Abstract

The modal collapse objection to classical theism has received significant attention among philosophers as of late. My aim in this paper is to advance this blossoming debate. First, I briefly survey the modal collapse literature and argue that classical theists avoid modal collapse if and only if they embrace an indeterministic link between God and his effects. Second, I argue that this indeterminism poses two challenges to classical theism. The first challenge is that it collapses God’s status as an intentional agent who knows and intends what he is bringing about in advance. The second challenge is that it collapses God’s providential control over which creation obtains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A positive ontological item is anything that exists (i.e., anything that has being or is within reality). Second, nothing in my article hangs on a precise and formalized account of intrinsicality. I follow David Lewis: “We distinguish intrinsic properties, which things have in virtue of the way they themselves are, from extrinsic properties, which they have in virtue of their relations or lack of relations to other things” (1986, p. 61). Thus, intrinsic features (or predicates) characterize S as it is in itself, without reference to things wholly apart from or outside of or disjoint from S. By contrast, extrinsic features (or predicates) characterize S as it relates to or connects with (or else fails to relate to or connect with) something wholly apart from or outside S. For an overview of debates concerning intrinsicality and extrinsicality, see Marshall and Weatherson (2018).

This understanding of parts in connection with DDS is found in Spencer (2017, p. 123), Brower (2009, p. 105), Stump (2013, p. 33), Grant (2012, p. 254), Schmid and Mullins (2021), Leftow (2015, p. 48), Leftow (2009, p. 21), Sijuwade (2021), Kerr (2019, p. 54), and Dolezal (2011, p. xvii), inter alia.

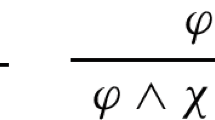

Two notes. First: I follow the standard usages of possibility, contingency, and necessity in modal collapse debates. I shall also use possible worlds as a semantic device without ontological import. As I use it, a possible world is just a complete, maximal, or total way reality could be. Something exists (obtains, is true) contingently if and only if it exists (obtains, is true) in some possible worlds but not others. In other words, it is possibly within reality, but it is also possibly absent from reality. It can fail to exist (obtain, be true). By contrast, something exists (obtains, is true) necessarily if and only if it exists (obtains, is true) in all possible worlds. It must be in reality; it cannot fail to exist. Second: on the classical theistic commitment to God’s creative act extending to any item distinct from God, see Rogers (1996, p. 167), Bergmann and Brower (2006, p. 361), Grant (2019, ch. 1), and Schmid and Mullins (2021).

Thus, I am setting aside altogether modal collapse arguments based on divine knowledge. For explorations into such arguments, see Schmid and Mullins (2021), Grant (2012), and Grant and Spencer (2015). Going forward in the paper, I will use ‘modal collapse argument(s)’ to refer only to action-based modal collapse arguments.

One might think that a deterministic causal link follows from the fact that it cannot be the case that both (i) an omnipotent being intends or wills to bring x about and yet (ii) x fails to come about. But this is untrue if ‘is an act of intending or willing to bring x about’ is an extrinsic predication that depends (in part) on whether or not x itself comes about. See Schmid (2021) for more on this point.

I say ‘my proposed solution’, but the idea is quite similar to Nemes’ point concerning the difference principle and Waldrop’s point about modal collapse arguments hinging on essentiality thesis (E). I demarcate my proposal because I think indeterministic causation is the root cause (if you’ll pardon the pun) of the falsity (under DDS) of both the difference principle and thesis (E). It is precisely because God indeterministically causes his effects that there is no cross-world difference in God despite cross-world differences in creation, and it is precisely because God indeterministically causes his effects that something’s being a divine creative act does not entail that it is essentially such.

I develop and defend Biconditional Solution in greater detail in Schmid (2021).

‘Will’ expresses not a temporally posterior but rather a causally posterior sense. My uses of ‘will’, ‘was’, ‘prior’ and ‘posterior’ at relevant points in the main text will henceforth express a causal sense thereof.

Another potential problem—one I won’t explore beyond this footnote—is that there is something counterintuitive about creation somehow retroactively making it the case that God’s act in PRIOR was an act of intending to actualize this creation. For creation doesn’t exist in PRIOR, and yet somehow it grounds or explains the relevant true predication in PRIOR. More can be said on this point, but that suffices for a footnote.

