Abstract

We study the investment behavior of new domestic Chinese venture capital (VC) firms compared to foreign VC firms newly entering the Chinese market. Given the institutional and cultural differences or psychic distance between China and the home country of foreign VC’s, the Uppsala Model would predict that foreign VC’s will be more cautious initially than domestic Chinese VC’s and that the degree of caution will increase with the psychic distance. Our data comes primarily from Zero2IPO, which has a nearly exhaustive list of VC investments in China from 1996 to 2006. We also use country-of-origin, membership in GLOBE cultural clusters, and a broad measure of psychic distance based on institutional and cultural differences from Berry, Guillén, & Zhou (2010) and the Freedom Index to test this prediction. We find support for the hypothesis that psychic distance affects initial investment behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Uppsala Model proposes that firms expand abroad incrementally, gradually committing more resources to a foreign market as they grow in experience. Consistent with Penrose’s (1959) theory of the firm, the Uppsala theory explains how a firm makes use of existing resources to expand into other economically profitable activities (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). The Uppsala Model deals partly with how a firm first begins business activities in a foreign market and partly with how it behaves after it has already begun its activities in that market. It is one of the most widely-referenced theories in international business and research has shown evidence to support the validity of the model in a number of countries (Andersson, 2004; Bilkey & Tesar, 1977; Cavusgil, 1980; Karafakioglu, 1986; Vahlne & Johanson, 2017, 2020, p. 40; Wu & Vahlne, 2020).

Researchers have found support for the idea that firms expand abroad with a preference for countries for which culture, language, and other factors of psychic distance present less of a hindrance to the flow of information (Carlson, 1974; Dow, 2000; Dow & Karunaratna, 2006; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975). Psychic distance becomes less of a deterrent to international expansion as a firm gains experience and expands into similar markets (Dow, 2000; Erramilli & Rao, 1990; Liesch & Knight, 1999).

Early papers from the Uppsala school focused on incremental expansion as it relates to mode of entry into a foreign market, and this is the general focus of the theory as it has been applied (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975). The principle of incremental expansion in the model also applies to how firms behave once they have already set up their own operations in a foreign country. The model proposes that firms expand incrementally into new foreign markets (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975).

The first domestic venture capital entities in China were funded by local governments and universities. Chinese banks followed with government acting as guarantors. By the mid-1990’s, Chinese leaders, seeking to encourage venture capital investment in the development of high technology (Wang, 2007), realized that the banks and local governments could not finance startups on the scale the country needed. The industry grew slowly for about the first fifteen years (Jia, 2015), during which time domestic firms were linked to the state and often run by government employees, but began to grow rapidly from 1998 to 2001 during the Tech Boom years, especially due to the arrival of foreign venture capital firms.

The venture capital firm is a type of service firm. Internationalization of service firms is different from internationalization of manufacturing firms (Anand & Delios, 1997; Brouthers & Brouthers, 2003; Wright et al., 2005). Much of the research on the internationalization of firms focuses on manufacturing firms, but the Uppsala model proposition that firms prefer to expand into countries with which they have less psychic distance has also been supported in the case of service firms (Erramilli & Rao, 1990). Venture capital firms might be expected to behave differently from other service firms. There is a gap in the literature as to whether internationalization behavior of venture capital firms varies according to both the firm’s country of origin and the country in which the investment is made, as it does in the manufacturing sector (Wright Pruthi & Lockett, 2005).

Dai and Nahata (2016) examined syndication behaviors among venture capitalists, and argue based on their findings that “foreign VCs gain increasing familiarity with host cultures, over time, by investing in local markets, which makes them more comfortable and competent both in selecting promising investments and syndicating with local VCs.” But their research did not focus on venture capital expansion behavior as this paper does.

This paper extends the logic of the research of (Huang et al., 2023) who compared regions of China to separate countries and found that, within China, institutional distance has a dampening effect on the likelihood of venture capital investment. This paper extends the line of thought and shows that institutional distance between actual countries, the host country of the VC firm and China, predicts less aggressive investment behavior.

Just as psychic distance affects the mode and pace of entry into a foreign market, it affects the conduct of foreign firms once in the market. As their experience grows, they would be expected to commit more resources to expansion and growth. In the special case of the opening of a new market for an industry, the Uppsala model would predict that foreign firms expand less aggressively than local firms do. Further, the greater the psychic distance for the foreign firm, the less aggressively it would be expected to expand. The opening of the Chinese venture capital industry offers an opportunity to test that prediction.

Research questions

We examine the patterns of investment of foreign and domestic venture capital firms in mainland China, comparing foreign venture capital firms to domestic Chinese venture capital firms, and comparing foreign firms to one another based on measures of psychic distance, operationalized as cultural or institutional measures of distance. Though this research will focus on the application of the Uppsala model to venture capital in China, it will also provide insight into the extent to which the model applies to the business activities of new foreign versus new local firms in a market. The research will therefore be concerned with the following broader questions.

-

1.

Does institutional distance between a venture capital firm’s country of origin and the country in which it invests affect venture capital behavior?

-

2.

Does institutional distance between the venture capital firms’ country of origin and the target country predict the pace at which venture capital firms commit to investing in the venture capital market in the target country?

-

3.

Do venture capital firms whose countries of origin are institutionally distant from the target country quickly ramp up investment to match that of firms whose countries-of origin are less institutionally distant after a brief period of time?

Literature review

The Uppsala model

This research draws from the Uppsala Model of internationalization. The Uppsala model is described in studies from the 1970’s and is named for the city in which some of the researchers were based (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975). The predominant view of researchers before this theory rose in popularity was that firms chose their mode of entry into a market after analyzing the market characteristics in light of their costs and resources (Hood & Young, 1979; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2009). Based on an examination of case studies of four Swedish firms, Johanson and Vahlne (1977) argued for an ‘incremental internationalization view’ of the process of firms expanding abroad.

