Abstract

The presented article focuses on examining two important areas within the framework of tourism development in the region, namely development management and cooperation of the interest groups in the tourism industry in the region. The main goal of the presented article is threefold: (1) identifying and measuring the perceived rate of problems in development management in the tourism industry, (2) identifying and measuring the perceived rate of problems of cooperation between the interest groups in the tourism industry, (3) examining connections between problem rates of development management and cooperation between interest groups in tourism. Based on professional literature, key factors (problems) in these areas were identified. Subsequently, tools to measure the rate of development, the reliability of which was verified based on McDonald's omega, were created. The article is supported by a primary survey in which 95 experts on the topic of regional tourism from Europe participated. The results indicate an average to above-average perceived rate of problems within the examined areas. An examination of the relationships between the problems of development management and the cooperation of interest groups in the development of regional tourism can be considered significant, where significant positive connections were confirmed. The results add to the knowledge base of the issue in question. At the same time, it is possible to identify practical benefits within the framework of identification, quantification and comparison of individual problems within the framework of tourism development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The management of tourism development in the region, its organizational structure as well as its tasks differ significantly (Calero & Turner, 2020) in different countries. However, most authors consider destination management organizations as strategic leaders of tourism development in the field of destination management. They agree on the need for effective destination management and relationship management in order to achieve a competitive advantage in the destination and link the success of the DMO (Destination Management Organization) to the competitiveness and success of the destination (Bornhorst et al, 2010; Mira et al., 2016 and many others), highlight their leadership position as a coordinator of diverse stakeholder relations in the field of destination and their cooperation (UNWTO, 2007; Wang & Fesenmaier, 2007; Kozak & Baloglu, 2011; Meriläinen & Lemmetyinen, 2011; OECD, 2012; Ness et al., 2014; Beritelli et al., 2015; Hristov & Ramkinssoon, 2016; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2016). Changes in the perception of cooperation in the destination are related to various transformations in the economic and social environment and, in particular, to a change in the perception of destinations as "entities comprising multiple products offering diverse tourist experiences" (Buhalis, 2000). The importance of cooperation is emphasized especially in times of crisis. This was pointed out in the last century by Wilson (1995), who said that it is easier to encourage subjects to cooperate during a crisis than during a boom period and a crisis is cited as one of the reasons for joining forces in a destination. The new study of Elvekrok et al. (2022) confirms that companies value cooperation in a destination if it contributes to their greater resilience to market fluctuation. Laesser, Ch., Stettler, J., Beritelli, P., & Bieger (AIEST, 2021) consider the extensive understanding of cooperation in the sense of horizontal, vertical and lateral cooperation as one of the challenges for the development of tourism even in the current crisis period caused by SARS-CoV.

Tourism development in the region has many aspects and faces various problems. The presented article deals with two of them, namely development management and regional cooperation. It is possible to identify key problems based on literature as well as various analytical studies and to create a tool for examining these problems and measuring their intensity, even if countries or individual regions perceive different problems in these areas. The main goal of the presented article is threefold: (1) identifying and measuring the perceived rate of problems in development management in the tourism industry, (2) identifying and measuring the perceived rate of problems of cooperation between the interest groups in the tourism industry, and (3) examining connections between problem rates of development management and cooperation between interest groups in tourism.

Literature review

Interest groups that should cooperate in the destination are often identified differently (Sheehan & Ritchie, 2005; Friedman & Miles, 2006; Bieger, 2008; UNWTO, 2019; Kvasnová et al., 2019). Beritelli et al. (2015) draw attention to the difficulty of reaching a consensus with the simultaneous involvement of all stakeholders with conflicting interests in the strategic process. However, Fayall and Garrod (2005) draw attention to the risk of non-involvement of important subjects in connection with reducing the effects of cooperation. Last but not least, they are the entities that have the power and resources to block or implement solutions and strategies (Lee et al., 2008). Pechlaner et al. (2012b) emphasize the need for the implementation of entities from all sectors of the economy, not only tourism. In both Wöhler (1997) and Bär (2006), this is particularly evident not only in vertical cooperation systems but also in diagonal interdependencies. Pennings (1980) talks about "symbiotic" interdependencies. Michálková (2011) draws attention to not only the problems but also the opportunities resulting from the diversity of subjects in cross-industry regional networks.

The creation of specific territorial interaction and cooperation relations enables a network approach. Networks are a form of coordination in a polycentric society between the market and hierarchy, they bring flexibility to regional structures and enable the use of those synergies that arise from the cooperation of different interest groups (Backhaus, 1993; Breda et al., 2006; Meriläinen & Lemmetyinen, 2011; Sydow, 1992). Genosko (1999) says, among other things, that networks improve the economic performance of a region and increase its competitiveness. The authors differ in emphasizing some of the aspects of the motives and benefits of cooperation. Marketing motives are presented by Buhalis (2003), Fayall and Garrod (2005), Gúčik (2020), Palatková (2011). Easier access to the market, common marketing communication, the faster and more efficient adaptation of production to market requirements as well as possible benefits in the area of better purchasing conditions are emphasized. There is a more efficient redistribution of existing resources but networks also create additional resources and new values. Cooperation supports the creativity and innovation of partners, technological interdependencies require common product and process innovations (El-Chaarani et al., 2021; El-Chaarani & Raimi, 2022; Kubičková & Benešová, 2022). Networks allow concentration on their own key competencies and thereby specialization of partners and better satisfaction of visitors' needs. According to Scott et al. (2008), an essential prerequisite for innovation is an understanding of how destinations are obtained and shared as well as how the knowledge is used. The focus is primarily on network analysis in the tourism industry, which according to them, can clarify the process of knowledge sharing in the destination and thereby significantly contribute to the competitiveness of the destination. Reinhold et al. (2018) and El-Chaarani and Raimi (2021) consider the initiation and implementation of challenging innovation projects with the current competition and cooperation of entities in the destination to be a great challenge. Cooperation as know-how transfer is emphasized by Wang and Fesenmaier (2007), Palatková (2011), Gursoy et al. (2015). Economic and financial motives for cooperation are highlighted in the works of Fayall et al. (2000), Lazzeretti and Petrillo (2006), Saretzki et al. (2002), Beritelli (2011) and Vrontis et al. (2022). The authors agree that not only production and transaction costs can be reduced through collaboration but also savings can be achieved from the scope concerning the offer and also from the range concerning the demand. The information and communication costs are reduced as a result of the use of inter-organizational information systems. It is possible to achieve a reduction in control costs due to the reduction of opportunistic behavior of partners by generating mutual dependencies between them. In complex projects networks serve to distribute risk among several network partners and ensure better access to financial resources (Fang et al., 2023).

