Abstract

Every entrepreneur faces barriers when they engage in entrepreneurial activities and for every entrepreneur, their utmost goal is to succeed d in their endeavors. However, some entrepreneurial ventures fail due to several factors. After the failure, the entrepreneur either relapses or seeks for new entrepreneurial opportunities. The present study conducts a qualitative research synthesis to examine what happens after the occurrence of firm failure and how entrepreneurs manage the experiences from failure. In doing so, the present study analyses already published qualitative studies on failure by conducting a literature search from several electronic databases to capture the qualitative studies published under failure. After the elimination of irrelevant data, 21 relevant articles were identified. The identified articles were analyzed using meta ethnography and grounded formal theory to elaborate on three overarching concepts – the experience and cost of failure, the impact from failure and the outcome of failure. The findings from these analyzed qualitative research offers insight into the ongoing discussions on entrepreneurial failure by identifying recurrent themes and concepts as well as by presenting a conceptual model that describes the entrepreneur’s experiences from failure and how they manage these firm failures. The findings also provide avenues on how future research can contribute to the discussion on failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What happens after a firm fails? Are entrepreneurs able to manage these failures? Have they gained any experience and learnt from their failure? These are a few questions from the numerous studies that look into the aftermath of failure (Ucbasaran et al. 2013; Shepherd 2009; Headd 2003; McGrath 1999; Politis and Gabrielsson 2009; Shepherd et al. 2000). Studies have looked into the causes and consequences of failure, to gain more understanding on the factors that lead to failure as well as the aftermath of failure (e.g., Ucbasaran et al. 2013: Politis and Gabrielsson 2009). Previous research highlight that when entrepreneurs fail, they experience among other things, psychological, social, and financial cost (Ucbasaran et al. 2013; Cope 2011; Shepherd et al. 2000).

Research acknowledges that entrepreneurs feel negative emotions such as grief when their business fails (e.g., Shepherd and Cardon 2009). However, the grieving process can also lead the entrepreneurs to be able to cope with the effects of failure (Singh, Corner and Pavlovich 2007). Research also acknowledges that coping from failure aids entrepreneurs to make sense of the occurrence of failure as well as seek for means to learn from such failure. Moreover, the emphasizes that learning from failure is an important phase entrepreneur have to go through in order to seek for new career opportunities. As a result, entrepreneurs do not just learn from previous mistakes, but also gain new insights, knowledge, information, and experiences from previous venture engagements (Cope 2011; Shepherd and Cardon 2009).

Failure research offers detailed methodological perspectives on the occurrences of failure, the challenges faced by entrepreneurs during the failure experience, the aftermath of failure as well as the cost and outcomes of failure. Accordingly, a few quantitative studies have tried to see the relationship between failure and re-entry and what factors influences new venture engagement after the failure occurrence (e.g., Cardon and McGrath 1999; Nikolić et al. 2019; Politis and Gabrielsson 2009; Ucbasaran et al. 2010). A significant number of qualitative research however, have sought to gain deeper understanding on how and why entrepreneurs manage firm failure and failure influences on new venture performance (e.g., Cardon et al. 2011; Cotterill 2011; Singh, Corner and Pavlovich 2015; Walsh 2017). Given that the circumstances following failure can be complex and unpredictable, it becomes more suitable to apply qualitative methods to gain deeper understandings of the phenomenon, and generate new empirical theory suited for the above phenomenon. Hence, the amount of published qualitative research in understanding the preconditions and consequences of firm failure.

The present study seeks to synthesize understandings from previous qualitative research on what happens after firm failure occurs and how entrepreneurs manage the experiences from failure. Additionally, the study engages in a recent discussion on using qualitative methods as a means to better understand entrepreneurship research and provide new theoretical perspectives in the entrepreneurship field (Suddaby, Bruton and Si 2015). There has been a considerable amount of qualitative study performed that describes the occurrences of firm failure, however there is limited research that analyze and translate findings from each of these studies to ensure rigorous combination of these studies as well as to build and elaborate on previous research on firm failure. A qualitative lens is adopted for this study because it aids to better advance our understanding on the phenomenon of entrepreneurial failure. Moreover, applying a qualitative lens on entrepreneurial failure would yield the identification and development of indigenous concepts and themes that can be used to define and generate theories in examining firm failure. The present study therefore, aims to synthesize these qualitative findings using a combination of formal grounded theory and meta-ethnography. The synthesis aims to provide more understanding on how entrepreneurs manage business failure, to identify and assess core themes in relation to firm failure and the need for future research in this area, and to provide theoretical generalization.

Theoretical background

Firm failure is ‘the cessation of involvement in a venture because it has not met a minimum threshold for economic viability as stipulated by the (founding) entrepreneur’ (Ucbasaran et al. 2013:188). Scholars have typically distinguished failure such as dying firms, discontinued firms, involuntary closure from entrepreneurial exit or firm exit where the entrepreneur voluntarily exit or closes their firm [usually for financial gain] (DeTienne 2010). While exit consist of a decision that may yield financial gain, failure on the other hand involves [sudden] termination of venture due to unrealized short-term goals or unsuccessful business engagement, and insolvency (Shepherd 2009; Headd 2003; McGrath 1999; Politis and Gabrielsson 2009; Shepherd et al. 2000). Failure can occur due to factors caused by the entrepreneurs themselves such as the lack of skills and unrealistic decisions they make, financial limitations as well as from external factors (Ucbasaran et al. 2013; Larson and Clute 1979; Pretorius 2008).

