Abstract

Communication is a well-known tool to promote cooperation and pro-social behavior. In this study, we examine whether minimal communication in form of public consent with a pre-defined cooperation statement is sufficient to strengthen cooperation in groups. Within the controlled environment of a laboratory experiment, we identify ways by which non-enforceable cooperation statements are associated with higher levels of cooperation in a public good setting. At first, the statement triggers selection; socially oriented individuals are more likely to make the cooperation statement. In addition, we can show that a behavioral change takes place once the statement is made. This change can be attributed to commitment arising from the pledge and to increased coordination between the interaction partners. Depending on the institutional context, these drivers can vary in strength. Comparing compulsory and voluntary cooperation statements, we find that both are effective in motivating higher contributions to the public good.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Many situations in daily life are characterized by a social dilemma structure; the collective is better off if everyone cooperates, but each individual has an incentive to defect and to act upon their self-interest. Hence, a central question in the social sciences is how to stimulate cooperation in group settings. Beside punishment and monitoring, communication has been shown to be an effective approach to strengthen pro-social behavior and cooperation in experimental studies (Ledyard 1995; Chaudhuri 2011).

Traditionally, studies which examine experimentally the impact of communication allow their participants to engage in an open discussion before play. While the messages in this communication format are typically costless and non-binding, previous findings suggest that players consider them as a serious opportunity to coordinate (Ostrom et al. 1992). Communication helps to establish a common cooperation norm and improves the understanding of the game (Kerr and Kaufman-Gilliland 1994). In consequence, pre-play communication can stimulate higher cooperation levels in the respective public good games. In reality, howsoever, open discussions between all relevant actors may be time-consuming or simply not feasible (Messick et al. 1983). To restrict communication in these settings may help to ease coordination.

In this study, we examine whether actors’ public consent to a cooperation statement is sufficient to promote cooperation within groups. The cooperation statement is pre-determined and non-binding, i.e., it is cheap talk, and this is known by all involved actors. Given that a procedure like this is easier to implement than a common communication forum, and at a lower cost, we believe that it is important to understand if and how these cooperation statements may affect behavior. For example, it is context-dependent whether a voluntary or compulsory statement is more suitable, but our results suggest pro-social behavior lasts longer when all players make the statement.

Previous research on communication in bilateral settings provides us with first indications as to why cooperation statements may be effective. Studies which give players the possibility to communicate before play, show that this exchange increases trust and trustworthiness. Individuals exhibit an aversion to lie (Gneezy 2005; Hurkens and Kartik 2009; Lundquist et al. 2009) and when they make a promise about future cooperation, they are likely to act consistently (Festinger 1957) and execute the promised behavior (Ellingsen and Johannesson 2004; Vanberg 2008; Charness and Dufwenberg 2006). Previous studies, however, also indicate that the engagement with the commitment may vary with the form of exchange. Conrads and Reggiani (2017), for example, show that cooperation promises are more likely in real-time communication than when communication is delayed. Social psychological studies, on the other hand, point to the importance of decision autonomy in commitments. Only when individuals feel that they have freely expressed the intention to help or to cooperate, they will feel committed to the promised behavior (Kiesler 1971; Linder et al. 1967; Schlesinger 2011). Elicited or pre-formulated promises, by contrast, have none or only a small effect on the consequent behavior (Charness and Dufwenberg 2010; Belot et al. 2010). At last, public promises have a stronger commitment effect than private pledges (Joule and Beauvois 1998); and being actively engaged in a pledge, i.e., statement-making is in some form effortful, increases the binding function (Kiesler 1971; Linder et al. 1967).

Regarding honesty, the effect of pre-play pledges seems to be particularly pronounced. Studies analyzing the impact of solemn oaths or honor codes on behavior show that when vows are taken, participants are more likely to reveal their true preferences (Jacquemet et al. 2013; Carlsson et al. 2013), are less likely to lie in the experiment (Mazar et al. 2008; Jacquemet et al. 2019; Beck et al. 2020) and coordinate better due to more truthful communication (Jacquemet et al. 2018). While a first study suggests that pledging a solemn oath may also have a positive spillover on cooperation (Hergueux et al. 2016), we, on contrast, study the effect on behavior directly: we examine whether public consent with a cooperation statement stimulates pro-social behavior in social dilemmas.

At last, this links our study to the literature on leader communication in social dilemmas. In these studies, one player has the opportunity to send a free message about intended contribution levels to the group. Whether these unilateral messages influence behavior depends on their credibility; Koukoumelis et al. (2012) find that contributions to the public good increase after the message, while in Dannenberg (2015) the leader message has rarely an effect. In the latter case, followers correctly anticipate that the leader will not realize her announced contribution level and hence do not get affected by the message.Footnote 1 In our experiment, we analyze a similar form of minimal communication, but the cooperation statement in our study differs in two fundamental aspects. First, the message is not endogenously chosen by one of the group members, but pre-determined by an external institution, that is by us, the experimenter. This allows us to determine what signal is offered as a coordination device. Second, we elicit a consent decision about the cooperation statement from each single player, so that everyone in the group has to take a stand.