We should remember that this is simply concomitant with classical theism. God can do nothing distinctive—i.e., he can perform no act he would not otherwise have performed (since God is identical to God’s act)—to ensure or settle or determine whether a given creation obtains. (This is bolstered by Biconditional Solution: from God’s act, any possible effect whatsoever can indeterministically come about. God’s act therefore cannot ensure (settle, determine) that a given creation obtains.)

Some of the prominent accounts of (direct) control in the literature likewise support this result. Consider, e.g., the account found in Levy (2011) and Coffman (2007) and summarized in Carusso (2018): “[A]n agent has direct control over an event if the agent is able (with high probability) to bring it about by intentionally performing a basic action and if the agent realizes that this is the case (N. Levy, 2011: 19; cf. Coffman, 2007)”. Crucially, though, the classical theistic God cannot perform some action such that the action has a high probability of bringing about a precise effect. Instead, God’s one action (with which he is identical) can bring about (i.e., actualize) any possible world whatsoever—any possible universe or multiverse with any possible laws and inhabitants (as well as the utter absence of a universe). Nothing in the act, then, distinctively favors a precise effect over another, given that all possible worlds are equally open consequences of that one, simple act. Thus, at least on the aforementioned account of direct control, the classical theistic God lacks direct control over which precise effect results from his act.

Recall the temperature case or the button-lottery case: fixing all the facts about you and your act(s) was perfectly compatible with any of those infinitely many values coming to be, and, plausibly, it was precisely because of this that you were not in control over whether some particular temperature comes to be.

And notice that under classical theism (but not non-classical theism), the indeterminism is, indeed, located downstream of God’s act(s). I will say more about this in response to the second objection.

For some treatments of the objection (and intimately related worries), see—among many others—van Inwagen (1983, pp. 142–150; 2002), Mele (1999, 2006), Haji (2001, 2003, 2013), Almeida and Bernstein (2003, 2011), Levy (2005), Franklin (2011), Carusso (2018), and Clarke (2000, 2002, 2003). See also Clarke and Capes (2017, §2.2) and the references therein.

My purpose is not to defend such accounts, or to claim that they succeed in averting the luck objection. If the accounts do succeed, then it is significant that they are unavailable to classical theism but available to non-classical theism and/or human freedom, since this indicates a problem unique to classical theism. If the accounts don’t succeed, then the classical theist is still in a poor position with respect to control. (Though, they would be accompanied by the non-classical theist and the libertarian about human freedom.) Either way, the providential collapse argument has teeth. (Assuming, of course, that my arguments for the unavailability to classical theism of such accounts succeed.)

In such a case, God’s acts are differentially dependent on a multiplicity of reasons and necessarily existent divine psychological states (desires, plans, etc.) across worlds. But this seems to straightforwardly introduce multiplicity into the Godhead—positive ontological items numerically distinct from but nevertheless within God. (If an act is dependent on one or more reasons, surely those reasons exist.) If correct, this also debars the proponent of DDS from using a model of divine action developed in O’Connor (1999). For O’Connor is explicit that, under his model, in the case of God (the agent) creating the contingent order, “there’s just (i) an agent with reasons for various possible creations, and (ii) a relation of dependency between that agent and the actual creation, such that the product might have been utterly different, and the agent utterly the same” (1999, p. 409). The existence of a multiplicity of reasons seems to introduce a multiplicity of existents within God, something debarred by DDS. (I will consider an objection to this point later.)

Moreover, as Mele (2006, p. 55) points out, “O’Connor does not place cross-world differences in agents’ doings out of bounds in the context of free will; in fact, such differences are featured in his objection from chance to event-causal libertarians.” And, of course, such cross-world differences in agents (and/or their doings) are explicitly debarred by DDS.

A hyperintensional context is one in which one cannot intersubstitute necessarily co-referring expressions (else: necessarily equivalent expressions) within a sentence without potentially changing its truth value. In other words, hyperintensional contexts are characterized by the failure of intersubstitutability of necessarily co-referring expressions salva veritate. Intersubstitutability salva veritate fails despite identical intensions. Cf. Berto and Nolan (2021).