Although “collaboration is generally assumed to be viewed positively” (Reinhold et al., 2018), networks cannot be understood only as harmonious partnerships. In addition to cooperation, common interests and goals, diverse conflicts based on substantive and/or human aspects are represented in networks to varying extents (Michálková et al., 2022). Naturally, there is a competitive struggle, the promotion of one's own interests and opportunistic behavior towards partners occurs, according to Gáll and Strežo (2019). Entities cooperating in the network do not give up their autonomy, which means that they also do not give up their own interests. However, the mentioned phenomena do not have only a negative character, they are a prerequisite and one of the manifestations of the viability of the network and its members, its flexibility and internal dynamics. The authors draw attention to the possible misuse of the network, which becomes a tool for interest groups to strengthen their own power (Raich, 2006), especially in the case of possession of strategically important limited, irreplaceable or hard-to-replace resources. “Dominant stakeholders tend to control destination governance systems, less powerful ones are not actively included” (Zee et al., 2017). Not only the size of the interest groups and their financial power play a role in the imbalance of the interest groups' positions. The legislative power or the position of the entity in the offer of the destination, its ownership of strategic resources or having a key competence in the destination are also essential. Even though several authors draw attention to the disadvantages and barriers of cooperation (Fayall & Garrod, 2005; Axelrod, 1998; Spremann, 1990; Morrison, 2013; Fletcher et al., 2018; Holesinska, 2013) from subjective barriers (fear, mistrust, concerns about inequality in the relationship) through barriers of the political environment to goal barriers (e.g. lack of capital, high transaction costs) and there is a questionable ratio between the benefits of cooperation and the costs associated with it, the importance of cooperation and its need is obvious from the nature of the essence of tourism. Networks also arise as a reaction to a positive stimulus from micro- and macro-environments of the destination but also as a reaction to negative phenomena in the destination and its macro environment (Motsa et al., 2021), for example, as an effort to react and solve negative manifestations of a decline in growth or stagnation in the source markets. Several networks involved in tourism usually operate in the destination, either as a manifestation of the activity of entities in the destination or as an effort to use available public resources for tourism development. Michálková and Gáll (2021) draw attention to the fragmentation of management in destinations and the questionable operation of several identical/similar institutionalized networks. They are often mutually competing for activities, in one destination under different "headings" and the questionable meaningfulness of their support from public sources for tourism development.

When examining cooperation relationships between tourism entities, authors mainly examine their qualitative aspect (Jamal & Getz, 1995; Pálenčíková, 2008; Wang & Fesenmaier, 2007, Pechlaner et al., 2012b and others). A quantitative study was carried out by Scott et al. (2008), Beritelli (2011), Beritelli et al. (2013), Gajdošík (2019) and others. The importance of relations for the regional development of tourism is also confirmed by Bornhorst et al. (2010). According to these authors, an organization of destination management whose leaders and managers focus on the relations of stakeholders has a much greater chance of success. Buhalis (2000) states that the development and implementation of strategic goals in destination depends on the relations between the stakeholders. Relationships in the network are a complex and interdisciplinary issue but the authors emphasize the need to create a platform for regular communication, which is intended to help to improve the quality of relationships in order to create space for cooperation and also to weaken the barriers to cooperation (Costa & Lima, 2018) to varying extents and in various contexts. Selin and Chavez (1995) and Gursoy et al. (2015) as well as many others consider the communication between the members of the partnership and its level to be one of the key factors of a functioning partnership in tourism in the destination. They confirm that effective communication is a necessity to achieve the satisfaction of network members. They also emphasize the need for strong leadership to achieve stakeholder engagement. Regional networks and territorial proximity of cooperating partners make coordination of interests and competencies of regional interest groups, including the dynamic capabilities in tourism business (Nguyen et al., 2022), for example, through personal contact, much easier. Shared identity, common regional values and norms can reduce the uncertainties of network partners and promote social integration in the network (Zhou et al., 2022). Territorial proximity has positive effects on the stability of relations in the network but on the other hand, there is also a risk of deterioration of the built structures.

The diversity of entities involved in the development of tourism is the cause of the amount of demand for destination management and the reason for its several limitations (Buhalis, 2000). Volgger and Pechlaner et al. (2012a) consider the networking ability of DMOs to be important for their acceptance among stakeholders. Also, according to D’Angella and Go (2009), networking ability is considered a primary prerequisite for a positive evaluation of DMO performance. Hristov (2014) relates "the wider destination management network" to the support of the visitor economy and the future sustainability of DMOs, while he mentions co-creating destination development being “a holistic, cross-organizational approach to adopting proactive agendas simultaneously responding to post-austerity challenges and the opportunities to further develop destinations through strategic alliances”.

