Abstract

The conjunctiva is a highly specialized ocular mucosal surface that, like other mucosa, houses a number of leukocyte populations. These leukocytes have been implicated in age-related inflammatory diseases such as dry-eye, but their phenotypic characteristics remain largely undetermined. Existing literature provides rudimentary data from predominantly immunohistochemical analyses of tissue sections, prohibiting detailed and longitudinal examination of these cells in health and disease. Using recovered cells from ocular surface impression cytology and flow cytometry, we examined the frequency of leukocyte subsets in human conjunctival epithelium and how this alters with age. Of the total CD45+ leukocyte population within the conjunctival epithelium, 87% [32–99] (median) [range] comprised lymphocytes, with 69% [47–90] identified as CD3 + CD56- T cells. In contrast to peripheral blood, the dominant conjunctival epithelial population was TCRαβ + CD8αβ + (80% [37–100]) with only 10% [0-56%] CD4+ cells. Whilst a significant increase in the CD4+ population was seen with age (r = 0.5; p < 0.01) the CD8+ population remained unchanged, resulting in an increase in the CD4:CD8 ratio (r = 0.5;p < 0.01). IFNγ expression was detectable in 18% [14–48] of conjunctival CD4+ T cells and this was significantly higher among older individuals (<35 years, 7[4–39] vs. >65 years, 43[20–145]; p < 0.05). The elevation of CD4+ cells highlights a potentially important age-related alteration in the conjunctival intra-epithelial leukocyte population, which may account for the vulnerability of the aging ocular surface to disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The ocular surface consists of the cornea, corneal–scleral limbus and conjunctiva, closely interrelated with adnexal structures (lacrimal gland, eyelids and lashes) that together are vital for optical clarity, immune and mechanical protection. The conjunctiva is a highly specialized, delicate mucosa comprising of a bi-layered substantia propria underlying a non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium interspersed with goblet cells. It extends from the muco-cutaneous junction of the eyelid margins, lining the posterior surface of the eyelids and reflects forward over the sclera to become continuous with the cornea at the corneal scleral limbus.

The avascular central cornea is largely devoid of immune cells (Knop and Knop 2007), whereas the vascularized conjunctiva contains numerous resident immune cells including intra-epithelial lymphocytes (IELs) (Allansmith et al. 1978; Hayday et al. 2001; Knop and Knop 2005; Knop and Knop 2007). In common with other mucosal sites, the presence of conjunctiva-associated lymphoid tissue provides a local immune microenvironment, which includes the production of immunoglobulins such as IgA that confers immuno-protection to the ocular surface.

Although an abundance of CD3+ cells (including CD8+ cells) has been identified in the human conjunctival mucosa (Hingorani et al. 1997), the subtypes of IELs have not been defined. Non-invasive means of sampling conjunctival leukocytes such as ocular surface impression cytology (OSIC) have been utilized to characterize ocular surface changes in diseases such as dry eye (Baudouin et al. 1997; Brignole et al. 2000; Baudouin et al. 2004), but this methodology has not been extended to afford a comprehensive examination of resident epithelial leukocytes in healthy conjunctiva.

Of interest, is the observation that the severity of ocular surface infections such as microbial or herpetic keratitis is clinically worse in the elderly (van der Meulen et al. 2008) and autoimmune diseases e.g. Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid (Foster 1986; Chan 2001) typically affect people in later life. Dry eye is a ‘multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface’ (2007). It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface (2007). Some studies have demonstrated an increased prevalence of dry eye problems with age (McCarty et al. 1998; Moss et al. 2000; Stern et al. 2010). Despite this, little is known about age-related changes in the leukocyte populations within the ocular surface (Gwynn et al. 1993). The aim of this study was therefore to utilize OSIC in combination with multi-color flow cytometry (Baudouin et al. 1992; Baudouin et al. 1997) to provide a detailed characterization of the frequency of leukocyte subsets in the healthy human conjunctival epithelium and whether these alter with age.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Clinical data collection and patient sampling were undertaken following ethical approval in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Healthy volunteers were defined as individuals with no history or current clinical evidence of ocular, systemic inflammatory or autoimmune disease (including dry eye) (Behrens et al. 2006; 2007), contact lens wear, previous ocular surgery, cataract surgery within 3 months or use of topical ophthalmic medication.