The occurrence of business failure strongly affects an entrepreneur in several ways. This is because the entrepreneurs spend time to birth, found, grow and nurture their venture. As a result, entrepreneurs may hold on to their ventures longer in order to avoid delay closure (Shepherd et al. 2000). Moreover, when failure occurs, entrepreneurs experience several costs and consequences from such failure. Research is replete with examples of such costs experienced by entrepreneurs when failure occurs including financial cost, social, psychological and physiological cost (e.g., Cope 2011; Shepherd et al. 2009; Shepherd and Haynie 2011). More specifically, entrepreneurs face stigmatization after failure occurrence, where they either isolate themselves from their network or where their networks isolate them. Furthermore, entrepreneurs also go through financial loss from investments, capital and borrowed funds (Cope 2011; Shepherd et al. 2009; Singh et al. 2007). Psychologically, they experience mostly negative emotions as a means to manage the failure occurrence. Research emphasize that negative emotions such as grief is one inevitable consequence that arises from firm failure (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2018; Cope 2011; Hayward et al. 2010; Shepherd and Cardon 2009; Shepherd and Haynie 2011; Ucbasaran et al. 2013), although not all entrepreneurs experience grief in the same way (Jenkins et al. 2014).

In the process of psychological experience, entrepreneurs also make sense and learn from the events leading to failure. Sensemaking occurs when the entrepreneurs make retrospective accounts of the causes of failure, to identify how and why their ventures failed. The sensemaking process can thus drive them into learning from their failure, by taking note of the aspects, decisions, or competences that led to the said failure. In the event of firm failure, studies have shown that sensemaking plays a significant role in the way entrepreneurs manage failure (Cope 2011; Byrne and Shepherd 2015; Sitkin 1992). Because learning from failure is a process that occurs during a period of time, there is usually no specific time frame for entrepreneurs to actually learn from their failed event. Learning from failure aid the entrepreneurs to gain new information, skills and knowledge from their failed business attempt. Moreover, the entrepreneurs can obtain useful lessons from their failure because they do not just identify the cause of failure but also attempt to reflect and make sense of them so as to make certain changes and improvements to avoid making previous mistakes (Cannon and Edmondson 2001; Politis and Gabrielsson 2009).

Entrepreneurs who are able to learn from their failure and gain new insights from the experience, have better possibilities to either exploit new opportunities or start new venture after the failure experience (Yamakawa and Cardon 2015). Previous studies have provided accounts on the influence of failure and the success of starting new venture and subsequent entrepreneurial engagement (e.g. Cope 2011; Minniti and Bygrave 2001; Mitchell et al. 2004; Politis and Gabrielsson 2009).

Taken together, the background posits that after business failure, entrepreneurs seek different means to manage the failure. They go through negative emotions where they grief the loss of their firm, get stigmatized for failure, make sense and learn from their failure and eventually, seek for other opportunities. Although there are different studies that discuss what happens after the firm failure including quantitative investigations and qualitative explorations, results from managing failure is prominent within the qualitative research area, presenting similar conclusions and recommendations. The present study therefore, seeks to synthesize these qualitative findings using a meta-interpretation, which is presented as a combination of grounded formal theory and meta-ethnography. The synthesis seeks to gain more understanding on how entrepreneurs manage business failure, to identify and assess core themes in relation to firm failure and the need for future research in this area, and finally, to provide theoretical generalization.

Methodology

A synthesis of qualitative research

A synthesis of qualitative research allows for translations of findings from each individual study into other studies in the synthesis. It thus involves reinterpretations of findings, which can produce significantly new insights or identify research fields that is already saturated and has reached its highest point of theoretical contribution, where no new development has been made over time is made (Noblit and Hare 1988; Atkins et al. 2008; Finfgeld 1999). This therefore gives the opportunity for research to explore other concepts, topics or themes. Furthermore, when synthesizing qualitative research, proper exanimation is conducted to produce an appropriate translation of the key concepts, conducting relevant empirical studies are taken into account, read repeatedly, and key themes and subject matter noted down. More specifically, the aim for such synthesis is to explicitly identify concepts from previous studies, that were not previously explicit. Thus, providing a complete understanding of the studied phenomenon as well as to bring together several isolated studies through the accumulated understandings from them (Campbell et al. 2012).

The present study focuses on the collective findings on business failure and its consequences for entrepreneurs. For this purpose, a meta-interpretation – a combination of a formal grounded theory (Kearney 2001) and a meta-ethnography (Noblit and Hare 1988; Atkins et al. 2008) – was conducted. A formal grounded theory on the one hand, applies the same structure of the traditional grounded theory approach which seeks to develop higher-level concepts and theory, using constant comparisons of similarities and differences presented in the data (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss and Corbin 1990). The meta – ethnography on the other hand provides new insights by utilizing participants in findings as well as the interpretations from the author (Noblit and Hare 1988), which generally seeks to yield a much richer conceptualization from the qualitative research. The meta-ethnography like the formal grounded theory, preserves the meaning from each qualitative research in the process of analysis and synthesis.