DMOs are directly referred to as leadership networks in destination (Zehrer et al., 2014). Hristov and Zehrer (2015), Hristov et al. (2018) state that DMOs as leadership networks in the destination represent a common approach leading to the strategic development of the destination and should be seen as a means of removing obstacles that prevent the inclusion of stakeholders in the destination. They talk about introducing the so-called “open door” policy and putting it into practice. More and more authors draw attention to the limited scope of the destination management organization as a manager for tourism service providers as well as for the domestic population. Therefore, they emphasize in particular its coordinating function, stimulating cooperation and representing the interests of stakeholders in the destination (Fayall & Garrod, 2005; Hall, 2011; Heath & Wall, 1992; Pechlaner et al., 2012a; Presenza et al, 2005; Volgger & Pechlaner, 2014).

The authors include marketing activities, especially the creation of a destination product with an orientation to the destination key competencies (Buhalis, 2000; Prideaux & Cooper, 2002; Steinecke, 2013;) and marketing communication, building the brand and image of the destination (Kozak & Baloglu, 2011; Pike, 2009 and many others) among other essential tasks of destination organizations. The reaching of a consensus within the communication campaign as well as raising funds for it is considered to be one of the most difficult tasks of destination management. In several works, the tasks of destination management are emphasized in connection with the strategic planning of tourism development. Fesenmaier and Xiang (2017) understand destination management as a set of coordinated techniques, tools and measures applied in the planning, organizing, communication, decision-making process and regulation of tourism in a destination. They emphasize increasing competitiveness through cooperative management using common planning, branding and creating a complex product. Destination planning is included among the key functions of destination management by Pearce (2015), Ionescu et al. (2022) and Dwyer et al. (2020). Mason (2020) claims that managing the tourism development in a region is defining the strategy, vision, mission and goals of tourism in the region. Morrison (2013) considers leadership and coordination, planning and research, product creation, marketing communication, fostering partnerships and building relationships with residents to be the main roles of management organizations in a destination. For successful and sustainable destination management, Beritelli et al. (2014) among other things states the ability to create and implement a shared vision for the destination with values and priorities that meet the needs of an increasingly diverse set of stakeholders. Pike (2009) considers management organizations as initiators of planning and research in the destination and highlights the need to identify new opportunities through identifying gaps in the market. Pearce (2015) states that destination marketing, destination branding, and positioning, destination planning, monitoring and evaluation, product development, research, information management and knowledge collecting, organizational responsibility, management and partnership belong among the key functions of destination management. The importance of planning is also discussed by Bornhorst et al. (2010). The importance of the mission and vision of the destination as well as the goals are emphasized by many authors, among others are Selin and Chavez (1995); Marzano and Scott (2009), Morrison (2013).

Although the authors consider strategic planning as one of the important tasks in destination management and talk about the need for an integrated strategy in connection with DMO leadership, Reinhold et al. (2018) look at it critically. They emphasize the need for a differentiated perception and approach to strategic work in the destination. They reflect on the impact and time validity of "big" strategies and the reality of strategic initiatives. According to Beritelli et al. (2015), managers as well as government officials often use “destination management” only as a password or phrase when introducing a new planning processes or to legitimize individual initiatives. However, this leads to rather frustrating results, such as disharmony, where interest groups in the destination indirectly or openly disagree with terms that are neither objectively defined nor explained. A "big mix" emerges, in which all interest groups and stakeholder groups with conflicting interests are assumed to participate simultaneously in strategic processes and they must reach a consensus. A new framework for tourist destination is proposed by Beritelli et al. (2020), combining three concepts and related foundational theories: visitor flows, trajectories, and corridors. They extend the flow-based view of destinations by proposing this alternative, demand-driven view of tourism planning.

In addition, the question of strategic work in a destination arises if there is no single strategic planner with hierarchical legitimacy. Destinations must permanently be adapted to changes in the macro-environment and require flexibility from destination networks in response to new challenges (Kreilkamp, 2015). Reinhold et al. (2018) shift the definition of destination to a market-oriented production system. They point out the pressure exerted on destination management organizations in achieving destination performance. At the same time, they talk about the problematic requirement to document the effectiveness of the spent public resources as well as the added value of their activities concerning visitors as well as interest groups in the destination. They express the need to find new work as well as organizational forms to achieve greater flexibility in fulfilling their management and marketing tasks. All activities in the destination should be linked to the key task of being sustainable, efficient and a tourist-oriented creation of experiences for visitors. The authors address the issues of destination management as multiple networks and production systems based on leadership (leadership and shared leadership), the role of destination management organizations, interest groups and institutions in networks, as well as the role of trust and leadership in polycentric networks.

Methodology

The main goal of the presented article is threefold: (1) identifying and measuring the perceived rate of problems in development management in the tourism industry, (2) identifying and measuring the perceived rate of problems of cooperation between the interest groups in the tourism industry, and (3) examining connections between problem rates of development management and cooperation between interest groups in tourism.

Based on the above-mentioned main goal, research questions and hypotheses, which will help us in the comprehensive fulfillment of the goal, were formulated:

-

RQ1: How can problems in development management in tourism be evaluated in the context of tourism development?

-

RQ2: How can the problems of cooperation in tourism be evaluated in the context of tourism development?

-

H1: There is a relationship between problems in the development management of tourism and cooperation in tourism.

Following the goal of the article, we have created a database of experts in the field of regional tourism from Europe, both representatives of the academic sphere and representatives of the practice of regional tourism, i.e. regional tourism organizations that manage tourism development in regions in individual countries. 150 experts from the university environment and 275 experts from practice were contacted, i.e. a total of 425 experts. The return rate of the survey was approximately 22.4%. The basis of the primary survey was 95 experts, of which 46 experts were from the academic environment and 49 experts were from practice. In the context of expert categorization, it can be stated that 60% were from Eastern Europe, 4.2% were from Western Europe, 5.3% were from Northern Europe and 30.5% were from Southern Europe.