Aquinas, for instance, explicitly denies that the divine substance can be essentially referred to other things—cf. Summa Contra Gentiles II, ch. 12 and De Potentia Q7, A8. (And note that we are talking about, in the main text, an intrinsic directedness-toward and referral-to. And whatever is intrinsic to God is essential to God, under DDS.)

Thanks to an anonymous referee for very helpful feedback on an earlier draft.

References

Almeida, M., & Bernstein, M. (2003). Lucky libertarianism. Philosophical Studies, 113, 93–119.

Almeida, M., & Bernstein, M. (2011). Rollbacks, endorsements, and indeterminism. In R. Kane (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of free will (2nd ed., pp. 484–495). Oxford University Press.

Aquinas. (n.d.-a) Summa Contra Gentiles.

Aquinas. (n.d.-b) De Potentia.

Augustine. (n.d.) The City of God.

Bergmann, M., & Brower, J. E. (2006). A theistic argument against platonism (and in support of truthmakers and divine simplicity). In D. W. Zimmerman (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaphysics. Oxford University Press.

Berto, F. & Nolan, D. (2021). Hyperintensionality. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hyperintensionality/

Broadie, A. (2010). Scotistic metaphysics and creation ex nihilo. In D. B. Burrell, J. M. Soskice, & W. R. Stoeger (Eds.), Creation and the God of Abraham (pp. 53–64). Cambridge University Press.

Brower, J. E. (2009). Simplicity and aseity. In T. P. Flint & M. C. Rea (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of philosophical theology. Oxford University Press.

Brunner, E. (1952). The christian doctrine of creation and redemption. Lutterworth Press.

Carusso, G. (2018). Skepticism about moral responsibility. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/skepticism-moral-responsibility/

Clarke, R. (2000). Modest libertarianism. Philosophical Perspectives, 14, 21–45.

Clarke, R. (2002). Libertarian views: Critical survey of noncausal and eventcausal accounts of free agency. In R. Kane (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of free will (1st ed., pp. 356–385). Oxford University Press.

Clarke, R. (2003). Libertarian accounts of free will. Oxford University Press.

Clarke, R. and Capes, J. (2017). Incompatibilist (nondeterministic) theories of free will. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/incompatibilism-theories/

Coffman, E. J. (2007). Thinking about luck. Synthese, 158(3), 385–398.

Craig, W. L. (2001). God, time and eternity. The coherence of theism II: Eternity. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Dolezal, J. E. (2011). God without parts: Divine simplicity and the metaphysics of God’s absoluteness. Pickwick Publications.

Dolezal, J. E. (2017). All that is in god: Evangelical theology and the challenge of classical christian theism. Reformation Heritage Books.

Duby, S. J. (2016). Divine simplicity: A dogmatic account. Bloomsbury.

Fakhri, O. (2021). Another look at the modal collapse argument. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion, 13(1), 1–23.

Franklin, C. E. (2011). Farewell to the luck (and mind) argument. Philosophical Studies, 156, 199–230.

Franklin, C. E. (2012). The assimilation argument and the rollback argument. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 93, 395–416.

Grant, W. M. (2012). Divine simplicity, contingent truths, and extrinsic models of divine knowing. Faith and Philosophy, 29, 254–274.

Grant, W. M. (2019). Free will and god’s universal causality: The dual sources account. Bloomsbury Academic.

Grant, W. M., & Spencer, M. K. (2015). Activity, identity, and God: A tension in Aquinas and his interpreters. Studia Neoaristotelica, 12, 5–61.

Haji, I. (2001). Control conundrums: Modest libertarianism, responsibility, and explanation. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 82, 178–200.

Haji, I. (2003). Alternative possibilities, luck, and moral responsibility. The Journal of Ethics, 7(3), 253–275.

Haji, I. (2013). Event-causal libertarianism’s control conundrums. Grazer Philosophische Studien, 88, 227–246.

Hughes, C. (2018). Aquinas on the nature and implications of divine simplicity. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion, 10, 1–22.

Kane, R. (1999). Responsibility, luck and chance: Reflections on free will and indeterminism. Journal of Philosophy, 96, 217–240.

