Abstract

This study tracks the development of nascent entrepreneurs’ (NE) belief systems (mental models) from the time they were seriously planning entrepreneurship to having started their firms. It aims to reveal their typical entrepreneurship-related belief systems to understand the underlying logic of the contents and their change. Cognitive theory predicts belief systems which are first relatively simple and partly shared, but turn more complex and more divergent, thus facilitating the mental representation of their firms’ different environments. The study finds that the NEs share coherent and rather developed belief systems at the outset. They also become more complex after the transition from prospective to actual entrepreneurship, but unexpectedly more uniform, reflecting the NEs’ need to mentally control not only the external environment but also internal issues they share, such as fears and self-efficacy. This implies that entrepreneurs’ cognitive evolution involves developing the conventional “cold” mental grip of the external environment, but also understanding their affective, “hot” side. The development paths can vary, suggesting a corresponding theoretic model. Methodologically, cognitive/causal mapping and semi-structured interviewing provide an accessible approach to studying both aspects of entrepreneurial cognitions. Pragmatically, the findings suggest that small business support should pay more attention to prospective entrepreneurs’ qualms and beliefs, often hidden and biased.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study explores the belief systems (mental models) of a group of Finnish nascent entrepreneurs (NE) from the time when they were first contemplating entrepreneurship to when they had started their new micro firms (NMF). It seeks tentative answers to two broad questions: First, do lay persons share coherent entrepreneurship-related belief systems which can be understood in terms of what is known about human cognition and their situation as NEs? Second, do the NEs’ belief systems change following the transition from prospective to actual entrepreneurship, and if so, what explains this?

At the background is the research direction called management and organization cognition (MOC) (Kaplan, 2011), which emerged in the 1980s. MOC was characterised by two premises in particular. First, organisational actors like CEOs possess mental representations– called belief systems, cognitive maps, dominant logics, mental models, schemas, etc. (Walsh, 1995) – which guide their perceptions, plans, decision-making and responses to competitive conditions (Porac et al., 1989). Second, the representations should correspond – have requisite varietyFootnote 1 – with the firms’ competitive environments (Walsh, 1995). These ideas were espoused saliently by Weick (1979) and followers (e.g., Bartunek et al., 1983), arguing that managers should “complicate themselves” to match their environments. Since then, numerous MOC studies have examined especially corporate managers’ knowledge/beliefs, showing that their soundness or defects are major factors in firm performance (cf. Engelmann et al., 2020; Gary & Wood, 2011; McNamara et al., 2002).

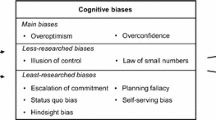

If studying corporate managers’ knowledge/beliefs is important, that should apply even more to entrepreneurs, yet this research is still rare. An explanation may be misconceptions about entrepreneurial cognitive research (ECR), instigated by proclamations that ECR’s “central question” is how entrepreneurs think (Mitchell et al., 2007). Recent reviews (cf. Mitchell et al., 2016, 2021) indicate that extant ECR has indeed essentially emulated cognitive psychology, migrated to entrepreneurial contexts, studying mental processes such as problem-solving styles (cf. Sarasvathy et al., 2015) or decision-making biases (cf. Abatecola et al., 2022), using clinical-experimental or verbal protocol methods (Baron & Ward, 2004; Sarasvathy et al., 1998, 2015).

Whilst cognitive process research is important, there are evident reasons for studying also the cognitive contents, i.e., what entrepreneurs know/believe, why so, and what consequences that has. First, the birth of new firms is influenced by potential entrepreneurs’ knowledge and beliefs. For instance, according to the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991), entrepreneurial intentions (EI) that precede individual entrepreneurship, result from attitudes toward entrepreneurship, observed social norms, and perceived behavioural control, which, in turn, depend on behavioural, normative, and control beliefs. However, although EIs are studied extensively currently (cf. Liñán & Fayolle, 2015; Donaldson, 2019; Nájera‑Sánchez et al., 2022), remarkably, the underlying beliefs, let alone of the formative or impact mechanisms, remain practically unresearched so far, although understanding better the “black box” behind EIs is theoretically and pragmatically important (Liñán & Fayolle, 2015). Second, the performance of new and small firms, too, depends significantly on the relevance and veridicality of the knowledge/beliefs of those who manage them (Frese, 2012; Hill & Levenhagen, 1995). Lastly, it is not unimportant that studying entrepreneurial knowledge/beliefs uses can use relatively accessible non-clinical methods like ethnography (Grégoire & Lambert, 2015; Johnstone, 2007) and cognitive/causal mapping (Laukkanen & Wang, 2015).

This study elicits, tracks and analyses the NEs’ mental models/belief systems using on-site semi-structured causal interviewing (SCI) and comparative causal (aka cognitive) mapping (CCM) (Laukkanen & Wang, 2015). In terms of design, this is a multiple case study (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Yin, 2015), each NE representing a case which, combined, underpin the conclusions. The NEs’ belief systems were elicited first when they were seriously contemplating entrepreneurship (T1), and 8–10 months later when they had started their firms (T2). The NEs’ entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions were measured at T1 as in typical TPB/EI studies. Their shared/typical belief systems are operationalised as aggregated cause maps (ACM) to provide tentative explanations of their initial state and development from T1 to T2.

The study hopes to contribute to entrepreneurship research, first, by revealing and helping understand the contents and formation of nascent entrepreneurs’ cognitive base. It aims at analytically, not statistically, generalisable conclusions (Maxwell & Chmiel, 2014; Yin, 2015) about how entrepreneurial belief systems develop at least in the context of “everyday entrepreneurship”, so far somewhat neglected compared with growth entrepreneurship (Kuckertz et al., 2023; Welter et al., 2016). Second, methodologically, the study demonstrates an accessible approach (SCI/CCM) to studying entrepreneurial knowledge. As recently argued (Hlady-Rispal et al., 2021), entrepreneurship research needs new qualitative strategies and methods to augment the still dominant nomothetic orientation. This study shows how this methodology can reveal the belief systems–the “black box”–argued to shape entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour.

The paper is structured as follows. It discusses next the study’s conceptual background and implications. The third section describes the empirical context, respondents, and methodology. The fourth presents the findings using numerical indicators, ACMs and analyses the NEs’ active concept bases. The fifth section summarises the results and discusses alternative explanations of the observed evolution of the NEs’ belief systems. Study’s limitations, further research needs and practical implications are addressed. The conclusions summarize the study.

Conceptual background

Mental representation

The idea that people construct internal models of their external worlds goes back to antiquity, but in explicit form it was proposed by the Scottish psychologist Craik first in 1943 (Johnson-Laird, 2005). Today, it is widely accepted that underpinning people’s purposive, reasoned behaviour are different knowledge structures (schemas) which represent their physical and social environments. In cognitive and social psychology the structures are called (causal) mental models (Markman & Gentner, 2001) or belief systems (Bandura, 2001; Connors & Halligan, 2015), sometimes cognitive maps (Axelrod, 1976; Kearney & Kaplan, 1997). We use the term belief system to refer to the aggregate of the respondents’ entrepreneurship-related expressed beliefs/knowledge and models.

