Abstract

Purpose

The effects of tourism extend beyond purely economic considerations; they also have an impact on both the environment and people. Development of tools and procedures that foster consensus among practitioners and enable the measurement and benchmarking of impacts are required for tourism managers to be able to work on lowering and mitigating the sector’s effects, while enhancing the positive benefits. In this study a methodological proposition to assess the social impacts of tourism packages is presented.

Aim and scope

This study adapts and tests for the first time a social evaluation technique, the Product Social Impact Assessment (PSIA) method, to assess the social implications of tourism products and services. It is iteratively tested on 9 tourism packages in Mediterranean Protected Areas. Numerous parties, including managers of protected areas and private tourism stakeholders, have engaged in this process at various stages, such as developing the packages or supplying the data required for the assessment.

Conclusions

The methodology tested appears appropriate to quantify and qualify the social impacts of tourism packages and is valid for enhancing the social performance since positive progress between the two testing faces was registered. This study is a step towards standardizing the social assessment of tourism packages following a Life Cycle Assessment approach, and future developments are needed to make the approach proposed in the paper adequate to assess the social impacts of the upstream and downstream components of the system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Despite the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic halted international travel and had a significant negative impact on the sector’s development with losses of USD 4.5 trillion and 62 million jobs, prior to the pandemic the tourism industry accounted for 10.4% of the global GDP and 10.6% of all jobs with an essentially constant growth trend over time (Organización Mundial del Turismo 2018; World Travel and Tourism Council 2021). As it is closely tied to other economic sectors, the tourism industry has also had an amplifying impact; it is predicted that for every direct job produced in tourism, an additional 1.5 jobs are indirectly created in other economic sectors (Organización Mundial del Turismo 2020). This information can help one understand the sector’s significance for global economic growth. This significance is especially clear in the most touristic regions, such as the Southern Mediterranean, which welcomes 19% of all visitors at a global scale (Scott and Gössling 2018) and where the travel and tourism sector accounts for up to 14.1% of GDP (World Travel and Tourism Council 2021).

Tourism not only generates financial gains, but it also has significant effects on the environment and society, the other two pillars of sustainability, just like any key economic activity (Gnanapala and Sandaruwani 2016; Arzoumanidis et al. 2021). It is estimated that the worldwide tourism sector accounts for a share of global water consumption of around 1% (Gössling 2013) and is responsible for an approximate 8% of the global CO2 emissions (Lenzen et al. 2018). In certain countries, like Spain, the GHG emissions from the tourism industry may make up as much as 10.6% of the emissions from the entire national economy (Cadarso et al. 2016). At the same time, the tourism industry is particularly sensitive to climate change since a destination’s appeal is typically influenced by specific environmental factors (Köberl et al. 2015).

Additionally, from a sociological standpoint, several groups of individuals may be impacted by tourism-related activities. It is commonly recognized that the tourism industry can influence employees’ wellbeing. Around 87% of tourism employment is low-skilled jobs with limited career opportunities, and most of its workforce is required at certain points of time as the tourism demand is highly seasonal mainly due to given climatic conditions that make destinations more attractive during particular periods (Kronenberg and Fuchs 2021). These realities have detrimental socioeconomic repercussions since they make it difficult for employees to find steady, well-paying jobs. Local populations may also notice the negative consequences of tourism and can experience impacts related with vandalism and crime but also with respect to the objectification of their place and the changes in traditional cultures and the host’s way of life (Cheer et al. 2019). The local community can also be negatively affected at an economic level as tourism can increase the demand for some products and services that can lead to price inflation thus overburdening the access of permanent residents (Higgins-Desbiolles et al. 2019). Other groups of people besides employees and inhabitants may also be impacted by tourism-related activities depending on the specifics of each place, such as the value chain of the industry, society at large and tourists themselves. If properly managed, tourism can bring positive benefits and enhance the quality of life of societies while taking advantage from it, as stakeholders play a fundamental function in the development of sustainable tourism (Muler Gonzalez et al. 2018). The upkeep and construction of infrastructure, the promotion of direct and indirect workforce development, the distribution of economic growth, the spread of environmental and cultural awareness and pride, the capacity building of individuals and groups, the improvement of public health and safety issues, etc. are all social opportunities that can result from tourism (Ramkissoon 2020).

If tourism pretends to be a resilient and sustainable industry, managers should develop tourism models that are in tune with the essence of the ecosystems and human systems where the activities are taking place (Sánchez del Río-Vázquez et al. 2019). To do so, it is imperative to apply appropriate measurement tools to quantify the level of sustainability and monitor the progress over time to support the development of policies and projects and to take informed decisions at all scales (Zagonari 2019; McLeod et al. 2021).

To tackle this challenge, the primary objective of this study is to establish a comprehensive framework for evaluating the positive and negative social impacts of tourism products and service providers. This involves adapting and testing the Product Social Impact Assessment (PSIA) method, which has not been previously applied in the context of tourism. Building upon existing research and relevant schemes, the study aims to refine and tailor certain aspects of the methodology to suit the unique characteristics of the tourism industry.

2 State-of-the art

Tourism has been included in internationally accepted standards and guidelines that aim to achieve sustainability, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that explicitly mention the sector in the SDG 8 “decent work and economic growth”, SDG12 “responsible consumption and production”, and SDG14 “the sustainable use of oceans and marine resources”. Additionally, there are various indicators schemes that have tried to provide tools to monitor and measure the social aspects of tourism as The European Tourism Indicator System (ETIS) (European Commission 2016) that was launched with the aim of helping destinations to evaluate their sustainable tourism performance, by using a common comparable approach. The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) developed the GSTC Criteria (Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) 2016) that are a set of minimum undertakings shaped as more than a hundred indicators that any tourism organization should aspire to when considering sustainability in their practices. The World Tourism Organization (WTO) that has been promoting the use of tourism indicators since the early 1990s presented the Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations (ISDTD): A Guidebook (World Tourism Organization (WTO) 2004) that describes over 40 major tourism sustainability issues, and for each issue, indicators are suggested. Additionally, several EU-funded projects as CO-EVOLVE and MITOMED + have adapted and developed social indicators for tourism in the Mediterranean region with the goal of enhancing the sustainability responsibility in tourism by helping local and regional policymakers to monitor impacts.

On the other hand, one of the most accepted and used techniques for holistically assessing sustainability of products and services is life cycle assessment (LCA) (Ekener et al. 2016). Social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) is a younger field of research partially based on the ISO 14040 standard, not as widespread as environmental and economic LCA (Lobsiger-Kägi et al. 2018; Fürtner et al. 2021). It includes the four main steps specified in the LCA framework: goal and scope, life cycle inventory (LCI), life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) and interpretation, and also is an iterative procedure that enables to improve the performance over time. There are two main methodologies coping with S-LCA: the UNEP-SETAC Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations and the Product Social Impact Assessment (PSIA) method. Building upon these foundational broad methods, various authors have developed more specialized assessment methodologies for evaluating S-LCA, aiming to address specific areas where precisions was previously lacking (Ramirez et al. 2014). S-LCA is to be used to assess and compare the social characteristics of products and services, as well as their potential positive and negative effects throughout their life cycles (UNEP 2020). For the measurement of tourism environmental impacts, a life cycle thinking approach has been frequently applied in practical situations. However, with regard to S-LCA, there is a lack of case studies in tourism and, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, only Arcese et al. (2013) has considered a S-LCA approach in tourism to this day. Arcese et al. provides an interesting contribution regarding the identification of social topics and indicators to qualitatively assess an accommodation facility but lacks a measurement method to allow the translation of the qualitative data to quantitative results better aligning the proposed framework with an LCA mindset and also a system for benchmarking the outcomes for comparison and performance improvements is absent.

