Abstract

To what extent does the co-existence of the empowering Internet and resilient authoritarianism rely on the state-controlled information environment? Drawing on online ethnography and a dataset of Amazon reviews, this article addresses the question by examining the debate over the memoir of a Chinese-American entrepreneur. It finds that such digital experiences, though in a free information environment, have resulted in frustration, anger, and ultimately disenchantment with the West among overseas Chinese. The findings contribute to the growing literature on digital orientalism and digital authoritarian resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To explain enduring authoritarianism in the digital era, scholars have explored how authoritarian states have adapted to the challenges through controlling and manipulating online information [12, 13]. To what extent does the paradoxical co-existence of the empowering Internet and resilient authoritarianism rely on the state-controlled information environment? Taking a dramaturgical perspective and drawing on online ethnography and a dataset of Amazon reviews, this article traces how overseas Chinese and those critical toward the Chinese regime, mostly foreigners, debated the memoir of a Chinese-American entrepreneur Ping Fu. In doing so, it not only reveals the contested impressions of Fu and China, but also shows how such everyday experiences have resulted in frustration, anger, and ultimately disappointment among many overseas Chinese. I argue that such a mechanism of “digital disenchantment”—a sense of awakening from the prior imagination of the West, especially the U.S.—may contribute to authoritarian resilience. The findings show that even in a free information environment, everyday online interactions may work to the advantage of an authoritarian state by eroding the trust in the liberal democratic system and by validating authoritarian propaganda. Moreover, by focusing on a mundane case rather than a salient nationalist incident or major crisis [17, 76, 80, 88], this article helps reveal the more nuanced, everyday dynamics of global digital politics, nationalism, and regime support.

Digital Politics, Nationalism, and Authoritarian Resilience

By enabling freer information, the Internet has helped challenge authoritarian rule [15, 39, 67, 82]. Yet, strong authoritarian regimes like China have survived the digital challenges. To explain the paradoxical coexistence of the empowering Internet and enduring authoritarianism, scholars have highlighted how authoritarian states have adapted through enhancing censorship and embracing innovative propaganda strategies as well as using the Internet to surveil the public and demobilize collective action [12, 13, 46, 47, 49, 63, 79].

However, attributing digital authoritarian resilience solely to state control and manipulation is problematic. First, the argument runs the risk of portraying non-Western societies like China as inherently abnormal. Such a perspective, conceptualized as “digital orientalism” by Maximilian Mayer and highlighted in this special issue [56, 57], assumes that the West, particularly the U.S., represents an ideal society whose values and practices will be inevitably adopted by the rest of the world [54]. Societies like China have fundamentally flawed and illegitimate systems that are not appealing internationally or domestically, thus relying primarily on repression for survival. Second, the argument implies a dyadic “state control versus societal resistance” framework and sees the Internet as inherently subversive. Yet, studies show that authoritarian cyberspace is often fragmented, and the majority of online activities are not politically motivated [11, 52]. Even when citizens are politically motivated, they may side with the state [32, 45, 58, 61], thus diluting, neutralizing, and suppressing the liberalizing and democratizing effects of the Internet [33].

Authoritarian regimes can remain popular in the digital age for multiple reasons. Besides factors such as performance legitimacy [84], citizens’ pro-regime tendency is often associated with nationalist causes [33, 61, 78]. For instance, netizens believing that online expression can be manipulated by hostile forces to sabotage China would often defend the Party-state voluntarily [33]. Similarly, perceived institutional, financial, and ideational ties with the West has contributed to the popular defamation of “public intellectuals,” which in turn works to the state’s advantage [32]. Such findings echo studies that find nationalism as an important element of populist authoritarianism [26, 35, 70] and populist politics in general [37, 60, 75].

Though nationalism helps explain digital authoritarian resilience, it is still unclear to what extent nationalist support (and popular support in general) for authoritarianism is conditioned by the state’s effort to shore up legitimacy through state-sponsored nationalist campaigns and patriotic education as well as its ability to control and manipulate information in the digital age [6, 26, 68, 74, 87]. After all, popular nationalism in today’s China is also shaped by international, market, societal, and media forces [10, 36, 42, 43, 51, 64, 71, 78, 89], thus it can escape state control and challenge the state’s claim to nationalist legitimacy [23, 65, 66, 85].

How do digital experiences beyond state control affect nationalism and regime support? Since nations are collectively imagined communities [2] and citizens’ support for the government hinges on how they perceive other countries or threats [3, 26, 41], it is natural to expect nationalism and regime support to be affected when citizens are exposed to freer information and foreign influences. In this regard, current studies on overseas Chinese nationalism [31, 53, 55, 59], though inspiring, have yet to pay sufficient attention to the effects of information access and direct communicative interaction with communities and individuals outside China.

Scholars have explored the effects of cross-national experiences. However, the findings are inconclusive. Some find overseas returnees more “internationalist” and less nationalistic [30] while others show that overseas Chinese students are patriotic and supportive of the Chinese regime [27, 73]. Still others discover that while education in social sciences and consumption of foreign media increase support for democracy, living overseas tends to decrease one’s support for China to pursue democracy [29]. The conflicting arguments suggest that further research is necessary to identify the impact of cross-national experiences on attitudes toward authoritarian rule.

Through dramaturgical analysis of the controversy over Ping Fu’s memoir which primarily took place on overseas digital platforms and focused on a non-nationalistic topic, this article aims to reveal how everyday digital experiences of overseas Chinese in an uncontrolled information environment may work to the advantage of authoritarian rule in China.

Methodological Approach and Data

In his seminal work The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, sociologist Erving Goffman draws on the language of the theater to develop a dramaturgical model to analyze social interaction [21]. According to Goffman, an individual, when in the presence of others, acts like a performer on a social stage who constantly tries to influence the “definition of situation” and to “manage impressions” of himself by manipulating the setting of the performance, one’s appearances, and the manner. Here definition of the situation refers to the setup of the interaction so that the performer and the audience know what to expect of each other; and such a performance can be understood as presentation of self or self-presentation, as used by later researchers [4], by the performer to foster an idealized image of himself and encourage others to accept it. Other than the performer, others present at the performance can be seen as the audience, observers, or co-participants. For the audience, the performer’s expressive behavior includes both the expressions he gives (often in an intentional and controlled way to project his idealized impressions) and the expressions he gives off (impressions not intentionally projected but received by the audience). Goffman further highlights the interactivity in the process, noting that “[t]he others, however passive their role may seem to be, will themselves effectively project a definition of the situation by virtue of their response to the individual and by virtue of any lines of action they initiate to him” ([21]: 3). Meanwhile, this interactive nature of the process means that the audience can be engaging in the “presentation of self” from the perspective of the performer or other viewers.