A meta- interpretation synthesizes the findings from multiple qualitative research with the aim of generating higher translations of the phenomenon that is explored to create a more theoretically dense conceptualization (Finfgeld 1999). Synthesizing qualitative findings are becoming more significant as a result of the uprising of qualitative research and its importance in gaining deeper understanding to specific phenomenon thereby encouraging the research in transferring ideas, concepts and metaphors across different studies examining similar phenomenon. This study therefore applies the meta-ethnography to provide procedural guidelines suggested by Noblit and Hare (1988) and the grounded theory provides epistemological and methodological basis implemented for this study (Strauss and Corbin 1990).

Sampling criteria and procedure

The study presents a report from qualitative research. To begin the synthesis, a comprehensive search on entrepreneurial failure and business failure was conducted using computerized sources. Searches were conducted using database such as SCOPUS, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, Web of science (SSCI) and EBSCO. Search words such as Fail*, Failure* Ent* Entre* Business* and Venture* were used to find published articles that captured business failure and entrepreneurial failure. Several inclusion criteria were used to select studies for analysis. First, since the study aimed to address how entrepreneurs manage business and firm failure, the study considered only published articles that focuses on the aftermath of failure and not preconditions or causes of failure. For instance, studies relating to fear of failure, heart failure, entrepreneurial education, and entrepreneurial intentions were excluded in this criterion. Second, non-peer reviewed papers were excluded. Third, the study only focused on the synthesis of qualitative findings, therefore quantitative studies and conceptual /review papers were excluded in the synthesis. However, qualitative studies such as phenomenological studies, ethnographic studies, grounded theory, case studies and studies that explicitly used widely accepted qualitative methods were included. Finally, qualitative studies that did not describe an analytic approach were also excluded in the analysis as it did not meet the requirement suggested by Noblit and Hare (1988).

In addition to the inclusion criteria above, selection processes were conducted in two stages to ensure that relevant articles were selected for analysis. First, after the initial search on the database, title and abstracts were read and screened. Titles and abstracts that did not address the focus of this study were excluded. In addition, duplicate hits and studies within other fields such as medicine, engineering, law, and computer science were also excluded. Second, a follow up was made by full-text screening. Furthermore, since the abstract search may not provide details of potentially relevant studies in relation to entrepreneurial failure, manual searches from the references list of relevant studies were further assessed to identify other relevant articles that were not identified during the initial searches. Nineteen relevant reports were identified after the screening of relevant searches. Table 1 presents the selection process for the present study.

Data analysis, and translation

Data collection was conducted systematically from each report. Reports were read, and notes were made along-side. Further, the categories, texts and themes extracted from the data included but not limited to the authors name and year, research theme/ focus, research questions/aim, study design, method of data collection, sampling, social context, and components from the findings and the authors’ conclusions. Each of the 19 reports were characterized with these categories, summarized and interpreted.

In line with the grounded theory approach, several coding strategies were adopted to identify concepts and categories (Strauss and Corbin 1990). First, the analysis began with the implementation of substantive coding. Here, descriptive and theoretical analysis of the data were conducted using constant comparisons. In doing so, text units, ranging from one sentence to a paragraph were read to make sense of the data. Themes and presented concepts across all studies were identified, clustered into new higher categories. Additionally, for the axial coding, a comparison was made within and across the 21 studies to seek for the relationships and similarities between the categories on the after effect of firm failure. Finally, a selective coding was conducted. Here sub-categories that describes the aftermath of failure were aggregated into core categories. During the analytic synthesizing and translation process, constant iteration was made, and the analysis were documented in memos using specific links to source text and to aid in the construction of a visual representation of the emergent process. Thus, relentless efforts were made to not just seek for accurate representation of the phenomenon or the richness in the data but also to seek for unique attributes in the data so as to develop newly identified categories and subcategories.

Presentation of data

A total of 21 studies published between 1991 and 2018 formed the sample of analysis. Table 2 presents the 21 studies included in the analysis. The themes cut across but not limited to firm failure, learning from failure, coping with failure and emotional reactions towards failure. A number of study design including phenomenology, interpretative and case study were adopted to carry out the respective research. Additionally, data collection included interviews, field notes, field observations, documents and archival and internet sources. Interview was the most common means of data collection. However, several studies also had several means of data collection. Furthermore, the geographic setting for the studies cut across Europe, Africa, South America and North America.

Finally, studies consisted of 2 book chapter, 17 articles and 2 peer reviewed conference papers.

Findings

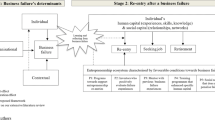

From the analysis of the articles, three overarching categories on how entrepreneurs manage business failure emerged. The experience and cost of failure – which identified the immediate effect from failure, the impact from failure – which identified the process taken after the occurrence of failure and the outcome of failure – which identified the actions taken after the entrepreneurs have made sense and recovered from failure. These categories were identified due to the constant statements that appeared consistently throughout the analyzed report where emphasis were placed on several aspects of the after effect of failure and how the several studies presented the experiences of the entrepreneurs studied. Their responses, emotions, and the actions they took after failure occurred. These led to the identification of constant statements, which were later grouped into subcategories and core categories for more meaningful abstraction.