Existing tourism assessment strategies and projects have successfully identified the key social topics and indicators relevant to the sector at a destination level. However, they have often lacked a comprehensive scientific framework that enables evaluation, comparison and informed decision-making. This deficiency is particularly evident in several dimensions:

-

1.

Life cycle perimeters: Current literature primarily focuses on select stages of tourism products’ life cycles, omitting critical phases which could offer significant insights (upstream and downstream processes such as infrastructure construction, goods production, and waste management).

-

2.

Range of issues considered: Presently, there is a wide variability in the topics addressed, which leads to a fragmented understanding of what constitutes the social sustainability of tourism. This lack of standardization in topic selection likely results in the underrepresentation or complete omission of certain relevant issues.

-

3.

Insufficiency and representativeness of literature: The paucity of literature on the social assessment of tourism inherently limits its representativeness. The current body of research, especially in terms of detailed case studies, is insufficient to effectively capture the diverse and evolving social impacts across different temporal and geographical contexts.

-

4.

Methodological gaps: There is a need for a more unified and standardized methodology in assessing the social aspects of tourism services. The existing limited literature shows a diversity of approaches, which, while valuable, complicates the comparison of data.

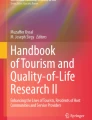

This paper aims to bridge this gap by integrating these previous advancements in social assessment of tourism into a S-LCA approach, specifically utilizing the PSIA method. Prior frameworks that focused on tourism sustainability assessment have laid the groundwork by identifying crucial social topics and developing relevant indicators. Building upon these foundations, the PSIA technique facilitates the creation of performance indicators that allow for result benchmarking, provide recommendations for improvement and transform qualitative insights into semiquantitative outcomes while enabling the comprehensive assessment of tourism packages from a life cycle perspective. Through this integration, illustrated in Fig. 1, it becomes possible to apply a systematic and standardized approach. This S-LCA procedure for tourism packages was tested and improved in 9 ecotourism packages located in various Mediterranean Protected Areas (PAs) as part of the EU-funded DESTIMED PLUS project.

3 Methodology

In the present study, the approach followed to assess the social impacts of tourism products is a bottom-up approach based on the PSIA method (Goedkoop et al. 2020), created by the Roundtable for Product Social Metrics project. The choice to utilize this strategy was made mostly due to the greater degree of development of the technique provided by PSIA regarding indicators and performance indicators, the applicability of the system for making recommendations, the possibility to address also positive impacts in addition to negative impacts and the clarity of the suggested outcomes visualization.

The information on the methodology developed to evaluate the social effect of tourism packages is further described in the following sections.

3.1 Goal and scope

The study’s primary goal is to develop and assess the effectiveness of a modified PSIA method tailored for evaluating the social impacts of tourism packages. Additionally, this assessment approach needs to be efficient for determining the effects as well as for offering suggestions for enhancing the social performance of the packages over time.

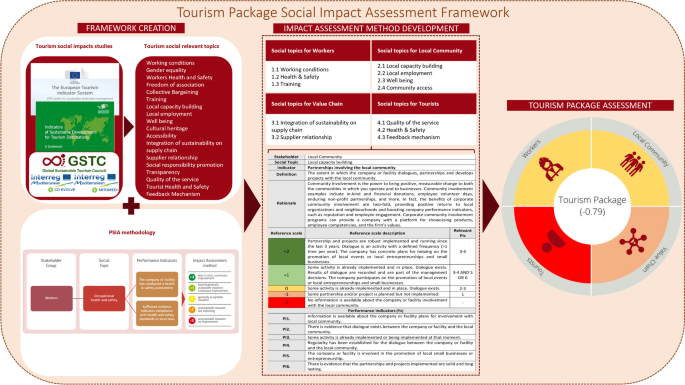

In relation with the goal of the study, only foreground processes in a gate-to-gate approach are considered in the assessment. The processes included in this S-LCA correspond to: (1) Accommodation, (2) Food&Drinks, (3) Mobility and (4) Activities&Services. This classification of services and activities is defined in accordance with the Ecological Footprint method for evaluating tourism packages developed by Mancini et al. (2018). From the system under study, the trip preparatory activities and the travelling to the destination and the return home are not considered in the assessment, as well as all the background processes (Fig. 2).

3.2 Data collection

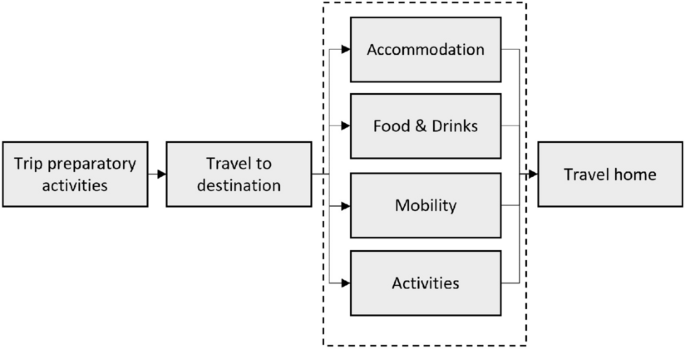

In the present study, company-specific data was collected from all the service providers of each tourism package by trained data collectors visiting the service providers’ sites. A scheme of the process is presented in Fig. 3. To do so, technical partners of the project provided training to the different Local Ecotourism Cluster (LEC) members to build capacity for a general understanding of the sustainability evaluation of the packages. Data collectors were specially trained to be able to engage data providers and collect the data needed to assess the social sustainability of the packages. Additionally, stakeholder involvement was essential, especially when specific data verification for each performance indicator was required. Despite the complexities introduced by the pandemic, concerted efforts to engage as much as possible the appropriate individuals for each piece of information were made. The unique aspect of ecotourism suppliers, typically small-scale businesses deeply rooted in their communities, was beneficial in gathering relevant data. The sensitivity of the data being collected presents its own set of challenges, necessitating careful and nuanced approach to ensure accuracy and reliability.

A social assessment data collection excel tool was developed by technical partners and validated by the LECs to facilitate the process of collecting data. This survey was distributed in each pilot site. The data collected is equivalent to the qualitative or quantitative answers for the performance indicators defined to assess each indicator that can be found in Table S2 of the Supplementary material 1. Additionally, a detailed document specifying the means of verification of the data provided for each performance indicator was handed to data collectors to ensure comparable results among pilot actions and can be consulted in the Supplementary material 2. After data was collected, the first step consisted of a validation process performed by the technical partners. Data was processed and evaluated in accordance with the developed social impact assessment approach once it was confirmed that each package included a complete and trustworthy dataset.

The data collection process took place twice for each tourism package since an iterative approach was considered for the S-LCA. After data was collected in an initial assessment round (R1), results were analysed in detail and based on that, recommendations for improvement of the social performance of each package were formulated and delivered to each concerned LEC and service provider. Time for the integration of the recommendation was given to managers of the different packages. Service providers implemented changes for improvement based on the list of suggestions and LECs, and in some occasions, also made decisions regarding the substitution of providers for new providers with better social performance or other quality-related reasons. After this refining phase, the second round of testing (R2) took place, and the tourism packages were assessed again following the same strategy, survey and set of indicators to prove the effectiveness of the undergone social impact assessment method on the upgrading of the tourism packages from a social performance perspective.