Since Goffman, scholars across disciplines have employed the dramaturgical model to examine how social actors interact in various social, cultural, and political realms [5], including that of cyberspace [8, 14, 28]. Although Goffman never anticipated the digital age, online experiences are often ultimately about various actors preforming to define the situation and to manage impressions. And the performer-audience framework is especially suitable to study digital life given its interactive nature. However, the fluid, fuzzy, and multi-faceted nature of the virtual interaction makes it particularly difficult for any actor to set the stage, define the situation, and ultimately manage the impressions. An actor often engages multiple groups of audiences both synchronously and asynchronously online with no control over where the interaction takes place, which the audience is, or how different audience groups may react to the performance. After all, the performance may take place on multiple digital platforms (or stages) with different technological affordances that attract users with different behavioral norms. Moreover, the interaction being both synchronous and asynchronous means that an actor’s performances in different settings can be brought together, re-composed, re-performed, and re-interpreted by the audience as they wish. Since multiple audience groups are present, a successful self-presentation in front of one audience group may give off undesirable impressions for another group, and any perceived effort to customize impression management may backfire, as it not only projects conflicting self-presentations but also gives off the impression of the performer being insincere and opportunistic.

The analysis below examines the controversy over Ms. Ping Fu’s memoir from the dramaturgical perspective. On December 31, 2012, Chinese-American entrepreneur Ping Fu published her memoir Bend, Not Break: A Life in Two Worlds. A typical rags-to-riches story at first glance, the book quickly stirred up a controversy among Chinese netizens at home and abroad who fiercely questioned Fu’s veracity, especially her experiences during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) [19, 22]. Unlike incidents such as the Beijing Olympics, the Hong Kong protests, the Meng Wanzhou case, or the COVID-19 pandemic, which are imbued with nationalist sentiment [17, 76, 80, 88] driving Chinese diasporic communities “to rally around Beijing and assert their Chinese identity on a global scale” [53], the mobilization against Ms. Fu was not state-sponsored, nor was it nationalistic in nature. At the core of the controversy was Fu’s experience during the Cultural Revolution, which is neither something that would boost nationalist pride nor a foreign infliction [24]. Moreover, the controversy took place primarily overseas. Thus, probing into the case can help illuminate the mechanism that may contribute to authoritarian resilience in a free information environment.

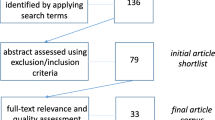

To gather data, I conducted “guerilla ethnography” by exploring online platforms where the book is discussed (such as the popular overseas Chinese forum Unknown Space, Mitbbs.com) and followed links on these sites to media coverage on the book, readers’ debates, as well as mobilization of overseas Chinese [38, 81]. To examine how supporters and criticizers of the memoir engaged one another, I also scraped all 913 reviews of the book from Amazon, creating a dataset that contains each review entry’s title, content, reviewer username, posted date, rating, word count as well as the counts of comments and upvotes the review has. A research assistant and I coded the general tone of the reviews (positive or negative) and the identity of the reviewers (Chinese, non-Chinese, unknown; here “Chinese” are primarily overseas Chinese in the U.S. and non-Chinese Americans with non-Chinese origin since we focus on Amazon). See Appendix 1 for the coding process.

The Multi-Round Performer-Audience Interaction over the Ping Fu Controversy

The controversy over Bend, Not Break can be understood as a multi-round performer-audience interaction process. From the dramaturgical perspective, Fu’s memoir, especially her described experiences in the Cultural Revolution, presented herself as a woman achieving tremendous success against all odds while presenting China as a horrible authoritarian state [20]. Such presentations of self and China were highlighted and amplified by the promotion of the memoir in mainstream Western media [72]. But many Chinese at home and abroad directly contested Fu, arguing that she was a liar. They piecemealed evidence from multiple sources that gives off impressions of Fu that are inconsistent with what her 2012 memoir gives, revealing Fu’s impression management attempts while projecting different presentations of Fu and China. These criticizers were met with Fu’s supporters who defended Fu and defined the criticism toward Fu as a Chinese state-sponsored smear campaign. This performance by Fu’s supporters was subject to further interpretation and contestation, which, I argue, ultimately resulted in “digital disenchantment” among many overseas Chinese. A closer examination of the review war on Amazon through critical discourse analysis below helps illustrate the process.

According to Norman Fairclough, critical discourse analysis has three dimensions: text, discursive practice, and social practice [16]. At the text level, I conduct a computer-aided keyword analysis supplemented by a close reading of the texts. At the discursive practice level, I explore the engaging tactics of both criticizers and supporters of Fu, with a special focus on overseas Chinese. At the social practice level, I show how such presenter-audience interactions have led to what I call digital disenchantment. Note that the primary purpose of the discourse analysis here is to reveal how involved actors were engaging one another in the discursive interaction rather than explore how the discourse is produced or made within.

Before examining how different actors engaged each other, it is useful to see whether the review war was truly identity based. Table 1 shows how the overall tone of a review interacts with the reviewer’s identity (Appendix 1 explains the coding process). The debate was clearly identity based, with 87 percent of non-Chinese supporting Fu and 94.5 percent of Chinese criticizing her. A computer-aided keyword analysis confirms the observation (see Appendix 2 for details).

Engaging Tactics and Impression Management in the Review War

Further analysis of the discursive practice dimension of the review war reveals that unlike typical nationalist mobilization where both sides start with confrontational stances, overseas Chinese in this case deployed engaging tactics that differentiate them from “angry youth” nationalists acting violently in demonstrations or the “Little Pink” using soft emotional discourse and memes [18]. Close reading of the reviews shows three major engaging tactics employed by overseas Chinese.Footnote 1 To protect the privacy of research subjects, the analysis below refers to specific review entries only by their case numbers. The data will be available upon request.