The experience and cost of failure

Attribution and blame

The study shows that after the experience of failure, entrepreneurs attribute their failure to different factors. One main factor that failure was attached to the psychological and sociological cost discussed in previous research. In this light, it was the initial reactions as a result of failure. The entrepreneurs blamed failure on themselves and took personal responsibility for their failed firm. Specifically, on their inability, lack of effort, and from their own actions. As an entrepreneur from one of the reports mentioned, ‘The problems [contributing to the failure] were caused solely by bad decisions made by myself and [another entrepreneur], because quite simply we were the ones who made all the decisions as major owners of the firm’ (Mantere et al. 2013, p. 465). Additionally, the blame for business failure was also attributed to internal cost and unrealistic targets made by the entrepreneur. When attributing blame to failure, Mantere et al. (2013) showed that the entrepreneurs in their study only attributed blame to themselves and not the incompetence from their employees or personnel, however the employees attributed blame to the entrepreneurs and their incompetence to reasons why the venture failed. Their personnel expressed: ‘The CEO never saw to it that the different units would all row in the same direction”. “If the top management had been leading instead of envisioning, we wouldn’t have had eight firms within the firm.’ (p. 466).

Taking personal responsibilities for their actions and the firm failure, however, did not just help the entrepreneurs to reminisce over their failure but also help them make sense of what went wrong during the process of failure.

Stigmatization and social cost

One cost that entrepreneurs have to pay after failure is the cost of stigmatization. Although not all countries/regions stigmatize entrepreneurs who have failed, studies show that about 38% of 331 failed firm noted that they were stigmatized by their peer and the environment around them because of their failure. An entrepreneur who experienced failure noted that ‘failure led to exile and an abrupt end to one’s career’ (Cardon et al. 2011, P. 87). Additionally, entrepreneurs did not think that failing was an option because of how the society perceived failure. ‘There’s a huge stigma as well. I find that [long pause], failure’s not an option. You know. Nobody wants to talk about it. It’s the elephant in the room.’ (Byrne and Shepherd 2015, p. 375). Stigma from failed venture can lead to social isolation and the sense of loneness and anxiety.

The sense of stigmatization, however, does not just come from the external environment but can also emerge from the entrepreneurs themselves. Cope (2011), termed this as ‘self-imposed stigmatization’. Due to shame of failure, the entrepreneurs create their own social isolation because of the difficulty of accepting their failure. As an entrepreneur put it ‘there was nobody around me to tell me any different...nobody who could kind of say to me well look, you’re not a failure, you tried and you failed’ (Cope 2011, p. 611). Another entrepreneur also expressed how self-imposed stigmatization affected them after firm failure. ‘I was dumb and stupid because I didn’t know what I was doing…I wasn’t business savvy…and I didn’t have any business ownership or management experience’ (Singh et al. 2015 p. 156). Additionally, another entrepreneur expressed how he thinks he has let himself and his family down after the failure occurred. ‘I was letting people down, particularly my family…..I had convinced my wife that I could run the business successfully and that it was worth giving up a relatively secure job in the bank’ (Singh et al. 2015 p. 156). Interestingly, venture capitalist did not seem to stigmatize entrepreneurs who have failed (Cope et al. 2004).

Emotional and psychological experience

Firm failure is usually associated to emotional reactions and consequences. A significant aspect of the experience resulting immediately from failure is the psychological and emotional experience. Because entrepreneurs see the firm as their baby and/ or part of the family, they feel the same sense of negative emotional state such as grief as they would feel when they experience the loss of a family. For example, there was an expression by an entrepreneur comparing her loss to that of a family member. ‘It’s almost as if, it’s hard to describe it’s almost like, it’s almost like losing, I’ve not had any children myself but must be like losing a family or losing, because you don’t just loose, it’s your, life, you’re doing it every day so.’ (Byrne and Shepherd 2015 p. 382). They experience grief, despair, regret, anger, disappointment sadness and mostly negative emotions when failure occurs. The studies showed that the failed firm took an “emotional toll” on the entrepreneurs (Cope 2011 p. 610). For instance an entrepreneur expressed, ‘I think it is like grief….you have to go through all the screaming and wailing and crying and then you come out of that and feel you have dealt with it’ (Singh et al. 2007, p. 338, 341). Another example of such emotions was described by an entrepreneur who expressed guilt after the failure event occurred. He wishes that he would have averted failure if he had done something different. ‘Oh yeah, all the time. Just thinking, What if? What if we’d done this? What if we’d done that?’ (Byrne and Shepherd 2015 p. 381).

However, some entrepreneurs also expressed positive emotional state even after their firm have failed. They felt the sense of pride, hope, and confidence. For instance, reflecting on her failure event, this entrepreneur expresses that she got more insights from the failure event. ‘It’s made me, I don’t know, I think I’m a bit wiser, so I wouldn’t get myself into that situation again. I think it’s made me, probably more calmer in that I was so stressed for five years, well not five years, coming towards the end, probably the last two years.’ (Byrne and Shepherd 2015, p. 382).