Two separate cohorts were evaluated:

-

Cohort 1

(Figs. 1, 2 and 3): OSIC of right and left eyes of 30 individuals (median age, 61 years [21–83]) together with matched peripheral blood were collected. Twenty out of 30 individuals were White (European) and ten out of 30 were Asian (defined according to the ethnic demographic categories employed in the UK census 2011). Fifteen were male and 15 were female.

Fig. 1 Lymphocytes are the dominant conjunctival epithelial leukocyte population. Conjunctival OSIC of the superior unexposed bulbar conjunctiva is shown in A. Representative plots of a subject demonstrating the gating strategy used to identify conjunctival leukocytes. B, E The forward and side scatter profiles for peripheral blood and OSIC, respectively. Live leukocytes were identified by gating for CD45+ cells that were negative for the dead cell exclusion dye Sytox blue (lower right box in C and F) and back-gated to show the forward and side scatter profiles of the CD45+ live cells (D and G). Percentages are shown for the representative subject (n = 30)

Fig. 2 TCRαβ + CD8αβ + T cells are the dominant population of lymphocytes in the conjunctival epithelium. Representative scatter profile of leukocyte populations derived from matched peripheral blood and conjunctival OSIC from a healthy subject. Data are shown for a representative subject, gated on CD45+ live cells for peripheral blood (a) and conjunctival OSIC (b). CD45RO staining is shown for CD3 + CD56 − TCRγδ − gated CD4 + CD8β − (top panel) and CD8αβ + (bottom panel) cells. Percentages of CD3 + CD56- lymphocytes are shown for the representative subject (n = 30). Statistical comparisons between peripheral blood and conjunctival impression populations of CD8αβ+, CD4+, CD8αα+ and TCRαβ+CD4 − CD8αβ− (double negative; DN) T cells (c–f) were undertaken by the Mann–Whitney U test (NS not significant [P > 0.05], **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Fig. 3 Changes in T cell subsets and memory populations in peripheral blood and conjunctiva with age. Changes in the T cell populations in peripheral blood and conjunctival OSIC for CD3 + CD56− lymphocytes (a), as well as CD8αβ+ and CD4+ subsets (b/c, e/f) with their respective CD45RO frequencies (d, g). Statistical analysis was undertaken by Spearman’s correlation (NS not significant [p > 0.05], *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01) (n = 30)

-

Cohort 2

(Fig. 4): OSIC of right and left eyes were collected and pooled for each of ten healthy individuals (five young; median age, 24 [23–33] and five older; median age, 66 [65–83], p = 0.01) in order to evaluate conjunctival T cell cytokine production. All were White (European) with five males and five females. Samples were pooled in this cohort in order to maximize the yield of cells for cytokine staining.

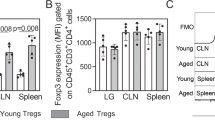

Fig. 4 TCRαβ + CD4+ T cells increase with age but do not alter their cytokine production. Expression of IFNγ, IL-17 and IL-10 in the T cell populations in stimulated peripheral blood (PB) and conjunctival OSIC for CD45 + CD3 + CD56 − CD4+ live lymphocytes (A). Representative figures from a subjects aged <35 and >65 years are shown. The number and percentage of CD4+ T cells are shown for this cohort (B), as well as the number and percentages of cytokine-secreting cells (C). Statistical comparisons were undertaken by the Mann–Whitney U test (NS not significant [p > 0.05], *P < 0.05)

Conjunctival epithelial cell collection and recovery

Collection of conjunctival cells was undertaken with autoclaved synthetic membranes divided in two semi-circles (measuring 13 × 6.5 mm2 each) (Brignole-Baudouin et al. 2004). Supor 200 polyethersulfone filters (0.2 μm membranes) were applied following instillation of 0.4% Oxybuprocaine (as a topical anesthetic). Conjunctival OSIC was performed with four semi-circle membranes per eye (equivalent to two full impressions) from the superior unexposed bulbar conjunctiva for 5–10 s using a sterile technique (Brignole et al. 2000; Brignole-Baudouin et al. 2004) and before the application of topical fluorescein drops for clinical examination (Fig. 1a).