First, like some other nationalist mobilization cases that involve debates on what the “real China” is [50], Chinese reviewers put special emphasis on factual evidence when presenting their accusations against Fu. The first critical review of the memoir, by Amazon user lin, staged a factual rebuttal with seven specific points. This review was the most commented on (980 times) and upvoted (1,614 times) among all, suggesting that Chinese reviewers agreed with not only its content, but also the engaging tactic. After lin, many other Chinese reviewers also wrote long fact-checking reviews detailing the inaccuracies, drawing on multiple sources including official documents (or the lack thereof), witness testimonies, media reports, and Fu’s own earlier memoir. This is why their reviews were much longer than foreign reviews on average (mean word counts: 206.6 versus 139.2). In fact, several overseas Chinese even compiled the evidence and published a 152-page book The Bent and Broken Truth which criticizes Fu almost line by line [77]. By basing their accusations on factual evidence, they attempted to define the situation as truth and facts versus falsehood and lies. In doing so, the criticizers presented Fu as a liar rather than a China-traitor and themselves as truth speakers rather than China-defenders, avoiding a direct identity and cultural confrontation with non-Chinese reviewers.

Chinese reviewers resorted to personal or family experiences. One reviewer who saw the memoir as “written with Ms. Fu’s imagination, not her experience,” claimed that he had lived in the city where Fu migrated from for 26 years.Footnote 2 Another reviewer argued (typos corrected from the quote to avoid confusion),Footnote 3

Both of my parents have experienced the Cultural Revolution and actually they met each other during that hard period of time and got married after being together for 11 yrs. Both of my parents were among the smartest students at their school and both of them were deprived the rights to study when they were teenagers, instead, they were sent to villages in the north for another kind of "study"… My parents have told me all they have experienced, the harsh condition etc. But when I told them what Fu wrote, both of them said she was a liar without any hesitation.

Such living experiences serve as witness testimonies intended to present the reviewers as reliable, adding to the authenticity of their criticism toward Fu.

Second, another major discursive feature of Chinese reviewers was their effort to make their points relatable to non-Chinese reviewers, again to define the situation not as one of China versus the U.S. or Chinese against non-Chinese. The authors of The Bent and Broken Truth, mentioned above, claimed that either they or their family members had suffered in the Cultural Revolution and explicitly dedicated their work to “those who valiantly defended the American values in furtherance of life, liberty, and our pursuit of happiness” and their “American-born children, who will grow up in our Land of the Free, waving the Star-Spangled Banner” [77].

Chinese reviewers tried to link the controversy to events that foreigners are more familiar with. They referred to Lance Armstrong, who was sued for marketing his memoirs as “true and honest” nonfictional works while much in them were in fact mendacious [9], and James Frey, who was sued for fabricating stories in his autobiography [62]. Furthermore, believing that Fu was a member rather than a victim of the Red Guards, one Chinese reviewer asked, “What if someone labeled himself as a Holocaust survivor, wrote a memoir to iterate his sufferings, but turned out to be a Nazi instead?”Footnote 4 The analogies not only functioned to signal that Fu was just another fraud; they also resorted to compassion with the hope that foreigners could understand why Chinese felt so strongly about Fu as her lies were not simply attacks on China but on all humanity.

Third, in the discursive interaction, Chinese reviewers directly approached foreign reviewers to persuade them. On average, each foreign review received three times the number of comments than that of a Chinese reviewer (18.32 versus 5.61). Foreign reviews supporting Fu had even more comments (mean=20.86), indicating Chinese reviewers’ extra effort to persuade those disagreeing with them. Chinese reviewers also showed strong eagerness to befriend foreign reviewers. The most-commented review by a foreigner (211 times, only second to lin’s factual rebuttal mentioned above) rated Fu’s memoir positively but regarded Chinese reviewers’ points as “sobering, extremely important and thought provoking,” saying, “Each side has taught me something, and I am honored to have read all opinions.”Footnote 5 Her open-mindedness earned respect from Chinese reviewers, who befriended her and shared with her more stories (perhaps to convince her further). Moreover, critical reviews toward Fu by non-Chinese were upvoted much more (mean=36.72) than positive reviews by non-Chinese (mean=8.49), likely because Chinese reviewers supported foreigners on their side and wanted to popularize the reviews that might better speak to non-Chinese readers. Again, Chinese reviewers’ discursive practice here was to present themselves as approachable and to avoid defining the situation as a nationalist attack on Fu and her supporters.

Overall, Chinese reviewers emphasized factual evidence, attempted to be more relatable, and tried to engage the non-Chinese reviewers directly. Such engaging tactics were not just for the purpose of persuasion but also for presenting themselves as citizens in a free society and truth-seekers who wanted to have a dialogue instead of the hot-headed nationalists or state agents that Fu’s supporters claimed them to be. However, such engaging discursive tactics were overall not quite effective. Despite some amicable interactions with the non-Chinese reviewers, Chinese reviewers found their presentation of self and definition of the situation largely rejected by the other side. With very few exceptions, both sides appeared confused and irritated. Chinese reviewers could not understand why foreigners defended a liar, given the abundant factual evidence. Fu’s foreign supporters, however, did not understand why the Chinese targeted an individual, regarding their criticism dubious or part of a state-coordinated smear campaign. Though Chinese reviewers denounced the Cultural Revolution and even invoked American values, they were dubbed “mindless drones working for the Chinese government”Footnote 6 and their reviews “mass produced variants on denying that the Cultural Revolution actually took place.”Footnote 7 For Fu’s supporters, the suspicion was not totally unfounded, but based on the impressions Chinese reviewers seemingly gave off: those critical reviews came in bursts, were mostly by those who had no other review on Amazon, and were often not based on actual reading or at least purchase of the book.Footnote 8 All such indicators suggested to them that attacks on Fu were part of a coordinated campaign, especially given that the Chinese state indeed had such a record [33, 47].