Economical and financial cost

Apart from the emotional cost of failure, previous studies in qualitative research also record the financial and economic cost of failure. For instance, Cardon et al. (2011) show that 62 of 331 (19%) failed enterprises expressed some financial impact to the environment as a result of the failure occurrences. Additionally, report from Cope (2011), emphasized that all the entrepreneurs in their focus experienced financial loss which couldn’t be absorbed by some of the entrepreneurs who experienced loss. For instance, an entrepreneur admitted that he found it difficult to manage his depts after failure. ‘I couldn’t open anything, it cleaned me out basically…I had to go back to being an employee again’ (Cope 2011, P. 610).

Impact and transition from failure

Recovery: Coping and Sensemaking

While experiencing the cost of firm failure, entrepreneurs seek for means to recover. In doing so, they seek for strategies to cope with their failures and make sense of the situations that led to such failures. The studies show that the recovery process from failure is mostly related to emotions and emotional reactions. Several factors were shown to be important when entrepreneurs cope and make sense of their failure. Entrepreneurs tried to cope with their failure by reflecting retrospectively on such failure. Some of them did that by asking themselves several questions such as ‘Did we make the right decisions? Did we pick the right strategy? Did we hire the right people? Did we make decisions in a timely manner? Did we treat our people fairly? You know, you go through all those sorts of thing’ (Cope 2011, P. 613). Additionally, they also focused on doing other things at the recovering stage for instance an entrepreneur expressed, ‘I needed that, I needed just to heal and get over it because it was very hurtful’ (Cope 2011, P. 613). Furthermore, the research also highlights the importance of networks and the presence of family members when recovering and coping with failure.

Furthermore, findings show that the entrepreneurs who experienced higher sense of negative emotions made more sense of their failure, while those who experienced lower state of emotions towards their failure had little sensemaking about their experiences from the failure (Byrne and Shepherd 2015). For some entrepreneurs, it took less than two months to recover and made sense from their failed experience and for others it took longer than two years (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2018). However, entrepreneurs took out time to reflect and recover from their failed venture. Additionally, positive emotions from failed venture also allowed the entrepreneurs to make use of cognitive strategies when making sense of their failed venture, where they were able to make sense of what went wrong by relating and comparing business failures to past experiences (Byrne and Shepherd 2015).

Learning from failure

After the sensemaking and recovery process, entrepreneurs mentioned that they have learnt from their past experience through reflections and sensemaking. Additionally, the emotional cost also helped them to learn from their past experiences. They also expressed the need to not repeat the same mistake and not take similar decisions that led to their initial firm failure when they engage in new entrepreneurial endeavors. Amankwah-Amoah et al. (2018) found that the grieving period for entrepreneurs who have experienced failure was the beginning of their learning process. The entrepreneurs emphasized that grieve paved the way for them to evaluate the causes for their previous failure. The findings also expressed further how negative emotions can yield positive outcomes because it gives the entrepreneurs enough time to reflect and articulate the causes of failure and find the opportunity to make changes with future venture engagements. They were able to learn more about their venture and why it failed, their networks and external relationships and also how to better manage their firm in the future (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2018; Singh et al. 2007; Cope 2011; Walsh 2017).

Apart from learning and reflecting on what did not work in the firm that led to failure, the findings also show that entrepreneurs learn more about themselves during the reflection and sensemaking stage (Cope 2011). When reflecting on his experience an entrepreneur expressed how he has become more resilient because of what he has learnt from his business failure and the processed he went through during that period (Cope 2011, P.616). Additionally, another entrepreneur expressed ‘I’ve never been the same since…I’ve never had the same total confidence as I had in those days, which has been good and bad’ (Cope 2011. P. 616). Categorically, entrepreneurs use the information of what they have learned during the coping and sensemaking phase to become self-aware of their weaknesses and strengths. Besides becoming aware of their strengths and weaknesses, the entrepreneurs also brought with them their prior skills and knowledge which expedited their learning process.

Outcome of failure

Competence development

Studies show that even though the entrepreneurs failed in their venture attempt, they were able to gain new knowledge and skills from engaging in the venture. The entrepreneurs made use of these competence during the process of failure to mitigate the effect from the event (Minello et al. 2014). In addition, learning from this failure also made them more aware of how much they developed during their initial venture engagement. For instance, findings highlight that their prior experience, expertise and network gained from the initial failed firm motivated them to re-enter the venture in which they previously failed from (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2018).

New opportunity identification

Learning from failure and gaining new insights, the studies show that the entrepreneurs moved ahead to seek for other business opportunities using the knowledge and networks that they already established. This provided the entrepreneurs with the ability to exploit new business opportunities (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2018). The findings show that entrepreneurs moved ahead to seek and recognize opportunities, seen new niche and fields where they re-established and started other firms (Atsan 2016).

