Abstract

In modern organizations, new communication channels are reshaping the way in which people get in touch, interact and cooperate. This paper, adopting an experimental economics framework, investigates the effect of different communication channels on promise-making and promise-keeping in an organizational context. Inspired by Ellingsen and Johannesson (Econ J 114:397–420, 2004), five experimental treatments differ with respect to the communication channel employed to solicit a promise of cooperation, i.e., face-to-face, phone call, chat room, and two different sorts of computer-mediated communication. The more direct and synchronous (face-to-face, phone, chat room) the interpersonal interaction is, the higher the propensity of an agent to make a promise. Treatment effects, however, vanish if we then look at the actual promise-keeping rates across treatments, as more indirect channels (computer-mediated) do not perform statistically worse than the direct and synchronous channels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Balliet (2010) provides a meta study on the effects of communication on social dilemmas. The author finds large positive effects of communication on cooperation, which is moderated by the type of communication, i.e., face-to-face communication has a stronger effect compared to written messages.

This treatment reproduces either a freelance working relationship or interaction with a colleague within the firm who is located in an overseas office.

The topic of the survey was about the individual perception of different NGOs in terms of trust and reputation. The content of the survey was not announced during the promise-making phase.

Like in the PC-Lab treatment subjects (i) first engage in the unrelated task, (ii) the outcome/payment is communicated, and finally (iii) the promise-making task is administrated.

This is a key technical feature of the “elfe” laboratory of the University of Duisburg-Essen. For this reason this venue is well suited to host studies focusing on communication channels.

In treatment PC-Online, subjects were informed that they would receive an email containing an URL link to get to the survey platform (see Script. A.1 in the “Appendix”). In this case, the following wording was adopted “[...] If you promise to participate, within 5 min you will receive a voucher via email with the link to access to the survey”.

Note that the same female research assistant (24 years old) was intentionally chosen to communicate with the subjects because the experimenters, males and above the age of a typical university student, might bias subjects’ actions due to obedience or authority concerns; see Karakostas and Zizzo (2016). During the experimental sessions the subjects did not encounter any other research assistants or experimenters. In order to control for gender-related effects (Solnick and Schweitzer 1999; Eckel and Grossman 2001), in each treatment almost 1/2 of the subjects were males and 1/2 were females (see Table A.4).

The sender was the academic society HEIRS—Happiness, Economics and Interpersonal Relations; University of Milan-Bicocca < http://www.heirs.it/ \({>}{<}\) info@heirs.it \({>}\). This scientific society has no connection with the University of Duisburg-Essen. The subject of the email was: “online survey access link.”

In order to minimize subjects’ transaction costs, we provided shortened URLs (e.g., http://goo.gl/s3aCrd) that are quick and easy to type in all different internet browsers. This is also to keep the setting as constant as possible compared to the PC-Online treatment, where subjects received an already active URL link in the body of the emailed voucher, and they just needed to click on it in order to get access to the survey (see Script A.1). Table A.5 reports how the promptness in fulfilling the promise was not different under the alternative experimental conditions. In all the treatments, subjects took on average 6 h and 30 min before filling the survey. This result provides evidence about the fact that receiving an already “active link” (PC-Online treatment) does not represent and advantage in terms of promise-keeping.

We monitored the activity on the online survey platform both before and after the provided 24 h time window. No one visited the survey platform before the actual start (1 h buffer time after promise-making). The survey platform was monitored during the subsequent 2 days, no one filled in the survey after the deadline.

We thank an anonymous referee for his/her advice on this point.

See Frank (1988).

The Jonckheere–Terpstra test is a non-parametric test for more than two independent samples, similar to the Kruskal–Wallis test. Unlike Kruskal–Wallis, Jonckheere–Terpstra tests for ordered differences between treatments, and hence it requires an ordinal ranking of the test variable. For a more detailed description of the test, see Hollander et al. (2015).

The coefficients for PC-Lab and PC-Online (both asynchronous channels) turn to be not statistically different from each other (Wald-test \(p=0.509\)).

It is the number of reported tails in the coin flip task by Conrads and Lotz (2015). In this experimental task, subjects had to privately flip a coin four times. Each time tails was reported, a subject earned 1 Euro in addition to a fixed payment of 7 Euros for filling in a socio-demographic questionnaire. Thus, subjects had an incentive to over-report the true outcome of the four coin flips. The independent variable labeled ‘Reported outcome’ in Tables 3 and A.5 captures the payoffs earned by subjects in the previous experimental task (this control variable varies between 0 and 4). ‘Reported outcome’ can be interpreted both as behavioral outcome and, as a consequence, payoff earned in Conrads and Lotz (2015) task, e.g., if a subject reported tails four times she would also earn 4 Euros.

We thank an anonymous referee for this remark (see also Footnote 11).

No subject started the survey without fully completing it. No one accessed the survey platform before the starting time or after the deadline.

