Abstract

In this paper I examine Hugh Burling’s inspiring proposal that the reference of ‘God’ is determined by the description: ‘the being worthy of our worship’. I argue that a more detailed analysis of the notion of being worthy of our worship leads to the conclusion that the proposed description is paradoxical, and cannot fulfill the role Burling would like it to play in determining the reference of the term ‘God’. Subsequently, I provide several examples implying that (1) being worthy of our worship is a necessary condition for any candidate to be the referent of the term ‘God’, but (2) the semantics of ‘God’ is considerably more complicated than Burling takes it to be. Finally, I show that religious people who use the word ‘God’ are either idolatrous or trapped in an apophatic paradox of the reference of ‘God’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In a recent paper, Hugh Burling (2019) poses some important questions when he writes: “What should our semantic theory for the term ‘God’ be? How is it that when we use the term ‘God’ referentially, it really picks out God? Alternatively, what is picked out by ‘God’?” (p. 343). He himself advocates a view according to which “the reference for ‘God’ is determined by the definite description ‘the being that is worthy of our worship’” (ibid). He regards his position as being a rival of the two other theories mostly endorsed by contemporary philosophers, these being the ‘Causal Reference’ theory (CR) and the traditional ‘Descriptive Denotation’ view (DD). The principal reason invoked by Burling in support of his theory is that a plausible conception of the reference of ‘God’ should meet two focal criteria, which he calls ‘the criterion of accessibility’ and ‘the criterion of scope’.

In this article, I argue that a more detailed analysis of the notion of being worthy of worship leads to the apophatic conclusion that this description is paradoxical, and cannot fulfill the role Burling would like it to play. Finally, I argue that the semantics of ‘God’ is considerably more complicated than he takes it to be.

* * *

Burling holds that “the reference of ‘God’ is determined via the implicit sense of the term, the definite description ‘the being that is worthy of our worship’” (p. 343). He takes natural languages to be rule-governed phenomena. He remarks, however, that “whether or not a ‘rule’ obtains within a practice does not depend on whether the words involved in the practice are always used in exactly the way that rule implies” (p. 346). What is even more important is that he rejects the view that “a rule’s obtaining depends on unanimous agreement with that rule, among practitioners, were it described back to them” (p. 346). Seen from such a perspective, it is reasonable to state, as Burling does, that “we find out what a word means by looking at how it works” when used in what he calls “linguistic practices” (p. 345), and that “people’s typical use of language is a universally available source of data about how words ‘work’” (p. 345). Thus, the implicit character of the sense of the term ‘God’ implied by Burling’s theory means that it is not the conscious ideas of language users that count, but rather the actual use of the term in question.

Given such a view of language, Burling’s methodology demands, as an important starting point, a careful description of the relevant actual linguistic practices, and from this viewpoint Burling identifies two criteria that any adequate theory of the reference of ‘God’ ought to meet, calling these ‘accessibility’ and ‘scope’: “Accessibility concerns how easy it is for individual ‘God’-users to meet the conditions on successful reference imposed by the theory. Scope concerns how much disagreement about the nature of ‘God’s’ referent can be tolerated and how far our theory ‘draws together’ parties to disagreements in co-reference rather than letting them ‘split apart’ easily” (p. 343). It is important that those criteria are not assumed a priori, but rather are generalizations of his view of how instances of ‘God-talk’ actually look when they show up in our society and across world religions (cf. p. 350). Burling’s way of proceeding includes a “charitable hermeneutics”, which amount to “taking practitioners’ expressions at face value except in cases where we have strong reasons to suppose some literary or rhetorical trope is at work. It likewise means taking intended or purported reference to be evidence, if defeasible, of actual reference” (p. 345). Such a method of research leads him to conclude that his theory meets the criteria of accessibility and scope better than its rivals.