The Uppsala school of thought builds on Penrose’s (1959) theory of the growth of the firm and the work of Aharoni (1966) and Cyert and March (1963). Knowledge of a target market is a firm resource. According to the Uppsala model, a firm increases commitment and expands operations in a new market as it increases its knowledge of the market. The theory makes use of Penrose’ understanding of experiential knowledge, which is difficult or impossible to transfer but which results in changes as the firm adapts to its environment. Aharoni (1966) wrote of firms making commitments in a foreign market in response to the environment. Cyert and March (1963) proposed that organizations engage in problemistic search to find solutions to problems. This is consistent with the idea that firms learn as a result of problems encountered as they engage in current activities, and is in line with the thinking of the Uppsala model (Forsgren, 2002).

The Uppsala Model proposes that firms expand abroad slowly, partly because of a lack of market knowledge, which produces uncertainty (Hörnell et al., 1973; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). Uppsala theorists argue that this theory is still valid even if some of the steps to internationalization presented in the empirical evidence in the 1977 paper are not valid in every case or have changed over time (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009).

Psychic distance and the liability of foreignness

Beckerman (1956) originally introduced the use of the term ‘psychic distance’ to explain factors besides physical distance that might systematically affect trade flows. He described psychic distance as the difficulty of personally contacting and cultivating sources for foreign trade.

According to the original Uppsala theory, the challenges foreign firms face in learning how to operate in new markets is related to the degree of psychic distance between the firm’s home country and the new market. Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) define psychic distance as “factors preventing or disturbing the flow of information between firm and market. Examples of such factors are differences in language, culture, political systems, level of education, level of industrial development, etc.” or as “factors that make it difficult to understand foreign environments” (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). Johanson and Weidersheim-Paul (1975) suggested that membership in the British Commonwealth may reduce psychic distance even though some of these countries are geographically very distant. Subsequent research has supported the theory that previous colonial ties do reduce psychic distance (Dow & Karunaratna, 2006). Uppsala researchers eventually included such factors as differences in language and culture and the existence of prior trade channels as measures of psychic distance (Nordstrom & Vahlne, 1994).

Johanson and Vahlne (2009) later explained that the concept of psychic distance had its roots in the concept of the ‘liability of foreignness’ (Hymer, 1976) and that larger psychic distance corresponded with a larger liability of foreignness (Zaheer, 1995). Hymer (1976) listed various challenges a firm would face as a new entrant in a foreign market, including the cost of acquiring information, differential treatment from the home country government, buyers, and suppliers when compared to local firms and differential treatment from its own country of origin such as prohibitions to operate or taxes. Hymer’s theory proposed that a foreign firm must have a firm-specific advantage to justify expanding abroad, since the firm-specific advantage would be needed to overcome the challenges firms face in overcoming costs associated with foreignness (Hymer, 1976).

Zaheer (1995) categorizes these costs into four categories: “(1) costs directly associated with special distance, such as the costs of travel, transportation, and coordination over distance and across time zones; (2) firm-specific costs based on a particular company’s unfamiliarity with and lack of roots in a local environment; (3) costs resulting from the host country environment, such as the lack of legitimacy of foreign firms and economic nationalism; (4) costs from the home country environment, such as the restrictions on high-technology sales to certain countries imposed on U.S.-owned MNEs.”

Not all of Zaheer’s costs are particularly important for venture capital firms. VC firms can simply send expert investors to work in the foreign country without the same degree of concern for logistics and the amount of travel needed for a manufacturing firm. Categories (2) and (3) could be applicable to foreign venture capital firms operating in a foreign market. In the Chinese context, venture capital firms could face difficulties from not knowing or understanding how social networking operates in China and from a lack of relationships with government officials and businesses. In fact, research has shown that in China, there are government officials who are worried about “labor exploitation” who oppose venture capital because they are concerned it undermines the socialist system (Ahlstrom et al., 2007). Category (2) includes a lack of roots in the local environment. We could argue that this also includes a lack of understanding of the local culture and the institutional context.

Cultural distance

The concept of psychic distance in the early Uppsala literature was an ill-defined grab bag of potential non-geographic distance factors. This topic was largely unexplored in the research at that time. Over time, numerous papers were written to explore ways of measuring more specific categories of non-geographic distance. Researchers have found ways of measuring cultural distance and various measures of institutional distance.

Cultural distance is perhaps the most commonly used non-geographic measure of distance in the international business literature. Kogut and Singh (1988) used Hofstede’s (1980) cultural dimensions in a test of entry modes of foreign firms into the United States. Their results showed a relationship between a measure of cultural distance developed from Hofstede’s dimensions and the choice of whether to enter the United States market by joint venture, wholly owned subsidiary, or acquisition. Many subsequent papers have been written using the same technique for measuring cultural distance (Shenkar, 2001).

Uppsala researchers have used a measure of cultural distance similar to Kogut and Singh’s that collapses the Hofstede measures into one number as a measure of psychic distance (Nordstrom & Vahlne, 1994). The use of Kogut and Singh’s measurement has been criticized because it mathematically reduces Hofstede’s dimensions into one score, which ignores the fact that some cultural dimensions may be much more useful than others (Shenkar, 2001). Hofstede himself warned against the use of overall differences among the dimensions because the differences between certain dimensions are not linearly additive (Hofstede, 1980). One study found that though the Kogut and Singh measure yielded significant results, only three cultural dimensions contributed to joint venture survival (Barkema & Vermeulen, 1997).

More recently, the GLOBE project has produced a large amount of research on cultural differences. Building on the work of Hofstede, 170 researchers from 62 cultures surveyed over 17,000 managers in 951 organizations regarding their cultural practices and values. This work was called the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Project (GLOBE). The GLOBE dimensions are Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Institutional Collectivism, Gender Egalitarianism, and Assertiveness. GLOBE studies divided the 62 cultures into 10 cultural clusters: Confucian Asia, Southern Asia, Latin America, Nordic Europe, Anglo, Germanic Europe, Latin Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East (House et al., 2004).

The Confucian Asian cluster includes the Chinese societies of Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong where guanxi and other aspects of Chinese culture are important for doing business (Bruton & Ahlstrom, 2003; Chow, 2007; Li et al., 2007; Ong & Nonini, 1997). We should therefore expect these societies to be closer, culturally, to mainland China than the other societies in the Confucian Asian cluster.