Knowledge structures are constructed and run in the limited-capacity working memory (Baddeley, 2010), using conscious reasoning and imagination based on knowledge/beliefs and models that are recalled from long-term memory or generated de novo (Johnson-Laird, 2010; Markman & Gentner, 2001). The models provide “the causal network that we understand to be operating to make things happen” (Hoffman & Klein, 2017, p. 69). They contain knowledge/beliefs; propositions that people hold true or plausible about a domain or issue (Good & McDowell, 2015). Particularly relevant are phenomenological (that entities A, B, C, etc. exist) and causal beliefs (that A causes B, C follows from B, etc.). In practice, conscious reasoning means running the recalled and/or ad hoc constructed items and mental models in the working memory using “…kinematic simulation of the world” (Johnson-Laird, 2013, p. 132), thought experiments and if-then reasoning.

For psychologists, mental model notions conceptualise how people in general comprehend what exists, what happened and how things work (or might work) in some part of their world. This provides an intuitive account for human explanation, problem-solving and prediction; preconditions of reasoned action and mental security (Fiske & Taylor, 2021). In applied fields like MOC or entrepreneurship, the relevant corollary issue is how accurately the studied actors’ belief systems represent (are isomorphic with) their action environment (Frese, 2012; Hill & Levenhagen, 1995).

Origins of expressed beliefs

Over time, normal adults acquire a huge base of single items and more or less coherent systems of beliefs/knowledge (Chi & Ohlsson, 2005). Some result from personal experiences and inferences. Some, especially higher-level concepts and so-called tacit knowledge develop autonomously. However, the majority of what we know and believe has different social origins, transmitted by national and local cultures, primary and especially professional education, media, and by working and sharing knowledge in organisations. The processes and the resulting individual knowledge/beliefs differ widely. However, people also share some basic cognitive characteristics and important formative contexts and factors, which enables broadly anticipating what specific persons like the NEs may think and express when probed about a specific issue like entrepreneurship.

First, people’s social environments influence their beliefs. An important aspect is the national culture, mediated through prevailing values, beliefs, and reasoning patterns (Bender et al., 2017; Hayton et al., 2002). For instance, the Finnish culture shuns uncertainty and is highly individualisticFootnote 2 which should influence especially ideas about factors that foster or hinder entrepreneurship. In market economies, a further pervasive element is common experiences as employees and customers and the frequent media discussion of economic and business topics. Even lay persons will hear about notions like entrepreneurship, sales, profit, marketing, etc. Someone interested in entrepreneurship should be particularly receptive to such contents.

Second, belief formation involves some common patterns. Normal persons are driven by a need to understand and to avoid uncertainty by making sense of the problems, tasks and situations they face. This is supported by innate cognitive tendencies and abilities such as the assumption of causality, that things always have causes which can be known or conjectured (Kahneman, 2011), and the theory of mind, our ability to reason or speculate about what others think and thus explain their behaviours (Fiske & Taylor, 2021). There are also everyday heuristics (Westmeyer, 2001), some of which facilitate teleological or functional attribution of behaviours or events by projecting motives or functions. Some support tautological or environmental explanations by assuming unique faculties or compelling conditions. Such logics could underlie, e.g., beliefs why people become entrepreneurs or why they or their firms succeed or fail. Lastly, we are “cognitive economizers” (Fiske & Taylor, 2021), who seek information and think only as long as seems necessary for a momentarily adequate understanding of the situation. We also shun cognitive dissonance by maintaining a subjective consistency of our aims, beliefs, observations, decisions, and behaviours (Wyer & Albarracín, 2005).

Expectations

What beliefs might the NEs express about entrepreneurship when probed at T1 and T2? To begin with, they can be assumed to possess normal cognitive capabilities and tendencies and thus the mental tools and motivation to seek and maintain a personally satisfactory understanding. In the NEs’ case, this implies more or less developed notions about different aspects of entrepreneurship.

As to their beliefs at T1, the theoretical reasoning suggests that they have coherent but probably still general views about entrepreneurship. First, that they seek formal counselling indicates that entrepreneurship is a personally important issue, which has occupied their minds for some time. Second, the NEs represent a broadly similar cultural, economic and media environment. Third, as prospective entrepreneurs, they share cognitively a similar problem situation. Lastly, the NEs can be expected to emphasise the positive aspects of entrepreneurship but also show awareness of the risks. Combined, such factors should drive and influence but also align their needs of comprehension and information. Thus, the NEs’ T1 belief systems should be noticeably convergent. If so, a relatively detailed T1 aggregated cause map (ACM) will emerge to represent the NEs’ shared/typical thinking.

As regards the change of the NEs’ beliefs following the transition from prospective to actual entrepreneurship at T2, the theoretic discussion suggests that it should reflect the principle of cognitive isomorphism. Being a prospective entrepreneur and actually becoming one, imply two different situations and thus different cognitive demands. The NEs must adopt new notions and causal relationships which enable mentally representing the new external situation where they operate. Consequently, the individual belief systems should become more complex. A different matter is whether they become more divergent or more uniform. This should depend on the NEs’ businesses and the corresponding strategic and operative environments. If they differ, as in this case, the T2 belief systems should become more divergent. If so, the T2 ACM, which represents the NEs’ shared beliefs, would not differ much from the T1 ACM, it could be even simpler.

Revealing and representing belief systems

Mental models, belief systems, etc. are theoretical constructs. They cannot be observed directly, only inferred of a person’s or group’s expressed propositions that represent their knowledge/beliefs that the focal issue/domain comprises some entities (a, b, c, etc.), which have some causal relationships (a → b, b → c, etc.) (Sloman & Lagnado, 2015; Smith & DeCoster, 2000). Such proposition data must be usually elicited using normal natural language (Evans, 1998; Gentner, 2004; Ifenthaler et al., 2011). In rare cases, causal mapping can use prior documents (Axelrod, 1976).

This study elicits data by on-site semi-structured causal interviewing (SCI) and uses comparative cognitive/causal mapping (CCM) to represent and analyse the NEs’ shared belief systems (Carley & Palmquist, 1992; Laukkanen & Wang, 2015). Underpinning the approach is the theoretic notion that mental models/belief systems are basically networks of causal propositions (a → b, b → c, etc.). (Hoffman & Klein, 2017). Cause maps consist of nodes and arrows which correspond to actors’ phenomenological and causal beliefs, thus providing an intuitive representation of the belief systems. Causal mapping is commonly used to study especially group-level belief systems, e.g., in political science (Axelrod, 1976), mental model research (Ifenthaler et al., 2011), MOC (Engelmann et al., 2020; Schraven et al., 2015), and recently in entrepreneurship (cf., Correia Santos et al., 2010; Khelil, 2021; Laukkanen & Tornikoski, 2018; Tremml, 2020).

Technically, SCI elicits primarily causal propositions, not free-flowing discourse, simplifying data management and minimising errors. Computerised CCM facilitates efficient and transparent data processing and quantitative analysis of the belief systems. Importantly, causal mapping enables presenting and analysing the elicited belief systems visually. Here, the NE’s typical belief systems are represented as aggregated causal maps (ACM), which are generated by intersecting the individual cause maps (ICM). Overall, the CCM/SCI method facilitates a systematic elicitation, presentation and tracking of the NEs’ belief systems, all critical tasks presently. The downside is the need of uniform, preferably on-site data elicitation and learning and using the computerised processing, analysis and presentation methods.