With this design, we identify ways by which non-enforceable cooperation statements are empirically associated with higher levels of cooperation in a public good setting. At first, we identify whether selection takes place that is more socially oriented people make the statement. First, we determine whether selection occurs, i.e., whether people are more socially oriented in making the statement. Subsequently, using our within-subject design, we evaluate whether in addition to a potential selection effect behavioral change occurs. Subjects which make the statement contribute more after the pledge, and contribution levels are highest when all group members make the statement. We attribute this to improved coordination among the group members and analyze with a separate treatment condition whether the behavioral effects change when the cooperation statements are compulsory rather than voluntary. In our experiment, both types of statements increase cooperation and produce, on average, similar contribution levels.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we describe the experimental design and list the behavioral predictions. In Sect. 3, we present the experimental results. We conclude with some discussion and potential insights for practice in Sect. 4.

2 Experiment

2.1 Design

For this experiment, we employed a linear public good game with four players and a voluntary contribution mechanism. The experiment consisted of two stages, and in each stage, subjects played ten rounds of the public good game in partner matching. The first stage served as a baseline to measure heterogeneity and allows us to carry out a within-subject analysis.

At the beginning of each round, each subject was endowed with 20 Experimental Currency Units, which they could consume either privately or contribute to a public good. The payoff function was the following:

\( z_i \) denotes i’s contribution level, where \( 0 \le z_i \le 20 \) and \( 0.4*\sum \nolimits _{j=1}^n z_j \) presents the income from the project. Contributions to the public good increased the collective output, but the marginal per capita return of a contribution was less than one. A profit-maximizing individual may thus keep the entire endowment and free-ride on the contributions of the other players. Free-riding, however, diminishes the total welfare for all group members. After the first ten rounds, experimental groups were re-matchedFootnote 2 and the treatment variations were implemented. Participants were randomly allocated between three groups: Control, Voluntary and Compulsory. Table 1 summarizes the design.

In both treatment groups, a statement was offered to communicate the intended contribution behavior for the following rounds. The promise was directed to the other group members and stated that the player will make significant contributions to the project, that is at least 75% of the endowment in each of the following ten rounds. We have chosen a minimum of 75%, since it is higher than the generally observed average contributions in a public good game (40–60%), but lower than the Pareto optimal contribution level of 100%. Hence, some latitude in the contribution choices was possible.

In the first treatment group (Voluntary), participants simultaneously decided whether or not to make the statement. The players knew that these pledge decision would be publicized before the first contribution decision. In the second treatment group (Compulsory), players had to make the statement in order to proceed in the experiment. In both cases, it was made explicit that making the statement had no consequence on the set of possible future choices and did not limit the decisions later in the experiment. All participants who decided to pledge had to type in the following, “I promise to contribute each round at least 15 ECUs to the project.” According to research in social psychology (Linder et al. 1967; Kiesler 1971), commitment is stronger when individuals engage in the act of promise making. For this reason, we decided that subjects had to key in the statement.Footnote 3 Before the first contribution decision in Stage 2, all players in the treatment groups learned which players in their group (also) made the statement. In the second stage, Statement-Makers were consequently labeled.Footnote 4

To control how beliefs influenced the contribution choice, we asked subjects after their contribution decision to indicate their expectations about the contributions of the other players (first-order beliefs) and the guess of others’ expectations with respect to their own contributions (second-order beliefs). This belief elicitation was incentivized, following the quadratic scoring rule. After all subjects stated their beliefs, feedback was given about each group member’s individual contribution.Footnote 5

At the end of each stage, three rounds were randomly selected to determine the payments; one round for the contribution decision and two rounds for the accuracy of the beliefs. By this mechanism, we minimized wealth effects and prevented hedging within a stage.

2.2 Behavioral predictions and identification strategies

Under the assumption of purely self-serving and money maximizing behavior, contributions are expected to be 0 in all groups and stages. Statements, if they are made, are considered as meaningless by the group members and do not affect their contribution decisions. This also applies to the repeated setting of the game. A rational decision-maker will always break the promise in the last round and try to free-ride on the contributions of the others. Applying backward induction, the statement is consequently non-credible in all rounds of the game.

Empirical evidence, however, shows human behavior deviates fundamentally from these predictions. Contributions in public good games are on average between \( 40 - 60\% \) of the endowment in the first round of an experiment and deteriorate over the repetitions of the game (Ledyard 1995; Fehr and Gächter 2000; Chaudhuri 2011). Moreover, non-institutionalized, multilateral communication enhances the contribution levels significantly (Sally 1995; Bochet et al. 2006; Balliet 2009). Koukoumelis et al. (2012)’s study provides first evidence that also one-dimensional communication may be sufficient to motivate higher contribution levels.