Kerr, G. (2019). Aquinas and the metaphysics of creation. Oxford University Press.

Lebens, S. (2020). The principles of Judaism. Oxford University Press.

Leftow, B. (2009). Aquinas, divine simplicity and divine freedom. In K. Timpe (Ed.), Metaphysics and god: Essays in honor of Eleonore Stump (pp. 21–38). Routledge.

Leftow, B. (2012). God and necessity. Oxford University Press.

Leftow, B. (2015). Divine simplicity and divine freedom. Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association, 89, 45–56.

Levy, N. (2005). Contrastive explanations: A dilemma for libertarians. Dialectica, 59(1), 51–61.

Levy, N. (2011). Hard luck: How luck undermines free will and moral responsibility. Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1986). On the plurality of worlds. Blackwell.

Marshall, D. & Weatherson, B. (2018). Intrinsic vs. extrinsic properties. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/intrinsic-extrinsic/

Mele, A. (1995). Autonomous agents. Oxford University Press.

Mele, A. (1999). Ultimate responsibility and dumb luck. Social Philosophy and Policy, 16, 274–293.

Mele, A. (2006). Free will and luck. Oxford University Press.

Moreland, J. P., & Craig, W. L. (2003). Philosophical foundations for the christian worldview. InterVarsity Press.

Mullins, R. T. (2013). Simply impossible: A case against divine simplicity. Journal of Reformed Philosophy, 7, 181–203.

Mullins, R. T. (2016). The end of the timeless god. Oxford University Press.

Mullins, R. T. (2021). Classical theism. In J. M. Arcadi & J. T. Turner (Eds.), T&T Clark handbook of analytic theology. T&T Clark.

Nemes, S. (2020). Divine simplicity does not entail modal collapse. In C. F. C. da Silveira & A. Tat (Eds.), Roses and reasons: Philosophical essays. Eikon.

O’Connor, T. (1999). Simplicity and creation. Faith and Philosophy, 16(3), 405–412.

O’Connor, T. (2000). Persons and causes. Oxford University Press.

Pruss, A. R. (2008). On two problems of divine simplicity. In J. L. Kvanvig (Ed.), Oxford studies in philosophy of religion (pp. 150–167). Oxford University Press.

Rice, R. L. H. (2016). Reasons and divine action: A dilemma. In K. Timpe & D. Speak (Eds.), Free will and theism: Connections, contingencies, and concerns (pp. 258–276). Oxford University Press.

Rogers, K. A. (1996). The traditional doctrine of divine simplicity. Religious Studies, 32, 165–186.

Schmid, J.C. and Mullins, R.T. (2021). The aloneness argument against classical theism. Religious Studies.

Schmid, J. C. (2021). The fruitful death of modal collapse arguments. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11153-021-09804-z

Shabo, S. (2014). Assimilations and rollbacks: Two arguments against libertarianism defended. Philosophia, 42, 151–172.

Sijuwade, J. R. (2021). Divine simplicity: The aspectival account. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion.

Spencer, M. K. (2017). The flexibility of divine simplicity: Aquinas, Scotus, Palamas. International Philosophical Quarterly, 57(2), 123–139.

Stump, E. (2013). The nature of a simple God. Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association, 87, 33–42.

Tomaszewski, C. (2019). Collapsing the modal collapse argument: On an invalid argument against divine simplicity. Analysis, 79(2), 275–284.

Vallicella, W.F. (2019). Divine simplicity. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/divine-simplicity/

van Inwagen, P. (1983). An essay on free will. Clarendon.

van Inwagen, P. (2002). Free will remains a mystery. In R. Kane (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of free will (1st ed., pp. 158–177). Oxford University Press.

Waldrop, J. W. (2021). Modal collapse and modal fallacies: No easy defense of simplicity. American Philosophical Quarterly.

Ward, T. M. (2020). Divine ideas. Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

There is no funding, conflicts of interest, or anything of this sort.

Additional information

There is another reference anonymized for peer review

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schmid, J.C. From Modal Collapse to Providential Collapse. Philosophia 50, 1413–1435 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-021-00438-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-021-00438-z