Defining the situation as an individual against a repressive regime, Fu’s supporters disagreed with Chinese reviewers on whether the inaccuracies matter at all. For the supporters, Fu’s stories only confirmed the notoriety of the Cultural Revolution. Since the knowledge about what actually happened to Fu lies only with her, the critics were in no position to judge her. Some supporters did not even care if her account was reliable since it is “a memoir, not journalism.”Footnote 9 After all, Fu was writing about her experiences from a time when “she was a child in a very turbulent situation… struggling to survive.”Footnote 10

For Chinese reviewers, how foreign reviewers reacted to them had become a performance that gave off impressions of the Western public. Probably subconsciously, Chinese reviewers deemed themselves to be more authoritative sources on China, expecting their voices to be taken seriously by those who could rely on only secondary, often unreliable, accounts of China. It was frustrating for them to find that their self-presentation as truth-seekers and reliable sources were rejected. The excerpt below captures the tensions nicely (typos corrected to avoid confusion):Footnote 11

Interesting enough, many negative reviews made by the Chinese were talking about the facts. They showed the inconsistency of Fu's own words. They used different resources supporting their claims and pointed out the conflicts b/t Fu's claims & the logic. However, those westerners who gave high rating & positive reviews were talking about how inspiring Fu's story is. They talked about how they have been touched emotionally. They only read Fu's own words but not to be bothered to do some fact-checking. They even did not read through all those negative reviews or think carefully on those questions that have been raised before accusing others as "coordinated campaign" or "paid by the Chinese government".

Digital Disenchantment and Authoritarian Resilience

The controversy over Ping Fu represents a form of overseas Chinese activism that differs from typical nationalist mobilization [53] and cross-cultural confrontations that arise from conflicting identities [27] or extensive links with the home country [55]. As my analysis shows, overseas Chinese attempted to have a dialogue by downplaying their identity, embracing foreign values, and reaching out to foreigners. By emphasizing factual evidence and accusing Fu as a liar, they presented themselves as truth-seekers more than China-defenders. Yet, for the overseas Chinese, their digital experiences had staged a live performance of the West, more specifically America, which presented the Western public, media, and governments as not only perceiving China in a strongly biased way but also showing little interest in deliberation. Such experiences had led to “digital disenchantment” as many of them were in a sense awakened from the myth of the West (the U.S.) being perfect—the beacon of human society [54]. Since they did not try to isolate themselves, but instead actively engaged non-Chinese reviewers, it was frustrating that they were perceived as defenders or even agents of the Chinese regime. This not only made overseas Chinese feel alienated, as such experiences reminded them of being an excluded group in the host country, but also led them to lose trust in Western governments, media, and institutions as they extended their experiences beyond the Amazon review war. In short, the controversy over Ping Fu was like a wakeup call, reminding them that the West (the U.S.) had failed to live up to the idealized expectations of a liberal democratic society.

Indeed, the frustration, anger, and disappointment among overseas Chinese were extended to the American public, media, government, as well as liberal democratic values. A Chinese American, cited in quite a few Amazon reviews, expressed the sentiment well in his blogs,Footnote 12

These Americans are ‘naive to the point of cute’. […] They seem to think that as long as her message is against something evil, it is ok to lie. […] It makes it harder to promote democracy in China, and reinforces the image of American ignorance and arrogance.

Many of these Americans have accused critics of Ms. Fu, including myself, as shills of the Chinese government. This angers me more than the lying by Ms Fu. It is a combination of McCarthyism and racism that any card-carrying liberal should be ashamed of.

The same blogger targeted the American media and mainstream culture,Footnote 13

The American (and Western) media, instead of examining the inconsistencies in her book and accepting that they made a big mistake, started to attack her critics as ‘shills’ of the Chinese government. The Chinese American community were insulted first by Ping Fu's lies, then abused by the media. It is a spectacular display of the ignorance and arrogance of the mainstream American culture.

Another Chinese reviewer directly questioned democracy using a falsified quote from ancient Greek Historian, Isocrates,Footnote 14

"Democracy destroys itself because it abuses its right to freedom and equality. Because it teaches it[s] citizens to consider audacity as a right, lawlessness as a freedom, abrasive speech as equality, and anarchy as progress." - Isocrates

Note that by “disenchantment,” I do not mean enlightenment. Chinese reviewers’ views may very well be flawed and biased. Many of them failed to recognize that Western media outlets such as The Guardian and Forbes actually covered the controversy and were critical toward Fu. And their expectation of the U.S. (and the West) to be perfect might be an illusion from the very beginning. They were disenchanted in that their prior beliefs were shaken, perceiving the U.S. (and the West) as failing to live up to their idealized expectations. For some, the very fact Fu as a dishonest person succeeded in the U.S. and did not receive any meaningful punishment despite their outcry was disappointing and disillusioning.

While the digital disenchantment experiences may not automatically translate into support for authoritarian rule, they could indirectly benefit the Chinese Party-state. Studies show that more negative perceptions of democracies may boost one’s support for an authoritarian regime [40, 41]: if the U.S. and the liberal-democratic system are not perfect, one would probably have lower expectations toward China and its government. Furthermore, such experiences help validate and justify the Chinese state’s propaganda of hostile foreign forces constantly trying to demonize China. In one reviewer’s words,

The government of China, rightly or wrong, will inevitably think that this is another example of western 'hegemony' against it … A book like this, based on essentially all made up accounts, and having being heavily promoted here in US, does not help advance the case for the gradually loosening of the government's heavy hand in regulating the flow of information in China.Footnote 15

While it is unclear if the Chinese reviewer quoted here was disenchanted or not (he was speaking to non-Chinese reviewers, therefore, might be conducting impression management), comments from other overseas Chinese websites provide more direct evidence of how the controversy might have discredited democracy and benefited the Chinese authoritarian regime. On major overseas Chinese websites, BackChina and Wenxuecity, users commented,Footnote 16

Americans are not stupid, but only serving their own political interests. So far as someone is anti-communism and anti-China, Americans would treat him as a model for democracy and freedom…

It seems that democracy needs liars and democracy welcomes liars. To lie for democracy is not a big deal at all.