The PSIA methodology incorporates a data quality assessment matrix to evaluate and document the quality of data pertinent to the most critical life-cycle stages in tourism’s social assessment (Goedkoop et al. 2020). This matrix focuses on three primary criteria: data accuracy, timeliness or age and its correlation and representativeness. In this study, the data quality is assessed using the PSIA matrix. The data predominantly consists of non-verified internal data with documentation or verified data partially based on assumptions (assigned a score of 2), from the current reporting period (score 1) and specific to each site under study (score 1). This assessment yields an average data quality score of 1.3, which is notably close to the optimal score of 1 (where 1 signifies the highest quality and 5 the lowest).

3.3 Social impact assessment

In this phase, the data gathered in the inventory stage is translated into impacts or potential impacts. The PSIA methodology adopts a Type I approach, which indicates that the assessment methodology is based on performance reference points with the main purpose of drawing the picture of the actual social impacts of tourism packages. To translate the data collected into results, the key elements of the methodology, which are (i) stakeholder groups, (ii) social topics, (iii) indicators, (iv) performance indicators and (v) reference scale, should be defined.

Stakeholder groups

The first key components of the assessment are the stakeholder groups. Stakeholder groups are those groups of people whose interests could be potentially affected by the life cycle of a product or service. The social impacts of the tourism packages are assessed with regard to the identified stakeholder groups for the 4 categories of services and activities previously determined (Accommodation, Food&Drinks, Mobility and Activities&Services) thus avoiding the implementation of indicators that are not relevant for the specific system under study.

The stakeholder categories considered in the assessment of tourism packages are the 4 groups proposed in the PSIA methodology: Workers, Local Community, Value Chain and Customers. No other additional groups of people have been identified in the literature reviewed or the experts consulted to potentially be impacted by the tourism packages.

-

1.

Workers are those who operate in a specific industry to deliver a valuable product or service. Companies and facilities have a great influence on the overall Workers’ wellbeing, starting with remuneration but also in terms of working conditions and motivation. It is also important for companies that Workers are healthy, educated, satisfied and committed to be able to perform their tasks at an optimal level. Therefore, it is essential to safeguard and enhance the status of employees for both their benefit and the smooth operation of the business.

-

2.

Local Community reflects the group of people who can be indirectly impacted by a product which life cycle stages take place in the surroundings of the area they inhabit. It is important to have the acceptance and agreement of the community of the area in which an organization operates.

-

3.

The Value Chain stakeholder group is significant since its primary function is to provide high-quality components for the product or service in issue. Value Chain actors in this case refer to the suppliers providing food and beverages, linens and amenities, maintenance and repair, etc. to the accommodation, food, activities and transportation service providers of the tourism packages. Building solid relationships with suppliers based on satisfaction and trust is crucial.

-

4.

Customers, who in this case are the Tourists, are important since businesses rely on them to generate demand for their goods. Tourists may be impacted from several product-related viewpoints, including security and transparency as well as accessibility and pricing.

Social Topics, Indicators, Performance Indicators and Reference Scale

In relation to stakeholders, the social topics are the key social issues for each group of people that can be affected in a positive or negative way as a consequence of the development of one or more life cycle stages of the product or service. The most relevant socially significant aspects on which products and services can affect stakeholder groups need to be identified for each particular system, in our case a tourism package, by carrying out a materiality assessment. The prioritization of these most relevant aspects should not be based on intuition but using tools as literature, databases and stakeholders and experts’ consultation. In the present study, a first baseline of 19 social topics was created by crossing over and adapting the categories that the UNEP/SETAC Methodological Sheets and the PSIA Handbook propose with several tourism specific guidelines and studies (European Commission 2016; GSTC 2016; WTO 2004).

To assess the impacts of the tourism packages with regard to the different social topics identified for each stakeholder group, a set of indicators must be developed. Indicators can be qualitative, quantitative or semiquantitative and should be useful for judging in a consistent way the state of a specific condition. The construction or selection of these indicators cannot be made arbitrarily and should be adapted to the individual case without compromising the comparability of results. Even though there is no standardized method to do it, practitioners should be able to justify the procedural choices that brought them to a determined point. In this study, a multi-methodological iterative approach is adopted to identify, adapt and develop relevant indicators. In a first step, several generic S-LCA standards and tourism specific guidelines and past studies were consulted as the European Tourism Indicator System (ETIS), the Global Sustainable Tourism Council Criteria (GSTC), the Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations (ISDTD) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This initial screening allowed us to list 75 indicators that were adequate for addressing the different social topics. From this set of 75 indicators, the ones that were not measurable, practical or were overlapping in some respects with others were removed. This adjustment reduced the set of indicators to 45 indicators for 19 social topics that can be consulted in Table S1 of the Supplementary material 1. The DESTIMED PLUS project experts, comprising a diverse group of professionals from universities, regional authorities, PA agencies, international association, sustainability organizations, tourism institutes, service providers, data collectors and other key local stakeholders from the LEC, found the initial list of 45 indicators to be impractical, necessitating its reduction. The group’s key affiliations included the Government of Catalonia’s Department of Territory and Sustainability (Spain), Institute for Tourism (Croatia), Fundació Universitària Balmes (Spain), Development Agency for South Aegean Region Energeiaka S.A. (Greece), WWF Mediterranean (Italy), Corsican Tourist Agency (France), Autonomous Region of Sardinia — Department for Environment (Italy), IUCN Mediterranean Centre for Cooperation (Spain), Region of Crete (Greece), National Agency of Protected Areas (Albania), Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions of Europe (France), Regional Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fishing and Sustainable Development of Andalusia (Spain), Global Footprint Network (Italy) and Regione Lazio (Italy), among other local entities and individuals. To streamline the indicators, the experts participated in a survey, rating and commenting on each indicator. This process, guided by the survey results and practical considerations, resulted in a refined list of 16 indicators covering 12 topics (Table 1). The rationale for excluding certain indicators from the final selection is detailed in Table S2 of the Supplementary material 1.

