Abstract

Advancing age is associated with chronic diseases which are the largest cause of death and disability in developed countries. With increasing life expectancy and an ageing population, there is a need to conduct trials to extend healthy ageing, including targeting biological ageing processes, and prevent ageing-related diseases. The main objectives of the study are as follows: (i) to review outcome measures utilised in healthy ageing trials focusing on pharmacological therapies, nutritional supplements and medical devices; (ii) to summarise the views of key stakeholders on outcome selection for healthy ageing trials. An analysis of records from the Clinicaltrials.gov database pertaining to healthy ageing trials from inception to May 2022 was conducted. In addition, the findings of a workshop attended by key stakeholders at the 2022 annual UKSPINE conference were qualitatively analysed. Substantial heterogeneity was found in the interventions evaluated and the outcomes utilised by the included studies. Recruitment of participants with diverse backgrounds and the confounding effects of multi-morbidity in older adults were identified as the main challenges of measuring outcomes in healthy ageing trials by the workshop participants. The development of a core outcome set for healthy ageing trials can aid comparability across interventions and within different settings. The workshop provided an important platform to garner a range of perspectives on the challenges with measuring outcomes in this setting. It is critical to initiate such discussions to progress this field and provide practical answers to how healthy ageing trials are designed and structured in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population ageing is an important public health challenge [1]. Globally, it is estimated by year 2050 there will be 392 million people aged 80 years or above [2]. There are serious health implications associated with this projected demographic change in the next few decades [3]. Ageing is associated with chronic diseases which are the largest cause of death and disability in developed countries [4, 5] as well as resulting in reduced quality of life of individuals [6]. For instance, ageing is considered as a primary risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease which are associated with disability and reduced functionality in daily activities [7]. Moreover, there are serious issues of health inequalities amongst older adults which are mainly attributed to ethnicity, gender and socio-economic position [8,9,10].

Current research pertaining to ageing mainly entails exploring the biological mechanisms of ageing to better understand the factors associated with age-related diseases to improve health amongst older age groups [11, 12]. The increased knowledge of the molecular mechanisms associated with ageing such as chronic inflammation, DNA damage, dysfunctional mitochondria and increased senescent cell load has led to testing various therapeutic interventions [12, 13]. These interventions primarily aim to slow the ageing process and increase health span by preventing the development of chronic disease and disability [12].

There are various pharmacological interventions that have been indicated by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Interventions Testing Program (ITP) in pre-clinical trials which target disease prevention and life span extension in rodents [14,15,16]. At present there is no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug for an ageing-related indication [14]. Certain drugs such as metformin and rapamycin, which are already in clinical use, are being tested in human trials to target the ageing process to prevent development of chronic diseases [14]. The literature suggests that there are unique challenges associated with conducting such healthy ageing trials in human subjects [17,18,19,20,21]. Some of these challenges include lack of a consensus regarding reliable ageing biomarkers, inclusion of mainly healthy subjects in anti-ageing trials (due to multi-morbidities and medication being an exclusion criteria) and issues of participant diversity which weakens the generalisability of findings [17,18,19,20,21].

Moreover, the randomised controlled trials conducted have utilised a diverse range of outcome measures to determine the effectiveness of interventions, suggesting a lack of a standardised approach to measure outcomes pertaining to healthy ageing [22,23,24]. This makes evidence synthesis and comparisons of the effectiveness of various interventions difficult [22,23,24].

These issues could be addressed through the development and utilisation of a core outcome set—‘an agreed standardised set of outcomes that should be measured and reported, as a minimum, in all clinical trials in a specific area’ [25]. This can be achieved through multiple stakeholder (industry, clinicians, patients and investors) input. It is important for these key stakeholders to discuss and agree on ‘what to measure’ and ‘how to measure’ in the context of healthy ageing trials.

UK SPINE is a national knowledge exchange network composed of higher educational institutions, industry and the charitable sector which aims to promote research in healthy ageing [26]. This study is part of the UK SPINE initiative. The objectives of the study were to (i) review the outcome measures utilised in healthy ageing trials specifically focusing on medicinal drugs, dietary supplements and devices; (ii) to summarise the views of key stakeholders (industry, clinicians, patients and investors) on the outcomes that they considered most important when conducting healthy ageing trials and how these can be measured as a first step to inform future core outcome set development.

Methods

This mixed methods study comprised of an analysis of the records of healthy ageing trials registered on the Clinicaltrials.gov database and qualitative data collected during a workshop with key stakeholders who attended the UK SPINE annual conference 2022 [26].