References

Ai C, Norton E (2003) Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ Lett 80(1):123–129

Balliet D (2010) Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analytic review. J Confl Resolut 54(1):39–57

Ben-Ner A, Putterman L, Ren T (2011) Lavish returns on cheap talk: two-way communication in trust games. J Soc Econ 40(1):1–13

Berger J, Herbertz C, Sliwka D (2011) Incentives and cooperation in firms: field evidence. Discussion paper, IZA—Discussion Paper No 5618

Bicchieri C, Lev-On A (2007) Computer-mediated communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: an experimental analysis. Polit Philos Econ 6(2):139–168

Bochet O, Page T, Putterman L (2006) Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. J Econ Behav Org 60(1):11–26

Bohnet I, Frey BS (1999) Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games: comment. Am Econ Rev 89(1):335–339

Branas Garza P (2007) Promoting helping behavior with framing in dictator games. J Econ Psychol 28(4):477–486

Brosig J, Weimann J, Ockenfels A (2003) The effect of communication media on cooperation. Ger Econ Rev 4(2):217–241

Charness G, Dufwenberg M (2006) Promises and partnership. Econometrica 74(6):1579–1601

Charness G, Dufwenberg M (2010) Bare promises: an experiment. Econ Lett 107(2):281–283

Charness G, Gneezy U (2008) What’s in a name? Anonymity and social distance in dictator and ultimatum games. J Econ Behav Org 68(1):29–35

Conrads J, Lotz S (2015) The effect of communication channels on dishonest behavior. J Behav Exp Econ 58:88–93

Eckel C, Grossman P (2001) Chivalry and solidarity in ultimatum games. Econ Inq 39(2):171–188

Ellingsen T, Johannesson M (2004) Promises, threats and fairness. Econ J 114:397–420

Frank RH (1988) Passions within reason: the strategic role of the emotions. WW Norton & Co, New York

Gaechter S, Fehr E (1999) Collective action as a social exchange. J Econ Behav Org 39(4):341–369

Greene W (2010) Testing hypotheses about interaction terms in nonlinear models. Econ Lett 107(2):291–296

Greiner B (2015) Subject pool recruitment procedures: organizing experiments with ORSEE. J Econ Sci Assoc 1(1):114–125

Haidt J (2001) The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol Rev 108(4):814–834

Hancock JT, Thom-Santelli J, Ritchie T (2004) Deception and design: the impact of communication technology on lying behavior. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. ACM, pp 129–134

Harbring C (2006) The effect of communication in incentive systems: an experimental study. Manag Decis Econ 27:333–353

Hoffman E, McCabe K, Smith VL (1996) Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games. Am Econ Rev 86(3):653–660

Hollander M, Wolfe D, Chicken E (2015) Nonparametric statistical methods. Wiley, New York

Karakostas A, Zizzo D (2016) Compliance and the power of authority. J Econ Behav Org 124:67–80

List J, Shaikh A, Xu Y (2016) Multiple hypothesis testing in experimental economics. Discussion paper, National Bureau of Economic Research—WP 21875

Ma Q, Meng L, Shen Q (2015) You have my word: reciprocity expectation modulates feedback-related negativity in the trust game. PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119129

Roth A (1995) Bargaining experiments. In: Kagel JH, Roth AE, Hey JD (eds) The handbook of experimental economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 501–585

Schram A, Charness G (2015) Inducing social norms in laboratory allocation choices. Manag Sci 61(7):1531–1546

Seithe M (2010) Introducing the bonn experiment system. Discussion paper, Discussion paper. Graduate School of Economics, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany http://boxs.uni-bonn.de/boxs.pdf

Solnick S, Schweitzer M (1999) The influence of physical attractiveness and gender on ultimatum game decisions. Org Behav Hum Decis Process 79(3):199–215

The Economist (2016a) The collaboration curse. http://www.economist.com/news/business/21688872-fashion-making-employees-collaborate-has-gone-too-far-collaboration-curse. Accessed 15 June 2016

The Economist (2016b) The Slack generation. http://www.economist.com/news/business/21698659-how-workplace-messaging-could-replace-other-missives-slack-generation. Accessed 15 June 2016

Valley KL, Moag J, Bazerman MH (1998) A matter of trust: effects of communication on the effciency and distribution of outcomes. J Econ Behav Org 34:211–238

Vanberg C (2008) Why do people keep their promises? An experimental test of two explanations. Econometrica 76(6):1467–1480

Walther JB (2011) Theories of computer-mediated communication and interpersonal relations. In: Knapp ML, Daly JA (eds) The sage handbook of interpersonal communication. 4th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 443–479

Acknowledgments

We thank Katrin Recktenwald for excellent research assistantship; Michele Belot, Luigino Bruni, Giovanni Ferri, Bernd Irlenbusch, Patrick Kampkotter, Andrew Kinder, Pierluigi Murro, Rainer Michael Rilke, Matteo Rizzolli, Alessandro Saia, Rupert Sausgruber, Dirk Sliwka, Robert Slonim, Janna Ter Meer, Serena Trucchi, the Associate Editor and two anonymous referees for comments and valuable advice. Moreover, we thank Jeannette Brosig-Koch and Jan Siebert from the experimental laboratory ‘elfe’ at the University Duisburg-Essen for letting us run the experimental sessions. This research project is financially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through grant FOR 1371—University of Cologne “Design and Behavior: Economic Engineering of Firms and Markets.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

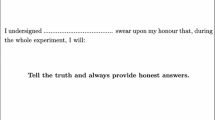

1.1 Script A.1 Voucher: Further instructions after making the promise to access to the online survey

Thank you very much that you agreed to participate in the online survey.

Within the next 24 hours

from MM/DD/YY , HH/MM to MM/DD/YY , HH/MM

you reach the survey platform by using the following link:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conrads, J., Reggiani, T. The effect of communication channels on promise-making and promise-keeping: experimental evidence. J Econ Interact Coord 12, 595–611 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-016-0177-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11403-016-0177-9