Institutions and psychic distance

Psychic distance between foreign firms and the Chinese market can be viewed in terms of institutional differences. There may be a vast difference between the institutional environments of a firm’s home country and the institutional environment of a host country. Institutional distance is a broad concept since a wide variety of things can be categorized as institutions. Much of the research on venture capital in emerging markets like China takes an institutional approach, e.g., Bruton and Ahlstrom (2003). It is therefore important to consider the topic from an institutional perspective.

According to institutional theorist Douglass North, institutions are the ‘rules of the game in a society.’ (North, 1990, p. 2). North argues that institutions are ‘humanly devised constraints that structure human interactions,’ and that these constraints evolve over time (North, 1991). People impose these structures on their own lives They develop beliefs about them and they perceive these restraints as reality (North, 2006). Institutions serve to reduce uncertainty. They benefit us by providing a stable structure for human interaction (North, 1990; Peng, 2003).

There are multiple ways to categorize institutions. North (1990) emphasizes the distinction between formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions include regulatory structures, laws, courts, agencies, interest groups, professions, and the media (Oliver, 1991; Zacharakis et al., 2007). Informal institutions are manifested in language, beliefs, and physical artifacts. (Scott, 1995) categorizes institutions into three ‘pillars’: regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive. Regulatory institutions include laws that influence human behavior and governmental organizations. Normative institutions include norms, values, and beliefs and basic assumptions about human nature shared by members of a society. Cultural-cognitive institutions include subconsciously accepted traditions, rules and customs, and commercial conventions that are taken for granted (Bruton et al., 2004; Scott, 2002). Cultural distance, therefore, can be seen as an aspect of institutional difference.

Institutional distance has become an important construct for internationalization research since the mid-1990s when the concept was introduced into the literature (Kostova, 1997) and has become widely used in international type of research that deals with ‘distance’ (Kostova et al., 2020; da Silva et al., 2023). Measures of institutional distance then can provide a broader measure of psychic distance than cultural distance measures. Berry et al. (2010) presented a diverse set of distance measures examining a wide variety of institutional distance factors including economic, financial, political, administrative, and cultural. Measures of institutional distance can also be derived from the Heritage Foundation’s Freedom Index (www.heritage.org/index/) which provides scores for countries on the following dimensions: property rights, freedom from corruption, fiscal freedom, government spending, business freedom, labor freedom, monetary freedom, trade freedom, investment freedom, financial freedom. Previous research has found support for the idea that variables in the Freedom Index can affect the speed of internationalization (Felzensztein et al., 2022).

In addition to Kogut and Singh’s (1998) work on cultural distance as a determinant of entry mode choice, numerous other articles have used the broader concept of institutional distance as it relates to entry mode choice (Delios & Henisz, 2003; Schwens et al., 2011; da Silva et al., (2023; Vouga Chueke & Mendes Borini, 2014; Wu & Deng, 2020). These distance measures have also been used in relation to firms’ other ownership decisions and relationships (Chikhouni et al., 2017; Dunning & Lundan, 2008; Peng, 2003; da Silva et al., (2023).

The overlapping categories of cultural, institutional, and psychic distance are important concepts in regard to internationalization in research that relates to both venture capital and China-specific investment behaviors and firm performance. Using Chinese data, research has shown that trust may mitigate the negative effects of both cultural and geographic distance, in regard to VC syndication behavior (Du, 2009; Hain et al., 2014). Using data on transactions within China, Huang, Qiu, Wu, & Yao (2023) found that trust had a moderating effect on institutional distance. Research on SMEs in China has also shown that certain institutional factors can override the effects of psychic distance (Yan et al., 2020).

Institutional challenges for venture capital in China

Guanxi is a Chinese institution. Literally, the word refers to “a relationship between objects, forces, or persons.” It is believed that, in China, guanxi relationships substitute for the formal institutions found in countries with stronger formal economic institutions (Xin & Pearce, 1996). One sociologist commented, “In essence, the Chinese bureaucracy inhibits action while Guanxi facilitates action” (Alston, 1989). Guanxi relationships are essential in helping new ventures achieve success in China, (Guo & Miller, 2010; Zhao & Ha-Brookshire, 2018), and they can help venture capital firms as they conduct due diligence and interact with Chinese firms (Bruton & Ahlstrom, 2003; Chen, 2020). Many venture capital firms have found that guanxi relationships are necessary to properly monitor a firm after an investment (Young et al., 2011).

It stands to reason that foreign venture capital firms may initially act slowly in the Chinese market as they develop guanxi relationships. Firms from the Confucian Culture sector may have an advantage over other foreign firms, since they may have to spend less time learning the intricacies of developing a guanxi network.

Any treatment of China’s institutional context must take into account that China is a transitional economy, changing from a communist form of government toward free markets. Communist countries have historically had bureaucratic rules that are hostile toward market competition. This leads parties interested in conducting market transactions to do so through relationship-based exchanges. The lack of institutions to support venture capital in China creates a situation where there can be great psychic distance between a venture capital firm from a home country with strong regulatory institutions and the Chinese market.

It is important to recognize that the institutional environment around venture capital in China is evolving. Though corporate governance regulations in China are still weak, they are improving (Ahlstrom et al., 2007). Standards and professionalism in the venture capital industry are improving (Ahlstrom et al., 2007), and the government has passed regulations that have increased stability for the venture capital industry (Burke, 2003). Thus, the psychic distance related to institutional differences is likely to be decreasing over time.

Local investment

Venture capital firms have traditionally invested close to their home offices. One venture capitalist commented that he liked to keep his investments close enough so that they were all within a half an hour drive away or less (Brown, 2004). But in the late 1990’s, venture capital firms began to make cross-border investments (Guler & Guillén, 2010a). Theoretically, a venture capital firm could invest in a foreign country without setting up shop in that country. However, part of the formula for success that VCs follow is to exercise a measure of control over and offer guidance to the managers of the firms in which they invest (Gompers & Lerner, 2001). It may be difficult to do this from a foreign location. Venture capital firms also provide industry, managerial or technical expertise to managers of the Chinese firms in which they invest (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2006; Ahlstrom et al., 2007). This requires a local presence. Therefore, foreign venture capital firms typically set up a local office in the country in which they seek to make investments.