As regards accessibility, Burling states: “One easily discernible feature of the theistic religious practice is that most humans seem capable of playing it successfully. It doesn’t seem to require ‘special training’. Although we might use it better if we have certain kinds of training, children seem to be able to speak as intelligibly about and to God as they can about and to creatures. So, we can infer that God is highly linguistically accessible via the term ‘God’”. As a consequence, “one can successfully refer to God by using ‘God’, without needing a sophisticated conceptual apparatus related to one’s use or understanding of the term” (p. 346). This last conclusion poses a serious threat to the DD view, as according to the latter, the denotation of ‘God’ as employed by a given individual will be dependent on the concept of God they have: that is, without a conceptual apparatus enabling them to form an adequate concept of God, they will be unable to refer to God successfully.

There are, in addition, empirical grounds for taking the scope criterion into consideration. Firstly, there is the observation that, for instance, when “Christians, Jews, Muslims and (many) Hindus disagree, they appear to disagree about the nature of the same object”. This, and other similar observations, lend support to the thesis that “users of the theistic religious linguistic practice should be able to co-refer to God when they use the same term as each other – even when they strongly disagree about what the thing each calls ‘God’ is like” (p. 347). Meanwhile, a second fact invoked by Burling as a justification for this criterion is the translatability of the term ‘God’, which makes it possible that “missionaries seem able to make theistic claims understood across very different cultures, often without shared linguistic histories” (p. 348).

Burling argues that these facts pertaining to co-reference and translatability fail to be explained either by the classic descriptive denotation theory or by the causal theory of reference. The former’s basic assertion, to the effect that the name in question is to be regarded as an abbreviation for a definite description and that it therefore refers to whatever fits that description, is inconsistent with the fact that one can observe co-reference between language users who nevertheless disagree as to the basic features of the common referent. At the same time, the latter faces difficulties explaining co-reference across groups of language users that do not share a common linguistic history, as in such cases one can hardly identify a common causal chain leading to a putative referent of ‘God’.

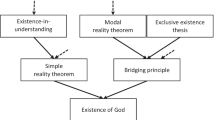

Burling, on the other hand, claims that co-reference in those cases can be explained if one is prepared to assume that the reference of the term ‘God’ is established by a highly specific definite description: namely, ‘the being worthy of our worship’. (We shall hereinafter refer to this position, theory or thesis as ‘WW’.) The latter description does not say anything directly about the characteristics of God. This is why, according to Burling, in order to master this concept one need not develop any metaphysical conception of God. The only competence called for is that of being able to worship properly and, as Burling himself assumes, “the concept and norms of worship (…) are learnt through ordinary social interaction from a young age” (p. 358). In other words, almost everyone understands what it means to worship, and is able to exhibit this attitude when appropriate. That, according to Burling, is why the WW-thesis meets the criteria of both accessibility and scope.

The crucial point in Burling’s reasoning is one that pertains to how religious worship is learnt. On his account, from early childhood on, people admire and praise others, such as parents, siblings, pop-stars, etc. Religious worship is a modification of such an attitude of veneration or praise toward non-divine objects. Yet here a crucial problem arises. As Burling himself is aware, the ‘Worship Worthiness’ (hereinafter ‘WW”) theory of the reference of ‘God’ requires that religious worship itself involve a ‘uniqueness thesis’, in the sense that the latter must then guarantee that only one being can be worthy of worship (see p. 358ff); otherwise, the description ‘the being worthy of worship’ will not suffice to pick out just one referent for the term. So the crucial question that arises here is that of what the differences are between religious worship (directed towards a unique object, i.e. God) and other similar attitudes – such as praise or veneration – that can be appropriately exhibited towards multiple different beings, as in the case of respected individuals or certain putative religiously significant non-divine beings (e.g., angels).