Membranes were removed and placed in 1.5 ml of RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) supplemented with 1% GPS (1.64 mM l-glutamine, 40 U/ml benzylpenicillin, 0.4 mg/ml streptomycin) (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% HEPES buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HIFCS–Biosera Ltd., Ringmer, UK) in a sterile 5-ml universal container and processed within 6 h after OSIC. In order to expedite cellular recovery, the cells were recovered by gentle agitation with a pipette tip for 1 min. Cell suspensions were transferred to a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube and centrifuged (400 × g for 5 min).

The majority of the supernatant was discarded, which was re-suspended in RPMI/10% HIFCS to a total volume of 200 μl (cohort 1) or 100 μl (cohort 2). One hundred microliters of cells were placed into each well of a 96-well plate for flow cytometric analysis.

Preparation of lysed peripheral blood

Peripheral blood was collected in EDTA tubes, centrifuged and re-suspended in 1:10 dilution of filter-sterilized red cell lysis buffer (8.29 g NH4Cl, 1 g KHCO3 and 37.2 mg of EDTA per liter of dH20). After 5 min at room temperature, the suspension was diluted with up to 15 ml of RPMI to block further lysis. Following centrifugation, the pellet was re-suspended in PBS at a concentration of 1 × 107 cells per milliliter and aliquoted at a volume of 100 μl in to individual wells.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was undertaken with a Dako Cyan ADP high performance flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK). Multi-color cytometry compensation was performed using cells or compensation beads individually stained with each fluorochrome conjugated-antibody in order to circumvent spectral overlap by adjusting for false positives from other fluorochromes. An analysis was undertaken with Summit 4.3 for Windows (Dako, CO 2007). Non-parametric comparisons were undertaken with the Mann–Whitney U test, Wilcoxon signed rank test and correlations by Spearman’s correlation using Prism version 5.0 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, CA 2008).

To characterize the cellular profile of the conjunctival ocular surface, nine color flow cytometry panels were developed. Commercially available antibodies to cell surface markers were employed in two panels; panel 1 mouse anti-human CD45RO (FITC), γδTCR (phycoerythrin), CD4 (PerCP Cy5.5), CD45 (allophycocyanin), CD3 (AlexaFluor 780) (Ebioscience, Hatfield, UK); CD8α (Pacific Orange) (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK); CD8β (PE Texas Red) (Beckman Coulter); CD56 (PE Cy7) (Biolegend, Cambridge, UK) and panel 2 mouse anti-human CD16 (FITC), CD45 (Allophycocyanin), CD14 (AlexaFluor 780) (Ebioscience); CD20 (Pacific Orange), CD19 (PE Texas Red) (Invitrogen); CD138 (PerCP Cy5.5) (BD, Oxford, UK) and CD11b (PE Cy7) (Biolegend). These were titrated to determine the optimal concentrations. Each panel was applied to cells recovered from conjunctival OSIC or peripheral blood.

One hundred microliters of cells were placed into 96-well plates (with a cell count per well ranging from 2 × 105–1 × 106 for PBMCs) or 20 μl of positive and negative compensation beads. Cells were centrifuged for 4 min at 1,200 rpm at 4°C, the supernatant removed and the 96-well plate gently vortexed. Cells were stained with surface marker antibodies (made up in 50 μl at appropriate dilutions) and incubated on ice in the dark for 20 min. One hundred microliters of PBS/0.5% BSA was added to each well prior to further centrifugation and removal of supernatant. Cells were re-suspended in 295 μl of FACS and 5 μl counting beads (1,002 beads per microliter) buffer prior to analysis. For dead cell exclusion, 30 μl Sytox blue (Invitrogen) was added at a concentration of 1/800 to the FACS tubes and incubated for 5 min prior to running on the flow cytometer.