Research context and methods

Study context and participants

The study’s respondents are nascent entrepreneur (NE) clients of Finnish Entrepreneurship Agencies (FEA), the leading provider of small business advisor (SBA) services. In a normal year, FEA serves 15 000 clients, helping found around 8 000 firms: corresponding to roughly one half of Finland’s early-stage entrepreneurs and a third of new firms. The SBAs assess the clients’ business ideas and qualifications and recommend whether and how to realise their projects. They also provide network and financing contacts and write recommendations for a state-sponsored start-up allowance.

Because FEA’s client list is confidential, random sampling of the respondents was not possible. The NEs’ participated voluntarily. To ensure that the first interviews mirror their initial thinking, only those NEs who had not begun the SBA process were selected. The interviews were conducted individually in FEAs’ offices in different cities.

The plan was to grow the sample by adding participants based on the saturation of the elicited concepts. The T1 group consisted of 13 NEs. There were 8 female and 5 male participants, mean age M = 44, 1 yr. (10,24). Six had a university, five a polytechnic and two a trade school degree, indicating a higher education level compared with typical Finnish micro entrepreneurs (Suomalainen et al., 2016).

The NEs were approached again for the T2 interviews. Three were not available anymore. The 10 NEs were interviewed 8–10 months after T1. Seven had started a business, three postponed or abandoned their projects. Because of the small number of non-founders, this study focuses on the founder NEs (N = 7). This group was found uniform and sufficient for the study’s theoretic purposes. There were 4 female and 3 male NEs. The mean age was M = 45, 1 yrs. (9,58). Four had a university, 2 a polytechnic and 1 a trade school degree, a somewhat higher level than the T1 average.

At T1, the NEs were inquired about their reasons for seeking FEA counselling. All founder NEs told they were planning to start a firm. Their businessesFootnote 3 were: (1) PR and communication services for local firms and communities, (2) program creation and production for mass media, (3) international consulting of government organisations, (4) personal training, (5) special consulting for metal industry, (6) photography studio, and (7) web-services for private and small business customers.

To assess the NE’s homogeneity as a group, their entrepreneurial intentions (EI) were inquired using a questionnaire of standard Likert-type statements (scale 1–5),Footnote 4 common in TPB based EI studies (Ajzen, 2002; Iakovleva et al., 2011; Kautonen et al., 2015). In addition, they were asked how certain (0–100%) they are about becoming entrepreneurs. The NE founders’ responses (see Table 1) indicate, on average, high homogeneity in entrepreneurial terms.

Methodology

The study’s methods, comparative cognitive causal mapping (CCM) and semi-structured causal interviewing (SCI) are summarised below. Detailed descriptions can be found in literature (Laukkanen & Wang, 2015).

The huge volume and diversity of people’s beliefs and mental representations mean that they can be only captured as far they concern some specific, to them relevant issues. The NEs’ beliefs were elicited and tracked focusing on two key phenomena: individual entrepreneurship and the emergence and performance of micro firms. In practice, they were interviewed around four anchor topics: (1) Why does one become an entrepreneur and what hinders or discourages that. (2) What results when an entrepreneur succeeds or fails. (3) What are the causes of micro firms’ success and failure. (4) What consequences have micro firms’ success or failure?

At the outset, it was emphasised that the key is to hear the NEs’ own views, that no sensitive issues are discussed, and that only aggregated findings will be reported. The interviewing began by asking what the respondent thinks causes individual entrepreneurship. This elicits a first batch of concepts. Next, the elicited concepts were used as new anchors, following the same format by inquiring about their causes. This elicits a second batch of original concepts and causal links. After the causes, things that prevent entrepreneurship were addressed. Next, the consequences of the first topic were inquired in a similar way. The other anchor topics were addressed correspondingly. To keep the duration realistic, this study only inquired about the causes of the first-batch causes and about the consequences of the first-batch effects. All elicited concepts were treated as equal.

The SCIs’ idea is to initiate and maintain a natural but focused discourse around the focal issues, observing reasonable uniformity of response times and additional probes. The T1 SCI’s mean duration was M = 66.77 min (SD = 13.99), at T2 somewhat longer (M = 116.00 min, SD = 10.32), a significant difference (U = 49.0, p = 0.001). Inquiring about the respondents’ demographics, backgrounds, plans and entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions took roughly an additional hour.

SCI data consists of a large number of original causal propositions (a → b, b → c, etc.), called natural causal units (NCU), that something influences or follows from something else. The NCUs and the concepts (a, b, c, etc.), called natural language units (NLU), were entered into CMAP3,Footnote 5 a CCM application to be standardized and processed, producing two databases, one for standard node terms (SNTs) and one for standard causal units (SCUs). CMAP3 also determines the ownership of each SNT and SCU, i.e., which NE had expressed correspondingly coded NLUs. This facilitates defining the SCUs of a specific number of NEs. They can be converted into aggregated causal maps (ACM in Figs. 1 and 2) to represent the NEs’ shared/core belief systems. Also CCM statistics and indicators such as the cause map densities and mutual distances (Table 1) are calculated.

Using natural language data requires its standardising (coding) (Laukkanen & Wang, 2015). This interprets and assigns the NLUs into appropriate standard node term (SNT) categories that represent the NLUs’ original referents and central meanings, observing synonyms and homonyms. Standardising translates the NLUs (in Finnish) into a standard meaning space and language (here English) and compacts data by removing (presently) redundant details like polar states or descriptive attributes, common in everyday discourse. Importantly, standardising facilitates comparing the respondents’ expressed notions and determining the similarity or difference of their expressed beliefs.

Standardising/coding is obviously critical. Notably, this study’s standardising was at low level, meaning that the standard term vocabulary (coding scheme) is close to natural language (Laukkanen & Wang, 2015). This accomplishes the necessary comparability, compacting and translation of the NLUs whilst observing the essential conceptual similarities and differences of the respondents. Exceptions are some functionally close NLUs which were combined under an abstract, “synthetic” standard term. For instance, E efficacy/self-esteem/drive comprises NLUs like trusting one’s business idea, feeling energetic, and differently expressions of self-confidence; E-defects/errors contains NLUs such as incompetence, laziness, greed, and so-called “personal” (alcohol) problems. F-change/development refers to the firms’ restructuring, renegotiation of terms, training, added businesses, etc. Technically, low-level coding simplifies interpreting and processing the NLUs. It also minimises errors and fosters the semantic validity of the resulting individual and aggregate cause maps. The study’s standardising was assessed by two external expert reviewers. There was a high percent agreement (IRR = 99.42%) with the original coding, suggesting high validity.

Validity

Assessing this study’s validity (credibility) involves two issues. First, do the data and ultimately the aggregated cause maps (ACM) represent the NEs’ genuine shared/typical beliefs? This depends first on the respondents’ sincerity (Axelrod, 1976): Did they say what they think and mean what they said? This can be only inferred. The NEs were interviewed about shared, personally relevant but non-sensitive topics following a standard protocol. They had no evident motive to systematically hide or fabricate their beliefs nor could they collude to align what they all will say. Thus, indirect evidence of validity is the relatively detailed ACMs that emerged when intersecting the NEs’ individual cause maps (ICM). This is not possible unless the underlying belief systems are widely shared.