Burling notes that some thinkers (e.g., Bayne & Nagasawa, 2006) claim that theists have failed to explicate any such differences with sufficient clarity: i.e. it is said that they have not explained why the attitude of worship contrasts with other similar attitudes toward created beings, such as praise or admiration for angels or pop-stars, as a difference in kind rather than of degree only (cf. Bayne & Nagasawa, 2006, p.302). Burling expresses dissatisfaction with the account of Jeremy Gwiazda (2011), formulated as a response to the aforementioned paper (i.e. that of Bayne and Nagasawa), as it “appeals to controversial claims about the structure of value, in order to guarantee that only one being is worthy of worship” (Burling, 2019, p. 359). He prefers to take “the uniqueness thesis as data from the phenomenology of religion. And according to it, if it turns out that if anyone is worthy of worship, then the set of actually existing maximally excellent beings is a singleton. If there are multiple beings who are equally best, then no-one is referred to by ‚God’” (p. 360). Moreover, according to Burling, there is a further assumption that “must be taken as data from the phenomenology of worship: that although being the best is necessary for being worthy of worship, it is not sufficient. One must also surpass an absolute threshold of excellence”: i.e. it must be guaranteed that what is being worshipped is not the last evil being, but is in fact maximally excellent (ibid.).

* * *

In the next part of my paper I wish to revisit two philosophical analyses of certain important aspects of the notion of worship. Both are based on data drawn from the phenomenology of religion. They provide us with a more detailed account of the difference between worship and other forms of veneration or praise and, at the same time, help to elucidate what surpassing the absolute threshold of excellence amounts to. However, these same analyses pose a significant challenge for the WW-theory of the reference of ‘God’, at least in the version formulated by Burling.

The first of these pertains to Alasdair MacIntyre’s (1970) sketch of “how theism emerges from earlier forms of religion” (p. 176). In primitive religions, people worship particular concrete objects, such as stones or trees. However, what happens then is that “the primitive sceptic casts his first doubts” (ibid.), suggesting that such objects are in fact not worthy of worship. In response to that accusation, “the worshipper purges his divinity of particularity, tries to remove those points in which his god is less than he might be” (p. 176–177). At each stage of this process “scepticism drives him on, showing him always that his god is less than he might be so long as he remains an object, a being, even if the highest” (p. 177).

A highly similar but more detailed view has been presented by John N. Findlay (1948). The latter’s position also merits consideration here on account of the fact that he explicitly refuses to determine the reference of ‘God’ by appeal to any definite description such as would try to capture directly certain characteristics of the deity, stating that “we shall, however, choose an indirect approach, and pin God down for our purposes as the ‘adequate object of religious attitudes’” (Findlay, 1948, p. 177), where such a view in fact resembles Burling’s to some degree. Findlay claims that “a religious attitude was one in which we tended to abase ourselves before some object, to defer to it wholly, to devote ourselves to it with unquestioning enthusiasm, to bend the knee before it, whether literally or metaphorically” (ibid.). His formulation here can be plausibly rendered using the expression ‘the object worthy of worship’.

Findlay, however, argues not only that “all attitudes, we may say, presume characters in their objects, and are, in consequence, strengthened by the discovery that their objects have these characters, as they are weakened by the discovery that they really haven’t got them”, but also that it should be so: i.e. that if a given attitude is to be regarded as justified or normal, there should obtain a certain adequacy between the attitude and the nature of the object of this attitude (see p. 178). In this context, he notes that an attitude of worship presumes the superiority of its object to the worshipper. Moreover, it is not appropriate to worship anything limited, for “all limited superiorities are tainted with an obvious relativity, and can be dwarfed in thought by still mightier superiorities, in which process of being dwarfed they lose their claim upon our worshipful attitudes” (p. 179). A worshipper discovers that she cannot worship anything which stands “surrounded by a world of alien objects, which owe it no allegiance, or set limits to its influence” (ibid.). In consequence “the proper object of religious reverence must in some manner be all-comprehensive: there mustn’t be anything capable of existing, or of displaying any virtue, without owing all of these absolutely to this single source” (p. 180).