Ping Fu actually has made a huge contribution. For decades, hostile forces have used horrible experiences of some being repressed during the Cultural Revolution to viciously attack the Chinese government and system. The fact that Ping Fu lies in her memoir is sufficient for us to deny the multitude of unfounded bashing of the Cultural Revolution, allowing us to confidently proclaim that the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was good. Ping Fu should be awarded.

Even Boxun, an overseas Chinese dissident website, got backfired for posting an article defending Fu, with multiple users expressing disappointment in the platform. One user commented, “You lost all your credibility with shit like this.”Footnote 17 Another said, “[G]ood bye, [B]oxun, it's a shame you could not tell a lie and truth. [I] won't surf this stupid website anymore!”Footnote 18 The strong words used here indicate the extreme disappointment, showing how the controversy over Fu may have eroded the supporting base of overseas dissident activism.

Conclusion

Unlike typical cases of nationalist mobilization that have attracted much scholarly attention, the controversy over Ping Fu’s memoir is a mundane one that resembled more closely the daily interaction between Chinese and foreigners. While the overseas Chinese were eager to engage non-Chinese and emphasized facts rather than cultural or identity differences, they faced entrenched distrust and were constantly reminded about their Chinese identity. Such experiences, I argue, cause “digital disenchantment,” which explains why overseas Chinese may feel alienated by the host country and attached to China and even the Chinese government.

“Digital disenchantment” here boils down to the disillusion with the U.S. (the West). For that to happen, my analysis suggests that several factors may be crucial, including an audience group with high prior expectations of the West being ideal, an event that fundamentally contradicts such expectations to disappoint the audience, and the digital experiences that do not ease but instead aggravate and amplify the disappointment. In this process, the information environment matters. Presumably, a free information environment may foster discussion and deliberation, thus preventing “digital disenchantment” or soothing its impact. In this sense, the controversy over Ping Fu is a least-likely case. Why did it nonetheless happen? On the one hand, this might be due to the high (maybe unrealistic) expectations of the U.S. to be the “beacon” of the world among overseas Chinese [54]. The same reason can explain why dissident artist Ai Weiwei criticizes Germany for “becoming intolerant of refugees.”Footnote 19 On the other hand, the debate over Fu proved to be more about confrontation and conflicts than deliberation and discussion, suggesting that the free information environment alone may not avoid “digital disenchantment.”

If citizens exposed to free information can be “disenchanted,” one may reasonably expect the impact to be stronger on those in a controlled information environment. Moreover, nationalism may enhance the disenchantment effect by promoting identity-based confrontation. A recent case would be the COVID-19 pandemic which has sparked nationalism across the world [26, 37, 60, 69, 75, 86]. In China, for instance, Fang Fang, author of Wuhan Diary, while applauded in the West and by Chinese liberals, is accused of tainting China’s image, thus becoming the target of nationalist besiege [83]. Moreover, many Chinese, through observing how Western media and governments presented China in the pandemic, see the West as inherently biased. One frequently cited example was the New York Times’ two consecutive tweets on March 8, 2020: At 10:30am, the renowned media outlet first criticized China’s lockdown, saying it “has come at great cost to people’s livelihoods and personal liberties.” Only 20 minutes later, it praised Italy’s lockdown as “risking its economy in an effort to contain Europe’s worst coronavirus outbreak.” Juxtaposition of these two tweets presents a vivid example of Western media’s double standard.Footnote 20 Such an observation, which echoes official discourse [86], only fuels distrust in the Western media and governments among Chinese, especially amidst the Sino-US rivalry on multiple fronts [1].

This study shows the relevance of the dramaturgical analysis approach and the value of studying cyber politics from an everyday perspective. With impression management being fundamentally transformed in the digital age, even non-political actors’ performance can be recorded, circulated, and interpreted by various audience groups, resulting in unexpected political consequences. Ms. Fu probably never expected the backlash among Chinese. Similarly in 2015, when the 16-year-old Taiwanese singer Chou Tzu-yu waved a Republic of China flag on a TV show, she clearly did not intend to trigger a massive online mobilization that reportedly affected Taiwan’s 2016 presidential election [34]. When Shuping Yang used the air quality difference between the U.S. and China as a metaphor for her feelings toward democracy and free speech at the University of Maryland commencement, she likely did not anticipate her speech to ignite a wave of Chinese cyber nationalism [44]. All these cases represent the politicization of everyday life in the digital age when individuals who are typically not in the political realm ended up in highly political controversies when their self-presentations went out of control.

This study also reveals that the expansion of the Internet poses more than a dictator’s dilemma [67] in that democracies are also challenged. For instance, democratic societies now have to balance between allowing greater government surveillance and risking endangering state and societal security [3]. In particular, since communication online is never unidirectional, citizens and governments of democracies, besides threats such as authoritarian information infiltration and disinformation [25, 48], now also need to deal with the challenge of interacting with a more diverse, heterogeneous, and amorphous global public. Such interactions often result in clashes of perceptions, predispositions, and values, all publicly displayed and aggregated online, thus not only bearing implications for democratic politics, but also giving off impressions of democracy to outside audience groups. This process, as the Ping Fu controversy and other similar cases [50, 64] have demonstrated, may put the very ideas of liberty and openness of liberal-democratic societies to the test.

Notes

The dynamics on other digital platforms could be different from what was observed on Amazon. For instance, under a report by The Guardian with 122 comments [7], there was not much confrontation. This might be because the article was critical toward Fu, thus attracting few of Fu’s supporters.

Amazon Review #481.

Amazon Review #634.

Amazon Review #856.

Amazon Review #489.

Amazon Review #321.

Amazon Review #818.

Amazon Review #853.

Amazon Review #58.

Amazon Review #77.

Amazon Review #687.

Amazon Review #181.

Amazon Review #745.

References

Akdag, Y. 2019. The likelihood of cyberwar between the United States and China: A neorealism and power transition theory perspective. Journal of Chinese Political Science 24 (3): 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-018-9565-4.

Anderson, B. 1991. Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

Atkinson, C., and G. Chiozza. 2021. Hybrid threats and the erosion of democracy from within: US surveillance and European security. Chinese Political Science Review 6 (1): 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-020-00161-2.