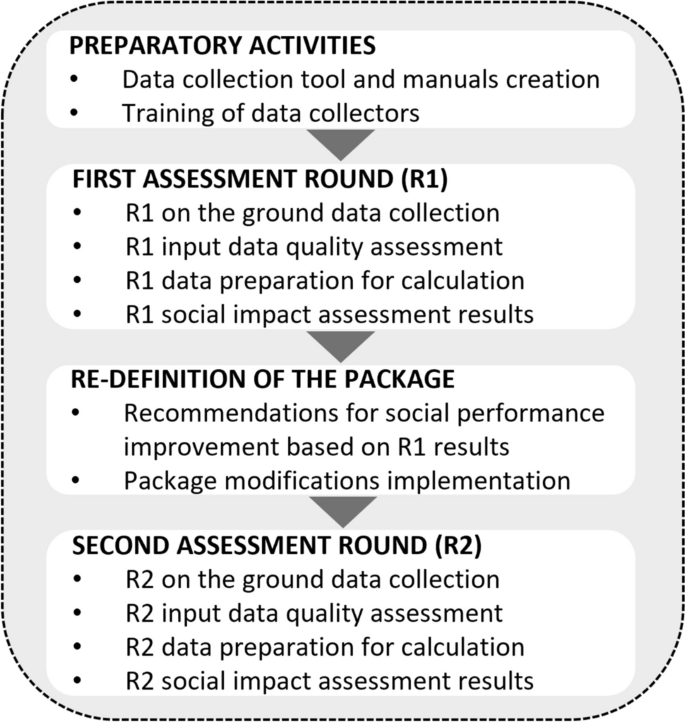

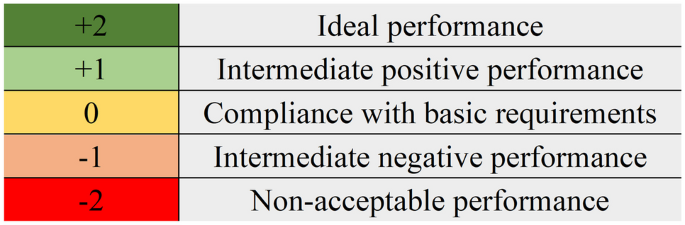

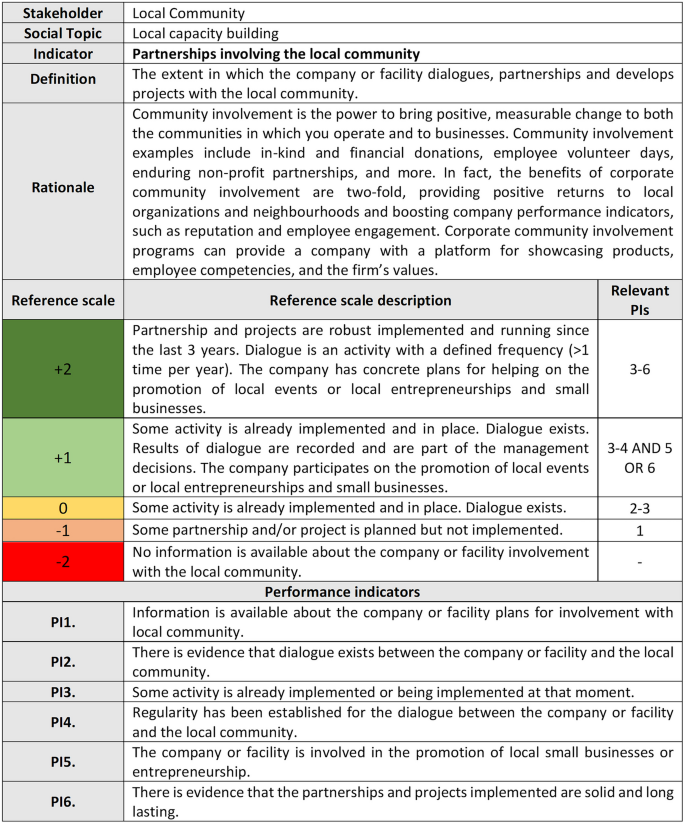

For each indicator, a properly defined reference scale is developed. Reference scales are necessary to interpret the results and estimate the significance of the social impacts associated with products and services. The PSIA methodology suggests a 5-point numeric scale that goes from − 2 to + 2, as can be seen in Fig. 4. Positive impacts are also considered in the assessment, so compliance beyond basic requirements is acknowledged and promoted. The meaning of each range of the scale should be clearly detailed for each indicator. Reference scales are constructed based on legislations, standards, non-binding guidelines and the sectors best in class and thought to be adaptable to each country’s regulations. For example, the reference scale for the indicator “% of jobs in tourism that are seasonal” that points < 15% of seasonality as an ideal performance and > 45% as a non-compliant performance is built based on data from the WTO for workers’ seasonality in European countries’ tourism sectors. The values chosen represent the second maximum and minimum seasonality % among the 10 countries for which information was available. Figure 5 shows the reference scale for the indicator “Partnerships involving the local community” as an illustration of a qualitative case and the reference scales for the rest of the indicators can be consulted in the Supplementary material 2. Simultaneously, a set of performance indicators is proposed for each indicator because of its usefulness to give a guideline on the type of data that needs to be collected to correctly assess each indicator and its support in determining the score achieved, from the reference scale, by the system under study. Not all indicators, especially those that are quantitative and the outcome is directly correlated with a score on the reference scale, require performance indicators to be appropriately evaluated. Performance indicators for qualitative indicators, as the ones presented as an example in Fig. 5, are created in this study, and the description of the 16 indicators’ reference scale and performance indicator can be consulted in Table S2 of the Supplementary material 1.

3.4 Results’ interpretation

For each tourism package, results are presented aggregated for confidentiality and practical reasons. Equation (i) calculates the arithmetic mean of each indicator scoring for each service provider. The variables n and m represent subsets of the total indicators and suppliers, respectively. Specifically, when calculating the average for all indicators and/or suppliers, n and m attain their maximum values. In any other scenario, the scoring will reflect a subset of the overall indicators or suppliers involved in the calculation. Weighting of indicators is completely avoided in this case study.

in which SC is the scoring, that corresponds to the arithmetic mean of each indicator for each service provider. Iij is the result of an indicator i for one service provider j. n is the number of indicators concerning each specific scoring aggregation. m is the number of service providers concerning each specific scoring aggregation.

3.5 Methodological limitations

The methodology developed, initially focused on eco-tourism service providers in the Mediterranean, has a notable limitation in its gate-to-gate analysis, overlooking broader upstream and downstream social impacts in areas such as transportation from origin to destination that can have social impacts as for example on the topic of community dynamics. Although this focus has allowed for detailed insights within this specific context, the methodology’s design inherently allows for adaptability to other tourism sectors and regions. Future enhancements are envisioned to tailor indicators to different local contexts and business types, thereby broadening its applicability. The methodology may not fully capture all stakeholder perspectives, for instance, in the case of indigenous populations and local inhabitants, while our indicators primarily focus on aspects related to the actions of service providers, such as partnerships, the local workforce, local suppliers and monitoring residents’ perceptions, we may be underrepresenting the direct perspectives of the local community. This highlights the need for more inclusive engagement of stakeholders in the topics and indicators selection and development in subsequent adaptations. In our attempt to provide a comprehensive set of topics and indicators, it is acknowledged that we may not have captured or addressed all relevant cause-and-effect mechanisms that can impact stakeholders, as for example aspects like supply chain transparency that require greater emphasis in future updates to provide a more comprehensive view of the social impacts of tourism.

Additionally, the nuances of real-life events are grossly oversimplified when using 5-point scales. The fact that the scales read − 1 and -2 as regular numbers presents a challenge. The logical deduction is that − 2 is twice as harmful as − 1; however, this is obviously not always the case. Additionally, when aggregating results, positive and negative values balance each other out leading to a neutralization. To address this, it is crucial to focus on a detailed interpretation of disaggregated results, with a particular emphasis on discussing extreme values that might otherwise be overlooked or masked.

4 Case study: the DESTIMED PLUS approach for ecotourism packages and its 9 protected areas

The methodology presented in this study is specifically designed to be applicable to a wide range of tourism products, considering in its boundaries general components of a package (Accommodation, Food&Drinks, Mobility and Activities), addressing overarching topics and stakeholder groups that are relevant to the global sector and using as a benchmark worldwide consensus concerning the direction that the tourism sector should take to guarantee a sustainable development. However, it has been tested in the framework of the DESTIMED PLUS project, a Mediterranean transnational cooperation project taking place from 2019 to 2022 that built on the findings of the EU-funded Interreg MED DESTIMED project and tested and evaluated a customized approach for the development, management, monitoring and promotion of ecotourism products in Mediterranean PAs. The primary difference between the DESTIMED and DESTIMED PLUS approaches in terms of the methodology is that the latter adds social and governance sustainability to the already existing set of environmental, conservation and quality considerations. Therefore, the establishment of a monitoring strategy and procedure to evaluate the social sustainability of the ecotourism packages is the main goal of this research.