Intracellular cytokine staining

For cytokine assays, conjunctival and lysed peripheral blood cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-mysristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich) and ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, cells were incubated in 200 μl containing PMA (250 ng/ml), ionomycin (250 ng/ml) and Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) 2 ug/ml for 3 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

A Live/Dead fixable yellow dye (Invitrogen) was used to discriminate dead cells. Cells were suspended in 100 μl of 1:1,000 Dye/DMSO for 30 min on ice in the dark.

An additional panel was utilized to determine cytokine expression by T cell subsets: mouse anti-human IFNγ (eFluor 450) (Ebioscience), IL-17 (FITC) (Ebioscience), CD4 (PerCP Cy5.5), CD45 (Allophycocyanin), CD3 (AlexaFluor 780) (Ebioscience), CD8β (PE Texas Red) (Beckman Coulter), CD56 (PE Cy7) (Biolegend) and rat anti-human IL-10 (Phycoerythrin) (Biolegend). For cytokine assays, surface marker antibodies in this panel were suspended in Fixation Medium A (Fix & Perm, Invitrogen) under the same conditions as described for “Flow cytometry.” Intracellular antibodies were suspended in Permeabilization Medium B (Fix & Perm, Invitrogen) on ice in the dark for 20 min before centrifugation and re-suspension as described.

Results

Defining resident conjunctival leukocyte populations

Conjunctival OSIC (Fig. 1a) and matched peripheral blood samples were taken from healthy subjects and recovered cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Whilst the light scatter profile for peripheral blood clearly delineated each leukocyte population (Fig. 1b), it was not possible to make this discrimination from OSIC (Fig. 1e). This was overcome by gating on CD45+ live cells, which permitted demonstration of lymphocytes as the dominant leukocyte population in the conjunctival epithelium (Fig. 1f, g). This approach also clarified the identity of the leukocyte populations found in peripheral blood (Fig. 1c, d).

There were no differences in the number of leukocytes between the right and left eyes (p = 0.23; Wilcoxon signed rank test) and right and left eye leukocyte numbers highly correlated (r = 0.72; p < 0.0001). Therefore, the mean of the right and left eyes for each subject was calculated (i.e. the right and left eyes per individual subject were considered to be experimental duplicates). CD45+ live leukocytes accounted for a median 834 [range, 6017,635] of total events. Of the cohort of 30 subjects (median age, 61 years [21–83 years]), the dominant conjunctival leukocyte population was lymphocytes (median, 89% [32–99%]) as defined by their forward and side scatter profiles; 9% [0–34] were monocytes and 1% [0–66] were neutrophils. This compared to 52% [18–75], 5% [3–28] and 42% [19–76], respectively in matched peripheral blood.

T and NK cell subsets were defined by the expression of CD3 and CD56 (Fig. 2). T cells (CD3 + CD56−) dominated in both conjunctival OSIC (69% [47–90]) and in matched peripheral blood (74% [57–84]), and these were >98% TCRγδ-(TCRαβ+) in both (Fig. 2a, b). T cells were further characterized by the expression of the CD4, CD8α and CD8β cell surface co-receptors (Fig. 2a, b). Unlike in the peripheral blood where the dominant T cell population was CD4+ (Fig. 2d; 69% [45–91]), the dominant population from the conjunctival impression was CD8αβ+ (Fig. 2c, 80% [37–100]). The majority of CD4+ and CD8αβ+ T cells were CD45RO+ in the conjunctival epithelium (100% [0–100] and 94% [55–100], respectively), higher than the proportion of antigen experienced populations in blood (61% [0–90] and 56% [20–86], respectively). CD4−CD8αβ− (DN) T cells accounted for only 7.3% [0.7–22] and 3.5% [0.4–26] of conjunctival and peripheral blood T cells, respectively (Fig. 2e). Whilst CD8αα+ cells formed the minority of T cells, these were significantly higher in the conjunctiva than in peripheral blood (Fig. 2f; 2.6% [0–12.5] versus 1.4% [0.1–4.4] (p < 0.001)).