Baumeister, R.F., and D.G. Hutton. 1987. Self-Presentation theory: Self-construction and audience pleasing. In Theories of Group Behavior, ed. B. Mullen and G.R. Goethals, 71–87. New York: Springer.

Benford, R. D., and A. P. Hare. 2015. Dramaturgical analysis. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition, 645–649. Elsevier Inc.

Brady, A.-M. 2009. Mass persuasion as a means of legitimation and China’s popular authoritarianism. American Behavioral Scientist 53 (3): 434–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209338802.

Branigan, T, and E. Pilkington. 2013. Ping Fu’s childhood tales of China’s cultural revolution spark controversy. The Guardian, 13 Feb. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/feb/13/ping-fu-controversy-china-cultural-revolution.

Bullingham, L., and A. Vasconcelos. 2013. ‘The presentation of self in the online world’: Goffman and the study of online identities. Journal of Information Science 39 (1): 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551512470051.

Bury, L. 2013. Lance Armstrong faces lawsuit over lies in memoirs. The Guardian, August 9.

Cong, R. 2009. Nationalism and democratization in contemporary China. Journal of Contemporary China 18 (62): 831–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560903174663.

Damm, J. 2007. The internet and the fragmentation of Chinese society. Critical Asian Studies 39 (2): 273–294.

Deibert, R., J. Palfrey, R. Rohozinski, and J. Zittrain, eds. 2008. Access denied: The practice and policy of global internet filtering. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Deibert, R., J. Palfrey, R. Rohozinski, and J. Zittrain, eds. 2010. Access controlled: The shaping of power, rights, and rule in cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ellison, N., R. Heino, and J.L. Gibbs. 2006. Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11: 415–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00020.x.

Esarey, A., and Q. Xiao. 2008. Political expression in the Chinese blogosphere: Below the radar. Asian Survey 48 (5): 752–772. https://doi.org/10.1525/AS.2008.48.5.752.

Fairclough, N. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Abingdon: Routledge.

Fan, J. 2018. How China views the arrest of Meng Wanzhou. New Yorker, 17 Dec. Available at https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/how-china-views-the-arrest-of-huaweis-meng-wanzhou.

Fang, K., and M. Repnikova. 2017. Demystifying “Little Pink”: The creation and evolution of a gendered label for nationalistic activists in China. New Media & Society 20 (6): 2162–2185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817731923.

Fang, S. 2013. Ping Fu’s life legends [傅苹的“人生传奇”]. Xin Yu Si (New Threads), 28 Jan. Available at http://xys.org/xys/netters/Fang-Zhouzi/blog/fuping.txt.

Fu, P., and M. M. Fox. 2012. Bend, not break: a life in two worlds. Portfolio/Penguin.

Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City: Doubleday & Company.

Goudreau, J. 2013. “Bend, Not Break” author Ping Fu responds to backlash. Forbes, 31 Jan. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/jennagoudreau/2013/01/31/bend-not-break-author-ping-fu-responds-to-backlash/.

Gries, P.H. 2005. China’s new nationalism: Pride, politics, and diplomacy. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gries, P.H. 2005. Chinese nationalism: Challenging the state? Current History 104 (683): 251–256.

Grinberg, N., K. Joseph, L. Friedland, B. Swire-Thompson, and D. Lazer. 2019. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science 363 (6425): 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706.

Gülseven, E. 2021. Identity, nationalism and the response of Turkey to COVID-19 pandemic. Chinese Political Science Review 6 (1): 40–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-020-00166-x.

Hail, H.C. 2015. Patriotism abroad: Overseas Chinese students’ encounters with criticisms of China. Journal of Studies in International Education 19 (4): 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315314567175.

Hall, J.A., N. Pennington, and A. Lueders. 2014. Impression management and formation on Facebook: A lens model approach. New Media & Society 16 (6): 958–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813495166.

Han, D., and D. Chen. 2016. Who supports democracy? Evidence from a survey of Chinese students and scholars in the United States. Democratization 23 (4): 747–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1017566.

Han, D., and D. Zweig. 2010. Images of the world: Studying abroad and chinese attitudes towards international affairs. The China Quarterly 202: 290–306. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030574101000024X.

Han, L. 2011. “Lucky Cloud” over the world: The journalistic discourse of nationalism beyond China in the Beijing Olympics global torch relay. Critical Studies in Media Communication 28 (4): 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2011.599848.

Han, R. 2018. Withering gongzhi: Cyber criticism of Chinese public intellectuals. International Journal of Communication 12: 1966–1987.

Han, R. 2018. Contesting cyberspace in China: Online expression and authoritarian resilience. New York: Columbia University Press.

Han, R. 2019. Patriotism without state blessing: Chinese cyber nationalists in a predicament. In Handbook of Dissent and Protest in China, ed. T. Wright, 346–360. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Han, R. 2021. Cyber nationalism and regime support under Xi Jinping: The effects of the 2018 constitutional revision. Journal of Contemporary China 30 (131): 717–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2021.1884957.

He, Y. 2007. History, Chinese nationalism and the emerging Sino-Japanese conflict. Journal of Contemporary China 16 (50): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560601026710.

He, Z., and Z. Chen. 2021. The social group distinction of nationalists and globalists amid COVID-19 pandemic. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 14 (1): 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-020-00310-6.

Hine, C. 2017. Ethnography and the Internet: Taking Account of Emerging Technological Landscapes. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 10 (3): 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-017-0178-7.

Howard, P.N., and M.M. Hussain. 2013. Democracy’s fourth wave?: Digital media and the Arab Spring. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huang, H. 2015. International knowledge and domestic evaluations in a changing society: The case of China. American Political Science Review 109 (03): 613–634.

Huang, H., and Y.Y. Yeh. 2017. Information from abroad: Foreign media, selective exposure and political support in China. British Journal of Political Science 49 (2): 611–636. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000739.

Hughes, C.R. 2000. Nationalism in Chinese cyberspace. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 13 (2): 195–209.

Hyun, K.D., and J. Kim. 2015. The role of new media in sustaining the status quo: online political expression, nationalism, and system support in China. Information, Communication & Society 18 (7): 766–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2014.994543.