Second, this study is not concerned with the statistical (population) generalisability of the NEs belief systems but with the analytic generalisability (Maxwell & Chmiel, 2014; Yin, 2015) of two conceptual notions implied by cognitive theory: (1) Have entrepreneurial actors like the NEs coherent belief systems that make sense considering their background and task situation. (2) Can the development of their belief systems be understood as an effort to achieve and maintain a cognitive grip, isomorphic with the changing external situation? Conceptual questions like these do not need large Ns; only a sufficient number of cases to conceptualise and establish the existence and relevance of the focal phenomenon (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). A comparable case is the verbal protocol study of Sarasvathy et al. (1998), which examined 4 bankers and 4 entrepreneurs. They were found to follow distinct problem-solving approaches, later conceptualised, respectively, as causation and effectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001).

The methodological precondition of this like the Sarasvathy et al. study is that the groups are internally homogeneous but differ in a key respect. Generally, it has been found (Guest et al., 2020) that even small samples, typically 6–7 respondents, are sufficient to determine what homogeneous groups typically think. Here, the NEs’ expressed intentions and business ideas at T1 (see Table 1) indicates that they constitute, in entrepreneurial terms, a homogeneous group, shown also by the early saturation of their concept base (Table 1). This suggests that using even considerably larger NE samples would not have elicited essentially different belief systems.

Findings

This section presents the NEs’ belief systems at T1 and at T2 using numerical indicators and aggregated cause maps (ACMs). The changes of the belief systems are analysed in terms of active SNTs. Theoretical conclusions and pragmatic implications are presented in the Discussion section.

Numerical summary

As shown in Table 1, T1 interviews elicited, on average, 67 NLUs and 94 NCUs per respondent; T2 interviews 141 NLUs and 207 NCUs. After standardising, the NEs had at T1 on average 39 SNTs (SD = 6.60) and 78 SCUs (SD = 13.95) per respondent; at T2 58 SNTs (SD = 7.00) and 157 SCUs (SD = 31.02).

Based on the theoretical discussion, it was anticipated that the NEs’ belief systems become more complex from T1 to T2. This also happened: Compared with T1, the NEs discern about one half more SNTs and about twice more SCUs at T2. The higher complexity is shown also by the individual cause maps’ (ICM) higher densities.Footnote 6

Second, the NEs’ belief systems were expected to become more divergent from T1 to T2. This can be examined using the C/D index (correspondence/distance). It measures how far their ICMs overlap by calculating (in percentages) the mutual sharedness of the NEs’ SNTs (Table 1). The T1 C/DI M = 0.54 (0.04) means that about half of all SNTs were shared, suggesting fairly shared belief systems. Unexpectedly, however, at T2 the C/DI was higher (M = 0.68, 0.03), indicating that nearly 70% of the SNTs were shared although the NEs’ average SNT bases grew from 39 to 58 (48.7%). This means that the NEs had adopted several new notions, many of which were shared, not different, as expected.

Concept base saturation

An important perspective to the NEs’ cognitive development is provided by the saturation of their active standard node terms (SNTs) (Guest et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2000). Their accumulation was tracked from the first respondent (S03) to the last (S13). As shown in Table 1, at T1 nearly all (91,4%) of the SNTs (n = 70) emerged by the 4th respondent (S10), the next NE contributing some SNTs, the rest none. However, at T2, a reasonable saturation point (90.7%) was reached already by the 2nd respondent (S07) in spite of a larger T2 SNT base (n = 85). This means that the NEs’ belief systems became more unified, not more divergent from T1 to T2, as expected.

The observed saturation also guides the generation of the aggregated cause maps to represent the NEs’ typical belief systems. Although technically possible, simply combining all ICMs would produce unintelligible ACMs. To be analytically useful, the ACMs must be readable and include typical elements but exclude idiosyncratic notions. This implies an intersection threshold, generation total frequency (GTF), which defines the minimum number of NEs who own an SCU and thus which SCUs CMAP3 includes in the ACM. Tests showedFootnote 7 that a low cut-off point (GTF = > 2) generates much too dense ACMs. A higher level (GTF = > 4) produces compact ACMs but risks excluding probably common notions. Thus, the ACMs (Figs. 1 and 2) were generated using GTF = > 3. Their nodes (SNTs) are widely shared (TF Md = 5). Although complex, the ACMs provide a readable yet representative view of the NEs’ typical thinking at T1 and T2.

Belief system at T1

The first ACM (Fig. 1) presents the NEs’ typical belief systems at a time (T1) when they had contacted the FEA, but not yet begun the actual counselling. It summarises their views about the direct and next-level causes and consequences based on the interviews. There are 35 nodes (SNT) and 57 causal relationships (SCU). Although self-explanatory when examined systematically, some general comments may be useful.

First, the ACM shows that, for the NEs, key reasons for becoming an entrepreneur are need of independence, better quality of life, and securing an income. The reciprocal relationships show that some notions are perceived as causes and desirable outcomes of entrepreneurship. The practical requirements of entrepreneurship include a business idea (BI) and existing business potential, understood that the firm’s offering attracts income-bringing customers to generate enough turnover, both conditions of entrepreneurial and small business (E/SB) success. Further conditions include a “right” entrepreneur who has the appropriate capabilities and energy, and cooperation partners. E/NMF success means to the NEs that the new micro firm is profitable and may grow.

As to what hinders entrepreneurship, one explanation for the NEs is that the some of the above-noted success conditions are missing. However, the principal factor they think discourages, even prevents becoming an entrepreneur is fears about one’s entrepreneurial capabilities and about the personal, social, and financial consequences of an E/NMF failure. As main causes of a failure, they find the entrepreneur him/herself and market/demand problems. As for failure’s consequences, it is noteworthy that at T1 all NEs think it means bankruptcy, leading to a personal, social, and financial catastrophe. They seem unaware that typical micro firms are terminated in a controlled way with minor losses, if any. This might explain the rather gloomy beliefs.

Belief system at T2

The NE founders’ beliefs were elicited again 8–10 months after T1. The resulting ACM (Fig. 2) is visibly more complex. It has 59 SNTs and 100 SCUs: An increase of 24 SNTs (68.8%) and 43 SCUs (57.0%). There are 26 new SNTs. Two SNTs (F-partners/cooperation, E-background/experiences) were not shared enough to be included any more. It is noteworthy that the SNT base grew from T1 to T2 only 21.5% (Table 1). The larger T2 ACM is explained by the widely shared new SNTs and that some at T1 less shared SNTs now pass the intersection threshold (Table 2).

The T2 ACM shows that the NEs’ overall thinking grew more complex. They discern more details about the factors and relationships that underpin E/NMF-success. Also, their notions about the consequences of E/NMF-success and especially of E/NMF-failure seem more realistic, perhaps more sanguine. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that most of the new notions are located in the T2 ACM’s upper left corner and concern factors that are related to or influence the entrepreneurs themselves or entrepreneurship in general.