Additionally, after the event of failure, venture capitalist was also interested in investing in entrepreneurs who have previously failed, since recognizing new business opportunities were more important for the venture capitalist than previous failures of entrepreneurs. For instance, a venture capital in the UK expressed that it ‘depends entirely on the concept’ of the new business opportunity (P. 158) and not on the fact that the entrepreneur has previously failed (Cope et al. 2004). Another venture capitalist also stated that since failure is an experience, they will support entrepreneurs seeking for new opportunities rather than new and novice entrepreneurs. She states ‘I would prefer to back a failed entrepreneur, subject to seeing what the failure was. .. than a new starter’ (Cope et al. 2004: P. 161).

New venture engagement

Most entrepreneurs who experience failure and learned from it, usually use their failed experience as an opportunity to engage in new venture. Findings highlight that the process in founding a new business venture is one means entrepreneurs use to recover from their previous failed experiences (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2018; Walsh 2017). Walsh (2017) highlight that in order to effectively re-enter and start a new venture, entrepreneurs must learn to detach themselves from the failed firm, acknowledge that the firm has failed, and deflect from stigmatization (P.103). Additionally, entrepreneurs also express that their previous failed experiences help them to direct their future business and career path and the decisions leading to it (Dias and Teixeira 2017).

Discussion and conclusion

Based on the meta- interpretation (meta- ethnography and grounded formal theory), previously identified components of what happens after failure and different means in which entrepreneurs manage failure were substantiated. Although some of the reports took on greater significance and relationships among concepts were clarified, the present study contributes by consolidating different conceptual components from several qualitative studies and bringing these broad spectrum of data together so as to provide an overview of the phenomenon studied. Although evolving, entrepreneurial and firm failure should not be considered as a new concept but rather a stream of research that helps understand more about the entrepreneurial and firm process. This understanding has therefore presented the distinctions between business failure and exit (e.g., DeTienne 2010).

The nature of firm failure can be a psychological, social and economic rollercoaster for entrepreneurs who experience failure such as bankruptcy, discontinuation or any type of involuntary exit (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2018; Cardon et al. 2011; Cope et al. 2004; Cope 2011; Singh et al. 2007). This is due to the fact that entrepreneurs liking their venture to family members or loved ones. Thus, leading them to devote economic (finance) and psychological (emotions) investment into their venture as a result of the significance they attach to these ventures. When the realization that failure has occurred, the entrepreneurs experience several costs. They experience similar emotional process as either denying failure by delaying it for so long before finally, accepting it (Shepherd 2003; Shepherd et al. 2009) or accept the failure right away. Regardless, these entrepreneurs still experience some sought of negative emotions such as grief and regret. The findings from the synthesized reports demonstrates that grief is one emotion that most entrepreneurs go through when their firm fails. This leads them to reminisce over the failed venture and mourn their venture as though they lost a close relative or friend. Additionally, during the process of grief, they tend to not only disconnect themselves from those around them (such as their networks) but also attribute blame to themselves for failing and hoped the actions and decisions leading to failure were different (Mantere et al. 2013). Contrary to the former, some entrepreneurs express positive emotions even after the failure. This positive emotion serves as beneficial when getting over the emotional loss of the venture and aid quick recovery (Shepherd 2003; Singh et al. 2007).

Leading to the experience and cost of failure, entrepreneurs also experience impact from these failures where they have to transition through recovering from the said failure, coping and making sense from such failure and eventually learning from the failure. The findings show that entrepreneurs who experience more emotions during the failure phase recover quicker from the failure (Byrne and Shepherd 2015). Notwithstanding, after experiencing failure, entrepreneurs find different means to recover from it. More specifically, they cope by reminiscing and making logical reasons why the venture failed, thereby making sense of such failure (Singh et al. 2007). With logical explanations and reasons for the circumstances that led to failure, the entrepreneurs are able to learn from their failure. They recall on what, how and why they failed. This conscious action and sensemaking from their firm failure, generates more knowledge on future actions to take.

Results from the synthesis highlight that entrepreneurs yield positive outcomes when they are able to make sense of their failure and learn from it. They are more equipped with more knowledge and experience from previous engagement, where they are able to make better decisions for future actions and engagements. The results show that with this knowledge and experience, entrepreneurs gain more competence from their previous engagement to apply to their prospective engagement. Additionally, the entrepreneurs use their previous and new acquired knowledge after failure to either seek for new venture opportunities or start new ventures in the same line of business.

The study first contributes to the research on failure by highlighting the state of art of research on failure by presenting a figure on the process of how entrepreneurs manage firm failure. Figure 1 highlights that entrepreneurs go between the experience, cost and the impact of failure and the transition phase in order for them to not just grief the process of failure but at the same time recover and make sense from the failure. Constant iteration between experiencing the failure and the impact of the failure aid the entrepreneurs into taking further actions towards new opportunity identification and new venture creation.

The findings provide insights on how entrepreneurs manage failure by focusing on what happens after entrepreneurial ventures have failed. Three overarching themes evolved from a meta interpretations (a combination of meta- ethnography and grounded formal theory): The experience and cost of failure; The impact and transition from failure and; The outcome of failure. Within these themes, several aspects for future theoretical contributions were identified.