The crucial step in Findlay’s reasoning – that which allows us to distinguish the worship of God from mere praise or veneration towards other beings – comes when he reminds us of the old distinction between two kinds of veneration: latreia and dulia. According to medieval Catholic theology, we owe the former solely to God, whilst other beings (e.g., angels and saints) deserve only the latter. The difference between these forms of praise consists in the fact that in the case of dulia, one admires or venerates some object relative to some condition – because of certain qualities possessed by it. For example, one venerates a saint because one recognizes that person to be good and holy. If one discovered that the person venerated had only pretended to be like this, and did not in fact possess goodness and holiness, one would then cease to venerate them. We can thus say that dulia is conditional veneration. As Findlay remarks, the fact that one venerates something only on condition that it possesses some qualities shows that in fact it is those qualities (e.g. goodness, holiness) that are the primary objects of praise/veneration.

Latreia, on the other hand, is unconditional worship. In this case, one does worship something for its own sake, and not because it has some property which it might or might not have. This is why, Findlay argues, “it would be quite unsatisfactory from the religious standpoint, if an object [of worship – P.S.] merely happened to be wise, good, powerful and so forth, even to a superlative degree, and if other beings had, as a mere matter of fact, derived their excellences from this single source” (ibid.). Findlay concludes that “we are led on irresistibly, by the demands inherent in religious reverence, to hold that an adequate object of our worship must possess its various qualities in some necessary manner. These qualities must be intrinsically incapable of belonging to anything except in so far as they belong primarily to the object of our worship” (p. 181). He notes that this was asserted by the scholastic doctrine that God is not merely good but indistinguishable from His – or anything else’s – goodness.

Findlay is aware that such a line of reasoning is also applicable to the very existence of the proper object of worship, and its relation to all other beings: “We can’t help feeling that the worthy object of our worship can never be a thing that merely happens to exist, nor one on which all other objects merely happen to depend. The true object of religious reverence must not be one, merely, to which no actual independent realities stand opposed: it must be one to which such opposition is totally inconceivable” (p. 180).

For Findlay, such conclusions make God’s existence an impossibility. His reason for thinking that this is so stems from the assumption that modern philosophical views “make it self-evidently absurd (if they don’t make it ungrammatical) to speak of such a Being and attribute existence to Him” (p. 182). As MacIntyre says, when seeking to summarize their common position, the process just described ends up with a “purely negative concept of God” as no “object at all” (MacIntyre, 1970, 177). According to this perspective, “even apparently positive assertions may conceal a negative content. To say, for example, that God is one, as Aquinas points out, is not to say how many Gods there are; it is to say that God is not among those things that are countable. Whatever we try to say of God turns out to be something that we must deny to be true of deity” (ibid.). If that is so, then the definite description “the being that is worthy of worship” is not a coherent one, owing to the fact that no being such as could be captured by a coherent concept is worthy of worship.

* * *

One should desist from just stopping here and simply dismissing the WW-theory, for several reasons. The first is that there have been religious thinkers – let us call them ‘apophatics’ – who were fully aware of what has just been seen to follow from such a “sublimation” of the concept of the proper object of worship, and who have fully embraced such consequences in the context of their own religious engagements. They regarded the aforementioned problems pertaining to the concept of worship not as an incoherence of a sort that ought to make them abandon their religious striving, but rather as a paradox showing them to be on the right path. Amongst Christians, we may count here Clement of Alexandria, Gregory of Nyssa, Pseudo-Dionysius, Meister Eckhart, Nicholas of Cusa, and others. Typically, these did not employ precise language to explicitly define terms such as ‘reference’, ‘denotation’, ‘connotation’, and so on. Nevertheless, they articulated their views about religious language sufficiently clearly for us to go on to interpret them in a more exact manner. For purposes of illustration, we shall consider one such example.