Identifying the change

The ACMs provide a holistic systemic view of the NEs’ typical belief system and facilitate mentally simulating their reasoning. However, to understand the observed changes and to infer the underlying logic–if there is one– the ACMs’ standard node terms (SNTs) must be analyseds. For this purpose, Table 2’s upper section displays the 26 SNTs that emerged at T2 and appear only in the T2 ACM. The lower part has 5 SNTs which became more salient, practically shared by all NEs at T2. As noted, two T1 notions (F-partners/cooperation, E-background/experiences) did not meet the T2 GTF threshold.

To tentatively understand what might underlie the belief systems’ change, the SNTs are grouped into four categories, based on what they mainly refer to. The theoretical implications are discussed later. Thus, category A comprises 14 + 2 notions that concern the NEs themselves; their mental state, personal issues and sensed cognitive development. The substantial number of these SNTs suggests that, after starting their firms, the NEs are more conscious than before of the factors and issues which drive and foster (or impede) one’s performance as an independent entrepreneur. The former type of SNTs include E efficacy/self-esteem/drive, E pull factors/motivation and E trade competence; E encouragement and E models/e-ship/growth referring to the social support they experience. Factors that cause difficulties or endanger success include E-characteristics/traits and E-defects/errors.

Category B contains 4 SNTs about pragmatic factors such as NMF financial/oper.control and NMF-oper.conditions/modes of which the NEs seem now more aware. Category C (4 + 2) refers to the positive and negative outcomes of entrepreneurship. The new, at T2 fully shared SNT E/family security may indicate an increased risk awareness resulting from becoming dependent on one’s performance as an entrepreneur. The new SNT E employer risks/tasks suggests that an employer status appears now possible, not hypothetical any more. This may apply also to E wealth/affluence and E financial difficulties which are more shared at T2, suggesting that the positive but also negative potential aspects of entrepreneurship have become more concrete to the NEs now.

Category D (4 + 1) refers to the external factors which an NE can mainly only observe and adapt to, perhaps excluding E/NMF reputation/image. Overall, the number of distinctly external notions appears surprisingly low. Interestingly, at T2, all NEs note Serendipity/calamity. This may indicate growing awareness of some things being beyond one’s control. The at T2 widely shared SNT E/NMF support/subsidies probably reflects the NEs’ eligibility to receive an Entrepreneur Allowance.

Discussion

General observations

The findings suggest, first, that the NEs have coherent and unspecific, yet broadly accurate notions about entrepreneurship and micro business at T1. This was also expected in view of their probably shared formative factors, in particular their personal situation and aspirations as prospective entrepreneurs, inherent and culturally transmitted reasoning patterns, and the common knowledge which normal adults should accumulate in a market economy. The NEs’ stereotypic notions about failure and their still vague business and accounting terminology indicate certain “cognitive economising”, not yet bothering about acquiring extensive knowledge of business practices and jargon. On the other hand, it was unexpected that fears concerning one’s entrepreneurial capabilities and the prospect of a failure would be so widespread and salient, nor that, for lay persons, the NEs’ typical thinking at T1 would be so uniform and detailed, manifested in the relatively complex ACM.

Second, the NEs’ belief systems were expected to change from T1 to T2 because starting a firm calls for problem-solving and information search processes to understand the new environment and master the ensuing tasks. Developing the necessary cognitive grip implies discerning and adopting corresponding new notions and influence mechanisms, which should be manifested in more complex individual cause maps (ICMs). This also happened. The number of NEs’ active concepts (SNT) grew by half, that of causal relationships (SCU) doubled. Moreover, the NEs’ thinking seems to have become more realistic and sophisticated, some of the new and now more salient concepts suggesting more abstract and nuanced thinking. For example, the NEs seem more aware of serendipity and that firms can be terminated also in controlled ways. They also perceive a wider set of positive and negative consequences of success and failure.

The NEs’ cognitive development was also expected to lead to more heterogenous individual belief systems, resulting from their firms’ different businesses and external environments, following the principle of isomorphism or requisite variety. However, this did not happen. The NEs’ typical belief systems at T2 became more uniform, not more divergent, although their complexity had increased markedly, as noted. This means that several of the new issues and concepts that entered their minds from T1 to T2 must be shared.

Understanding the evolution

What explains the belief systems’ increased convergence and the specific new contents? Three explanations come to mind. First, the problems which the NEs encountered are simpler or fewer than assumed so that there was correspondingly less need for different new notions. Second, some issues that were not widely shared at T1 became more shared by T2, having a unifying effect leading to the larger T2 ACM. Third, the NEs became conscious of shared problems or a task environment that were not expected on theoretical grounds.

The first explanation is supported by the observation that there are surprisingly few new notions about business, running a firm, and different aspects of the external environments (Categories B and D in Table 2). This can reflect a broad similarity of these NEs’ micro firms as relatively simple businesses, offering special services to single firms or private customers. At least at the outset, founding and managing such businesses does not need deep strategic thinking but mainly ensuring mundane conditions like NMF-financial /op.control or E trade competence, which all NEs do share. Noteworthily, their financial and accounting terminology still appears undeveloped at T2, possibly reflecting common NE practices of outsourcing office operations and financial control to accounting agencies.

As for the second explanation, there were indeed five T1 issues that became salient and widely shared by T2 (Table 2). It is noteworthy that they all concern, in one way or other, the entrepreneurs themselves. This also includes E culture/values/attitudes, suggesting deeper appreciation of a (ideally supportive) social atmosphere. Importantly, as noted, none of the new shared notions refer to the external business environment.

The third and theoretically more interesting explanation is that the NEs met a shared task environment which was not expected a priori. This is supported by the high number of entirely new and at T2 more salient shared concepts (Table 2, Category A) which refer to the NEs themselves, but which cannot be considered essential to everyday operating of a micro business. That they appeared at all and so consistently suggests that the development of the NEs’ belief systems cannot be explained entirely in terms of rational efforts to mentally grasp the external environment in order to run a micro firm there. A tentative hypothesis is suggested by the at T2 more salient role of NEs’ fears about their capabilities and the consequences of a failure, perceived dismal at T1. Assuming this, it seems natural and predictable that lay persons like the NEs, who have a wage job background and who become independent regardless of their fears, will experience emotional anxiety and uncertainty, and that overcoming those fears and mentally controlling their entire situation, becomes paramount in the initial stages after launching the firm. Furthermore, considering the common tendency to shun cognitive dissonance, normal persons can be expected to tend to believe and to see supporting evidence that one can do what is necessary and that the environment cooperates so that critical conditions like customers exist, all making the new situation appear manageable and acceptable. The T2 ACM shows cognitive traces of such thinking. Especially fully shared new SNTs like E-efficacy/self-esteem/drive, E-trade competence and E-confidence/courage can be interpreted thus.

The observations suggests that the development of the NEs’ belief systems should be understood to result from both rational-cognitive and affective or emotional factors. In other words, underpinning the development are ongoing cognitive processes which aim, first, at conceptualising and cognitively adapting to and controlling the perceived external environment, and second, mastering oneself by coming to grips emotionally with the apprehensions and uncertainties that were instigated by the transition to independent entrepreneurship.