Following these insights, public and institutionalized cooperation statements may be associated with higher contributions to the public good in our experiment. This reasoning finds also support in the bilateral promise literature. Individuals are reluctant to lie; either because the person has a preference for keeping their word (Ellingsen and Johannesson 2004; Vanberg 2008; Di Bartolomeo et al. 2019) or because the promisor does not want to go against the social norm of keeping a promise (Binmore 2006; Bicchieri and Lev-On 2007). Other authors argue that the effect is more indirect: the statement raises the expectations of others, the promisor anticipates this and is motivated by guilt aversion, that is the desire to avoid (the psychological costs from) disappointing the expectations of the interaction partners (Charness and Dufwenberg 2006; Ederer and Stremitzer 2017; Battigalli et al. 2013). Both theories, howsoever, suggest that making a statement increases contributions to the public good in our experiment.

In the case of the voluntary statements, higher contribution levels observed in Statement-Makers may have two origins: First, the statement is more appealing to people who generally contribute more. If they make the statement, while others do not, the decision to pledge can be interpreted as a (true) signal about one’s contributor type.Footnote 6

Hypothesis 1 (selection): Participants who contributed more in Stage 1 are more likely to make the statement.

The second origin for higher contributions of Statement-Makers is that a behavioral change took place and that subjects indeed increased their contributions after the pledge. In this case, commitment and coordination come into play. If making a statement triggers commitment, either due to a preference for promise-keeping or due to guilt aversion, and the interaction partners are aware of this, they may consequently also adapt their contribution behavior. To be more specific, if subjects observe other group members are making the statement, they expect higher group contributions in the future. Following conditional cooperation (Fischbacher et al. 2001), this change in beliefs motivates the subject to also contribute more to the public good. We see improved coordination, besides commitment to the promised behavior, as a source for an increase in pro-social behavior after a pledge.

Hypothesis 2 (behavioral change): Participants who make the statement subsequently increase their contributions to the public good in Stage 2 compared to their contributions in Stage 1.

Given our experimental design, the Voluntary treatment condition allows us to disentangle the selection aspect from the behavioral effect of the statement by comparing the behavior before and after the pledge (Stage 1 vs. Stage 2 contributions). We can evaluate whether participants who voluntarily choose to make the statement, have on average, higher contributions in Stage 1 (selection). And we can determine if participants who voluntarily made the statement, increase their contributions in Stage 2 compared to Stage 1 (behavioral change).

In regard to the comparison between the two statement forms, voluntary and compulsory, previous research suggests that forced statements trigger a weaker commitment than a voluntary statement (Kiesler 1971; Schlesinger 2011). And while lying or expectation-based guilt aversion (Charness and Dufwenberg 2006; Ederer and Stremitzer 2017; Battigalli et al. 2013) may still be in place, it can be expected that their effect is weaker than in the Voluntary setting, since also the interaction partners know that the statement was forced. To our knowledge, we are first to examine the eventual differences in behavior in the context of multilateral decision-making. Findings from studies analyzing the effect of bilateral promise-making support the hypothesis that the effect of compulsory promises is weak(er) (Linder et al. 1967; Charness and Dufwenberg 2010; Belot et al. 2010).

Hypothesis 3 (voluntary vs. compulsory): Participants who made a compulsory statement change their contribution behavior to a lesser extent than participants who made the promise voluntarily.

For the second driver of a behavioral change, namely improved coordination, we expect that it will matter how uniformly the cooperation statement gets adapted. Since we have no influence on the statement decision in the Voluntary treatment group, we will control for the resulting variations in the analysis. Of particular interest will be the behavioral change in groups in which all four players voluntarily decide to make the statement. We expect to observe particularly high contribution in these groups, since a strong coordination component will be paired with a self-driven commitment.

2.3 Experimental procedure

The experiment was conducted at the experimental laboratory of the Queensland University of Technology, we used the experimental software CORAL (Schaffner 2013) and the online recruitment system ORSEE (Greiner 2015). The experiment lasted for about an-hour-and-a-half. Sessions were equally distributed over the three treatment groups. Before participants could start the experiment, comprehension questions needed to be answered correctly. The average payment was 25.3 AUD (app. 18 USD). The data compromise observations of 192 individuals and 3840 decisions in total.

3 Results

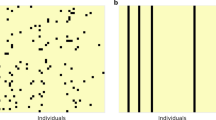

Starting with the average treatment effect, we examine the contribution levels in Stage 2 as opposed to Stage 1 in the control and the two treatment conditions (Table 2). Figure 1 depicts the corresponding differences in individual mean contributions. The graphical inspection suggests that when the game was played for the second time, average group contributions in the Control group were smaller. In the treatment groups, on contrast, average group contributions were higher than before.