Internationalization of service firms

The Uppsala Model originated from examining the export patterns of manufacturing firms. Manufacturing or production was explicitly mentioned as a part of the original establishment chain. Internationalization of service firms is somewhat different from the internationalization of manufacturing firms (Anand & Delios, 1997; Wright Pruthi & Lockett, 2005). Among service firms, foreign direct investment is the entry mode of choice for services that are “people-embodied,” that require a high degree of interaction between producers and consumers (Buckley et al., 1992). A soft drink manufacturer can export its physical products across borders, but a legal firm’s services are people-embodied, and it could be difficult for a legal firm to serve its client’s needs. Venture capital firms are people-embodied firms. It is important for a representative of the firm to meet managers of potential investments, conduct due diligence, and monitor investments.

The Uppsala model and information asymmetry

Building on the research of Akerlof (1970), Amit et al. (1998) argued that the reason venture capital firms exist is because they have an advantage at overcoming information asymmetry for certain types of investments. An understanding of the culture of China, how to operate in the institutional environment, and the development of guanxi relationships with certain actors in the environment are all necessary for a venture capital firm to be able to evaluate potential target investments and to develop the ability to overcome the problem of information asymmetry. While foreign VCs expanding into China will likely have relevant experience, these firms will require some time operating in China before their managers develop the market knowledge needed to adequately evaluate and monitor investments. Consistent with the Uppsala model, we can expect that foreign venture capital firms will be more conservative in regard to their business activities in China initially when compared to local firms, but make more commitment decisions as time goes on. Previous research indicates that the Uppsala model may partially explain internationalization, (de Mello et al., 2019), and we may expect this to be the case with venture capital firms.

In regard to information asymmetry, there may be areas in which foreign venture capital firms are superior at overcoming information asymmetry. Firms with experience in a particular field of technology or service that is well-developed in the firm’s home country may have an advantage in understanding the process of bringing a product or service to market in a new developing economy.

Experience: a potentially confounding effect

One of the potential confounding effects that comes from comparing new foreign market entrants to new domestic entrants in a new market is the fact that foreign firms will generally have much more experience in the industry than the new domestic firms. If local Chinese venture capital firms raise funds or invest more aggressively than foreign firms, it may be that the Chinese firms do so based on a lack of sophistication and experience. In order to account for this possibility, we can compare the investment behavior of various groups of foreign firms. Considering that Taiwan, Singapore, and Japan all have well established venture capital industries (Ahlstrom et al., 2007; Bruton et al., 2004) we can assume that the decisions of venture capital firms expanding into China from these countries do not make their decisions based on a lack of experience and sophistication.

Similarly, foreign venture capital firms with prior experience investing abroad may be more likely to invest aggressively when entering a new foreign market than foreign VC firms without such experience. We attempt to control for prior foreign investment experience in our investigation.

Hypotheses

According to the Uppsala Model, we can expect that new domestic firms will make decisions more quickly and behave more aggressively initially when compared to foreign firms new to the market. There are numerous ways in which a venture capital firm can behave aggressively in its fundraising, investing, portfolio management, and exit strategies. Foreign venture capital firms new to the Chinese market must operate cautiously to navigate in the economic environment. They may therefore be more conservative about how frequently they invest when they first enter the market. Domestic venture capital firms can afford to be more aggressive if they are comfortable with the environment and have strong guanxi relationships with important contacts to help them navigate the weak institutional landscape. The domestic venture capital firm may have learned of many good investments over the years, and be ready to invest in many of them as soon as the firm begins operations. Over time, as foreign venture capital firms become more accustomed to the market and the local culture and develop guanxi relationships, they can invest more aggressively, as well.

This research examines three hypotheses about the effect of psychic distance on VC investing. We observed that foreign firms were more aggressive than Chinese firms in terms of the number of investments in the Chinese market. But we suggest that, there is a liability of foreignness that results in institutionally distant firms behaving less aggressively than they otherwise would. When we account for the fact that foreign firms are more aggressive in terms of total numbers of investments made, we can still expect that VC firms coming from culturally and institutionally distant countries will invest less aggressively in a relative sense. We investigate this by comparing behavior when first entering the market to their later behavior.

Hypothesis 1

Foreign venture capital firms invest less aggressively when first entering the Chinese market when compared to domestic Chinese firms.

Hypothesis 2

Venture capital firms that are from countries outside of the Confucian Asian cultural cluster invest less aggressively when first entering the Chinese market when compared to firms from the Confucian Asian cultural cluster.

Hypothesis 3

Venture capital firms that are more institutionally distant are less likely to invest aggressively when first entering the Chinese market when compared to less institutionally distant firms.

To test these hypotheses, we propose examining the aggressiveness of firm investment behavior by looking at the relative frequency of investments in early versus later periods. Less aggressive investment behavior would be indicated by a higher percentage of investments made in later periods.

Data

The data on venture capital activity in China was taken primarily from the Zero2IPO online database which is a nearly exhaustive database of Chinese venture capital and private equity activity in China. Country-of-origin data was taken from the Zero2IPO website, from the 2010 edition of China Venture Capital & Private Equity Directory, a publication put out by Zero2IPO, from target or investment firm websites or other websites. Our data covers the time period from 1995 until the last month of 2006. This time period covers the opening of China to foreign venture capital and the early development of the Chinese VC industry. It allows for comparing the early growth of domestic VC firms with the entry and growth of many foreign firms, all new to the market. This also corresponds to the initial time period of venture capital international expansion.

Table 1 presents available information regarding country of origin and information regarding amounts each country’s firms invested. The data covers 735 VC firms and 1610 transactions for firms for which country-of-origin data is available. These firms invested in 2549 target firms. In emerging economies, the terms ‘venture capital’ and ‘private equity’ are often used interchangeably (Ahlstrom et al., 2007; Bruton et al., 2004) and the data source we used grouped them together as one.