Theoretical implications

The study supports the general notion that entrepreneurial actors such as nascent entrepreneurs develop coherent belief systems which make sense in view of current knowledge about human cognition and of the actors’ backgrounds and changing situations. More importantly, the study finds that the cognitive development can involve both rational and affective processes, driven by the actors’ need to conceptualize and comprehend the external context, and their simultaneous need to achieve a mental and emotional balance by coping with their fears and uncertainties. It follows that the target to “map” or represent cognitively is not only something literally external like the firm’s competitive environment, as previously assumed. For individuals facing a personally demanding situation, also their emotional states can be integral, even critical segments of the total situation. Consequently, they need knowledge and understanding which facilitate a subjectively adequate cognitive mastering of their business and themselves.

However, it is clear that the NEs represent a specific, albeit probably common case of entrepreneurial cognitive development. More generally, it can be conceptualised to involve two interwoven processes. One “actualises” the entrepreneurs’ knowledge and understanding of their specific strategic and operative external situation; the other their emotional states, motivation and especially self-efficacy (Ajzen, 2002; Bandura, 1994). The processes can be presented as a tentative model (Fig. 3), where the quadrants represent four basic mindset categories.

According to the model, the cognitive development of entrepreneurs can involve quite different mental drivers, starting points, developments and end-states. The reasoning suggests some entrepreneur prototypes and hypothetical development paths. For instance, there can be “reluctant necessity self-employers” who must become independent, but have no true motivation and little idea of what it takes; “serial entrepreneurs” effectively copy-pasting their business once more into a new location; and “start-up professionals” who face organisational restructuring and buy the business unit they have been managing with an intention of owning and running it as a new independent firm. As for the study’s NEs, on average, they probably started somewhere in Q1 at T1 and were entering Q4 at T2.

The study suggests a new perspective and contributes at least to two current discussions in entrepreneurship. The first concerns “cold v. hot” cognition (Cardon et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2021; Welpe et al., 2012). Cold cognition refers to actors’ deliberate calculation and understanding of external situations such as the operative and strategic contexts in MOC studies following the requisite variety hypothesis. In contrast, hot cognition reflects the affect-as-information view that “…we are informed by our affect, even though we produce it ourselves” (Clore & Bar-Anan, 2007, p. 15). In practice, e.g., proposed plans can cause intuitive uneasiness which prudent decision-makers observe. In the NEs’ case, the emotional driver was probably the entire situation characterised by the transition from potential to actual entrepreneurship.

Second, the study illuminates the so far largely unresearched belief systems posited to underpin entrepreneurial intentions (EI) by the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), discussed at the outset. In particular, the findings support the TPB notion of affective factors’ role in entrepreneurship, increasingly emphasised in literature (cf. Cardon et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021). For example, the TPB factor perceived control of behaviour (PCB) is largely an affective issue of self-efficacy (Ajzen, 2002; Bandura, 1994), although in entrepreneurship, PCB must comprise also concrete conditions like securing resources and customers. The study’s aggregate cause maps (Figs. 1 and 2) provide a broad view of the studied respondents’ belief systems which lie behind their PCB but also behind the other EI factors.

Methodological implications

The study shows that the combination of on-site semi-structured causal interviewing and comparative causal mapping (SCI/CCM) can reveal and track the development of entrepreneurial actors’ causal knowledge/beliefs. Technically uncomplicated, it facilitates different cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of the contents, formation and impact of entrepreneurial cognitions such as the beliefs that TPB posits underpin entrepreneurial intentions.

A less evident but arguably important conclusion is that the SCI/CCM approach facilitates exploring also entrepreneurial emotions in a way that comes close to ideal of longitudinal case data and non survey-based methods (Cardon et al., 2012, p. 5). That cognitive mapping can explore also affective issues has apparently not been commonly realized, perhaps because of the traditional focus on mainly social or socio-technical domains (cf., Engelmann et al., 2020; Ifenthaler et al., 2011; for an exception, cf. Schulte-Holthaus & Kuckertz, 2020). Accordingly, e.g., Hodgkinson and Healey (2011, p. 1512) have suggested “modifying” cognitive mapping techniques to “…elicit and represent feelings and affective reactions”. This study suggests, however, that this is unnecessary nor is there some unknown magic way. First, as noted, cognitive mapping data consists necessarily of causal assertions, communicated in some form. Second, if an emotion is not incapacitating, “… it leads the person experiencing it to reason about its cause.” (Johnson-Laird (2013, p. 134), triggering corresponding memory recall and reasoning processes. Therefore, people can, in principle, talk about affective issues like fears, being independent, pride, etc. They also often want to talk but only if there is trust and an appreciative listener. However, persons and cultures (Welter & Alex, 2012) differ in terms of ability and readiness to discuss emotions.

Limitations and further research

The study’s main limitation is that it could track the cognitive development of only one category of entrepreneurs. Therefore, further research is needed to understand better how different entrepreneurs’ belief systems evolve. An obvious direction would be to extend tracking the NEs. For instance, it would seem that if things go well, entrepreneurship becomes a routine affair whereby the earlier affect-dominated cognitions may be replaced by wealth-oriented and operative and even strategic notions. In a crisis, however, affects such as fears can re-emerge. Another direction would compare or track the progression of the belief systems of different entrepreneur categories. These include the above-noted prototypes (Fig. 3), clients of advisory organisations, franchisees of large firms, and university-based start-up groups. In all such studies, the present SCI/CCM approach can be applied.

Implications for practice

The study has implications especially for small business advisors (SBA). First, it shows that affective issues can be important especially for nascent lay entrepreneurs. However, emotional aspects seem largely disregarded in entrepreneurship development literature (cf. Atherton, 2006; Bennett & Robson, 2005). Moreover, SBA practices seem to emphasise NEs’ business ideas and financial calculations, not their fears or qualms (Laukkanen & Liñán, 2022); understandable considering typical SBAs’ business background, limited counselling time, and common stereotypic notions about “appropriate” entrepreneurial behaviour.

However, it can be argued that SBA should help NEs address, understand, accept and manage normal emotions like fears (Cacciotti et al., 2016), especially be more openly addressing the possibility of a failure and its management. This can prevent giving up unthinkingly, but also foster diligence and curb overconfidence. Perhaps less obvious is that that tackling such issues offers SBAs opportunities to teach “optimistic paranoia”, a key characteristic of successful managers and entrepreneurs (Grove, 1999; Siilasmaa, 2019). Moreover, knowing that NEs can handle eventual difficulties, the usually highly risk-aversive SBAs may recommend more aggressive and impactful projects.

Furthermore, SBA organisations could pay explicit attention to the entrepreneurship and business beliefs and their clients’ cognitive blind spots. In practice, this calls for open discussions, why-questions and listening, not lecturing. For more systematic assessment of the scope and accuracy of NEs’ thinking before and after counselling, simplified CCM methods and standard questionnaires could be used.

Conclusion

This study has shown, first, that entrepreneurial actors such as nascent entrepreneurs (NE) have coherent belief systems (aka cognitive maps, mental models) about entrepreneurship and micro business systems so as to enable mentally representing and comprehend what exists in their environment and how things work there. Whilst long common in applied fields like MOC, the notion of mental representations guiding reasoned behaviour, and the corollary idea of actually adopting and using this perspective theoretically and empirically has not yet really permeated entrepreneurship.

Second, the findings suggest that the development of entrepreneurs’ belief systems can be explained and logically understood. In the NEs’ case, it was driven by their need to mentally represent the external environment, as conventionally assumed, but even more by having a cognitive grip of their internal affective state, accentuated by the fears and uncertainties related to the transition from prospective to actual entrepreneurship. However, it is evident that these processes vary depending on the entrepreneurs’ background, experience, initial and actual situation, etc. The findings suggest a general model of entrepreneurial belief formation and directions for future research.