NK cells represented 7% [0–20] of conjunctival epithelial lymphocytes compared with 9% [0–22] in the peripheral blood. There was also a greater proportion of NKT (CD3 + CD56+) cells (conjunctiva 6% [0–17] versus peripheral blood 2% [0–6] (p > 0.05)) but fewer CD19 + CD20+ B cells (3% [1–45] versus 9% [3–23], respectively, (p < 0.0001)).

Age-related changes in leukocyte populations in the healthy human conjunctival epithelium

Changes in leukocyte populations with age were determined in this cohort (Table 1). Analysis of peripheral blood monocyte, neutrophil and lymphocyte frequencies showed that the only change was a decrease with age in lymphocytes calculated as a percentage of total leukocytes (Table 1). This was not observed in cells recovered from the conjunctival epithelium. By contrast, conjunctival cells showed an increase in the absolute numbers of lymphocytes and monocytes (but not neutrophils), resulting in a significant increase in the total number of leukocytes (Table 1).

Within the conjunctival epithelial lymphocyte population there was an age-related decrease in the proportion of T cells (Fig. 3a; Table 2), compensated for by an increase in the percentage of NK cells (Table 2). The dominant CD8αβ + cell population remained unchanged in the conjunctival epithelium with age but decreased in peripheral blood (Fig. 3b; Table 2). Conversely, the absolute number of CD4+ cells significantly increased in the conjunctiva but remained unchanged in peripheral blood (Fig. 3e; Table 2). This resulted in proportional changes in CD8αβ + and CD4+ lymphocytes (Fig. 3c and f; Table 2) with a consequent increase in the CD4/CD8 ratio with age (Table 2). In addition, the CD45RO + memory population increased in the peripheral blood with age, a change that was not seen in conjunctival OSIC (Fig. 3d and g; Table 2), reflecting the high proportion of antigen experienced CD8+ (93%) and CD4+ cells (100%) present in the conjunctival epithelium from a young age.

The conjunctival CD4+ T cell populations of the cohort of five additional healthy younger (<35 years) and five older subjects (>65 years) were characterized for the expression of IFNγ, IL-17 and IL-10 following stimulation with PMA/ionomycin (Fig. 4a). The CD4+ population was significantly elevated in the older age group (19% [11–52) vs. those <35 years] (4% [2–13]; p = 0.02) (Fig. 4b).

Eighteen percent [14–48] of conjunctival CD4+ T cells were capable of expressing IFNγ, 3.5% [0–22] IL-17 and 0% [0–4] IL-10. The absolute number of CD4+ T cells able to secrete IFNγ was significantly elevated with age (<35 years, 7[4–39] vs. >65 years, 43 [20–145]; p = 0.03) while the percentage of IFNγ + CD4+ remained unchanged (17% [14–35] vs. 18% [16–48], p = NS, respectively) (Fig. 4c). Changes in IL-17 and IL-10 producing CD4+ T cells were not observed with age (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

OSIC offers a non-invasive sampling technique which when combined with multicolor flow cytometric analysis of the recovered cells enables a comprehensive characterization of the conjunctival epithelial leukocytes superficial to the basement membrane zone. In this study, we have utilized this methodology to describe a detailed phenotyping of conjunctival leukocytes in a cohort of healthy individuals and how these change with age. We have identified that the dominant conjunctival epithelial leukocyte population is CD3+CD56 − TCRαβ+CD8αβ+ lymphocytes. Interestingly, although this population remained unchanged with age, there was an increase in the conjunctival epithelial CD4+ population resulting in an alteration in the CD4/CD8 ratio. We have demonstrated that 14–48% of conjunctival epithelial CD4+ cells were capable of producing IFNγ and 0–22% were capable of producing IL-17. This was maintained in older subjects and given the increase in absolute numbers of CD4+ cells with age, this resulted in a substantial increase in the number of pro-inflammatory conjunctival CD4+ T cells.