In the context of this study, an ecotourism package or product is defined as a low-impact travel schedule that is customized to the area and its context, with specific activities and services planned day by day and delivered by local guides and suppliers. The DESTIMED PLUS project consolidated a system of 9 PAs in six Mediterranean countries, including Albania, Croatia, Greece, France, Italy and Spain, and engaged them in the establishment, design and monitoring of premium ecotourism packages in their respective regions. The formation of a LEC in each PA intended to serve as the central organization and was integrated by the PA management body, private stakeholder groups involved in local tourism and other stakeholders with an interest in tourism. The LECs facilitated the creation of packages through iterative and participatory processes.

Even though there is a large heterogeneity between packages because of the different geographical locations, there are some commonalities: the target market is an international tourist; the size of the group fluctuates around 10 people; the duration is 5–7 days and 4–6 nights, including conservation and local cultural activities; and all packages are designed to take place in shoulder season, the travel period between peak and off-peak seasons. Key facts of each package are described in Table 2.

5 Results and discussion

Tables 3 and 4 show the results, for the 2 testing rounds (R1 and R2), of the application of the social assessment approach proposed in this paper to the 9 tourism packages developed under the DESTIMED PLUS project. Considering that − 2 indicates the lowest performance, 0 represents a compliant performance, and + 2 signifies the highest performance; the results vary from − 0.84 to 1.25 in the first round (R1) and − 0.68 to 1.33 in the second round (R2). Notably, the highest performance in both rounds is achieved by La Garrotxa (Spain) tourism package. Out of 9 packages, 6 managed to improve the social performance between R1 and R2. The greater social performance improvement is achieved by the Porto Conte tourism package (− 0.07 in R1 to 0.45 in R2).

The following sections further discuss the results for all the packages with regard to the various social topics of each stakeholder group under study. The tourism packages show an overall average higher social performance for the Tourists stakeholder group and the lower social performance is found for the Value Chain, but an overall greater improvement between R1 and R2 of 0.17 is achieved for this last one. The average results regarding Workers and the Local Community fall between the compliant and intermediate positive performance for both testing rounds.

The results obtained from the social assessment of the tourism packages and the capacity to enhance the social performance through the process followed in this research are not only linked with the level of management that service providers execute but could also be associated with the endemic social and socio-economic issues that a region or a country faces. It is possible to discover some intriguing connections if we look closely at the outcomes of the assessment of the tourism packages in relation to the various topics under consideration and take the geographical component into account, so this subject has been also expanded upon in the suceeding lines.

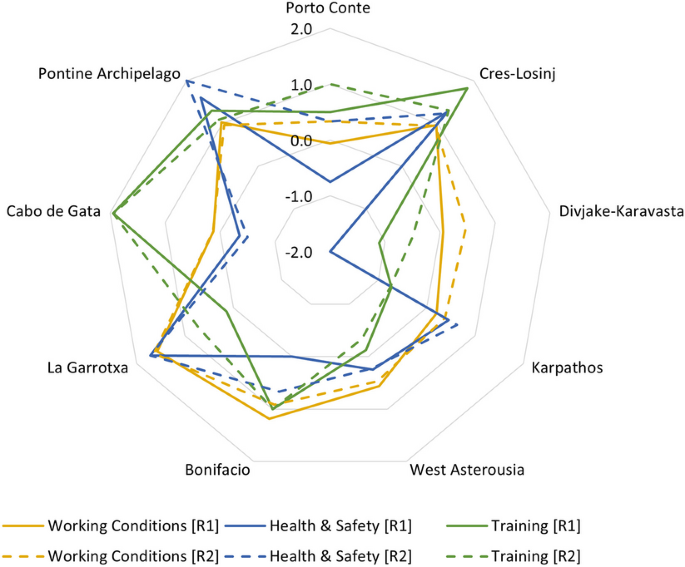

5.1 Workers

For the impacts on Workers, most of the packages are consistent with the standards or national average requirements and even are proactive in some cases. Overall results show an intermediate positive performance for Cres-Lošinj (Croatia), La Garrotxa (Spain), Bonifacio (France) and Pontine Archipelago (Italy) packages and a compliant behaviour for the others. Between the 2 testing rounds, significant improvements have been achieved by Porto Conte (Italy) and Divjake-Karavasta (Albania) packages. Among the three social topics corresponding to Workers, average results show a higher performance for the topic Working conditions, followed by the Training topic and lastly the Health&Safety topic. A general improvement of the social performance of the tourism packages is achieved for the three topics.

Concerning topics (Fig. 6), for Working conditions, all packages comply at least with the set basic requirements. La Garrotxa (Spain) stands out for its positive practices since it claims to have a plan in place to raise awareness and publicly report issues associated with forced and illegal labour, that the % of seasonal employers is less than 15%, and also that all Workers are paid better than the living wage in the country plus they receive additional social benefits on top of what is provided by the government. For the Pontine Archipelago (Italy) package, it is worth highlighting the positive performance regarding working time since they acknowledge that overtime is completely voluntary for Workers and prove to offer an economic compensation better than an ordinary hour or alternative compensation schemes per petition of the Worker (e.g. time-off). The Divjake-Karavasta package corrected the performance regarding working hours in R2 by proving that overtime does not exceed the maximum stipulated by law. Albania’s tourism sector has a deficient performance with regard to the average weekly working hours as the value (50 h a week) is way higher than the national average (41 h a week) (ILO 2021a). A persistent culture of overtime can be indicative of a lack of strategic planning and proactive management practices and at the same time that suggests poor work-life balance policies and a disregard for employee well-being. Addressing these issues is crucial to ensure the well-being of employees, optimize productivity and establish a healthy and sustainable work environment. The Cabo de Gata (Spain) package performance regarding the seasonality of jobs (35–45% of the employers with temporary contracts) can be related with the fact that in Spain more than 1 in 4 job positions is covered by a temporary employer (OECD 2021). On the other hand, it can also be related with a broader concern of seasonality, which refers to the fluctuation in demand and activity levels within the tourism industry based on seasonal patterns. Addressing the seasonality issue and spreading tourism demand throughout the year is key to achieve a balanced and diversified economy, ensure better employment conditions, improve customer and community satisfaction and promote a resilient and competitive tourism industry. Finally, Albania and Greece are more predisposed to have an inferior social performance related with forced and illegal labour and also wages since these countries have, in the first place, a higher rate of estimated proportions of people living in modern slavery (6.87 and 7.91, respectively) (Walk Free 2021), and lastly, tourism average wages per month in Albania and Greece (273 and 783 USD) are lower or equal than the stipulated national minimum wage (288 and 773 USD) (ILO 2021b). Forced/Illegal labour and fair remuneration are two closely linked critical concerns within the tourism industry that are due to a large presence of vulnerable workforce (including low-skilled, migrant, seasonal and disadvantaged workers), the seasonal nature of tourism, the significant presence of informal economy, the complexity of the supply chains, the absence of collective bargaining mechanisms and the lack of awarenes and enforcement among workers, employers, and consumers about labour rights and ethical practices. To ensure that the tourism industry provides decent work, it requires concerted efforts from governments, industry stakeholders and civil society to establish and enforce robust labour laws, promote transparency in supply chains, enhance awareness among workers and employers and foster a culture of responsible business practices.

Most of the tourism packages under study are, at minimum, consistent with Health&Safety standards basic requirements. The Porto Conte (Italy) package improved the performance regarding Health&Safety in R2 as they provided sufficient evidence indicating compliance with standards and legislation and also that Workers have access to all the required personal protective equipment. It is essential to go beyond the minimum to create a safe and secure working environment in tourism due to the unique risks and challenges it presents. Proactive approaches to mitigate these risks can include risk assessment and management practices, training and education, accessibility to personal protective equipment, work-life balance promotion, emergency preparedness and establishing reporting mechanisms.

