Abstract

The study aims to assess and analyze the social outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study uses the discourse of comprehensive literature review to identify the outcomes, Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) for developing a structural model and Matrices’ Impacts Cruise’s Multiplication Appliquée a UN Classement (MICMAC) for analysis, classification of societal outcomes, and corroboration of results of ISM. Data from fifteen experts was collected through a survey questionnaire. As a result of the literature review, a list of sixteen outcomes was generated and verified by a panel of experts. Results of ISM revealed that the outcomes, namely, “emotional instability,” “mental health self-harm,” loneliness reduced recreational activities, obesity, and “increased screen time” come at the top of the model; therefore, they are less vital outcomes, whereas the most significant outcome which is at the bottom of the model is “employment instability”; hence it has a major impact on the society. The remaining outcomes fall in the middle of the model, so they have a moderate-severe impact. Results of MICMAC validate the findings of ISM. Overall findings of the study reveal that “employment instability” is the crucial social outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is an original attempt based on real-time data, which is helpful for society at large, researchers, the international community, and policymakers because this study provides a lot of new information about the phenomenon. The study includes understanding society at large, policymakers, and researchers by illustrating the complex relations and simplifying the connections among a wide range of social outcomes of COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

World Health Organization declared coronavirus as a global pandemic initially identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Later it spread to European countries, the USA, and worldwide. This pandemic has taken millions of lives to date. Healthcare departments, technological people, and people in different fields all around the globe were unprepared for what they were about to face. Such challenging and changing situations and qualms, where the death toll and mortality rates are high (Atif & Malik 2020; Yang and Usman 2021; Dietz & Santos-Burgoa 2020), have forced people to live in a quarantine lockdown situation. People are obligated to work from home and are in a state of panic about how they will survive through these circumstances (Wilson et al. 2020). There is plenty of literature that tells that the pandemic has brought a fair share of advantages like families are coming closer and spending more time with each other, playing indoor games, and doing chores. Some of them (upper-class families in particular) are happy and comfortable being quarantined, but in some cases (e.g., middle class, educated, and jobholders), it is the other way round. Middle-class, educated, and job holders are worried about meeting the necessities of life (Usman and Balsalobre-Lorente 2022; Wilson et al. 2020). This worry creates the tension of risk decline/discontinuity of livelihood that can ultimately lead them to fear, anxiety, frustration, boredom, emotional instability, etc. (Banerjee & Rai 2020; Peters & Bennett 2020; Szabo et al. 2020; Waris et al. 2020; Abbass et al. 2021a; Williams et al. 2020). The impact of this pandemic is just beyond the mortality and deaths alone. As families and individuals have to stay in isolation, lockdown situation has been prolonged, no recreational activities for kids and elders; with these circumstances, people are facing a multitude of problems like stress, fear, frustration, boredom, emotional instability, depression, and, the most critical factor, the risk of making ends meet. With the outbreak of pandemic and influx of research, literature (published/unpublished) also erupted into the panorama, e.g., Waris et al. (2020) asserted that treatments for people who were fighting with the disease, other people who were homebound, and daily routine activities were stopped. Many people lost their jobs and were facing anxiety, stress, and mental health issues (Holmes et al. 2020; Kesar et al. 2021); Huang et al. (2022); Mamun and Ullah (2020) stated that there are many risk factors of COVID-19 ordinary in many countries, such as social isolation and social distancing, economic recession, exacerbated poverty, and mental health problems, including unavailable or poorly managed healthcare facilities. Rana et al. (2020) found that healthcare workers face extreme anxiety and stress because they work in high-stressed physical environments. Atif and Malik (2020) bolstered that Pakistan is relatively more vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic because of limited resources allocated to healthcare systems. Khan et al. (2020) concluded that people responsible for running the health systems in countries worldwide were not mentally or physically prepared for this looming and threatening disease. Saqlain et al. (2020) affirmed that dealing with COVID-19 is likely to engage everyone right from the head of state to the ordinary person and demands to work together in the country’s best interest.