Review of healthy ageing trials

Search strategy and selection criteria

The ClinicalTrials.gov database was searched for records of relevant studies. The database is designed to provide easy access to summary information on publicly and privately funded clinical trials and observational studies [27]. The terms ‘healthy ageing’, ‘ageing well’, ‘ageing’, ‘anti-aging’ and ‘aging process’ were searched from inception to May 2022. Studies were eligible if identified as a healthy ageing trial of pharmacological therapies, dietary supplements or medical devices. Studies were excluded if they included interventions other than pharmacological therapies, supplements and medical devices.

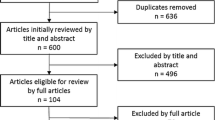

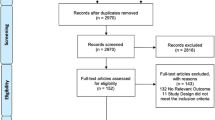

Data screening

The retrieved records were downloaded in an Extensible Markup Language (XML) file. Two independent authors (MS and OLA) systematically screened for eligible studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and a third author (MC) was involved when necessary.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction occurred after the final selection of included studies. MS and OLA independently extracted details on clinical condition, type of intervention (drugs or devices), outcomes assessed, main outcome measures, interventional model, age and gender of participants, inclusion criteria of study, study funding and study location.

Stakeholder workshop

Aim of the workshop

The UK SPINE annual conference 2022 was designed to explore the scientific research behind healthy ageing, including showcasing some of the research UK SPINE has supported, as well as providing a platform for discussion of the broader context for translational research to treat age-related conditions [26]. The conference therefore provided the ideal forum to engage with key stakeholders that possess the knowledge and experiences relevant to the study. A workshop was organised to explore and capture diverse perspectives from participants on several topics including the role of stakeholder groups in conducting healthy ageing trials and outcomes selection; outcomes considered most important in healthy ageing trials; challenges associated with measuring outcomes; and strategies for consensus and development of a core outcome set (COS) for healthy ageing trials testing drugs, supplements and devices interventions.

Recruitment of participants for the workshop and format of the workshop

Individuals registered for the UKSPINE annual conference were invited via email to participate in the workshop. The participants were provided information sheets and given the opportunity to ask questions. Written consent was taken prior to starting the workshop by researchers (MS and EM) who facilitated the workshop.

A summary of the findings of the Clinicaltrials.gov analysis was presented to the workshop participants. This was followed by interactive discussions using a topic guide which had domains pertaining to the challenges, barriers, the need to develop a COS, strategies for development of core outcome set and the role of the main stakeholders for measuring outcomes whilst testing drugs and devices interventions in healthy ageing trials (Table 1).

Data collection and analysis

Flipcharts were utilised to make note of responses of participants and highlight key points as the various themes were discussed amongst the key stakeholders. Personal reflection notes were also taken during the discussions to aid reflection and inform the analysis of the qualitative data. The workshop ran for 45 min as a breakout session within the conference.

The data was analysed using thematic analysis [28]. The data was analysed by MS and EM who interpreted explored and reported patterns and clusters of meaning within the given data [29]. This technique was selected as it allows flexibility as it is not tied to any particular discipline or set of theoretical constructs [29]. A Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis (CAQDAS) package (NVivo 12 for Windows) was utilised for this process. The results of the study were reported in accordance with ‘Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research’ (COREQ) [30] and ‘Standards for reporting qualitative research’ (SRQR) [31] guidelines to ensure good qualitative research practice.

Results

Analysis of healthy ageing trials

The search on the ClinicalTrials.gov database yielded 342 studies. Of these, 36 primarily focused on testing drugs, supplements or devices in healthy ageing trials and were included in the review.

Demographic details and study characteristics

A majority of the studies (n = 31; 86%) included were interventional studies (Table 3) and just over half (n = 20, 55%) were from the USA (Table 2). A wide range of interventional models were utilised ranging from parallel assignment, cross over assignment to observational (Table 3). The age of the participants ranged from 13 to 100 years in the included studies (Table 3) and most included male and female participants (Table 3). Funding of 23 was generated by academia, followed by pharmaceutical industry (n = 5), medical manufacturing (n = 5), healthcare institution (n = 1) and multi-lateral network (pharmaceuticals, academia and non-profit organisations) (n = 2) as demonstrated in Table 2.