Third, the study demonstrates a technically accessible methodology, comparative cognitive/causal mapping (CCM) and on-site semi-structured causal interviewing (SCI), for disclosing and analysing entrepreneurial actors’ belief systems. It also facilitates tracking and thus a longitudinal view of the respondents’ thinking and its development. The aggregated cause maps, which represent shared belief systems, help simulate the respondents’ reasoning, augmented by heuristically useful quantitative analysis. A new, indirect conclusion was that SCI/CCM enables exploring also entrepreneurs’ affective side.

Lastly, the findings have implications for entrepreneurship development. The study suggests that especially lay nascent entrepreneurs may have erroneous initial beliefs about entrepreneurship and business, and that the prospect and the actual realisation of entrepreneurship can trigger critical emotional issues. Both the beliefs and the affective aspects deserve arguably more attention than seems customary now, in practice, small business advisors openly tackling issues like fears and failure and by systematically disclosing and tracking their clients’ key beliefs.

Notes

The theorem or “law” of requisite variety (Ashby, 1956) states that regulators must be isomorphic with the system being regulated, the corollary being that “…the living brain, so far as it is to be successful and efficient as a regulator for survival, must proceed, in learning, by the formation of a model (or models) of its environment.” (Conant & Ashby, 1970, p. 87).

For recent data: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/ (accessed March, 2023).

To preserve anonymity, the respondents’ gender is not noted and the order of their firms/businesses in the text differs from the interview order in Table 1.

TPB/EI questionnaire scale: 1 = fully disagree, 2 = rather disagree, 3 = not disagree nor agree, 4 = rather agree, 5 = fully agree.

CMAP3 can be downloaded at: https://www3.uef.fi/fi/web/cmap3, IHCM CmapTools at: https://cmap.ihmc.us/cmaptools/. It generates graphic maps using SCU sets that CMAP3 exports as clx-files. Both software are free (accessed March, 2023).

CMAP3 calculates ICM density by comparing the number of SCUs with their theoretic maximum number assuming only unidirectional relationships.

Using GTF = > 2 the T2 ACM would have 74 SNTs and 225 SCUs; using GTF = > 4 there would be 37 SNTs and 56 SCUs. The ACM (GTF = > 3) in Fig. 2 has 59 SNTs and 100 SCUs.

References

Abatecola, G., Cristofaro, M., Giannetti, F., & Kask, J. (2022). How can biases affect entrepreneurial decision making? Toward a behavioral approach to unicorns. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 18, 693–711.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal ofApplied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683.

Ashby, W. R. (1956). An introduction to cybernetics. Chapman & Hall.

Atherton, A. (2006). Should government be stimulating start-ups? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 24, 21–36.

Axelrod, R. (Ed.). (1976). Structure of decision: the cognitive maps of political elites. Princeton University Press.

Baddeley, A. (2010). Working memory. Current Biology, 20(4), 136–140.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). New York: Academic Press.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26.

Baron, R. A., & Ward, T. B. (2004). Expanding entrepreneurial cognition’s toolbox: potential contributions from the field of cognitive science. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 28, 553–573.

Bartunek, J. M., Gordon, J. R., & Weathersby, R. P. (1983). Developing “complicated” understanding in administrators. Academy of Management Review, 8, 273–284.

Bender, A., Beller, S., & Medin, D. L. (2017). Causal cognition and culture. In M. R. Waldmann (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of causal reasoning (pp. 717–738). Oxford University Press.

Bennett, R. J., & Robson, P. J. A. (2005). The advisor-SME client relationship: impact, satisfaction and commitment. Small Business Economics, 25, 255–271.

Cacciotti, G., Hayton, J. C., Mitchell, J. R., & Giazitzoglu, A. (2016). A reconceptualization of fear of failure in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(3), 302–325.

Cardon, M. S., Shepherd, D. A., & Baron, R. (2021). The Psychology of entrepreneurship: looking 10 years back and 10 years ahead. In M. M. Gielnik, M. S. Cardon, & M. Frese (Eds.), The psychology of entrepreneurship: new perspectives (pp. 377–394). Routledge.

Cardon, M. S., Foo, M. -D., Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36, 1–10.

Carley, K., & Palmquist, M. (1992). Extracting, representing, and analyzing mental models. Social Forces, 70(3), 601–636.

Chi, M. T. H., & Ohlsson, S. (2005). Complex declarative learning. In K. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 371–399). Cambridge University Press.

Clore, G. L., & Bar-Anan, Y. (2007). Affect-as-information. In R. Baumeister & K. Vohs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of social psychology (pp. 13–15). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Conant, R. C., & Ashby, W. R. (1970). Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system. International Journal of Systems Science, 1(2), 89–97.

Connors, M. H., & Halligan, P. W. (2015). A cognitive account of belief: a tentative road map. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(1588), 1–14.

Correia Santos, S., Curral, L., & Caetano, A. (2010). Cognitive maps in early entrepreneurship stages: From motivation to implementation. Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 11(1), 29–44.

Donaldson, C. (2019). Intentions resurrected: a systematic review of entrepreneurial intention research from 2014 to 2018 and future research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(3), 953–975.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32.

Engelmann, A., Kump, B., & Schweiger, C. (2020). Clarifying the dominant logic construct by disentangling and reassembling its dimensions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 22, 323–355.

Evans, J. S. B. T. (1998). The knowledge elicitation problem: a psychological perspective. Behaviour and Information Technology, 7(2), 111–130.

Fiske, S., & Taylor, S. E. (2021). Social cognition: from brains to culture (2nd ed.). Bodmin: SAGE.

Frese, M. (2012). The psychological actions and entrepreneurial success: an action theory approach. In J. R. Baum, M. Frese, & R. A. Baron (Eds.), The psychology of entrepreneurship. Taylor and Francis, Psychology Press, Kindle version.

Gary, M. S., & Wood, R. E. (2011). Mental models, decision rules, and performance heterogeneity. Strategic Management Journal, 32, 569–594.

Gentner, D. (2004). The psychology of mental models. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Bates (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 9683–9687). Elsevier.

Good, B., & McDowell, A. (2015). Anthropology of belief. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 493–497). Elsevier.

Grégoire, D. A., & Lambert, L. S. (2015). Getting inside entrepreneurs’ hearts and minds: methods for advancing entrepreneurship research on affect and cognition. In T. Baker & F. Welter (Eds.), The Routledge companion to entrepreneurship (pp. 450–465). Taylor and Francis.

Grove, A. S. (1999). Only the paranoid survive: how to exploit the crisis points that challenge every company. Currency/Doubleday.

Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076,1-17

Hayton, J. C., George, G., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). National culture and entrepreneurship: a review of behavioral research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26, 33–52.

Hill, R. C., & Levenhagen, M. (1995). Metaphors and mental models: sensemaking and sensegiving in innovative and entrepreneurial activities. Journal of Management, 21(6), 1057–1074.

Hlady-Rispal, M., Fayolle, A., & Gartner, W. B. (2021). In search of creative qualitative methods to capture current entrepreneurship research challenges. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(5), 887–912.