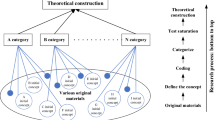

Creation of the research design for tourism development problems

The presented article deals with the issue of problems in the context of tourism development management and the cooperation of interest groups in the tourism industry. The goal is the measurement, i.e. quantitative evaluation of individual problems. Based on the professional literature presented in the literature review section, key problems in the examined problem areas were identified. Eight factors were identified within the field of tourism development management and seven factors were identified within the cooperation of interest groups in the tourism industry. These factors were adjusted to the statements to which the respondents (experts) responded on a five-point bipolar scale (0 – no problem; 4 – a significant problem), which assessed the level of individual problems. Respondents could also choose several answers, which gave them more space to express their professional opinion. In case they chose multiple answers (two multiple self-reported measures), their final rating represents the average value of the chosen answers.

It was necessary to verify their validity and reliability since these are newly created measurement tools. The validity of the research models was ensured by drawing from professional sources as well as consultations with experts. From the point of view of reliability, it was necessary to first verify the reliability within the individual instruments. Due to the nature of the evaluation of the statements (scale evaluation), the reliability estimation coefficient could be used to verify the reliability, while Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega are most often used. In general, McDonald's omega is considered to be better, as Cronbach's alpha is significantly affected by the number of statements and has other limitations (Feißt et al., 2019). It is also advisable to verify (estimate) the reliability within individual statements since these are new measurement tools. The reliability estimate was made with a coefficient, namely McDonald's ω with the help of the "If item dropped" method, the goal of which is to examine whether the reliability estimate changes if the statement is discarded. The results were recorded in Table 1.

General recommendations state that an acceptable value of McDonald's ω is from 0.700 (Lance et al., 2006). Based on the results recorded in Table 1, it can be concluded that both instruments are reliable. Table 1 also shows that it makes no sense to eliminate any statement within individual instruments. An increase in the reliability estimate can be observed for some statements ("high influence of private investors" factor). However, this is a relatively small value that is covered by the confidence interval (95% CI lower/upper bound).

Results and discussion

In the following part, the paper focuses on answering research questions and hypotheses that will help in fulfilling the goal.

-

RQ1: How can problems in development management in tourism be evaluated in the context of tourism development?

Average values and standard deviations for individual problems were recorded in Table 2. In the context of the individual problems of managing tourism development, it is possible to conclude that all researched problems reach the middle value of the scale on average.

The measurement tool consists of eight factors based on professional literature, to which the respondents (experts) responded based on the scale of the significance of the problem, while the intensity of the significance assessment ranged from 0 points (absolutely insignificant/negligible problem) to 4 points (significant problem/very significant problem). It follows from the above that the resulting value of the instrument as a whole, will range from 0 to 32 points. The average measured value of the module was at the level of 17.14 points (with a standard deviation of 7 points), which represents roughly 53.56%. The median is at the level of 18 points and the modus is at the level of 22 points. From the above, it can be concluded that managing tourism development represents an average according to the above-average problem in the development of tourism regions.

The values of the average of the examined sub-problems related to managing the development of tourism in the region do not differ significantly. The biggest problem appears to be the "absent/insufficient systematic management of tourism development in the region", then the "non-existent or poor common vision and current concept of tourism development in the region" and the "insufficient legislative competencies of the regional management organization". Each of the examined countries or even regions, has different management systems for tourism development at the regional level and its legislative framework. Despite this, the insufficient legislative competencies of DMOs are perceived as one of the most prominent problems in European countries. Systematicity in management is disturbed by the changing political environment and weakened continuity, especially in regional organizations connected to public administration. It can be assumed that more developed countries have a more stable system of organization of management as well as financing of development activities. A problem for some countries can also be the changing territorial definition of regions, which can cause instability in management and a non-existent vision or concept of development. The existence, as well as quality of strategic documents, directly depends on the professionalism of management as well as communication with the regional interest groups and the ability to accept the strategic direction of the region in practice.

On the contrary, respondents consider "non-existent or insufficiently functioning regional organization covering the tourism development in the whole region" to be less problematic. It is not so much the existence of the organization that is essential but its real functioning in systematic management. The less problematic perception that "the concept of tourism development plays no role or a minimal role in the tourism development in the region" may be related to low expectations from concepts (this statement is also supported by the statements of Reinhold et al., 2018). On the other hand, the reason may be that the implementation of the created common concept of development is often supported by public resources or the concept also fulfills other tasks valued by stakeholders, as a result of which this aspect is perceived as less prominent.

-

RQ2: How can problems of cooperation in tourism be assessed in the context of tourism development?

A valid scientific theory was used to evaluate the rate of cooperation problems in tourism. Based on the theory, a tool was created covering seven generic areas of problems of cooperation between interest groups in the tourism industry. Average values and standard deviations for individual problems were recorded in Table 3.

The measurement tool consists of seven statements/factors that cover the issue of cooperation between interest groups in the tourism industry within the region. Due to the scale used and the number of items, the range of results ranges from 0 to 28 points. The average measured value was at the level of 14.77 points with a standard deviation of 5.03 points. The median value is 15 points and the mode is at the level of 19 points. It follows from the above that the problem represents approximately 52.75%, which represents an average that is slightly above the average value.

According to the average values, the respondents consider the biggest problems related to the cooperation of interest groups in the region to be mainly the "low involvement of other related sectors in tourism activities" and the "insufficient cooperation of tourism business entities in the region with each other". It is difficult to involve related sectors in cooperation with the tourism development in the region. Usually, the sectors which live from tourism to varying degrees, are suppliers for tourism service providers or they are providers of subsequent or additional services for tourists or they create an offer of atypical tourism products as part of normal consumption (Guaita Martínez et al., 2022). Greater involvement of related sectors requires professional and systematic work of regional management supported by its legislative and financial competencies. Its achievement is of course easier in the case of mandatory membership of the interest groups, directly and indirectly, benefiting from the development of tourism in the DMO, in contrast to countries/regions with voluntary entry. The low involvement of related sectors in tourism can be considered a sign of the developing regional management and cooperation in countries that started to develop destination management only after the implementation of democratic changes in society. Insufficient cooperation between business entities in the tourism industry is a natural phenomenon, especially among entities in direct horizontal and possibly diagonal competitive positions. Nevertheless, cooperation on the common goal of developing tourism in the region is expected. Among other things, opportunities to implement projects requiring cooperation or projects that are directly conditioned by cooperation, can contribute to their cooperation.