Institutional distance measures between China and the country of origin for venture capital firms were derived from the work of Berry et al. (2010). This research presented a diverse set of distance measures examining a wide variety of institutional distance factors including economic, financial, political, administrative, and cultural. We also use an institutional distance measure derived from the Heritage Foundation’s Freedom Index (www.heritage.org/index/) which provides scores for countries on the following dimensions: property rights, freedom from corruption, fiscal freedom, government spending, business freedom, labor freedom, monetary freedom, trade freedom, investment freedom, financial freedom. Previous research has found support for the idea that variables in the Freedom Index can affect the speed of internationalization (Felzensztein et al., 2022).

Specific information regarding the sources used for the data by Berry et al. (2010). can be found in Table 2.

Methods

Exploratory factor analysis and results

The institutional variables from The Heritage Foundation and from Berry et al. (2010). are highly correlated with one another. Stepwise regressions with the variables from these sources were run with the dependent variables described in Table 2. Many variables were significant and explained a small amount of the variance, and variables were highly correlated with one another, and used together resulted in multicollinearity. We decided to perform an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the institutional distance variables using the SPSS statistical software package. The EFA method we chose was Principal Axis Factoring, a method of factor analysis which does not require that variables be normally distributed (Costello & Osborne, 2005). This was performed on standardized versions of the variables. Both the eigenvalue-greater-than-one method and the scree plot method returned a two-factor solution (Courtney & Gordon, 2013).

The EFA discovered two underlying factors, which we have labeled Institutional and FINECON. The FINECON variable makes use of the variables Economic, Financial, Administrative, and Freedom_Index. The variable Institutional_ uses the loadings from the other variables: Culture, Demographic, GlobalConnectedness, and Political Distance. The other variables collectively weigh heavily in the factor named Institutional_.

The Cronbach Alpha for the factory analysis is 0.94 indicating a high level of internal consistency. Tables 3 and 4 present Pearson Correlations and descriptive statistics. Table 5 presents the results of the EFA (See Table 6).

Regression models and results

Hypotheses were tested using a series of regression models with the SPSS statistical software package. The statistical models examine the percentage of investments that occurred in each year compared to all the firm’s investments throughout the dataset. These models examine data at the firm-year level. Foreign firms tend to be more aggressive in terms of number of investments made. These models allow us to account for this fact and to determine whether, accounting for the overall aggressiveness of foreign firms, they ramp up the frequency of investment more slowly as institutional distance increases. This tests whether there is an overall trend of foreign and culturally or institutionally distant firms investing a smaller percentage of their number of overall investments in earlier years than later years. Firm-level models compare year one to later years, while firm-year models look for an overall trend. The model also contains control variables for each calendar year. This allows for readers to observe for patterns during boom and bust years, an area of potential further research (Clau & Krippner, 2019, p. 1439; Madhavan & Iriyama, 2009).

Results for statistical models

Models 1 through 8, shown in Table 7, are designed to test the effects of country of origin, cultural distance, and institutional distance on frequency of investment in the China market over time. Tables 8 and 9 display descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations used for these models. The dependent variable for each of these models is called FreqInvYr, which examines the data at the firm-year level, measuring the percentage of the number of investments made by a VC firm in a given year of their investment period.

In order to test our hypotheses, each model includes an interaction effect for the InvYear and either a country category dummy variable or institutional distance measure. One might argue that venture capital internationalization may have been affected by historical economic issues like the Dot Com Bubble. Using multiple regressions with the year variable allows for observation of patterns that occurred at important points along the time line, unlike using longitudinal analysis. Each of these models includes dummy control variables for the calendar year in which investments were made. Each of these models also makes use of a variable InvYear, which is the year number for the firm, counted as a 365 day period, with year one counted with a value of one, year two as a value of two and so on. Dummy control variables for calendar years are identified as ‘Y’ followed by the number for the calendar year the variable represents with the exception of Y1995, which serves as the reference category. Initial runs of statistical models showed calendar year variables for 1996 to 2006, but these models all showed severe multicollinearity between variables Y2006 and Y2007. Therefore, Y2007 was removed from all models as they are presented.

Models 1 and 2 are designed to test Hypothesis 1 and include the variable ChinaDUM as an independent variable along with the InvYear variable and eleven calendar year control variables. The interaction effect of ChinaDUM * InvYear allows us to see the effect of whether the firm is from China or not on FreqInvYr for each year the firm has investment activity in the Chinese market. Model 1 includes the control variable Prior_Inv.

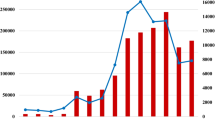

Models 1 and 2 support Hypothesis 1 with negative and statistically significant coefficients on the interaction term. Interaction effects make an equation more complicated and difficult to understand. Graphs are a useful tool for understanding interactions (Keith, 2014, p. 133). Graphs were developed using SPSS and MSPaint. Figure 1 presents the interaction effect graphically. This graph shows the FreqInvYr versus the investment year. The lines graphed show the best linear fit for China versus Foreign firms (ChinaDUM equals 1 or 0). The slope of the line for China firms is steeper downward than for foreign firms, indicating that foreign firms stretch the percentage of the amount they invest more across the years, which is consistent with Hypothesis 1. Similar graphs were created for other categories of firms as shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

Models 3 and 4 use the same equation as those used for Models 1 and 2 except with ConfucianAsia (Confucian Asia) instead of ChinaDUM as an independent variable along with the interaction effect ConfucianAsia * InvYear. In both models, the interaction effect is negative and not statistically significant. Model 3 adds the variable Prior_Inv to control for the number of prior foreign investments. Figure 2 illustrates the interaction effect. The variables of interest were not shown to be significant in these models, indicating that Hypothesis 2 is not supported.

Models 5 and 6 make use of the variable Institutional_ and the interaction effect Institutional_ * InvYear along with the calendar year variables. Model 5 adds Prior_Inv as a control variable. In both models, the significant interaction effect provides evidence for support of Hypothesis 3. Both models are significant and each explain an R2 of 0.27 and an adjusted an R2 of 0.26. In both models the highest VIF value is 1.44 for any variable.