In the following, we will use regression analyses to analyze these differences and to examine ways by which the non-enforceable cooperation statements can be associated with such higher contribution levels. At first, we will analyze the behavior in the Voluntary treatment group; we will identify whether there was selection in making the statement and whether behavior in addition changed after the pledge. In a second step, we will then compare how the effect of the statement varied when the pledge was voluntary or compulsory, and how the respective effects evolved over the course of interactions.

3.1 Voluntary statement

Table 3 presents the results of OLS regression models estimating the average individual contributions in Stage 1 and Stage 2 for the Control and Voluntary treatment group. The Control group’s contributions in Stage 1 serve as baseline.

Model 1 analyzes at an aggregate level the change in contribution behavior after the pledging possibility. We find the same dynamic as in Fig. 1; contributions in the Voluntary treatment group increased in Stage 2 (after the pledge), as opposed to the Control group, where contributions decreased. In consequence, contributions in Stage 2 of the Voluntary treatment group are significantly higher (\(F = 3.85\), \(p = 0.05\)) than contributions of the Control group in Stage 2, but also significantly higher than contributions in Stage 1 of the own treatment group (\(F = 4.84\), \(p = 0.03\)).

In the Voluntary treatment group, 48% of the participants decided to make the statement. In the following, we consider the behavior of these Statement-Makers separately. Participants who had the opportunity to make the statement, but chose not to, we will refer to as Non-Takers.

We hypothesized that cooperation statements would attract primarily those individuals who had previously contributed to the public good at a high level. Model 2 estimates pre- and post-contributions of Statement-Makers and Non-Takers and reveals that Statement-Makers indeed contributed already more in Stage 1 than Non-Takers (\(F=3.52\), \(p=0.062\)). Thus, we find support for the selection assumption of Hypothesis 1: subjects who choose to make the cooperation statement behave already before the pledge more socially. This finding is consistent with the results from other studies (Koessler et al. 2019; Koessler 2019) and is robust when we control for individual characteristics. Table 8 in the Appendix presents estimations on the likelihood of making a statement. Besides past contribution behavior, we find that gender is a predictor for statement-making: females are significantly less likely to make the statement (\(p < 0.05\)).

Result 1—selection Individuals who voluntarily decide to make the cooperation statement, contributed already before the pledge on higher levels to the public good than individuals who decided against the voluntary pledge.

Our main interest was whether in addition to this selection effect, Statement-Makers changed their behavior. Comparing the coefficients for Stage 2, it becomes evident that the Statement-Makers indeed significantly increased their average contributions (\(p=0.002\)) after the pledge. Non-Takers, on the contrary, do not show a significant change in their contribution behavior. Thus, we find support for Hypothesis 2, making the statement prompts a change in behavior.

Result 2a—behavioral change Voluntary Statement-Makers increase their contributions after they made the cooperation statement.

Model 3 tests the robustness of the result and considers as additional explanatory variables the average contribution level of other players, which the individual players experienced in Stage 1, and which, as the coefficient \(OthersContrib\_S1\) shows, positively influenced their contributions. The significant change in the contribution behavior of Statement-Makers persists.

Model 4 controls in addition for the number of other players who (also) made a statement in one’s matching group (\(N\_ State\_others\)). As it has previously been argued, the associated coordination makes up part of the observed behavioral change in the Voluntary treatment group. Now that we control for the number of Statement-Makers, the influence of Voluntary is hence smaller and weaker (\(p=0.07\)). The aforementioned difference between the change in behavior of voluntary Statement-Makers and Non-Takers remains (\(F=3.86\), \(p=0.05\)).

To gain a better understanding of the drivers for the behavioral change, we examine how beliefs changed in correspondence to the statement. Table 4 displays (i) the expectations from other players, (ii) players’ own second-order beliefs and (iii) the respective contributions. To measure the pure effect of the statement in regard to others’ expectations, we focus on the beliefs and contributions only from the first round of the second stage. This was the first interaction after a new group was formed and players were not yet able to predict the other players’ behavior based on previous interactions.

Expectations in the Voluntary treatment group were significantly higher than the expectations subjects formed in the Control group. Interestingly, this was not only the case for the expectations toward the Statement-Makers (Mann–Whitney U test (MWU): \(Z = -4.114\), \(p < 0.01\)), but also for the expectations toward the Non-Takers (MWU: \(Z = -2.043\), \(p = 0.041\)). In general, the introduction of the statement made subjects more optimistic of what contributions to expect in the second stage. But within these optimistic beliefs, expectations toward Statement-Makers were higher (MWU: \(Z = -1.797\), \(p = 0.072\)).Footnote 7 The second-order beliefs, in contrast, were only higher for the Statement-Makers, they anticipated correctly that other players expected significantly higher contributions from them (Non-Takers vs. Statement-Makers—MWU: \(Z= -5.572\), \(p< 0.001\)). This is in line with previous research on expectation-based guilt aversion in bilateral interactions (Charness and Dufwenberg 2006, 2010). Statement-Makers knew that they raised the expectations of others (second-order beliefs) and feared feeling guilty if they would not meet these expectations. However, it needs to be mentioned that with our design we are not able to rule out that Statement-Makers reported higher second-order beliefs simply to be consistent with the higher contributions made.