Experts see the smallest problem when it comes to the influence of private investors. Private investors bring capital to the region and support the development of tourism infrastructure. Experts in the survey perceive their positive effects on the development of tourism in the region rather than a possible negative influence consisting of the assertion of the power of strong investors as owners of the supporting resources.

-

H1: There is a relationship between problems in the development management of tourism and cooperation in tourism.

When examining the relationship between the models, Pearson's correlation coefficient was used (due to the nature of the variables). A strong positive relationship can be established (cor. = 0.656). At the same time, the validity of this coefficient was verified within the framework of inductive statistics (alpha = 0.05; p-value = < 0.001).

The relationship between problems in the management of tourism development and cooperation is obvious and can be assumed to be mutual. The level of management affects the ability and willingness of stakeholders to cooperate and conversely, the cooperation of stakeholders affects the work in development management and is a necessary prerequisite for the prosperity of tourism in the region. Intensive and productive cooperation of various stakeholders in the region is an essential factor in the success of managing tourism in the region, while on the other hand, quality management initiates opportunities for cooperation and encourages the implementation of common projects.

The in-depth analysis also focused on examining the relationship between individual problems within the models. Due to the nature of the data, the Spearman correlation coefficient was used. Since there were 15 variables, the final output is 120 correlation coefficients. Of course, 15 correlation coefficients, which represent the correlation of a variable with the same variable, reach a value of 1 (perfect correlation) but these values have no interpretative meaning for scientific research. Therefore, it is appropriate to focus only on 105 correlation coefficients. For the sake of clarity, the mentioned correlation coefficients were recorded in a clear chart of the Heatmap type (Fig. 1).

As can be seen from Fig. 1, all correlation coefficients are positive, so positive correlation rates can be stated. Their intensity varies. The darker the color, the stronger the correlation. As can be seen, the strongest relationship was observed for statements A7 with A8 and A6 with A8, i.e. the most strongly affected of the observed problems are "the concept of tourism development plays no role or a minimal role in the development of tourism in the region" or "non-existing or poor common vision and current concept of tourism development in the region" and "problematic agreement on common goals and priorities of tourism development in the region". It is a link within one model A for both connections. Problematic agreement on common activities is caused by the diversity of interest groups—stakeholders in the region and can be directly reflected in the quality of the processing of concepts and strategic documents related to its compromise proposals or proposals acceptable to the relevant entities—the actual implementers of the concept. If the concept is not processed in this way, then it can be assumed that this is one of the factors of its none or minimal impact on the development of tourism or its non-existence caused by the inability/impossibility to agree on joint strategic activities. Once again, the importance of systematic and continuous work with subjects in the region is shown and if it does not work, the region is struggling with a serious problem. The need for internal marketing and the coordination function of regional tourism organizations is confirmed in the literature.

Between models, the strongest relationship can be seen between B3 and A8 and subsequently with A6, i.e. between "insufficient cooperation of tourism business entities in the region with the regional management of tourism" and "problematic agreement on common goals and priorities of tourism development in the region" as also with "non-existent or poor common vision and current concept of tourism development in the region". Business entities play a role in the development of the tourism, their interests are of course, partially different from the interests of other entities, especially from the public and non-profit sectors. However, they are an engine of development, an investor and an economically minded entity. The problem of agreeing on common strategic goals in such a diverse network causes the lack of interest of strong business entities in cooperation and consequently, the impossibility of developing a common vision and concept of tourism development or their poor quality and non-acceptance, especially among the most powerful stakeholders. In order for a regional tourism organization to be an economically strong partner business entity, it must bring clear benefits from cooperation with it, which may have a different nature but ultimately have a positive impact on the economy of the company. The relationship between A3 and B4, i.e. the "insufficient legislative competencies of the regional management organization" and "insufficient cooperation of tourism business entities in the region with each other", proved to be the least strong relationship between models overall. Even if the relationship is less strong, the legislative competences of regional tourism organizations can influence or support the mutual cooperation of business entities, for example their financial capacity and work with public resources or resources obtained on the basis of legislative authorization (e.g. accommodation tax, membership fees or mandatory membership fees and among other things). However, the survey showed that this connection is at a minimum tight, respectively, due to the label "insufficient legislative competencies of the regional management organization" as one of the three biggest problems, legislative competencies are insufficient to make the effect on the mutual cooperation of business entities obvious.

Conclusion

The presented article focuses on the examination of two important areas within the framework of regional tourism development problems, namely development management and cooperation of regional tourism interest groups. For the needs of quantifying individual problems, scale tools for measuring these measures were created based on professional literature. The article is supported by a primary survey in which 425 experts from practice and the academic sphere were approached. The sample in the final phase consisted of 95 experts. The measurements showed an average to a slightly above-average assessment of individual problem areas in the development of regional tourism. The strong positive relationship between development management and cooperation confirms the correctness of the literature devoted to this issue and studies analyzing these problems. Common management of the region supported by the cooperation of various stakeholders in the region is the basis of its prosperity.

Measuring and developing the perceived intensity of the problem of individual parameters in both models can be a tool for determining key priorities and a stimulus for the correct setting of processes supporting more effective management and networking in the region. The possibility of comparing countries and searching for reasons for differences in the values of statements/parameters and possible inspirations for solving problems in countries/regions with a lower intensity of problems is interesting. It mainly deals with the field of regional tourism management but also with the national level in relation to its competencies and the possibilities of influencing regional development from the point of view of the examined parameters.