Despite media claims that the COVID-19 pandemic is bringing societies closer in this challenging time, reality seems the other way round because there are a lot of instances of being all alone in this trouble. People face the fear of getting infected, how to earn, and how to work from home while just sitting at home idle and just eating. They are also scared about not getting proper medical treatments on time, especially with poor financial conditions. Due to fear of not getting timely medical help to save lives, people are under stress and depression, and in this way, they ultimately land into the thoughts of harming themselves. It has become imperative to study this type of outcome of COVID-19 seriously, rigorously, and compressively. The significance of this study is that it will help by providing a lot of new information to all stakeholders. It will create awareness about mental health situations that contemporary studies usually ignore (Usman et al. 2021). To be more exact, there are many counter effects of the COVID-19 pandemic to which society at large, policymakers, and other stakeholders cannot understand appropriately. The gravity of not understanding the counter effects of this pandemic can create havoc as aftermath. Therefore, this study is aimed to (i) identify social outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic, (ii) analyze and develop a structural model of the outcomes, (iii) substantiate results of the structural model, and discuss the results of the study in contrast to realities. To achieve the objectives of this research study, ISM and MICMAC methodologies are selected because it has some benefits over rival methods (Abbass et al. 2021b; Abbass et al. 2022; Usman et al. 2022; Shaukat et al. 2021). The study is divided into different parts: literature review, methodology/data collection, modeling/analysis/results and discussion, and conclusion.

Literature review

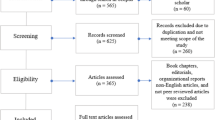

Keeping in view the utmost importance of reviewing contemporary literature necessary for setting the study’s outset, a detailed literature review is done. The authors explored all renowned databases containing scientific literature, e.g. JStor, Emerald, Elsevier (Science Direct), Willey Blackwell, Sage, Hindawi, Karger, etc. Keywords used to search literature included COVID-19 pandemic, coronavirus, social outcomes of COVID-19, the socio-economic impact of coronavirus, societal outcomes of COVID-19 pandemic, effects of COVID-19 on society, etc. We come across many research studies from different perspectives, including published, accepted for publications, and unpublished. The literature is screened based on the degree of relevance. It is pertinent to document some of the relevant research studies across the globe before embarking on the topic to set the outset of the survey, viz., a study of investigation on human stress during COVID-19 pandemic and its relation with other relevant factors in Bangladesh (Amit et al. 2021); a study on distress, anxiety, and depression that collected data from 15,704 German residents to analyze the mental health of German general public during COVID-19 (Bäuerle et al., 2020); a study on socio-economic crises in Italy (Cerami et al., 2020); research study on self-harm, suicidal ideation, and harm in the UK during COVID-19 (Iob et al., 2020), an articles on effects of COVID-19 pandemic in India: a threat of life and livelihood (Krishnakumar & Rana, 2020); a research study on development of mental health service during COVID-19 pandemic in China (Li et al. 2020); a research study on COVID-19 outbreak and its impact on social and mental health of children and youngsters that examines the sample data before and during COVID-19 period in Netherland; a research article analyzing the mental and physical health of 13,002 athletes in USA (McGuine et al., 2021); a study examining the relationship of sociodemographic factors with emotional wellbeing of youngsters in Brazil during COVID-19 (Szwarcwald et al., 2021); and a study of recreational opportunities during COVID-19 pandemic in Oslo, Norway (Venter et al. 2020), etc. In this way, a wide variety of research literature is found in the research mentioned above databases.

Further, Banerjee and Rai (2020) and Williams et al. (2020) asserted that social distancing and isolation effectively mitigate the transmission of a novel coronavirus. Still, it induces boredom and loneliness, causing damage to psychological and physical health. Dietz and Santos-Burgoa (2020) and Onder et al. (2020) that the increased prevalence of obesity in the COVID-19 outbreak is associated with high mortality. Islam et al. (2020) affirmed that COVID-19 had created fear and stress, resulting in chaos in the family life cycle, short temper, fetter sound sleeps, and even suicidal ideation. Kesar et al. (2021) collected data from five thousand respondents across twelve states of India and argued that the COVID-19 pandemic is causing food insecurity, greater unemployment, and livelihood. Killgore et al. (2020) argued that loneliness had become a critical public health concern in the COVID-19 pandemic that is significantly associated with suicidal ideation and depression. Szabo et al. (2020) buttressed that the COVID-19 pandemic urged behaviorists to develop new skills/activities for parents to manage a home environment that promotes the emotional wellbeing and health of the children/family. Wang et al. (2021) gathered data from 4479 Asians of seven middle-income countries of Asia (Iran, China, Malaysia, Philippines, Pakistan, Vietnam, and Thailand) to examine the COVID-19 pandemic impacts on social, economic, and mental health and revealed that it has a severe impact on social, economic, physical, psychological,and livelihood of people worldwide. Literature shows that mental illness is widely prevalent, totally dependent on people’s circumstances and conditions. People are facing depressive disorders to that they are unaware. The irony is that mental healthcare access is minimal, specifically in underdeveloped and developing countries, worsening the situation. In a pandemic, this problem is exacerbated because mental health needs are going unnoticed due to limited resources. COVID-19 era has changed the overall living lifestyle of the communities (Egede et al., 2020). This abridged literature representation helped us prepare a list of outcomes (Table 1).