3.2 Voluntary versus compulsory statements

In this section, we compare the behavioral changes of the Voluntary treatment group with the Compulsory condition in which all group members had to make the statement. In the hypotheses, we argued that the intrinsic commitment associated with a compulsory pledge should be weaker and also less credible, since everyone knows that the pledge was forced. Our data, however, show that the compulsory nature of the pledge does not mean that the statement had less impact on subsequent behavior.

To assess the difference between the Voluntary and Compulsory statement, Fig. 2 plots the dynamic developments of the average contribution in the Control group as well as in the two treatment groups. Panel A shows the dynamic development of average contributions in each group, Panel B depicts the fitted values of the differences in contributions between Stage 1 and 2 (based on the following regression analyses). Contributions in public good games typically decline, but as Fig. 2 suggests, contributions in the Voluntary treatment group declined faster than in the Control and Compulsory treatment group. As one can see on the lower right, the decline seems to be caused by participants who made the statement voluntarily, they reduced their initial high contributions significantly over time.

Table 5 presents the corresponding regression results estimating the change in individual contributions between Stage 1 and Stage 2 for each round. Model 4 examines the data at the aggregate level. The coefficients Voluntary and Compulsory, which measure the average difference in contributions between Stage 1 and 2, show that average contributions increased significantly not only in the Voluntary treatment group but also in the Compulsory treatment group. Thus, we find support for Hypothesis 2 also in case of the compulsory statements.

Result 2b—behavioral change Individuals for whom the pledge of the cooperation statement was compulsory also increased their contributions compared to previous levels.

Model 5 then distinguishes between Statement-Makers and Non-Takers for the Voluntary treatment group. The lower right side of Fig. 2 is based on this estimation. The coefficients \(Voluntary \times State\) and Compulsory estimate for voluntary and compulsory Statement-Makers the change between Stage 1 and 2 contributions at the beginning of Stage 2. We find that the two coefficients differ in a statistically significant way (\(Chi2(1) = 4.17\), \(p=0.041\)), voluntary statements induced a stronger commitment at first. However, as interactions progressed, the improvement vanishes and contributions deteriorated faster than when the statements were compulsory (H0: Voluntary \(\times \) State \(\times \) Round = Compulsory \(\times \) Round: \(Chi2(1) = 3.02\), \(p=0.082\)). The results remain robust when individuals’ average contribution levels in Stage 1 are taken into account (\(AvgContrib\_S1\) - Model 6). We therefore find partial support for Hypothesis 3.

Result 3 At first, the voluntary statement leads to a higher increase in contributions than the compulsory statement.

Result 4 Over time, the positive effect of the voluntary statements wore off faster than when the statements were compulsory.

The reduction may be explained with conditional cooperation. After the first round, all subjects learned how much the other players in their group contributed, and voluntary Statement-Makers may have realized that the other group members, including Non-Takers, contributed less to the public good than they did. In response, they adjusted their contribution behavior and the good intentions of contributing 15 ECUs or more vanished. In the Compulsory group, on the other hand, the statement was made by everyone and this seems to have provided assurance about how the others would behave. In the beliefs, this positive coordinating effect is reflected. Already in the first round after the pledge, when the beliefs were not yet influenced by interaction, expectations in the Compulsory treatment group (15.07 ECUs) were significantly higher than in the Voluntary treatment group (11.25 ECUs – MWU: \(Z=-6.713\) \(p<0.01\)), but also higher than the expectations toward only the voluntary Statement-Makers (12 ECUs – MWU: \(Z = -4.99\), \(p < 0.01\)). Over the course of Stage 2, the difference in first-order expectations between the two treatment groups prevailed (MWU: \(Z = -3.910\), \(p<0.01\)).

The comparison between the Voluntary and Compulsory treatment group suggests that improved coordination seems to have been a key driver for the improved contribution behavior after the pledge. Groups in which all four players voluntarily chose to make the statement can provide insights into the combined effect of strong coordination and autonomous choice. In our sample, this was only the case in two experimental groups and consequently the following analysis must be taken as highly indicative due to the low observation numbers. In these two groups, average contribution levels in Stage 2 (17.43 ECUs (sd: 2.65)) as well as the average difference in individual contribution levels between Stage 1 and Stage 2 (\(+5.15\) ECUS (sd: 1.47)) were significantly higher than in all other groups (average increase in the other groups of Voluntary: 1.27 ECUs (sd: 4.20), and Compulsory 2.52 ECUs (sd: 6.49)). A graph with the respective contributions can be found in the Appendix. While the high contribution levels can be explained by selection, the large increase in contributions suggests that the strong coordination component paired with self-driven commitment was a powerful combination to boost contributions.