Conditions considered in the studies

The prevention of a range of diseases was the primary goal of the studies. Half of the studies (50%) investigated general ‘healthy ageing’ whilst others focused on prevention of specific disease conditions such as cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, hearing loss and multiple disease conditions (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Interventions

There was marked heterogeneity in the interventions evaluated in the studies as shown in Table 2. Pharmacological agents investigated included vitamin D3, omega 3 fatty acids, phosphate, creatine monohydrate, maltodextrin powder etc. (Table 2). Devices investigated included Tele-Tai Chi, non-invasive brain stimulation and in-home resonance-based electromagnetic field protection device (Table 2).

Outcome measures utilised in studies

In total, 15 studies included cognitive outcome measures such as working memory task and performance (Table 2). Other outcome measures included diagnostic (biomarkers and lab tests) (n = 12), physiological (pupil size, muscle thickness, physical activity etc.) (n = 12), biochemical (blood oxygen levels, plasma nitrates, hormone levels etc.) (n = 5), mental health (e.g. Beck’s inventory) (n = 1) and patient-reported outcome measure (n = 1) as depicted in Table 2.

Stakeholder workshop

Demographic details and themes identified from the workshop

There were a total of 10 participants that attended the workshop. The workshop participants had diverse professional backgrounds including academics (n = 2), investors (n = 2), representatives of pharmaceutical industry (n = 2), clinician (n = 1), patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) manager (n = 1), patient (n = 1) and policy maker (n = 1). Their experience of healthy ageing trials ranged from 1 to 5 years. The following themes were identified (Table 4):

-

i)

Role of stakeholder groups

A central finding of the workshop was the acknowledgement that whilst academia and the pharmaceutical industry commonly take the lead in healthy ageing trials, a larger number of stakeholders should be involved. A PPIE manager elaborated about the significance of academics and pharmaceutical industry professionals initiating healthy ageing research:

‘Academia and pharmaceuticals have the required knowledge and skills to conduct research. Not everyone can understand the biological process involved in ageing and how it can be intervened. They should lead firstly and then engage and involve other key stakeholders’

An academic whilst emphasising the need to adopt a collaborative approach for designing health ageing trials commented:

‘I think it should be a collaborative approach, the academia needs to generate the evidence which can be shared with the key stakeholders such as industry, policy makers and even patients and their engagement officers while designing aging trials considering the multi-morbidities in the elderly’

-

ii)

Important outcomes to consider in trials

Various outcomes were identified as important whilst testing drugs and devices in healthy ageing trials. These included mobility, autonomy, quality of life measures, diagnostic (lab tests and biomarkers) and assessment of physiological indicators. It was further emphasised by the participants that it was important to develop consensus amongst the key stakeholders whilst selecting the outcomes to fully assess the interventions and its effects on the life span and health span of patients.

Similarly, a policy maker highlighted the patients’ perspectives whilst considering outcomes:

‘In my opinion mobility, autonomy and quality of life measures are extremely important to consider especially from the perspective of patients’

-

iii)

Challenges associated with measuring outcomes

Recruitment of participants and the confounding effects of multi-morbidity in older adults were identified as key challenge of measuring outcomes in healthy ageing trials. In particular, the recruitment of cohorts which are representative of the general population, including (but not limited to) ethnic minority groups at greater risk of age-related diseases. Statistical powering of studies was a major hurdle to address. Retention of participants and providing ongoing support were also critical factors for consideration as suggested by participants.

A pharmaceutical industry representative elaborated on the challenges associated with measuring outcomes in healthy ageing trials:

‘As elderly patients generally have multiple morbidities, polypharmacy and associated side effects of existing drug prescriptions can influence the outcomes that are assessed of a particular intervention. The findings can be biased and not truly representative of the effectiveness of the drug. It is worth considering the complexity of chronic disease and its treatment among the elderly patients’

A senior academic mentioned the challenge of patient recruitment and retention:

‘Most trials exclude elderly patients with multiple diseases, it is important to recruit a representable sample and make the findings generalizable… another concern I would say is that such trials are lengthy and recruiting and retaining elderly population in such trials can be challenging. You can’t overlook dropouts as well; this also has to be taken into consideration’

-

iv)

Suggested strategies for establishing core outcomes

Different strategies were suggested for establishing a core outcome set for healthy ageing trials. It was suggested that the evidence generated from previous published literature can serve as an important starting point to build consensus amongst the key stakeholders. It was further emphasised that academics should take a lead in such discussions. An academic commented:

‘The subject matter experts such as researchers and academics who have the relevant and substantial experience in healthy ageing trials should lead the discussions, but future design should be informed by wide consultation, particularly representative of the target population for healthy ageing trials, this I think will be the right approach’