The role of conjunctival IELs is unresolved. In other mucosal tissues, two subtypes of IEL have been defined: type a (TCRαβ+CD8αβ+) ‘conventional’ and type b (TCRαβ+ CD8αα+, TCRγδ+ CD8αα+ and TCRγδ+ double negative (DN)) IELs, with differing roles in effector function and regulation (Hayday et al. 2001). Type b IELs are thought to represent an interface between the innate and adaptive immune response and are also implicated in the repair of damaged mucosa. Function is dependent on additional activation, and in their resting state a number of anti-proliferative genes are expressed e.g. Btg1 and 2. This has given rise to the concept of being ‘activated but resting’ (Hayday et al. 2001). Our study suggests that the dominant IEL population in the human conjunctiva is ‘conventional’ (type a) TCRαβ+CD8αβ+ with less than 1% TCRγδ+. Whether TCRγδ+ cells have a relatively minor role to play in conjunctival epithelial biology, or are confined to below the basement membrane zone within the substantia propria (which we were unable to sample using OSIC) remains unknown.

Tissue-based immunohistochemical analyses identified CD45RO + cells (75–100%) in the bulbar conjunctiva (Hingorani et al. 1997), but those studies were limited as precise T cell subsets were not quantified. Our data showed that antigen experience (defined by the expression of CD45RO) was evident in all CD4+ and almost al (median 94%) of CD8αβ+ conjunctival epithelial T cells, whereas a significant increase in the CD8αβ+ and CD4+ CD45RO + T cell population was observed in peripheral blood, in keeping with the findings of others (Saule et al. 2006; Utsuyama et al. 2009). The predominance of CD45RO + lymphocytes in the conjunctival epithelium is expected and consistent with the preferential recruitment of memory cells into mucosal tissues.

The major alteration in IELs was an increase in the number and percentage of CD4+ cells with age. This resulted in a reduction in the percentage of the dominant conjunctival CD8αβ+ population and an increase in the CD4/CD8 ratio. By contrast, there was a decrease in the number of CD8αβ + T cells in blood, although this too resulted in an increase in the CD4/CD8 ratio, as previously reported by Utsuyama et al (Utsuyama et al. 2009).

As the proportion of T cells decreased in the conjunctival epithelium with increasing age, both the proportion and number of NK cells, increased. Although this observation has been previously described in peripheral blood (Borrego et al. 1999) (and there was an observed trend in our cohort) this is the first time those changes have been defined in the conjunctiva. Whether this represents an accumulation of NK cells in the ocular surface reflecting immune senescence, or a direct response to a specific change in ocular surface antigen exposure, remains unknown.

It is clear that the changes in IEL populations seen in our cohort, in particular the increased TCRαβ+ CD4+ T cell population, have implications for age matching when undertaking comparisons with disease populations, specifically in relation to infective or immune-mediated processes affecting the ocular surface. Dry-eye problems increase with age (Draper et al. 1999) including dry eye disease (McCarty et al. 1998; Moss et al. 2000). Although changes to the lacrimal acinar gland have been attributed to age-related ocular surface dryness (Draper et al. 1999), dry eye syndromes (including Sjögren’s syndrome and non-Sjögren’s syndrome-related dry eye) are thought to have an underlying inflammatory and autoimmune component.

Intriguingly, elevations of CD4+ T cells in both humans and in animal models of dry eye have been identified (De Paiva et al. 2010; Stern et al. 2010), but the contribution of elevated conjunctival intraepithelial CD4+ cells to a pro-inflammatory state is not known and may offer clues to dry eye vulnerability amongst older subjects. The absolute number of CD4+ T cells able to secrete interferon-γ was significantly elevated with age and IL-17 producers were maintained with age in this study. An elevation of IFNγ and IL-17 producing cells has been identified in the conjunctiva in murine models of dry eye (De Paiva et al. 2009). Furthermore, an increase in these cytokines is seen in tears of human subjects with dry eye disease (De Paiva et al. 2009). Whether age-associated accumulation of CD4+ cells predisposes to dry eye problems by an increased number of IFNγ and IL-17 secreting cells or whether an alteration in function occurs under dry eye conditions in humans, remains to be defined.