The position of tourism in the economy of European countries and their regions is different, as they have developed different systems of regional management. Therefore, even the average values for the entire sample of respondents have a limited informative value. The strength of the connection between individual parameters in the model and between models in different countries and regions can also be different. A comparison of countries/regions with mature destination management and countries/regions that are in the phase of building destination management, could bring interesting results. However, the model can be used individually for individual countries/regions and compared with average values or to monitor the perception of problems over time.

This paper also contains certain limits for the examination it carried out. The achieved results can be stated only within Europe. In the future, it would also be appropriate to investigate differences within individual European regions or countries depending on the level of tourism development, the organizational ensuring of tourism at the regional level as well as the level of socio-economic development of regions/countries. In the context of the selection of several options in measuring devices by some experts, it can be considered that it would be appropriate to use a wider range of assessment of the perception of problems in the future, which would achieve higher data sensitivity. This paper focuses on only two problem areas within regional tourism development. In future research, it would be appropriate to examine other areas as well, which can lead to the creation of a complex model of development problems. In addition to this issue, other aspects related to, for example, development financing, use of public resources, development sustainability or destination marketing could complete the model with another crucial aspect of tourism in the region.

References

Axelrod, R. (1998). Die Evolution der Kooperation. Scienta Nova Oldenbourg.

Backhaus, K. (1993). Strategische Allianzen und strategische Netzwerke. Wirtschaftswissenschaftliches Studium : WiSt ; Zeitschrift für Studium und Forschung, 22(7), 330–334.

Bär, S. (2006). Ganzheitliches Tourismus-Marketing. Die Gestaltung regionaler Kooperations-beziehungen. Deutscher Universitätsverlag.

Beritelli, P. (2011). Cooperation among prominent actors in a tourist destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(2), 607–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.11.015

Beritelli, P., Strobl, A., & Peters, M. (2013). Interlocking directorships against community closure: A trade-off for development in tourist destinations. Tourism Review, 68(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371311310057

Beritelli, P., Bieger, T., & Laesser, Ch. (2014). The new frontiers of destination management: Applying variable geomertry as a function-based approach. Journal of Travel Research, 53(4), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513506298

Beritelli, P., Reinhold, S., Laesser, C., & Bieger, T. (2015). The St. Gallen model for destination management. IMP-HSG.

Beritelli, P., Reinhold, S., & Laesser, C. (2020). Visitor flows, trajectories and corridors: Planning and designing places from the traveler’s point of view. Annals of Tourism Research, 82, 102936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102936

Bieger, T. (2008). Management von Destinationen. Oldenbourg.

Bornhorst, T., Ritchie, J. R. B., & Sheehan, L. (2010). Determinants of tourism success for DMOs and destinations: An empirical examination of stakeholders´perspectives. Tourism Management, 31(5), 572–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.06.008

Breda, Z., Costa, R., & Costa, C. (2006). Do clusters and networks make small places beautiful? The case of Caramulo (Portugal). In L. Lazzeretti & S. C. Petrillo (Eds.), Tourism local systems and networking (1st ed.). Routledge.

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 22(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

Buhalis, D. (2003). eTourism: Information Technology for Strategic Tourism Management. Pearson Education Limited. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.455

Calero, C., & Turner, L. W. (2020). Regional economic development and tourism: A literature review to highlight future directions for regional tourism research. Tourism Economics, 26(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619881244

Costa, T., & Lima, M. J. (2018). Cooperation in tourism and regional development. Tourism & Management Studies, 14(4), 50–62.

D’Angella, F., & Go, M. F. (2009). Tale of two cities´collaboration tourism marekting: Towards a theory of destination stakeholder assessment. Tourism Management, 30(3), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.07.012

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Dwyer, W. (2020). Tourism economics and policy (2nd ed.). Channel View Publications. Retrieved December, 1, 2022 from https://www.perlego.com/book/1344773/tourism-economics-and-policy-pdf

El Chaarani, H., & Raimi, L. (2021). Determinant factors of successful social entrepreneurship in the emerging circular economy of Lebanon: Exploring the moderating role of NGOs. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 14(5), 874–901. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-08-2021-0323

El Chaarani, H., & Raimi, L. (2022). Diversity, entrepreneurial innovation, and performance of healthcare sector in the COVID-19 pandemic period. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(S1), 2–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2808

El Chaarani, H., Vrontis, P. D., El Nemar, S., & El Abiad, Z. (2021). The impact of strategic competitive innovation on the financial performance of SMEs during COVID-19 pandemic period. Competitiveness Review, 32(3), 282–301. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-02-2021-0024

Elvekrok, I., Veflen, N., Scholderer, J., & Sørensen, B. T. (2022). Effects of network relations on destination development and business results. Tourism Management, 88, 104402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104402

Fang, R., Liao, H., Xu, Z., & Herrera-Viedma, E. (2023). Risk assessment in project management by a graph-theory-based group decision making method with comprehensive linguistic preference information. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(1), 86–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2070772

Fayall, A., & Garrod, B. (2005). Tourism marketing: Collaborative approach, 18. Channel View Publications.

Fayall, A., Oakley, B., & Weiss, A. (2000). Theoretical perspectives applied to inter-organisational collaboration on Britain´s Inland waterways. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 1, 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1300/J149v01n01_06

Feißt, M., Hennigs, A., Heil, J. Moosbrugger, H., Kelava, A., Stolpner, I., Kieser, M., & Rauch, G. (2019). Refining scores based on patient reported outcomes – statistical and medical perspectives. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0806-9

Fesenmaier, D. R., & Xiang, Z. (2017). Design science in tourism: Foundations of destination management. Springer International Publishing.