The significance of a diverse population in consensus building exercise was highlighted by the PPIE manager who suggested:

‘Diverse representation from population groups in terms of gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic backgrounds should be involved and engaged in consensus building exercise’

A pharmaceutical representative whilst discussing further refinement and development of mutually agreed COS suggested:

‘I think at later stages of development focus group discussions and Delphi approaches are very useful methods which can be utilized for refinement and consensus of mutually-agreed core outcomes set’

Discussion

Key findings

The main findings of the review highlight that there are a range of measures that are being utilised in healthy ageing trials testing pharmacological therapies, supplements and medical devices. However, even when addressing a similar concept there is no standardised approach to assessment of these outcomes. A range of outcome measures were considered important by workshop participants for healthy ageing trials which included mobility, autonomy, quality of life measures, diagnostic (lab tests and biomarkers) and assessment of physiological indicators. It was discussed that recruitment of participants and the confounding effects of multi-morbidity in older adults act as key challenges of measuring outcomes in healthy ageing trials. The analysis of data from the workshop highlighted the potential value of reaching consensus on a COS that could be assessed in future healthy ageing trials. Different strategies were suggested for development of COS which included gathering information from previous published literature, active involvement of key stakeholders in discussing key findings and conducting focus group discussion and use of Delphi methodology for further refinement and mutual agreement on consensus of COS.

Comparison of study findings with existing evidence

Presently there is a dearth of biomarker and resource development to investigate novel biomarkers and therapeutic interventions [32]. There is also a need to validate the existing biomarkers that are currently being utilised including composites of different markers for utilisation in clinical trials related to ageing [13, 32]. Moreover, the literature suggests that outcomes associated with healthy ageing should be multidimensional positive health outcomes and comprehensively measure the functionality of individuals and adaption to environmental challenges in context with their social, mental and physical well-being [33]. Similarly, the World Health Organisation also strongly advocates health as a holistic concept inclusive of the essential domains of social, physical and mental wellbeing [33]. The studies included in the review utilised some of the outcomes measures based on these broader domains to assess the effectiveness of interventions (drugs or devices) in healthy ageing and other age-related diseases but there was marked heterogeneity in measures used in these trials. The diverse range of outcomes, criteria and scales for measurement of effectiveness of interventions utilised in the studies suggest a lack of a standardised approach to measure outcomes pertaining to healthy ageing. This makes comparisons of the effectiveness of interventions difficult. It can be further argued that even within individual trials focusing on limited outcome measures may not fully capture the benefits of the drug or device intervention with regard to its contribution both towards the health span and life span of patients [34,35,36]. Importantly, it is increasingly recognised over the last few decades that life span and health span are different attributes associated with health outcomes of interventions and cannot be interchangeably used to interpret study findings [35].

The participants recruited in the studies included in the review included healthy individuals with a certain level of physiological functionality and neurocognitive abilities. It can be argued that inclusion of only healthy older adults and excluding individuals with co-morbidities and multiple drug prescriptions can influence the effects of interventions targeting ageing making them less relevant to the older population [13].

The findings of the review and workshop highlight the significance of development of a core outcome set for healthy ageing trials. This is substantiated by the fact that there is increased emphasis in recent literature on utilisation of common data elements and core outcome measures to address the issues of interpretation, generalisation and implementation of the research findings of clinical trials [37]. Moreover, the funding bodies and regulatory agencies also strongly advocate the standardisation of reporting and conducting clinical trials [38]. The workshop participants (academics, clinicians, patient public representative, industry representatives and patient) recommended the need for multiple stakeholders to collaborate and design healthy ageing trials and develop core outcome set with special consideration of complications of co-morbidities amongst older patients. This finding is supported by evidence which describes the key challenges associated with measuring healthy ageing suggesting a multi-sectoral approach whilst designing such trials [39, 40]. The findings of this study suggest that one of the main challenges associated with measuring outcomes in healthy ageing trials is the recruitment of participants who are truly representative of the general population. Various studies conducted in developed countries support these findings and highlight the complexities of diverse socio-demographic characteristics, multi-morbidities and the prevailing health inequalities amongst the ageing population [39, 41, 42]. Hence, it is equally important to include individuals from diverse backgrounds in COS development as emphasised in the workshop by the key stakeholders.