Initially, the literature review prepared a list of social outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic and presented the same to a panel of experts to solicit opinions about the social consequences qua reality. The experts were asked to assess relevance, appropriateness, and sufficiency; they were given the option to add, merge and/or delete the outcome from/within the list. As a result of this process, we generated a list of sixteen outcomes subject to study.

Methodology/data collection

With interpretivism as an epistemological orientation, the study follows an inductive, exploratory approach. The survey design includes a detailed literature review: data collection through field survey, analysis, and structural modeling. The study uses the discourse of comprehensive literature review for identification of the outcomes, Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) for developing a structural model, and Matrices’ Impacts Cruise’s Multiplication Appliquée a UN Classement (MICMAC) for analysis, classification of societal outcomes, and corroboration of results of ISM. Data from fifteen experts collected through a survey questionnaire were explained in a one-on-one survey face-to-face. The population under study is the individuals from the middle-income class of the society because they are sensitive to periodical income and survival shocks. The sampling strategy is purposive sampling, and respondents are chosen on pre-determined criteria based on the study’s objectives. Using this sampling technique makes it possible to reach the targeted sample objectively in the given time. Initially, twenty respondents (experts) were invited to participate in the study, and ultimately only eighteen completed and participated in the research but found some of the surveys stereotype/invalids. There are different techniques for finalizing the variables for study, and there is a wide variety of eliciting the data from respondents (Shaukat et al., 2021). According to ISM norms, primary data is collected from a pre-constituted panel of experts (Niazi et al., 2019a, b). As the data related to this study did not exist, forming the panel of experts is appropriate for keeping the concept of model exchange isomorphism. Fifteen valid responses are used in analysis, modeling, and classification. The data is collected through a field survey using a matrix type VAXO-based questionnaire. Respondents were explained and guided one-on-one face-to-face to establish the ‘leads to’ relationship among the factors with the instructions: (i) fill the white cells only, (ii) not to fill the black and grey cells, (iii) enter V when the row is leading to the column, (iv) enter A when the column is leading to the row, (v) enter O when there is no relation between row and column and enter X when row, and (vi) column is leading to each other. The step-wise classical procedure of ISM is adopted from Abbass et al. (2021b) .

Panel of experts

A panel of experts is constituted according to the rules and norms of ISM for generating the primary data. The panel of experts is usually selected and created when the data does not exist/is unreliable, the data is limited, or the data collection process is expensive. The data does not exist in this scenario, and collecting data from the general public and/or statistical sample is neither possible nor feasible/practicable/meaningful. Therefore, it is appropriate to go for non-probability sampling (particularly purposive sampling). There are two types of purposive samples, i.e., homogenous and heterogeneous. It depends upon the context of the study to opt from within heterogeneous or homogenous. Usually, 8–12 experts are sufficient on the heterogeneous panel and 12–20 experts on the homogeneous panel. Since this study uses a homogeneous panel, a set of data taken from fifteen experts (valid responses for this study) suffice to support the study (Jena et al. 2017). To recruit the experts on the panel, the usual criteria are theoretical knowledge related to the topic, practical experience, and the capability of understanding the phenomenon. For the study, the experts recruited on the panel from middle-income class families with additional qualifying criteria being: (i) university graduate in social sciences so that they should be able to understand the questionnaire and context, (ii) job holders in middle-level management in some national or multi-national companies, (iii) coming from the area that was predominantly affected by COVID-19 pandemic and resultant lockdowns, (iv) experienced corona infection himself or at least one of the family members, (v) aware of the implications of COVID-19 pandemic in general, and (vi) willing to participate in this study. Initially, 25 experts were identified, briefed, and invited to participate in the study, out of which only 20 were agreeable, and 18 practically participated in this study. A perusal of the collected data revealed that only 15 responses are correct, appropriate, and useable for the study. Therefore, for all practical purposes, the panel of respondents consists of 15 respondents. It took us more than 2 months to complete the process of data collection. Visits were being done after taking an appointment on calls to the experts. There are different methods of practically eliciting the data from people’s minds (Niazi et al. 2019a, b; Qazi et al. 2020). We stimulated the data on VAXO-based matrix using face-to-face, one-on-one method. There were two stages to involve the panel; the first stage was variable verification/data collection; and the other stage was model verification. After this, the model was being developed and requested a panel of experts again to check and review it conceptually and theoretically, after the thorough explanation of the model to them.