Finally, subjects’ compliance with the statement shall be discussed. In the first round of Stage 2, both groups of Statement-Makers, voluntary and compulsory, were with their contributions close to the stated level (voluntary Statement-Makers: 14.39 ECUS (sd: 5.02) and compulsory Statement-Makers: 14.80 ECUs (sd: 5.27)). The compliance rates of 87% for the Voluntary Statement-Makers and 83% for the compulsory Statement-Makers were not statistically different (prtest: \(Z=0.537\), \(p=0.591\)). However, over the course of Stage 2 the compliance deteriorated, resulting in an average compliance of 68% for the voluntary and 73% for the compulsory Statement-Makers. Overall, compulsory Statement-Makers were thus slightly more often compliant than voluntary Statement-Makers (prtest: \(Z=-1.671\) \(p=0.095\)). We believe that this is also due to the fact that Statement-Makers lost their motivation to fulfill the statement more quickly when they played in the Voluntary treatment group with Non-Takers. The two groups, in which all group members voluntarily chose to make the statement, met in all rounds, except in the last two, the required contribution level. This finding points again to the benefits of improved coordination when everyone makes the statement.

4 Conclusion

Our results suggest that public cooperation statements can help promote pro-social behavior in public good settings, even if the pledge is only in the form of a public consent with a given statement. In practice, we find such consent schemes with cooperation statements, for example, in professional codes of conducts.

Based on our within-subject design, we were able to show that individuals get, in contrast to rational choice predictions, affected by the pledge and that the behavioral effects are not only due to selection. Making a cooperation statement leads to an increase in pro-social behavior. Furthermore, we argued that this behavioral change has two drivers, first, the self-driven commitment to fulfill the pledge, and second, the benefit of improved coordination between the interaction partners. In contrast to findings from bilateral interactions, we show that in social dilemma situations compulsory cooperation statements are not less effective in promoting cooperation than voluntary statements. On the contrary, they may even work better when the general willingness to make a voluntary pledge is low.

To what extent are these results specific to the artificial situation in an experimental laboratory and what conclusions can be drawn for the real world? In our experiment, it was clearly defined what was considered a contribution to the public good and which behavior resembled compliance with the pledge. In real-world settings, this is rarely the case. Sometimes deviations can be easily identified, but in most cases, the distinction between violating against the promised cooperation and simply acting in a less socially acceptable way is blurred. Hence, the abstraction in our experiment naturally impairs the external validity of our findings. However, the purity of incentives and the clarity of the decision setting allowed us to identify two drivers that motivate behavioral change when public cooperation statements are used—intrinsic commitment to the promised behavior and improved coordination between the interaction partners. For future research, it would be interesting to probe the workings of these two drivers in the field.

In general, our research suggests that public cooperation statements, although not binding, can help to promote pro-social behavior in social dilemma situations. Compared to legally binding rules and open discussion forums, public consent with pre-defined statements may be a solution that is simpler and less costly to implement and yet promotes contributions to the public good.

Notes

The communication in Dannenberg’s study was based only on the numerical announcement of the intended contribution level and the message was not in text format. Compared to Koukoumelis finding, this may have curtailed the message’s credibility.

The rematching of players was done in a way that none of the players interacted twice. With 16 participants per session, a perfect stranger matching was guaranteed and this was common knowledge.

Subjects who decided not to pledge had to key in a neutral text: “I am a voluntary participant in this experiment, no coercion or interference has taken place.” This text was already introduced in the baseline stage and was of similar length as the contribution statement.

Respective screenshots and instructions can be found in the Appendix.

Croson and Marks (2001) find that feedback about single players’ contribution compared to information about the total contribution does not change the average contributions. Also, Fehr and Gächter (2000) do not find a difference in contributions when feedback is provided at an aggregate level or by showing the entire contribution vector.

As one reviewer pointed out, it is possible that sophisticated low contributors may disguise themselves and use the pledge to motivate their new group members to high contributions. In our experiment, however, this strategic motive seems to play a subordinate role; as we will see later in the results section, previous high contributions are a valid predictor for statement-making.

When the analysis is based on the beliefs from all Stage 2 rounds, the divergence among these expectations becomes stronger.

To have an indication how religious participants were, we asked “Apart from weddings, funerals and christenings, how often do you attend religious services these days?” The variable was coded with “More than once a week” (1), “Once a week” (2), “Once a month” (3), “Once a year” (4), “Less often than once a year” (5), “Never” (6). The observed average of 4.43 suggests that participants on average went to church once per year or less; apart from weddings, funerals and christenings.