Limitations of the study

The limitations of the review include that there are certain limitations associated with the search engine clinicaltrials.org such as the search engine not having all information on studies and records can be changed by a responsible party. Nevertheless, it is very unlikely that the researchers would change the intervention (drugs or devices) and the set outcome measures once the study has been initiated. The review only focused on pharmacological therapies, supplements and medical devices and did not include other interventions such as behavioural, dietary or social interventions. Another limitation of the study can be that in-depth qualitative interviews were not conducted to capture views of key stakeholders. This methodology can yield more information about the perceptions of the key stakeholders and offer a more robust analysis opportunity. However, the workshop was designed to answer focused themes/questions and provided efficient opportunity to extract important information from a wide range of key stakeholders which included academics, clinicians, patient public involvement manager, industry representative and patient. The workshop was conducted as part of conference breakout, which limited participation to conference attendees. Findings from the workshop were very important, and including a diverse range of relevant stakeholders however it would have been useful to include a greater number of participants to corroborate these views.

Future recommendations

The following key recommendations are suggested based on the findings of the study:

• There is a need for core outcome set development for healthy ageing trials (for comparability across interventions and within different settings to better interpret and increase the generalisability of the findings of the studies) by active collaboration and evidence-based consensus with key stakeholders in accordance with the COMET initiative [25] |

• The multi-morbidities associated chronic health complications, ongoing treatments associated with ageing should be carefully considered whilst testing pharmacological therapies, supplements and medical device interventions |

• Future studies should aim to recruit participants from diverse backgrounds to increase the generalisability of findings |

Conclusion

A range of outcome measures have been used to support endpoint assessment in healthy ageing trials. The diverse range of outcomes, criteria and scales for measurement of effectiveness of interventions utilised in these studies suggest a lack of a standardised approach to measure outcomes pertaining to healthy ageing. This makes comparisons of the effectiveness of interventions difficult. The workshop provided an important platform to garner a range of perspectives on the considerations around the use of outcome measures in clinical trials for healthy ageing. It is critical that such discussions occur to progress this field and provide practical answers to how trials of this type are designed and structured.

References

Gómez-Olivé FX, et al. Cohort profile: health and ageing in Africa: a longitudinal study of an indepth community in South Africa (HAALSI). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):689–690j.

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs; Population Division. World population ageing 2015. United Nations New York City; 2015. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf. Accessed 16 Nov 2022.

Shlisky J, et al. Nutritional considerations for healthy aging and reduction in age-related chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(1):17.

Batsis JA, et al. Promoting healthy aging during COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):572–80.

Zakirov F, Krasilnikov A. Age-related differences in decision-making process in the context of healthy aging. in BIO web of conferences. EDP Science; 2020.

Öztürk A, et al. The relationship between physical, functional capacity and quality of life (QoL) among elderly people with a chronic disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53(3):278–83.

Hou Y, et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(10):565–81.

Holman D, Salway S, Bell A. Mapping intersectional inequalities in biomarkers of healthy ageing and chronic disease in older English adults. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–12.

Arrospide A, et al. Inequalities in health-related quality of life according to age, gender, educational level, social class, body mass index and chronic diseases using the Spanish value set for Euroquol 5D–5L questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):1–10.

Afshar S, et al. Multimorbidity and the inequalities of global ageing: a cross-sectional study of 28 countries using the World Health Surveys. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–10.

Schumacher B, et al. The central role of DNA damage in the ageing process. Nature. 2021;592(7856):695–703.

Campisi J, et al. From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature. 2019;571(7764):183–92.

Nielsen JL, Bakula D, Scheibye-Knudsen M. Clinical trials targeting aging. Front Aging. 2022;3:820215.

Newman JC, et al. Strategies and challenges in clinical trials targeting human aging. J Gerontol Series A: Biomed Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(11):1424–34.

Harrison DE, et al. Acarbose, 17-α-estradiol, and nordihydroguaiaretic acid extend mouse lifespan preferentially in males. Aging Cell. 2014;13(2):273–82.

Strong R, et al. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid and aspirin increase lifespan of genetically heterogeneous male mice. Aging Cell. 2008;7(5):641–50.

Sun X, et al. How to use a subgroup analysis: users’ guide to the medical literature. JAMA. 2014;311(4):405–11.

Detry MA, Lewis RJ. The intention-to-treat principle: how to assess the true effect of choosing a medical treatment. JAMA. 2014;312(1):85–6.

Little RJ, et al. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1355–60.

Evans WJ. Drug discovery and development for ageing: opportunities and challenges. Phil Trans Royal Soc B: Biol Sci. 2011;366(1561):113–9.

Ridda I, Lindley R, MacIntyre RC. The challenges of clinical trials in the exclusion zone: the case of the frail elderly. Australas J Ageing. 2008;27(2):61–6.