Figure 3 graphically presents the interaction effect for Models 5 through 6. The firms are divided into three groups, high, medium, and low institutional distance. The “low” group is China, and has a value of 0 for distance. These firms invest the highest percentage of overall investment in the first year. The slope of the line drops off more sharply than it does for higher distance firms, which is consistent with Hypothesis 3. In both models, the variables Institutional_, InvYear and their interaction effect were statistically significant, offering support for Hypothesis 3. Interestingly, the slope of the line for very distant firms is steeper than the slope of the line for medium distance firms. But the number of medium distance firms was relatively small, 35 out of 935 firms for Figs. 3 and 15 out of 935 for Fig. 4.

Models 7 and 8 make use of the variable FINECON and the interaction effect FINECON * InvYear along with the calendar year variables. Model 7 includes Prior_Inv as a control variable. In both models, the significant interaction effect provides additional evidence for support of Hypothesis 3, and both FINECON and InvYear are also significant. Both models are significant and each explain an R2 of 0.27 and an adjusted an R2 of 0.26. In both models the highest VIF value is 1.44 for any variable in either of the models.

Figure 4 graphically presents the interaction effect for variables in Models 7 and 8. The firms are divided into three groups, high, medium, and low institutional distance. The “low” group is China, and has a value of 0 for distance. These firms invest the highest percentage of overall investment early in the process. The slope of the line drops off more sharply than it does for more distant firms, which supports Hypothesis 3.

We hypothesized that while foreign firms generally invested more often and in larger amounts, domestic Chinese firms would be more aggressive venture capital investors than foreign firms, investing more quickly than their foreign counterparts. Domestic Chinese firms did tend to invest relatively more frequently in early years compared with foreign firms. Foreign firms also tended to invest more aggressively initially if they were less institutionally distant from China on both the FINECON and Institutional_ factors. Overall, we found relatively weak support for the hypothesis that Chinese firms would invest more aggressively earlier on than foreign firms. We also found relatively weak support for the hypothesis that more institutionally distant foreign venture capital firms would be initially less aggressive because of cultural distance and the liability of foreignness.

Discussion

Theoretical implications

The use of cultural distance measures has a long history in internationalization literature. Kogut and Singh’s (1988) measure, based on Hofstede’s (1980) research, has been a popular tool for measuring psychic distance. This study goes beyond the use of a simple cultural or legal (Cumming et al., 2006) measurement of distance between countries. It makes use of a broad array of institutional measures from Berry et al. (2010). Use of institutional measures provides a broader range of differences that better capture psychic distance. This research contributes two potential institutional factors that may explain internationalization behavior, including one factor that is comprised of Financial, Economic, and Administrative distance.

Within the research that focuses on venture capital internationalization into developing economies such as China, a recurring theme is the idea that the venture capital industry is shaped by the institutional environment of the host country (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2006; Drover et al., 2017; Guler & Guillén, 2010b; Lerner & Tag, 2013). One of the difficulties with institutional theory is that institutions can be difficult to quantify and measure. The use of institutional distance measures as a means of predicting the behavior of venture capital firms fits nicely with the institutional approach to venture capital found in the literature. This study contributes to the venture capital internationalization literature by demonstrating that measures of institutional distance do predict some small effects of the behavior of venture capital firms in a developing economy such as China.

This research contributes to the Uppsala model and liability of foreignness literature by examining whether psychic distance can predict the behavior of a firm as it continues its operations in a host country. By showing that psychic distance can affect the investment behavior of venture capital firms, we find some support for the use of the Uppsala Model to explain venture capital internationalization, but only weak support that explains a relatively small amount of the variance in the data. A contribution of this paper is that it shows the applicability of the Uppsala Model of incremental expansion to international VC expansion behavior as it relates to the pace at which investments are made after VC firms enter a foreign market.

A limitation of this research is that the data do not capture the length of time a VC firm may spend between its initial investigation into the market and its first investment. It could be strengthened by examining due diligence and other activities that occur before firms begin investing in the market. Also, future research in this area would benefit from considering the real experience of managers in venture capital firms rather than treating experience investing in foreign markets as a firm-specific trait. Another area for research is to determine whether investment behavior of firms of varying institutional distance predicts venture capital success as measured by acquisitions, IPOs, or other measures.

The research was conducted with the understanding that foreign venture capital firms are generally more aggressive than local Chinese firms. Part of the aggressiveness of these firms may be explained by the experience of their managers in the venture capital industry. In an industry once so closely associated with the United States, firms from the United States, and even other western countries, may be perceived to be more credible than other firms. It is possible that some venture capital firms benefit from advantages of foreignness that partly overcome the liabilities.

Managerial implications

The managerial implications of this research are rather straightforward. Foreign managers of foreign venture capital firms should realize that the pace at which they can ramp up their activities in a foreign market such as China is related to a number of institutional factors that are quite different from those found in their own countries. Since foreign firms tend to be more aggressive in an absolute sense than domestic Chinese firms, domestic venture capital managers should be aware that firms from countries that are institutionally distant may have characteristics that enable them to quickly ramp up their operations despite institutional distance. The institutional distance factor used in this study is made up of a wide variety of institutional measures related to culture, economic, finance, administrative, global connectedness, knowledge, political and freedom distance measures. Foreign venture capital managers should consider the differences represented by institutional distance measures as they navigate the process of learning to do due diligence and engage in investment activities in foreign lands.

While this study has shown some evidence that psychic distance may slightly slow venture capital activity, institutional distance measures account for a very small amount of the variance in statistical models. Foreign venture capitalists are apparently capable of committing to the Chinese market aggressively when compared to Chinese firms, with psychic distance slowing them in a small, but statistically significant way. They were able to take their knowledge of investments in certain types of technologies, their skill at due diligence, and their ability to guide target firms in the Chinese market and expand operations more than most domestic venture capital firms during the time period represented in the data. Psychic distance between their home markets and the Chinese market has not prevented foreign firms from investing more aggressively in an absolute sense.

Data availability

This paper relied heavily on data from Zero2IPO, which is a subscription database. Due to copyright restrictions, authors may not make their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

References

Aharoni, Y. (1966). The foreign investment decision process. Cambridge, Mass.

Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. (2006). Venture capital in emerging economies: Networks and institutional change. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(2), 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00122.x.

Ahlstrom, D., Bruton, G. D., & Yeh, K. S. (2007). Venture capital in China: Past, present, and future. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(3), 247–268.

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for lemons: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 488–500.