Modeling/analysis/results and discussion

Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM)

The data were put in an MS Excel sheet and is aggregated: (i) by applying the “count if” function for counting responses on paired alternatives and (ii) by applying “majority rule” to opt for an alternative for each paired relation. Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM) is developed from the aggregated data (Table 2).

The initial reachability matrix (Table 3) was developed by applying classical rules of converting SSIM into binary codes (Warfield 1973).

Given the presence of transitivity, all the 0 s in the initial reachability matrix (Table 3) are evaluated, and some of the 0 s are changed with 1* (indicating the existence of transitive relations). The transitive relations are scientifically detected using appropriate functions of MS Excel. A fully transitive matrix (Table 4) is extracted due to seeing transitivity.

The iteration method (Warfield 1973, 1974) is used to partition the fully transitive matrix (Table 4) that resulted into four iterations (Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Conical matrix is prepared through permuting from the level partitioning aforementioned. It is not out of context to present the abridged form of ISM analysis (Table 9). It is nothing more than offering the ISM process in condensed form.

The grey cells indicate the extraction of the ISM model on diagonals which is transformed into a graphical representation as ISM model (Fig. 1).

The ISM model reveals that the outcomes coded as 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, and 12 fall on Level I. The outcomes coded as 3, 6, 9, 10, 13, 14, and 15 fall at Level II. The outcome coded as 16 falls at Level III, and the outcome coded as one falls at Level IV. All the outcomes have two-way relations at levels.

MICMAC analysis

MICMAC analysis is performed in Fig. 2 to support the findings of the ISM method. That follows scale centric approach; we divided the Cartesian plane into four quadrants, i.e., independent, autonomous, and dependent and linkage.

Suppose we observe the driving-dependence diagram, the outcome coded as 1 is categorized in the independent quadrant. Outcomes coded as 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16 are categorized in linkage quadrant, whereas no outcome falls under autonomous and dependent quadrant; however, outcome coded as 5 is a marginal case having the potential of becoming dependent.

Results

The study aims to assess and analyze the social outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Outcomes are identified from the literature, data concerning the paired relationships among outcomes are collected from experts, and the ISM method is used for modeling and the MICMAC method for analysis. Sixteen primary outcomes surfaced as a review of literature that is the subject matter of the research study (Table 1). Results of the ISM model show that the outcomes emotional instability (2), mental health (4), suicide/self-harm (5), loneliness (7), reduced recreational activities (8), obesity (11), and increased screen time (12) fall on Level I. The outcomes distress (3), change in interaction with family (6), boredom (9), increased leisure time (10), less productivity (13), fear of getting infected (14), and low self-esteem (15) fall at Level II. The outcome risk of livelihood (16) falls at Level III, and the outcome employment instability (1) falls at Level IV. The factors (outcomes in this case) that occupy the model’s top are less critical to the system. Factors that occupy the middle of the model have moderate acute effects, and the factors at the bottom of the model are the most vital to the system. Accordingly, the outcome “employment instability” (1) is the most critical one in this case. Results of MICMAC show that employment instability outcome (1) is independent, whereas emotional instability (2), distress (3), mental health (4), suicide/self-harm (5), change in interaction with family (6), loneliness (7), reduced recreational activities (8), boredom (9), increased leisure time (10), obesity (11), increased screen time (12), less productivity (13), fear of getting infected (14), self-esteem (15), and risk of livelihood (16) are linking, whereas, no outcome is autonomous and dependent. Suicide/self-harm (5) is a marginal case having the potential of becoming dependent. Still, since we have religiously followed the scale-centric approach of dividing the Cartesian plane into four quadrants and technically it falls in linkage quadrant, therefore, we reported as it is. The factors that have high driving but low dependence power are called independent. They can influence and drive the other factors and need immediate attention because they are critical to the system. In this study, outcome “employment instability” coded as (1) is an independent factor that needs the immediate attention of policymakers. The factors with low driving power but high dependence power are called dependent. They are least critical to the system; in this study, “suicide/self-harm” coded as (5), though technically fall in linkage, has the potential to become dependent and is least critical as such. It can be taken care of indirectly. The factors that have high dependence and driving power (at the same time) are known as linkage. They are unsure, very agile, and unsettled factors, and action on these factors affects others and in turn to themselves; therefore, taking any policy decision/action on them demands high care. If the majority of the outcomes fall under this quadrant, it means that the system is yet in the process of making some sense. The results that have low driving and low dependence are known as autonomous. They are independent of the system; therefore, they need to be removed, but sometimes they are also important, having few powerful connections. The absence of autonomous factors is considered as evidence of the fact that all factors under study are relevant to the system. There is no independent factor in this study that means that all factors under investigation are essential. Overall, this research study shows that employment instability is the crucial outcome that has a significant impact. The results are displayed and juxtaposed in Table 10.