In murine models, there appears to be a defective suppressor function by T regulatory cells on Th17 cells (Chauhan et al. 2009). Few conjunctival CD4+ T cells were capable of producing IL-10 in this study, and no changes were observed with age. The expression of the transcription factor FoxP3 was seen in approximately 2% of CD3+ conjunctival T cells (data not shown). This suggests that in the healthy conjunctival epithelium, there is not a significant population of CD4+ T cells with an IL-10+ or FoxP3+ regulatory phenotype. An increase in the stromal CD4+ population has also been identified from histological conjunctival sections (Bernauer et al. 1993) taken from patients with Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid, a disease characterized histologically by antibody deposition in the basement membrane zone with subsequent conjunctival inflammation, scarring, corneal limbal epithelial stem cell failure and ocular surface keratinization (Foster 1986; Chan et al. 2002; Liesegang 2008), that typically affects older patient populations (although disease activity and progression is worse in younger patients) (Rauz et al. 2005).

The possibility of utilizing a non-invasive sampling technique such as OSIC to characterize changes in supra-basement membrane structures of the ocular mucosa in the context of infectious and non-infectious disease affords an attractive method for both cross-sectional and longitudinal research into human ocular surface inflammatory disease. The importance of aging on conjunctival leukocyte profiles in disease states is yet to be elucidated, but has implications in forming comparative healthy control cohorts, indicating that age-matching is essential.

References

The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007;5:75–92

Allansmith MR, Greiner JV, Baird RS (1978) Number of inflammatory cells in the normal conjunctiva. Am J Ophthalmol 86:250–259

Baudouin C, Brignole F, Becquet F, Pisella PJ, Goguel A (1997) Flow cytometry in impression cytology specimens. A new method for evaluation of conjunctival inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38:1458–1464

Baudouin C, Hamard P, Liang H, Creuzot-Garcher C, Bensoussan L, Brignole F (2004) Conjunctival epithelial cell expression of interleukins and inflammatory markers in glaucoma patients treated over the long term. Ophthalmology 111:2186–2192

Baudouin C, Haouat N, Brignole F, Bayle J, Gastaud P (1992) Immunopathological findings in conjunctival cells using immunofluorescence staining of impression cytology specimens. Br J Ophthalmol 76:545–549

Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L, Chuck RS, McDonnell PJ, Azar DT, Dua HS, Hom M, Karpecki PM, Laibson PR, Lemp MA, Meisler DM, Del Castillo JM, O'Brien TP, Pflugfelder SC, Rolando M, Schein OD, Seitz B, Tseng SC, van Setten G, Wilson SE, Yiu SC (2006) Dysfunctional tear syndrome: a Delphi approach to treatment recommendations. Cornea 25:900–907

Bernauer W, Wright P, Dart JK, Leonard JN, Lightman S (1993) The conjunctiva in acute and chronic mucous membrane pemphigoid. An immunohistochemical analysis. Ophthalmology 100:339–346

Borrego F, Alonso MC, Galiani MD, Carracedo J, Ramirez R, Ostos B, Peña J, Solana R (1999) NK phenotypic markers and IL2 response in NK cells from elderly people. Exp Gerontol 34:253–265

Brignole-Baudouin F, Ott AC, Warnet JM, Baudouin C (2004) Flow cytometry in conjunctival impression cytology: a new tool for exploring ocular surface pathologies. Exp Eye Res 78:473–481

Brignole F, Pisella PJ, Goldschild M, De Saint JM, Goguel A, Baudouin C (2000) Flow cytometric analysis of inflammatory markers in conjunctival epithelial cells of patients with dry eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41:1356–1363

Chan LS (2001) Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Clin Dermatol 19:703–711

Chan LS, Ahmed AR, Anhalt GJ, Bernauer W, Cooper KD, Elder MJ, Fine JD, Foster CS, Ghohestani R, Hashimoto T, Hoang-Xuan T, Kirtschig G, Korman NJ, Lightman S, Lozada-Nur F, Marinkovich MP, Mondino BJ, Prost-Squarcioni C, Rogers RS 3rd, Setterfield JF, West DP, Wojnarowska F, Woodley DT, Yancey KB, Zillikens D, Zone JJ (2002) The first international consensus on mucous membrane pemphigoid: definition, diagnostic criteria, pathogenic factors, medical treatment, and prognostic indicators. Arch Dermatol 138:370–379