Gregory of Nyssa, writing in the fourth century, assumes that the divine nature “is to be conceived in all respects as infinite”. Such an assumption carries semantic consequences that are highly peculiar, to say the least, as “[i]n order then to mark the constancy of our conception of infinity in the case of the Divine nature, we say that the Deity is above every name: and ‘Godhead’ is a name. Now it cannot be that the same thing should at once be a name and be accounted as above every name.” (Gregory of Nyssa, 2020, 539)Footnote 1 In other words, Gregory gives voice here to a paradoxical utterance, trying to say something about God – or better, divinity – while at the same time acknowledging that the crucial word he is using, namely ‘Godhead’, by virtue of its very definition falls short of successfully referring to that to which it is intended to refer. Meanwhile, in another of his books, he proposes a highly interesting attempt to resolve this paradox. This takes the form of prayer: “Speak to me, you whom my soul loves – for so shall I name you, since your name is above every name and cannot be spoken or grasped by any rational nature. Therefore your name, which declares your goodness, is my soul’s attitude toward you” (Gregory of Nyssa, 2012, 69).Footnote 2 In the context of our present discussion concerning the proposal that ‘God’ refers to the being worthy of worship, what is striking is that Gregory equates the name ‘God’ here with his own religious attitude itself. He invokes this attitude using the term ‘love’, but – for the sake of argument – I propose to assume that love in the sense which Gregory has in mind, and worship, are to be taken as describing two aspects of the same attitude. Looked at from this perspective, the religious person is one who will acknowledge that, given the conditions that serve to justify an attitude of worship (religious love), the word ‘God/Godhead’ – which, taken at the face value, seems to refer to the proper object of this attitude – turns out under closer scrutiny not to refer to any object (for there is no object worthy of worship), and should rather be conceived as an abbreviated expression standing for the very religious attitude (of worship) itself.

The relationship between being on the right path and the apophatic paradox of worship is set forth even more clearly by Nicholas of Cusa. The process of sublimating the attitude of worship described so precisely by Findlay includes many affirmative statements about the putative object of worship, and Nicholas is himself aware of the necessity of such intellectual endeavour, stating as he does that “every religion, in its worshipping, must mount upward by means of affirmative theology”. However, he also admits that “the theology of negation is so necessary for the theology of affirmation that without it God would not be worshiped as the Infinite God but, rather, as a creature. And such worship is idolatry” (Nicholas of Cusa, 2020, 86).Footnote 3 Nicholas realizes that “all names are bestowed on the basis of a oneness of conception [ratio] through which one thing is distinguished from another” (Nicholas of Cusa, 2020, 75),Footnote 4 and that no object that can be identified over against some horizon distinguishable from it can be regarded as a proper object of religious striving. This is why Cusanus acknowledges that “no name can properly befit it” (ibid.).Footnote 5 In consequence, Nicholas is ready to admit the paradox that “we do not call true the statement that ‘God’ is His name; nor do we call that statement false, for it is not false that ‘God’ is His name. Nor do we say that the statement is both true and false” (Nicholas of Cusa, 2020') .Footnote 6

* * *

What are the implications of the above considerations for the reference of the term ‘God’? In order to answer this, let me first admit to being in agreement with Burling’s insistence that, when philosophizing about religious issues, we should start with the phenomenology of religion – or, to state the matter in a more Wittgensteinian manner, that prior to the attempt to create a “theory of reference” we should look carefully at the ways in which people use language, where in our case this means how they employ the word ‘God’.

A phenomenological investigation of religion – or, at least, a closer look at the ways in which people use the term ‘God’ – would clearly show that not all religious people agree with the sort of apophatic theism we find presented in Gregory of Nyssa or Nicholas of Cusa. Even if, when asked to whom they are referring when speaking about ‘God’, they were initially inclined to answer “to the object worthy of our worship”, after having worked through all of the above considerations they would remain confused, or would withdraw their initial declaration. This is because they, like many religious people, intend by ‘God’ to refer to some being that – if it exists – can somehow indeed be successfully referred to. As Jerome Gellman (1995) has pointed out, acts of naming “do not exist in solitude, but as part of a ‘naming game’”, and this “naming game determines what constitutes a proper candidate of naming within that game” (p. 536).Footnote 7 Gellman makes this remark in the context of his analysis of the causal theory of the reference of ‘God’, but I would suggest that this holds good where other competing conceptions are concerned, too: regardless of how people determine the reference of ‘God’, there is in most cases some category to which any referent of ‘God’ considered acceptable (to a given person or group) must belong.Footnote 8