In relation to the topic Training, the major part of the packages disclouse a positive perfomance as the hours of training provided exceed the sectors minimum training hours established by each country-sector agreements or, in its absence, are higher than 20 h per year, that is the amount of training per Worker mandatory in Spain that has been taken as a baseline. Karpathos (Greece) package underperformance for this topic in both testing rounds can be related with the generalised low predisposition of Greek businesses to offer training (21.7% of all businesses) (European Commission 2021). The Divjake-Karavasta package improved the performance in this regard in R2 by increasing the number of hours of training provided. Training plays a crucial role in ensuring the professional development and competence of workers, but investing in training not only benefits individual workers but also contributes to the overall competitiveness and sustainability of the tourism industry. Effective training programs for tourism employees can help workers acquire new skills and knowledge to be able to provide high-quality services and meet the evolving needs and expectations of tourists, provide opportunities for personal growth and access better employment opportunities, stay updated with the latest industry trends, technologies and best practices fostering innovation and enabling businesses to adapt to changing market dynamics and employee retention rates as workers feel valued and invested in.

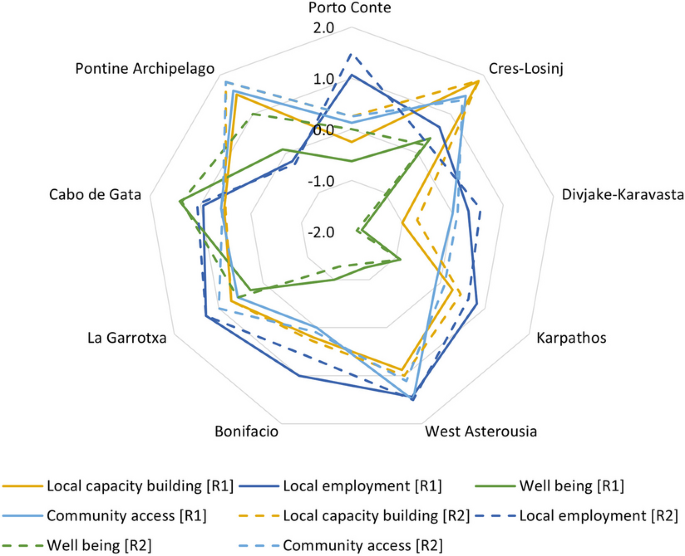

5.2 Local Community

The overall performance of the packages toward Local Community is in line with the requirements and actively promoted in most cases. An intermediate positive performance has been achieved for all packages, apart from Divjake-Karavasta (Albania), Karpathos (Greece) and Bonifacio (France) that performed in compliance with basic conditions. Even though 5 out of 9 tourism packages improved the general performance towards this stakeholder group, the results in Fig. 7 show a notable progress between the two assessment rounds for the Porto Conte (Italy) and the Pontine Archipelago (Italy) tourism packages. The social topic for which the aggregated results show a better performance is Local employment as opposed to the topic Well-being. The results for the topic Local capacity building were improved for 8 out of 9 packages. For the Community access topic, 7 tourism packages enhanced the social performance.

In relation with the various topics (Fig. 7), for Local capacity building, all packages performed at least in accordance with the established baseline for compliance. The performance of the Divjake-Karavasta (Albania) package is a consequence of the lack of partnerships and/or projects with the community. To improve the performance, it is required to implement some activities together with the community and establish a regular dialogue with them.

An exemplary conduct has been achieved by the majority of the packages for the topic Local employment. This fact is confirmed by the packages service providers employing over 95% of the workforce from the local talent pool and is strengthened by the commitment of the businesses with the skills development of the community in connection to the future needs for staffing. Also, the studied packages on average purchase more than 75% of the supplies locally. Using local suppliers in the tourism industry is of paramount importance for promoting local employment and fostering economic development within the host communities by creating employment opportunities, stimulating economic circulation within the community for a more extended period, empowering the community by providing them with a sense of ownership and pride while supporting the preservation of local traditions, crafts, cuisine and cultural practices, reducing the carbon footprint associated with transport and logistics and fostering social integration between tourists and the local community.

The social behaviour of ecotourism package service providers concerning the well-being of the local community stakeholder group is notably inadequate. A critical aspect of compliance in this context is the establishment of a robust system for monitoring residents’ perceptions of tourist activities. This generalized low performance regarding this social aspect may be attributed to its relatively low ranking on the list of concerns for tourism service providers, potentially indicating a gap in understanding or prioritizing the wellbeing of the local community in their operations. La Garrotxa (Spain), Cabo de Gata (Spain) and Pontine Archipelago (Italy) obtained a positive score since in addition to have a monitoring system in place, they also plan to take actions for improvement based on the information gathered through the monitoring system.

The results for the Community access topic that addresses the extent to which a company or facility integrates in its offer products and services for the Local Community are in general consistent with the essential requisites and positive for the majority of the packages. This scoring shows that the tourism service providers involved in the development of the packages plan and implement projects to ensure the access of the Local Community to tourist sites and other activities, plus the local language is used by the tourism businesses. Prioritizing the inclusion of the local community in activities and sites is crucial in tourism areas to ensure a harmonious coexistence between residents and tourists. This may be done by including activities that are important to the community, making sure they are affordable and accessible and preserving their cultural heritage (e.g. the local language).

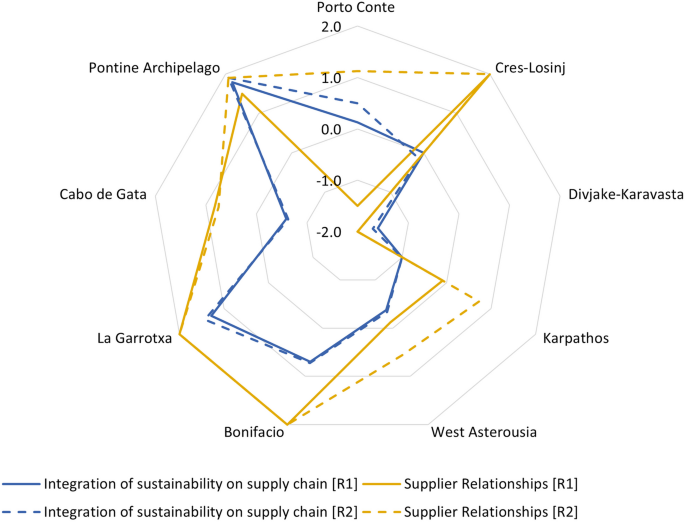

5.3 Value Chain

The overall Value Chain performance of the packages has been improved in 6 out of 9 tourism packages between the 2 testing rounds. The Porto Conte (Italy) package registered a relevant social progress in R2. An averaged higher performance has been noted for the topic Supplier relationship compared with the results obtained for the topic Integration of sustainability on supply chain.

The performance on the Integration of sustainability on supply chain topic (Fig. 8) does not meet the minimum conditions for the cases of Divjake-Karavasta (Albania), Karpathos (Greece) and Cabo de Gata (Spain) since no criterion for suppliers’ selection based on environmental and social aspects is in place. Besides developing a criterion for supplier selection based on sustainability facts, the performance can be further improved by prioritizing suppliers with sustainability reports and/or certifications. Albania and Greece have a small proportion of participants in schemes as for example the UN Global Compact (United Nations 2021) in proportion for each billion USD of GDP compared to the other countries, but out of the 6 studied countries Spain is the one with the higher number of adhesions to this specific framework.