Against all the outcomes, driving, dependence, effectiveness, quadrants, and level are mentioned to visualize the results in eye span. One of the factors is highlighted in grey and contains comments as “key factor.” It is the most critical outcome, as evident from the results of this study.

Discussion

With the main objectives of identifying, assessing, and analyzing the social outcomes of pandemics and applying ISM/MICMAC as methodologies, valuable results surfaced. It is worth discussing the study’s findings in reality and against contemporary literature. Among the influx of the published/unpublished literature, the study is distinct on many counts. Studying stressful behaviors is admittedly a crystalized topic, but studying it in the COVID-19 pandemic is a recent phenomenon. Fear, stress, short temperedness, fetter sound sleeps, suicidal ideation, insecurity, unemployment, frustration, boredom-ness, emotional instability, depression, etc. The variables like that are studied many times by many studies in traditional fashion. One can find hundreds of studies using large statistical samples of thousands of respondents and analyzing them through deterministic models. The social outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic are the aftermath of a very recent phenomenon that needs to be approached holistically and differently. We built a study that addresses the issue differently and instead compressively since it is envisaged on many variables, depth instead of breadth of a dataset, aggregate mental models of an expert focus group, different contextual and study settings, and new methodologies. We could not find literature that directly addresses this issue in a comprehensive exploratory manner. The survey unearthed and structured the poorly articulated complex relations of different social outcomes of the pandemic. The structural model that emerged from this study is a validated logical model coupled with a classification of variables that can hardly be found in the literature. Pinpointing one key variable (i.e., employment instability) based on empirical evidence makes this study distinct from within influx of literature. Following are the studies that we find a bit closer and can be contrasted to the current study (Table 11).

Bodrud-Doza et al. (2020) is a study based on online surveys using the principal component and hierarchical cluster analysis. It reveals a significant positive relationship between fear of COVID-19 pandemic and socio-economic crises. This study used an extensive set of statistical data. It provided a piece of limited information on the deterministic pattern, and it is different from the current research on accounts of methodology, data set, scope, context, and the results. Rossi et al. (2020) tested the anxiety-buffer hypothesis, a statistical study conducted in relatively a narrow scope and is different from the current research in-depth and scope. Cerami et al. (2020) theoretically evaluated the differences in the perceived impact of COVID-19 on society, economy, and health. This is undoubtedly a good attempt but did not provide any empirical evidence; therefore, the current study is also different because it is an empirical study based on real-time data collected from an affected focus group. Although these studies generally addressed the phenomenon like the current research, the present study is more comprehensive in scope, uses rigorous methodologies, and contributes relatively more accurate information on the phenomenon under investigation.

Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemic has created havoc for humanity, making everything unstable and uncertain. The lives of the people are disturbed. Most people feel loneliness, boredom, frustration, emotional instability, employment instability, and distress as fewer recreational and healthy activities are available. Screen time has increased, individual eating habits, and eating capacity have also increased, which leads to obesity which is also a source of stress. The study aims to assess and analyze the social outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Outcomes are identified from the literature, data concerning the paired relationships among outcomes are collected from experts, and ISM is used for modeling and MICMAC for analysis. There are sixteen significant outcomes found due to literature reviews considered for this research study. Results of ISM reveal that the outcomes coded as 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, and 12 falls on Level I, outcomes coded as 3, 6, 9, 10, 13, 14, and 15 fall at Level II, outcome coded as 16 falls at Level III, and outcome coded as 1 falls at Level IV. Results of MICMAC revealed that the outcome coded as 1 is categorized in the independent quadrant, and outcomes coded as 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16 are categorized in linkage quadrant, whereas, no outcome falls under autonomous and dependent quadrant; however, outcome coded as 5 is a marginal case having the potential of becoming dependent. Overall results of this research study show that “employment instability” is the critical social outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has a significant impact on society as an aftermath. The rest of the outcomes are driven by this one decisive, independent outcome.

Theoretical contributions

The study has contributed a list of outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic, ISM model, MICMAC (driving-dependence) diagram, and simplified information about inter-relationships and influences of those outcomes.

Practical implications of the study

This study is valuable for:

-

1.

Middle-class jobholders provide them with a lot of new information on possible outcomes.

-

2.

It is helpful for health officials and regulators as it embodies policy guidelines and directions to redress and redirect the social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

3.

Academia and researchers since it provides a refined theoretical framework for future research. The community at large allows for understanding and a lot of insights into the complex relations underlying among outcomes.

Limitations of the study and directions for future studies

There are certain study limitations. First, it uses a qualitative approach to address the issue; therefore, future studies should use quantitative methods to address the issue more objectively. Second, the data has been collected from respondents from Pakistani middle-income families; therefore, the study results are generalizable accordingly. In this context, future studies can be conducted in different countries. Third, a limited number of outcomes are investigated; therefore, future studies can add more results and replicate the study. Four, the data has been collected from a limited number of individuals; it is recommended that the data should be collected from more respondents from different backgrounds to corroborate the study results.

Data availability

Available upon request.

References

Abbass K, Begum H, Alam ASA, Awang AH, Abdelsalam MK, Egdair IMM, Wahid R (2022) Fresh Insight through a Keynesian Theory Approach to Investigate the Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Pakistan. Sustainability 14(3):1054.

Abbass K, Niazi AAK, Qazi TF, Basit A, Song H (2021b) The aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic period: barriers in implementation of social distancing at workplace. Library Hi Tech

Abbass K, Song H, Khan F, Begum H, Asif M (2021a) Fresh insight through the VAR approach to investigate the effects of fiscal policy on environmental pollution in Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res 1–14

Amit S, Barua L, Kafy AA (2021) A perception-based study to explore COVID-19 pandemic stress and its factors in Bangladesh. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev 6(7):e04399

Asarnow JR, Goldston DB, Tunno AM, Inscoe AB, Pynoos R (2020) Suicide, Self-Harm, & Traumatic Stress Exposure: A Trauma-Informed Approach to the Evaluation and Management of Suicide Risk. Evid-Based Pract Child Adolesc Mental Health 5(4):483–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1796547

Atif M, Malik I (2020) Why is Pakistan vulnerable to COVID-19 associated morbidity and mortality? A scoping review. Int J Health Plan Manag 35(5):1041–1054

Banerjee D, Rai M (2020) Social isolation in Covid-19: The impact of loneliness. Int J Soc Psychiatry 66(6):525–527

Bäuerle A, Teufel M, Musche V, Weismüller B, Kohler H, Hetkamp M...., Skoda EM (2020) Increased generalized anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Germany J Public Health 42(4): 672-678

Bodrud-Doza M, Shammi M, Bahlman L, Islam ARM, Rahman M (2020) Psychosocial and socio-economic crisis in Bangladesh due to COVID-19 pandemic: A perception-based assessment. Front Public Health 8:341

Burke T, Berry A, Taylor LK, Stafford O, Murphy E, Shevlin M.…, Carr A (2020) Increased Psychological Distress during COVID-19 and Quarantine in Ireland: A National Survey. J Clin Med 9(11): 3481

Caprara GV, Pastorelli C (1993) Early emotional instability, prosocial behaviour, and aggression: some methodological aspects. Eur J Pers 7(1):19–36

Cerami C, Santi GC, Galandra C, Dodich A, Cappa SF, Vecchi T, Crespi C (2020) Covid-19 outbreak in Italy: Are we ready for the psychosocial and the economic crisis? Baseline findings from the Psy Covid study. Front Psych 11:556

Chen IS (2020) Turning home boredom during the outbreak of COVID-19 into thriving at home and career self-management: The role of online leisure crafting. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 32(11):3645–3663

Di Mauro F, Syverson C (2020) The COVID crisis and productivity growth. VOX CEPR Policy Portal, 16.