Chauhan SK, El Annan J, Ecoiffier T, Goyal S, Zhang Q, Saban DR, Dana R (2009) Autoimmunity in dry eye is due to resistance of Th17 to Treg suppression. J Immunol 182:1247–1252

De Paiva CS, Chotikavanich S, Pangelinan SB, Pitcher JD 3rd, Fang B, Zheng X, Ma P, Farley WJ, Siemasko KF, Niederkorn JY, Stern ME, Li DQ, Pflugfelder SC (2009) IL-17 disrupts corneal barrier following desiccating stress. Mucosal Immunol 2:243–253

De Paiva CS, Hwang CS, Pitcher JD 3rd, Pangelinan SB, Rahimy E, Chen W, Yoon KC, Farley WJ, Niederkorn JY, Stern ME, Li DQ, Pflugfelder SC (2010) Age-related T-cell cytokine profile parallels corneal disease severity in Sjogren's syndrome-like keratoconjunctivitis sicca in CD25KO mice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49:246–258

Draper CE, Adeghate EA, Singh J, Pallot DJ (1999) Evidence to suggest morphological and physiological alterations of lacrimal gland acini with ageing. Exp Eye Res 68:265–276

Foster CS (1986) Cicatricial pemphigoid. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 84:527–663

Gwynn DR, Stewart WC, Hennis HL, McMillan TA, Pitts RA (1993) The influence of age upon inflammatory cell counts and structure of conjunctiva in chronic open-angle glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 71:691–695

Hayday A, Theodoridis E, Ramsburg E, Shires J (2001) Intraepithelial lymphocytes: exploring the Third Way in immunology. Nat Immunol 2:997–1003

Hingorani M, Metz D, Lightman SL (1997) Characterisation of the normal conjunctival leukocyte population. Exp Eye Res 64:905–912

Knop E, Knop N (2005) The role of eye-associated lymphoid tissue in corneal immune protection. J Anat 206:271–285

Knop E, Knop N (2007) Anatomy and immunology of the ocular surface. Chem Immunol Allergy 92:36–49

Liesegang TJ (2008) Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology 115:S3–S12

McCarty CA, Bansal AK, Livingston PM, Stanislavsky YL, Taylor HR (1998) The epidemiology of dry eye in Melbourne, Australia. Ophthalmology 105:1114–1119

Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE (2000) Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 118:1264–1268

Rauz S, Maddison PG, Dart JKG (2005) Evaluation of mucous membrane pemphigoid with ocular involvement in young patients. Ophthalmology 112:1268–1274

Saule P, Trauet J, Dutriez V, Lekeux V, Dessaint J-P, Labalette M (2006) Accumulation of memory T cells from childhood to old age: central and effector memory cells in CD4(+) versus effector memory and terminally differentiated memory cells in CD8(+) compartment. Mech Ageing Dev 127:274–281

Stern ME, Schaumburg CS, Dana R, Calonge M, Niederkorn JY, Pflugfelder SC (2010) Autoimmunity at the ocular surface: pathogenesis and regulation. Mucosal Immunol 3:425–442

Utsuyama MKY, Kitagawa M et al (2009) Handbook on immunosenescence: basic understanding and clinical applications. Springer, Dordrecht

van der Meulen IJ, van Rooij J, Nieuwendaal CP, Van Cleijnenbreugel H, Geerards AJ, Remeijer L (2008) Age-related risk factors, culture outcomes, and prognosis in patients admitted with infectious keratitis to two Dutch tertiary referral centers. Cornea 27:539–544

Acknowledgments

The Academic Unit of Ophthalmology is supported by the Birmingham Eye Foundation (UK Registered Charity 257549). Geraint P. Williams if funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, G.P., Denniston, A.K.O., Oswal, K.S. et al. The dominant human conjunctival epithelial CD8αβ+ T cell population is maintained with age but the number of CD4+ T cells increases. AGE 34, 1517–1528 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-011-9316-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-011-9316-3