: Scepticism and the normativity of meaning. Oxford University Press.

Horwich, P. (1998). Truth. Oxford University Press.

Kripke, S. (1982). Wittgenstein on rules and private language. Harvard University Press.

Kusch, M. (2006). A sceptical guide to meaning and rules. Defending Kripke’s Wittgenstein. Acumen Publishing.

Miller, A. (2010). Kripke’s Wittgenstein, factualism and meaning. In D. Whiting (Ed.), The later Wittgenstein on meaning. Palgrave Macmillan.

Miller, A. (2011). Rule-following skepticism. In S. Bernecker, & D. Pritchard (Eds.), The Routledge companion to epistemology. Routledge.

Miller, A. (2020). What is the sceptical solution. Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy, 8(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.15173/jhap.v8i2.4060.

Moore, G. E. M. (1953). Some main problems of philosophy. Allen and Unwin.

Posłajko, K. (2017). Semantic deflationism, public language meaning, and contextual standards of correctness. Studia Semiotyczne, 31(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.26333/sts.xxxi1.04.

Strawson, P. (1950). Truth. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 24, 129–156.

Šumonja, M. (2021). Kripke’s Wittgenstein and semantic factualism. Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy, 9(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.15173/jhap.v9i3.4370.

Wilson, G. M. (1994). Kripke on Wittgenstein and normativity. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 19, 366–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4975.1994.tb00295.x.

Wilson, G. (1998). Semantic realism and Kripke’s Wittgenstein. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 58(1), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/2653632.

Wilson, G. (2003). The skeptical solution. In R. Dottori (Ed.), The legitimacy of truth. Lit Verlag.

Wright, C. (1984). Kripke’s account of the Argument Against Private Language. The Journal of Philosophy, 81(12), 759–778. https://doi.org/10.2307/2026031.

Wright, C. (1992). Truth and objectivity. Harvard University Press.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Poland) research grant DI2018 001648 as part of “Diamentowy Grant” program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wieczorkowski, M. The Factualist Interpretation of the Skeptical Solution and Semantic Primitivism. Philosophia 52, 341–354 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-024-00731-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-024-00731-7