Fletcher, J., Fyall, A., Gilbert, D., & Wanhill, S. (2018). Tourism. Principles and practice (6th ed.). Pearson.

Friedman, A., & Miles, S. (2006). Stakeholders: Theory and practice. Oxford University Press.

Gajdošík, T. (2019). Manažérske organizácie v cieľových miestach cestovného ruchu. Belianum.

Gáll, J., & Strežo, M. (2019). Quantitative analysis of environment potential for cluster development in tourist regions of Slovak Republic. Geographica Pannonica., 23(3), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.5937/gp23-21375

Genosko, J. (1999). Netzwerke in der Regionalpolitik. Schüren Verlag.

Guaita Martínez, J. M., Martín Martín, J. M., Salinas Fernández, J. A., & Ribeiro Soriano, D. E. (2022). Tourist accommodation, consumption and platforms. International Journal of Consumer Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12881

Gúčik, M. (2020). Cestovný ruch v ekonomike a spoločnosti. Wolters Kluwer.

Gursoy, D., Saayman, M., & Sotiriadis, M. (2015). Collaboration in tourism businesses and destinations. A Handbook. Emerald Group.

Hall, D. R. (2011). Tourism development in contemporary Central and Eastern Europe: Challenges for industry and key issues for researches. Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography, 5(2), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.5719/hgeo.2011.52.5

Heath, E., & Wall, G. (1992). Marketing tourism destinations: A strategic Palnning approach. Wiley.

Holesinska, A. (2013). DMO – A dummy-made organ or a really working destination management organization. Czech Journal of Tourism, 2(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.2478/cjot-2013-0002

Hristov, D. (2014). Co-creating destination development in the post- -austerity era: Destination management organisations and local enterprise partnerships. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 21(3), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.34624/rtd.v3i21/22.11935

Hristov, D., & Ramkinssoon, H. (2016). Leadership in destination management organisations. Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 230–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.08.005

Hristov, D., & Zehrer, A. (2015). The destination paradigm continuum revisited: DMOs serving as leadership networks. Tourism Review, 70(2), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2014-0050

Hristov, D., Minocha, S., & Ramkissoon, H. (2018). Transformation of destination leadership networks. Tourism Management Perspectives Journal, 28, 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.09.004

Ionescu, R. V., Zlati, M. L., Antohi, V. M., Stanciu, S., Burciu, A., & Kicsi, R. (2022). Supporting the tourism management decisions under the pandemic’s impact. A new working instrument. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2053361

Jamal, T., & Getz, D. (1995). Collaboration theory and community tourism palnning. Annals of Tourism Research, 1, 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3

Kozak, M., & Baloglu, S. (2011). Managing and marketing tourist destinations: Strategies to gain a competitive edge. Routledge.

Kreilkamp, E. (2015). Destinationsmanagement 3.0 - Auf dem Weg zu einem neuen Aufgabenverständnis. Zeitschrift für Tourismuswissenschaft, 7(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1515/tw-2015-0206

Kubičková, V., & Benešová, D. (2022). The Innovation in Services and Service Economy. Wolters Kluwer.

Kvasnová, D., Gajdošík, T., & Maráková, V. (2019). Are partnerships enhancing tourism destination competitiveness? Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 67(3), 811–821. https://doi.org/10.11118/actaun201967030811

Laesser, Ch., Stettler, J., Beritelli, P., & Bieger, T. (2021). AIEST Consensus on tourism and travel in the SARS-CqoV-2 era and beyond. AIEST. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://www.aiest.org/news/covid-reports/

Lance, C. E., Butts, M. M., & Michels, L. C. (2006). The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria: What did they really say? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284919

Lazzeretti, L., & Petrillo, S. C. (2006). Tourism local systems and networking. Elsevier.

Lee, T. J., Riley, M., & Hampton, M. P. (2008). Conflict in tourism development. Kent Businss School – Working Paper Series, 170, 1–37. Retrieved November 26, 2022, from https://www.academia.edu/189758/Conflict_in_Tourism_Development

Marzano, G., & Scott, N. (2009). Power in destination branding. Annals of Tourism Research, 36, 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.01.004

Mason, P. (2020). Tourism impacts, planning and management. Routledge.

Meriläinen, K., & Lemmetyinen, A. (2011). Destination network management: A conceptual analysis. Tourism Review, 66(3), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371111175302

Michálková, A. (2011). Strategické vnímanie regionálnych sietí v cestovnom ruchu so zohľadnením ich rozporuplných efektov. Ekonomický časopis = Journal of economics: journal for economic theory, economic policy, social and economic forecasting, 59 (3), 310–324. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://www.sav.sk/journals/uploads/0913102103%2011%20Michalkova-RS.pdf

Michálková, A., & Gáll, J. (2021). Institutional provision of destination management in the most important and in the crisis period the most vulnerable regions of tourism in Slovakia. European Countryside, 13(3), 662–684. https://doi.org/10.2478/euco-2021-0014

Michálková, A., Gáll, J., & Özoğlu, M. (2022). Regional Economics of Tourism - Selected Problems = Ekonomika cestovného ruchu v regióne - vybrané problémy. Wolters Kluwer CZ. Retrieved November 4, 2022, from https://of.euba.sk/veda-a-vyskum/publikacna-cinnost/publikacie-autorov-of/1007-a-michalkova-et-al-economics-of-tourism-regional-aspects

Mira, M. R., Moura, A., & Breda, Z. (2016). Destination competitiveness and competitiveness indicators: Illustration of the Portuguese reality. Téknhne, 14, 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tekhne.2016.06.002

Morrison, A. (2013). Marketing and managing tourism destination. Routledge.