Ives, Mike. 2017. Chinese student, graduating in Maryland, sets off a furor by praising the U.S. The New York Times, 23 May. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/23/world/asia/chinese-student-fresh-air-yang-shuping.html.

Jiang, M. 2016. The coevolution of the internet, (un)civil society, and authoritarianism in China. In The internet, social media, and a changing China, ed. J. DeLisle, A. Goldstein, and G. Yang, 28–48. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

King, G., J. Pan, and M.E. Roberts. 2013. How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. American Political Science Review 107 (2): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000014.

King, G., J. Pan, and M.E. Roberts. 2017. How the Chinese government fabricates social media posts for strategic distraction, not engaged argument. American Political Science Review 111 (3): 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000144.

Kuklinski, J.H., P.J. Quirk, J. Jerit, D. Schwieder, and R.F. Rich. 2000. Misinformation and the currency of democratic citizenship. Journal of Politics 62 (3): 790–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00033.

Lagerkvist, J. 2008. Internet ideotainment in the PRC: National responses to cultural globalization. Journal of Contemporary China 17 (54): 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560701693120.

Latham, K. 2009. Media, the olympics and the search for the “real China.” The China Quarterly 197: 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741009000022.

Lei, G. 2005. Realpolitik nationalism: International sources of Chinese nationalism. Modern China 31 (4): 487–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700405279355.

Leibold, J. 2011. Blogging alone: China, the internet, and the democratic illusion? The Journal of Asian Studies 70 (4): 1023–1041. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911811001550.

Li, H. 2011. Chinese diaspora, the internet, and the image of China: A case study of the Beijing Olympic torch relay. In Soft Power in China, ed. J. Wang, 135–155. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lin, Y. 2021. Beaconism and the Trumpian metamorphosis of Chinese liberal intellectuals. Journal of Contemporary China 30 (127): 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2020.1766911.

Liu, H. 2005. New migrants and the revival of overseas Chinese nationalism. Journal of Contemporary China 14 (43): 291–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560500065611.

Mayer, M. 2019. China’s authoritarian internet and digital orientalism. In Redesigning Organizations - Concepts for the Connected Society, ed. D. Feldner, 177–192. Luzem: Springer.

Mayer. M., and Mahoney, J. G., 2020. Beyond digital orientalism: exploring China as cyberpower. Journal of Chinese Political Science. Forthcoming.

Ng, J.Q., and E.L. Han. 2018. Slogans and slurs, misogyny and nationalism: A case study of anti-Japanese sentiment by Chinese netizens in contentious social media comments. International Journal of Communication 12: 1988–2009.

Nyíri, P., J. Zhang, and M. Varrall. 2010. China’s cosmopolitan nationalists: “Heroes” and “traitors” of the 2008 olympics. China Journal 63: 25–55.

Pan, G., and A. Korolev. 2021. The struggle for certainty: Ontological security, the rise of nationalism, and Australia-China tensions after COVID-19. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (1): 115–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09710-7.

Repnikova, M., and K. Fang. 2018. Authoritarian participatory persuasion 2.0: Netizens as thought work collaborators in China. Journal of Contemporary China 27 (113): 763–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1458063.

Rich, M. 2006. James Frey and his publisher settle suit over lies. The New York Times, 7 Sept. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/07/arts/07frey.html.

Schlæger, J., and M. Jiang. 2014. Official microblogging and social management by Local Governments in China. China Information 28 (2): 189–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X14533901.

Schneider, F. 2018. Mediated massacre: Digital nationalism and history discourse on China’s web. The Journal of Asian Studies 77 (2): 429–452. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911817001346.

Shen, S., and S. Breslin, eds. 2010. Online Chinese nationalism and China’s bilateral relations. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Shirk, S. 2007. China: Fragile superpower. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shirky, C. 2011. The political power of social media. Foreign Affairs 90 (1): 28–41.

Stockmann, D., and M.E. Gallagher. 2011. Remote control: How the media sustain authoritarian rule in China. Comparative Political Studies 44 (4): 436–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414010394773.

Su, R., and W. Shen. 2021. Is nationalism rising in times of the COVID-19 pandemic? Individual-level evidence from the United States”. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (1): 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09696-2.

Tang, W. 2016. Populist authoritarianism: Chinese political culture and regime sustainability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tang, W., and B. Darr. 2012. Chinese nationalism and its political and social origins. Journal of Contemporary China 21 (77): 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2012.684965.

Tatlow, D. K. 2013. True or false? The tussle over Ping Fu’s memoir. The New York Times, 25 Feb. Available at https://cn.nytimes.com/china/20130225/c25tatlow/dual/.

The Center on Religion and Chinese Society at Purdue University. 2016. Purdue Survey of Chinese Students in the United States: A General Report. Available at https://www.purdue.edu/crcs/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/CRCS-Report-of-Chinese-Students-in-the-US_Final-Version.pdf.

Wang, Z. 2008. National humiliation, history education, and the politics of historical memory: Patriotic education campaign in China. International Studies Quarterly 52: 783–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2008.00526.x.

Wang, Z. 2021. From crisis to nationalism?: The conditioned effects of the COVID-19 crisis on neo-nationalism in Europe. Chinese Political Science Review 6 (1): 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-020-00169-8.

Wang, Z., and Y. Tao. 2021. Many nationalisms, one disaster: Categories, attitudes and evolution of Chinese nationalism on social media during the COVID -19 pandemic. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (3): 525–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09728-5.

Wu, L., M. Liu, L. Wang, J.M. Pu, and J. Wang. 2013. The bent and broken truth: A pathological analysis of Ping Fu’s rags-to-riches stories. North Charleston: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Reform.

Wu, X. 2007. Chinese cyber nationalism: Evolution, characteristics, and implications. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Xiao, Q. 2019. The road to digital unfreedom: President Xi’s surveillance state. Journal of Democracy 30 (1): 53–67.

Xu, X. 2019. Protests sow division among Vancouverites whose roots are either in Hong Kong or Mainland China. The Globe and Mail, 27 Sept. Available at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/british-columbia/article-protests-sow-division-among-vancouverites-whose-roots-are-either-in/.