The Supplier relationship topic results have ended up being more than just compliant with basic requirements with most of the packages showing a positive performance for this specific issue. Porto Conte (Italy) tourism package declared in R1 to have plans under development to comply fully with the obligations with regard to payments to suppliers. However, in R2, this package improved the performance and informed that most (> 85%) of the payments to suppliers were made not only within the period established by law, but also with the agreements made with the suppliers. The Divjake-Karavasta package results in both testing rounds can be linked to the fact that most payments were not aligned with the requirements for compliance. Payment to suppliers is crucial for maintaining financial stability, building trust and collaboration, supporting the social well-being of the value chain and enhancing the reputation and relationships with suppliers. This can contribute to a more ethical, sustainable and prosperous value chain, benefiting both suppliers and the broader community.

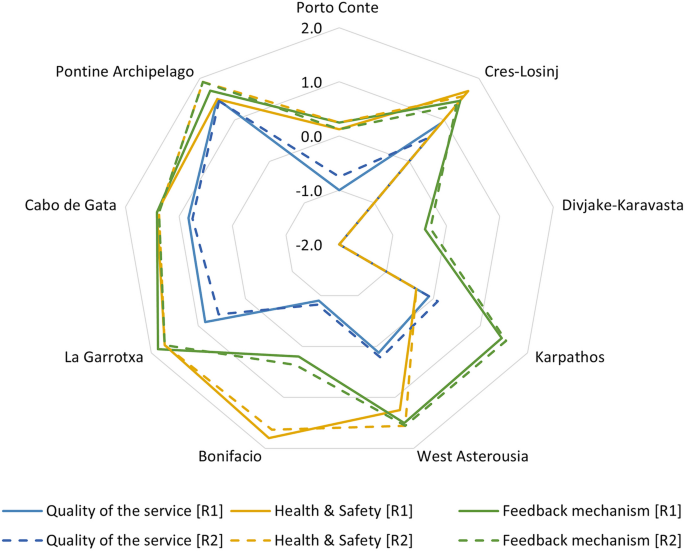

5.4 Tourists

Regarding the effects of the packages on the stakeholder group Tourists, results show a scoring going from compliant to ideal in most cases. An overall averaged relevant improvement was not perceived for this stakeholder group between the 2 rounds of the assessment and no major changes happened in any case study. Among the three topics assessed in this regard, the higher average performance of the packages corresponds to the Feedback mechanism, the lowest to the topic Quality of the service, and the topic Health&Safety falls in between the results of the 2 other topics.

For the topic Quality of the service (Fig. 9), the performance for 3 of the packages is worse than the fixed criterion. Those packages acknowledge not meeting the minimum adaptations regarding accessibility to people with disabilities. Pontine Archipelago (Italy) package claimed to provide products and services that can be mostly accessed by people with disabilities and, when this is not the case, there is the possibility to offer accessible alternatives. Coinciding with 2 out of 3 packages with a lower score, Albania and France are the countries with a smaller number of sites covered by the ISO 9001:2015 (ISO 2021) certificates per billion USD of GDP. ISO 9001:2015 specifies requirements for a quality management system when an organization needs to demonstrate its ability to consistently provide products and services that meet customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements. Italy is the country, out of the 6 under study, with a higher number of companies and facilities covered by this ISO certification. Offering services to people with disabilities is important for promoting inclusion and equal participation at the same time that expands the customer base and complies with legal and ethical obligations.

The conduct in relation with the topic Health&Safety of customers generally is in accordance or, in most cases, superior than the stipulated since most packages affirm to have a risk management plan in place that is periodically reviewed and that the Health&Safety metrics show a continuous improvement.

Most of the packages service providers have a feedback mechanism in place and, as a consequence, the results show a common proactive behaviour towards the topic Feedback mechanism. The majority of the packages also plan and implement actions based on the results obtained from this monitoring system to improve the performance towards customers.

5.5 Other perspectives on the findings

While the PSIA methodology used in the present research proposes to break down results by stakeholder group and social topic, to analyze results by category of service provider can introduce complementary information, indicating which activity drives a higher preassure on people general wellbeing (Table 5). Considering the average results of the 9 tourism packages, the social performance of Mobility is the worse among the 4 service providers categories. The most outstanding perfomance corresponds to the Accommodation category. Out of the 4 categories, social improvements have been registered for Accommodation, Food&Drinks, and Activities categories. The greater progress between the 2 testing rounds is achieved by Accommodation providers.

In general terms, Accommodation providers of the packages under assessment seem to be proactive in relation with their social performance and tend to implement actions that bring positive effects on people. The main negative issues can be related with the companies or facilities limited capacity to hire from the local pool talent or to set the conditions to make this happen in a near future. Being able to do so is important since it signals that you are investing in the areas’ growth, the wellbeing of citizens and the health of local economy, enabling communities to help themselves. Additionally, Accommodations seem to be lacking of systems to monitor the perception of the residents with regard to the tourism development in the area. Many localities think that the growth of tourism has a variety of detrimental effects on their culture and way of life, but at the same time the benefits of tourism to a town can also be significant. It is impossible to separate the social, cultural and economic effects of tourism on a host community, and different community groups and people may have different ideas about what is good for the neighborhood and what is bad. Communities might not get a chance to express their desire for change or decide against it before it occurs, so there must be agreed-upon objectives for community-based tourism if it is to be sustained.

The Food&Drinks group does not appear to be as committed to improving their capacity to offer advantages to people as the Accommodations group is. The primary concerns, in this regard, also include the development of monitoring frameworks to gather information and take action regarding residents’ perception on tourism. A lack of responsibility from Food&Drinks service providers in relation with the selection of their suppliers considering environmental and social sustainability aspects has been found for various case studies. Supply chains can be responsible for a big part of a company or facility impacts, therefore organizations can make a big difference by properly managing their network.

Relating with Activities service providers, the situation is similar as for Food&Drinks regarding social impacts, and as well their main point of conflict is associated with the presence of selection criterion for suppliers based on sustainability considerations. On the other hand, for the Mobility providers in addition to issues related with the residents’ perception of tourism impacts and the sustainability criterion for supplier selection, organizations could benefit also from a higher engagement with the Local Community through the development of partnerships. Community involvement is the power to bring positive, measurable change to both the communities in which you operate and to your business and can include financial actions but also other kinds of collaborations. The accessibility to people with disabilities could also be improved by Mobility providers and take into consideration other needs besides wheelchair accessibility. Finally, transport companies should more often place mechanisms for customers to provide feedback since it is important to improve the customer experience and overall customer satisfaction levels. It is worth noting that a number of data gaps were evident solely for the Mobility providers, and a lack of data is frequently correlated with an opaque supply chain.

6 Conclusions

This paper has successfully bridged the gap between the available studies addressing tourism social issues and the lack of a scientific framework that enables evaluation and informed decision-making. The customized PSIA methodology for tourism products is an important first step in determining the applicability of the PSIA method and S-LCA approach in the tourism industry.

The results confirm its appropiateness in quantifying and qualifying the social impacts of tourism packages and that at the same time typical input data issues have been overcomed by obtaining data directly from service suppliers. It has also been proved to be effective for enhancing the social performance of tourism service providers since it was achieved for 6 out of 9 tourism packages throughout an iterative process after providing improvement plans to all the service providers and LECs based on the results of the first assessment. The guidelines for benchmarking enable the production of valuable recommendation for decision-making, highlighting performance problems and improvement potentials. Furthermore, the assesment allows to establish crucial connections between social aspects of the tourism packages with endemic social issues faced by the regions, thereby fostering the generation of important insights and knowledge.