Alston, J. P. (1989). Wa, guanxi, and inhwa: Managerial principles in Japan, China, and Korea. Business Horizons, 32(2), 26–31.

Amit, R., Brander, J., & Zott, C. (1998). Why do venture capital firms exist? Theory and Canadian evidence. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(6), 441–466.

Anand, J., & Delios, A. (1997). Location specificity and the transferability of downstream assets to foreign subsidiaries. Journal of International Business Studies, 579–603.

Andersson, S. (2004). Internationalization in different industrial contexts. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(6), 851–875.

Barkema, H. G., & Vermeulen, F. (1997). What differences in the cultural backgrounds of partners are detrimental for international joint ventures? Journal of International Business Studies, 845–864.

Beckerman, W. (1956). Distance and the pattern of Inter-european Trade. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 38(1), 31–40.

Berry, H., Guillén, M. F., & Zhou, N. (2010). An institutional approach to cross-national distance. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(9), 1460–1480.

Bilkey, W. J., & Tesar, G. (1977). The export behavior of smaller-sized Wisconsin manufacturing firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 93–98.

Brouthers, K. D., & Brouthers, L. E. (2003). Why Service and Manufacturing Entry Mode choices Differ: The influence of transaction cost factors, risk and Trust*. Journal of Management Studies, 40(5), 1179–1204.

Brown, E. (2004). The Global Startup. Forbes Global, 7(21), 40–42. buh.

Bruton, G. D., & Ahlstrom, D. (2003). An institutional view of China’s venture capital industry: Explaining the differences between China and the West. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 233–259.

Bruton, G., Ahlstrom, D., & Yeh, K. S. (2004). Understanding venture capital in East Asia: The impact of institutions on the industry today and tomorrow. Journal of World Business, 39(1), 72–88.

Buckley, P. J., Pass, C. L., & Prescott, K. (1992). The internationalization of service firms: A comparison with the manufacturing sector. Scandinavian International Business Review, 1(1), 39–56.

Burke, M. E. (2003). Venture capital options expand—a bit. China Business Review, 30(4), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

Carlson, S. (1974). International transmission of information and the business firm. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 412(1), 55–63.

Cavusgil, S. T. (1980). On the internationalization process of firms. European Research, 8(6), 273–281.

Chen, S. (2020). The Development of Venture Capital in China. In D. Klonowski (Ed.), Entrepreneurial Finance in Emerging Markets: Exploring Tools, Techniques, and Innovative Technologies (pp. 233–248). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46220-8_15.

Chikhouni, A., Edwards, G., & Farashahi, M. (2017). Psychic distance and ownership in acquisitions: Direction matters. Journal of International Management, 23(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2016.07.003.

Chow, I. (2007). Culture and leadership in Hong Kong. Culture and Leadership across the World: The GLOBE Book of In-Depth studies of 25 societies (pp. 909–946). Routledge.

Clau, I., & Krippner, L. (2019). Contemporary Topics in Finance: A Collection of Literature Surveys. Contemporary Topics in Finance: A Collection of Literature Surveys, 1–9.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

Courtney, M. G. R., & Gordon, M. (2013). Determining the number of factors to retain in EFA: using the SPSS R-Menu v2.0 to make more judicious estimations. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 18(8), 1–14. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol18/iss1/8/

Cumming, D., Fleming, G., & Schwienbacher, A. (2006). Legality and venture capital exits. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(2), 214–245.

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 2.

da Silva, F. M., Ogasavara, M. H., & Pereira, R. (2023). Institutional distances and equity-based entry modes: A systematic literature review. Management Review Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00346-4.

Dai, N., & Nahata, R. (2016). Cultural differences and cross-border venture capital syndication. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(2), 140–169.

de Mello, R. C., da Rocha, A., & da Silva, J. F. (2019). The long-term trajectory of international new ventures: A longitudinal study of software developers. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 17, 144–171.

Delios, A., & Henisz, W. J. (2003). Political hazards, experience, and sequential entry strategies: The international expansion of Japanese firms, 1980–1998. Strategic Management Journal, 24(11), 1153–1164.

Dow, D. (2000). A note on psychological distance and export market selection. Journal of International Marketing, 51–64.

Dow, D., & Karunaratna, A. (2006). Developing a multidimensional instrument to measure psychic distance stimuli. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(5), 578–602.

Drover, W., Busenitz, L., Matusik, S., Townsend, D., Anglin, A., & Dushnitsky, G. (2017). A review and road map of entrepreneurial equity financing research: Venture capital, corporate venture capital, angel investment, crowdfunding, and accelerators. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1820–1853.

Du, Q. (2009). Birds of a feather or celebrating differences? The formation and impact of venture capital syndication.

Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (2008). Institutions and the OLI paradigm of the multinational enterprise. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(4), 573–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-007-9074-z.

Erramilli, M. K., & Rao, C. P. (1990). Choice of foreign market entry modes by service firms: Role of market knowledge. MIR: Management International Review, 135–150.

Felzensztein, C., Saridakis, G., Idris, B., & Elizondo, G. P. (2022). Do economic freedom, business experience, and firm size affect internationalization speed? Evidence from small firms in Chile, Colombia, and Peru. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 115–156.

Forsgren, M. (2002). The concept of learning in the Uppsala internationalization process model: A critical review. International Business Review, 11(3), 257–277.

Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2001). The venture capital revolution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 145–168.

Guler, I., & Guillén, M. F. (2010a). Home country networks and foreign expansion: Evidence from the venture capital industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53(2), 390–410.

Guler, I., & Guillén, M. F. (2010b). Institutions and the internationalization of US venture capital firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 185–205.

Guo, C., & Miller, J. K. (2010). Guanxi dynamics and entrepreneurial firm creation and development in China. Management and Organization Review, 6(2), 267–291.

Hain, D. S., Johan, S., & Wang, D. (2014). Determinants of Cross-Border Venture Capital Investments in Emerging and Developed Economies: The Effects of Relational and Institutional Trust. Available at SSRN 2382327.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values (Vol. 5). Sage.

Hood, N., & Young, S. (1979). The economics of multinational enterprise (Vol. 16). Longman London.