My own position is that the phenomenology of religion lends support to the idea that the reference of ‘God’ is fixed in a more complicated way than Burling takes it to be. To be sure, the description ‘the being worthy of worship’ undoubtedly plays an important role in this process. Where the actually intended reference of many religious people is concerned, however, such categories as object or person play an equally important role. At the same time, many religious people, and probably most of those who subscribe to such monotheistic traditions as Judaism, Christianity and Islam, would regard the term ‘God’ as a proper name standing for the being who revealed himself to some historical figure that counts as foundational for their tradition (e.g. Abraham, Moses, Jesus, or Muhammad). In other words, a phenomenology of religion will allow for the hypothesis that the reference of ‘God’ is determined in the following slightly complicated way: people employ this term to refer to what was experienced by some historical figure (e.g. Jesus) or figures (e.g. Abraham, Moses and Jesus), and what was named ‘God’ by them, subject to the proviso that what was experienced and named as such by them belongs to the category personal being and is worthy of worship.

Problems arise, however, when it turns out that there is some discrepancy between those various conditions. In such an instance, a religious person must choose which of the factors determining the reference of a given term is the most important, and abandon or reinterpret the others accordingly.

Apophatics are ready to accept all the consequences of the above analysis of what is worthy of worship, and so reinterpret the categories of person and being, treating them as pragmatic yet inadequate metaphors. I suppose, however, that many religious people would reinterpret the concept of worship in a way that enables them to worship a putative concrete personal being.

Defending his position in this way would be an option for Burling himself.Footnote 9 After all, he declares that the particular conception of worship adopted in his paper – namely, the vision of it as an attitude that develops from ordinary attitudes of praise and veneration toward beings each of which one perceives as “the best being in some particular category”, and as one that connects worship-worthiness with absolute maximal excellenceFootnote 10 – is accepted by him only “for the sake of concision”, and that “an alternative argument to the one below should remain viable on alternative sets of properties and associated attitudes used to analyze worship” (cf. p. 359). One can suggest, then, that those other accounts of worship may discover that worship-worthiness – on this different account – consists in having some property different from absolute maximal excellence, and in that way avoid the apophatic problems raised above.

The problem with this solution is not only that no sketch of such an alternative account of worship has been given. A deeper difficulty resides in the fact that even if it were to be provided, one can reasonably doubt whether it would concern the same attitude as that analyzed above. Religious forms of life are highly complicated phenomena: every religious person exhibits a whole cluster of attitudes that can be described as ‘religious’. If there can be two (or more) different accounts of what is commonly called ‘worship’, each of which recognizes different properties as constitutive of worship-worthiness, then this could be taken to suggest that there is no single intuitive sense of ‘worship’ as widely shared within and across religions as Burling assumes it to be, but rather many attitudes called “worship” (i.e. different kinds of worship). Those attitudes may, respectively, have different beings as their proper objects: i.e. the description ‘the being that is worthy of our worship’ may pick out different beings as its referents, depending on the kind of worship one has is mind.

This, however, poses another threat to the WW-theory. Burling wants his theory to meet the criterion of scope to such an extent as to guarantee co-reference of the term ‘God’ across cultures and religions. Such a broad form of co-reference is guaranteed only if there is indeed one intuitive sense of ‘worship’ across (and also within) different religions and cultures. The apophatic way of conceiving worship suggests that this is not the case.

From the apophatic perspective, people who reinterpret the concept of worship in a way that enables them to count some particular being as worthy of worship are using ‘God’ to refer to something which is only a ‘god’ (an idol), and their worship is therefore idolatrous – or, rather, not worship at all.