In our assessment, the highest benefits from the tourism packages are seen by Tourists, notably in feedback mechanism structures. Conversely, the Value Chain stakeholders experience the lowest benefits, primarily due to the absence of sustainable practices in supplier selection. For Workers, the most significant area for improvement lies in the Health&Safety, while for the Local Community, it is in addressing the residents’ perception of tourism’s impact. In the action plan to enhance overall performance, it is essential for the Value Chain stakeholders to focus on integrating sustainability criteria in supplier selection. Furthermore, considering the suboptimal performance of the majority of ecotourism package service providers in monitoring the Local Community’s perceptions of tourism, it becomes imperative to continuously assess the wellbeing of the local community in the context of tourism activities. For Tourists, the action plan must prioritize accessibility to people with disabilities to the tourism services and products. Regarding Workers, it is important to implement a robust Health&Safety policy that not only complies with regulations but also exceeds them. These strategic actions and all the other actions discussed in this paper are crucial for promoting a sustainable approach in tourim development.

The key component of any S-LCA is the identification of pertinent social topics and the use of appropriate indicators to evaluate them. The set of indicators and social topics proposed in this study can serve in data collection and as starting point to reach the creation of generalized approaches to assess the social impacts of tourism products. Future studies can expand on the identification of topics and the creation of indicators for the social assessment of sectors that form integral parts of the upstream and downstream components of the system thus enabling a comprehensive assessment that transcend the gate-to-gate approach of this study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the information they contain, which could compromise the privacy of research participants. To mitigate the risk of disclosing confidential information, results have been presented in an aggregated form.

Abbreviations

- LCA:

-

Life cycle assessment

- LEC:

-

Local ecotourism cluster

- PA:

-

Protected area

- PSIA:

-

Product social impact assessment

- S-LCA:

-

Social life cycle assessment

- WTO:

-

World Tourism Organization

References

Arcese G, Lucchetti MC, Merli R (2013) Social life cycle assessment as a management tool: methodology for application in tourism. Sustainability (switzerland) 5:3275–3287. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5083275

Arzoumanidis I, Walker AM, Petti L, Raggi A (2021) Life cycle-based sustainability and circularity indicators for the tourism industry: a literature review. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13:. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111853

Cadarso MÁ, Gómez N, López LA, Tobarra MÁ (2016) Calculating tourism’s carbon footprint: measuring the impact of investments. J Clean Prod 111:529–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.019

Cheer JM, Milano C, Novelli M (2019) Tourism and community resilience in the Anthropocene: accentuating temporal overtourism. J Sustain Tour 27:554–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1578363

Ekener E, Hansson J, Gustavsson M (2016) Addressing positive impacts in social LCA—discussing current and new approaches exemplified by the case of vehicle fuels. Int J Life Cycle Assess 23:556–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1058-0

European Commission (2016) The European Tourism Indicator System: ETIS toolkit for sustainable destination management. Publications Office

European Commission (2021) Database - Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database. Accessed 17 Mar 2021

Fürtner D, Ranacher L, Perdomo Echenique EA et al (2021) Locating hotspots for the social life cycle assessment of bio-based products from short rotation coppice. Bioenergy Res 14:510–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-021-10261-9

Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) (2016) GSTC Industry criteria. Performance indicators for hotels and accommodations and corresponding SDGs

Gnanapala A, Sandaruwani JA (2016) Socio-economic impacts of tourism development and their implications on local communities. Int J Econ Bus Adm 2:59–67

Goedkoop MJ, de Beer IM, Harmens R et al (2020) Product social impact assessment handbook - 2020. Amersfoort

Gössling S (2013) Tourism and water: interrelationships and management

Higgins-Desbiolles F, Carnicelli S, Krolikowski C et al (2019) Degrowing tourism: rethinking tourism. J Sustain Tour 27:1926–1944. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1601732

ILO (2021a) Working time. https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/working-time/. Accessed 1 Apr 2021

ILO (2021b) Wages. https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/wages/. Accessed 1 Apr 2021

ISO (2021) The ISO Survey. https://www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html. Accessed 24 Mar 2021

Köberl J, Prettenthaler F, Bird DN (2015) Modelling climate change impacts on tourism demand: a comparative study from Sardinia (Italy) and Cap Bon (Tunisia). Sci Total Environ 543:1039–1053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.03.099

Kronenberg K, Fuchs M (2021) The socio-economic impact of regional tourism: an occupation-based modelling perspective from Sweden. J Sustain Tour 30:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1924757

Lenzen M, Sun YY, Faturay F et al (2018) The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat Clim Chang 8:522–528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

Lobsiger-Kägi E, López L, Kuehn T et al (2018) Social life cycle assessment: specific approach and case study for Switzerland. Sustainability (Switzerland) 10:. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124382

Mancini MS, Evans M, Iha K et al (2018) Assessing the ecological footprint of ecotourism packages: a methodological proposition. Resources 7:. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7020038

McLeod M, Dodds R, Butler R (2021) Introduction to special issue on island tourism resilience. Tour Geogr 23:361–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.1898672

Muler Gonzalez V, Coromina L, Galí N (2018) Overtourism: residents’ perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity - case study of a Spanish heritage town. Tourism Review 73:277–296. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2017-0138

OECD (2021) Temporary employment. https://data.oecd.org/emp/temporary-employment.htm. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Organización Mundial del Turismo (2018) La contribución del turismo a los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible en Iberoamérica. OMT, Madrid

Organización Mundial del Turismo (2020) El futuro del trabajo en el turismo y el desarrollo de competencias. OMT, Madrid

Ramirez PKS, Petti L, Haberland NT, Ugaya CML (2014) Subcategory assessment method for social life cycle assessment. Part 1: methodological framework. Int J Life Cycle Assess 19:1515–1523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-014-0761-y

Ramkissoon H (2020) Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: a new conceptual model. J Sustain Tour 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1858091

Sánchez del Río-Vázquez ME, Rad C, Revilla-Camacho M (2019) Relevance of social, economic, and environmental impacts on residents’ satisfaction with the public administration of tourism. Sustainability 11:6380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226380

Scott D, Gössling S (2018) Tourism and climate change mitigation. Embracing the Paris Agreement. European Travel Commission

UNEP (2020) Guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products and organizations 2020. Benoît Norris, C., Traverso, M., Neugebauer, S., Ekener, E., Schaubroeck, T., Russo Garrido, S., Berger, M., Valdivia, S., Lehmann, A., Finkbeiner, M., Arcese, G. (eds.). United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

United Nations (2021) United Nations Global Compact. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/interactive. Accessed 19 Apr 2021

Walk Free (2021) Global Slavery Index. https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/2018/data/maps/#prevalence. Accessed 18 Mar 2021

World Tourism Organization (WTO) (2004) Indicators of sustainable development for tourism destinations. A guidebook

World Travel & Tourism Council (2021) Travel & tourism economic impact 2021. Global Economic Impact & Trends 2021

Zagonari F (2019) Multi-criteria, cost-benefit, and life-cycle analyses for decision-making to support responsible, sustainable, and alternative tourism

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. The EU’s Interreg MED funding Programme financed the DESTIMED PLUS– “Ecotourism in Mediterranean Destinations: From Monitoring and Planning to Promotion and Policy Support” project (Interreg-MED programme code 5270). Additionally, Joan Colón has received funding from the 2018 call for Ramón y Cajal grants from the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (ref. RYC-2018–026231-I) co-financed by the State Research Agency and the European Social Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Sara Russo Garrido.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miralles, C.C., Roura, M.B., Salas, S.P. et al. Assessing the socio-economic impacts of tourism packages: a methodological proposition. Int J Life Cycle Assess 29, 1096–1115 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-024-02284-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-024-02284-z