Dietz W, Santos-Burgoa C (2020) Obesity and its implications for COVID-19 mortality. Obesity (Silver Spring) 28(6):1005

Egede LE, Ruggiero KJ, Frueh BC (2020) Ensuring mental health access for vulnerable populations in COVID era. J Psychiatr Res 129:147–148

Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ballard C, Christensen H, Silver RC, Everall I, Ford T (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7(6):547–560

Huang Y, Haseeb M, Usman M, Ozturk I (2022) Dynamic association between ICT, renewable energy, economic complexity and ecological footprint: Is there any difference between E-7 (developing) and G-7 (developed) countries? Technol Soc 68:101853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101853

Hussain A, Mahawar K, Xia Z, Yang W, EL-Hasani S (2020) Obesity and mortality of COVID-19. Meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract 14(4):295–300

Iob E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D (2020) Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the U.K. during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Psychiatry 217(4):543–546

Islam SDU, Bodrud-Doza M, Khan RM, Haque MA, Mamun MA (2020) Exploring COVID-19 stress and its factors in Bangladesh: A perception-based study. Heliyon 6(7):e04399

Jena J, Sidharth S, Thakur LS, Pathak DK, Pandey VC (2017) Total interpretive structural modeling (T.I.S.M.): Approach and application. J Adv Manag Res 14(2):162–181

Kesar S, Abraham R, Lahoti R, Nath P, Basole A (2021) Pandemic, informality, and vulnerability: Impact of COVID-19 on livelihoods in India. Can J Dev Stud/Revue canadienne d'études du développement 42(1-2): 145-164

Khan S, Khan M, Maqsood K, Hussain T, Noor-ul-Huda, Zeeshan M (2020) Is Pakistan prepared for the COVID-19 epidemic? A questionnaire-based survey. J Med Virol 92(7):824–832

Killgore WD, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Dailey NS (2020) Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res 290:113117

Krishnakumar B, Rana S (2020) COVID 19 in I.N.D.I.A.: Strategies to combat from combination threat of life and livelihood. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 53(3):389–391

Lee J, Lim H, Allen J, Choi G (2021) Multiple Mediating Effects of Conflicts With Parents and Self-Esteem on the Relationship Between Economic Status and Depression Among Middle School Students Since COVID-19. Front Psychol 12:3128

Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH, Zhao YJ, Zhang Q, Zhang L...., Xiang YT (2020) Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci 16(10): 1732

Mamun MA, Ullah I (2020) COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty? The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain Behav Immun 87:163–166

McGuine TA, Biese KM, Petrovska L, Hetzel SJ, Reardon C, Kliethermes S...., Watson AM (2021) Mental health, physical activity, and quality of life of U.S. adolescent athletes during COVID-19-related school closures and sport cancellations: A study of 13,000 athletes. J Athl Train 56(1): 11–19

Niazi AAK, Qazi TF, Basit A (2019a) An Interpretive Structural Model of Barriers in Implementing Corporate Governance (CG) in Pakistan. Global Reg Rev 4(1):359–375

Niazi AAK, Qazi TF, Basit A, Khan KS (2019b) Curing Expensive Mistakes: Applying I.S.M. on Employees’ Emotional Behaviors in Environment of Mergers. Rev Econ Dev Stud 5(1):79–94

Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S (2020) Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 323(18):1775–1776

Paul A, Nath TK, Mahanta J, Sultana NN, Kayes ASMI, Noon SJ.…, Paul S (2021) Psychological and Livelihood Impacts of COVID-19 on Bangladeshi Lower Income People. Asia-Pacific J Public Health 33(1): 100-108

Peters MDJ, Bennett M (2020) The mental health impact of COVID-19. Aust J Adv Nurs 37(4):1–3