First, the findings recall how (positive and negative) emotions are important for coping and recovering through failure. Although the records on the positive outcomes from positive emotions were less frequent/studied as compared to the outcomes of the experience of negative emotions (Shepherd and Cardon 2009; Byrne and Shepherd 2015), future research can also benefit more from how positive emotions can either expedite or hinder the recovery process from failure and if positive emotions will always yield positive outcomes after the experience from failure.

Second, the findings from the synthesis emphasize that after the experience and learning from failure, entrepreneurs either seek for new business opportunities or engage in similar business ventures to the failed venture. Findings however, did not highlight if some of these entrepreneurs gain paid employment after their failure rather than starting new ventures or how many of those who have failed seek gained employment. Future research can look into those entrepreneurs who seek gained employment instead of starting new ventures so as to highlight their motivations, reasons and consequences of such actions.

Third, although the findings highlight psychological, physiological, social and financial cost of failure, limited research still remains on the physiological consequences on failure. Such as how and to what extent firm failure affects the health and standard of living of these entrepreneurs who have experienced failure and how they manage such influences. More knowledge from future research would provide more insights into answering these questions.

Finally, the current study presents a model that discusses how entrepreneurs experience and manage failure. Starting from the experience and cost of failure, to the impact from failure and then the outcome of failure. More knowledge on the dynamic process of the experiences of failure may provide more insight on the means entrepreneurs take for future venture engagement or disengagement.

The current research responds to an ongoing discussion on how entrepreneurship research can apply various ways in which qualitative research can aid in extending and providing deeper understanding in the research field (Suddaby et al. 2015). Therefore, the originality of applying the methodological approach of a meta-interpretation in entreprneurship research welcome reactions either to challenge or object.

Limitations and future research

The nature of the methodology, however, is not without limitations. The qualitative synthesis may raise practical, epistemological and methodological questions. The goal for conducting this kind of research however is to bring together several findings on a particular topic, theme, or subject through the re-interpretation of published findings rather than primary data. Thus, allowing the results from the synthesis to go beyond the description and presentation of results in literature review and involve conceptual development, which is distinct from the quantitative meta- analysis. Given that the current study adopted two methods for synthesizing qualitative research – meta-ethnography and the formal grounded theory, − future research can therefore explore other methods to identify if new or different categories would evolve or to see if the current outcome of the synthesis is influenced by the specific method adopted.

Further, the findings were only restricted to the results from the synthesized qualitative results therefore omitting results from quantitative research. However, this study aimed to seek deeper knowledge and understanding on the phenomenon concerning how entrepreneurs manage failure and not to seek for numerical or quantitative synthesis that includes causations and effects. Although there are several qualitative, quantitative and conceptual papers on entrepreneurial and business failure, the present qualitative synthesis highlights some remarkable similarities in the several studies analyzed which, identified different reoccurring themes that arose in entrepreneurial failure management (for instance, themes such grief, regret, coping, and entrepreneurial learning). This finding does not just show some repetition in the synthesized studies but also to provide avenue on the extensions of the above themes in future research. Based on these findings, future research can therefore explore more on how entrepreneurs engage in new venture opportunities after the occurrence of failure.

References

Amankwah-Amoah, J., Boso, N., & Antwi-Agyei, I. (2018). The effects of business failure experience on successive entrepreneurial engagements: An evolutionary phase model. Group & Organization Management, 43(4), 648–682.

Atkins S, S Lewin, H Smith, M Engel, A Fretheim and J. Volmin 2008. “Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt”. BMC Med Res Methodology.

Atsan, N. (2016). Failure experiences of entrepreneurs: Causes and learning outcomes. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 435–442.

Bauer, A. K. (2016). Learning from business failure–does restarting affect the business model design. Junior Management Science, 1(2), 32–60.

Byrne, O., & Shepherd, D. A. (2015). Different strokes for different folks: Entrepreneurial narratives of emotion, cognition, and making sense of business failure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(2), 375–405.

Campbell R, Pandora P, Myfanwy M, Gavin D.W, Nicky B, Pill R, Lucy Y, Catherine P, and Donovan J. 2012. “Evaluating meta ethnography: Systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research.” Health Technology Assessment.

Cannon, M. D., & Edmondson, A. M. (2001). Confronting failure: Antecedents and consequences of shared beliefs about failure in organizational work groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(2), 161–177.

Cardon, M. S., Stevens, C. E., & Potter, D. R. (2011). Misfortunes or mistakes? Cultural sensemaking or entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 79–92.

Cope, J. (2011). Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 604–623.

Cope, J., Cave, F., & Eccles, S. (2004). Attitudes of venture capital investors to entrepreneurs with previous business failure. Venture Capital”: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 6(2/3), 147–172.

Corner, P. D., Singh, S., & Pavlovich, K. (2017). Entrepreneurial resilience and venture failure. International Small Business Journal, 35(6), 687–708.

Cotterill, K. 2011. “Entrepreneurs' response to failure in early stage technology ventures: A comparative study”. In first international Technology Management Conference (pp. 29-39). IEEE.

DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215.

Dias, A., & Teixeira, A. A. (2017). The anatomy of business failure: A qualitative account of its implications for future business success. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 26(1), 2–20.

Finfgeld, D. L. (1999). Courage as a process of pushing beyond the struggle. Qualitative Health Research.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies of qualitative research. London: Wiedenfeld and Nicholson.