This case is analogous to the one which Burling presents in one of the footnotes to his paper.Footnote 11 There he analyses the case of the religion of the ancient Israelites, who regarded Yahweh, whom they venerated, as one among many deities, comparable to others such as Baal or Astarte. Burling embraces the conclusion that the religious language game of those Israelites was not, after all, a theistic one: i.e. that, despite the fact that they claimed that “YahwehFootnote 12 is worthy of worship”, they were not, in the absence of a proper concept of worship, actually referring to God by ‘Yahweh’.Footnote 13

From the apophatic perspective, people who do not accept the apophatic implications of the conditions associated with worthiness of worship (as elucidated by Findlay and MacIntyre) find themselves in an analogous situation: they are failing to refer to God, and are doing so in a way that makes them idolatrous – i.e. using ‘God’ to refer to a being that is not divine (and that, as not worthy of worship, should therefore be called merely ‘god’, not ‘God’), and so are guilty of venerating (i.e. seeking to worship) a being not worthy of worship.Footnote 14 Apophatics would say that if Burling is right in claiming that “there is a narrower and intuitive sense of ‘worship,’ to which uniqueness seems to apply, at play in all contexts where religious language involves the term ‘God’ and not merely ‘god’” (Burling, 2019, p. 359), then it is only the apophatic individual, or a person ready to become such an apophatic, who is worshipping in that sense of the word.

The phenomenological study of religions, however, suggests that the place of the apophatic within religious traditions is a complicated one. On the one hand, viewing religious traditions in sociological terms, apophatic currents have not constituted the mainstream. On the other, many apophatics are recognized within those same traditions as renowned theological teachers, so their views are regarded as to some extent normative for the tradition in question.Footnote 15 If those suggestions are correct, then in most cases of linguistic utterance involving religious people using the term ‘God’, the reference of this word will not be determined by the description ‘the being worthy of our worship’ – in the theologically normative sense of ‘worship’. If, however, Burling’s critique of the two rival theories – namely, those of Descriptive Denotation and Causal Reference – is correct, as I mainly think it is,Footnote 16 then as regards the reference of ‘God’, religious people end up at best involved in the apophatic paradox.

Yet even if one dismisses the normative value of an apophatic account of worship, any theory in which the reference of the term ‘God’ is determined by the definite description ‘the being that is worthy of our worship’ ought to take into account the apophatic perspective – not only as a possible option, but also as a view on the issue that is actually held.

Notes

Gregory of Nyssa, On “Not Three Gods”, 539.

Gregory of Nyssa, Homily on the Song of Songs II, [61], 69.

Nicolas of Cusa, De docta ignorantia I, 26 (86).

Ibid., 24 (75).

Ibidem.

Nicholas of Cusa, Dialogus de Deo abscondito, 13.

For a similar view as regards CTR, also advocated in the context of discussing the reference of ‘God’, see: (de Ridder & van Woudenberg, 2014).

Cf. also (Bogardus & Urban, 2017, p. 189–191). Bogardus and Urban hold that regardless the theory of reference one assumes, there cannot be a “radical incongruity between an object and our conception of it”. That is to say, as I would put it, any act of reference assumes that the object referred to belongs to some (appropriate) category of beings. This thesis seems to be refuted by the example created by Alston (1988), in which it is the devil who, in some experiential encounter with a person, presents himself to that person as God. In this case, claims Alston, by uttering ‘God’ such a person would be referring to the devil, due to the fact that the reference is established by this experiential contact: i.e. the person described intends, by ‘God’, to refer to whatever they have encountered in that particular experience. It is not without importance, however, that in this example the devil presents himself as God – i.e. as the divine being. This suggests that (1) the person encountered by the devil has some concept of the divinity (since otherwise they would simply not have understood the devil’s self-presentations), and (2) the devil’s self-presentation as divine constitutes, for the person involved in the encounter, a reason of sorts for them to refer to the object of their experience using the term ‘God’. The intention of the person here as regards reference seems complex. As Alston himself admits, “one would not use ‘God’ to refer to x unless one firmly believed that x alone had certain characteristics” (p. 124). Yet even if he is right in remarking about this that it “falls short of showing that it is the possession of those characteristics that makes x the referent” (ibid.), the possession of certain characteristics by x, or x’s belonging to the proper category of being, does constitute the condition sine qua non of x’s being the referent of ‘God’. If this is so, then the word ‘God’ as used by the person in the example does not refer at all (cf. also Gellman, 1995, p. 537–538).