We asked the following questions: (1) How important is it for people to keep promises, if they can, to friends? (2) How important is it for people to keep promises, if they can, even to someone they hardly know? (3) How important is it for parents to keep promises, if they can, to their children? (4) How important is it for people to tell the truth? The variable was coded in reverse order: very important (1), important (2), not important (3). Thus, a high score in SRM indicates that the person stated that he or she perceives promise-keeping as less important.

The original version includes 50 items, we used a shorter version from Fischer and Fick (2003) which is proofed to be also valid and internally consistent (Barger 2002).

References

Balliet D (2009) Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analytic review. J Confl Resolut 54(1):39–57

Barger SD (2002) The Marlowe–Crowne affair: short forms, psychometric structure, and social desirability. J Personal Assess 79(2):286–305

Basinger KS, Gibbs JC (1987) Validation if the social moral reflection objective measure—a short form. Psychol Rep 61(1):139–146

Battigalli P, Charness G, Dufwenberg M (2013) Deception: the role of guilt. J Econ Behav Organ 93:227–232

Beck T, Bühren C, Frank B, Khachatryan E (2020) Can honesty oaths, peer interaction, or monitoring mitigate lying? J Bus Ethics 163(3):467–484

Belot M, Bhaskar V, van de Ven J (2010) Promises and cooperation: evidence from a TV game show. J Econ Behav Organ 73(3):396–405

Bicchieri C, Lev-On A (2007) Computer-mediated communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: an experimental analysis. Politics Philos Econ 6(2):139–168

Binmore K (2006) Why do people cooperate? Politics Philos Econ 5(1):81–96

Bochet O, Page T, Putterman L (2006) Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. J Econ Behav Organ 60(1):11–26

Carlsson F, Kataria M, Krupnick A, Lampi E, Lfgren SA, Qin P, SternerSterner T (2013) The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth a multiple country test of an oath script. J Econ Behav Organ 89:105–121

Charness G, Dufwenberg M (2006) Promises and partnership. Econometrica 74(6):1579–1601

Charness G, Dufwenberg M (2010) Bare promises: an experiment. Econ Lett 107(2):281–283

Chaudhuri A (2011) Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Exp Econ 14(1):47–83

Conrads J, Reggiani T (2017) The effect of communication channels on promise-making and promise-keeping: experimental evidence. J Econ Interact Coord 12(3):595–611

Croson R, Marks M (2001) The effect of recommended contributions in the voluntary provision of public goods. Econ Inq 39(2):238

Dannenberg A (2015) Leading by example versus leading by words in voluntary contribution experiments. Soc Choice Welf 44(1):71–85

Di Bartolomeo G, Dufwenberg M, Papa S, Passarelli F (2019) Promises, expectations & causation. Games Econ Behav 113:137–146

Ederer F, Stremitzer A (2017) Promises and expectations. Games Econ Behav 106:161–178

Ellingsen T, Johannesson M (2004) Promises, threats and fairness. Econ J 114(495):397–420

Fehr E, Gächter S (2000) Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am Econ Rev 90(4):980–994

Festinger L (1957) A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Fischbacher U, Gächter S, Fehr E (2001) Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ Lett 71(3):397–404

Fischer D, Fick C (1993) Measuring social desirability: short forms of the Marlowe–Crowne social desirability scale. Educ Psychol Meas 53(2):417–424

Frederick S (2005) Cognitive reflection and decision making. J Econ Perspect 19(4):25–42

Gibbs JC, Basinger KS, Fuller D, Fuller RL et al (2013) Moral maturity: measuring the development of sociomoral reflection. Routledge, Milton Park

Gneezy U (2005) Deception: the role of consequences. Am Econ Rev 95(1):384–394

Greiner B (2015) Subject pool recruitment procedures: organizing experiments with orsee. J Econ Sci Assoc 1(1):114–125

Hergueux J, Jacquemet N, Luchini S, Shogren J (2016) Leveraging the honor code: public goods contributions under oath. Technical report, HAL

Hurkens S, Kartik N (2009) Would I lie to you? On social preferences and lying aversion. Exp Econ 12(2):180–192

Jacquemet N, Joule R-V, Luchini S, Shogren JF (2013) Preference elicitation under oath. J Environ Econ Manag 65(1):110–132

Jacquemet N, Luchini S, Rosaz J, Shogren JF (2019) Truth telling under oath. Manag Sci 65(1):426–438

Jacquemet N, Luchini S, Shogren JF, Zylbersztejn A (2018) Coordination with communication under oath. Exp Econ 21(3):627–649

Joule R, Beauvois J (1998) The free will compliance: How to get people to freely do what they have to do. PUF, Paris

Kerr NL, Kaufman-Gilliland CM (1994) Communication, commitment, and cooperation in social dilemma. J Personal Soc Psychol 66(3):513

Kiesler CA (1971) The psychology of commitment: experiments linking behavior to belief. Academic Press, New York