Hayward, M. L., Forster, W. R., Sarasvathy, S. D., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). Beyond hubris: How highly confident entrepreneurs rebound to venture again. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 569–578.

Headd, B. (2003). Redefining business success: Distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Business Economics, 21(1), 51–61.

Huovinen, J., & Tihula, S. (2008). Entrepreneurial learning in the context of portfolio entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 14(3), 155–171.

Jenkins, A., Wiklund, J., & Brundin, E. (2014). Individual responses to firm failure: Appraisals, grief, and the influence of prior failure experience. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 17–33.

Kearney, M. H. (2001). Enduring love: A grounded formal theory of women's experience of domestic violence. Research in Nursing & Health, 24(4), 270–282.

Larson, C. M., & Clute, R. C. (1979). The failure syndrome. American Journal of Small Business, 4(2), 35–43.

Mandl, C., Berger, E. S., & Kuckertz, A. (2016). Do you plead guilty? Exploring entrepreneurs’ sensemaking-behavior link after business failure. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 5(1), 9–13.

Mantere, S., Aula, P., Schildt, H., & Vaara, E. (2013). Narrative attributions of entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 459–473.

McGrath, R. G. (1999). Falling forward: Real options reasoning and entrepreneurial failure. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 13–30.

Minello, I. F., Alves Scherer L and da Costa Alves L.. 2014. “Entrepreneurial competencies and business failure”. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 18.

Minniti, M., & Bygrave, W. (2001). A dynamic model of entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 25(3), 5–16.

Mitchell, R., Mitchell, J., & Smith, J. (2004). Failing to succeed: New venture failure as a moderator of startup experience and startup expertise. In W. D. Bygrave (Ed.), Frontiers of entrepreneurship research. Wellesley: MA: Babson College.

Nikolić, N., Jovanović, I., Nikolić, Đ., Mihajlović, I., & Schulte, P. (2019). Investigation of the factors influencing SME failure as a function of its prevention and fast recovery after failure. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 9(3).

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesising qualitative studies. London: Sage.

Nummela, N., Saarenketo, S., & Loane, S. (2016). The dynamics of failure in international new ventures: A case study of Finnish and Irish software companies. International Small Business Journal, 34(1), 51–69.

Politis, D., & Gabrielsson, J. (2009). Entrepreneurs' attitudes towards failure: An experiential learning approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 5(4), 364–338.

Pretorius, M. (2008). Critical variables of business failure: A review and classification framework. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 11(4), 408–430.

Shepherd, D. A. (2009). Grief recovery from the loss of a family business: A multi- and meso-level study. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(1), 81–97.

Shepherd, D. A., & Cardon, M. S. (2009). Negative emotional reactions to project failure and the self-compassion to learn from the experience. Journal of Management Studies, 46, 923–949.

Shepherd, D. A., & Haynie, J. M. (2011). Venture failure, stigma, and impression management: A self-verification, self-determination view. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 5(2), 178–197.

Shepherd, D. A., Douglas, E. J., & Shanley, M. (2000). New venture survival: Ignorance, external shocks, and risk reduction strategies. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 393–410.

Shepherd, D. A., Wiklund, J., & Haynie, J. M. (2009). Moving forward: Balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(2), 134–148.

Shepherd, D. A., Williams, T., Wolfe, M., & Patzelt, H. (2016). Learning from entrepreneurial failure: Emotions, cognitions, and behaviors. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Singh, S., Corner, P., & Pavlovich, K. (2007). Coping with entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Management & Organization, 13, 331–344.

Singh, S., Corner, P. D., & Pavlovich, K. (2015). Failed, not finished: A narrative approach to understanding venture failure stigmatization. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 150–166.

Singh, S., Corner, P. D., & Pavlovich, K. (2016). Spirituality and entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 13(1), 24–49.

Sitkin, S. B. (1992). Learning through failure: The strategy of small losses. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Suddaby, R., Bruton, G. D., & Si, S. X. (2015). Entrepreneurship through a qualitative lens: Insights on the con-struction and/or discovery of entrepreneurial opportunity. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 1–10.

Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., Wright, M., & Flores, M. (2010). The nature of entrepreneurial experience, business failure and comparative optimism. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 541–555.

Ucbasaran, D., Shepherd, D., Lockett, A., & Lyon, S. J. (2013). Life after business failure: The process and consequences of business failure for entrepreneurs. Journal of Management, 39(1), 163–202.

Walsh, G. S. (2017). Re-entry following firm failure: Nascent technology entrepreneurs’ tactics for avoiding and overcoming stigma. In Technology-based nascent entrepreneurship (pp. 95–117). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Walsh, G. S., and Cunningham J. A. 2017. Regenerative failure and attribution. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research.

Yamakawa, Y., & Cardon, M. S. (2015). Causal ascriptions and perceived learning from entrepreneurial failure. Small Business Economics, 44(4), 797–820.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Mälardalen University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Omorede, A. Managing crisis: a qualitative lens on the aftermath of entrepreneurial failure. Int Entrep Manag J 17, 1441–1468 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00655-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00655-0