Broekhuizen K, et al. Characteristics of randomized controlled trials designed for elderly: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126709.

Grgic J, et al. Effects of resistance training on muscle size and strength in very elderly adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 2020;50(11):1983–99.

Zheng G, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on inflammatory markers in healthy middle-aged and older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:98.

Williamson PR, et al. The COMET handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18(3):1–50.

UKSPINE annual conference. 2022. Available from: https://www.kespine.org.uk/events/uk-spine-2022-annual-conference. Accessed 13 June 2022.

Maruszczyk K, et al. Implementation of patient-reported outcome measures in real-world evidence studies: analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov records (1999–2021). Contemp Clin Trials. 2022;120:106882.

Holloway I. Qualitative research in health care. UK: McGraw-Hill Education; 2005.

Seale C, et al. Qualitative research practice. Sage; 2004.

Tong A, S.P., Craig J,. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

O’Brien BC, Harris I, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine. 2014;89(9):1245–51.

Justice JN, et al. A framework for selection of blood-based biomarkers for geroscience-guided clinical trials: report from the TAME Biomarkers Workgroup. Gerosci. 2018;40(5):419–36.

Peel N, Bartlett H, McClure R. Healthy ageing: how is it defined and measured? Australas J Ageing. 2004;23(3):115–9.

Crimmins EM. Lifespan and healthspan: past, present, and promise. Gerontol. 2015;55(6):901–11.

Olshansky SJ. From lifespan to healthspan. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1323–4.

Hansen M, Kennedy BK. Does longer lifespan mean longer healthspan? Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(8):565–8.

Muscedere J, et al. Moving towards common data elements and core outcome measures in frailty research. J Frailty Aging. 2020;9(1):14–22.

Tugwell P, et al. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;8(1):1–6.

Buskens E, et al. Healthy ageing: challenges and opportunities of demographic and societal transitions. In: Dijkman B, Mikkonen I, Roodbol P, editors. Older people: improving health and social care. Cham: Springer; 2019.

Jacobzone, S. Ageing and the challenges of new technologies: can OECD social and healthcare systems provide for the future? In: The Geneva papers on risk and insurance - issues and practice, vol. 28, no. 2. Palgrave Macmillan, The Geneva Association; 2003. p. 254–74.

Davis S, Bartlett H. Healthy ageing in rural Australia: issues and challenges. Australas J Ageing. 2008;27(2):56–60.

Peterson JR, Baumgartner DA, Austin SL. Healthy ageing in the far north: perspectives and prescriptions. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2020;79(1):1735036.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants who participated in the workshop conducted at UK SPINE annual conference 27–28 June 2022.

Funding

The study is part of the UK SPINE project and was funded by the respective organisation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MC is Director of the Birmingham Health Partners Centre for Regulatory Science and Innovation, Director of the Centre for the Centre for Patient Reported Outcomes Research and is a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator. MC receives funding from the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, NIHR Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre (SRMRC), NIHR Birmingham-Oxford Blood and Transplant Research Unit (BTRU) in Precision Transplant and Cellular Therapeutics, and NIHR ARC West Midlands at the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Health Data Research UK, Innovate UK (part of UK Research and Innovation), Macmillan Cancer Support, UK SPINE, UKRI, UCB Pharma, GSK and Gilead. MC has received personal fees from Astellas, Aparito Ltd, CIS Oncology, Takeda, Merck, Daiichi Sankyo, Glaukos, GSK and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) outside the submitted work.

OLA receives funding from the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC), West Midlands, NIHR Birmingham-Oxford Blood and Transplant Research Unit (BTRU) in Precision Transplant and Cellular Therapeutics at the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation, Innovate UK (part of UK Research and Innovation), Health Foundation, Gilead Sciences Ltd, Merck, and Sarcoma UK. OLA declares personal fees from Gilead Sciences Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Merck outside the submitted work.

JML is Director of the MRC-Versus Arthritis Centre for Musculoskeletal Ageing Research and receives funding from the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, NIHR SRMRC, Scar Free Foundation, UK SPINE, FOREUM, UKRI and Bayer Healthcare. JML has acted as a consultant to Bayer Healthcare.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The study sponsor and funder had no roles in study design, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Syed, M.A., Aiyegbusi, O.L., Marston, E. et al. Optimising the selection of outcomes for healthy ageing trials: a mixed methods study. GeroScience 44, 2585–2609 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-022-00690-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-022-00690-5