Koessler A-K (2019) Setting new behavioral standards: sustainability pledges and how conformity impacts their outreach. Available at SSRN 3369557

Koessler A-K, Torgler B, Feld LP, Frey BS (2019) Commitment to pay taxes: results from field and laboratory experiments. Eur Econ Rev 115:78–98

Koukoumelis A, Levati MV, Weisser J (2012) Leading by words: a voluntary contribution experiment with one-way communication. J Econ Behav Organ 81(2):379–390

Ledyard JO (1995) Public goods: a survey of experimental research. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Linder DE, Cooper J, Jones EE (1967) Decision freedom as a determinant of the role of incentive magnitude in attitude change. J Personal Soc Psychol 6(3):245

Lundquist T, Ellingsen T, Gribbe E, Johannesson M (2009) The aversion to lying. J Econ Behav Organ 70(1):81–92

Mazar N, Amir O, Ariely D (2008) The dishonesty of honest people: a theory of self-concept maintenance. J Market Res 45(6):633–644

Messick DM, Wilke H, Brewer MB, Kramer RM, Zemke PE, Lui L (1983) Individual adaptations and structural change as solutions to social dilemmas. J Personal Soc Psychol 44(2):294–309

Ostrom E, Walker J, Gardner R (1992) Covenants with and without a sword: self-governance is possible. Am Political Sci Rev 86(02):404–417

Sally D (1995) Conversation and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analysis of experiments from 1958 to 1992. Ration Soc 7(1):58–92

Schaffner M (2013) Programming for experimental economics: introducing CORAL—a lightweight framework for experimental economic experiments. QuBE Working Papers 016, QUT Business School, Brisbane, Australia

Schlesinger HJ (2011) Promises, oaths, and vows: on the psychology of promising. Taylor & Francis, Milton Park

Vanberg C (2008) Why do people keep their promises? An experimental test of two explanations. Econometrica 76(6):1467–1480

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Uri Gneezy, Nicholas Jaquemet, Richard Jefferson, Sarah Necker, Pedro Rey-Biel, Benno Torgler, Caroline van Bers and Israel Waichman for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper. The authors would also like to express their special thanks to two anonymous reviewers whose constructive feedback has contributed to improving the quality of this manuscript. Ann-Kathrin Koessler thanks the QUT Business School for the funding of the experiments and the Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation for the support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Subject pool

1.2 Contributions of groups with \(n=4\) statement-makers

1.3 Demographic characteristics of statement-makers

In the following, we shed light on the characteristics of subjects who voluntarily made the statement in the Voluntary treatment group. For this purpose, we use demographic data and information from psychological measures we elicited in a post-experimental questionnaire. We asked subjects for their sex, age, degree, course and religiosity.Footnote 8 We also asked five questions from the Socio-moral Reflection Measure Questionnaire (Basinger and Gibbs 1987; Gibbs et al. 2013), which address socio-moral values like truth-telling. The selected questions asked for participant’s attitude toward promises and lying.Footnote 9 We also elicited a short version of the Crowne and Marlow Social Desirability Scale (SDS). This scale is often used in Psychology and Clinical Research to measure the need for social approval.Footnote 10 A person with a high SDS score is more likely to perform certain behavior due to a desire to be socially accepted or approved. Ultimately, as an estimator for strategic reasoning, we integrated the cognitive reflection test (CRT) (Frederick 2005). This test is designed to assess an individual’s ability to suppress an intuitive response, which is incorrect, and engage in further reflections that lead to the correct response. Answers were incentive compatible so that participants were paid 1 AUD for each correct answer. The CRT measure ranges from 0 to 3, indicating a person with a high CRT score is able to resist intuitively compelling responses.

Table 8 shows the likelihood that a participant takes the statement voluntarily in Stage 2 based on the demographic characteristics. Model 1 takes into account a participant’s study major and degree, gender and age as well as the experience with economic experiments. The variables Female, Econ and Postgraduate are dummy variables which take the value one when the participant was, respectively, female, studied Economics or enrolled in a postgraduate course. Model 2 predicts the likelihood of making the voluntary statement based on the extent to which a participant was satisfied with his or her financial situation and the degree of religiosity. Model 3 uses the psychological measurements we elicited in the experiment as explanatory variables. Model 4 combines all previous three models and Model 5 controls additionally for the experience a participant has made in the previous stage (average contribution of the other group members in Stage 1) and the own contribution behavior in Stage 1. The results show that only own contribution behavior in Stage 1 and gender have a significant and robust impact on the decision to voluntarily make a cooperation statement. When a participant was female, she was 40% less likely to make the voluntary statement (\(p=0.016\) in Model 5).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koessler, AK., Page, L. & Dulleck, U. Public cooperation statements. J Econ Interact Coord 16, 747–767 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-021-00327-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-021-00327-4