Hodgkinson, G. P., & Healey, M. P. (2011). Psychological foundations of dynamic capabilities: reflexion and reflection in strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 32, 1500–1516.

Hoffman, R. R., & Klein, G. (2017). Explaining explanation, part 1: theoretical foundations. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 2017, 68–73.

Huang, Y., Foo, M. -D., Murnieks, C. Y., & Uy, M. A. (2021). Mapping the heart: trends and future directions for affect research in entrepreneurship. In M. M. Gielnik, M. S. Cardon, & M. Frese (Eds.), The psychology of entrepreneurship: new perspectives (pp. 26–47). Routledge.

Iakovleva, T., Kolvereid, L., & Stephan, U. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions in developing and developed countries. Education + Training, 53(5), 353–370.

Ifenthaler, D., Masduki, I., & Seel, N. M. (2011). The mystery of cognitive structure and how we can detect it: tracking the development of cognitive structures over time. Instructional Science, 39, 41–61.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (2005). Mental models and thought. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 185–208). Cambridge University Press.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (2010). Mental models and human reasoning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(43), 18243–18250.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (2013). Mental models and cognitive change. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(2), 131–138.

Johnstone, B. A. (2007). Ethnographic methods in entrepreneurship research. In H. Neergaard & J. P. Ulhøi (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research methods in entrepreneurship (pp. 79–121). Bodmin: Elgar.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle ed.

Kaplan, S. (2011). Research in cognition and strategy: reflections on two decades of progress and look to the future. Journal of Management Studies, 48(3), 665–695.

Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39, 655–674.

Kearney, A. R., & Kaplan, S. (1997). Toward a methodology for the measurement of knowledge structures of ordinary people. Environment and Behavior, 29(5), 579–617.

Khelil, N. (2021). Causal cognitive mapping in the entrepreneurial cognition field: a comparison of two alternative methods. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(5), 1012–1049.

Kuckertz, A., Scheu, M., & Davidsson, P. (2023). Chasing mythical creatures – a (not-so-sympathetic) critique of entrepreneurship’s obsession with unicorn startups. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 19, e00365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2022.e00365

Laukkanen, M., & Liñán, F. (2022). Uncovering entrepreneurial belief systems through cognitive causal mapping. In A. Caputo, et al. (Ed.), The international dimension of entrepreneurial decision-making (pp. 37–63). Springer.

Laukkanen, M., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2018). Causal mapping small business advisors’ belief systems: a case of entrepreneurship policy research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 24(2), 499–520.

Laukkanen, M., & Wang, M. (2015). Comparative causal mapping: the CMAP3 method. Gower Publishing.

Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907–933.

Markman, A. B., & Gentner, D. (2001). Thinking. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 223–247.

Maxwell, J. A., & Chmiel, M. (2014). Generalization in and from qualitative analysis. In U. Flick (Ed.), SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 540–553). Dorchester: SAGE.

McNamara, G., Luce, R. A., & Thompson, G. H. (2002). Examining the effect of complexity in strategic group knowledge structures on firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 153–170.

Mitchell, J. R., Mitchell, R. K., & Randolph-Seng, B. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of entrepreneurial cognition. Edward Elgar.

Mitchell, J. R., Israelsen, T., & Mitchell, R. K. (2021). Entrepreneurial cognition research–an update. In M. M. Gielnik, M. S. Cardon, & M. Frese (Eds.), The psychology of entrepreneurship: new perspectives (pp. 5–25). Routledge.

Mitchell, R. K., Busenitz, L., Bird, B., Gaglio, C. M., McMullen, J. S., Morse, E. A., & Brock Smith, J. (2007). The central question in entrepreneurial cognition research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(1), 1–27.

Nájera-Sánchez, J. -J., Pérez-Pérez, C., & González-Torres, T. (2022). Exploring the knowledge structure of entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-022-00814-5

Nelson, K. M., Nadkarni, S., Narayanan, V. K., & Ghods, M. (2000). Understanding software operations support expertise: a revealed causal mapping approach. MIS Quarterly, 24(3), 475–507.

Porac, J. F., Thomas, H., & Baden-Fuller, C. (1989). Competitive groups as cognitive communities: the case of Scottish Knitwear manufacturers. Journal of Management Studies, 26, 397–416.

Sarasvathy, S. (2001). Causation and effectuation: toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263.

Sarasvathy, S., Simon, H. A., & Lave, L. (1998). Perceiving and managing business risks: differences between entrepreneurs and bankers. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 33(2), 207–225.

Sarasvathy, S., Ramesh, A., & Forster, W. (2015). The ordinary entrepreneur. In T. Baker & F. Welter (Eds.), The Routledge companion to entrepreneurship (pp. 227–243). Taylor and Francis.

Schraven, D. F. J., Hartmann, A., & Dewulf, G. P. M. R. (2015). Resuming an unfinished tale: applying causal maps to analyze the dominant logics within an organization. Organizational Research Methods, 18(2), 326–349.

Schulte-Holthaus, S., & Kuckertz, A. (2020). Passion, performance and concordance in rock “n” roll entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(3), 1335–1355.

Siilasmaa, R. (2019). Transforming NOKIA: the power of paranoid optimism to lead through colossal change. McGraw-Hill.

Sloman, S. A., & Lagnado, D. (2015). Causality in thought. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 223–247.

Smith, E. R., & DeCoster, J. (2000). Dual-process models in social and cognitive psychology: conceptual integration and links to underlying memory systems. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 108–131.

Suomalainen, S., Stenholm, P., Kovalainen, A., Heinonen, J., & Pukkinen, T. (2016). Global entrepreneurship monitor finnish 2015 report. Turku School of Economics, University of Turku. Series A Research Reports, A 1/2016.

Tremml, T. (2020). Barriers to entrepreneurship in public enterprises: boards contributing to inertia. Public Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1775279

Walsh, J. (1995). Managerial and organizational cognition: notes from a trip down memory lane. Organization Science, 6, 280–321.

Weick, K. E. (1979). The social psychology of organizing (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Welpe, I. M., Spörrle, M., Grichnik, D., Michl, T., & Audretsch, D. B. (2012). Emotions and opportunities: the interplay of opportunity evaluation, fear, joy, and anger as antecedent of entrepreneurial exploitation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36, 69–96.

Welter, F., Baker, T., Audretsch, D. B., & Gartner, W. B. (2016). Everyday entrepreneurship–a call for entrepreneurship research to embrace entrepreneurial diversity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41, 311–321.

Welter, F., & Alex, N. (2012). Researching trust in different cultures. In F. Lyon, G. Möllering, & M. N. K. Saunders (Eds.), Handbook of research methods on trust (pp. 50–60). Elgar.

Westmeyer, H. (2001). Explanation: conceptions in social sciences. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Bates (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 5154–5159). Elsevier.

Wyer, R. S., & Albarracín, D. (2005). Belief formation, organization, and change: cognitive and motivational influences. In D. Albarracin, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 273–322). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Yin, R. K. (2015). Case studies. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 194–201). Elsevier.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (UEF) including Kuopio University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Laukkanen, M. Understanding the contents and development of nascent entrepreneurs’ belief systems. Int Entrep Manag J 19, 1289–1312 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00862-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00862-5