I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer of the first draft of my paper for pointing out such a possibility to me.

I.e. surpassing an absolute threshold of excellence.

Cf. Burling (2019), p. 365, n. 56.

Or the synonyms of this name, such as ‘El’ or ‘Adonai’.

At the same time, Burling is ready to admit that there was a way for them to refer to God: namely, if it so happened that God acted through (one of) them under the name of ‘Yahweh’. In that case, they could be said to have been successfully referring to God in the way described by the CR-theory. Even so, the problem runs deeper. If, as Gellman argues, the CR-theory requires the object experienced and named to belong to some category determined by the “naming game”, the ancient Israelites – whose category of deity was so different from the theistic one – could not be said to have been referring to God in any circumstances prior to their having first acquired the proper concept of worship.

The question of whether such a being exists or not is not relevant here, and lies beyond the scope of this paper.

This, for example, is the case with Gregory of Nyssa, who was quoted above. One can also mention such figures as Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, who had a huge impact on the whole of medieval Christian theology, or St. John of the Cross. The apophatic strand is even more important in the Hindu tradition: one can find many apophatic texts in the sacred Hindu scriptures – i.e. the Upanishads. A detailed examination of the apophatic strands within different religious traditions, however important it may be, nevertheless falls outside the scope of this paper.

A discussion of this issue exceeds the scope of the present article.

References

Alston, W. (1988). Referring to God. Philosophy of Religion, 24, 113–128.

Bayne, T., & Nagasawa, Y. (2006). The grounds of worship. Religious Studies, 42, 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034412506008420

Bogardus, T., & Urban, M. (2017). How to tell whether christians and Muslims Worship the same God. Faith and Philosophy, 34(2). https://doi.org/10.5840/faithphil201741178

Burling, H. (2019). The reference of ‘God’ revisited. Faith and Philosophy, 36(3). https://doi.org/10.5840/faithphil201987127

De Ridder, J., & van Woudenberg, R. (2014). Referring to, Believing in, and Worshipping the Same God. Faith and Philosophy, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.5840/faithphil20141104

Findlay, J. N. (1948). Can God’s existence be disproved. Mind, 57, 176–183.

Gellman, J. I. (1995). The name of God. Noûs, 29(4), 536–543.

Gregory of Nyssa. (2012). Homilies on the Song of Songs, transl. Richard A. Norris Jr, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta.

Gregory of Nyssa, On “Not Three Gods”, transl. P. Shaff and H. Wace, in: idem, Dogmatic Treatises, etc. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf205.html. Accessed 30 Oct 2020.

Gwiazda, J. (2011). Worship and threshold obligations. Religious Studies, 47, 521–525. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034412510000508

MacIntyre, A. (1970). The logical status of religious belief. In: S. Toulmin, R. W. Hepburn, A. MacIntyre (eds.), Metaphysical beliefs (2nd edition). Schocken Books.

Nicolas of Cusa, De docta ignorantia, transl. J. Hopkins, https://urts99.uni-trier.de/cusanus/content/fw.php?werk=13&ln=hopkins&hopkins_pg=1. Accessed 30 Oct 2020.

Nicolas of Cusa, Dialogus de Deo abscondito, transl. J. Hopkins, https://urts99.uni-trier.de/cusanus/content/fw.php?werk=21&lid=34932&ids=&ln=hopkins. Accessed 30 Oct 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.