Hörnell, E., Vahlne, J., & Wiedersheim-Paul, F. (1973). Export och utlandsetableringar (export and foreign establishments). Almqvist & Wiksell.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage.

Huang, Y. S., Qiu, B., Wu, J., & Yao, J. (2023). Institutional distance, geographic distance, and Chinese venture capital investment: Do networks and trust matter? Small Business Economics, 61(4), 1795–1844.

Hymer, S. (1976). The international operations of national firms: A study of direct foreign investment. MIT press Cambridge. http://teaching.ust.hk/~mgto650p/meyer/readings/1/01_Hymer.pdf.

Jia, Y. (2015). Venture capital in Chinese economic growth. The University of Texas at Dallas.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. (1977). The internationalization process of the Firm-A model of Knowledge Development and increasing Foreign Market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1411–1431.

Johanson, J., & Wiedersheim-Paul, F. (1975). The internationalization of the firm: Four Swedish cases. Journal of Management Studies, 12(3), 305–322.

Karafakioglu, M. (1986). Export activities of Turkish manufacturers. International Marketing Review, 3(4), 34–43.

Keith, T. Z. (2014). Multiple regression and beyond: An introduction to multiple regression and structural equation modeling. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315162348

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies, 411–432.

Kostova, T. (1997). Country institutional profiles: Concept and measurement. Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings, 97, 180–189.

Kostova, T., Beugelsdijk, S., Scott, W. R., Kunst, V. E., Chua, C. H., & van Essen, M. (2020). The construct of institutional distance through the lens of different institutional perspectives: Review, analysis, and recommendations. Journal of International Business Studies, 51, 467–497.

La Porta, R., López de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1113–1155.

Lerner, J., & Tag, J. (2013). Institutions and venture capital. Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(1), 153–182. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0007681310001783?via%3Dihub

Li, J., Ngin, P., & Teo, A. (2007). Culture and Leadership in Singapore: Combination of the East and the West. Culture and Leadership across the World: The GLOBE Book of In-Depth studies of 25 societies (pp. 947–968). Routledge.

Liesch, P. W., & Knight, G. A. (1999). Information internalization and hurdle rates in small and medium enterprise internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 383–394.

Madhavan, R., & Iriyama, A. (2009). Understanding global flows of venture capital: Human networks as the carrier wave of globalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 1241–1259.

Nordstrom, K. L., & Vahlne, J. E. (1994). Is the globe shrinking? Psychic distance and the establishment of Swedish subsidiaries during the last 100 years. International trade: Regional and global issues (pp. 41–56). St. Martin’s.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Norton.

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.

North, D. C. (2006). Understanding the process of economic change. Academic Foundation.

Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. The Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179.

Ong, A., & Nonini, D. (1997). Underground empires: The Cultural politics of Modern Chinese Nationalism. Routledge.

Peng, M. W. (2003). Institutional transitions and strategic choices. The Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 275–296.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Great Britain: Basil Blackwell & Mott Ltd.

Schwens, C., Eiche, J., & Kabst, R. (2011). The moderating impact of informal institutional distance and formal institutional risk on SME entry mode choice. Journal of Management Studies, 48(2), 330–351.

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. Sage Publications, Inc.

Scott, W. R. (2002). The Changing World of Chinese Enterprise: An Institutional Perspective. In AnneS. Tsui & C.-M. Lau (Eds.), The Management of Enterprises in the People’s Republic of China (pp. 59–78). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-1095-6_4.

Shenkar, O. (2001). Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 519–535.

Vahlne, J. E., & Johanson, J. (2017). From internationalization to evolution: The Uppsala model at 40 years. Journal of International Business Studies, 48, 1087–1102.

Vahlne, J. E., & Johanson, J. (2020). The Uppsala model: Networks and micro-foundations. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(1), 4–10.

Vouga Chueke, G., & Mendes Borini, F. (2014). Institutional distance and entry mode choice by Brazilian firms. Management Research: The Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 12(2), 152–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRJIAM-05-2012-0484.

Wang, L. (2007). Four essays on venture capital. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Hong Kong.

Wright, M., Pruthi, S., & Lockett, A. (2005). International venture capital research: From cross-country comparisons to crossing borders. International Journal of Management Reviews, 7(3), 135–165.

Wu, B., & Deng, P. (2020). Internationalization of SMEs from emerging markets: An institutional escape perspective. Journal of Business Research, 108, 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.037.

Wu, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (2020). Dynamic capabilities of emerging market multinational enterprises and the Uppsala model. Asian Business & Management, 1–25.

Xin, K. R., & Pearce, J. L. (1996). Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. The Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1641–1658.

Yan, H., Hu, X., & Liu, Y. (2020). The international market selection of Chinese SMEs: How institutional influence overrides psychic distance. International Business Review, 29, 101703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101703.

Young, M. N., Ahlstrom, D., Bruton, G. D., & Rubanik, Y. (2011). What do firms from transition economies want from their strategic alliance partners? Business Horizons, 54(2), 163–174. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0007681310001783?via%3Dihub

Zacharakis, A. L., McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2007). Venture capitalists’ decision policies across three countries: an institutional theory perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(5), 691–708. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jeffery-Mcmullen/publication/5223284_Venture_Capitalists%27_Decision_Policies_Across_Three_Countries_An_Institutional_Theory_Perspective/links/55bfc16108ae9289a09b613c/Venture-Capitalists-Decision-Policies-Across-Three-Countries-An-Institutional-Theory-Perspective.pdf

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 341–363.

Zhao, L., & Ha-Brookshire, J. (2018). Importance of Guanxi in Chinese apparel new venture success: A mixed-method approach. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8, 1–19.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Thomas Mattson and Dr. Siddarth Vedula were extremely helpful during the data-collection stage of this project. The University of Hawaii at Manoa provided funding that supported this research.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

A portion of the wording of the abstract of tihs paper was published in the Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings in 2016. Some working in this paper may be that same as that found in the following dissertation which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed publication: Hudson, P. L. 2015.

Competing interests

The authors have no other interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hudson, Jr., P.L., Richardson, J. Venture capital internationalization in China and the Uppsala model. Int Entrep Manag J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-024-00984-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-024-00984-4