Motsa, A., Rybakova, S., Shelemetieva, T., Zhuvahina, I., & Honchar, L. (2021). The effect of regional tourism on economic development: Case study: The EU countries. International Review, 1–2, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.5937/intrev2102069M

Ness, H., Aarstad, J., Haugland, S. A., & Grønseth, B. O. (2014). Destination development: The role of interdestination bridge ties. Journal of Travel Research., 53(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513491332

Nguyen, H. T., Pham, H. S. T., & Freeman, S. (2022). Dynamic capabilities in tourism businesses: antecedents and outcomes. Review of Managerial Science, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00567-z

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2016). Stakeholders’ views of enclave tourism. A grounded theory approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 40(5), 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013503997

OECD. (2012). OECD tourism trends and policies 2012. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/tour-2012-en

Palatková, M. (2011). Marketingový management destinací. Grada Publishing.

Pálenčíková, Z. (2008). Spolupráca a partnerstvo v cestovnom ruchu. Ekonomická revue cestovného ruchu, 41(2), 67–77.

Pearce, D. G. (2015). Destination management in New Zealand: Structures and functions. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2014.12.001

Pechlaner, H., Herntrei, M., Pichler, S., & Volgger, M. (2012a). From destination management towards governance of regional innovation systems – the case of South Tyrol, Italy. Tourism Review, 67(2), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371211236123

Pechlaner, H., Volgger, M., & Hentrei, M. (2012b). Destination management organisations as interface between destination governance and corporate governance. An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2011.652137

Pennings, J. M. (1980). Environmental influences on the creation process. In J. R. Kimberly, & R. H. Miles (Eds.), The organizational life cycle: Issues in the creation, transformation, and decline of organizations (pp. xxii, 492). (The Jossey-Bass social and behavior science series). Jossey-Bass.

Pike, S. (2009). Destination brand positions of a competitive set of near-home destinations. Tourism Management, 30(6), 857–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.12.007

Presenza, A., Sheehan, L., & Ritchie, J. R. (2005). Towards a Model of the Roles and Activities of Destination Management Organizations. Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure Science, 1, 1–16. Retrieved November, 27, 2022, from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Towards-a-model-of-the-roles-and-activities-of-Presenza-Sheehan/a2918b4eb532095d919582aa0910be6963c92436

Prideaux, B., & Cooper, C. (2002). Marketing and destination growth: A symbiotic relationship or simple coincidence? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670200900103

Raich, F. (2006). Governance räumlicher Wettbewerbseinheiten. Deutscher Unversitäts – Verlag.

Reinhold, S., Laesser, Ch., & Beritelli, P. (2018). Impulse für die Forschung zum Management und Marketing von Destinationen: Erkenntnisse aus sechs Jahren ADM Forum. Retrieved December, 1, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322636282_Impulse_fur_die_Forschung_zum_Management_und_Marketing_von_Destinationen_Erkenntnisse_aus_sechs_Jahren_ADM_Forum/citation/download

Saretzki, A., Wilken, M., & Wöhler, Kh. (2002). Lernende Tourismusregionen: Vernetzung als strategischer Erfolgsfaktor kleiner und mittlerer Unternehmen. LIT Verlag.

Scott, N., Baggio, R., Cooper, Ch. (2008). Network analysis and tourism: From theory to practice. Cromwell Press Ltd. Retrieved November, 20, 2022, from https://www.iby.it/turismo/papers/book_nets.pdf

Selin, S., & Chavez, D. (1995). Developing an evolutionary tourism partnership model. Annals of Tourism Research, 22, 884–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00017-X

Sheehan, L., & Ritchie, J. R. (2005). Destination stakeholders: Exploring identity and salience. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(3), 711–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.10.013

Spremann, K. (1990). Asymmetrische Information. Zeitschrift fuer Betriebswirtschaft, 5/6/1990, 561–586. Retrieved November, 20, 2022, from https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/31925/1/61asy.pdf

Steinecke, A. (2013). Destinationmanagement. UVK Verlagsgesellschaft.

Sydow, J. (1992). Strategische Netzwerke. Evolution und Organisation. Gabler.

UNWTO. (2007). A practical guide to tourism destination management. World Tourism Organisation. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284412433

UNWTO. (2019). Guidelines for institutional strengthening of destination management Organizations (DMOs) – Preparing DMOs for new challenges. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284420841

Volgger, M., & Pechlaner, H. (2014). Requirements for destination management organisations in destination governance: Understanding DMO success. Tourism Management, 41, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.09.001

Vrontis, D., El Chaarani, H., El Nemar, S., EL-Abiad, Z., Ali, R., & Trichina, E. (2022). The motivation behind an international entrepreneurial career after first employment experience. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 28(3), 654–675. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2021-0498

Wang, Y., & Fesenmaier, D. (2007). Collaborative destination marketing: A case study of Elkhart county, Indiana. Tourism Management, 28(3), 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.02.007

Wilson, D. T. (1995). An integrated model of buyer-seller relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23, 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207039502300414

Wöhler, K. (1997). Marktorientiertes Tourismusmanagement. Springer.

Zee, E., Borg, J., Vanneste, D. (2017). The Destination Triangle. In N. Scott, M. De Martino & M. Van Niekerk (Eds.), Knowledge Transfer to and within Tourism. Academic, Industry and Government Bridges (pp. 167–188). Emerald Publishing Limited. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/doi/10.1108/S2042-144320178

Zehrer, A., Raich, F., Siller, H., & Tschiderer, F. (2014). Leadership networks in destinations. Tourism Review, 69(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2013-0037

Zhou, L., Huang, H., Chen, X., & Tian, F. (2022). Functional diversity of top management teams and firm performance in SMEs: A social network perspective. Review of Managerial Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00524-w

Acknowledgements

This contribution is a part of the project KEGA no. 034EU-4/2020” Content and technical innovation approaches to teaching Regional Tourism”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Michálková, A., Krošláková, M.N., Čvirik, M. et al. Analysis of management on the development of regional tourism in Europe. Int Entrep Manag J 19, 733–754 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00840-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00840-x