Yang, G. 2003. The internet and the rise of a transnational Chinese cultural sphere. Media, Culture & Society 24 (4): 469–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437030254003.

Yang, G. 2009. The Power of the internet in China: Citizen activism online. New York: Columbia University Press.

Yang, G. 2021. Online lockdown diaries as endurance art. AI & Society. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01141-5.

Yang, H., and D. Zhao. 2015. Performance legitimacy, state autonomy and China’s economic miracle. Journal of Contemporary China 24 (91): 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2014.918403.

Yang, L., and Y. Zheng. 2012. Fen Qings (Angry Youth) in contemporary China. Journal of Contemporary China 21 (76): 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2012.666834.

Yang, Y., and X. Chen. 2021. Globalism or nationalism? The paradox of Chinese official discourse in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (1): 89–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09697-1.

Zhao, S. 1998. A state-led nationalism: The patriotic education campaign in post-Tiananmen China. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 31 (3): 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(98)00009-9.

Zhao, X. 2021. A discourse analysis of quotidian expressions of nationalism during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chinese cyberspace. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (2): 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09692-6.

Zheng, Y. 1999. Discovering Chinese nationalism in China: Modernization, identity, and international relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

I would extend my special thanks to Amanda Joffe who helped code the data as well as Tyler Richards and Jenica Moore, who also provided excellent research assistance. I am extremely grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their critical constructive comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Notes on Coding Process and Some Coding Results

A research assistant who is a native English speaker, and I, a native Chinese speaker, have done the coding together. The overall tone of a review is coded as negative or positive based on whether it praises or criticizes the memoir or Ping Fu. The coding was straightforward because Amazon has five-star rating scale (with one-star being the poorest and five-star being the best). We coded four- or five-star reviews as positive and one- or two-star reviews as negative, with the exception of the 15 reviews in which the reviewers assigned five or four stars to avoid censorship (Amazon allegedly removed some one-star reviews) and to poison the five-star reviews—these reviews are easy to identify, with many directly calling Fu a liar. We coded the 19 three-star reviews together after deliberation, forcing them into the positive or negative category to keep the analysis concise.

Coding reviewers’ identity was less straightforward. We only coded a reviewer as Chinese if one (1) revealed Chinese identity (e.g., I grew up in China or my parents suffered during the Cultural Revolution) or (2) had a Chinese-like username (e.g. Zhang; Chen) and did not explicitly deny the Chinese identity. Reviewers with typical non-Chinese names and no signs of Chinese identity were coded as non-Chinese. Those with undistinguishable usernames and no identity information were coded as unidentifiable. A research assistant (native English speaker) and I (native Chinese speaker) coded 500 reviews independently (inter-rater agreement=92.99%; kappa value=0.8453; the inter-coder reliability is calculated using the weighted kappa command in Stata since there are two coders and the variable has three categories); we then deliberated on discrepant results to reach a consensus and coded the rest of the reviews together. While there is no way to verify the identity of the reviewers (having a Chinese-like username does not mean that one is a Chinese), I believe the results are sufficiently reliable. First, we do not see any reason for either side to hide the identity in the debate. Second, observation of mobilization on overseas Chinese forums like mitbbs.com provides circumstantial evidence of Fu’s criticizers being overwhelmingly Chinese.

Note that we coded 286 out of 913 reviews (or 31 percent) as from unknown reviewers out of the maximum level of caution because they provide little identity information. In fact, such reviews are significantly shorter, with the medium word count being 47, as compared to 71 and 83 for reviews by non-Chinese and Chinese reviewers, respectively. The unknown reviews are likely by Chinese reviewers as they (1) came out during the brief period of overseas Chinese mobilization on forums like mitbbs.com and (2) have expressions and language signs indicating non-native speaking traits. Since the majority of these reviews are critical toward Fu (76 percent as in Table 1), I believe the relatively large number of the unknown reviews is not going to invalidate the findings and arguments.

Appendix 2: Key Word Analysis of Amazon Reviews

To capture the narratives of Chinese and non-Chinese reviewers, I conduct a computer-aided keywords analysis to identify the frequent words used by the two sides. Below I present the results. Please note that interpretation of the results is supplemented by close reading of the reviews. To keep it parsimonious, words such as “book,” “author,” “China,” and stop words are dropped.

The results, visualized in Figure 1A, confirm the observation of identify-based narrative polarization. As the left panel shows, foreign reviews are generally positive as indicated by terms like “great,” “inspiring,” “worth,” and “recommend.” While critical terms such as “negative” also appear in the panel, they only indicate the acknowledgement of the critical reviews, which were often seen as biased or state-sponsored, thus disregarded, as close analysis of the texts shows.

As the right panel shows, Chinese reviewers question the veracity of the memoir. The attitude is clearly conveyed by terms like “lies” (and lie, liar, lying), “fake,” and “fiction.” Terms such as “Suzhou,” “university,” and “English,” while seemingly neutral, are critical when put back into the context. For example, Suzhou University, Fu’s alma mater, is the place where some of Fu’s important life stories took place, which criticizers believe she has lied about, including her claims about vaginal checks, being a member of a rebellious literacy society, and writing of a thesis that caused her to be deported. Thus, “Suzhou” and “University” reflect Chinese reviewers’ effort to validate their accusation of Fu as a liar. Similarly, “English” is pivotal term because Fu claimed that she could speak only three words when she first arrived in the U. S., which was regard as another lie.

Looking at these two panels, one may find some common key words such as “life,” “cultural,” “revolution,” and “memoir.” These words reflect more what the book is about than displaying reviewers’ attitudes, thus do not manifest the contestation between Chinese and non-Chinese reviewers. Indeed, closer reading of the reviews confirms that the two sides project distinctive impressions of Fu and China. Foreign reviewers either did not engage in the debate (especially those who commented before the critical reviews), or mostly supported Fu. Chinese reviewers accused the memoir as full of lies and tried to debunk such lies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Han, R. Debating China beyond the Great Firewall: Digital Disenchantment and Authoritarian Resilience. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 28, 85–103 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-022-09812-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-022-09812-4