Qazi TF, Niazi AAK, Hameed R, Basit A (2020) How they get stuck? Issues of women entrepreneurs: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Paradigms 14(1):73–79

Rana W, Mukhtar S, Mukhtar S (2020) Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatry 51:102080

Rossi A, Panzeri A, Pietrabissa G, Manzoni GM, Castelnuovo G, Mannarini S (2020) The anxiety-buffer hypothesis in the time of COVID-19: When self-esteem protects from the impact of loneliness and fear on anxiety and depression. Front Psychol 11:2177

Saqlain M, Munir MM, Ahmed A, Tahir AH, Kamran S (2020) “Is Pakistan prepared to tackle the coronavirus epidemic”? Drugs Ther Perspect 36(5):213–214

Shaukat MZ, Niazi AAK, Qazi TF, Basit A (2021) Analyzing the underlying structure of online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic period: An empirical investigation of issues of students. Front Psychol 12:1126

Stickley A, Matsubayashi T, Ueda M (2021) Loneliness and COVID-19 preventive behaviours among Japanese adults. J Public Health 43(1):53–60

Szabo TG, Richling S, Embry DD, Biglan A, Wilson KG (2020) From Helpless to Hero: Promoting Values-Based Behavior and Positive Family Interaction in the Midst of COVID-19. Behav Anal Pract 13(3):568–576

Szwarcwald CL, Malta DC, Barros MBDA, de Souza Júnior PRB, Romero D, de Almeida WDS.... abd de Pina MDF (2021) Associations of Sociodemographic Factors and Health Behaviors with the Emotional Wellbeing of Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(11): 6160

Usman M, Balsalobre-Lorente D (2022) Environmental concern in the era of industrialization: Can financial development, renewable energy and natural resources alleviate some load? Energy Policy 162:112780

Usman M, Balsalobre-Lorente D, Jahanger A, Ahmad P (2022) Pollution concern during globalization mode in financially resource-rich countries: Do financial development, natural resources, and renewable energy consumption matter? Renew Energy 183:90–102

Usman M, Khalid K, Mehdi MA (2021) What determines environmental deficit in Asia? Embossing the role of renewable and non-renewable energy utilization. Renew Energy 168:1165–1176

Venter ZS, Barton DN, Gundersen V, Figari H, Nowell M (2020) Urban nature in a time of crisis: Recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ Res Lett 15(10):104075

Wang C, Tee M, Roy AE, Fardin MA, Srichokchatchawan W, Habib HA...., Kuruchittham V (2021) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: A study of seven middle-income countries in Asia. Plos One 16(2): e0246824

Warfield JN (1973) Binary matrices in system modeling. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern (5): 441–449

Warfield JN (1974) Toward interpretation of complex structural models. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern (5):405–417

Waris A, Atta UK, Ali M, Asmat A, Baset A (2020) COVID-19 outbreak: Current scenario of Pakistan. New Microbes New Infect 35(20):100681

Williams K, Frech A, Carlson DL (2010) Marital status and mental health. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. p 306–320

Williams SN, Armitage CJ, Tampe T, Dienes K (2020) “Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK-based focus group study. BMJ Open 10(7):e039334

Wilson JM, Lee J, Fitzgerald HN, Oosterhoff B, Sevi B, Shook NJ (2020) Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J Occup Environ Med 62(9):686–691

Yang B, Usman M (2021) Do industrialization, economic growth and globalization processes influence the ecological footprint and healthcare expenditures? Fresh insights based on the STIRPAT model for countries with the highest healthcare expenditures. Sustain Prod Consum 28:893–910.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The idea of the original draft belongs to Kashif Abbass and Dr. Abdul Aziz Khan. Dr. Abdul Basit writes the introduction, literature review, and empirical outcomes sections. Dr. Ramish Mufti, Dr. Nauman Zahid, and Dr. Tehmina Fiaz Qazi helped collect and visualize data of observed variables. Dr.Kashif Abbass and Dr.Abdul Aziz Khan Niazi constructed the methodology section in the study. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirmed that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal. Ethical approval and informed consent are not applicable for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Philippe Garrigues

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abbass, K., Basit, A., Niazi, A.A.K. et al. Evaluating the social outcomes of COVID-19 pandemic: empirical evidence from Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30, 61466–61478 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19628-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19628-7